Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Relation of Attachment Style To Family History of Alcoholism and

Загружено:

Loreca1819Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Relation of Attachment Style To Family History of Alcoholism and

Загружено:

Loreca1819Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753

Relation of attachment style to family history of alcoholism and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood

Martha Vungkhanching1 , Kenneth J. Sher , Kristina M. Jackson, Gilbert R. Parra

University of Missouri-Columbia, and the Midwest Alcoholism Research Center, 200 South 7th Street, Columbia, MO 65201, USA Received 31 July 2003; received in revised form 15 January 2004; accepted 29 January 2004

Abstract The present study examined the association between paternal alcoholism and attachment style in early adulthood and sought to determine whether attachment style might, at least partially, mediate intergenerational risk for alcoholism. The current report focuses on the cross-sectional relation between family history (FH) of alcoholism, attachment styles, and alcohol use disorders (AUD) when cohort members were, on average, 29 years old (N = 369; 46% male; 51% FH+). Results indicated that FH+ participants were more likely to have insecure attachment, characterized by fearful-avoidant and dismissed-avoidant styles. Additionally, fearful-avoidant and dismissed-avoidant attachment styles were related to the presence of an AUD even after controlling for sex and FH (P < 0.05). There was little evidence, however, that attachment style mediated the relation between paternal alcoholism and AUD in offspring; the FH-AUD association was only negligibly reduced when the effect of attachment style was controlled. Our ndings suggest that insecure attachment style is a risk factor for AUD, independent of familial risk for alcoholism. 2004 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Attachment; Family; Alcohol; Young adulthood; Children of alcoholics

1. Introduction Extensive research indicates that having an alcoholic parent increases an individuals risk for alcoholism and related problems relative to individuals with no familial alcoholism (Jacob et al., 1999; Sher et al., 1991; Windle, 1996). Twin and adoption studies in both men (see McGue, 1994; Heath, 1995; Heath et al., 1997a) and in women (Heath, 1995; Heath et al., 1997b) provide compelling evidence that genetic factors contribute to alcohol dependence risk but do not explain all of that risk. Further, paternal alcoholism is related to lower quality of familial interactions, characterized by lower rates of problem solving and higher rates of negativity among spouses and adolescent children of alcoholics (COAs) (Jacob and Krahn, 1988; Jacob et al., 1991; Jacob and Leonard, 1988).

Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-573-882-4279; fax: +1-573-884-5588. E-mail addresses: m-vkching@northwestern.edu (M. Vungkhanching), SherK@missouri.edu (K.J. Sher). 1 Present address: Institute for Health Services Research and Policy Studies, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, 339 E. Chicago Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611, USA.

In recent years there has been increasing interest in the role of attachment in adolescent and adult functioning and consideration of attachment theory as one possible framework for understanding interpersonal and emotional outcomes in adult children of alcoholics (El-Guebaly et al., 1993; Jaeger et al., 2000). In this regard, attachment theory is considered to provide an understanding of how the attachment process between a caregiver/parent and child affects a childs early relationships and subsequent relationships in adulthood (Bowlby, 1969, 1973; Hazan and Shaver, 1994; Jaeger et al., 2000). Currently, there is limited work examining the association between adult attachment and alcohol-related problems and no evidence regarding whether attachment style mediates the relation between familial alcoholism and offsprings alcohol dependence risk. 1.1. Attachment style Much of the attachment research on adults has used a strategy developed by Hazan and Shaver (1987, 1990), which is based on Ainsworth et al.s (1978) three patterns of infantcaregiver attachment (secure, anxious-ambivalent and avoidant). Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) extended the concept of Hazan and Shavers (1987) attachment

0376-8716/$ see front matter 2004 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.013

48

M. Vungkhanching et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753

theory to the study of close relationships in adults. They use a four-category prototype measure for romantic attachment styles (RAS) (secure, fearful-avoidant, preoccupied, and dismissed-avoidant), which includes self-report assessment and an interview. Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991) described the secure attachment style in adults as reecting a sense of worthiness and a general perception of people as accepting and responsive. Conversely, the insecure prototypes of attachment style, particularly, the dismissing and fearful styles, both reect the avoidance of intimacy but differ in their need for others acceptance to maintain a positive self-regard. The fearful and preoccupied styles reect strong dependency on others to maintain a positive self-regard. However, they differ in their readiness to become involved in close relationships. For example, the preoccupied individuals reach out to others to fulll their needs to depend on others but the fearful individuals avoid closeness to others for fear of disappointment. Hazan and Shaver (1994) found that adults with insecure (avoidant, anxious-ambivalent) attachment styles reported having experienced parental illness, coldness, rejection, unfairness, and lack of parental support. Securely attached adults are generally characterized as being comfortable with dependency and closeness to others. Conversely, avoidant individuals are uncomfortable with others desires for closeness, and anxious-ambivalent (the preoccupied style in Bartholomew and Horowitzs description) individuals desire a high level of closeness to others but are anxious that others might not want to be close to them (Bawlwin and Fehr, 1995). 1.2. Relation of attachment styles with family history of alcoholism Parental alcoholism tends to disrupt family life in numerous way including nancial loss and vocational instability, marital distress, separation and divorce, impaired parenting, disrupted family rituals, and increased risk for physical, emotional, and sexual abuse (for reviews see Sher et al., 1991; Windle and Searles, 1990). Given the importance of the predictability and stability of family life, in general, and of care-giving gures, in particular, to the development of secure attachment, it is not surprising that attachment-oriented clinicians (e.g., Brown, 1989) have posited severe attachment difculties in the offspring of alcoholics. Brown (1989) posits that the alcoholics needs (for alcohol) preclude his or her availability as a responsive caretaker. Even when there is a nonalcoholic spouse, this spouse is often preoccupied on the needs of the alcoholic that the needs of the child often go unmet. To a large extent, empirical studies tend to bear out the clinical hypothesis that children of alcoholics are at risk for insecure attachment styles. For example, several studies have shown a signicant association between parental heavy drinking and the prevalence of insecure attachment styles in offspring (Brennan et al., 1991; Cavell

