Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Toronto Notes Neurology 2008

Загружено:

Alina Elena TudoracheИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Toronto Notes Neurology 2008

Загружено:

Alina Elena TudoracheАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

N

Neurology

Eduard Bercovici, Lauren Gerard and Ognjen Papic, chapter editors

Lawrence Aoun and Sam Silver, associate editors

Jeremy Adams, EBM editor

Dr. Cheryl Jaigobin and Dr. Liesly Lee, staff editors

Basic Anatomy Review 2

Differential Diagnosis of Common

Presentations

Review of Neurological Examination

Lesion Localization

3

Diagnostic Investigations

Lumbar Puncture

6

Altered Level of Consciousness

Evaluation of Patient

Coma

Persistent Vegetative State

Brain Death

7

Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy

Seizure

Status Epilepticus

8

Behavioural Neurology

Acute Confusional State/Delirium

Dementia

Alzheimer's Disease

Lewy Body Disease

Frontotemporal Dementia

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

Aphasia

Dysarthria

Dysphagia

Apraxia

Agnosia

13

Cranial Nerve Deficits 20

Neuro-Ophthalmology

Acute Visual Loss

Optic Neuritis

Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

Amaurosis FugaxfTlA

Optic Disc Edema

Abnormalities of Visual Field

Abnormalities of Eye Movements

Disorders of Lateral Gaze

Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia (INO)

Diplopia

Abnormalities of Pupils

Relative Afferent Pupillary Defect

Horner's Syndrome

Anisocoria

24

Movement Disorders

Localization of Extrapyramidal Disorders

Function of the Basal Ganglia

Parkinsonism

Parkinson's Disease (PO)

Wilson's Disease

Tremor

Essential Tremor

Chorea

Huntington's Disease

Dystonia

Myoclonus

Tic Disorders

Tourette's Syndrome

29

Toronto Notes 2008

Neuromuscular Disease 38

Overview

Motor Neuron Disease

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

Other Motor Neuron Disease

Peripheral Neuropathies

Clinical Approach

Mononeuropathy Multiplex

Diffuse Symmetric Polyneuropathies

Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS)

Diabetic Neuropathies

Para neoplastic Neuropathies

Neuromuscular Junction Diseases

Clinical Approach

Myasthenia Gravis

Lambert Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome

Myopathies

Clinical Approach

Polymyositis/Dermatomyositis

Myotonic Dystrophy

Duchenne and Becker Muscular Dystrophy

Cerebellar Disorders 47

Approach to Cerebellar Disorders

Acquired Cerebellar Disorders

Hereditary Ataxias

Vertigo 48

Gait Disturbances 49

Disorders of Balance

Disorders of Locomotion

Pain Syndromes 50

Approach to Pain Syndromes

Neuropathic Pain

Tic Douloureux

Postherpetic Neuralgia

Complex Regional Pain Syndromes

Thalamic Pain (Dejerine Roussy Syndrome)

Headache 54

Clinical Approach to Headaches

Migraine Headaches

EpisodicTension-Type Headache

ChronicTension-Type Headache

Cluster Headache

eNS Infections 107

Spinal Cord Syndromes NS24

Stroke 57

Ischemic Stroke

Hemorrhagic Stroke

Treatment of Stroke

Multiple Sclerosis 64

Common Medications 66

Summary Key Questions 67

References 68

Neurology Nl

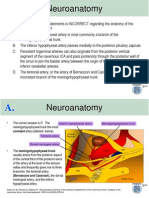

N2 Neurology Basic Anatomy Review Toronto Notes 200S

See functional Neuroanatomy

software Basic Anatomy Review

see also Neurosurgery, NS21 for Dennatome/Myotome infonnation

sensory cortex

upper motor neurons

in I1KItor

spinothalamic traci

Figure 1. Corticospinal Motor Pathway

" I

{lower limb & tn.<l'Ikl _ ftr.>l-order

of ....')

sensory neuron ""..-I '.,1.'

second-order

(uppelhmbl

cortex

sensory neuron within 12 spinal levels of their entry.

axons offirsl order neurons synapse onto

second order neurons, whose aXOIlS

then decussate before ascending as

the spinothalamic tract

Figure 5. SpinothalamicTract

o Cerebrocerebellum

Culmen

[J} Spinocerebellum

Vestibulocerebellum

onpUlfrom

upper limb

dorlillloot

grKlhs

ganghon

5

hmb&trunk @)

Figure 2. DiscriminativeTouch Pathway From Body

sensory cortex

face region

,Sagittal section through brainstem and cerebellum Flocculus Tormls Nodulus

Anre,ia, view

Figure 6. Cerebellum

chIef sensory

trlgenunal nucleus

Figure 3. DiscriminativeTouch Pathway From Face

Pons Midbrain Medulla

I. Corticosplnaltraet Ponril'lt"l'lucleus 1. InterpeduflCuiarfossa

1. Llteralsploolhalam,ctracr Abducens nerve fibres 2. Occulomotor lilt) nerve fibres

sensory corte"

and spinotectaillbres Corticosplnallract and 3. Cerebral peduncle

facE." region

3. Decussation 01 l'lle<h;,llemnivus cOrtkOI'lUcleilrfibtes 4 .'iubslanl,an'gr<l

... Reticularfolm.tlIon . 5. Rednucleu5

S. Nucleus of spinallracl S. Nucleus of fadal (VII) nerve (mOlor) 6. Edinger_estphal nucleI

lV) nerve (descending) 6. Facial (Villnervefib.es 7. OCculomotor (III) nucleus

6. Spinal IIKI of trigeminal (Vl nerve 7. rflgeminal {V) nerve fibres complex {motofl

7. Nucleuscul'lealus II Nucleus of abducens (VI) nerve 8. MedlallemruS(us

8. FaseJculuscunealus 9. Nucleus of spinal lracl of 9. Spinothillamiclraet

9. Nucleus groJcllr.; lrlgemlnal (V) nerve 10.

10. Fasckulus9facilis 10. lateral wstlbular nucleus 11. SuperlOfcolliculus

11. Central canal

11. Middle cerebellar peduncle

11.. Art:uatefibres

12. tv ventricle

Frances Yeung 2005

Figure 4. Spinothalamic Pain Pathway from Face

Figure 7. Brainstem

Toronto Noles 2008 Differential Diagnosis of Common Presentations Neurology N3

Differential Diagnosis of Common .

Presentations

1. Headache

migraine

tension-type

cluster

subarachnoid hemorrhage

meningitis

increased intracranial pressure

temporal arteritis

2. WeaknesslParalysislParesis/Loss of Motion

stroke

tumour

Parkinson's disease

Wilson's Disease

multiple sclerosis

myasthenia gravis

Guillain-Barre syndrome

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

peripheral neuropathies

myopathies

3. Sensory Complaints/Numbness/Paresthesia

stroke

tumour

multiple sclerosis

peripheral neuropathies

B12 deficiency

4. Facial Pain

sinusitis

dental disease

tic douloureux (Trigeminal Neuralgia)

trigeminal neuropathic pain (2 to trigeminal nerve injury or disease)

glossopharyngeal neuralgia

postherpetic neuralgia

atypical facial pain

MS

compression of trigeminal roots from tumours or aberrant vessels

5. Facial Weakness

upper motor neuron

TIA/stroke

post-ictal hemiparesis

tumour

infection: otitis media, mastoiditis, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes zoster

virus (HZV), Lyme disease, HIV

lower motor neuron

infection: otitis media, mastoiditis, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes zoster

virus (HZV), Lyme disease, HIV

idiopathic (Bell's palsy)

sarcoid

neuropathy (DM)

parotid gland

6. Altered Mental Status

drug toxicity/overdose (i.e. opioids, benzodiazepincs, alcohol etc.)

trauma

stroke

hypertensive encephalopathy

space occupying lesion (sub-arachnoid hemorrhage, subdural hematoma,

tumour, abscess, hydrocephalus)

post-ictal state

delirium (see Psychiatry. PSI?)

dementia (see Psychiatry. PSI8)

metabolic abnormalities (i.e. hepatic encephalopathy, uremia, electrolyte

disturbances, acid-base disturbances)

endocrine (i.e. hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis)

infectious (i.e. bacterial meningitis, viral encephalitis, abscess, empyema)

psychiatric disease (i.e. depression)

N4 Neurology Differential Diagnosis of Common Presentations Toronto Notes 2008

~

7. Acute Loss of Vision

central retinal artery occlusion (retinal infarct)

ophthalmologic (retinal detachment, glaucoma; see 0rhthalmology. OP27, OP30)

anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (arteritic/tempora arteritis or

nonarteritic/atherosclerosis)

TIA/amaurosis fugax

stroke (hemianopsia/quadrantanopsia)

pseudotumour cerebn (advanced stage)

8. Diplopia

cranial nerve III/IVNI Palsies (OM, tumour, trauma, aneurysm)

brainstem pathology (stroke, tumour, MS)

thyroid opnthalmopathy

cavernous sinus pathology

myasthenia gravis

Wernicke encephalopathy

loptomeningeaf disease (e.g. meningitis)

