Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Organ Technique

Загружено:

Hector RamirezИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Organ Technique

Загружено:

Hector RamirezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ORGAN TECHNIQUE

I learned a great deal from all my organ teachers, but I learned more about technique from Virgil Fox than from anyone else. Virgil was a wonderful teacher, by example, by his coaching skills, and by his drive. He practiced constantly. Therefore, his technique had to be practical and easy on the body. The more I perfected what he taught me, the easier and more enjoyable practicing and performing became. Although his technique is simple to describe, it was not simple to master. My first organ teacher, Louise Clary, who studied with Virgil at the Peabody Conservatory, introduced me to Virgil Fox when I was fourteen years old. I later studied with Earl Goodwin, organist of the United Methodist Church in Ridgewood, New Jersey, who also was a Fox student. During my six years of undergraduate studies, 1963-1969, I too had the privilege of studying with Dr. Fox, mostly during the summer months, and in his master classes, and following my graduation from Westminster Choir College, while I served as Director of Music and Organist of the Wesley United Methodist Church of Dover, Delaware. Unfortunately, my organ studies and my career as a professional church musician and recitalist came to an abrupt end when I was conscripted in 1970. Without dwelling on the rest of my personal musical history, I will attempt to summarize the technique I learned from Dr. Fox, which never failed to thrill me as a performing artist, because it helped me play even the most difficult music with control and confidence. A number of techniques learned from my other teachers are included.

ORGAN TECHNIQUE Use an arched hand and a flexible wrist. Keep your fingers on the keys. Virgil did not mean in the keys, but precisely on the keys. Keep the wrist down and the fingers curved. Play on the tips of your curved fingers. Never put a thumb on a black note. Play white notes close to the front of the black notes whenever possible, and play black notes on the front of the key. Fingering is of primary importance. Always play sequences with the same fingering. Keep your hand in position at all times and keep the wrist loose. Do not move the wrist left and right, for this moves the thumb out of position. The hand must always be flexible and relaxed. Press the keys to the bottom of the key fall. You are not dusting. This allows each pipe to speak and each note to be heard. This does not mean that the keys need to be played too hard. The release of each note is equally important. Both press and release are necessary for rhythm and clarity, whether you are playing legato or marcato. The faster a passage is played, the more detached the notes need to be, in order for the passage to be crisp and clean. You play the organ keyboard with your fingers, not the hand, not the arm, not the shoulder, as pianists play.

Push pistons with your thumbs keeping the other fingers above the keyboard. Only the thumb can push pistons with any certainty. Never use the end of another finger, for your hand will be hopelessly out of position when it returns to the keyboard. Never use a piston if you can make the changes by hand. Do not stiffen your back. A rigidly straight back is very tiring and can cause tension in the forearm, because of the lowered and flexible wrists. Sit comfortably in the center of the keyboard so that you can reach everything and never have to turn your entire body. This will allow you to play even extensive pedal passages with ease. The height of the organ bench should be so that you have to lift your toes off the pedal board, using the ankles, to move the feet around. The heel should be even with the pedals and gently touch them as the foot glides above them. If the bench is too high, the heels will be too high to play the pedals easily, and you will have to constantly perform a balancing act, which is not only tiring, but destroys pedal technique. Play the pedals as you walk. The knee follows the foot, i.e. the knee is above the ankle at all times. Play the pedals with alternating toes as much as possible. If the height of the bench is correct, you can play with your heel as needed without stretching the Achilles tendon. Play on the inside of the foot, never on the outside (except in the pedal scales as indicated below). Especially watch the placement of the right foot on the lower half of the pedalboard. Practice on the piano. Scales are very important. Virgil loved the B Major scale and we used to have races to see how fast we could play it. The hand position on the keys for the B Major scale is perfect for flying over the keys if the wrist is low, the fingers are curved, and you play on the keys with the tips of your fingers. When releasing chords, do not raise the wrist, only the fingers by lifting the wrist. Release chords together from the wrist, every note at the same time. Watch the pinkies, especially the pinkie of the left hand. Staccato chords need to be definite. Play to the bottom of the key as usual and release with the wrist. To give power to a chord, use an agogic accent. This is a slight holding up in the rhythm so that power can come on the next chord. Chords need air space to clear the way for the chord. To develop the agogic accent, metronome practice is essential until you can find the beat. Then and only then can an organist be rhythmic and not metronomic. The agogic accent only suspends the ongoing rhythm enough to create enough space for the announcement of the following chord, without stopping the beat. In a ritard (ritardando), the beat before the last beat (the penultimate beat) is the longest beat. When separating notes in a passage, especially in a sequence, the last notes of a passage, or perhaps just the penultimate note, should be held longer in order to emphasize the following downbeat. This should not alter the tempo, only the duration of the last notes. Never prolong the first beat of the following sequence.

