Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Aligning curriculum, assessment, and pedagogy to improve learning

Загружено:

elbalazzaroniИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Aligning curriculum, assessment, and pedagogy to improve learning

Загружено:

elbalazzaroniАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of education Vol. 24, No.

2, August 2003

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling: aligning curriculum, assessment and pedagogy

DEBRA HAYES, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia

ABSTRACT

Schooling interfaces are not very permeable. Despite sustained efforts by many on either side, they remain barriers that are crossed with difculty. As a result, educators working within schools may feel isolated while those on the outside may feel at a loss how to intervene. This paper attempts to work at this interface and to speak to educators, policy makers and academics who are differently positioned on either side of it. The paper attempts to provide an account of schooling that makes learning one of its effects and that makes a difference for students from low-income families. This account of schooling is underpinned by a commitment to aligning curriculum, assessment and pedagogy and developing a common language and understanding of these message systems of schooling. Findings from the large-scale Queensland School Reform Longitudinal Study and descriptions of teachers work are integral to this discussion that addresses the enduring concern for social justice in schools.

It is important to avoid a well-meant but essentially patronizing social determinism that allows teachers to collude with pupils from less well-off backgrounds to avoid real learning as irrelevant or beyond them For these pupils as much as any others, the teacher must teach and must maintain with cheerful determination the aim of making learning possible. (Marland, 1975, p. 9) Michael Marland wrote these words over a quarter of century ago in his book The Craft of Classroom Teaching (1975). That the words are still relevant today, albeit sounding a little quaint, attests to the ability of classrooms and schools to resist change and maintain essentially modernist and universal forms in a sea of shifting economic, political and social formations. Marlands survival guide does for classroom teachers what Ralph Tylers Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction (1949) did for curriculum planners many years earlier; they are handbooks for managing classrooms and schools, respectively. Critical analysis of such texts rightly points out that they are decontextualised, highly functionalist accounts of schooling. However, they redeem themselves somewhat by taking seriously longstanding calls by teachers and administrators for practical help in

ISSN 0159-6306 print; 1469-3739 online/03/020225-21 2003 Taylor & Francis Ltd DOI: 10.1080/0159630032000110757

226

D. Hayes

managing and improving classrooms and schools. These calls persist and have been reiterated recently in an Inquiry into the Provision of Public Education in New South Wales, Australia1 (Vinson et al., 2002). In the Findings in brief document, three main calls were identied: (1) helping children to be better learners; (2) improving morale in schools; and (3) teaching all students to their best ability. The track record of those who have attempted to respond to these calls is not good. Policy makers have often been criticised for discounting the role of teachers: teachers have been the agents rather than the objects of educational change (Hargreaves, 1997), and the objects rather than the subjects of policy (Ball, 1997; Mahony & Hextall, 2000). Similarly, researchers who have sustained a longstanding interest in school effectiveness and improvement have been criticised for over-simplifying the complexity of schools and blaming teachers for students under-achievement (Slee et al., 1998). Additionally, and despite some of their most salient ndings, school effectiveness and improvement researchers have been criticised for failing to help students from traditionally underachieving groups. This nal criticism has been made consistently by Thrupp (see e.g. 1999 and 2002), who claims that school effectiveness and improvement research is inadequate to bring about the fundamental changes that are needed to provide social justice in education because it actively distracts attention from this larger agenda by over-emphasising school-based solutions, even though these researchers have only been able to show very modest school effects on student outcomes. Though Thrupps claims should be acknowledged, it is important not to let his criticisms also distract us from working, by every means, for social justice in education. Despite their failings, the school effectiveness and improvement literatures have maintained a sustained focus on those features of schools which make a difference. While genuine attempts have been made to respond to the concerns of teachers and administrators, the fact remains that there is limited engagement by policy makers and researchers with the concerns of teachers and their daily struggles to maintain what Christie (2001) has called the rhythms of schooling. A key factor in continuing to take seriously their concerns is to acknowledge that those who respond are likely to be differently positioned within the project of schooling and postmodern conditions. Generally, teachers and school administrators express a strong desire to know what works and what will make a difference in their efforts to improve student learning outcomes. They are attracted by accounts of schooling that detail techniques for enhancing school and teacher effects. Whereas those whose work is primarily located in the policy eld tend to be more inuenced by accounts of schooling that recognise the systemic nature of educational provision and the need for the system to inuence and monitor local variations. The emphasis on performativity within the postmodern state frames the concerns of policy makers around a technicist modus operandi (Lingard et al., 1998) that sees them maintain their interest in maximising outputs, while nding new ways to minimise inputs. In contrast, the diverse interests of academics are less likely to be either technical or technicist in nature, but are perhaps better described as attuned to schools as particular technologies of power and knowledge. In addition, these sets of interests operate within specic contexts and yet are embedded within global ows (Appadurai, 1996): equity has been reframed towards performativity (Ball, 2000, p. 1); the market had been introduced as a source for renancing schools and further differentiating between schools based on their ability to compete in this new environment (Chapman, 1996; Yeatman, 1993); and moves towards school-based management reect how new managerialism is changing the relationship between the centre and the periphery by devolving on the one hand and centralising on the other. (Christie & Lingard, 2001)

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

227

In this paper, I explore an account of schooling which threads together the concerns of those who attempt to make a difference in schools, while acknowledging their positions and locations within this hybrid modernist-postmodernist moment (Lingard et al., 1998, p. 97). A critical concern is how schools that serve low-income communities are reconstituted at this time when equity programmes are being dismantled. For example, the US work of Newmann et al. (1996) on authentic pedagogywhich is located within the US sociological school effects tradition (Lingard et al., 1998)has been of real interest to senior bureaucrats in Education Queensland (Lingard et al., 2002). Their interest was reected in the commissioning of the large-scale Queensland School Reform Longitudinal Study (QSRLS) 19982001 (Lingard et al., 2001). However, this systemic support for Newmanns research and its core claim that school restructuring can produce more equitable student outcomes occurred at the same time as support for school-based management produced a weakening of many central equity polices in Queensland and elsewhere in Australia. Within this context, in which redistributive funding is critically important for many schools but not forthcoming in current neoliberal policy regimes, Christie and Lingard (2001) argue that it is important to set the terms of accountability in ways which reect the deeper educational and moral purposes of schooling, including those usually framed under the rubric of social justice (p. 12). Setting the terms of accountability in this way reframes longstanding interests in making the difference (Connell et al., 1982; Christie, 1991; Thomson, 2002) in terms of which differences make a difference (Lingard et al., 1998). Hence, a further purpose of this paper is to provide an account of schooling that makes a difference for students from low-income families by having positive effects on their learning as indicated across a range of academic and social indicators. In other words, I want to focus on the terms of accountability that make learning an effect of schooling for all students. Schools are so utterly familiar to those of us who live in industrialised countries that how they work is generally taken for granted. Even the differences between schools are often thought to be straightforwardly linked to the type and location of schools. This tendency of schools to elude scrutiny is not because their functioning is transparent but because, like other discursive formations, schools become taken-for-granted elements of our everyday experience, so much so that focusing on how they operate can seem like a waste of time. Hence, focusing on how schools function is not meant to signal a hankering for functionalist accounts of schooling, but is to place their functioning and effects under scrutiny, in order to call these into question and to identify points of intervention. A core assumption underpinning this discussion is that a pause in activities is necessary in order for those who work in schools to make explicit how schools function and for them to function as places of learning. Not all schools set aside time within the school day for teachers to meet for professional dialogue. In these schools, opportunities for sharing ideas, collective problem solving, and planning must compete with the other demands and pressures on teachers time. More often than not, this time is squeezed off the agenda or reduced to a minimum by competing concerns. In the absence of opportunities for collective reection, schools tend to become busy places where a lot happens and where learning relies on the capacity of individual teachers in classrooms, rather than on the planned alignment across the school of the effects of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. Bernstein (1973) conceptualises formal educational knowledge as being realised through these three message systems. He states that curriculum denes what counts as valid knowledge, pedagogy denes what counts as a valid transmission of

228

D. Hayes

knowledge, and [assessment] denes what counts as a valid realisation of this knowledge on the part of the taught (p. 228). I argue that the primary purpose of pausing and placing how schools function under scrutiny is to align these systems in ways that support the learning outcomes of both students and teachers. It is not my intention to outline a prescription for these message systems, a ` la Marland (1975) and Tyler (1949), but to argue that the effects of curriculum, pedagogy and evaluation need to be continually monitored and negotiated at the local level though a shared understanding of each system, a common language for discussing them and a mechanism for aligning their purposes.