Gullain-Barre syndrome (e.g. Miller-Fisher Variant)

9. Ptosis

cranial nerve III palsy

myasthenia gravis (uni/bilateral)

Horner's syndrome

congenital/idiopathic

myotonic dystrophy (bilateral)

mitochondnal disease

10. Vertigo

brainstem lesions (stroke, MS)

cerebellar lesions

vertebrobasilar insufficiency

neurosyphilis

drugs/arcohol

peripheral causes (see Otolaryngology. OT6)

Review of Neurological Examination

Vitals: pulse (especially rhythm), BP, temperature

Head & Neck: look for meningismus, bruises/injuries/trauma to head (i.e. battle

sign/raccoon eyes) tongue biting may suggest seizures

CardiaclVascular: auscultate for bruits (e.g. carotid), murmurs

Neurological:

General Approach

1) State of Consciousness/Arousal

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Eye, Verbal, Motor)

reflexes: responses to pain may include decerebrate and decorticate posturing

see Altered Level of Consciousness, N7

2) Mental Status (see Psychiatry. PS2)

appearance, behaviour, mood, affect, speech, thought process, thought

content, perceptions, insight, judgement

assess as is appropriate throughout the interview

3) Cognition

Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE), clock drawing, Baycrest

Neurocognitive Assessment

frontal lobe testing for perseveration

4) Cranial Nerve Examination (see Table 2)

5) Motor Examination

inspection: bulk, accessory movements, tremor, fasciculations, etc.

tone (assess for rigidity, spasticity, clonus)

power (0-5, 0: no contraction, 1: flicker, 2: active movement with gravity

eliminated, 3: active movement against gravity, 4-,4, 4+: active

movement against gravity and resistance,S: full power)

reflexes (0 - 4+, 0: absent with reenforcement, 1+: reduced, 2+: normal,

3+: increased, 4+: clonus present)

6) Sensory Examination

posterior columns (vibration, proprioception, light touch)

spinothalamic (pain, temperature)

cortical sensation (graphesthesia, stereognosis, extinction, 2-point

discrimination)

7) Co-ordination

finger to nose, heel to shin, rapid alternating movements

8) Stance & Gait

Romberg, tandem gait

Toronto Notes 2008 Differential Diagnosis of Common Presentations Neurology N5

Lesion Localization (WHERE is the lesion?)

----........-_...

Table 1. Anatomic Approach to Neurological Disorders, Symptoms and Signs

Location of the lesion General Symptoms Common Disorders

Cortex & Contralateral sensory & motor deficits Seizure disorder (cortex only)

Intemal capsula Cortical lesions: associated with aphasia, neglect, extinction, Coma

agraphaesthesia, astereognosia, visual loss Stroke

(higher level dysfunctions)

Internal capsule lesions: associated with pure motor, pure

sensory losses, incoordination, absence of cortical features

Cerebellum & Incoordination Cerebellar degeneration

Basal ganglia ~ Abnormal intentional movements for Parkinson's disease

cerebellar lesions (ipsilaterall Stroke

~ tremor, bradykinesia, involuntary movements for

basal ganglia lesions

Brainstam (unilatarall Contralateral UMN paralysis, contralateral proprioceptive Cranial nerve palsies

(midbrain CN 3-4; and pain temperature loss below the head and ipsilateral Stroke

pons CN 6-7; CN defects. CN defects and sensory/motor deficits are on

medulla CN 8-10) opposite sides in brain stem lesions - "crossed-signs"

MIDBRAIN: diplopia, ptosis, unreactive pupil

PONS: LMN facial weakness, quadriparesis in bilateral pontine

lesions, pinpoint pupils

MEDULLA: lateral or medial medullary syndromes

Spinal cord (unilateral) Ipsilateral paralysis and proprioceptive loss, contralateral Spinal cord syndromes

pain-temperature loss below the level of the lesion -

"crossed-signs"

Sensory level, bowellbladder dysfunction

paraparesis

Brown-Sequard syndrome

Nerve root Radicular pain +sensory/motor deficits Nerve root compression

or absent reflex Disk herniation

Paripheral nerve Ipsilateral motor and sensory deficits along Neuropathies

a nerve distribution. Presence of LMN signs

Neuromuscular junction Proximal & symmetrical muscle weakness without Myasthenia gravis

sensory loss, fatigability or fasciculations Lambert-Eaton syndrome

Diplopia, ptosis, bulbar weakness Botulism

Muscle Proximal & symmetrical muscle weakness without Muscular dystrophies

sensory loss Myopathies including polymyositis

Dermatomyositis

Table 2. Some helpful findings on physical examination

Cranial Nerves

CN1 Unilateral loss of smell suggests frontal lobe lesion (avoid irritative stimuli which stimulate CN51

CN2 Look at optic discs for edema and optic atrophy

CN3'4i6 Look for pupillary abnormalities, ptosis, abnormal eye movements

Drug reactions:

bilaterally dilated fixed pupils with anticholinergics le.g. atropine, 'mushrooms'). but also seen in herniation

bilaterally small fixed pupils with morphine and related drugs, but also seen in pontine lesion

Horner's syndrome: ptosis, miosis (anisocoria), anhydrosis Idue to interrupted sympathetic nerve supplyl

CN3 palsy: ptosis, eye is down and out, +/- impaired pupillary response (suggests astructural/compressive cause)

CNS Absent corneal reflex may be CN5 (sensory deficit) or CN7(motor deficit)

CN7 Forehead sparing: upper motor neuron lesion

CN9'10 Dysarthria

Motor System

Ataxia may be due to cerebellar disease, proprioceptive abnormality

Ataxia with eyes closed only is apositive Romberg's sign suggesting aloss of joint position sense/peripheal neuropathy

Ataxia with eyes open or closed suggests cerebellar disease

Pronator drift suggests hemiparesis or loss of position sense

Spasticity indicates upper motor neuron disease

Atrophy and fasciculations indicates lower motor neuron disease

Cogwheel rigidity is seen in extrapyramidal processes le.g. Parkinson's Diseasel

Symmetrical weakness of proximal muscles suggests myopathy; of distal muscles suggests polyneuropathy

Sensory System

Hemisensory loss with sensory level or dissociation loss suggests spinal cord lesion

Symmetrical distal sensory loss suggests polyneuropathy

Loss of vibretion sense suggests peripheral neuropathy or posterior column lesion

Impaired graphesthesia and stereognosis with intact primary sensation indicates parietal lesion

Reflexes

Increased in upper motor neuron disease

Decreased/absent in lower motor neuron disease, myopathies or neuromuscular junction disorders

Slow relaxation of ankle reflex is seen in hypothyroidism ('hung reflexes')

Babinski sign suggests an upper motor neuron lesion but may be seen following aseizure

Other

"Doll's eye" movement, if absent, suggests pons or midbrain lesion or very deep coma

Loss of vestibulo-ocular reflex with caloric stimulation suggests brain stem lesion or drug toxicity

Absence seizures can be precipitated by hyperventilation

Characteristic skin lesions are seen in neurocutaneaous syndromes (e.g. neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis complex, Sturge-Weber

syndrome). non-blanching petechiae are seen in meningitis, ThromboticThrombocytopenic Purpura (TIP)

N6 Neurology Diagnostic Investigations Toronto Notes 2008

Diagnostic Investigations

Lumbar Puncture

Indications

suspected meningitis, sub-arachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (CT negative), encephalitis,

CNS neoplasm (lymphoma, meningeal spread), work up of demyelinating diseases

and CNS vasculitis, mtrathecal drug injection

Contraindications

increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

must do cr first to rule out increased intracranial pressure (ICP)

do not attempt if mass lesion associated with papilledema, decreased level of

consciousness (LOC), or focal neurolOgical defiClt

coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, anticoagulation

infection over lumbar puncture (LP) site

uncooperative patient

Complications

immediate: tonsillar herniation

delayed

post-LP headache (20-25%) - worse when upright, better supine

management: keep patient supine, po fluids, analgesia, blood patch

spinal epidural hematoma

infection

Table 3. Lumbar Puncture Interpretation

Condition Colour Protein Glucose Cells Other

Infectious

Viral infection Clear or opalescent Normal <0.45-1 gil Normal <100Oxl1J6/L

or slightly increased >3.0 mmoVL Lymphocytes mostly,

some PMNs

Bacterial infection Opalescent yellow, may clot >1 giL Decreased >100OxllJ6/L PMNs

(usually <2.0 mmoVL)

Granulomatous infection Clear or opalescent Increased but usually <5 giL Decreased lusually <1000xllJ6/L

(tuberculosis, fungal) <2.Q.4.0 mmol/LI Lymphocytes Low CSF glucose in TB

Neurologic

GuillainBarre Syndrome Clear or cloudy Markedly increased Normal Normal

Mulliple Sclerosis Clear Normal or increased Normal o-20x11J6/L lymphocytes Oligoclonal banding