When playing fast 16th notes in both hands, make the right hand notes detached, or even staccato. This may infuriate purists, but it will add clarity and interest and a wonderful forward movement. When playing contrapuntal music, you can bring out a voice by playing it with a different touch. Once the notes of a piece are learned and the fingering is mastered, practice with a metronome. This keeps you looking ahead. Adjust the speed so that difficult parts can be played accurately. You can practice with the beat or slightly behind the beat, but never ahead of the beat. Practice looking at the notes. Look at your hand only for jumps. Look before you leap. Look ahead in simpler parts of the music, and never look back. Concentrate more on the continuous line of harder passages. In performance, always slow down for difficult passages as you would slow down for icy spots on a road. Regain speed when the coast/road is clear. Fingering is very important. Every piece must be played with the same fingering every time. Every sequence must be fingered the same way. Learning the notes with correct fingering is essential before you can concentrate on the playing of the piece.

VIRGIL FOX MASTER CLASS BASIC TECHNIQUES PEDAL RULES: Keep the right foot a bit ahead of the left foot. The right foot crosses ahead of the left foot. Ankle action: Treat the ankle as the wrist is treated in piano technique when octaves are played. The knee does not move up and down. The knee travels freely to the right and to the left. (The line between the hip and the ankle remains straight.) Employ toe-to-toe action whenever possible. (This produces the greatest clarity.) Play the pedals as you should walk. Whenever three white notes are played with one foot, play them on the inside of the foot.

SLAP-RAISE EXERCISE (p = point = toe)

etc. p G p F p E C p B p A p etc. When playing the slap-raise exercise, there should be no action inside the shoe. Slap and raise the toes very high using equal time on the pedal and in the air. Each time the toes are raised they are brought over the next note. In the middle of the pedalboard, play in the middle of the foot, but a man with a large foot may have to play on the inside of the foot. People with large feet will also have to use less motion. Practice with the metronome set at about 66.

THUMB SCALE This is used in finger substitution. Place the thumb on C and push it forward and sideways to the next white note, either pushing the tip of the thumb to the next note or sliding the joint toward the body. You should be able to move the thumb so as to actually strike the adjacent notes on a piano.

PEDAL SCALES p = point, h = heel Right foot above the line. Left foot below the line. Play scales with knees together. O = outside of foot

I = inside of foot Major Scales: going up the cycle of fifths. (Scale)(Starting Note) O p ph ph I O I p php php ph I I

(c)

(d) p

hp ph

p ph

hp ph

php

(d) ph

p ph

hp ph

p ph

hph

(e) hp

p ph

p php

p ph

php

(e) hp

p php

p hp

p php

ph

(d#) php

p-p hp

p hp

p-p hp

php

F# Db

(c#) (db)

p p h p-p

p hp

p h p-p

p hp

php

Ab

(eb)

p php

p hp

p php

ph hp

Eb

(eb)

p php

p ph

p hp php p

Bb

(f) ph

hp ph

p ph

hp ph

ph

(f) ph

hp ph

p ph

hp ph

hp

Play the scales slow, medium and fast. Play also with accents. Accent by slapping the toe down. When descending, pull/slide the left foot back about 12 inches to make room for the right foot. To memorize, say aloud the right foot notes. Play the left foot notes as you walk. Keep the knees together most of the time, because the feet are together. Virgil could easily play the scales like lightning by twisting from the waist down with his hands free. When I practiced his pedal scales, I always held on to the front of the bench with both hands. At slow speed, all notes are connected. As speed is increased, the notes must become less legato. By the time a speed of fast 1/8 notes is reached, all notes are non-legato.

