Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Memorial Service in Critical Care

Загружено:

Andra AndraАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Memorial Service in Critical Care

Загружено:

Andra AndraАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

PRACTICE DEVELOPMENT

The planning, organising and delivery of a memorial service in critical care

Jane Platt

SUMMARY The Intensive Care Society (1998) recommends that facilities should be available to follow up bereaved relatives As part of bereavement follow up, a memorial service has been held at Royal Preston Hospital for the last three years. Over 300 people attended in 2003 A memorial service is often referred to as a ritual. Rituals seem to meet certain universal needs, such as confirming the reality of the death, assisting in the expression of feelings, stimulating memories of the deceased and providing support to the family and friends of the deceased An audit in 2003 has confirmed the value of the service: 97% of attendees were glad they attended the service and 72% would like to be invited to the service again next year

Key words: Bereavement support Critical care Death and dying Follow up service Memorial service Rituals

INTRODUCTION

In a study of 26 intensive care units (ICUs) in the United Kingdom, the average intensive care mortality rate was 18% (Rowan et al., 1993). In most cases, relatives or friends will have been involved with the dying patient on the critical care unit (CRCU). Over the last two decades, health care professionals have been showing an increasing interest in issues related to death, dying and care of the bereaved (Jackson, 1998). The Intensive Care Society (1998) recommends that facilities be available to follow up bereaved relatives. Follow up of bereaved relatives often involves letters (Jackson, 1998) or phone calls (Wilson et al., 2000). At the Royal Preston Hospital, the follow up of bereaved relatives in the CRCU has incorporated a memorial service. The unit has organised a memorial service for the last 3 years, and in 2003, an audit was carried out a month after the service. The purpose of the audit was to ensure that the needs of those who attended the service were being met and thereby to evaluate the service.

THE VALUE OF A MEMORIAL SERVICE IN CRITICAL CARE

A literature review using MEDLINE (19842004) was undertaken to find examples of memorial services in health care settings. One study suggested that over 645% of hospices offer memorial services to bereaved family members (Lattanzi-Licht, 1989). The search revealed evidence of a memorial service on a renal unit (Ormandy, 1998), in a nursing home in Florida (Urbancek, 1994), for HIV health care workers in New York (Tiamson et al., 1998), and for palliative care patients in a hospital setting (Rawlings and Glynn, 2002), amongst others. However, no evidence could be found in the literature for a memorial service in critical care. This supports Granger and Shellys (1997) statement that most of the public work on bereavement deal with the consequences of anticipated death from chronic or malignant disease, rather than the effects of sudden bereavement in an unfamiliar environment. At Preston, we were unsure as to what response we would get to the memorial service as there was no supporting literature to guide us. Sudden and unexpected deaths are an integral part of critical care. Parkes (1975) identified that in sudden death, there was clearly a more emotionally disturbed response which persisted throughout the first year of bereavement. Despite often having only short-term contact with patients and family members, critical care nurses responses to relatives bereavement are

Names of the deceased have been changed to preserve anonymity. Author: J Platt, RGN, ENB100, BA (Hons), Senior Sister, Critical Care Unit, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Royal Preston Hospital, Sharoe Green Lane, Fulwood, Preston PR2 9HT Address for correspondence: Critical Care Unit, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Royal Preston Hospital, Sharoe Green Lane, Fulwood, Preston PR2 9HT E-mail: jane.platt@lthtr.nhs.uk

222

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

Memorial service in critical care

important and may have longer term implications (Sanders, 1989). Previous research has shown that if nursing staff ensure the delivery of humanistic care and make every effort to be sensitive to bereaved relatives needs in the ICU, it will do much to ease their stress during a traumatic time (Hampe, 1975; Breu and Dracup, 1978). At Preston, the memorial service has become an integral part of the delivery of humanistic and sensitive care. A memorial service is a significant intervention in bereavement support, which provides an opportunity for the staff to be available for closure (Foulstone et al., 1993). A memorial service is often referred to as a ritual, similar to a funeral. Rituals seem to meet certain human universal needs, such as confirming the reality of the death, assisting in the expression of feelings, stimulating memories of the deceased and providing support to the family and friends of the deceased (Rando, 1984). Our experience at Preston supports the importance of a memorial service as an important ritual following death in the CRCU.