Curriculum: a shared vision for learning and a foundation for action

If an educational program is to be planned and if efforts for continued improvement are to be made, it is very necessary to have some conception of the goals that are being aimed at. These educational objectives become the criteria by which materials are selected, content is outlined, instructional procedures are developed and tests and examinations are prepared. All aspects of the educational program are really means to accomplish basic educational purposes. Hence, if we are to study an educational program systematically and intelligently we must rst be sure as to the educational objectives aimed at. (Tyler, 1949, p. 3) A shared vision for learning makes explicit what is to be learnt or, in the words of Tyler, the goals that are being aimed at. It provides a foundation for action, in particular a foundation for pedagogy and assessment, as well as a baseline for evaluating the effects of schooling. Without common and agreed goals, teachers are forced to work in isolation, acting upon what they consider to be important learning goals; they must rely upon their own professional and personal experiences to inform their actions. But these may be vastly different from the life trajectories of their students. These circumstances can produce the kind of well-meant but essentially patronizing social determinism that allows teachers to collude with pupils from less well-off backgrounds to avoid real learning as irrelevant or beyond them that was described by Marland in the opening quotation in this paper. Even if there are similarities in these experiences, it should not be assumed that there will be a natural resonance between teachers pedagogies and the types of outcomes from schooling that students, their families and society may desire (cf. Anyon, 1995). In the US, advocates of standards-based reforms hoped that outlining what students should know and be able to do would overcome some of these problems. According to Darling-Hammond (2003), some of the more successful reforms in the United States have emphasized the use of standards for teaching and learning to guide investments in better-prepared teachers, higher quality teaching, more performance-oriented curriculum and assessment, better designed schools, more equitable and effective resource allocations, and more diagnostic support for student learning (p. 2). However, she also observes that mid-course corrections to standards-based reforms are needed and that these should focus on:

assessing meaningful learning using high-quality measures tied to standards and supplemented by local indicators of learning; using assessment data to inform curriculum reform and guide investments in better-

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

229

prepared teachers and other initiatives that support improved learning conditions rather than to punish students and schools for low performance; developing high-quality teaching in schools that provide equitable access to curriculum that can enable students to learn the standards. (Darling-Hammond, 2003, p. 8)

These corrections reect the need to align the three message systems of schooling. The rst correction relates to a curriculum that is attuned to local concerns but informed by broader agreements on standards, the second to using assessment to support learning, and the third to pedagogy. Although the US situation is very different to the Australian, I want to explore why the corrections Darling-Hammond spells out for the US have relevance for Australia. While the US has gone down the standards path, recent reforms in Australia suggest that the latter country has gone down the values and purposes path. The New Basics Framework in Queensland and the Essential Learnings Framework in Tasmania illustrate this point. In Queensland, the New Basics have been identied as Life Pathways and Social Futures, Multiliteracies and Communications Media, Active Citizenship, Environments and Technologies (Education Queensland, 2001). Similarly, in Tasmania the essential learnings have been identied as Communicating, Personal Futures, Social Responsibility, World Futures and Thinking (Department of Education, Tasmania, 2002). Like standards-based reforms, these values/purposes-based reforms attempt to spell out what students should know and be able to do, but there is widespread variation in how those reforms are achieved through schooling. In both the US and Australia, a range of implementation regimes have been adopted in various states. The heavy emphasis in the state of New South Wales (NSW) on the Higher School Certicate as a nal external set of examinations has some of the characteristics of high-stakes testing in the US. However, this has been softened somewhat in NSW by combining the results of these examinations with school-based assessment, the implementation of standards-based examinations since 2001, and limited public reporting of results. Even so, the presence of selective schools and selective streams in otherwise comprehensive schools produces a system of public schools that is highly differentiated according to student achievement. In this way, NSW reects the situation in the US, where mandates for student testing are detached from policies that might address the quality of teaching, the allocation of resources, or the nature of schooling (Darling-Hammond, 2003, p. 1). As a result, disproportionate numbers of students in NSW from low-income families, isolated areas and Indigenous background continue to disengage from schooling and underperform relative to other students. This highlights the way in which local variation in schools, such as differences in intake and organisation, produce local and persistent variations in the curriculum. As Teese and Polesel argue, a hierarchical curriculum needs a stratied school system (2003, p. 12). Vigilant and relentless alignment of local concerns with the broader goals of schooling is one approach to resisting the type of curriculum differentiation that locks some students into limited outcomes from schooling. The need for greater alignment between the three message systems was starkly illustrated in a survey of 440 teachers whose classrooms were observed as part of the QSRLS (Lingard et al., 2001). A strong misalignment was apparent between the types of assessment tasks which teachers utilised and their stated pedagogical goals. Although they claimed that higher-level skills, citizenship and academic excellence were pedagogical goals that they valued, these goals were not reected in the assessment tasks that they submitted for coding by the research team. These results emphasise the need for a negotiated and shared vision for learning aimed at establishing a foundation for action,

230

D. Hayes

particularly for classroom practice, which is aligned across the school and with community expectations. Darling-Hammonds rst correction to standards-based reforms claims that assessing meaningful learning using high-quality standards should be supplemented by local indicators of learning. At the local level, this may be negotiated through broad-based consultation. A working model for this type of consultation is the process of co-construction that was used in Tasmania to develop the Essential Learning Framework. The process of co-construction clearly recognises that improvements in education are much more successful if stakeholders are actively involved. The methodology puts practitioners at the heart of the curriculum development process and ensures relevance, practicability and usefulness. (Department of Education, Tasmania, 2002, p. 6) This process of co-construction provides a means by which local plans and concerns can be articulated with broader social concerns. These broader concerns have been articulated in Australia through The Hobart Declaration in 1989 and more recently, The Adelaide Declaration on National Goals for Schooling in the Twenty-First Century (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training & Youth Affairs [MCEETYA], 1999). These declarations were agreed to by all state and territory schooling systems in Australia. The Adelaide Declaration states that when students leave schools they should have:

the capacity for, and skills in, analysis and problem solving and the ability to communicate ideas and information, to plan and organise activities and to collaborate with others; self-condence, optimism, high self-esteem and a commitment to personal excellence; the capacity to exercise judgement and responsibility in matters of morality, ethics and social justice; the capacity to think about how things got to be the way they are, and to be active and informed citizens; employment-related skills, the use of technology and the ability to contribute to ecologically sustainable development.