THE PEDAL CROMATIC SCALE All the notes are played with the point (toe), toe-to-toe, i.e. p-p-p-p, except F and C, which are played with the right heel. Keep the knees together.

PEDAL GLISSANDO This was always fun, especially at the end of the Middelschulte Perpetual Motion for Pedals Alone. Start with the outside of the right foot on the top white pedal and glide down the white notes on the outside of the right foot to the final note, which is played by the left foot. Look directly at the final note when you play it, because you certainly do not want to play the wrong final note with the full organ.

PIANO KEYBOARD PRACTICE THE B MAJOR SCALE:

Play the B Major scale accenting every 3rd beat, every 4th beat and every 6th beat. I also did every 5th beat. Practice slow (including very slowly), medium and fast, both hands, the entire length of the keyboard. Play 2 against 3, and 3 against 4. The reason for accenting is to place the accent on a different note with a different finger each time. In slow practice, accent very heavily and rest light. Minimize the action, especially at faster speeds. Raise the wrist before each accent. This relaxes the wrist, arm and fingers. ARPEGIOS: CEG CEA CFA CFAb CEG CEG# CEbAb CDAb CDbAb CEG Play one hand at a time the full length of the keyboard, slow, medium and fast. Play with a heavy and deliberate accent. Use fingers that are the most convenient: 123 542 124 542 124 532 etc.

MY DAILY PIANO EXERCISES THE VIRTUOSO PIANIST: SIXTY EXERCISES FOR PIANO. C. L. Hanon. PART I. No. 1. I played this every day, slow, medium, and fast, with fingers raised between each note as Hanon instructed. I always stretched my fingers before I started Hanon, as Virgil often did, using the second, third and fourth fingers of one hand to spread the fingers of the other hand by forcefully rubbing/pressing the three fingers of one hand through the finger joints of the other hand. If the skin between my fingers was dry, I would apply some moisturizing lotion. This spread the joints and made my fingers feel alive and relaxed. After PART I. No. 1, I selected two or three additional exercises from PART I each day, and played them very slowly, working my way eventually through all of PART I. I would then select 1 exercise from PART II, and play it slow, medium and fast, ending with No. 31. After that, I skipped to Legato Thirds, No. 50. I loved Hanons Chromatic scales in Minor Thirds. No. 51, Preparatory Exercise for the Scales in Octaves helped loosen my wrist, but I usually had to do this slowly, raising my wrist between each octave in

order to keep from tightening it. The rest of Hanon I left for the pianists, whose company I did not keep. THE PIANISTS WARMING-UP EXERCISES by Harold Bauer, Ex. 1. After the above exercises by Hanon and Bauer, I ran through the following repertoire as time permitted. Although Dr. Fox recommended his exercises for developing technique, he did not believe in keyboard exercises per se, and neither did I. Instead, I accumulated copies of favorite pieces in a notebook, and tore through them each day on the piano. As a result of using these pieces for daily piano practice, and using Virgils technique, I was always ready to play them at the drop of a hat: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. TOCCATA FOR THE MORNING OF EASTER, by Gilbert Martin. TOCCATA from Suite Gothique, Op. 25, by Leon Boellmann. TOCCATA from the Fifth Symphony by Charles Marie Vidor. CARILLON DE WESTMINSTER by Louis Vierne. PRELUDE from Sonata III by Marcel Dupre. A LESSON FOR THE ORGAN by William Selby, arranged by E. Power Biggs.

This kind of discipline marks the difference between physicians and attorneys, and performing organists. We do not exist only to practice, but also to perform and to play.