PLANNING OF THE MEMORIAL SERVICE

There has been a bereavement group on the unit for 14 years. Part of the role of this group has been to write to the family or friends of those bereaved approximately 6 weeks after the death. The purpose of this letter was to let them know they are still in our thoughts and to invite them to telephone if there is anything else we could help them with. Some relatives have wanted an appointment with a doctor and/or nurse to review what happened to their relative while on the CRCU, others have asked for contact telephone numbers for local support groups such as Cruse or Compassionate Friends. There has been a lot of positive feedback from the letters. Many staff received personal replies of thanks in response to the letters. However, a study by Jackson (1998) evaluating follow up letters to bereaved families found that while 34% believed the letter gave them permission to call the ICU to ask questions if desired, 25% believed the nurses to be too busy. In reality, very few relatives call the unit at Preston as a direct result of the letter, possibly because of this very reason. Other local units, such as the coronary care unit at Blackpool, telephone relatives as part of a bereavement support programme (Wilson et al., 2000). It was believed that this would be extremely difficult to achieve on our unit as it has a very large throughput and the annual death rate is around 150. At a bereavement group meeting held in the autumn of the year 2000, it was suggested that a memorial service could be a beneficial way of provid-

ing an additional form of follow up. The meeting was led by myself and included six nursing staff who had expressed a particular interest in bereavement. We were aware that there was already an annual service organised by the special care baby unit, and one held for the carers of deceased patients from the renal unit at Preston. The hospital chaplain, who had led the service from the renal unit, was contacted. A meeting was arranged between the hospital chaplain, the manager on the unit and nurses who had expressed an interest in assisting with the organisation of a service. The unit manager supported the service and agreed to provide protected time for me to organise it and write the invitations. A full working day is now allocated every year for writing invitations to carers, and up to two meetings are held with the pastoral care department and catering staff. Funding is provided by the unit for tea and coffee after the service and all other expenses such as flowers, candles invitations and postage. At the 2003 service, the invitations, envelopes and order of service were all provided free by the printing company used by the hospital. Also, the estates department had agreed to waive the car park fee for all those who attended the service. These examples of professional and organisational collaboration are much appreciated.

MOVING FORWARD

Members of bereavement group discussed the best way of raising awareness about the service. One suggestion of an advert in the local newspaper was dismissed as the unit has a large catchment area across the whole of the North-west of England. We considered setting the date for the service well in advance and informing relatives of the date in the letter of support sent to them 6 weeks after the death of the patient. However, we felt that weeks or months later, the date might be mislaid. It was therefore decided that a better approach would be to send out invitations, a month before the service, to all those bereaved in the past year. Deciding when to hold the service was also an issue. Many bereaved relatives returning to the unit have said how difficult and emotional Christmas was for them, especially in the first year after their bereavement. Holding the service in December was considered, but it was felt that December is often a busy and potentially stressful time for some nursing staff due to Christmas preparations. Also, as not everyone in a multicultural society believes in or celebrates this occasion, any emphasis on Christmas during the service would be inappropriate for some. It was eventually decided to hold the service at the beginning of February This would mean that the invitations would

223

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

Memorial service in critical care

be posted in the first week of January and would perhaps be viewed by some as welcome support after the emotions at Christmas. Invitations were sent to the next of kin and/or friends and family of those bereaved between January 1 2000 and January 1 2001. We recognised that the timing of the service would be more appropriate for some rather than others, but that this would be reviewed and evaluated after the service. The service was held in the hospital chapel, although it was emphasised that it would be a nondenominational service.

Table1 Numbers of participants at the 2003 memorial service Type of participant Bereaved relatives or friends Nursing staff Medical staff Pastoral care staff Number 320 9 1 4

