Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nathan Jurgenson & PJ Rey - Comment On Sarah Ford's Reconceptualization of Privacy and Publicity'

Загружено:

P.J. ReyОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nathan Jurgenson & PJ Rey - Comment On Sarah Ford's Reconceptualization of Privacy and Publicity'

Загружено:

P.J. ReyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nathan Jurgenson & P. J.

Rey

COMMENT ON SARAH FORDS RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF PRIVACY AND PUBLICITY

Sarah Fords recent article, Reconceptualizing the Public/Private Distinction in the Age of Information Technology demonstrates how social media shifts our understanding of privacy and publicity and proposes a continuum model instead of a simple dichotomy. In this commentary, we argue that Fords proposed model does not go far enough to break down the problematic dichotomous thinking and propose a further reconceptualization of privacy and publicity as a dialectic. Keywords sociology; ICTs; surveillance; privacy; publicity; social change; Web 2.0; continuum; dialectic; theory (Received 12 July 2011; final version received 24 August 2011) Social media force us to revisit many of the fundamental concepts through which we make sense of our social reality not the least of which are our notions of privacy and publicity. The media frequently reports on how these new forms of publicity produce troubling results (e.g., Facebook privacy issues, the Anthony Weiner scandal, etc.). Academic research, such as danah boyds (2010, 2011a, 2011b) work, has found a better balance in describing both the potential pitfalls as well as the benefits of online visibility. However, much work remains to be done in theorizing the shifting relationship between publicity and privacy in digital age. In the June 2011 issue of Information, Communication & Society, Sarah Ford (2011) argued that privacy and publicity should not be thought of as a dichotomy (as these categories have been traditionally treated), but instead as a continuum, where an infinite number of combinations exist between the poles. We wish to critique Fords continuum model in two ways: (1) Her conclusions are somewhat contradictory and do not neatly follow from the evidence presented and (2) this is because her new model does not make the radical break with the traditional conceptualizations of publicity/privacy that is required to fully capture the

Information, Communication & Society Vol. 15, No. 2, March 2012, pp. 287 293 ISSN 1369-118X print/ISSN 1468-4462 online # 2012 Taylor & Francis http://www.tandfonline.com http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2011.619552

288

INFORMATION, COMMUNICATION & SOCIETY

enmeshed nature of the concepts. Alternatively, we propose that, in the digital age, privacy and publicity might be better understood as a dialectic. In her conclusion, Ford (p. 14) clearly expresses the logical tension that we believe characterizes her model, when she states that: The public and private realms have bled over into one another, and can no longer be treated as a dichotomous pair [. . .] a more fruitful conception of the public/private realms is one that treats them as anchors on either end of a continuum, with liminal categories being created and destroyed as needed. The line between public and private has become blurry; these concepts are no longer polar opposites [. . .]. The problem highlighted in this passage is that privacy and publicity are described as being anchors on either end of a continuum, while simultaneously no longer being polar opposites. Yet, by definition, the ends (or poles) of a continuum must be (polar) opposites. Presumably, Fords intent was to say that publicity and privacy are no longer discrete categories that a particular space or activity need not be only public or only private, that, instead, we can have something that quasi-public and quasi-private. The logic of this argument is similar, by analogy, to saying that, while things can be black or white, they can also be many shades of grey. This is made explicit in Fords Figure 1. Fords observation that we have, historically, treated the categories of publicity and privacy as discrete is important, and social media has, undoubtedly, rendered this simple binary obsolete. However, we find that the continuum model is still too reductive to sufficiently account for even the examples Ford provides. This is because continua imply a zero-sum balance. If, for example, I am mixing a gallon of paint, two-quarters of black and two-quarters of white will give me medium grey. If, however, I want the paint to be darker, I must replace some of the white in the mixture with black. To have maximally dark paint, I

FIGURE 1

Sarahs Fords continuum model of privacy and publicity.