While there is widespread agreement on the importance of these goals, we should not assume agreement on their substance. The current Australian governments approach to refugees, Aboriginal reconciliation and foreign policy clearly demonstrates that what counts as social justice, informed citizenry and sustainability are highly contested. Within this context, it is appropriate and necessary that local concerns about what counts as educational goals and indicators of learning should be actively negotiated and articulated. The central importance of co-constructing a shared vision for learning is that it provides a foundation for coordinated action, but there is no simple formula for such action, and the tendency for power and competing political agendas to play out in these processes, at all levels, should not be underestimated. At the American Association for Research in Education Conference in Seattle in 2001, a number of Chicago-based principals of schools where students had greatly improved their results on standardised measures were invited to describe how they had transformed their schools. One of the principals summed up his schools approach by acknowledging that his school could have taken many directions, but that the most important feature of his schools efforts was that the teachers all agreed on the

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

231

direction they would take. Moving in a particular direction requires planned and coherent action. It is not sufcient to develop a shared vision for learning and then to rely upon taken-for-granted understandings of how schools work to operationalise this vision. Even the most talented and professional educators need to align their efforts, otherwise they may nd themselves heading off in different directions. Just as the vision for learning needs to be negotiated and shared, so too does the manner in which the direction is set. At Bankstown Girls High Schools (GHS) in Sydneys southwest, over a number of years teachers have developed a systematic approach to setting an agreed direction. This initiative has been led by Stephanie Kingston, who coordinates the schools involvement in a remnant redistributive funding programme aimed at addressing the needs of disadvantaged students, together with Jane Fulcher, who leads the schools support staff. When describing their approach they emphasise the need for whole school consistency in developing, expressing and achieving:

exit outcomes and expectations of high standards; school targets arising from evaluation of programmes, professional dialogue and current trends in education; school priorities to maintain identied ongoing school needs, e.g. literacy; the purpose of learning programmes; agreement on the level of thinking/standards and outcomes to be assessed; explicit assessment criteria that clearly articulate the standards required; explicit teaching and delivery of: 1. literacy skills 2. thinking skills 3. numeracy skills 4. technology skills 5. welfare strategies and expectations 6. linking key learning area (KLA) skills to School to Work planning alignment of initiatives and special programmes such as Year 7 Orientation; recording and reporting procedures.

A key element of developing such a shared vision for learning at the school level is sustained and broad-based negotiation; this provides a foundation for action. In the following discussion, I consider how to back up this foundation for action through assessment practices and then pedagogy. A core assumption is that the process of aligning curriculum, pedagogy and assessment has coherence and purpose that is recognisable at different levels of the school. In other words, the issues and questions faced by teachers as they develop learning programmes for students are similar in nature to those faced by heads of departments as they coordinate sequence and scope within their subject areas, and similar again to those faced by school executives as they build the capacity of their teachers to head in the direction of a shared vision for learning. Backing up this foundation for action involves building coherence of purpose and capacity for supporting learning across the school.

Backward Mapping: putting assessment upfront

Backing up the curriculum through assessment and pedagogy may be thought of as a process of backward mapping. This notion was developed by Richard Elmore (1979

232

D. Hayes

1980) as an alternative form of policy implementation to the more familiar forward mapping. I work with the notion here as a way of accounting for how schools may build coherence across curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. [Forward mapping] begins at the top of the process, with as clear a statement as possible of the policymakers intent, and proceeds through a sequence of increasingly more specic steps to dene what is expected of implementors at each level . [Backward mapping begins] with a statement of the specic behavior at the lowest level of the implementation process Only after that behavior is described does the analysis presume to state an objective; the objective is rst stated as a set of organizational operations and then as a set of effects, or outcomes, that will result from these operations. (Elmore, 19791980, pp. 602, 604) Thus Elmore conceptualises policy implementation as falling into one of two clearly distinguishable approaches: forward mapping and backward mapping. There is a signicant inversion in how he denes these approaches, such that backward mapping challenges implementation efforts that attempt to steer at a distance or by decree; it involves setting a direction based on agreed objectives at the lowest level of the system rather than beginning at the top of the process. In the case of schools, I interpret this to relate to the broad range of academic and social outcomes identied for students and teachers. Elmore suggests that Having established a relatively precise target at the lowest level of the system, the analysis backs up through the structure (19791980, p. 604). Again, there are multiple ways in which this suggestion may be interpreted in schools, but in order to build coherence and maintain alignment across the three message systems it becomes essential to determine what the objectives at the lowest level of the system are, and what counts as success. This approach asks the question upfront: What do we want students to be able to know, value, understand and do? Answering this question makes assessment integral to teaching because backward mapping forces a consideration of how such performances will be achieved, measured and taught. In addition, this approach places assessment upfront and requires it to be planned before related learning activities commence. This placement mobilises pedagogy in support of assessment and, more importantly, in support of learning outcomes; it builds coherence by requiring that teachers understand the scope and sequence of outcomes across all learning programmes, not just at the level they teach. A key set of questions for teachers becomes: What outcomes have individual students attained? What outcomes am I responsible for teaching? How will I know when these outcomes have been achieved? Teachers at Bankstown GHS have applied this process of backward mapping to planning across the curriculum and within subject area specic units of work. Shown in Figure 1 is the planning tool they have developed to backward-map the schools co-constructed exit outcomes onto teaching and learning experiences. This planning tool traces how the curriculum is backward-mapped through assessment and pedagogy in general terms, but it is designed to be applied to more specic learning outcomes. The act of negotiating the process is intended to coordinate and direct teachers work towards a common purpose. It is framed in ways that reect the elements of the schools agreed direction listed earlier. This planning tool demonstrates how one school is attempting to align the many factors that contribute to setting a common direction and building coherence across the message systems of schooling. It is a complex task and there is no real guarantee of

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

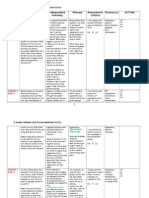

Table 1.

233

Elements of the QSRLS coding instruments*

Productive pedagogies Problematic knowledge Productive assessment tasks Problematic knowledge: construction of knowledge Problematic knowledge: consideration of alternatives Higher-order thinking Depth of knowledge: disciplinary content Depth of knowledge: disciplinary processes Elaborated written communication Metalanguage Problem connected to the world beyond the classroom Knowledge integration Link to background knowledge Problem-based curriculum Audience beyond school Students direction Explicit quality performance criteria

Dimensions Intellectual quality

Productive performance Problematic knowledge

Higher-order thinking Depth of understanding

Higher-order thinking Depth of knowledge Depth of students understanding

Elaborated Substantive written conversation communication Metalanguage Connectedness Connectedness Connectedness to the to the world world beyond the beyond school classroom Knowledge integration Background knowledge Problem-based curriculum Supportiveness Students direction Explicit quality performance criteria Social support Academic engagement Student self-regulation Cultural knowledges Active citizenship Narrative Group identities in learning communities Representation

Recognition of Cultural difference knowledges Responsible citizenship Transformative citizenship

Cultural knowledges Active citizenship Narrative Group identities in learning communities

*For further information see the Education Queensland website: http:// education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics/html/pedagogies/pedagog.html Items incorporated from the CORS (Centre for Organizational Restructuring) concept of authentic pedagogy.

234

D. Hayes

success, even when the map is followed closely; however, being explicit about how a direction is set provides opportunities to inuence it develop a common purpose. This tool also suggests that aligning curriculum with pedagogy through assessment requires a broad range of classroom practices because learning in the 21st century is reected in a broad range of academic and social outcomes. The analysis of assessment tasks, student performances and classroom observations in the QSRLS provided a unique opportunity to examine the links between curriculum, pedagogy and assessment in a large number of classrooms. During the three years of the study, 975 classes were observed in 24 schools. In addition, teachers who were observed were asked to submit whole class sets of student work samples for at least one assessment task of their choice. The English and history samples were then coded by a group of teachers in Queensland and the mathematics and science samples were coded by another group of teachers in NSW. Throughout the process of coding hundreds of students work samples, the teachers who undertook the coding reected on their own practice and were challenged to develop some examples of assessment tasks that illustrated the codings they were applying. Drawing on their own teaching backgrounds, the NSW coders divided into one group that focused on upper primary maths and a second group that focused on senior secondary biology. While both groups set about developing a rich assessment task,2 one group modied an existing assessment task whereas the other began with a resource from which they had rst developed some teaching strategies. These quite different approaches demonstrate that there is no strict formula for backward mapping, and that the process of aligning curriculum, pedagogy and assessment can start at numerous places. Reproduced in Figure 2 is the assessment task for Year 10 science that was developed by Chris Greef and Martin Lauricella, who were both science teachers at Asheld Boys High School (BHS) when they developed this task. They selected relevant outcomes from the NSW Stages 45 Science Syllabus3 reecting a range of academic and social outcomes. They also took into consideration their schools prioritising of literacy skills as reected in their choice of a letter as the major task. Also of particular note is the assessment grid that has been designed to communicate explicit performance criteria to students. This assessment task was handed out to students at the start of learning activities for this unit and it was designed to scaffold these activities for both students and teachers. Since this task was handed out before learning activities commenced, and since classroom activities were generated by it, students were able to negotiate and clarify what was expected of them and to receive feedback on early drafts of their writing. Assessment grids such as the one shown in Figure 2 are an important means of conveying to students the types of performances expected of them, but they also work in ways that help translate the curriculum into pedagogy. Within the Australian context, the formulation of Rich Tasks in the New Basics Framework (State of Queensland, 2001) has raised the level of understanding of how to connect the curriculum (New Basics) through assessment (Rich Tasks) to pedagogy (Productive Pedagogy) at the systemic level. The technique for formulating standards of student performance within this framework is described in the following ways:

and

[Setting standards for student performance on each of the completed Rich Tasks] involves convening panels to scrutinise the indicative standards descriptors written at the same time the tasks were composed. Since the tasks are transdisciplinary and connected to the wide world, panelling of their desirable