et al., 1993; Eiden et al., 2002; El-Guebaly et al., 1993; OConnor et al., 1992). Although these studies convincingly show a relation between parental alcoholism and offspring attachment, the extent that these seeming disruptions in attachment processes are responsible for offspring risk for alcoholism has not been systematically investigated. 1.3. Relation of attachment styles with alcohol abuse/dependence There is good reason to hypothesize that the affective disturbance, impaired sense of self, and impaired self-control associated with insecure attachment styles would be likely to increase risk for alcohol dependence (Carey and Correia, 1997; Johnson et al., 1985; McNally et al., 2003). More specically, insecure attachment may set the stage for two major pathways for the development of alcoholism to take hold: (1) negative affect regulation (i.e., relief drinking or self-medication), and (2) decient socialization and association with deviant peers (see Sher et al., 1991). It is, therefore, not surprising that prior research has demonstrated a positive association between insecure attachment style and heavy drinking in adolescents and adults (Brennan and Shaver, 1995; Cooper et al., 1998; DeFronzo and Pawlak, 1993; El-Guebaly et al., 1993; Jaeger et al., 2000; McNally et al., 2003; Mickelson et al., 1997; Sadava and Pak, 1994). Despite separate literatures relating: (1) parental alcoholism to insecure attachment patterns in offspring, and (2) insecure attachment styles to problematic alcohol involvement, it is not yet known whether attachment style mediates the relation between family history (FH) and offsprings alcohol use disorders (AUDs), that is, whether ones attachment style may explain, at least in part, the familial transmission of alcoholism. The present study sought to examine three interrelated phenomena. First, we examined whether there are differences between COAs and children of nonalcoholics (non-COAs) in their adult attachment styles. Second, we examined the extent to which attachment style was associated with diagnosis of an AUD. Finally, we assessed whether individual differences in attachment style mediate the relation between parental alcoholism and offspring alcoholism.

2. Method 2.1. Participants The current study focused on 369 participants (mean age = 28.9 years, S.D. = 1.0) with complete data on all variables at the Year 11 follow-up of a longitudinal study. The sample was drawn from a total of 410 subjects (84% of the 489 baseline participants targeted for follow-up), from the initial screening sample of 3156 (80% of total class of 3944), rst-time freshman at a large, midwestern university in 1987. A detailed description of participant ascertainment

M. Vungkhanching et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753 Table 1 Frequency distribution of respondents attachment style Attachment style (Year 11) Secure Fearful-avoidant Preoccupied Dismissed-avoidant Inconsistent responders Total n 234 47 18 72 24 395 Total (%) 59.2 11.9 4.6 18.2 6.1 Valid (%) 63.1 12.7 4.8 19.4

49

Note: Participants with missing data at Year 11 were excluded from the analyses. Total percentage includes responders who were inconsistent on their attachment descriptions. Valid percentage excludes the inconsistent responders.

and recruitment is described in Sher et al. (1991). Participants were screened using versions of the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST; Selzer et al., 1975), adapted for rating paternal and maternal drinking problems (F-MAST and M-MAST) (Crews and Sher, 1992) and portions of the Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria interview (FH-RDC; Endicott et al., 1978) that assess paternal and maternal drinking habits. At baseline, participants whose biological fathers met both F-SMAST and FH-RDC criteria for alcoholism were classied as FH+. Individuals whose rst-degree relatives did not meet either F-SMAST or FH-RDC criteria for alcoholism, drug abuse, or antisocial personality disorder, and whose second-degree relatives did not meet FH-RDC criteria for alcohol or drug abuse were classied as FH. The current sample (N = 369) consisted of 202 FH+ (101 females and 101 males) and 167 FH (87 females and 80 males) participants and the sample was predominantly White (93.8%). Individuals with incomplete data on the diagnostic interview or questionnaire batteries at Year 11 were excluded from the study. As such, the total sample with complete data on attachment variables was 395. Participants with inconsistent responses (n = 24) regarding their attachment style (that is, those who endorsed a certain style but whose Likert-type measures indicated another style; see discussion below) were eliminated from further analyses (see Table 1). Of the 371 consistent responders to the attachment style questions, two respondents who were misrepresented on FH status were dropped from further analyses leaving 369 respondents with complete data on all the variables included in these analyses. Marital status of the participants at Year 11 was as follows: 63% married, 5% engaged, 1% separated, 4% divorced, and 27% never married. 2.2. Measures 2.2.1. Attachment styles At Year 11, participants were administered a questionnaire that assessed participants adult attachment styles in romantic relationships, using a four-category attachment measure developed by Bartholomew and Horowitz (1991). Respondents who reported that they had been in at least