Вам также может понравиться

- On Organ Playing - Hints to Young Organists, with Complete Method for Pedal Scales and ArpeggiosОт EverandOn Organ Playing - Hints to Young Organists, with Complete Method for Pedal Scales and ArpeggiosРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Articulation and Pedaling - Ina GrapenthinДокумент4 страницыArticulation and Pedaling - Ina GrapenthinOpeyemi ojoОценок пока нет

- Idiots Guide To Organ RegistrationДокумент8 страницIdiots Guide To Organ RegistrationJoshuaNichols100% (2)

- Moorman - Chalenge Teaching Organ To YouthДокумент9 страницMoorman - Chalenge Teaching Organ To Youthmanuel1971100% (1)

- Organ Works - V. LubeckДокумент57 страницOrgan Works - V. LubeckAlessio Carrus100% (3)

- Hymn Accompaniment - Organ Playing - HullДокумент286 страницHymn Accompaniment - Organ Playing - HullChurch Organ Guides96% (28)

- Transformations-Preludes and PostludesДокумент39 страницTransformations-Preludes and PostludesOskr ArTuro100% (2)

- By U Organ Workshop Packet 2017Документ34 страницыBy U Organ Workshop Packet 2017Adrian100% (6)

- Dupre, Marcel - Method For The OrganДокумент81 страницаDupre, Marcel - Method For The OrganEdgar Bablumyan100% (20)

- The Technique and Art of Organ Playing (Dickinson, Clarence)Документ276 страницThe Technique and Art of Organ Playing (Dickinson, Clarence)Ambroise100% (7)

- Organ BookДокумент23 страницыOrgan BookMyc-lОценок пока нет

- Soderlund - Young Person's Guide To The Pipe OrganДокумент14 страницSoderlund - Young Person's Guide To The Pipe OrganWaltWritmanОценок пока нет

- Hector Parr's Essays Practising The OrganДокумент10 страницHector Parr's Essays Practising The Organedenlover100% (2)

- Beginning OrganДокумент18 страницBeginning OrganRogerio Lima89% (9)

- Four Columns On Pedal Playing by Gavin Black, 2007-08Документ17 страницFour Columns On Pedal Playing by Gavin Black, 2007-08AdrianОценок пока нет

- Playing The Church Organ: Book 1Документ11 страницPlaying The Church Organ: Book 1Isaac Nicholas NotorioОценок пока нет

- The CompleteTHE COMPLETE CHURCH ORGANIST Church OrganistДокумент62 страницыThe CompleteTHE COMPLETE CHURCH ORGANIST Church OrganistColleen Van Schalkwyk100% (9)

- Dupré - Vêpres Du Commun Des Fêtes de La Sainte-Vierge, Op. 18 (Organ)Документ50 страницDupré - Vêpres Du Commun Des Fêtes de La Sainte-Vierge, Op. 18 (Organ)DerKomponist100% (2)

- Marcel Dupré EsquissesДокумент31 страницаMarcel Dupré EsquissesOlivier Eugène Prosper Charles MessiaenОценок пока нет

- Guilmont Practical Organist BK 1Документ118 страницGuilmont Practical Organist BK 1Bridget O'Leary100% (17)

- Flor Peeters - Organ Book PDFДокумент122 страницыFlor Peeters - Organ Book PDFLouie Angelo Oca100% (5)

- Bach's Organ Registration - W. SumnerДокумент83 страницыBach's Organ Registration - W. Sumnercedric100% (5)

- Improvisation Organ Four ComposersДокумент30 страницImprovisation Organ Four ComposersJoaquim MorenoОценок пока нет

- Teach The OrganДокумент44 страницыTeach The Organmauro9601595100% (2)

- The Organ ReedДокумент152 страницыThe Organ ReedcsabezsОценок пока нет

- Cinema OrganДокумент32 страницыCinema Organmifre75% (4)

- Organ Registration - 272-Pages - Comprehensive Guide by Everette E Trudette - 1919Документ272 страницыOrgan Registration - 272-Pages - Comprehensive Guide by Everette E Trudette - 1919Church Organ Guides100% (12)

- Church Music - The Pastoral OrganistДокумент9 страницChurch Music - The Pastoral OrganistDennis56% (9)

- L'Organiste - CompilationДокумент67 страницL'Organiste - Compilationrichime1795% (22)

- Organ RegistrationДокумент7 страницOrgan RegistrationErma Sandy LeeОценок пока нет