ORGANISING THE MEMORIAL SERVICES

180 people attended the first memorial service. A candle lighting ceremony was held as part of the service. A Book of Remembrance was also provided, which was left in the chapel after the service. Families and friends stayed for tea and coffee, talked to members of staff and wrote in the Book of Remembrance. Many of these past carers stayed for up to an hour and a half after the service. This response, which seemed overwhelming, was a clear indication to us of the value of the service. We received a lot of verbal encouragement and thanks on the day of the service, and several families wrote afterwards to explain what the service had meant to them. The bereavement group therefore decided to make the service an annual event. During the year following the first service, each newly bereaved family continued to receive a letter from the bereavement group 6 weeks after the death of the patient. The letter was extended to include information regarding the memorial service scheduled for February 2002 and stated that a Book of Remembrance was available. In January 2002, the bereavement group sent invitations to all the families bereaved over the previous 12 months. Again the response was overwhelming, so much so that 2 days before the service, it became apparent that the chapel could not hold the numbers of expected people. A decision was taken to change the venue to the hospital restaurant, opposite the chapel. On the day of the service, 300 people attended. Again, many stayed for a long time after the service, talking to staff, lighting a candle in the chapel and writing in the Book of Remembrance. In the light of this experience, the 2003 service was also planned to take place in the restaurant. One disadvantage of the restaurant is that the candle lighting ceremony cannot take place, due to the presence of smoke alarms. The candle lighting ceremony had proved to be a very emotional part of the original service in the chapel, and we wanted to include some224

thing similar in the 2003 service; hence we decided to introduce a flower ceremony. Each family was given a white carnation on arrival, and as part of the service, they were invited to present the flower at the front of the restaurant in a ceremony of reflection and remembrance. Everyone was also invited to light a candle in the hospital chapel after the memorial service. In total, over 320 people attended the February 2003 service. Nine members of the nursing staff attended, six read out a piece of poetry or prose. One consultant from the unit attended, as well as four members of the pastoral care department (Table 1). The service was led by the Head of Pastoral Care, John Prysor-Jones. Table 2 summarises details of how many invitations were sent for each month in 2002. Six relatives who had been bereaved prior to 2002 had also expressed a desire to attend the service. A total of 159 invitations were sent. Of those 159, 52 families replied to say they would like to attend. Each family was asked to give an indication of how many people would be attending. The final column of Table 2 gives the number of people expected from the replies received. In total, we were expecting 258 people to attend, based on the number of replies received. However, on the day, the number of attendees was around 320. Clearly, some

Table2 Details of numbers of invitations and replies Timing of deaths (2002) January February March April May June July August September October November December Pre-2002 deaths Total Number of replies 2 3 4 6 3 5 3 4 3 5 4 5 5 52 Number expected to attend 9 12 14 27 9 43 12 22 18 34 17 28 13 258

Number sent 16 12 13 13 13 9 7 13 13 15 9 20 6 159

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

Memorial service in critical care

people had attended without replying, and some families had brought more people on the day than they had originally indicated. Some families had telephoned the unit to ask whether extra people could be brought, but we had to limit the total numbers. More than 350 would have presented a fire risk, and we also had to allow for the members of staff who would be attending, as well as people who turned up on the day without replying to the invitation.

AUDIT OF THE MEMORIAL SERVICE

It was decided that whilst we had had a lot of informal positive feedback from attendees of the memorial services (Appendix 1), it would be informative to carry out a formal audit to evaluate the February 2003 service. The audit was undertaken by distributing a questionnaire to those who had accepted the invitation to attend the service. Those who had not replied, but then turned up on the day of the service, were not included. A total of 52 questionnaires were distributed, 33 were returned (compliance rate 635%).

an aspect of the service, and the responses given in all questions except question five were Yes, No or Dont Know. In question five, respondents were asked to tick either More formal or Less formal. Respondents were also invited to write comments following each question. Ethical approval is not normally required for audit purposes. However, as an act of courtesy, the ethics committee were made aware of the audit by letter. The chairman replied that he was satisfied that the questionnaire represented audit and therefore did not need to come before the ethics committee. To ensure anonymity:

no personal details or details regarding the

deceased were requested from respondents

all questionnaires were returned to the Depart

ment of Clinical Governance and Audit, who supplied prepaid return envelopes. the data were analysed by staff of the Department of Clinical Governance and Audit who then forwarded a report to the CRCU

Audit methodology

Audit questions were adapted from a questionnaire used in an evaluation of a palliative care memorial service in Australia (Foulstone et al., 1993). Several staff who had attended the service were asked to comment on the questionnaire; these included six nurses, the unit manager and the Head of the Pastoral Care Department. Advice was sought from the Department of Clinical Governance and Audit within the hospital, and minor changes were made to the first draft as a result of comments received. The full list of questions can be found in Appendix 2. Each question addressed

100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30

52% n = 17 97% n = 32 94% n = 31 82% n = 27 61% n = 20

FINDINGS

Figure 1 details the numbers who gave positive (i.e. approving) responses to each question and also gives this data as percentages of the total number of respondents. Examples of the comments added by respondents are included in the following discussion.