one serious relationship were asked to answer the attachment questions with respect to experiences during those relationships. Participants who had not been involved in a serious romantic relationship were asked to imagine what their experiences would be like in such relationships. The questionnaire consists of two parts. First, participants were asked to read the four descriptions of the romantic attachment styles in close relationships, which correspond to the four-category attachment style variable and were asked to rate how self-characteristic each style was on 7-point Likert scale (1: not at all like me, 7: exactly like me). They were then asked to indicate which of the four styles best described them with regard to their behavior in close relationships. The present study adapted a procedure used by Mikulincer and others (see Mikulincer et al., 1990; Mikulincer and Nachshon, 1991) to identify consistent responders. Respondents were categorized as consistent if their attachment style rating was consistent with the one attachment category they chose as most self-descriptive. If respondents highest Likert rating did not match the one attachment variable they chose as most self-descriptive, they were considered inconsistent. For example, if a respondent rated secure highest on the Likert ratings but chose fearful-avoidant or preoccupied as the attachment variable that best described him or her, then he or she would be categorized as inconsistent. A total of 24 respondents, approximately 6% of the sample, were inconsistent (see Table 1, bottom panel) and were removed from further analyses. This percentage of inconsistent responders is similar to those reported in other studies (67% as reported in Mikulincer et al., 1990; Mikulincer and Nachshon, 1991). Sixty-three percent of the participants were classied as secure (n = 234), 13% as fearful-avoidant (n = 47), 5% as preoccupied (n = 18), and 19% as dismissed-avoidant (n = 72) (see Table 1). 2.2.2. Alcohol use disorders The Diagnostic Interview Schedule-Version IV (DIS-IV; Robins et al., 1994) was administered at Year 11 to assess the presence or absence of lifetime alcohol abuse and/or dependence in participants based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Version IV (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Alcohol use disorder was scored if the respondent met criteria for either lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence. 2.3. Data analyses The relation of romantic attachment styles to FH and AUD was examined using 2 -tests of association. Logistic regression was used to examine the romantic attachment style and AUD relation, in which AUD (DSM-IV) was used as the criterion measure and romantic attachment style (dummy coded) as the predictor variables. Prior to considering the associations between RAS and both FH and AUD, we rst examined the association between sex and RAS. Sex was not signicantly related to romantic attachment styles

50 Table 2 Relation of attachment style to sex Attachment style (Year 11) Sex Male n Secure Fearful-avoidant Preoccupied Dismissed-avoidant Total Note: 2 [3, N 97 21 8 42 168

M. Vungkhanching et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753

Female % 57.7 12.5 4.8 25.0 n 13 26 10 30 203 % 67.5 12.8 4.9 14.8

= 369] = 6.39, ns. Sex: 0, male; 1, female.

individuals and 46% were of insecure attachment styles but of the FH participants, 72% reported secure attachment and 28% reported insecure attachment styles (OR = 2.15, 95% CI = [1.39, 3.31]). We also dummy coded specic patterns for comparison: a fearful-avoidant versus the other three attachment categories, and a dismissed-avoidant versus the other three attachment styles. However, neither of these comparisons was signicant (P > 0.05). Thus, we were able to show that FH+ participants were signicantly more likely to report insecure attachment patterns than were FH participants, but we were not able to isolate these differences to specic types of insecure patterns. 3.2. Relation of romantic attachment styles to alcohol use disorder A set of logistic regression analyses examined associations between romantic attachment styles and AUD, controlling for sex. Dummy variables were created to represent the four-category attachment variable with secure attachment as the reference group (i.e., coefcients on the dummy variables represented comparisons of the fearful-avoidant, preoccupied and dismissed-avoidant groups to the secure group). These analyses indicated that individuals with fearful-avoidant (OR = 2.18, 95% CI = [1.15, 4.16], P < 0.05; see Table 4, top panel) and dismissed-avoidant (OR = 2.13, 95% CI = [1.23, 3.68], P < 0.01; see Table 4, top panel) attachment styles were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for lifetime AUD than were those in the secure group. No signicant association was found between preoccupied attachment and AUDs (with secure as the reference group).

(2 [3, N = 369] = 6.39, P > 0.05; see Table 2), but was nevertheless controlled for in all logistic regression analyses to avoid possible confounding. As reported below, additional analyses also controlled for FH when theoretically or empirically justied.