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

235

Exit outcomesshared expectations of high standards Academic performance

Demonstrating higher-order thinking Engaging in critical literacy Problem solving

Social performance

Engaging positively on learning Effectively communicating in a variety of contexts Demonstrating responsible citizenship

What do we want students to be able to know, value, understand and do?

Purpose Targets

To empower students to make informed and appropriate choice To develop a culture of thinking in our school through the explicit teaching of higher-order thinking skills across the curriculum To align teaching practice to assessment by putting assessment rst and incorporating the perimeters for consistency of teaching judgement

School priorities Analyse syllabus documents to determine outcomes and standards to be assessed

In order for an assessment piece to promote agreed outcomes it should: expect students to perform work of high intellectual quality; enable students to demonstrate a connectedness between their work in class and the world beyond the classroom; provide the support necessary for them to achieve these outcomes; and give students opportunities to demonstrate recognition of difference.

Assessment task and marking criteria

Explicit teaching of Literacy Thinking Numeracy Welfare Technology Skills Skills Skills Skills Careers

Figure 1. Bankstown Girls High School: learning for a changing future.

features requires expert panellists with a range of sensitivities and understandings, ideally covering the following: disciplines or key learning areas; transdisciplinary understandings; expertise in pedagogy at the particular age level; practitioners in the community; expertise in standards-based assessment; and familiarity with the New Basics Framework. (p. 34) This description illustrates the complexity and scale of aligning curriculum, assessment and pedagogy in meaningful and negotiated ways, particularly at the systemic level; and

236

D. Hayes

Description of task

One type of current genetic technology used on humans is to be analysed. Issues like discovery, development, application, costs and benets of the technology are explored. Ethical issues and possible impacts on society are also raised. Students prepare a written report on the technology for the teacher and also write a letter to an appropriate institution, government body, newspaper or individual. The report reects the ndings of the research as well as some ethical issues. The letter argues for the appropriateness of that technology and includes some recommendations.

Outcomes (from relevant syllabus documents)

evaluate the impact of applications of science on society and the environment discuss, using examples, the positive and negative impacts of applications of recent developments in science analyse how current research might affect peoples lives evaluate the potential impact of some issues raised in the mass media that require some scientic understanding describe scientic principles underlying some common technologies describe some benets and problems and some of the social and ethical issues of using biotechnology access information from a wide variety of secondary sources use a range of sources, including CD-ROMs and the internet, to access information use key words, skimming and scanning techniques to identify appropriate information summarise information from identied oral and written secondary sources select and use appropriate forms of communication to present information to an audience select, and use appropriately, a discussion, explanation, procedure, exposition, recount, report, response or experimental record for oral or written presentation

Time

Approximately 4 weeks, including lesson time

Assessable items

Report

One reproductive genetic technology for human application is researched and described. It includes a description of the technique, the discovery/development of the technique, costs and benets of the technology, alternatives to the technique, regulation of the technique, implications for the health and welfare of the parents and baby, implications for society or groups within society such as different religious, socioeconomic, cultural and geographic groups, and a recommendation. The report is not longer than 1,000 words and may include diagrams/pictures. A reference list or bibliography is part of the report.

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling Letter

237

A letter outlining major recommendations and their justications is to be sent to a selected institution, government body, newspaper or individual. The formal letter is not longer than 500 words. On a separate sheet the student briey justies the selection of the addressee.

Notes

Notes and/or drafts are to be handed in separately.

Guide questions

Who are the stakeholders? Who benets from this technology? How does this technology work? What is it designed to do? What are the benets of the technology for all who are involved (doctors, researchers, company directors, shareholders, parents, babies)? What are possible dangers? How much does it cost? Who is paying? Who decides, or should decide, if the technology is to be used? Or limited? Or banned? Or restricted to certain people? Who are the major players in its development? Doctors? Researchers? Pharmaceutical companies? Are there cultural, religious, ethical conicts? Are there any existing alternatives that could be used instead of this technology? How are they better? Or worse? What are the barriers to making this technology equitably available to all sectors of society? Are there any current restrictions or regulations concerning the application of this technology in Australia? Are other countries very different? IVF for parents IVF for single or gay women Cloning of organs Cloning of whole organisms Stem cell cloning Gene therapy Germ line genetic therapy Genetic screening for inheritable diseases

Possible areas for research

Assessment grid

Aspect Description Discovery Highly developed Link to prior knowledge made Problems highlighted Competent Explanation provided Steps linked Developing Briey described Timeline given

238

D. Hayes

Evaluation Alternatives Regulation

Costs, benets evaluated Different cultures valued Alternatives evaluated Limitations presented

Costs, benets described Alternatives described Regulations described Major short-term implications given Comparisons made between groups/stakeholders Evidence given Formal language Well spaced 3 various references Wide range of resources Many notes Summaries of references provided

Costs, benets stated Alternatives stated Regulatory bodies named Anecdotal implications given Some listed for some groups Personal opinion presented Title Paragraphs Neat 2 references Narrow range of resources Some notes References paraphrased

Implications for Long-term, social parents, baby implications given Implications for Long-term society implications predicted Recommendation Well argued Presentation Researching Scientic terms Correct grammar Clear structure 3 various references Well-structured notes Evidence of analysis and synthesis

Figure 2.

Genetic and Reproductive Technologies for Humans.

the trial of this framework in 49 Queensland schools is providing an opportunity to assess this approach to alignment on a large scale.4 However, I want to conclude this section by returning to the process of alignment on the smaller, and perhaps even more critical, scale of the classroom by focusing on one teachers classroom practice. Margaret Simpsons career in public education spanned forty years, and for the last 11 years she was a primary principal. During the 1980s, she taught Year 6 at a suburban primary school in a low-income community made up of many new immigrants in Sydneys southwest. The children in this class were aged between 10 and 12. They were all efcient readers and developing writers. They came together four times a week to work on their writing skills. Many were bilingual, and most of them experienced occasional problems with tense and with the use of rst and third person in writing. Margaret designed the following exercise to allow them to explore these areas. The children had been immersed in the stories of the and the and storytelling, drama, art and the making of a lm formed the background to this task. The task: In groups, make life lines for each of the main characters in the Iliad. Draw on all of the resources you know to complete it.