COMMENT ON SARAH FORDS RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF PRIVACY AND PUBLICITY

289

must add only black to the can at the expense of adding any white. Because our phenomena of interest (publicity and privacy) are qualitative variables, we can improve the analogy by saying that increasing the intensity of the darkness of our paint requires diminishing the intensity of the lightness of our paint. The problem with the continuum model is that an increase in publicity does not necessarily imply a decrease in privacy or vice versa. In fact, we need only consider some of the examples that Ford provides. She cites danah boyds (2011b) notion of social steganography as a reason why we need a continuum model of privacy/publicity. However, this example is an evidence of precisely why the continuum model does not work. Social steganography refers to the practice of social media users hiding messages in plain sight by posting information publically that seems innocuous unless a particular reader has certain information that allows them to decode the message. For instance, a teen might post what appear to be simple song lyrics, but to a group in the know, it might signal that the person who posted the content has just experienced a painful breakup. Thus, a single post can be highly public in that anyone can read or access the information put forth, even if it seems cryptic or, even, altogether meaningless, while conveying a very controlled and personal and thus very private message to those who get it. Social stenography demonstrates that a single act of communication can be at once very public as well as quite private. To return to our previous analogy, it can be both intensely black and intensely white without dissolving into grey. We reach a similar conclusion when reviewing a second practice described by boyd (2011a) that is often called white-walling. This is a practice whereby social media users post information and allow others to post information on their social media profile (usually Facebook) and then, periodically, delete everything. A person can be hyper-public by posting a lot of information about oneself and others. And then, by deleting it all at the end of the day, the same person also practices intensely private behaviour. The continuum model would suggest that the white-wall-ers behaviour is comparable to a person who posts limited amounts of information on social media. It leads us to lose sight of the fact that those who white-wall are devoting far more energy to ensuring both publicity as well as privacy. In fact, there is a major qualitative difference between the white-wall-er and the limited user: The limited user is likely to see only limited benefits from using social media while being exposed to only limited risk, whereas, the white-wall-er maximizes the benefits of social media while still mitigating its risks. These two user-types cannot be grouped together as the continuum model would suggest.

Not a continuum, a dialectic

In contrast to Fords continuum model, we argue that privacy and publicity produce a dialectic that each concept implies the other. Before we proceed

290

INFORMATION, COMMUNICATION & SOCIETY

to advance this argument, we wish to make clear that we are not claiming that the terms public and private no longer make sense when separated. In the abstract, we agree with Nippert-Eng (2010) that these discrete concepts can be deployed as Weberian ideal types (i.e., conceptual guides that are helpful for theorizing), even if the phenomena never manifest themselves in ideal typical forms. Nevertheless, we find that viewing privacy and publicity as opposite ends, poles, or anchors on a continuum is often misleading. We, thus, call for a model that begins to deconstruct this binary thinking. When theorizing about the breaking, or deconstructing, of previously held binaries it is often useful to look to post-structural and post-Modern thought. One such thinker that we find useful here is Georges Bataille (who, subsequently, influenced Jean Baudrillard). Bataille (1988, 2004; Richardson 1994), a philosopher and fiction author notorious for his pornographic writing, argued that every instance of knowledge is simultaneously an instance of non-knowledge. Simply, and not precisely the way Bataille uses the concept, each time you learn something new, you also learn more about what you do not know. For example, with each new scientific discovery, we might learn something new, but, simultaneously, we also start asking questions that we never could have before.1 Each time we learn something new (knowledge) the stock of what we do not know (non-knowledge) grows ever larger. Following Bataille, philosopher Baudrillard (1983/1990) develops the concepts obscenity and seduction around the knowledge/non-knowledge relationship. Obscenity is the drive to reveal all and expose things in full, whereas seduction is the process of strategically withholding in order to create magical and enchanted interest (what he calls the scene opposed to the obscene). That is, non-knowledge is the seductive and magical aspect of knowledge. Using Baudrillards metaphor, we might say that burlesque is seductive because each layer removed reveals something new that is still concealed, whereas pornography is said to be obscene because it immediately reveals everything, often in close-up. Drawing on Baudrillards metaphor and borrowing a term from Smith (2009) we might say that self-presentation on social media takes the form of a fan-dance, a space where we both reveal and conceal, never showing too much, else we have given it all away, but always enticing by strategically concealing the right bits at the right time. Each status update suggests that which has been left out. Bataille typically discussed non-knowledge as an ecstatic inner-experience, and with Baudrillards contribution we can say that the inner-experience is one of seduction, enchantment, and enticement. Thus, publicity is understood to be always rife with its conceptual opposite: concealment. A status update is a public act, but it also expresses its conceptual opposite as it obscures the rich detail that lies between each of the updates. How does each update relate to the next? What else do they imply? When posting a picture publicly, one is also, potentially, concealing information such as: Who took the picture? Who else was there? Where was this? How does this photo relate to the others in the album?

