Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nevada Reports 1910-1911 (33 Nev.) PDF

Загружено:

thadzigsОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nevada Reports 1910-1911 (33 Nev.) PDF

Загружено:

thadzigsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

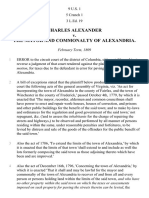

33 Nev.

17, 17 (1910)

REPORTS OF CASES

DETERMINED IN

THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE

STATE OF NEVADA

____________

July Term, 1910

____________

33 Nev. 17, 17 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

[No. 1885]

THERESA BARNES, Respondent, v. CITY OF

CARSON, Appellant.

1. Municipal CorporationsExcavations in StreetsLiability of City.

In an action against a city for personal injuries resulting from plaintiff's falling into

an excavation made in a street, although the act of incorporation of the city may have

given to the city trustees exclusive power to regulate its streets, drains, etc., yet where it

appeared that for some years the city had paid the bills which were approved by the city

trustees for street work done by the city marshal and had permitted him to do such

work, it must be presumed that it authorized him to make the excavation in question

rendering the city liable for his negligence.

Appeal from District Court of the First Judicial District of the State of Nevada, Ormsby

County; John S. Orr, Judge, presiding.

Action for personal injuries by Theresa Barnes against the City of Carson. Judgment for

plaintiff, and defendant appeals. Affirmed.

The facts sufficiently appear in the opinion.

33 Nev. 17, 18 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

Roberts & Sanford and Summerfield & Curler (Robert Richards, of counsel), for

Appellant:

Conceding, for the time being only, that it was the legal duty of the city to repair and

maintain the sidewalk or culvert in question, yet, if the court should hold, as we believe it

will, that the acts of Mr. Kinney and Mr. Lafreniere were ultra vires in the premises, and that

therefore the doctrine of respondeat superior cannot be made to apply, the defendant is not

liable to the plaintiff, and upon the record the case must be reversed, for the following

reasons:

FirstThe plaintiff will then be bound in law by her pleading, and the gist of the cause of

action must then be based upon the omission by the city to perform a legal duty, whereas the

gist of the action as laid in the complaint is based upon the alleged performance of a lawful

act in an unlawful manner; and

SecondThe plaintiff will then be bound in law by the evidence, or, rather, the absence of

evidence, in the case, in this: There is no evidence in the record showing or tending to show

in the least that the defendant had any knowledge or notice, either actual or constructive, of

the condition of the sidewalk or culvert, or of the existence of the excavation into which

plaintiff fell.

So, therefore, if Mr. Kinney and Mr. Lafreniere were acting ultra vires, or the city is not

responsible for their acts, as we will hereinafter show, the city is not liable to plaintiff under

the condition of the record as it exists in this court, for the element of defendant's negligence

will be absent both in pleading and proof; and as was said in Arndt v. City of Cullman, 132

Ala. 520, 90 Am. St. Rep. 925: It was incumbent on plaintiff in order to maintain the action

to aver and prove express notice of the alleged defect in the sewer, or facts from which it

might be inferred that the corporate authorities were properly chargeable with constructive

notice thereof.

In Smith v. Mayor, 66 N. Y. 295, 23 Am. Rep. 53, this language is used: There was no

evidence and there is no finding that the sewer was liable to become obstructed under

ordinary circumstances, so as to require the watch and care of the officials to prevent it

becoming filled and choked with the wash of the street, or that it had been obstructed for

any time and under circumstances from which it might be assumed that the officers of the

city did know or ought to have known the fact.