Pseudotumour Cerebri Clear Normal Normal Normal Elevated opening pressure

Other

Neoplasm Clear or xanthochromic Normal or increased Normal or decreased Normal or increased Cytology pcsitive

lymphocytes

Traumatic tap Bloody, no xanthochromia Normal Slightly increased RBCs =peripheral blood,

less RBCs in tube 4than tube 1

Subarachnoid hemorrage Bloody, or xanthochromia Increased Normal WBClRBC ratio same as blood

after 28 h

What to send LP for

Tube #1: Cell Count and Differential

RBCs

WBCs and differential (normal: <3.0 x 106/L)

bacterial: predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs)

viral: predominantly lymphocytes

xanthochromia (yellow in colour)

supernatant should be clear; if yellow, implies recent bleed into

cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

traumatic tap does not give xanthochromia

Tube #2: Chemistry

glucose

must compare to simultaneously drawn serum glucose

bacterial: < 2.0 mmol/L or < 25% serum glucose

viral: CSF glucose is approximately 60% serum glucose ( >3.0 mmol/L)

protein

normal: <450 mgfL

bacterial: >1000 mg/L

viral: <1000 mgfL

albuminocytological dissociation: increased protein with normal cell

count implies Guillan-Barre syndrome (GBS)

additional tests: protein electrophoresis showing oligoclonal banding

may signify multiple sclerosis (MS)

CSF IgG: increased in MS and demyelinating neuropathies

Toronto Notes 2008 Diagnostic Investigations!Altered Level of Consciousness Neurology N7

Tube #3: Microbiology

gram stain

C&S

specific tests depending on clinical situation/suspicion

viral: PCR for herpes simplex virus (HSV)

bacterial: polysaccharide antigens of HJlu, N.meningitides,

Pneumococcus

fungal: Cryptococcal antigen, India ink stain (cryptococcus), culture

TB: Acid-Past stain, TB culture, TB PCR

Tube #4: Cytology (for evidence of malignancy)

Tube 1/5: RBCs (cell count) - similar to tube 111

if RBCs in tube #1 is RBCs in tube #5 then consider traumatic tap

in SAH, RBCs in tubes #1 and #5 should be approximately equal

Altered Level of Consciousness

see Neurosurgery, NS29

~ ~ _ ~ _ . ~ __...... ..,......l

Evaluation of Patient

History

previous/recent head injury (hematomas)

sudden collapse (ICH, SAH)

cardiovascular surgery, prolonged cardiac arrest (hypoxia)

limb twitching, incontinence, tongue biting (seizures, post-ictal state)

recent infection (meningitis)

other medical problems (diabetes mellitus (DM), renal failure, hepatic encephalopathy)

psychiatric illness (drug overdose)

telephone witnesses, read ambulance report, check for medic-alert bracelet

neurologic symptoms (headache, visual changes, focal weakness)

Physical Examination

Glascow Coma Scale

pupils - reactivity and symmetry, papilledema (increased ICP)

reflexes

corneal reflex: Normal =bilateral blinking response

gag reflex: Normal = gag

oculocephalic reflex (doll's eye): Normal = eyes move in opposite direction of

head, as if trying to maintain fixation of a point

vestibulocochlear response (cold caloric): Normal =nystagmus fast phase away

from stimulated ear

deep tendon reflexes

plantar reflex: Normal = flexor plantar response

tone

spontaneous involuntary movements

assess for meningeal irritation, increased temperature

assess for head injury, battle sign, racoon eyes, skin rashes, and joint abnormalities

that may suggest vasculitis

Coma

Definition

a state in which patients show no meaningful response to environmental stimuli, from

which they cannot be roused; umousable unresponsiveness

Pathophysiology

coma can be caused by lesions affecting the cerebral cortex bilaterally, the reticular

activating system (RAS) or their connecting fibres

focal supratentorial lesions do not alter consciousness except by herniation (with

compression on the brainstem or on the contralateral hemisphere) or by precipitating

seizures

Classification

structural lesions (tumor, pus, blood, infarction, CSF); 1/3 of comas

supratentorial mass lesion - leading to herniation as outlined above

infratentorial lesion - compression oT or direct damage to the RAS or its projections

..... ,,

~ ~ - - - - - - - - - - ,

~ r - - - - - - - - - - - - - ,

Glasgow Coma Scale

Eyes Open

Spontaneously 4

To voice 3

To pain 2

No response 1

Best Verbal Response

Answers questions appropriately 5

Confused, disoriented 4

Inappropriate words 3

Incomprehensible sounds 2

No verbal response 1

Best Motor Response

Obeys commands 6

Localizes to pain 5

Withdraws from pain 4

Decorticate (flexion) 3

Decerebrate (extensionI 2

No response 1

..... ' ,

Caloric Reflexes COWS

Cold Opposite, Warm Same

N8 Neurology Altered Level of Consciousness/Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy Toronto Notes 2008

metabolic disorders/diffuse hemispheric damage; 2/3 of comas

deficiency of essential substrates (e.g. oxygen, glucose, vitamin B12)

exogenous toxins (e.g. drugs, heavy metals, solvents)

endogenous toxins/systemic metabolic diseases (e.g. uremia, hepatic

encephalopathy, electrolyte imbalances, thyroid storm)

infections (meningitis, encephalitis)

trauma (concussion, diffuse shear axonal damage)

Investigations and Management

ABCs

labs: electrolytes, TSH, LFTs, Cr, BUN, Ca, Mg, PO<v tox. screen, glucose

CT/MRI, LP, EEG

consult neurosurgery if required

Persistent Vegetative State

Definition

a condition of complete unawareness of the self and the environment accompanied by

sleep-wake cycles with either complete or partial preservation of hypothalamic and brain

stem autonomic function

'awake but not aware'

follows comatose state

EtiologylPrognosis

most commonly caused by cardiac arrest or head injury

due to irreversible loss of cerebral cortical function BUT with intact brainstem function

average life expectancy 2-5 years

Brain Death

see also Neurosurgery. NS32

Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy

Seizure

Definition

seizure = paroxysmal alteration of behaviour and/or EEG changes that results from

abnormal, excessive activity of neurons

epilepsy = condition characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizure activity

ictal =seizure

post-ictal = state of confusion/somnolence that can occur after some seizure types

inter-ictal = epileptic discharges that can be seen on EEG occuring between seizures

Classification

Table 4. Classification of Seizures

Partial (focal) seizures Generalized seizures

Simple partial seizures (without altered LOC) Absence Atonic

with motor signs typical Unclassified

with somatosensory or special sensory signs atypical

with autonomic signs Clonic

with psychic symptoms Myoclonic

Complex partial seizures (with altered LOCI 'Tonic

Partial seizure evolving to a 2' generalized seizure 'Tonic-c1onic

Etiology

Generalized

infectiolls/inllammatory

encephalitis, meningitis, neurocystercercosis

toxic/traumatic

medications (tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), monoamine oxidase

inhibitors (MAOls), neuroleptics, cyclosporine, theophylline, isoniazid)

drugs (alcohol withdrawal, cocaine, amphetamines)

Toronto Notes 2008 Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy Neurology N9

anatomic

diffuse cerebral damage (anoxia, storage diseases)

metabolic

hypoxia

electrolytes (hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, hypernatremia,

hyperosmolality)

end-stage organ failure (renal, hepatic)

other (e.g. porphyria)

neonatal causes

idiopathic

epilepsy

Partial (focal)

vascular

cerebral hemorrhage, cortical infarcts, arteriovenous malformations

(AVMs), cavernous malformations, subdural hematoma

infectious/inflammatory

meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral abscess, subdural empyema, syphilis,

tuberculosis (1'8), HIV

sarcoidosis, systemic lUpus erythematosus (SLE)

toxic/trauma

cerebral trauma (subdural hematoma)

anatomic

hippocampal sclerosis

cortical dysplasias

neoplastic

primary or metastatic CNS tumours

neonatal

birth injury (e.g. hypoxia), IVH

idiopathic

epilepsy

Epidemiology

in developed countries, 2% to 4% of all persons have recurrent seizures at some period

in their lives; higher incidence in developing countries (i.e. cysticercosis is one of the

most common causes)

incidence highest among young children and elderly

age of onset: primary generalized seizures rarely begin <3 or >20 years of age

M:P = 1.5:1

epilepsy affects about 45 million people worldwide

Risk Factors

stroke risk factors (see Stroke, N57)

past history of neurological insult: birth injury, head trauma, stroke, CNS infection,

drug use/abuse

past history of seizures

family history of seizures

malignancy

Precipitants

sleep deprivation, drugs/alcohol, TV screen, strobe, emotional upset

fever: febrile seizures affect 4% of children between 3 months - 5 years of age;

benign if brief, solitary, generalized tonic-clonic seizure lasting less than 15 minutes

and not more frequent than once/24 hours (see Pediatrics. P80)

Signs and Symptoms (Table 5, Table 6)

during seizure

unresponsiveness or impaired LOC

nature of neurological features suggests location of focus

motor =frontal lobe

visual/olfactory/gustatory hallucinations = temporal lobe

salivation, cyanosis, tongue biting, incontinence, loud cry

Jacksonian march: one body part is initially affected, followed by spread to

other areas (e.g. fingers to hand to arm to face)

adversive: head or eyes are turned forcibly to the contralateral frontal eye field

automatisms: patterns of repetitive activities that look purposeful

(e.g. chewing, walking, lip-smacking)

temporal lobe epilepsy: behavioural disturbances, automatisms, olfactory or

gustatory hallucinations

1

9

'

Stroke is the most common cause of

lateonset (>50 years of agel epilepsy,

accounting for 5080% of cases.