3. Results 3.1. Relation of family history of alcoholism to romantic attachment styles A signicant association between FH and attachment style was noted (2 [3, N = 369] = 12.40, P < 0.01; see Table 3). As can be seen in Table 3, a higher proportion of FH+ participants were in the fearful-avoidant and dismissed-avoidant attachment categories than were FH participants (16% versus 9% and 23% versus 16%, respectively), and a lower proportion of FH+ participants were in the securely attached category relative to FH participants (54% versus 72%, respectively). We conducted additional analyses to verify if the FH+ and FH participants significantly differed in their secure versus insecure attachment style. Our ndings indicated a statistically signicant difference (2 [1, N = 369] = 12.19, P < 0.001) for secure versus insecure (insecure characterized by fearful-avoidant, preoccupied, or dismissed-avoidant) attachment based on FH status (i.e., of the FH+, 54% were securely attached

Table 3 Relation of attachment style to family history of alcoholism (FH) Attachment style (Year 11) Family history of alcoholism FH n Secure Fearful-avoidant Preoccupied Dismissed-avoidant Total 130 17 6 28 181 % 71.8 9.4 3.3 15.5 FH+ n 102 30 12 44 188 % 54.2 16.0 6.4 23.4 Total n 232 47 18 72 369 % 62.9 12.7 4.9 19.5

Table 4 Relation of attachment style to alcohol use disorders (lifetime) based on logistic regression analyses controlling for (1) sex and (2) sex and family history of alcoholism Attachment style (Year 11) AUD (DSM-IV) (Year 11) Odds ratio (1) Entered with sex 2 log likelihood 2 [4, N = 369] = 23.21 Secure vs. fearful-avoidant 2.18 (1.15, Secure vs. preoccupied 1.66 (0.62, Secure vs. dismissed-avoidant 2.13 (1.23, Sex 2.02 (1.31, (2) Entered with sex and FH 2 log likelihood 2 [5, N = 369] = 33.19 Secure vs. fearful-avoidant 1.93 (1.00, Secure vs. preoccupied 1.43 (0.52, Secure vs. dismissed-avoidant 1.92 (1.10, Sex 2.05 (1.32, Family history of alcoholism 2.04 (1.31,

4.16) 4.45) 3.68) 3.11)

5.64 1.03 7.26 10.07

3.73) 3.90) 3.36) 3.19) 3.18)

3.89 0.48 5.23 10.24 9.83

Note: 2 [3, N = 369] = 12.40 (P < 0.01). Family history of alcoholism: 0, FH; 1, FH+.

P < 0.05. P < 0.01. P < 0.001.

M. Vungkhanching et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753

51

In an additional set of analyses, we sought to determine the extent to which attachment styles might mediate the intergenerational transmission of alcoholism using the method described by Baron and Kenny (1986). We rst examined the association between FH and AUD in a simple logistic regression analysis and found that FH+ participants were signicantly more likely to diagnose with a lifetime AUD than were FH participants (2 [1, N = 369] = 13.33, P < 0.001; OR = 2.21, 95% CI = [1.44, 3.39]). Having established this effect and, in prior analysis, the fact that attachment was related to both the predictor (FH) and the outcome (AUD), we then conducted a logistic regression analysis where AUD was predicted from FH and adult attachment styles (dummy coded). The magnitude of the FH-AUD association was only slightly reduced when RAS was entered into the model (OR = 2.04, 95% CI = [1.31, 3.18]; see Table 4, bottom panel), suggesting that RAS likely does not mediate the FH-AUD relation.2

4. Discussion Although both FH+ and FH participants were likely to be securely attached (54% versus 72%), specically in this high functioning sample, family history of alcoholism was found to be signicantly associated with (romantic) attachment style. It is not clear if higher levels of insecure attachment among COAs are causally related to disturbed family interaction patterns that characterize alcoholic families (Eiden et al., 2002; Eiden and Leonard, 1996; Ellis et al., 1997; Jacob and Johnson, 1997; Johnson et al., 1991) or reect inherited temperamental characteristics associated with parental alcoholism (e.g., Sher et al., 1999), or both. The present study provides some evidence for a relation between attachment and alcohol use disorders using DSM-IV criteria in early adulthood. However, it is important to note that this association was evident only for fearful-avoidant and dismissed-avoidant versus securely

2 We also sought to determine if the signicant association between attachment style and FH was due to the shared variance with marital status. We rst examined the relation between FH and marital status (coded as married or engaged participants versus separated, divorced or never married) and found a statistically signicant association between marital status and FH (2 [1, N = 369] = 4.42, P < 0.05). Specically, 73% of the FH participants were either married or engaged compared to 63% of the FH+ participants. A signicant association was also noted between attachment styles (secure versus insecure) and marital status (P < 0.001). Seventy-eight percent of the secure participants were either married or engaged compared to 51% of the insecurely attached participants. Another way of looking at it is that among the married or engaged participants, 72% were securely attached and 28% reported insecure attachment styles. Using logistic regression, we predicted attachment style (secure versus insecure) from FH and found a statistically signicant association (OR = 2.15, 95% CI = [1.39, 3.31], P < 0.001), and this relation was only slightly reduced when we controlled for marital status (OR = 2.00, 95% CI = [1.27, 3.13], P < 0.01). Thus, we can conclude that our FH effect is relatively robust to the effect of marital status.