Odyssey Iliad

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

239

Select a character who appeals to you and choose a point on the life line of that person. Look through the characters eyes and describe what is going on. REMEMBER: The character can not know any of the events that will happen from that point on, even though you and your reader know. REMEMBER: How the character might feel about the other characters, which of them are related, are friends or enemies. REMEMBER: That the character not only takes part in the action but has FEELINGS about the action. REMEMBER: That I the reader, should gradually come to understand who I the writer is. You must drop clues in the text that help me little by little to do this. Perhaps your name will not ever be mentioned. REMEMBER: That I the reader, DO know the coming events and use my knowledge to contrast with your characters interpretation of events. For instance I know what the Horse is the Trojans do not. Reecting on this task, Margaret commented, I cant believe I asked this primary bunch from a big multicultural school to tackle such a thing even after working together most of the year. Mirvette was from a large Lebanese family. There are many others that I love but this really moved me. It also has resonance for today I remember that her rst effort was so mundane, devoid of any feeling. I think she had four or ve goes at it, and then I remember the two of us sitting weeping over the nal piece. Where is she now? Andromache speaks: I cant convince him to stay at home today. He is determined to go. He is so tired. Anything could happen to him if he goes out there today. What will happen to his child if something happens to him? He told me he must go. He said, what would people think if the leader stayed at home because his wife was frightened? As he left, I held back my tears and didnt make a sound but in my heart I fear very much for Hector and what this day might bring. As I do every day, I will go to the walls with Hecuba his mother and Helen, my sister-in-law, to watch. I cant bear to wait at home till someone brings me bad news. I will hold little Astynax in my arms and pray that he will never be down there ghting for his city like his father. One day Death must come for Hector and I very much fear that this is going to be the day. Mirvette speaks: I have stepped into the character of Andromache when her husband Hector, Prince of Troy, went out to ght his last battle. Margaret comments, of course he dies and his body is dragged around the city behind Achilles chariot. The baby Astynax is thrown from the city walls when Troy falls, Andromache is enslaved, but of course Mirvette knows all that and chooses this very personal moment to describe. These recollections were conveyed to me in personal correspondence, and I include them here to emphasise the enduring characteristics of good teaching; that students need

240

D. Hayes

opportunities to practise the performances we desire for them in a supportive challenging environment; and that classrooms may be places of learning for teachers as well as students. In this section, I have emphasised the importance of linking assessment to the curriculum and making explicit the types of performances we expect from children. Many educators nd this sequence counter-intuitive and their natural tendency is to develop learning activities rst and assessment tasks towards the completion of these activities. Again, it is important to emphasise that my core argument is not that backward mapping is the way to make learning an effect of schooling, but if learning is to be an effect, it requires coordinated action that aligns the three message systems for this purpose.

only

Mobilising Pedagogy in Support of Assessment

The more you look at schooling in practice, the more you study research and observation, and the more you consider the real problems of helping young people learn, the more you are forced to the simple conclusion that individual teachers are the most important factor The encouraging thing is that [the art of teaching] can be learnt, practised and improved. It is not merely natural, and when it has been acquired you and your pupils will enjoy your time together in school more. (Marland, 1975, p. 1) There is perhaps no greater contribution to enhancing the likelihood of learning than teachers and students enjoying their time together in schools. This does not mean that everyone is happy all the time. Enjoying learning sometimes involves struggling with difcult concepts, practising new skills, persevering with problem solving, negotiating and compromising. When learning is an effect of classroom practices, both teachers and students experience these rewards and challenges because they are places where teachers are learning too. In this section, I focus on pedagogy and my core concern is how to develop a shared language that supports the alignment of pedagogy with assessment and the curriculum. Despite the importance of quality teaching and learning, I have left this section until last because I believe that pedagogy is best shaped by the curriculum and assessment. For this reason, I nd it helpful to conceptualise pedagogy as the means by which the curriculum and assessment are mediated in the classroom. Since the curriculum and therefore assessment reect a broad range of academic and social outcomes, it follows that teachers need a exible and highly developed bank of pedagogical skills to mediate these in their classrooms. The work of the National Schools Network (NSN)5 over many years suggests that one of the most effective ways for teachers to develop these skills is in professional dialogue with each other. The NSN has supported the use of the Tuning Protocol that was initially developed by the Coalition of Essential Schools, as a form of collective inquiry that allows [teachers] to work together to improve student learning (Brown Easton, 2002, p. 28). During the 1990s, Asheld Boys High School was one of the Networks schools and it was widely recognised for its teaching teams under the leadership of Ann King (19922002). This time of reculturing and renewal followed a period in the late 1980s of rapid decline in enrolments and the local communitys loss of condence in the school (King, 1996a). On reecting upon the progress and development of teams over a period of time, Ann observed, I believe the introduction of collaborative teams to be the most signicant

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

241

aspect of reform at Asheld. Their signicance lies in the subtlety of the energies they release. People do enjoy working togethersharing, hearing from others, conducting a team dialogue Initially they seem to concentrate on student welfareoften they begin anecdotally but they soon move to more purpose-driven work. Some teams take much longer to deal with issues of pedagogy and learning Teams have been instrumental in placing kids learning at the forefront of our priorities, followed closely by staff learning and reection on classroom practice. (King, 1996b, pp. 1617) Reection on classroom practice does not come naturally to the vast majority of teachers. It requires a shared language to talk about pedagogy and a commitment to actively focusing on teaching and learning. Apart from the competing demands of welfare and organization, teachers in any one school have generally experienced very different pre-service and in-service professional development. This means that their professional languages are not easily interpreted or shared, and they may be balkanised by their knowledge of Gardners multiple intelligences (1993), Glassers control theory and reality therapy (1986), not to mention learning styles and various gifted and talented theories, to name just a few. The productive pedagogies classroom-coding rubric offers something of an Esperanto6 language that can form a bridge between, and build upon, existing languages. It was developed by the QSRLS research team7 as a classroom observation instrument. However, it has since been widely used by teachers as a framework for facilitating professional dialogue about teaching. It should be treated not as a complete description of quality teaching but as a useful starting point for professional dialogue. In developing the concept of productive pedagogies, the QSRLS extended and re-contextualised in Australia the work of the Centre for Organizational Restructuring (CORS) at the University of Wisconsin in the US. A key concept to emerge out of the CORS research was authentic instruction: learning focused on the construction of knowledge, utilising disciplined inquiry, and with value beyond school. A key claim is that when compared with conventional instruction and conventionally organised schools, authentic instruction and authentically restructured schools demonstrated overall greater rates of achievement, and more equitable achievement among groups of students (Newmann et al., 1996). The potential of authentic instruction to improve the learning outcomes of all students, but especially students from groups with a record of underachievement in schools, was of particular interest to the QSRLS research team. According to the CORS research, authentic instruction is achieved through authentic pedagogy and authentic assessment and is realised through authentic student performance. Instruments representing these three measures developed by CORS were included in expanded coding instruments by the QSRLS (see Table 1). The 20 elements of the Productive Pedagogies Classroom Coding Manual8 were categorised during the course of the study into four dimensions: intellectual quality, recognition of difference, social support and connectedness to the world beyond the classroom. The approach to aligning curriculum, assessment and pedagogy outlined in this paper suggests that not every element of productive pedagogies needs to be present in every class; however, over a unit of work, or say the course of any school day, students should be engaged by a range of best-t pedagogies designed to mediate agreed curriculum and assessment goals. While some pedagogies may lend themselves more readily to certain learning outcomes, these categorisations should not be held too rigidly, since the whole range of productive pedagogies can be utilised across the curriculum. The group of teachers that coded the science and mathematics work samples for the QSRLS

242

D. Hayes

decided to illustrate this point by developing a mathematics task that made heavy use of narrative. Nicola Worth (headteacher, mathematics, Stratheld GHS), Anne Larkin (headteacher, mathematics, Asheld BHS) and Jane Mowbray (Year 6 teacher, Canterbury Public School) chose this element of productive pedagogies because they did not encounter the use of narrative in any of the hundreds of student work samples in mathematics that they coded for the QSRLS. This lesson uses narrative as both a resource and as an expectation of student performance:

Flatland

This is one in a series of lessons in which students are engaged in discovering the properties of 2- and 3-dimensional shapes whilst reading extracts from Flatland which was written by Edwin Abbott in 1884.

Background:

To the inhabitants of space in general in the hope that even as we, the humble natives of Flatland, were initiated into the mysteries of three dimensions having been previously conversant with only two, so too might you the citizens of far wider celestial regions aspire yet higher and higher to the secrets of four, ve or even six dimensions thereby contributing to the enlargement of the human imagination.