33 Nev. 17, 19 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

under ordinary circumstances, so as to require the watch and care of the officials to prevent it

becoming filled and choked with the wash of the street, or that it had been obstructed for any

time and under circumstances from which it might be assumed that the officers of the city did

know or ought to have known the fact. The city does not insure the citizen against damage

from the works of its construction, but is only liable, as other proprietors, for negligence or

wilful misconduct. The principles upon which municipal corporations are held liable for

damages occasioned by defects in streets and sewers and other public works are well settled

by numerous cases, and the liability is made to rest, in any case, upon some neglect or

omission of duty (Barton v. Syracuse, 37 Barb. 292, 36 N. Y. 54; Griffin v. Mayor of New

York, 5 Seld. 456; McCarthy v. Syracuse, 46 N. Y. 194; Nims v. Troy, 59 N. Y. 500), and the

judgment must be affirmed.

It is stated in City v. Weger, 66 Pac. 1070: Appellee had judgment against appellant for

damages on account of injuries sustained by a fall on a defective crosswalk in the city of

Boulder. The defect was a board about eight inches wide missing from a wooden crosswalk.

To justify affirming this judgment the evidence must show that the city had knowledge,

either actual or constructive, of the existence of the defect, and had not exercised proper

diligence in its repair.' (City of Denver v. Moewes, 60 Pac. 986.) It must appear that

defendant had notice of such obstruction, or that it had existed for such a length of time as to

impart notice, and that defendant had not used reasonable diligence in removing such

obstruction.' (City of Boulder v. Niles, 9 Colo. 415, 12 Pac. 632.)

See, also, Lewisville v. Batson, 29 Ind. App. 21, 63 N. E. 861; and Thompson's Com. Law

of Neg. vol. 5, sec. 6170, which lays down the rule that a municipality is not liable for

injuries caused by unguarded obstructions placed on its sidewalks by third persons, without

authority, unless it has either actual or constructive notice thereof.

We come now to the errors appearing in the record urged on this appeal.

33 Nev. 17, 20 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

We contend that from the facts in the case the defendant is not liable to the plaintiff for the

injuries sustained.

This proposition is reserved in the transcript in divers forms, namely, first, in the motion

for a nonsuit and the exception to the denial thereof; second, in the notice of intention to

move for a new trial upon the grounds therein specified; and, third, in the specific assignment

of errors relied upon by the defendant; in consequence of which, we urge:

FirstThat the evidence is insufficient to justify the verdict and judgment, and that the

same are against law; and

SecondThat the verdict of the jury and the judgment of the court are not supported by

the evidence and are contrary to the same.

We are well aware that the appellate court is not called upon to consider the weight of the

evidence when there is any evidence to support the verdict, and that it will not disturb the

verdict where there is a conflict of evidence, as these are matters for the lower court; but the

rule is otherwise where there is no evidence to support the verdict, and then it is the duty of

the appellate tribunal to reverse the case, and grant a new trial.

The undisputed facts appearing from the evidence, in so far as they relate to the powers

and duties of the city marshal or his employees, are that Mr. Kinney at the time of the

accident occurring to plaintiff, and prior and subsequent thereto, was the duly elected,

qualified and acting sheriff of Ormsby County, and by virtue of that office and deriving his

authority therefrom, he was the ex officio city marshal of Carson City, and on that date, and

prior and subsequent thereto, Mr. Lafreniere was hired and employed by him to work upon

the streets of the city in repairing breaks and culverts and on work required to be done upon

the streets and alleys of the defendant; that Mr. Kinney delegated the authority to Mr.

Lafreniere, and that neither the city council of Carson, nor the city, nor any of its officers,

ever had any control or direction of the duties of Mr.

33 Nev. 17, 21 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

control or direction of the duties of Mr. Kinney or Mr. Lafreniere, or ever undertook such

control or direction.

Such being the testimony of Mr. Kinney and Mr. Lafreniere in that regard, it becomes

necessary to examine the statute and amendments thereto incorporating the city, and the

ordinances thereunder, admitted in evidence, and to ascertain therefrom to what extent the

powers and duties of the city marshal and his employees have been defined. The statute and

amendments referred to are the following: An act entitled An act to incorporate Carson

City, approved February 25, 1875 (Stats. 1875, p. 87), the act amendatory thereof, approved

March 2, 1877 (Stats. 1877, p. 117), the act amendatory thereof, approved March 5, 1879

(Stats. 1879, p. 67), and the act amendatory thereof, approved March 6, 1889 (Stats. 1889, p.