attached individuals, and no association was found for preoccupied attachment when secure attachment was used as the reference group. These ndings are consistent with other studies that reported that securely attached individuals were less likely to report lower alcohol consumption (Brennan and Shaver, 1995; Cooper et al., 1998; DeFronzo and Pawlak, 1993; El-Guebaly et al., 1993; Jaeger et al., 2000; McNally et al., 2003; Mickelson et al., 1997; Sadava and Pak, 1994). Individuals with insecure attachment styles have been reported to be more likely to use alcohol in order to cope with a troubled relationship (Levitt et al., 1996). Specically, individuals with fearful-avoidant attachment have reported a negative perception of self and others (Bartholomew and Horowitz, 1991). This negative perception might contribute to avoidant individuals vulnerability to the use of alcohol to cope with low self-esteem or distress. Although we found a statistically signicant relation between FH and AUD, this association was only negligibly reduced when the effect of attachment style was controlled. This suggests that romantic attachment style did not mediate the relation between paternal alcoholism and alcohol use disorders in offspring. However, insecurely attached individuals may be at risk for AUD, independent of genetic risk for alcoholism. Although, most measures of behavior and attitudes in adulthood report a strong genetic inuence (OConnor et al., 2000), it is not at all clear that attachment in adulthood is particularly heritable. Livesley et al. (1993), in their study of twins (ranging from 16 to 71 years old), reported that behaviors associated with attachment problems had low heritability. Brussoni et al. (2000), in estimating the heritability of adult attachment based on self-report questionnaires, found some support for additive genetic inuences for secure, fearful, and preoccupied adult attachment styles. However, as our study design is not genetically informative, we cannot assess the relative contribution of genes and environment to adult attachment. Even if adult attachment is strongly heritable, the failure to observe hypothesized mediational relations tends to argue against a genetic correlation between attachment and AUD unlike those observed between AUD and behavioral undercontrol (Slutske et al., 1999, 2002). Rather, it seems that children of alcoholics are at increased risk for attachment difculties from infancy to adulthood but that these effects are not closely coupled with alcoholism risk. Although attachment itself might not be genetic, it might serve to moderate high genetic risk for the development of alcohol use disorders in offspring of alcoholics (Jacob et al., 2003). 4.1. Limitations and future directions Our study is limited in several ways. First, our data are limited to paternal alcohol use disorder, thus limiting our understanding of the unique inuence of maternal alcohol use disorder in the relation between attachment and AUD. This might possibly explain the fact that attachment styles did not mediate the FH-AUD relation, which might be a

52

M. Vungkhanching et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753

function of attachment gure. We assessed history of alcohol use disorders in mothers, but due to the low base rate of maternal alcoholism (n = 20 out of 601), we did not include this variable in the analyses. However, this limits us from determining if the relationship with the nonalcoholic parent may act as a buffer (Werner, 1986). We also attempted to explore if a different measure of attachment style such as Hazan and Shavers three-level attachment style variable might mediate the FH-AUD association.3 Although we observed similar results in our ancillary analyses using the Hazan and Shaver attachment measure (see footnote 2), another measure that more directly assesses parentchild attachment might produce different results. However, the fact that our measure of attachment was related to paternal alcoholism suggests that these measures were clearly relevant to developmental problems in our sample. Second, our study was cross-sectional and we only examined attachment at a single stage of development. Because attachment behavior can vary somewhat over the life span (Bohlin et al., 2000; Vondra et al., 2001; Waters et al., 2000), especially in response to role transitions such as marriage (Crowell et al., 2002; Kirkpatrick and Hazan, 1994), it would be preferable to track attachment stability from infancy and examine its association with familial and extra-familial variables over the course of childhood, adolescent, and adult development. Such a study would permit assessment of those factors that moderate the relation between familial alcohol involvement and attachment, and the extent that attachment difculties are antecedent, consequential, or spuriously related to alcohol use disorders. However, in the absence of life-course data, the current data on young adults still lls an important gap in evaluating the potential mediating role of attachment in the intergenerational transmission of alcohol use disorders. Third, low base rates of participants in the insecure attachment categories (particularly in the fearful-avoidant and preoccupied) reduced our ability to identify specic insecure attachment styles that are most strongly associated with AUD. Larger samples are needed to reliably detect differences among insecure attachment styles. Additionally, limiting our assessments to self-report data taken from participants who had been enrolled in college (albeit high risk) may be biased towards higher functioning individuals, thus limiting us from generalizing the ndings

3 In order to determine if another measure of attachment styles might yield a different result, we examined if Hazan and Shavers three-level attachment category measure might mediate the FH-AUD association. Using similar procedures and analyses as with the four-level attachment variable in analyses utilizing the three-level variable, FH+ participants were signicantly more likely to be diagnosed with an AUD than were FH participants (2 [1, N = 338] = 6.88, P < 0.01; OR = 2.11, 95% CI = [1.20, 3.73]). However, as in the analyses using the four-level attachment variable, we did not nd that the three-level attachment variable signicantly mediated the FH-AUD association. That is, the FH-AUD association was only negligibly reduced when attachment was controlled (OR = 1.92, 95% CI = [1.06, 3.43], P < 0.05).

to the general population. It is also important to note that, as our sample is predominantly Caucasian respondents, we are limited in generalizing our ndings across different ethnic groups. Despite these caveats, attachment style, independent of genetic risk for alcoholism, may be an important factor in understanding alcohol use disorders in early adulthood.