NIO Neurology Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy Toronto Notes 2008

.... '

..

I

Motor andlor sensory partial

seizures indicate structural disease

until proven otherwise.

duration: ictus is seconds to minutes, post-ictus can be long

(minutes to hours)

after seizure

post-ictal symptoms: limb pains, tongue soreness, headache, drowsiness,

Todd's paralysis (paresis)

Table 5. Partial Seizures

Simple motor arise in precentral gyrus Imotor cortex!. affecting contralateral faceJtrunkJ1imbs

ictus

no dlange in consciousness

rhythmical jerking or sustained spasm of affected parts

dlaracterized by forceful turning of eyes and head to side opposite the discharging focus ladversive seizures)

may start in one part and spread "uP/down the cortex'IJad<sonian mardl- remember the homunculus)

duration usually seconds to minutes !Todd's may last hoursl

arise in sensory cortex (postcentral gyrus), affecting contralateral faceJtrunkilimbs

Simple sensory somatosensory

numbnessltinglingl"electric" sensation of affected parts

a"mardl' may occur

other forms include: visual, auditory, gustatory, vertiginous (may resemble schizophrenic hallucinations but patient

recognize the unreality of phenomena)

Simple autonomic epigastric disconfort, pallor, sweating, flushing, piloerection, and pupillary dilatation

Simple psychic disturbance of higher cerebral function

symptoms rarely occur without impairment of consciousness and are mudl more commonly experienced as complex partial

seizures

Complex partial seizures causing aherations of mood, memory, perception

lternporallobe epilepsy, common form of epilepsy, with increased incidence in adolescents, young aduhs

psychomotor epilepsy)

ictus

automatisms occur in 90% of patients Idlewing, swallowing, lipsmacking, scratdling, fumbling, running, disrobing,

continuing any complex act initiated prior to loss of consciousness)

aura of secondsminutes

forms include:

dysphasic, dysmnesic (deja vU), cognitive Idreamy states, distortions of time sense),

affective Ilear, anger), illusions (macropsia or micropsia), structured hallucinations Imusic, soenes, taste, smells),

epigastric fullness

then patient appears distant, staring, unresponsive (can be brief and confused with absence seizuresl

recovery is dlaracterized by confusion headadle

can resemble schizophrenia, psydlotic depression lif complex partial statusl

Table 6. Generalized Seizures

Absence onset in dlildhood

(Petit Mal) hereditary

autosomal dominant

incomplete penetrance 1-1/4 will get seizures, -113 will have dlaracteristic EEG findings)

3Hz spike and slow-wave ectivity on EEG

ictus

, dlild will stop activity, stare, blink/roll eyes, be unresponsive; lasting approximately 5-10 seconds or so, but may occur

hundreds of times/day

may be induced by hyperventilation

often associated with poor sdlolastic pertormance

Myoclonic ictus

sudden, brief, generalized muscle contractions lrapid jerking movementsl

most common disorder is juvenile myoclonic epilepsy lonset after puberty, does not remit with agel

also occurs in degenerative and metabolic disease le.g. hypoxic encephalopathyl

Toni:lonic common

(Grand Mal) all of the classic features do not necessarily occur every time

prodrome of unease, irritability hourso{jays before attack

ictus

aura lif secondarily from apartial onset) seconds to minutes before attack of olfactory hallucinations, epigastric

discomfort, deja vu, jerking of alimb, etc.

tonic phase: tonic contraction of muscles, with arms flexed and adducted, legs extended, respiratory muscles in spasm ("cry'

as air expelledl, cyanosis, pupillary dilatation, loss of consciousness, patient often "thrown' to the ground; lasting 10-30 seconds

clonic phase: clonus involving violent jerking of face and limbs, tongue biting, and incontinence; duration variable

postictal phase of decreased level of consciousness, with flaccid limbs and jaw, extensor plantar reflexes, loss of comeal reflexes; lasts

hours; headadle, confusion, adling muscles, sore tongue, amnesia; serum CK elevated for hours

Investigations

CBC, sodium, glucose, Ca, Mg, Cr, BUN, LFTs

CXR, ECG

EEG (bursts of sharp and slow waves represent epileptiform activity; focal epileptiform

in secondarily generalized; spikes and slow waves at 3Hz in absence) - interictal EEG is

normal in 60% of cases

prolactin-increased post-ictally with generalized tonic-clonic seizure (compare with

baseline level)

CT/MRI except for definite primary generalized epilepsy

LP if signs of infection and no papilledema or midline shift of brain structures

(generally done after CT or MRI, unless suspicious of meningitis)

tox screen

Toronto Notes 200S Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy Neurology Nll

Differential Diagnosis

syncope (see Table 7)

note: syncope may induce a seizure - this is not epilepsy

pseudoseizure (see Table 8)

anxiety: hyperventilation, panic disorder

TIA

hypoglycemia

movement disorders: myoclonus, episodic ataxias

alcoholic blackouts

migraine: confusional, vertebrobasilar

narcolepsy (cataplexy)

Table 7. Seizures versus Syncope

Characteristic Seizura Syncope

Time of onset day or night day

Position

any

upright, not recumbent

Onset sudden or brief graduallvasodepressorl

Aura possible specific aura diuiness, visual blurring, lightheadedness

COlour normal or cyanotic (tonic-elonicl pallor

Autonomic features uncommon outside of ictus common

diaphoresis

Duration brief or prolonged brief

Urinary incontinence common rare

Post-ictal symptoms can occur with tonic-clonic or complex partial' rare

Motor activity can occur occasional brief jerks

Injury common, tongue biting rare, from fall

Automatisms can occur with absence or complex partial none

EEG frequently normal, but may be abnormal normal

Table 8. Seizures versus Pseudoseizures (non-epileptic "seizures"'conversion disorder)

Characteristic Epileptic Seizure Psaudoseizure

Age any any, less common in elderly

M=F F>M

Triggers uncommon emotional disturbances

Duration brief may be prolonged

Motor activity automatisms in complex partial seizures opisthotonos

stereotypic rigidity

synchronous movements forced eye closure

irregular extremity movements

side-to-side head movements

pelvic thrusting

crying

Timing day or night usually day

usually other people present

Physical injury may occur non-serious

Urinary incontinence may occur

rare

Reproduction of attack spontaneous suggestion, or stimuli plus suggestion

EEG inter-ictal discharges frequent normal

Prolactin increased normal

Treatment

psychosocial

educate patients and family

advise about swimming, boating, locked bathrooms, operating dangerous

machinery, climbing heights, chewing gum

pregnancy issues: counselling and monitoring blood levels closely,

teratogenicity of anticonvulsant drugs, folate 4-6 mg/day (throughout

child-bearing years), vitamin K (at time of delivery)

evaluate for fetal neural tube defects

inform of prohibition to drive and requirements to notify Ministry of

Transportation

support groups, Epilepsy Association

follow-up visits to ensure compliance, evaluate changes in symptoms/seizure

type (re-investigate)

N12 Neurology Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy Toronto Notes 2008

o

pharmacologic (Table 9)

begin with one major anticonvulsant with a simple dosage schedule

adjust dose to achieve plasma level in therapeutic range

if no seizure control, increase dose until maximum safe dose or side effects

become intolerable

if still no seizure control, change to or add second drug

non-pharmacologic treatment

for selected cases of complex partial epilepsy and/or identifiable focus

vagal nerve stimulator

ketogenic diet

surgical resection

Table 9. Major AntiEpileptic Drugs

Type of Seizure Medication Dosing Schedule Therapeutic ranges

Partial or carbamazepine carbamazepine: start at 100-200 mg PO OD-bid, increase by 17-50 umoVL

2' generalized phenytoin 200mgld q2d up to 800-1200 mg/d lin divided dosesl if needed

valproate (mechanism. antkonvulsant, voltage dep. block of Na channelsl

phenytoin: if loading necessary -300 mg PO q4h x3doses, 40-80 umol/L

l' generalized valproate then 300 mg PO hs. Serum levels should be monitored if giiven IV do not exceed

lTonic-Clonicl phenytoin (mechanism voltage dependant block of Na channelsl 50 mglmin

(Grand Mall carbamazepine

va/praate. start at 15 mgt1<g/d PO increasing by 5-10 mgt1<g1d qweekly 350-700 umoVL

until seizures are controlled or intolerable side effects. Maximum daily

dose is 60 mgt1<g/d Imechanism unknown; GABA enhancingl

Absence ethosuximide ethosuximide: start 500 mg daily PO in divided doses, increasing by 280-710 umoVL

IPetitMal1 valproate 250 mgld q4-7days pm up to amaximum dose of 1500 mgld

Imechanism: inhibits NADPH-linked aldehyde reductase necessary

for the formation of GABAI

Myoclonic clonazepam clonazepam: 0.5 mg PO tid, increase by 0.5-tO mg/d q3d pm

valproate up to 20 mgld (in divided doses)

(mechanism: benzodiazepine; GABA enhancerl

Source: Clinician's Pocket reference 9lb Gomella LG &Haist SA Eds, McGraw-Hili, NewYork, 2002.