68).

The only reference to the city marshal and his employees, or to their powers and duties, are

the following:

From the Act of 1875: Sec. 10. The board of trustees shall have the power:

FourteenthTo cause the city marshal to appoint one or such number of policemen, as

they shall from time to time determine, who shall be under the direction and control of the

city marshal.

Sec. 14. The sheriff of Ormsby County shall, in addition to the duties now imposed upon

him by law, act as the marshal of the city, and shall be ex officio city marshal.

Sec. 27. The city marshal, in addition to the general duties of his office, shall execute all

process issuing from the recorder's court, act with full powers as a policeman, and as chief of

all the police force appointed for the city as such, and shall collect all taxes upon city licenses.

In his absence the under sheriff shall act as city marshal.

Sec. 30. The powers and duties of the city marshal may be more fully defined by such

ordinances as shall not be inconsistent with this act.

33 Nev. 17, 22 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

From the Acts of 1877, 1879 and 1889: Sec. 10. The board of trustees shall have the

following powers:

To cause the city marshal to appoint one or such number of policemen as the board of

trustees shall from time to time determine, who shall be under the direction and control of the

marshal, as head of the police force of said city; but such appointment shall have no validity

whatever until the same shall have been approved by said board of trustees; and said board of

trustees shall have power to remove any such policemen from office, at pleasure, upon good

cause shown, and, upon a charge being preferred, to suspend until the same shall have been

passed upon finally.

It is evident, therefore, that under the act incorporating the city, and the amendments

thereto, the duties of the city marshal are merely the general duties of a peace officer, and that

the organic law of the municipal corporation gives him no authority or power to superintend

or repair streets, or bind the city, by contract or otherwise, in any matter whatsoever; and he

can have no general power or authority, and certainly none beyond the scope of his duties as a

peace officer, for the unanswerable reason, if for no others, that, as aforesaid, it is provided by

section 30 of the act that the powers and duties of the city marshal may be more fully

defined by such ordinances as shall not be inconsistent with this act. In the absence of a

more full definition of his powers and duties, he is limited by the express provisions of the act

and its amendments, and when he exceeds the authority granted him thereunder, as he has

done in this case, he does not act even colori officii, but is a common tort feasor, and the city

does not assume any responsibility, and cannot be bound, for any injuries sustained while he

so acts.

The question then presents itself: Has the board of trustees by the ordinances admitted in

evidence made such a more full definition of the powers and duties of the city marshal, and if

so, is the same applicable to the facts of this case? This question cannot be better answered

than by quoting these ordinances in extenso.

33 Nev. 17, 23 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

Ordinance No. 5

The Board of Trustees of Carson City do ordain:

Section 1. No person or business firm shall place or cause to be placed upon any street,

sidewalk, square or thoroughfare, any box, bale, lumber or any other thing, of any nature

whatsoever, so far as to obstruct the same, excepting only for the display of goods, wares and

merchandise; provided, that any person erecting or repairing any building may occupy and

use the sidewalk and one-third of the street in front thereof for such time as is necessary for

the depositing of material required for the construction or repair thereof; and provided

further, that for the purpose of displaying goods, wares and merchandise, two feet in width,

commencing at the front line of the lot, may be used; provided, that a space of six feet in

width shall at all times be kept clear for the accommodation of persons passing; and provided

further, that merchants and others receiving and delivering goods shall be allowed six hours

from the time they are deposited until they are removed.

Sec. 2. Any person by whom or under whose direction or authority any portion of a public

street, alley or sidewalk may be made dangerous, shall erect, and so long as the danger may

continue, maintain around the portion of the street, alley or sidewalk so made dangerous, a

good and substantial barrier, and shall cause to be maintained during the night, from sunset

till daylight, a lighted lantern at both ends of such portion of the street, alley or sidewalk so

made dangerous.