Acknowledgements This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Kenneth J. Sher (R37 AA007231 and R01 AA013987) and Andrew C. Heath (P50 AA11998). The authors wish to thank Jenny M. Larkins for her helpful editorial comments.

References

Ainsworth, M., Blehar, M., Waters, E., Wall, S., 1978. Patterns of Attachment: a Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum, Hilldales, NJ. American Psychiatric Association, 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth ed. Washington, DC. Baron, R., Kenny, D.A., 1986. The moderator-mediator distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 11731182. Bartholomew, K., Horowitz, L.M., 1991. Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 226244. Bawlwin, M.W., Fehr, B., 1995. On the stability of attachment style ratings. Pers. Relat. 2, 247261. Bohlin, G., Hagekull, B., Rydell, A., 2000. Attachment and social functioning: a longitudinal study from infancy to middle childhood. Soc. Dev. 9, 2439. Bowlby, J., 1969. Attachment and Loss: Attachment. Basic Books, New York, NY. Bowlby, J., 1973. Attachment and Loss: Separation, Anxiety and Anger. Basic Books, New York, NY. Brennan, K.A., Shaver, P.R., 1995. Dimensions of adult attachment affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 21, 267283. Brennan, K.A., Shaver, P.R., Tobey, A.E., 1991. Attachment styles, gender and parental problem drinking. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 8, 451466. Brown, S.A., 1989. Life events of adolescents in relation to personal and parental substance abuse. Am. J. Psychol. 146, 484489. Brussoni, M.J., Jang, K.L., Livesley, W.J., MacBeth, T.M., 2000. Genetic and environmental inuences on adult attachment styles. Pers. Relat. 7, 283289. Carey, K.B., Correia, C.J., 1997. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. J. Stud. Alcohol 58, 100105. Cavell, T.A., Jones, D.C., Runyan, D., Constantin-Page, L.P., Velasquez, J.M., 1993. Perceptions of attachment and the adjustment of adolescents with alcoholic fathers. J. Fam. Psychol. 7, 204212. Cooper, M.L., Shaver, P.R., Collins, N.L., 1998. Attachment styles, emotion regulation and adjustment in adolescence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 74, 13801397. Crews, T.M., Sher, K.J., 1992. Using adapted short MASTs for assessing parental alcoholism: reliability and validity. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 16, 576584. Crowell, J.A., Treboux, D., Waters, E., 2002. Stability of attachment representations: the transition to marriage. Dev. Psychol. 38, 467479.

M. Vungkhanching et al. / Drug and Alcohol Dependence 75 (2004) 4753 DeFronzo, J., Pawlak, R., 1993. Effects of social bonds and childhood experiences on alcohol abuse and smoking. J. Soc. Psychol. 133, 635 642. El-Guebaly, N., West, M., Maticka-Tyndale, E., Cohn, D.A., 1993. Attachment among adult children of alcoholics. Addiction 88, 14051411. Eiden, R.D., Edwards, E.P., Leonard, K.E., 2002. Motherinfant and fatherinfant attachment among alcoholic families. Dev. Psychopathol. 14, 253278. Eiden, R.D., Leonard, K.E., 1996. Paternal alcohol use and the motherinfant relationship. Dev. Psychopathol. 8, 307323. Ellis, D.A., Zucker, R.A., Fitzgerald, H.E., 1997. The role of family inuences in development and risk. Alcohol Health Res. World 21, 218226. Endicott, J., Andreasen, N., Spitzer, R.L., 1978. Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC). National Institute of Mental Health, Washington, DC. Hazan, C., Shaver, P.R., 1987. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 511524. Hazan, C., Shaver, P.R., 1990. Love and work: an attachment-theoretical perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 59, 270280. Hazan, C., Shaver, P.R., 1994. Attachment as an organizational framework for research on close relationships. Psychol. Inquiry 5, 122. Heath, A.C., 1995. Genetic inuences on alcoholism risk? A review of adoption and twin studies. Alcohol Health Res. World 19, 166171. Heath, A.C., Slutske, W.S., Madden, P.A.F., 1997a. Gender differences in the genetic contribution to alcoholism risk and to alcohol consumption patterns. In: Wilsnack, R.W., Wilsnack, S.C. (Eds.), Gender and Alcohol. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, pp. 114149. Heath, A.C., Bucholz, K.K., Madden, P.A.F., Dinwiddie, S.H., Slutske, W.S., Beirut, L.J., Statham, D.J., Dunne, M.P., Whiteld, J., Martin, N.G., 1997b. Genetic and environment contributions to alcohol dependence risk in a national twin sample: consistency of ndings in women and men. Psychol. Med. 27, 13811396. Jacob, T., Krahn, G.L., 1988. Marital interactions of alcoholic couples: comparison with depressed and nondepressed couples. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56, 7379. Jacob, T., Krahn, G.L., Leonard, K.E., 1991. Parentchild interactions in families with alcoholic fathers. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 59, 176181. Jacob, T., Leonard, K.E., 1988. Alcoholic-spouse interaction as a function of alcoholism subtype and alcohol consumption interaction. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 97, 231237. Jacob, T., Johnson, S., 1997. Parenting inuences on the development of alcohol abuse and dependence. Alcohol Health Res. World 21, 204 209. Jacob, T., Waterman, B., Heath, A., True, W., Bucholz, K.K., Haber, R., Scherrer, J., Fu, Q., 2003. Genetic and environmental effects on offspring alcoholism: new insights using an offspring-of-twins design. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 60, 12651272. Jacob, T., Windle, M., Seilhamer, R.A., Bost, J., 1999. Adult children of alcoholics: drinking, psychiatric, and psychosocial status. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 13, 321. Jaeger, E., Hahn, N.B., Weinraub, M., 2000. Attachment in adult daughters of alcoholic fathers. Addiction 95, 267276. Johnson, R.C., Schwitters, S.Y., Wilson, J.R., Nagoshi, C.T., McClearn, G.E., 1985. A cross-ethnic comparison of reasons given for using alcohol, not using alcohol or ceasing to use alcohol. J. Stud. Alcohol 46, 283288. Johnson, J., Sher, K., Rolf, J., 1991. Models of vulnerability to psychopathology in children of alcoholics: an overview. Alcohol Health Res. World 15, 3342. Kirkpatrick, L.A., Hazan, C., 1994. Attachment styles and close relationships: a four-year prospective study. Pers. Relat. 1, 123142.