COMMENT ON SARAH FORDS RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF PRIVACY AND PUBLICITY

291

Which photos were deleted/never posted? What wasnt photographed in the first place? While some of this information may be provided with the photo, the information cannot ever be exhaustive (remember, more information only leads to more new questions). In short, the screen ever contains only a very partial story. As the conceptual antithesis of publicity, privacy does not simply consist of behaviours like hiding identities or simply posting nothing at all. Rather, when one reveals something in a post, even when using ones real name, there is always a private layer of information that is concealed, yet implicitly suggested. As the conceptual antithesis of privacy, publicity (in its absence or its potentiality) lends private information value and importance. That is to say, when we share part of a story publically, the rest of the story becomes more valuable to those who have private access. This understanding has always been implicit in gossip. For example, when we disclose a particularly juicy detail of our personal life to a close confidant, the value of that information is twofold: (1) we are signalling that our relationship with the confidant is important by giving them exclusive, private access, and (2) our confidant is doubly rewarded with our implicit permission to make that information public and, subsequently, to bask in all the interest and attention. Similarly, as Davis (2011) notes, friend purges (i.e., the practice of periodically deleting all but the people one feels closest to) are a public declaration of who does and does not merit access to ones private information. This very public act, in fact, intensifies privacy. The reformulation we have offered, one that views privacy and publicity as intertwined (boyd, 2011c) and co-implicated, suggests a dialectic understanding. The dialectic model asserts that publicity and privacy do not always come at the expense of one another but, at times, can be mutually reinforcing (Figure 2). The actions that promote and support publicity are not cancelled out by those that promote and support privacy, nor is the inverse true. Instead, information sharing that is characterized by intense concern for both publicity and privacy must be viewed as qualitatively distinct from those situations where little concern is devoted to either. This realization may proved to be useful in understanding the differences, for example, in the ways in which social media is engaged by digital natives versus digital migrants. The media tend to describe natives as obsessed with publicity and migrants as more concerned with privacy. Our new model would allow us to offer an alternative hypothesis that natives are, in fact, more concerned with and more adept at managing both publicity and privacy (of course, such a claim demands empirical testing).

FIGURE 2

Proposed dialectical model of privacy and publicity.

292

INFORMATION, COMMUNICATION & SOCIETY

There is a broad consensus, both within and outside academia, that the relationship between publicity and privacy is changing in light of recent developments in communication technologies. Ford has made an important contribution to our understanding of the historical context surrounding this shift and has helped to formalize our assumptions about these two social phenomena. We call for an ongoing discussion about publicity and privacy towards the development of future theoretical refinements. While it was impossible to fully develop a dialectical model in this short commentary piece, we hope to have made a compelling case as to why the continuum model remains inadequate and to have stimulated further consideration of how a dialectic (or other) approach might better capture privacy and publicity online.

Note

1 This insight is central to the Socratic method which brings wisdom by leading pupils to formulate questions that themselves are only the precondition to the next set of questions. In fact, the Oracle of Delphi was purported to have called Socrates, the wisest man in Athens, because he was the only person who knew what he did not know.