Session 1 Introducing Flatland

Outcomes: appreciate that mathematics involves observing, generalising and representing patterns and relationships demonstrate a positive response to the use of mathematics as a tool in practical situations appreciate the importance of visualisation when solving problems use mathematics creatively in expressing new ideas and discoveries

Materials needed Lesson overview

A 2-dimensional shape per student

Issue each student with a 2D shape Ask students to look at their shape and imagine that they are their at shape. Ask them to imagine things such as: moving in a at world what things would look like through their eyes Under the heading: My Life as a (Insert name of shape), ask students to write a brief narrative about their life as a 2-dimensional shape which includes how they move and view things in their world. They could also write about what is easy or difcult in their world. As well as a strong emphasis on narrative, this lesson contains elements of problem solving and students may be engaged in higher-order thinking and substantive conversation while drawing heavily on their background knowledge. In addition, we might expect some elements of productive pedagogies to code highor at least not to code lowin this and every lesson. For example, there is likely to be common agreement

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

243

among teachers and parents that we would like our classrooms to be socially supportive environments that consistently reect a climate of mutual respect and tolerance. Similarly, there is likely to be widespread agreement that it is desirable for students to be actively engaged in lessons. However, most elements of productive pedagogies reect choices made by teachers about the form and content of learning activities. The use of narrative, problem solving and references to metalanguage would be adopted for particular purposes but not necessarily visible in every lesson. Time of day and location within a unit or topic are two of the other factors that teachers may take into consideration when matching pedagogies to purposes in classrooms. The main contribution of productive pedagogies to the process of aligning the message systems of schooling is as a conversational framework for supporting professional dialogue among teachers. It is important to acknowledge that some schools have developed conversational frameworks based on other professional languages, but the core issue is to ensure that teachers have a shared and detailed language for describing and discussing their work.

Conclusion

The illusory and seductive desire to make the world a better place by xing educational problems and dilemmas should not be confused with the day-to-day rhythm of teaching and learning in schools. Sociological research in education over that last thirty years has presented compelling evidence that schools alone are unlikely to compensate for inequities and injustices in society and, more than this, that they play an active role in constituting these divisions even when they are trying to mediate them (Elsworth, 1989). Nevertheless, we do a great injustice to students, teachers and schools if we leave them isolated in their efforts to make learning an effect of schooling. This is the daily challenge of teachers, administrators and a range of other educators. My purpose in this discussion has been to speak to this audience and to lay out a case for prioritising ongoing and sustained dialogue in order to develop a shared understanding of curriculum, assessment and pedagogy and, most importantly, how these may be aligned. I have treaded a tricky path between the neatness and neutrality of survival guides, the consistency and clinical nature of school effectiveness research, and the despair and anger of some sociological analyses. This discussion is offered as a genuine attempt to take seriously the challenge of making learning an effect of schooling.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Stephanie Kingston, Jane Fulcher, Chris Greef, Martin Lauricella, Anne Larkin, Nicola Worth, Jane Mowbray and Margaret Simpson for permission to incorporate their work. I am grateful to my colleagues Martin Mills, Pam Christie and Bob Lingard for their intellectual and social support as we have worked with the data of the QSRLS on numerous related writing projects and presentations. These exchanges have shaped many of the ideas in this paper. The section on assessment is expanded upon in a forthcoming paper with Martin Mills, Bob Lingard and Pam Christie, titled Putting assessment rst: backward mapping from student performance as a foundation for action. Also, thank you to Pam Christie, Stephanie Kingston, Martin Lauricella, Bob Lingard and Maralyn Parker for feedback on drafts.

244

D. Hayes

Correspondence: Debra Hayes, Faculty of Education, University of Technology, Sydney, PO Box 222, Lindeld, New South Wales 2070, Australia. Email: debra.hayes@ uts.edu.au

NOTES

1. The three volumes of this inquiry may be accessed at http://www.pub-ed-inquiry.org 2. By the use of the term rich I am are drawing uponbut not replicatingthe understanding of a rich task within the New Basics curriculum developed by Education Queensland. For further information see http://education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics/html/richtasks/richtasks.html (accessed 6 February 2003). 3. For further information see: http://www.teachers.ash.org.au/sciencelinks/nsw/stages4-5.html (accessed 6 February 2003). 4. For further information about the New Basics Trial: http://education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics/ html/trial/trial.html (accessed 26 March 2003) 5. See http://www.nsn.net.au/index.html (accessed 27 March 2003) 6. An articial universal language. 7. The QSRLS research team consisted of: Joanne Ailwood, Mark Bahr, Ros Capeness, David Chant, Pam Christie, Jenny Gore, Deb Hayes, Jim Ladwig, Bob Lingard, Allan Luke, Martin Mills and Merle Warry. 8. See appendix titled Theoretical rationale for the development of productive pedagogies (Lingard et al., 2001) for a more detailed description of the origin of the elements of this framework.

REFERENCES

ANYON, J. (1995) Race, social class, and educational reform in an inner-city school, Teachers College Record, 97(1), pp. 6994. APPADURAI, A. (1996) Modernity at Large: cultural dimensions of globalization (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press). BALL, S. (1997) Policy sociology and critical social research: a personal review of recent education policy and policy research, British Educational Research Journal, 23(1), pp. 257274. BALL, S.J. (2000) Performativities and fabrications in the education economy: towards the performative state, Australian Educational Researcher, 27(2), pp. 123. BERNSTEIN, B. (1973) Class, Codes and Control (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul). BROWN EASTON, L. (2002) How the Tuning Protocol works, Educational Leadership, March, pp. 2830. CHAPMAN, J. (1996) A new agenda for a new society, in: K. LEITHWOOD (Ed.) International Handbook of Educational Leadership and Administration (Dordrecht and Boston, Kluwer Academic). CHRISTIE, P. (1991) The Right to Learn: the struggle for education in South Africa, 2nd edn (Randburg, South Africa, Sached Trust/Ravan Press). CHRISTIE, P. (2001) Improving school quality in South Africa: a study of schools that have succeeded against the odds, Journal of Education, 26, pp. 4065. CHRISTIE, P. & LINGARD, B. (2001) Capturing complexity. Paper presented to the American Educational Research Association Conference, Seattle, 1014 April. CONNELL, R., ASHENDEN, D.J., KESSLER, S. & DOWSETT, G.W. (1982) Making the Difference: schools, families and social divisions (Sydney, Allen & Unwin). DARLING-HAMMOND, L. (2003) Standards and assessments: where we are and what we need, Teachers College Record, pp. 111, http://www.tcrecord.org (accessed 28 March 2003). DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, TASMANIA (2002) Essential Learning Framework 1 (Hobart). EDUCATION QUEENSLAND (2001) New Basics, http://education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics/ ELMORE, R.F. (19791980) Backward mapping: implementation research and policy decisions, Political Science Quarterly, 94(4), pp. 601616. ELSWORTH, E. (1989) Why doesnt this feel empowering? Working through the repressive myths of critical pedagogy, Harvard Education Review, 59(3), pp. 297324. GARDNER, H. (1993) Multiple Intelligences: the theory into practice (New York, Basic Books) GLASSER, W. (1986) Control Theory in the Classroom (New York, Perennial Library). HARGREAVES, A. (1997) From reform to renewal: a new deal for a new age, in: A. HARGREAVES & R. EVANS (Eds) Beyond Educational Reform: bringing teachers back in (Buckingham, Open University Press). KING, A. (1996a) Reections on one schools efforts to become a learning school, Connections, October, pp. 611.