Pharmacological Treatment of Diseases, Pressaco J &Yu HEds, Urban Angel Medical Books, Toronto, 1996.

other adjuncts: clobazam, gabapentin, pregabalin

newer anticonvulsants: lamotrigine, topiramate, levetiracetam

Status Epilepticus

a life-threatening state (5-10% of epileptics) with either a continuous seizure lasting at

least 30 minutes or a series of seizures occurring without the patient regaining full

consciousness between attacks

complications: repetitive grand mal seizures impair ventilation, resulting in anoxia,

cerebral ischemia and cerebral edema; sustained muscle contraction can lead to

rhabdomyolysis and renal failure

Initial Management

ABCs

lateral semi-prone position, mandible pushed forward; use

oropharyngeal tube with high-flow oxygen

monitor vitals, including temperature

pulse oximetry

start intravenous lines

interrupt status (proceed through steps if seizure continues):

1. give 50 mL 50% glucoseN and thiamine 100 mg IM

2. [orazepam (0.1 mglkg IV at 2 mg/min)

3. ehenytoin (15 mglkg IV at maximum of 50 mg/min) or fosphenytoin

(20 mglkg PE IV at 150 mg/min), monitor cardiac rhythm and BP

4. additional phenytoin (5-10 mglkg IV at maximum of 50 mg/min can give up to a

total dose of phenytoin of 20 mg/kg) or fosphenytoin (5-10 mglkg PEN at 150 mg/min)

5. phenobarbita1 (20 mglkg IV at 50 mg/min); watch for hypotension and

respiratory depression (high dose IVbarbiturates requires central line to monitor

CVP)

6. if seizures continuing at this point, consider additional phenobarbital

(5-10 mg/kg IV at 50 mg/min) or proceed directly to 7

7. anesthesia with midaz01am or propofol (in ICU)

take focused history and examine patient

trauma

known seizure disorder

focal neurological signs

history or signs of medical illnesses, especially infection

check for neck stiffness, signs of head injury

Toronto Notes 2008 Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy/Behavioral Neurology Neurology N13

investigate cause of the status

CBC, electrolytes (including Ca), liver enzymes, Cr, BUN

glucose level (rule out hypoglycemia)

ABG

draw metabolic and drug screen (most common is alcohol)

measure anticonvulsant levels

CXR, EEG and consider STAT CT or MRI if first seizure or if focal neurological

deficits elicited

LP to evaluate for infection and subarachnoid hemorrhage if CT normal

Behavioural Neurology

see Psychiatry, PS17

Acute Confusional StatelDelirium

o

Table 10. Clinical Features of the Acute Confusional State

Level of consciousness " alertness, " attention, " concentration; fluctuating; worse at night. "sundowning" .... ' ,

.}--------------,

Psychomotor stetus psychomotor retardation

Delirium is characterized by acute

psychomotor agitation

onset, disorientation, marked vari-

Emotional status anxietyflrritability ability, altered level of conscious-

depression/apathy

ness, poor attention, and marked

psychomotor changes.

Perception illusions and hallucinations (usually visual and tactilel

gustatOly and olfactory hallucinations suggest temporal lobe epilepsy

Cognition memory disturbance (registration, retention, and recall)

disorientation

Table 11. Selected Intracranial Causes of Acute Confusion

Etiology Key Clinical Features Investigations

Vasculer Subarachnoid hemorrhage thunderclap headache CT (non-contrast)

'1' ICP 'LP

meningismus

StrokernA focal neurological signs CT (non-contrastl

Infectious Meningitis fever, headache, nausea, photophobia

LP

meningismus

Encephalitis focal neurological signs 'LP;MRI

fever, headache, t seizure

Abscess '1' ICP CT with contrast

focal neurological signs (often ring enhancing lesionI

Traumatic Diffuse axonal shear, trauma Hx CT Inon-eontrastl

Epidural hematoma, '1' ICP 'MRI

Subdural hematoma focal neurological signs

Autoimmune Acute CNS vasculitis skin rash, active joints ANA; ANCA; RF .... ' ,

) - - ~ = = = = - - - - - ,

MRI

angiography

Visual Hallucinations more com-

Neoplestic Mass effect/edema, '1' ICP CT (non-contrast)

monly indicate organic disease.

Hemorrhage, focal neurological signs 'MRI

Seizure papilledema

Seizure Status epilepticus see Seizure Disorders and Epilepsy, NB 'EEG

Todd's phenomenon

Primery psychiatric Psychotic disorder no organic signs or symptoms no specific tests

Mood disorder

Anxiety disorder

N14 Neurology Behavioral Neurology Toronto Notes 200S

Table 12. Selected Extracranial Causes of Acute Confusion - "HIT ME"

~ )

Etiology Key Clinical Features Investigations

'

Hypoxia Respiratory failure cyanosis, tacl1ypnea, tacl1ycardia 'ABG;CXR

Etiology of Delirium

Heart failure '5&50fCHF ABG; CXR; ECG

Carbon monoxide ICO) Hx CO exposure 'ABG

Infectious

poisoning

Withdrawal from drugs

Infectious Septicemia systemic S&S septicemia blood C&S

Acute metabolic disorder Pneumonia cough; respiratory distress 'CXR

Trauma UTI irritative urinary S&S urine R&MlC&S

eNS pathology

Hypoxia

ToxinSiMeds Alcohol see Emergency Medicine, ERSt toxicology screen

Benzodiazepines drug levels

Betablockers

Deficiencies in vitamins

Anticl10linergics

Endocrinopathies

Acute vascular insults

Metabolic Hepaticlrenal failure 5&S acute hepatic/renal failure liver enzymes; LFTs

Toxins see Gastroenterology, G32 , Nephrology, NP29 electrolytes, BUN, Cr

Heavy metals Electrolyte imbalance ' s e e ~ N P 9 electrolytes

'Ca panel

B" deficiency peripheral neuropathy; subacute combined serum 8

12

degeneration; glossitis 'CBC

Endocrine 1'/01- thyroid S&S hyper/hypothyroidism 'T5H,T3,T4

1'/01- glucose S&S DMihypoglycemia serum glucose

1'/01- cortisol S&S Cushing'siAddison's disease serum cortisol

Management of Acute Confusion - General Measures

well-lit room

hearing aids and glasses

orienting stimuli (clocks, calendars)

avoid restraints or catheters

stop all unnecessary medications

treat underlying cause, antipsycotics

~ Dementia

See Psychiatry, PS18

Definition

an acquired, generalized and (usually) progressive impairment of cognitive

function (i.e. memory, recall, orientation, language, abstraction etc.)

affects content, but not level of consciousness

affects 5-20"10 of people over age 65

Epidemiology

15"10 of those> 65 years of age have dementia

common etiologies: 60-80"10 Alzheimer's Disease (AD); 10-20"10 vascular dementia

<5"10 reversible: hypothyroid, normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH), nutritional

deficiencies, depression and infection

History

'll' geriatric giants

incontinence/falls/polypharmacy

ADI.s IDEATH) IADLs ISHAFT) memory and safety (wandering, leaving doors unlocked, leaving stove on,

Dressing Shopping losing objects)

Eating Housekeeping behavioural (mood, anxiety, psychosis, suicidal ideation, personality

Ambulating Accounting changes, aggression)

Toileting Food preparation cardiovascular, endocrine, neoplastic

Hygiene Transportation EtOH, smoking

OTes, herbal remedies, compliance, accessibility

collateral history is usually very helpful

history of vascular disease

Physical Examination

hearing and vision

neurological exam

as directed depending on risk factors and history

MMSE

+ clock drawing

+ frontal lobe testing (go/no-go, word lists, similarities, proverb)

+ Baycrest NeurocognitiVE' Assessment

Toronto Notes 2008 Behavioral Neurology Neurology N15

Investigations

depend on suspected etiologies (see Tables 13 and 14)

CBC (note MCV), glucose, TSH, B12, folate

electrolytes LFTs renal function

CT head if Hx of TIA, stroke, focal neurological deficit, <65 years old,

rapid progression (weeks to months), immunocompromised, Hx of

neoplasm that can metastasize to brain, anticoagulant use

MRI as indicated

as clinically indicated - VDRL, HlV, ANA, anti-dsDNA, ANCA,

ceruloplasmin, copper, cortisol, toxicology, heavy metals

issues to consider

failure to cope

fitness to dnve

caregiver education and stress

respite services and day programs

power of attorney

wills

advanced directives (DNR)