References

Bataille, G. (1988) Inner Experience, Translated by Leslie Anne Boldt. State University of New York, New York. Bataille, G. (2004) The Unfinished System of Nonknowledge, Translated by Stuart Kendall and Michelle Kendall. University of Minnesota Press, MN. Baudrillard, J. (1983/1990) Fatal Strategies, Semiotext(e), Los Angeles, CA. boyd, d. (2010) Social Network Sites as Networked Publics: Affordances, Dynamics, and Implications, in Networked Self: Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, ed. Zizi Papacharissi, pp. 3958. boyd, d (2011a) Networked Privacy, talk given at Personal Democracy Forum, New York, NY, 6 June. boyd, d. (2011b) Social steganography: privacy in networked publics, aper presented at ICA on 28 May, 2011, Boston, MA. boyd, d. (2011c) Privacy, publicity intertwined, Keynote presented at Theorizing the Web 2011 on April 9, University of Maryland. Davis, J. (2011) Beyond the popularity contest: constructions of exclusivity on Facebook, paper presented at Theorizing the Web 2011 on 9 April, University of Maryland. Ford, S. (2011) Reconceptualizing the public/private distinction in the age of information technology, Information, Communication & Society, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 550567.

COMMENT ON SARAH FORDS RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF PRIVACY AND PUBLICITY

293

Richardson, M. (1994) Georges Bataille, Routledge, London. Smith, M. (2009) A link to social media network visualization: picturing online relations and roles, paper presented at iSchool Colloquium on September 15, University of Maryland.

Nathan Jurgenson is a graduate student in the department of Sociology at the University of Maryland. Address: University of Maryland, College Park, USA. [email: nathanjurgenson@gmail.com] P. J. Rey is a graduate student in the department of Sociology at the University of Maryland. Address: University of Maryland, College Park, USA. [email: pjrey.socy@gmail.com]

Вам также может понравиться

- Women As Goddess - Camille Paglia Tours Strip ClubsДокумент5 страницWomen As Goddess - Camille Paglia Tours Strip ClubsP.J. Rey100% (4)

- ADS L1530 Speakers Owners Manual (1981)Документ12 страницADS L1530 Speakers Owners Manual (1981)P.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- PJ Rey - Alienation, Exploitation & Social Media PDFДокумент23 страницыPJ Rey - Alienation, Exploitation & Social Media PDFP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- PJ Rey - The Myth of CyberspaceДокумент15 страницPJ Rey - The Myth of CyberspaceP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

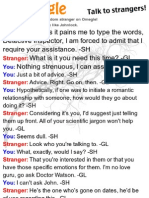

- Sherlock RomanceДокумент1 страницаSherlock RomanceP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- The Fan Dance: How Privacy Thrives in An Age of Hyper PublicityДокумент17 страницThe Fan Dance: How Privacy Thrives in An Age of Hyper PublicityP.J. Rey50% (2)

- Omegle - Sherlock ScarsДокумент1 страницаOmegle - Sherlock ScarsP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- Turner ASA 2012 SlideДокумент2 страницыTurner ASA 2012 SlideP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- Event PageДокумент2 страницыEvent PageP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- Social Media and Revolutionary MovementsДокумент13 страницSocial Media and Revolutionary MovementsP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- GMU Public Sociology Presentation - The Academy & Social MediaДокумент31 страницаGMU Public Sociology Presentation - The Academy & Social MediaP.J. ReyОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Build The Tango: by Hank BravoДокумент57 страницBuild The Tango: by Hank BravoMarceloRossel100% (1)

- MMB To OIG Request For Further Investigation 6-27-23Документ2 страницыMMB To OIG Request For Further Investigation 6-27-23maustermuhleОценок пока нет

- Peralta v. Philpost (GR 223395, December 4, 2018Документ20 страницPeralta v. Philpost (GR 223395, December 4, 2018Conacon ESОценок пока нет