Sec. 3. No person shall in any manner or for any purpose break up, dig up, disturb,

undermine or dig under, or cause to be dug up, broken up, disturbed, undermined or dug

under, any public street, highway or place, or fill in, put, place thereon, or deposit in or upon

any public street, highway or place, any earth, sand, dirt, clay, manure or rock, without the

permission of the board of trustees being first had and obtained.

Sec. 4. Any person who shall violate any of the provisions of this ordinance shall be

deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof, shall be fined in any sum,

not less than five dollars nor more than two hundred dollars, or be imprisoned in the

county jail not more than two nor more than one hundred days, or be both so fined and

imprisoned."

33 Nev. 17, 24 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

demeanor, and upon conviction thereof, shall be fined in any sum, not less than five dollars

nor more than two hundred dollars, or be imprisoned in the county jail not more than two nor

more than one hundred days, or be both so fined and imprisoned.

Ordinance No. 30.

The Board of Trustees of Carson City do ordain:

Section 1. Ordinance No. 23, providing for a special policeman for Chinatown, etc.,

adopted June 7, 1875, is hereby repealed.

Sec. 2. This ordinance shall take effect on and after the first day of April, 1876.

Ordinance No. 31.

The Board of Trustees of Carson City do ordain:

Section 1. All owners of buildings and lots, or either, fronting to the west, on the east line

of Carson Street, between Washington Street and Sixth Street, shall lay down, within sixty

days after the passage of this ordinance, a good and substantial sidewalk in front of their said

property. Said sidewalks shall be ten feet wide at all places, and of uniform grade in each

block, as nearly as practicable. All sidewalks now laid down, within the limits hereinabove

described, which do not conform to the above-named requirements, must be made to conform

thereto within the above required time.

Sec. 2. All owners of buildings or lots, or either, in said city, fronting to the east, on the

west line of Carson Street, between Washington Street and Sixth Street, shall lay down,

within sixty days after the passage of this ordinance, a good and substantial sidewalk in front

of their said property. Said sidewalks shall not be less than eleven and three-quarters nor over

twelve feet wide at all places, and of uniform grade in each block, as nearly as practicable. All

sidewalks now laid down within the limits in this section specified, which do not conform to

the hereinabove specified requirements, must be made to conform thereto within sixty days

after the passage of this ordinance.

33 Nev. 17, 25 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

Sec. 3. Sleepers used in laying down sidewalks required by this ordinance shall not be

less than three by six inches in size, of sound material, well placed, not more than three feet

apart, and firmly supported; and the planking used thereon shall not be less than eleven and

three-quarters nor over twelve feet long, on the west side, and ten feet long on the east side of

said street, not less than two inches thick, not more than six inches wide, of sound material

evenly laid, and thoroughly spiked to the sleepers. Awning posts on all sidewalks shall be

placed within three inches of the outer edge thereof, and shall be thoroughly spiked and

secured at base and crown.

Sec. 4. Brick or stone may be used, if of suitable quality, in laying down sidewalks, but

must be made to lie evenly, and of width and grade as hereinabove specified.

Sec. 5. Sidewalks in said city shall be kept in good condition by the owners of the

property in front of which they are, at their own expense, and such owners shall be liable to

the city, and to any injured party, for all damages arising from failure so to keep sidewalks in

good condition for safe use thereof, as above required.

Sec. 6. For the purpose of carrying out and enforcing the foregoing provisions of this

ordinance, the city marshal is hereby made inspector of sidewalks in said city, and it shall be

his duty as such inspector, subject to the board of trustees of said city, to see that suitable and

proper material be used, sleepers laid at proper distances from each other, and placed

securely, the required size of sleeper and plank used, the prescribed width and grade observed

in laying said sidewalks, and that the provisions of this ordinance be in all respects carried

out. In the discharge of said duties, said inspector shall have the power and privilege to call to

his assistance such aid as he may need, in the way of experts, for whose services, when

rendered, the city shall pay a reasonable compensation.