53

Levitt, M.J., Silver, M.E., Franco, N., 1996. Troublesome relationships: a part of human experience. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 12, 523536. Livesley, W.J., Jang, K.L., Jackson, D.N., Vernon, P.A., 1993. Genetic and environmental contributions to dimensions of personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 150, 18261831. McGue, M., 1994. Genes, environment and the etiology of alcoholism. In: Zucker, R., Boyd, G., Howard, J. (Eds.), The Development of Alcohol Problems: Exploring the Biopsychosocial Matrix of Risk. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, pp. 14. McNally, A.M., Palfai, T.P., Levine, R.V., Moore, B.M., 2003. Attachment dimensions and drinking-related problems among young adults: the mediational role of coping motives. Addict. Behav. 28, 1115 1127. Mickelson, K.D., Kessler, R.C., Shaver, P.R., 1997. Adult attachment in a nationally representative sample. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 73, 10921106. Mikulincer, M., Florian, V., Tolmacz, R., 1990. Attachment styles and fear of personal death: a case study of affect regulation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 58, 273280. Mikulincer, M., Nachshon, O., 1991. Attachment styles and patterns of self-disclosure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 61, 321331. OConnor, M.J., Sigman, M., Kasari, C., 1992. Attachment behavior of infants exposed prenatally to alcohol: mediating effects of infant affect and motherinfant interaction. Dev. Psychopathol. 4, 243256. OConnor, T.G., Croft, C., Steele, H., 2000. The contributions of behavioural genetic studies to attachment theory. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2, 107122. Robins, L.N., Cottler, L., Bucholz, K.K., Compton, W., 1994. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV. Public Health Service, Washington, DC. Sadava, S.W., Pak, A.W., 1994. Problem drinking and close relationships during the third decade of life. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 8, 251258. Selzer, M., Vinokur, A., van Rooijen, L., 1975. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST). J. Abnorm. Psychol. 91, 350357. Sher, K.J., Trull, T.J., Bartholow, B.D., Veith, A., 1999. Personality and alcoholism: issues, methods and etiological processes. In: Blane, H., Leonard, K. (Eds.), Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism, second ed. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 54105. Sher, K.J., Walitzer, K.S., Wood, P.K., Brent, E.E., 1991. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 100, 427448. Slutske, W.S., Heath, A.C., Madden, P.A.F., Bucholz, K.K., Statham, D.J., Martin, N.G., 2002. Personality and the genetic risk for alcohol dependence. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 111, 124133. Slutske, W.S., True, W.R., Scherrer, J.F., Heath, A.C., Bucholz, K.K., Eisen, S.A., Goldberg, J., Lyons, M.J., Tsuang, M.T., 1999. The heritability of alcoholism symptoms: indicators of genetic and environmental inuence in alcohol-dependent individuals, revisited. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 23, 759769. Vondra, J.I., Shaw, D.S., Swearingen, L., Cohen, M., Owens, E.B., 2001. Attachment stability and emotional and behavioral regulation from infancy to preschool age. Dev. Psychopathol. 13, 1333. Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., Albersheim, L., 2000. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: a twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Dev. 71, 684689. Werner, E., 1986. Resilient offspring of alcoholics: a longitudinal study from birth to age 18. J. Stud. Alcohol 47, 3440. Windle, M., 1996. On the discriminative validity of a family history of problem drinking index with a national sample of young adults. J. Stud. Alcohol 57, 378386. Windle, M., Searles, J.S. (Eds.), 1990. Children of Alcoholics: Critical Perspectives. Guilford Press, New York.