Venue

Memorial services are reported in the media regularly, particularly, after a tragic incident, and they are frequently held in a church or cathedral. We worried that there would be an expectation that the service,

100% n = 33

94% n = 31

97% n = 32 72% n = 24

55% n = 18

55% n = 18

20 10 0 Venue suitable Poetry/prose helpful Right religious input Involvement of staff adequate Formality of service right Happy with no singing Happy not to Like sitting contribute round a table Flower ceremony appropriate Glad attended Like to be re-invited

Figure1 Percentages of positive responses 2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

225

Memorial service in critical care

although essentially non-religious, should be held in the chapel. However, all but one (97%, n =32) thought that the hospital restaurant was a suitable venue. One person (3%) did not indicate a reply. It is reassuring to have such a positive response to the venue. Comments included: comfortable and pleasant, very informal but nice and it was very peaceful and appropriate for families. The reasons for not holding the service in the chapel were clearly explained as part of the introduction to the service. Perhaps, the fact that the service was not being held in the chapel encouraged some nonreligious and different faith families to attend. One of the few criticisms of the service was that we needed better audio as we could hardly hear. Indeed, there was a problem with one of the speakers in the restaurant on the day of the service which only occurred after the service started, and which we were unable to resolve on the day. It may be necessary in the future to hire equipment from an outside source.

unfair and opening prayers and at the end would be nice. So far, we have not included religious content. Our priority has been to include content that would be acceptable to a variety of religious faiths, or those with no religious faith. We now acknowledge that some religious content may be appropriate, as a small part of the service in the future. However, we must take care to remember that the majority did not want more religious input as they thought it was just right.

Staff involvement

A total of 82% (n =27) stated that the involvement by the staff was adequate, 9% (n =3) said the level was not adequate, 6% (n =2) did not know and one respondent (3%) did not indicate a reply. Given the fact that the unit had to be adequately staffed, and the fact that staff attended in their own time at a weekend, we considered the attendance was excellent, i.e. nine nursing staff as summarised in Table 1. Six members of the nursing staff also read out part of the Order of Service. On the day of the service, many relatives commented on how grateful they were for the staff involvement and their willingness to participate in the service itself. This gratitude is reflected in the comments given: the involvement of the busy nurses amazed me, they were wonderful, the staff have my full admiration, the staff did a wonderful job, they were so caring and dedicated and staff involvement greatly appreciated. Interestingly, one person commented that they didnt see many doctors. Frequent rotation of junior doctors meant that they were unlikely to know many of the families and therefore unlikely to wish to attend. However, one consultant attended. Two other consultants were very supportive of the service, but could not attend due to other commitments. In the last 3 years, several families have been able to talk to a Consultant at the service. They have found this to be a very important part of their grieving and healing process. Continuous multiprofessional working with the medical staff may increase their presence at future services.

Reading of poetry/prose

In total, 94% (n =31) felt that the reading of poetry/ prose was helpful to them, one respondent (3%) indicated it was not helpful and one (3%) responded with dont know. Two of the poems used in the service had been written by relatives who had lost a family member on our unit. The remainder of the readings were chosen from a variety of sources, with great care taken not to introduce too much of a religious theme. Each year, we vary the choice of readings or poems and try to get a mixture of some that identify with the pain of bereavement, and some that try to look towards the future with hope. We have used one poem at every service, because we have had so many positive comments about how appropriate it is in that setting (this poem is included in Appendix 3). All the readings and poems are printed in the Order of Service which families can take away with them to read again at home. In 2003, we printed 300 copies of the Order of Service, which proved to be more than enough. The audit reflects that we seem to have achieved the right balance for the majority. This is supported by positive comments such as: very moving and meaningful, very touching, helpful and emotional and it was very appropriate as we could associate with other peoples feelings'.