Sec. 7. If any owner of any house or lot, or either, within the limits defined by this

ordinance, shall fail to lay down a sidewalk in front thereof, or to make the sidewalk, if any,

already laid down in front thereof, conform to the requirements of this ordinance, within

the time herein specified the city marshal shall, unless otherwise directed by the board of

city trustees, lay down such sidewalk, or cause that already laid down to conform to the

requirements of this ordinance without delay, and the necessary expense of so doing shall

be a lien upon the house and lot, or either, in front of which sidewalk shall be so laid

down, or made to conform to the requirements of this ordinance;

33 Nev. 17, 26 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

if any, already laid down in front thereof, conform to the requirements of this ordinance,

within the time herein specified the city marshal shall, unless otherwise directed by the board

of city trustees, lay down such sidewalk, or cause that already laid down to conform to the

requirements of this ordinance without delay, and the necessary expense of so doing shall be

a lien upon the house and lot, or either, in front of which sidewalk shall be so laid down, or

made to conform to the requirements of this ordinance; and the same shall be recovered by

action of said city against said property, and the owner or owners thereof, in any court of

competent jurisdiction.

The contention of appellant, that these ordinances do not define the powers and duties of

the city marshal so as to make them applicable to the case at bar, could, with propriety, be

considered in conjunction with the contention hereinafter made that the lower court erred in

admitting these ordinances in evidence over objection; and should this tribunal hold that these

ordinances do not make any such definition of the powers and duties of the city marshal, then

it follows as a logical sequence that the objection of the defendant to their introduction taken

at the trial should have been sustained. So, in determining this latter contention, our views in

this part of the brief presented are urged as additional reasons why this court should hold, as

hereinafter maintained, that the lower court erred in admitting these ordinances in evidence,

and that such ruling constitutes reversible error.

We can relegate Ordinance No. 30 from this discussion without comment, as it can throw

no light upon the subject whatever; and Ordinance No. 5 requires but short consideration.

This ordinance is general in its terms and penal in its entirety. Section 1 thereof prohibits the

obstruction of streets and sidewalks by merchants and other persons, and gives those erecting

or repairing buildings the privilege of using a designated portion of the street and sidewalk

for the deposit of necessary material thereon. Section 2 thereof requires any person, by whom

or under whom a street or sidewalk is obstructed, to guard the same with suitable barriers,

and to place at the same lighted lanterns during the night, while such obstruction

continues.

33 Nev. 17, 27 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

the same with suitable barriers, and to place at the same lighted lanterns during the night,

while such obstruction continues. Section 3 thereof prohibits the digging or disturbing of any

street, highway or place, or placing or depositing thereon earth, sand, rocks or dirt, without

the permission of the board of trustees; and section 4 thereof prescribes a penalty for the

violation of the ordinance.

Surely, it cannot be said that this ordinance defines the powers and duties of the city

marshal in any respect whatsoever, and its competency, relevancy and materiality as a feature

in the case cannot be urged with any force or success. If the action were a personal action

against Mr. Kinney, or Mr. Lafreniere, to recover damages for the action laid in the

complaint, it might well be said that their violation of this ordinance might be an element

tending to fix the amount of their liability to the plaintiff. If the plaintiff can recover in this

case, it is only under the doctrine of respondeat superior, and this ordinance cannot tend to

establish the relation of principal and agent or of master and servant, between the city on the

one side and Mr. Kinney and Mr. Lafreniere on the other, in any degree whatever. Hence,

Ordinance No. 5 is also eliminated from the case.

There only remains, then, Ordinance No. 31 under which to define the powers and duties

of the city marshal as applicable to the case at bar, but for that purpose it can afford no aid.