Table 13. Common Causes of Dementia

Etiology Key Clinical Features Investigations

Primary degeneratiue Alzheimer's disease memory impairment CT or MRI, SPECT

aphasia, apraxia, agnosia

Lewy body disease hallucinations CT or MRI, SPECT

parkinsonism

fluctuating cognition

frontotemporal dementia disinhibition 'MRI, SPECT

(e.g. Pick's diseasel wsocial awareness

wpersonal hygiene

memory relatively spared

Huntington's disease chorea molecular testing

Vascular multi-infarct dementia abrupt onset MRI, SPECT

stepwise deterioration

systemic vasculopathy

CNS vasculitis systemic S&S of vasculitis ANA; ANCA; RF

'MRI

angiography

Table 14. Acquired Causes of Dementia

Etiology Key Clinical Features Investigations

Infectious chronic meningitis fever; headache; nausea LP +investigations

meningismus

localizing neuro deficits

chronic encephalitis fever; headache 'LP; MRI

chronic abscess '1' ICP CT with contrast

localizing neuro signs

HIV see Infectious Disease ID28 HIV serology

Creutzfelt-Jacob disease rapidly progressive 'EEG

syphilis ataxia, myoclonus

LP

'VDRL

Traumatic diffuse axonal shear, trauma Hx CT (non-contrast)

epidural hematoma, '1' ICP, papilledema

subdural hematoma localizing neuro signs

Rheumatologic SLE see RH9 MRI; ANA, anti-dsDNA

Neoplastic mass effect/edema, '1' ICP CT with contrast

hemorrhage, localizing neuro signs 'MRI

seizure

paraneoplastic encephalitis systemic S&S of cancer anti-Hu antibodies

Table 15. Reversible Causes of Dementia

Etiology Key Clinical Features Investigations

ToxinsIMeds Wernicke-Korsakoff anterograde amnesia no specific test

confabulation trial of thiamine

ataxia, ophthalmoplegia

benzodiazepines, see Emergencv Medicine, ER51 toxicology screen

Il-blockers, drug levels

anticholinergics

heavy metals S&S heavy metal toxicity urine heavy metals

Metabolic hepatidrenal failure S&S acute hepatidrenal failure liver enzymes; LFT's

see Gastroenterology. G32, Nephrology, NP29 electrolytes, 8UN, Cr

Wilson's disease KayserFleischer rings serum ceruloplasmin, Cu

hepatic failure

8" deficiency peripheral neuropathy; subacute combined serum Bl2

degeneration; glossitis

Endocrine 1'/,), thyroid S&S hyper/hypothyroidism 'TSH,T

3

,T,

1'/,), glucose S&S DMlhypoglycemia serum glucose

1'/,), cortisol S&S Cushing'siAddison's disease serum cortisol

Structural NPH gait apraxia 'CT

inconlinence

LP

dementia measure opening pressure

Primary Psychiatric depression (pseudodementia) no organic S&S no specific tests

N16 Neurology Behavioral Neurology Toronto Notes 2008

Alzheimer's Disease

Definition

progressive cognitive decline interfering with social and occupational functioning

characterized by the following

1) anterograde amnesia - impaired ability to learn new information

2) one of the following cognitive disturbance

a. Aphasia - language disturbance

b. Apraxia - impaired ability to carry out motor activities despite intact motor

function

c. Agnosia - failure to recognize or identify objects despite intact sensory function

d. Disturbance in executive function - planning, organizing, sequencing,

abstracting

Pathophysiology

genetic factors

a minority 7%) of AD cases are familial, autosomal dominant

3 major genes for autosomal dominant AD have been identified:

amyloid precursor protein (chromosome 21)

presenilin 1 (chromosome 14)

presenilin 2 (chromosome 1)

the E4 polymorphism of apolipoprotein E is a susceptibility genotype

pathology (although not necessarily specific for AD)

gross pathology

diffuse cortical atrophy, especially frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes

microscopic pathology

senile plaques (amyloid made from derived from cleaved

amyloid precursor protein)

neurofibrillary tangles (intracytoplasmic paired helical filaments with

and hyperphosphorylated Tau protein)

biochemical pathology

50-90% reduction in action of choline acetyltransferase

Epidemiology

1/12 of population 65-75 years of age

1/3 of population >85 years of age

accounts for 60-80% of all dementias

Risk Factors

FHxofAD

head injury

low education level

smoking

aluminum

Downs syndrome

Signs and Symptoms

cognitive impairment

memory impairment for newly acquired information (early)

memory impairment for remote events

deficits in language, abstract reasoning, and executive function

psychiatric manifestations

major depression (5-8%)

psychosis (20%)

motor manifestations (late)

parkinsonism (consider Lewy body disease)

Investigations

perform investigations to rule out other causes of dementia as necessary

EEG: generalized slowing (nonspecific)

MRI: dilatation of lateral ventricles; widening of cortical sulci, small infarcts (amyloid

angiopathy) nonspecific changes

SPECT: hypometabolism in temporal and parietal lobes

Treatment

acetylcholinesterase inhibitors have been shown to improve cognitive function

donepezil (Aricept)

rivastigrnine (ExelonTM)

galantamine (ReminyJTM)

other - although efficacy not proven

ginkgo biloba

tacrine

Toronto Notes 2008 Behavioral Neurology Neurology N17

Vit E

NMDA receptor agonist - memantine (Ebixa)

symptomatic management

low dose neuroleptic

trazodone for sleep disturbance

antidepressants

Prognosis

progressive

mean duration of disease 10 years

Lewy Body Disease (LBO)

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ~ - - - - -

Definition

progressive cognitive decline interfering with social or occupational function; memory

loss mayor may not be an early feature

one (for possible LBO) or two (for probable LBO) of the following:

fluctuating cognition with pronounced variation in attention and alertness

recurrent visual hallucinations

parkinsonism

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Lewy bodies (eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions) found in both cortical and

subcortical structures

Epidemiology

15-25% of all dementias

Signs and Symptoms

fluctuation in cognition with progressive decline

visual hallucinations

parkinsonism

repeated falls

sensitivity to neuroleptic medications (develop rigidity, neuroleptic malignant

syndrome, and extrapyramidal symptoms)

REM sleep disorder

Treatment

acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (e.g. donepezil)

Prognosis

typical survival 3-6 years

Frontotem oral Dementia

Definition

progressive dementia characterized by personality change, speech disturbance,

inattentiveness, and extrapyramidal signs

Etiology and Pathogenesis

gross pathology

atrophy of frontal and temporal poles

microscopic pathology

Pick bodies (intraneuronal inclusions containing abnormal Tau proteins)

Epidemiology

10% of all dementias

Signs and Symptoms

core features

insidious onset and gradual progression

early decline in social interpersonal conduct

early impairment in regulation of personal conduct

early emotional blunting

early loss of insight

behavioural disorder

decline in personal hygiene and grooming

mental rigidity/inflexibility

perseverative and stereotyped behaviour

speech and language

altered speech output (economy or pressure of speech)

echolalia/perseveration

N18 Neurology Behavioral Neurology Toronto Notes 2008

physical signs

primitive retlexes (i.e. pout, grasp, palmo-mental, glabellar)

parkinsonism

Investigations

MRljSPECT - frontotemporal atrophy/hypometabolism

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

------------'

see Neurosurgery. NS7

Definition

an acquired disturbance of language characterized by errors in speech production,

writing, comprehension, or reading

Neuroanatomy of Aphasia

Broca's area (posterior inferior frontal lobe) involved in speech production (expressive)

Wernicke's area (posterior superior temporal lobe) used for comprehension of

language

angular gyrus is responsible for relaying written visual stimuli to Wernicke's area for

reading comprehension

the arcuate fasciculus association bundle connects Wernicke's and Broca's areas

>99% of right-handed people have left hemisphere language representation

70% of left-handed people have left hemisphere language representation, 15% have

right hemisphere representation, and 15% have bilateral representation

Assessment of Language

.... ' , assessment of context

,,}-------------,

handedness (writing, drawing, toothbrush, scissors)

Aphasia localizes the lesion to the

education level

dominant cerebral hemisphere.

native language

learning difficulties

assessment for aphasia

1. spontaneous speech

fluency

\',

paraphasias: semantic ("chair" for "table"), or phonemic ("dable" for "table")

The left hemisphere is dominant for

2. repetition

3. naming

language in almost all right-handed

4. comprehension (auditory and reading)

people and 70% of left-handed people.