Formality of service

An encouraging 61% (n =20) felt that the formality of the service was just right, 12% (n =4) would have preferred it to be more formal, although no comments were given as to how it should be made more formal. Only 9% (n =3) would have preferred it to be less formal, one respondent (3%) replied dont know and 15% (n =5) did not indicate a reply. Comments given included: the format was just perfect and I think the formality of the occasion was about right. If we were to change the format to suit the minority, we would risk upsetting the majority. Given the numbers of people involved, it would be impossible for it to be just right

Religious input

Only 36% (n =12) would have liked more religious input, 52% (n =17) did not want more religious input and 12% (n =4) did not know. Respondents understood the difficulties that including religious content could pose with so many different faiths involved: I am a Catholic, but so many different faiths it would be

226

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

Memorial service in critical care

for everyone. We believe that as a result of the audit, it would not be wise to change the formality of the service in any significant way.

Seating arrangements

It is totally reassuring that 100% (n =33) liked sitting around a table. After holding the first service in the chapel, where families were sitting in rows, it was a concern to us the following year that they would be sitting around a table in the restaurant. There was particular concern that some would be forced to share a table with strangers at a time when they would possibly have preferred not to talk to others. In the previous year, one family who had lost their elderly father, sat at a table with a young woman, whose husband had suddenly died of pneumonia when she was heavily pregnant with their second child. After the ceremony, the first couple had remarked that they found it quite traumatic to be sitting with a woman experiencing such great tragedy. There was concern that we were thrusting people together. Some people may have felt, and wished to be, more detached sitting in a row rather than around a table. Yet, the audit result has reassured us that this arrangement is appropriate.

Preference for singing

Compared to the enthusiastic response for poetry/ prose, only 33% (n =11) would have preferred there be some singing, 55% (n =18) did not want singing and 12% (n =4) replied dont know. This is something we may consider when planning for the next service, although finding the right song could prove difficult, given that only one-third of respondents wanted any singing at all. This is acknowledged with the comment: because of different views it would be hard to pick a song with the right words. The staff on the unit were intrigued by the comment that perhaps singing could be done by the staff. If there was a member of staff gifted in that field, it could perhaps add some poignancy to the service. However, at present, no one has admitted to such talents, and we should perhaps take comfort from the fact that the majority did not believe that there should have been some singing.

Flower ceremony

In total, 94% (n =31) felt the flower ceremony was appropriate, one respondent (3%) did not think it was appropriate and one more (3%) did not indicate a reply. The comments given about the flower ceremony were very positive: very simple, very thoughtful, a lovely touch, we said goodbye to our loved ones with the flowers, I felt this was one of the most moving parts of the service. Even the person who stated that the flower ceremony was inappropriate gave a positive written response: would have liked to take the flower home to press. It is difficult to know how we could achieve this, as each person presented the flower at the front of the restaurant as part of a moment of remembrance, and therefore would not be able to identify their own flower afterwards. All the flowers were taken into the chapel after the service and left on the altar in vases. Perhaps, we could ensure that some extra flowers are available for those who would like to take one home. The flower ceremony proved to be emotional and symbolic for many, and an appropriate replacement for the candle lighting ceremony. As something totally new in 2003, we were encouraged by the positive comments given in the audit.

Contribution to the service by relatives

The recent policy statement Comprehensive Critical Care asserts that partnership between professionals and patients should form the basis of critical care provision (Department of Health, 2000). However, in the present survey, only 18% (n =6) would have wished to contribute ideas regarding contents of the service and 55% (n =18) did not wish to contribute ideas. One of the respondents who did not wish to contribute stated the nurses can only do so much, and they should decide how much. Twenty-four per cent (n =8) did not know whether they wished to contribute, and one respondent (3%) did not indicate a reply. So far, relatives who have sent poems/prose to the unit have been contacted to gain permission to use them at the service. One such relative commented: one of my poems to my son Anthony was read out, I was very proud. Members of the nursing staff on the unit have chosen poems or prose that they feel to be the most appropriate, from a variety of sources. Since the audit, we have discussed this issue and wondered whether it should be mentioned when the support letter is dispatched 6 weeks following the bereavement. However, the concern would be that we would perhaps be inundated with requests, and it would be difficult to choose one over another. So far, at least one person per year has chosen to send to the unit a piece of poetry or prose that they have written themselves following their bereavement. We have then contacted these people prior to the service to ask permission to use their contributions at the service.