Вам также может понравиться

- Parent Attachment, Childrearing Behavior, and Child Attachment Mediated EffectsДокумент10 страницParent Attachment, Childrearing Behavior, and Child Attachment Mediated EffectsLoreca1819Оценок пока нет

- Manyu MasterThesis ETD 5th RevisionДокумент49 страницManyu MasterThesis ETD 5th RevisionLoreca1819Оценок пока нет

- Attachment With Parents and Peers in Late AdolescenceДокумент13 страницAttachment With Parents and Peers in Late AdolescenceLoreca1819Оценок пока нет

- Identity in University Students The Role of Parental and RomanticДокумент10 страницIdentity in University Students The Role of Parental and RomanticLoreca1819Оценок пока нет

- Attachment and Self-Evaluation in Chinese AdolescentsДокумент20 страницAttachment and Self-Evaluation in Chinese AdolescentsLoreca1819Оценок пока нет

- Aristotel Despre SufletДокумент55 страницAristotel Despre SufletLoreca1819Оценок пока нет

- Forensic PsychologyДокумент8 страницForensic PsychologyKanwal EnarayОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Reading Comprehension WorksheetsДокумент16 страницReading Comprehension WorksheetsAndrea LeeОценок пока нет

- ItДокумент3 страницыIt?????Оценок пока нет

- PembunuhanPembunuhan Massal Yang Terjadi Di IndonesiaДокумент127 страницPembunuhanPembunuhan Massal Yang Terjadi Di IndonesiabunjurОценок пока нет

- DEMANDT, Alexander. (2013) Zeitenwende. Aufsätze Zur Spätantike, Cap.08Документ15 страницDEMANDT, Alexander. (2013) Zeitenwende. Aufsätze Zur Spätantike, Cap.08Juan Manuel PanОценок пока нет

- Sec 2 History Common TestДокумент6 страницSec 2 History Common Testopin74Оценок пока нет

- Justice Hardwick, Re Paynter v. School District No. 61, 09-23Документ48 страницJustice Hardwick, Re Paynter v. School District No. 61, 09-23Jimmy ThomsonОценок пока нет

- Case DigestДокумент4 страницыCase DigestRussel SirotОценок пока нет

- Anoja WeerasingheДокумент10 страницAnoja WeerasinghePrasanna RameswaranОценок пока нет

- Masterfile Vs Eastern Memorials/Delgallo Studio: ComplaintДокумент8 страницMasterfile Vs Eastern Memorials/Delgallo Studio: ComplaintExtortionLetterInfo.comОценок пока нет

- Piracy at SeaДокумент10 страницPiracy at SeaAlejandro CampomarОценок пока нет

- Assignment April 7 2021Документ5 страницAssignment April 7 2021esmeralda de guzmanОценок пока нет

- EEOC v. AbercrombieДокумент2 страницыEEOC v. Abercrombiefjl_302711Оценок пока нет

- Contract 2Документ9 страницContract 2ANADI SONIОценок пока нет

- Afp Mutual Benefit Vs CAДокумент1 страницаAfp Mutual Benefit Vs CAcarlo_tabangcuraОценок пока нет

- Family Law Assignment 1Документ13 страницFamily Law Assignment 1Rishab ChoudharyОценок пока нет

- Manzano vs. PerezДокумент5 страницManzano vs. PerezaudreyracelaОценок пока нет

- General Exceptions CrimeДокумент18 страницGeneral Exceptions CrimeAIMLAB BROОценок пока нет

- Rekap Obat LasaДокумент8 страницRekap Obat LasaYENNYОценок пока нет

- Thayer, The Quad and Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated FishingДокумент4 страницыThayer, The Quad and Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated FishingCarlyle Alan ThayerОценок пока нет

- Sf2 2019 Grade 7 Year I HonestyДокумент6 страницSf2 2019 Grade 7 Year I HonestyDaniel ManuelОценок пока нет

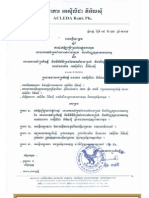

- Acleda Bank Aml 2009Документ60 страницAcleda Bank Aml 2009Jeevann Goldee Shikamaru100% (1)

- RoSD Heroic Abilities and SpellsДокумент2 страницыRoSD Heroic Abilities and SpellsJLDCОценок пока нет

- Joint Counter AffidavitДокумент4 страницыJoint Counter AffidavitRoy HirangОценок пока нет

- Hide and Seek Questions 2Документ2 страницыHide and Seek Questions 2s23158.xuОценок пока нет

- Chord Maroon 5Документ3 страницыChord Maroon 5SilviDavidОценок пока нет

- Quaid-e-Azam Wanted Pakistan To Be Islamic Welfare State'Документ2 страницыQuaid-e-Azam Wanted Pakistan To Be Islamic Welfare State'Zain Ul AbidinОценок пока нет

- STD Facts - Syphilis (Detailed)Документ4 страницыSTD Facts - Syphilis (Detailed)Dorothy Pearl Loyola PalabricaОценок пока нет

- Alcantara Vs NidoДокумент7 страницAlcantara Vs Nidobhieng062002Оценок пока нет

- Christopher Booker's Seven Basic PlotsДокумент8 страницChristopher Booker's Seven Basic PlotsDavid RuauneОценок пока нет

- Five Year LLB Course of Nuals Assignment TopicsДокумент3 страницыFive Year LLB Course of Nuals Assignment TopicsYedu KrishnaОценок пока нет