Making Learning an Effect of Schooling

245

KING, A. (1996b) Learning to learn together: reection on one schools efforts to become a learning school, Reform Agendas Conference: making education work (Ryde, NSW, National Schools Network). LINGARD, B., LADWIG, J. & LUKE, A. (1998) School effects in postmodern conditions, in: R. SLEE, G. WEINER & S. TOMLINSON (Eds) School Effectiveness for Whom? Challenges to the school effectiveness and school improvement movements (London, Falmer Press). LINGARD, B., LADWIG J., MILLS, M., BAHR, M., CHANT, D., WARRY, M., AILWOOD, J., CAPENESS, R., CHRISTIE, P., GORE, J., HAYES, D. & LUKE, A. (2001) The Queensland School Reform Longitudinal Study (Brisbane, Education Queensland). LINGARD, B., HAYES, D. & MILLS, M. (2002) Developments in school-based management: the specic case of Queensland, Australia, Journal of Educational Administration, 40(1), pp. 630. MAHONY, P. & HEXTALL, I. (2000) Reconstructing Teaching: standards, performance and accountability (London, Routledge). MARLAND, M. (1975) The Craft of Classroom Teaching: a survival guide to classroom management in the secondary school (London, Heinemann Educational). MINISTERIAL COUNCIL ON EDUCATION, EMPLOYMENT, TRAINING & YOUTH AFFAIRS (1999) The Adelaide Declaration on National Goals for Schooling in the Twenty-First Century, http://www.curriculum.edu.au/mceetya/ nationalgoals/natgoals.htm (accessed 29 June 2001). NEWMANN, F. & ASSOCIATES (1996) Authentic Achievement: restructuring schools for intellectual quality (San Francisco, Jossey-Bass). SLEE, R., WEINER, G. & TOMLINSON, S (Eds) (1998) School Effectiveness for Whom? Challenges to the school effectiveness and school improvement movements (London and Bristol, PA, Falmer Press). STATE OF QUEENSLAND (2001) New Basicsthe why, what, how and when of Rich Tasks (Brisbane, AccessEd, Education Queensland). TEESE, R. & POLESEL, J. (2003) Undemocratic Schooling: equity and quality in mass secondary education (Carlton, Victoria, Melbourne University Press). THOMSON, P. (2002) Schooling the Rustbelt Kids: making the difference in changing times (Crows Nest, New South Wales, Allen & Unwin). Commentary, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(1), pp. 114. THRUPP, M. (1999) Schools Making a Difference: lets be realistic! School mix, school effectiveness and the limits of social reform (Buckingham, Open University Press). THRUPP, M. (2002) The debate about school effectiveness and improvement: commentary, School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(1), pp. 114. TYLER, R.W. (1949) Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction (Chicago, University of Chicago Press). VINSON, T., ESSON, K. & JOHNSTON, K. (2002) Our Children Our Future. An Inquiry into Public Education in New South Wales. Findings in brief (Sydney, NSW Teachers Federation and the Federation of Parents and Citizens Association NSW). YEATMAN, A. (1993) Corporate managerialism and the shift from the welfare to the competition state, Discourse, 13(2), pp. 39.

Вам также может понравиться

- New Directions For School Effectiveness Research - Muijs 2006Документ20 страницNew Directions For School Effectiveness Research - Muijs 2006PriscillaGalvezОценок пока нет

- How Listening To Students Can Help Schools To Improve: Pedro A. NogueraДокумент8 страницHow Listening To Students Can Help Schools To Improve: Pedro A. Nogueraapi-277958805Оценок пока нет

- Sammons Et - Al (2011) EFFECTIVE SCHOOLS, EQUITY AND TEACHER EFFECTIVENESДокумент18 страницSammons Et - Al (2011) EFFECTIVE SCHOOLS, EQUITY AND TEACHER EFFECTIVENESAlice ChenОценок пока нет

- Professional Learning Communities: A Review of The LiteratureДокумент38 страницProfessional Learning Communities: A Review of The LiteratureidontneedanameОценок пока нет

- Teaching and Learning in the Multigrade ClassroomДокумент18 страницTeaching and Learning in the Multigrade ClassroomMasitah Binti TaibОценок пока нет

- Inclusive 2h2018assessment1 EthansaisДокумент8 страницInclusive 2h2018assessment1 Ethansaisapi-357549157Оценок пока нет

- Whats So Important About Teachers Working ConditionsДокумент17 страницWhats So Important About Teachers Working ConditionsMauricio GutierrezОценок пока нет

- Productive Pedagogies: A Redefined Methodology For Analysing Quality Teacher PracticeДокумент22 страницыProductive Pedagogies: A Redefined Methodology For Analysing Quality Teacher PracticeJanu DoankОценок пока нет

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, & S. Thomas, (2006) Professional Learning Communities A Review of The Literature'Документ39 страницStoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, & S. Thomas, (2006) Professional Learning Communities A Review of The Literature'Abu Jafar Al-IsaaqiОценок пока нет

- A Peer Mentoring ModelДокумент20 страницA Peer Mentoring ModelMaria Rosari AnggunОценок пока нет

- The Relations Between The Institution (School), Teacher and Pupil.Документ5 страницThe Relations Between The Institution (School), Teacher and Pupil.Andrea de SouzaОценок пока нет

- Professional Learning Communities Literature ReviewДокумент39 страницProfessional Learning Communities Literature ReviewAnastasia DMОценок пока нет

- Inquiry EssayДокумент4 страницыInquiry Essayapi-598689165Оценок пока нет

- High School Size Structure and Content What MatterДокумент49 страницHigh School Size Structure and Content What MatterdavidОценок пока нет

- Day (2002) School Reform and Transition in Teacher Professionalism and IdentityДокумент16 страницDay (2002) School Reform and Transition in Teacher Professionalism and Identitykano73100% (1)

- Collaborative Decision-Making and School-Based Management: Challenges, Rhetoric and RealityДокумент24 страницыCollaborative Decision-Making and School-Based Management: Challenges, Rhetoric and RealityJeffrey Ian M. KoОценок пока нет

- Understanding Curriculum As A Polyphonic Text: Curriculum Theorizing in The Midst of StandardizationДокумент16 страницUnderstanding Curriculum As A Polyphonic Text: Curriculum Theorizing in The Midst of StandardizationAdolfoZarateОценок пока нет

- Perspectives on a Century of Math Education ReformДокумент31 страницаPerspectives on a Century of Math Education ReformMaspupahОценок пока нет

- Large ClassesДокумент3 страницыLarge ClassesMaría Fernanda Guzmán GonzálezОценок пока нет

- School RestructuringДокумент16 страницSchool Restructuringtulip432Оценок пока нет

- Achieving Sustainable Systemic Change: An Integrated Model of Educational TransformationДокумент15 страницAchieving Sustainable Systemic Change: An Integrated Model of Educational Transformationd1w2d1w2Оценок пока нет

- School Accreditation and Teacher Empowerment An Alabama CaseДокумент19 страницSchool Accreditation and Teacher Empowerment An Alabama CaseJoy ChristianОценок пока нет

- Transformational Approach and Grade 11 Social StudiesДокумент39 страницTransformational Approach and Grade 11 Social StudiesMichael CatolicoОценок пока нет

- Foundations of Education Course SyllabusДокумент12 страницFoundations of Education Course SyllabusAshish YadavОценок пока нет

- School-Based Management in The OperationДокумент5 страницSchool-Based Management in The OperationJose Francisco50% (2)

- Principles of Effective ChangeДокумент9 страницPrinciples of Effective Changexinghai liuОценок пока нет

- Action Research at The School Level Possibilities and ProblemsДокумент16 страницAction Research at The School Level Possibilities and ProblemsLaura ValeriaОценок пока нет

- Teacher EducationДокумент8 страницTeacher EducationMuhammadYaseenBurdiОценок пока нет

- Curriculm RevisionДокумент17 страницCurriculm RevisionNirupama KsОценок пока нет

- 2003 Sztajn Article Adapting Reform Ideas in DifferentДокумент24 страницы2003 Sztajn Article Adapting Reform Ideas in DifferentALEJO COLOMBO SEREОценок пока нет

- EJ1244634Документ15 страницEJ1244634Yoel Agung budiartoОценок пока нет

- Rosenholtz 1985 Effective SchoolsДокумент38 страницRosenholtz 1985 Effective Schoolslew zhee piangОценок пока нет