- The Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernanceДокумент12 страницThe Role of The Board of Directors in Corporate GovernancedushyantОценок пока нет

- Barber ResumeДокумент6 страницBarber Resumefrebulnfg100% (1)

- F4-Geography Pre-Mock Exam 18.08.2021Документ6 страницF4-Geography Pre-Mock Exam 18.08.2021JOHNОценок пока нет

- Delivery ReceiptДокумент28 страницDelivery Receiptggac16312916Оценок пока нет

- Annex E - Part 1Документ1 страницаAnnex E - Part 1Khawar AliОценок пока нет

- Where The Boys Are (Verbs) : Name Oscar Oreste Salvador Carlos Date PeriodДокумент6 страницWhere The Boys Are (Verbs) : Name Oscar Oreste Salvador Carlos Date PeriodOscar Oreste Salvador CarlosОценок пока нет

- Forge Innovation Handbook Submission TemplateДокумент17 страницForge Innovation Handbook Submission Templateakil murugesanОценок пока нет

- Cat Enclosure IngДокумент40 страницCat Enclosure IngJuan Pablo GonzálezОценок пока нет

- Hse Check List For Portable Grinding MachineДокумент1 страницаHse Check List For Portable Grinding MachineMD AbdullahОценок пока нет

- Spring 2021 NBME BreakdownДокумент47 страницSpring 2021 NBME BreakdownUmaОценок пока нет

- 100 Demon WeaponsДокумент31 страница100 Demon WeaponsSpencer KrigbaumОценок пока нет

- Napoleons Letter To The Jews 1799Документ2 страницыNapoleons Letter To The Jews 1799larsОценок пока нет

- Soal Passive VoiceДокумент1 страницаSoal Passive VoiceRonny RalinОценок пока нет

- Sand Cone Method: Measurement in The FieldДокумент2 страницыSand Cone Method: Measurement in The FieldAbbas tahmasebi poorОценок пока нет

- DharmakirtiДокумент7 страницDharmakirtialephfirmino1Оценок пока нет

- Precontraint 502S2 & 702S2Документ1 страницаPrecontraint 502S2 & 702S2Muhammad Najam AbbasОценок пока нет

- TOEFLДокумент27 страницTOEFLAmalia Nurhidayah100% (1)

- The Book of Mark: BY Dr. R. Muzira Skype: Pastorrobertmuzira Cell: 0782 833 009Документ18 страницThe Book of Mark: BY Dr. R. Muzira Skype: Pastorrobertmuzira Cell: 0782 833 009Justice MachiwanaОценок пока нет

- Answer To FIN 402 Exam 1 - Section002 - Version 2 Group B (70 Points)Документ4 страницыAnswer To FIN 402 Exam 1 - Section002 - Version 2 Group B (70 Points)erijfОценок пока нет

- MANILA HOTEL CORP. vs. NLRCДокумент5 страницMANILA HOTEL CORP. vs. NLRCHilary MostajoОценок пока нет

- ALA - Application Guide 2023Документ3 страницыALA - Application Guide 2023Safidiniaina Lahatra RasamoelinaОценок пока нет

- Skans Schools of Accountancy CAF-8: Product Units RsДокумент2 страницыSkans Schools of Accountancy CAF-8: Product Units RsmaryОценок пока нет

- Drimaren - Dark - Blue HF-CDДокумент17 страницDrimaren - Dark - Blue HF-CDrajasajjad0% (1)

- 08.08.2022 FinalДокумент4 страницы08.08.2022 Finalniezhe152Оценок пока нет

- Sibeko Et Al. 2020Документ16 страницSibeko Et Al. 2020Adeniji OlagokeОценок пока нет

- A Game Is A Structured Form of PlayДокумент5 страницA Game Is A Structured Form of PlayNawa AuluddinОценок пока нет

- 1 Reviewing Number Concepts: Coursebook Pages 1-21Документ2 страницы1 Reviewing Number Concepts: Coursebook Pages 1-21effa86Оценок пока нет