5. writing

6. neologisms

Approach to Aphasias

Table 16. Fluent Aphasias

Wernicke's Conduction Anomie SensoryTranscortical-

Lesion - posterior superior - arcuate fasciculus - numerous possible locations 1. subcortical temporoparietal

temporal lobe 2. temporoparietal watershed

11s1 temporal gyrus) between MCA and PCA

territories

Comprehension - poor 'good -good poor

Repetition - poor poor good

- good

Naming - relatively spared poor - poor - relatively spared

'Transcortical aphaSias are typically associated with cerebral anoxia (e.g. post-MI, CO poisoning, hypotension)

Table 17. Non-fluent Aphasias

Broca's Global MotorTranscortical' MixadTranscortical'

Lesion posterior inferior frontal lobe posterior inferior frontal lobe AND a. frontal lobe watershed between oombined sensory and motor

posterior superior temporal lobe MCA and ACA tenitories transoortical

b. white matter lesions deep to lal

Compt'ehension 'good poor 'good 'poor

Repetition poor poor 'good good

Naming poor 'poor poor poor

'Transcortical aphasias associated with cerebral anoxia le.g. post-MI, CO poisoning, hypotensionl

Toronto Notes 2008 Behavioral Neurology Neurology N19

Prognosis

most recovery from stroke-related aphasia occurs in first three months, but may

continue for>1 year

with recovery, the type of aphasia may evolve

poor prognosis: global aphasia

Dysarthria

Definition

inability to produce understandable speech due to impaired phonation (laryngeal

sound production) and/or resonance (the alteration of sounds in the cavity between

the larynx and the lips/nares) secondary to impaired motor control over peripheral

speech organs

Classification of Dysarthria

Table 18. Classification of Dysarthria

Classification Characteristics of Speech Etiologies'

Flaccid 'slurred, indistinct speech , motor neuron (e,g, ALSI

ILMN dysarthria or bulbar palsy) 'particular difficulty with vibratory "R"

'difficulty with lingual consonants produced by , peripheral nerve le,g, GBSI

tongue and labial consonants produced by lips , neuromuscular junction (e,g, MGI

, myopathy (e,g, dermatomyositis/polymyositis)

Spastic , slow and monotonous 'stroke

(upper motor neuron (UMN) dysarthria or 'strained or strangled 'tumour

pseudobulbar palsy) 'harsh , demyelination

, low pitched , degeneration

Ataxic , slow/akered rhythm 'cerebellar disease

improper stress , cerebellar outflow tract disease

, staccato speech

Extrapyramidal Hypokinetic , low-pitched , Parkinson's disease

, monotonous other causes of parkinsonism (see Movement

'decrescendo volume Disorders, N29)

Hyperkinetic Choreiform , Huntington's disease

, prolonged sentence segments , Dystonia musculorum deformans

intermixed with silences 'other hyperkinetic extrapyramidal disorders

'variable, improper stress (see Movement Disorders, N29)

'bursting quality

Dystonic

'slow speaking rate

'prolonged individual phonemes

'Abbreviations: ALS -amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; GBS - Guillain-Barre syndrome; MG -myasthenia gravis; OM -dermatomyositis; PM - polymyositis,

ysphagla

see Gastroenterology, G4

Apraxia

--------------------------'

Definition

inability to perform skilled voluntary motor sequences that cannot be accounted for by

weakness, ataxia, sensory loss, impaired comprehension, or inattention

Clinicopathological Correlations

Table 19. Apraxia

Description Tasts Hemispheres

Ideomotor 'inability to perform skilled learned motor 'blowing out amatch; left

sequences combing one's hair

Ideational 'inability to sequence actions ' preparing and mailing an envelope ' right and left

ConstnJctional' , inability to draw or construct ' copying afigure ' right and left

Dressing' 'inability to dress 'dressing , right

Refers specifically to the inability to carry out the learned movements involved in construction, drawing, or dressing; not merely the inability to

construct, draw, or dress, Many skills aside from praxis are needed to carry out these tasks,

N20 Neurology

..... '

.

,

.)-------------,

Lesions of the dominant parietal lobe

are characteriNd by Gerstmann's

Syndrome: acalculia, agraphia, finger

agnosia, and left-right disorientation.

Lesions of the non-dominant parietal

lobe are characterized by neglect,

anosognosia, and cortical sensory loss.

Behavioral Neurology/Cranial Nerve Deficits Toronto Notes 200S

Agnosia

Definition

disorder in the recognition of the significance of sensory stimuli in the presence of

intact sensation and naming

Clinicopathological Correlations

Table 20. Agnosias

Description Lesion

Aperceptive visual agnosia' inability to name or demonstrate the use of an object bilateral temporo-occipital cortex

presented visually 2' to distorted visual perception

recognition by touch remains intact

Associative visual agnosia' inability to name an object presented visually 2' to bilateral inferior temporo-occipital junction

disconnect between visual cortex and language areas

visual perception is intact as demonstrated by

visual matching

Prosopagnosia inability to recognize familiar faces in the presence of bilateral occipitotemporal areas or right inferior

intact visual perception and intact auditory recognition tempora-occipital region

Colour agnosia inability to perceive colour bilateral inferior temporlHlccipitallesions

Astereognosis inability to identify objects by touch anterior parietal lobe in the hemisphere opposite the

affected hand

Finger agnosia inability to recognize, name, and point dominant hemisphere parietal-occipital lesions

to individual fingers

Cranial Nerve Deficits

CN I: Anosmia

Clinical Features

absence of sense of smell

usually associated with a loss of taste sense; if taste is intact, consider malingering

usually not recognized by patient if it is unilateral

Classification

nasal: odours do not reach olfactory receptors because of physical obstruction

heavy smoking, chronic rhinitis, sinusitis

olfactory neuroepithelial: destruction of receptors or their axon filaments

influenza, herpes simplex, hepatitis virus, atrophic rhinitis (leprosy)

central: olfactory pathway lesions

congenital: Kallman syndrome (anosmia and hypogonadotropic

hypogonadism), albinism

head injury, cranial surgery, SAH, chronic meningeal inflammation

meningioma, aneurysm

Parkinson's disease

CN II: Optic Nerve

see Neuro-Ophthalmology, N24

CN III: Oculomotor Nerve Palsy

--"------_.......

Clinical Features

ptosis, eye is "down and out" (depressed and abducted), divergent squint, pupil

dilated (mydriasis)

pupillary constrictor fibres are on periphery of nerve

external compression of the oculomotor nerve results in umeactive pupil with

subsequent progression to extraocular muscle paresis

vascular infarction results in extraocular muscle paresis with sparing of the

pupil

Common Lesions

midbrain (infarction, hemorrhage)

may/may not affect pupil, may be bilateral with pyramidal signs contralaterally

Toronto Notes 200B Cranial Nerve Deficits Neurology N2I

posterior communicating artery aneurysm

..... ' ,

.l--------------,

pupil involved early, headache

cavernous sinus (internal carotid aneurysm, meningioma, sinus thrombosis)

Pupil sparing in CN III palsy suggests a

CN IV, V1 and V2/ and VI also travel in the cavernous sinus, pain and proptosis

vascular lesion.

may occur

Pupillary involvement in CN III palsy

ischemic (DM, temporal arteritis, HTN, atherosclerosis)

suggests external nerve compression.

pupil often spared

CN IV: Trochlear Nerve Palsy

-----------_.....

Clinical Features

diplopia, especially on downward and inward gaze

patient may complain of difficulty going down stairs or reading

patient may hold head tilted to side opposite of palsy to minimize diplopia

(Bielschowski head tilt test)

Common Lesions

trauma

ischemic (DM, HTN) most common

cavernous sinus (carotid aneurysm, thrombosis)

CN III and VI usually involved as well

orbital fissure (tumour, granuloma)

at risk during neurosurgical procedures in the midbrain because of long intracranial

course

only CN that exits posteriorly and crosses midline; left side symptom = right CN

pathology

CN V: Trigeminal Nerve

Trigeminal Nerve Lesions

Common Lesions

pons (vascular, neoplastic, demyelinating, syringobulbia)

petrous apex (petrositis)

orbital fissure, orbit, cavernous sinus (Ill, IV, VI also affected)

skull base (nasopharyngeal or metastatic carcinoma, trauma)

cerebellopontine angle

VII, VIll

acoustic neuroma, trigeminal neuroma, subacute or chronic

meningitis

other causes (DM, SLE)

herpes zoster

usually affects ophthalmic division (VI)

tip of nose involvement watch out for corneal involvement

(Hutchinson's sign)

Trigeminal Neuralgia (Tic Douloureux)

o

Definition

excruciating paroxysmal shooting pains in trigeminal root territory

Etiology

redundant or tortuous blood vessel in the posterior fossa, irritating the origin of the

trigeminal nerve

tumours of cerebellopontine angle (rare)

Clinical Features

characterized by: a series of severe, sharp, short, stabbing, unilateral shocks

usually in V3 distribution Vl' V2

pain typically lasts only a few seconds to minutes, and may be so intense that the

patient winces (hence the term tic)

may be brought on by triggers: touching face, eating, talking, cold winds

lasts for days/weeks followed by remission of weeks/months

F > M; usually middle-aged and elderly

physical examination is normal (if abnormal, think trigeminal neuropathy)

Investigations

clinical diagnosis (make sure no sensory loss over CN V)

sensory loss in trigeminal distribution suggests structural lesion (consider

demyelination, tumour)

N22 Neurology

.... ' ,

9')-------------,

CN VI has the longest intracranial

course and is vulnerable to increased

ICP, creating afalse localizing sign.