Were relatives glad they attended?

In total, 97% (n =32) said they were glad they attended the service. One respondent (3%) was not glad they attended but gave no reason for this response. The overall positive response to this question is particularly rewarding and was reinforced by many positive comments: I am still in awe of the depth of caring by the nurses, it brought my son closer and made me realise other

227

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

Memorial service in critical care

people are suffering like us, it helps to share the grief of others, I wouldnt have missed it, it gave us peace, and it closed a door for me and I was able to view the hospital that I wont ever have to come back to. This suggests that whatever minor changes respondents felt could be made, the service as a whole had proved to be a positive experience. However, it must be remembered that of those who did not return questionnaires, some may have chosen not to due to a negative experience.

relatives to return each year and try to identify reasons why many families chose not to attend the service at all. Perhaps, it is appropriate to conclude with a plea from one of the respondents in the audit: Please carry on this service, it is a great comfort to know people care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks everyone who has helped in any way with the organisation of the memorial services. In particular, the author thanks her managers Gill Nixon and Lindsay Bury; John Prysor-Jones (Head of Pastoral Care) and Sarah Haslam and Susan Baxter from the Clinical Governance and Audit Department. The author also thanks all the bereaved families who took the time to complete the questionnaires.

A desire for annual invitations?

Seventy-two per cent (n =24) would like to be invited to the service again next year, while 22% (n =7) did not wish to be invited again, one (3%) replied dont know and one (3%) did not indicate a reply. This indicates a positive feeling towards the service as reflected in the comments: I was very comforted, it provides a special time for remembrance and it is another link with Mary. Even the comments from the respondents who did not wish to attend again were positive: let someone else have a chance, we turned down such a lot of relations of Malcolm because of the numbers being limited, thank you again. This question does raise the issue of should relatives be invited each year. To do so would require finding a venue suitable to hold increasing numbers, or, alternatively, holding more than one service each year. This would increase the time spent in organisation, and also increase costs. However, as time goes on, many may believe that they no longer wish to attend again. It is something which would need careful consideration in the future.

REFERENCES

Breu C, Dracup K. (1978). Helping the spouses of critically ill patients. The American Journal of Nursing; 78: 5153. Dawes M, Davies P, Gray A, Mant J, Seers K, Snowball R. (1999). Evidence-Based Practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Department of Health. (2000). Comprehensive Critical Care. London: Department of Health. Foulstone S, Harvey B, Wright J, Jay M, Owen F, Cole R. (1993). Bereavement support: evaluation of a palliative care memorial service. Palliative Medicine; 7: 307311. Granger C, Shelly MP. (1997). Bereavement in the ICU. British Journal of Intensive Care; March/April: 5557. Hampe SO. (1975). Needs of the grieving spouse in a hospital setting. Nursing Research; 24: 13120. Intensive Care Society. (1998). Guidelines for Bereavement Care in Intensive Care Units. London: The Intensive Care Society. Jackson I. (1998). A study of bereavement in an intensive therapy unit. Nursing in Critical Care; 3: 141150. Lattanzi-Licht M. (1989). Bereavement services: practice and problems. Hospice Journal; 5: 128. Ormandy P. (1998). A memorial service for renal patients. EDTNA/ERCA Journal; 14: 2224. Parkes CM. (1975). Bereavement Studies of Grief in Adult Life, 2nd edn. London: Penguin. Rando T. (1984). Therapeutic interventions with grievers. In: Champaign IL, (ed.), Grief, Dying, and Death: Clinical Interventions for Caregivers. New York: Research Press. Rawlings D, Glynn T. (2002). The development of a palliative care-led memorial service in an acute hospital setting. International Journal of Palliative Nursing; 8: 4047. Rowan KM, Kerr JH, Major E, McPherson K, Short A, Vessey MP. (1993). Intensive care society's APACHE II study in Britain and Ireland-II. Outcome comparisons of intensive care units after adjustment for case mix by the American APACHE II method. British Medical Journal; 307: 977981. Sanders CM. (1989). Grief the Mourning After. New York: Wiley. Tiamson M, McArdle R, Girolamer T, Horowitz H. (1998). The institutional memorial service: a strategy to prevent burnout in HIV healthcare workers. General Hospital Psychiatry; 20: 124126. Urbancek A. (1994). Have you ever thought of a memorial service? Geriatric Nursing; 15: 100101. Wilson A, Norbury E, Richardson K. (2000). Caring for broken hearts patients and relatives: three years of bereavement support in CCU. Nursing in Critical Care; 5: 288293.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of audit was to find out am I doing the right thing, to the right people, at the right time? (Dawes et al., 1999). In carrying out our audit, we were seeking to evaluate the effectiveness of our service and to further reinforce a need to continue with it each year. The evidence gained from the audit supports the need to continue with the service as an annual event, and that currently only minor changes need to be made in the planning, organisation and delivery of the service. Looking back over the last 3 years, we have learned a lot and do feel we are doing the right thing, to the right people, at the right time. Although we still have much more to learn, we feel we could help others who wish to start up their own service, and we are also keen to share ideas with any other units who may already be holding memorial services. We hope to act as a resource and to try and encourage the development of memorial services as an integral part of bereavement follow up. For the future, we plan to continue to develop and improve the service. We need to assess the need for