- School-Based Management ResearchДокумент24 страницыSchool-Based Management ResearchZainedine ZainОценок пока нет

- The Compliance Tradition and Teachers Instructional Decision Making in A Centralised Education System A Case Study of Junior Secondary GeographyДокумент18 страницThe Compliance Tradition and Teachers Instructional Decision Making in A Centralised Education System A Case Study of Junior Secondary GeographySahmin SaalОценок пока нет

- Teaching and Learning in The Multigrade Classroom: Student Performance and Instructional Routines. ERIC DigestДокумент6 страницTeaching and Learning in The Multigrade Classroom: Student Performance and Instructional Routines. ERIC DigestSer Oca Dumlao LptОценок пока нет

- Preparing teachers to confront neoliberalism and teach equitablyДокумент7 страницPreparing teachers to confront neoliberalism and teach equitablyrcseduОценок пока нет

- The Capacity To Build Organizational Capacity in SchoolsДокумент17 страницThe Capacity To Build Organizational Capacity in Schoolsapi-247542954Оценок пока нет

- Grammarly-PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED BY NEW PRESCHOOL TEACHERS IN SELECTED SCHOOLS OF TACLOBAN CIT1Документ25 страницGrammarly-PROBLEMS ENCOUNTERED BY NEW PRESCHOOL TEACHERS IN SELECTED SCHOOLS OF TACLOBAN CIT1Anonymous cOml7r100% (4)

- Successful Leadership Practices in School Problem-Solving by The Principals of The Secondary Schools in Irbid Educational AreaДокумент13 страницSuccessful Leadership Practices in School Problem-Solving by The Principals of The Secondary Schools in Irbid Educational AreaMarlon Canlas MartinezОценок пока нет

- A Case Study in Leading Schools For Social JusticeДокумент12 страницA Case Study in Leading Schools For Social JusticeRiz GiОценок пока нет

- Chaos Complexity in EducationДокумент18 страницChaos Complexity in EducationEndangОценок пока нет

- Role of The Headteacher in Academic Achievement in Secondary Schools in Vihiga District, KenyaДокумент9 страницRole of The Headteacher in Academic Achievement in Secondary Schools in Vihiga District, Kenyahayazi81Оценок пока нет

- RESEARCH SampleДокумент6 страницRESEARCH SampleCHERRY KRIS PAGMANOJAОценок пока нет

- Culture Change Thai SchlLshpMan2000Документ18 страницCulture Change Thai SchlLshpMan2000david youngОценок пока нет

- OU Resilience 2017 Paper Hilst SmidДокумент19 страницOU Resilience 2017 Paper Hilst SmidGerhard SmidОценок пока нет

- School Community JournalДокумент12 страницSchool Community JournalNadia MNОценок пока нет

- A Critical Examination On Implementing and Establishing A PLC Using Affective ManagementДокумент27 страницA Critical Examination On Implementing and Establishing A PLC Using Affective ManagementGlobal Research and Development ServicesОценок пока нет

- DR - Mahmoud A. Ramadan, Nehad El LeithyДокумент7 страницDR - Mahmoud A. Ramadan, Nehad El LeithyjournalОценок пока нет

- Understanding Language Tests and Testing PracticesДокумент24 страницыUnderstanding Language Tests and Testing Practiceseduardo mackenzieОценок пока нет

- Effects of School Size: A Review of The Literature With RecommendationsДокумент24 страницыEffects of School Size: A Review of The Literature With RecommendationsColby Mark SturgisОценок пока нет

- MSIPsthdbkchapter Oct 05Документ16 страницMSIPsthdbkchapter Oct 05campomaneslove27Оценок пока нет

- Creative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That's Transforming EducationДокумент4 страницыCreative Schools: The Grassroots Revolution That's Transforming EducationMОценок пока нет

- Teachers' Perceptions on School Improvement RoleДокумент12 страницTeachers' Perceptions on School Improvement RoleSayed Muzaffar Shah80% (15)

- Dissertation On Teacher EffectivenessДокумент4 страницыDissertation On Teacher EffectivenessNeedSomeoneToWriteMyPaperForMeUK100% (1)

- Research SampleДокумент51 страницаResearch SampleKim Harold De Paz QuiliopeОценок пока нет

- A Case StudyДокумент9 страницA Case StudydaineОценок пока нет

- Managerial CaracteristictДокумент18 страницManagerial CaracteristictRetnaning TyasОценок пока нет

- Leadership for Success: The Jamaican School ExperienceОт EverandLeadership for Success: The Jamaican School ExperienceDisraeli M. HuttonОценок пока нет

- Reaction Paper On The Story, RICH DAD, POOR DAD Submitted By: IJ L. MADERA Bot Iii-AДокумент2 страницыReaction Paper On The Story, RICH DAD, POOR DAD Submitted By: IJ L. MADERA Bot Iii-AErra Peñaflorida33% (3)

- The Influence of Young Children's Use of Technology On Their Learning: A Review.Документ15 страницThe Influence of Young Children's Use of Technology On Their Learning: A Review.Juliana Moral PereiraОценок пока нет

- Role of Librarian in The 21st Century by SomvirДокумент7 страницRole of Librarian in The 21st Century by SomvirSomvirОценок пока нет

- Repaso Narrative ReportДокумент20 страницRepaso Narrative ReportMarychel MalonesОценок пока нет

- Posters August Format 2Документ16 страницPosters August Format 2juliangrenierОценок пока нет

- P.R.O.P.E.L: Providing Reading Opportunities For Proactive and Engaged LearningДокумент9 страницP.R.O.P.E.L: Providing Reading Opportunities For Proactive and Engaged LearningShareen KayОценок пока нет

- Republic of The Philippine Department of Education Pasig CityДокумент53 страницыRepublic of The Philippine Department of Education Pasig CityMichelle LaurenteОценок пока нет

- Instructional Practices and Students Reading PerformanceДокумент23 страницыInstructional Practices and Students Reading PerformancefaagoldfishОценок пока нет

- 9 Analysis of Teacher Education and Training Programs of Pakistan For ICT-IntegrationДокумент15 страниц9 Analysis of Teacher Education and Training Programs of Pakistan For ICT-Integrationparulian silalahiОценок пока нет

- Personal Qualities for Academic SuccessДокумент10 страницPersonal Qualities for Academic SuccessThe Epic XerneasОценок пока нет

- EDUC 206 Module 7Документ23 страницыEDUC 206 Module 7jade tagab50% (2)

- I, LOUISELY ANAK LORRY, Hereby Declare That I Have Understood and Accepted The Feedback Given by My LecturerДокумент3 страницыI, LOUISELY ANAK LORRY, Hereby Declare That I Have Understood and Accepted The Feedback Given by My LecturerTESLA-0619 Jenny Laleng NehОценок пока нет

- Worksheet 3 Building and Enhancing LiteracyДокумент3 страницыWorksheet 3 Building and Enhancing LiteracyCarlo MagcamitОценок пока нет

- Final Exam GNED 07 (Signed)Документ8 страницFinal Exam GNED 07 (Signed)NEBRIAGA, MARY S. 3-2Оценок пока нет

- Introduction of Woman Role in SocietyДокумент12 страницIntroduction of Woman Role in SocietyApple DogОценок пока нет

- Winnovative PDF Tools Demo: Global Stage Literacy Book 1Документ4 страницыWinnovative PDF Tools Demo: Global Stage Literacy Book 1Inkanata SacОценок пока нет

- Feedback On The 8 Week LRC and Learning Recovery PlanДокумент4 страницыFeedback On The 8 Week LRC and Learning Recovery PlanJessica Nimo0% (1)

- Planning CommentaryДокумент6 страницPlanning Commentaryapi-308664331100% (1)

- The Teaching Profession - M2-Learning-Episode-9Документ19 страницThe Teaching Profession - M2-Learning-Episode-9Aprilyn Balacano Valdez NaniongОценок пока нет