- Lanquetuit - Toccata in D 2.0Документ7 страницLanquetuit - Toccata in D 2.0theotdf25% (4)

- Hymn Accompaniment - Reed Organs - 1910Документ28 страницHymn Accompaniment - Reed Organs - 1910Church Organ Guides80% (5)

- Sacred Music, 119.3, Fall 1992 The Journal of The Church Music Association of AmericaДокумент33 страницыSacred Music, 119.3, Fall 1992 The Journal of The Church Music Association of AmericaChurch Music Association of America100% (1)

- Archer-12 Organ Preludes Op2Документ61 страницаArcher-12 Organ Preludes Op2Jerald Franklin Archer100% (6)

- Improvisation On The OrganДокумент69 страницImprovisation On The Organppiccolini100% (22)

- Organ Orchestra ListДокумент12 страницOrgan Orchestra Listschroeder76Оценок пока нет

- Christmas Music For The OrganДокумент48 страницChristmas Music For The OrganJuanma Santos100% (23)

- Luebeck Vincent ORGAN WORKSДокумент55 страницLuebeck Vincent ORGAN WORKSIvan Rakonca100% (4)

- The New Ward Organist PacketДокумент57 страницThe New Ward Organist PacketWilliamPearsonОценок пока нет

- PDF PDFДокумент192 страницыPDF PDFAdrianОценок пока нет

- Julius Andre's Organ BookДокумент90 страницJulius Andre's Organ Bookmontuno80% (5)

- Liber Organi - Dalla Libera - 01Документ87 страницLiber Organi - Dalla Libera - 01Carmine RiccoОценок пока нет

- Prélude, Adagio Et Choral Varié Sur Le Thème Du 'Veni Creator', Op 4Документ1 страницаPrélude, Adagio Et Choral Varié Sur Le Thème Du 'Veni Creator', Op 4Vincenzo NocerinoОценок пока нет

- Manual OrganistaДокумент27 страницManual OrganistaCarmelo Hoyos100% (3)

- Samuel Barber's Organ MusicДокумент15 страницSamuel Barber's Organ Musicdolcy lawounОценок пока нет

- Allegro Music Organ CatalogueДокумент62 страницыAllegro Music Organ Cataloguescribdzzzzz80% (5)

- 39087009930571score PDFДокумент286 страниц39087009930571score PDFdenieren 3421Оценок пока нет

- 540-604 - Organ Accompaniment of TheChoral Service - 00 - CADENCIAS MODALESДокумент86 страниц540-604 - Organ Accompaniment of TheChoral Service - 00 - CADENCIAS MODALESCarlos Gutiérrez100% (1)

- Fortyfour SchneiderДокумент56 страницFortyfour SchneiderJosué Reséndiz MendozaОценок пока нет

- Vogel - North German Organ Building of Late 17th CДокумент6 страницVogel - North German Organ Building of Late 17th CBenjamin MolonfaleanОценок пока нет

- The Wanamaker Grand Organ PDFДокумент18 страницThe Wanamaker Grand Organ PDFAfonso24Оценок пока нет

- Let's Get Rid of The Wrong Pralltriller!Документ6 страницLet's Get Rid of The Wrong Pralltriller!zdanakasОценок пока нет

- Organ Transcriptions in The Nineteenth Century Part 1Документ18 страницOrgan Transcriptions in The Nineteenth Century Part 1api-237576067100% (1)

- Bach CPE Organ MusicДокумент85 страницBach CPE Organ Musicphroddy100% (6)

- The Art of ImprovisationДокумент95 страницThe Art of ImprovisationAngelo Conto100% (4)

- Teaching Organ in An Holistic Manner LaverДокумент6 страницTeaching Organ in An Holistic Manner Lavermanuel1971Оценок пока нет

- Saint Peter S Postlude For OrganДокумент10 страницSaint Peter S Postlude For OrganDavid Garrison100% (3)

- Berlioz Toccata ORGANДокумент2 страницыBerlioz Toccata ORGANmusiccentersf100% (1)

- Tracing Seven Hundred Years of Organ RegistrationДокумент45 страницTracing Seven Hundred Years of Organ RegistrationAngel AngelinoОценок пока нет