228

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

Memorial service in critical care

APPENDIX 1

Letter of thanks from a relative who attended the service in 2003

On behalf of all my family, may I thank yourself, all your staff and everyone who helped make Sunday such a special day. A lot of thought and hard work went into the occasion. It was very moving, but also a lovely afternoon. It helps to see other people who you know have gone through the same experience as ourselves. I realise we are not alone. Other people are grieving as well. Once more, although the word is very inadequate thank you all.

APPENDIX 3

Death is nothing at all

Death is nothing at all I have only slipped away into the next room. I am I and you are you. Whatever we were to each other that we are still. Call me by my old familiar name, Speak to me in the easy way which you always used. Put no difference in your tone, Wear no forced air of solemnity or sorrow. Laugh as we always laughed At the little jokes we enjoyed together. Play, smile, think of me, pray for me. Let my name be ever the household word that it always was. Let it be spoken without effort, Without the ghost of a shadow on it. Life means all that it ever meant. It is the same as it ever was, There is absolutely unbroken continuity. Why should I be out of mind because I am out of sight? I am waiting for you for an interval, Somewhere very near, Just around the corner. All is well. (Canon Henry Scott Holland. St. Paul's Cathedral 18471918)

APPENDIX 2

Audit questions

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Was Charters Restaurant a suitable venue for you? How did you feel about the reading of poetry/prose? Was it helpful to you in this setting? Would you have liked the service to have more religious input? Was the level of involvement by staff adequate in your opinion? Would you have liked the service to be more or less informal? Would you have preferred there to be some singing? If you had been given the opportunity, would you have wished to contribute ideas about songs, poetry, or any part of the service? Did you like sitting around a table? Did you think the flower ceremony was appropriate? Were you glad you attended the service? Would you like to be invited again next year?

2004 British Association of Critical Care Nurses, Nursing in Critical Care 2004 Vol 9 No 5

229

Вам также может понравиться

- Memorial Service For Families of Children Dying From Cancer or Hematologic DisordersДокумент9 страницMemorial Service For Families of Children Dying From Cancer or Hematologic DisordersAndra AndraОценок пока нет

- Survey of UK Hospices and Palliative Care Adult Bereavement ServicesДокумент9 страницSurvey of UK Hospices and Palliative Care Adult Bereavement ServicesAndra AndraОценок пока нет

- Durham Psych InternДокумент14 страницDurham Psych InternAndra AndraОценок пока нет

- CollegeДокумент4 страницыCollegeAndra AndraОценок пока нет

- Facultate McollegeanagerДокумент7 страницFacultate McollegeanagerAndra AndraОценок пока нет

- Grief Support For Caregivers of Palliative Care Patients in SpainДокумент12 страницGrief Support For Caregivers of Palliative Care Patients in SpainAndra AndraОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- The Future Mixed TensesДокумент4 страницыThe Future Mixed TensesChernykh Vitaliy100% (1)

- Second Language Learning in The Classroom PDFДокумент2 страницыSecond Language Learning in The Classroom PDFThanh Phương VõОценок пока нет