.... ' ,

9}-o-----------,

Forehead is spared in a UMN CN

Vlliasion.

Cranial Nerve Deficits Toronto Notes 2008

Treatment

medical

carbamazepine

c1onazepam, phenytoin, gabapentin and baclofen may also be beneficial

surgical (all methods are 80% effective, for -5 years)

microvascular decompression of redlUldant blood vessel at origin of trigeminal

nerve

percutaneous thermocoagulation

injection of glycerol/phenol into trigeminal ganglion

CN VI: Abducens Nerve Palsy

Clinical Features

inability to abduct the eye on the affected side

patient complainS of horizontal diplopia, which is worse on lateral gaze to the affected

side

Common Lesions

pons (infarction, hemorrhage, demyelination)

may be associated with facial weakness and contralateral pyramidal signs

tentorial orifice (compression, meningioma)

may be a false localizing sign in increased ICP

cavernous sinus (carotid aneurysm, thrombosis)

vascular - may be secondary to OM, HTN, or temporal arteritis

congenital- Duane's syndrome

CN VII: Facial Nerve

Clinical Features

LMNlesion

the entire face on ipsilateral side is weak

taste dysfunction to ant 2/3

both vollUltary and invollUltary movements are affected

impaired lacnmation, decreased salivation, numbness behind auricle,

hyperacusis

UMNlesion

weakness of contralateral lower face; frontalis is spared

Investigations

look for associated brainstem or cortical symptoms and signs to help localize lesion

Differential Diagnosis

idiopathic =Bell's Palsy

trauma

infection (otitis media, mastoiditis, Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes zoster virus

(HZV), HIV)

other

sarcoidosis, Group B Streptococcus, OM mononeuropathy, parotid gland

pathology

Bell's Palsy

see Otolaryngology, OT23

Definition

an idiopathic benign lower motor neuron (LMN) facial nerve palsy

Clinical Features

acute onset of unilateral (rarely bilateral) LMN facial weakness

diagnosis of exclusion

must rule out symptoms and signs of brainstem and hemispheric dysfunction

and systemic disease

etiology

lUlknown: thought to be due to swelling and inflammation of facial nerve in its

canal within the temporal bone

associated features which may be present

pain behind ipsilateral ear (often precedes weakness)

prodromal; viral upper respiratory tract infection (URII)

hyperacusls

decreased taste sensation

abnormal tearing (decreased lacrimation)

------------------

Toronto Notes 2008 Cranial Nerve Deficits Neurology N23

Treatment

patient education and reassurance

eye protection (because of inability to close eye)

artificial tears, lubricating oinhnent

patch eye at night

steroids (weigh risks and benefits)

start early after onset of symptoms (within 12 hours)

typical regime is prednisone 40-60 mg tapered over 7-10 days

acyclovir

controversial but used in the setting of a recent viral infection

Prognosis

spontaneous recovery in 85% over weeks to months

poor outcome

if complete paralysis lasts 2-3 weeks

if elderly or HTN

if symptoms of hyperacusis, abnormal tearing

Hemifacial Spasm

Definition

segmental myoclonus of facial muscles innervated by CN VII

Clinical Features

usually presents in the 5

th

or 6

th

decade of life

almost always presents unilaterally, beginning as myoclonus of orbicularis oculi

and can spread to other muscles after a few years

clonic movements eventually progress to tonic contractions of involved muscles

Etiology

majority of cases due to chronic irritation of facial nerve nucleus or nerve

(causing aberrant transmission within the nerve)

most common cause is idiopathic, caused by aberrant AICA artery compressing

facial nerve within the cerebellopontine angle

other causes

compressive lesions - tumor, AV malformation

non-compressive lesions - MS, stroke

Investigations

EMG - observe high frequency discharges of motor unit potentials that correlate

with clinically observed facial movements

MRl - detailed analysis of posterior fossa (especially with FIESTA sequence) to

obeserve aberrant blood vessels overlying the facial nerve

Treatment

carbamazapine and benzodiazepines (i.e. clonazepam) very useful in early/mild stages

botox injections - latency 3 - 5 days; duration 6 months

surgery - useful when idiopathic or compressive - treat with decompression of the

aberrant blood vessels - usually very favourable results

eN VIII: Vestibulocochlear Nerve

see Otolaryngology. OTl2

eN IX: Glossopfiaryngeal Neuralgia

Clinical Features

brief, sharp, attacks of pain affecting posterior pharynx

pain radiates toward ear and triggered by swallowing

taste dysfunction in post 1/3 of tongue

Treatment

carbamazepine

surgical lesion of CN IX

eN X: Va us Nerve

vagus nerve lesions result in

palatal weakness: affects swallowing

pharyngeal weakness: affects swallowing

laryngeal weakness: affects speech

..... '

.:\-------------,

An isolated cranial nerve defect,

especially of eN VI or VII, is most

likely the result of aperipheral,

and not abrainstem, lesion.

.... ,,

.l------------,

When screening for the presence of

dysphagia and assessing risk for aspi

ration, the presence of agag reflex is

inslJfficient. Rather the correct screen

ing test is to observe the patient drink

ing water from acup and looking for

coughing, choking, or "wetness" of

voice.

N24 Neurology Cranial Nerve DeficitsfNeuro-Ophthalmology Toronto Notes 2008

CNXI: Accessory Nerve

accessory nerve lesions

this nerve is vulnerable to damage during neck surgery

results in shoulder drop on the affected side, and weakness when turning the

head to the opposite side

CN XII: Hypoglossal Nerve

tongue fasciculation

deviation towards side of lesion

Ot er Differentials of [ower (c-N r , X, XI

and XII) Cranial Nerve Lesions

- - - - - - ~ - - - -

..... ' ,

,1----------,

intracranial/skull base

meningiomas, neurofibromas, metastases, osteomyelitis, meningitis

Clinical signs and symptoms sug-

brainstem

gesting lesions of both acranial

infarction, demyelination, syringobulbia, poliomyelitis, tumours (astrocytoma)

nerve and long tract signs imply a

brainstem localizing disease.

neck

trauma, surgC:'ry, tumours

Neuro-Ophthalmology

Acute Visual Loss

Etiology

ophthalmologic (seE' Ophthalmology, OP3)

corneal edema

glaucoma

vitreous hemorrhage

retinal detachment

optic nerve

optic neuritis

acute ischemic optic neuropathy (AlON)

arteritic

non-arteritic

compression by space occupying lesion (e.g. aneurysm)

vascular

TIA/amaurosis fugax

retinal artery occlusion

retinal vein occlusion

eNS

infarction/hemorrhage involving occipital lobe, optic radiations in temporal!

parietal lobe

lesions in optic tract/chiasm

Optic Neuritis

see also Optic Disc Edema, N25

most common etiology is multiple sclerosis (MS)

signs .

ipsilateral relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD)

swollen disc if anterior optic neuritis (- 33% of cases), not seen in retrobulbar

optic neuritis (-66% of cases)

treatment

acute treatment consists of coursE' of N methylprednisolone - reduces time to

maximal recovery; does not affect dE'gree of recovery

Anterior'lschemic Optic Neuropathy

~ . - . : : _ - . . . . . . , ; = - - - - - - - , . - -

see also Optic Disc Edema, N25

non arteritic

atherosclerotic variety

most common in elderly

no evidence of systemic diseasE'

diagnosis and treatment: similar to secondary stroke prevention

(e.g. anti-platelet thE'rapy, lipid lowE'ring)

Toronto Notes 2008 Neuro-Ophthalmology Neurology N25

arteritic

.... '

..\------------,

,

most common cause is giant cell arteritis (see Rheumatology. RH17)

diagnosis: elevated ESR; if suspect giant cell arteritis, must do temporal artery If you suspect the diagnosis of

biopsy Giant Cell Arteritis do not wait for

treatment - high dose steroids biopsy results!

recovery of visual loss usually poor Begin treatment immediately!

Amaurosis FugaxfrlA

"----------------------"

central retinal artery occlusion: complete loss of vision

branch retinal artery occlusion: altitudinal loss of vision

can be transient (amaurosis fugax) or permanent (retinal infarct)

diagnosis and treatment: see Stroke, N57

O ~ t i c Disc Edema

Table 21. Causes of Optic Disc Edema

Optic Neuritis Papilledema Anterior Ischemic Neuropathy

rapidly progressive central vision loss usually no visual loss until late acute field defects

acuity affected possible transient obscuration decreased colour vision

decreased colour vision variable acuity

normal colour vision

Other symptoms tender globe, painful on motion headacne typically unilateral

rarely bilateral in adults nausea

may alternate eyes in multiple sclerosis vomiting

focal neurological deficits

Pupil no anisocoria no anisocoria no anisocoria

RAPD present 'no RAPD RAPD present