- Theatre SportsДокумент3 страницыTheatre SportsdonОценок пока нет

- 651307p ManualДокумент16 страниц651307p Manuallacc2211Оценок пока нет

- MastersДокумент213 страницMastersadrian4fanОценок пока нет

- Academic Fanfare Tuba CompleteДокумент4 страницыAcademic Fanfare Tuba CompleteRenato SouzaОценок пока нет

- Take My Life and Let It Be PDFДокумент1 страницаTake My Life and Let It Be PDFMeliОценок пока нет

- The Classic Project Colección 1 Al 10Документ23 страницыThe Classic Project Colección 1 Al 10gatochalet50% (2)

- Ulus 10551Документ34 страницыUlus 10551Chass OokaОценок пока нет

- Laporan Customer RO 2023 12 05-02 06 38Документ13 страницLaporan Customer RO 2023 12 05-02 06 38sucikurniati94Оценок пока нет

- GJLDBДокумент7 страницGJLDBanon_500950832Оценок пока нет

- Tram 2 PreampДокумент30 страницTram 2 Preampdecky999100% (1)

- Personal Response Questions 400Документ60 страницPersonal Response Questions 400Anonymous wfZ9qDMNОценок пока нет

- Below Are The Key Guide Questions That You ShouldДокумент3 страницыBelow Are The Key Guide Questions That You ShouldHAKDOGОценок пока нет

- Jingle Bells: Presto (Документ3 страницыJingle Bells: Presto (GrilloBarroteОценок пока нет

- Twelve Communion Propers For Lent: SATB, OrganДокумент37 страницTwelve Communion Propers For Lent: SATB, OrganChurch Music Association of America100% (3)

- Agosto 8Документ3 страницыAgosto 8Jisbe Milagros HuaranccaОценок пока нет

- FonetikaДокумент26 страницFonetikaangelinaagОценок пока нет

- 1550nm Internal Optical TransmitterДокумент4 страницы1550nm Internal Optical TransmitterWOLCK Liwen LeiОценок пока нет

- Pioneer Pdp434p Plasma TV SM (ET)Документ95 страницPioneer Pdp434p Plasma TV SM (ET)Muskegon Michigan100% (1)

- Mri Artifacts FinalДокумент44 страницыMri Artifacts FinalSunny SbaОценок пока нет

- Philips Chassis Tpm5.1e-La PDFДокумент70 страницPhilips Chassis Tpm5.1e-La PDFPC MediaPointОценок пока нет

- Wright, Michael - Playwriting in ProcessДокумент126 страницWright, Michael - Playwriting in Processlaura100% (1)

- The Good Ole DaysДокумент4 страницыThe Good Ole DaysKertrankaОценок пока нет

- The Miracle of Mindfulness - An Introduction To The Practice of Meditation (1999) by Thich Nhat HanhДокумент31 страницаThe Miracle of Mindfulness - An Introduction To The Practice of Meditation (1999) by Thich Nhat HanhaaaaОценок пока нет

- Highspeed Signal Processing in A Programmable Propagation SimulatorДокумент7 страницHighspeed Signal Processing in A Programmable Propagation SimulatortkОценок пока нет

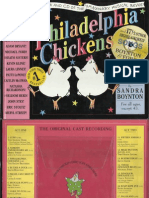

- Philadelphia Chickens by Sandra BoyntonДокумент70 страницPhiladelphia Chickens by Sandra BoyntonIoana Alexandru83% (6)

- Milt HintonДокумент5 страницMilt HintonManzini MbongeniОценок пока нет

- SRT 8114Документ2 страницыSRT 8114bejanОценок пока нет

- 0 19 438425 X AДокумент2 страницы0 19 438425 X ASebastian2007Оценок пока нет

- Beyond Beethoven and The Boyz Women's Music in Relation To History and CultureДокумент8 страницBeyond Beethoven and The Boyz Women's Music in Relation To History and CultureLila LilaОценок пока нет

- ARIA Telecom Company - DialerДокумент9 страницARIA Telecom Company - DialerAnkit MittalОценок пока нет