- Visvesvaraya Technological University: Jnana Sangama, Belgavi-590018, Karnataka, INDIAДокумент7 страницVisvesvaraya Technological University: Jnana Sangama, Belgavi-590018, Karnataka, INDIAShashi KaranОценок пока нет

- M 995Документ43 страницыM 995Hossam AliОценок пока нет

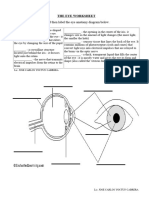

- The Eye WorksheetДокумент3 страницыThe Eye WorksheetCally ChewОценок пока нет

- Guide For Sustainable Design of NEOM CityДокумент76 страницGuide For Sustainable Design of NEOM Cityxiaowei tuОценок пока нет

- Good Manufacturing Practices in Postharvest and Minimal Processing of Fruits and VegetablesДокумент40 страницGood Manufacturing Practices in Postharvest and Minimal Processing of Fruits and Vegetablesmaya janiОценок пока нет

- LANY Lyrics: "Thru These Tears" LyricsДокумент2 страницыLANY Lyrics: "Thru These Tears" LyricsAnneОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Architecture Is The Architecture of The 21st Century. No Single Style Is DominantДокумент2 страницыContemporary Architecture Is The Architecture of The 21st Century. No Single Style Is DominantShubham DuaОценок пока нет

- Dadm Assesment #2: Akshat BansalДокумент24 страницыDadm Assesment #2: Akshat BansalAkshatОценок пока нет

- Character Paragraph Analysis RubricДокумент2 страницыCharacter Paragraph Analysis RubricDiana PerrottaОценок пока нет

- Notes 3 Mineral Dressing Notes by Prof. SBS Tekam PDFДокумент3 страницыNotes 3 Mineral Dressing Notes by Prof. SBS Tekam PDFNikhil SinghОценок пока нет

- Chapter 4 PDFДокумент26 страницChapter 4 PDFMeloy ApiladoОценок пока нет

- HP 6940 Manual CompleteДокумент150 страницHP 6940 Manual CompletepaglafouОценок пока нет

- A Review On PRT in IndiaДокумент21 страницаA Review On PRT in IndiaChalavadi VasavadattaОценок пока нет

- PresentationДокумент6 страницPresentationVruchali ThakareОценок пока нет

- Thesis Statement On Lionel MessiДокумент4 страницыThesis Statement On Lionel Messidwham6h1100% (2)

- R917007195 Comando 8RДокумент50 страницR917007195 Comando 8RRodrigues de OliveiraОценок пока нет

- Procedure Manual - IMS: Locomotive Workshop, Northern Railway, LucknowДокумент8 страницProcedure Manual - IMS: Locomotive Workshop, Northern Railway, LucknowMarjorie Dulay Dumol80% (5)

- Project 2 Analysis of Florida WaterДокумент8 страницProject 2 Analysis of Florida WaterBeau Beauchamp100% (1)

- Addpac AP1000 DSДокумент2 страницыAddpac AP1000 DSEnrique RamosОценок пока нет

- Interventional Studies 2Документ28 страницInterventional Studies 2Abdul RazzakОценок пока нет

- COE301 Lab 2 Introduction MIPS AssemblyДокумент7 страницCOE301 Lab 2 Introduction MIPS AssemblyItz Sami UddinОценок пока нет

- Poster PresentationДокумент3 страницыPoster PresentationNipun RavalОценок пока нет

- AlligentДокумент44 страницыAlligentariОценок пока нет

- Def - Pemf Chronic Low Back PainДокумент17 страницDef - Pemf Chronic Low Back PainFisaudeОценок пока нет

- Btech CertificatesДокумент6 страницBtech CertificatesSuresh VadlamudiОценок пока нет

- Ancient To Roman EducationДокумент10 страницAncient To Roman EducationAnonymous wwq9kKDY4100% (2)

- Dial 1298 For Ambulance - HSBCДокумент22 страницыDial 1298 For Ambulance - HSBCDial1298forAmbulanceОценок пока нет

- KKS Equipment Matrik No PM Description PM StartДокумент3 страницыKKS Equipment Matrik No PM Description PM StartGHAZY TUBeОценок пока нет