This ordinance contains seven sections, and is entitled An ordinance in relation to

sidewalks. Sections 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 thereof have no bearing upon the question here involved,

as they appertain exclusively to sidewalks for Carson Street, between Washington and Sixth

Streets, in the city, section 7 thereof particularly providing that if any owner of any house or

lot, or either, within the limits defined by this ordinance, i. e., Carson Street between

Washington and Sixth Streets in the city, shall fail to lay down a sidewalk, etc., and

continuing by providing certain duties of the city marshal in that event, and certain

consequences to the property and the owners thereof within said limit.

33 Nev. 17, 28 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

Since none of the sections named can be construed to control or even appertain to the work at

the corner of Curry and Telegraph Streets, Carson City, where the injuries were sustained by

plaintiff, it is expedient to analyze sections 5 and 6 of this ordinance. These, by no

intendment, nor by any rule of statutory construction, can be held to define the powers and

duties of the city marshal to any extent other than to inspect the kind and grade of material to

be used in sidewalks, and the detailed methods in the construction thereof as prescribed in the

ordinance, and certainly not to the extent of requiring or even permitting the city marshal

without let or hindrance to lay, or construct, or repair sidewalks throughout the city.

By section 5 of the ordinance the duty is imposed upon property owners to keep their

sidewalks in good condition, and for failure so to do, they are made liable in damages, and by

section 6 thereof it is provided that for the purpose of carrying out and enforcing the

foregoing provisions of this ordinance, the city marshal is hereby made inspector of sidewalks

in said city; and it shall be his duty, as such inspector, subject to the board of trustees of said

city, to see that suitable and proper material be used; sleepers laid at proper distances from

each other, and placed securely; the required size of sleepers and planks used; the prescribed

width and grade observed in laying said sidewalks, and that the provisions of this ordinance

be in all respects carried out. In the discharge of said duties, said inspector shall have the

power and privilege to call to his assistance such aid as he may need, in the way of experts,

for whose services, when rendered, the city shall pay a reasonable compensation.

It appears from this last section that each duty of the city marshal in relation to sidewalks

is specifically enumerated, and no duty omitted can be regarded as included therein, but, by

operation of law, it must be held to be excluded therefrom under the well-settled rule:

inclusio unius, exclusio alterius. Moreover, the phrases in the latter part of the section,

namely, in the discharge of said duties, i. e., duties elsewhere above enumerated, and, in

the way of experts, import and imply that the powers conferred and the duties imposed

by that section are merely such that permit and require the city marshal to inspect the

kind and grade of material and the detailed methods of construction as prescribed in the

ordinance, and certainly not to permit or require him to construct or repair sidewalks

throughout the city, as aforesaid.

33 Nev. 17, 29 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

latter part of the section, namely, in the discharge of said duties, i. e., duties elsewhere above

enumerated, and, in the way of experts, import and imply that the powers conferred and the

duties imposed by that section are merely such that permit and require the city marshal to

inspect the kind and grade of material and the detailed methods of construction as prescribed

in the ordinance, and certainly not to permit or require him to construct or repair sidewalks

throughout the city, as aforesaid.

However, let the interpretation of this ordinance be as it may, it relates simply and

exclusively to sidewalks, and we are concerned here with a flooded sewer, drain or ditch, and

the excavation therefrom made to repair the same. No matter what powers can be said to have

been conferred or duties imposed by the ordinance upon the city marshal, relating to

sidewalks, those powers and duties cannot be extended to include the performance of the

work alleged in the complaint by the city marshal or by those whom he should employ for

that purpose.

It is apparent, we think, that whether the excavation in question be regarded as a repair to a

sidewalk, or a repair to a drain, ditch or sewer, no power was conferred, or duty imposed,

either upon Mr. Kinney, as city marshal, or upon Mr. Lafreniere, employed by him, by

statutory enactment, city ordinance, or by direction of the executive officers of the

municipality, and without such authority, and the direction and control of the work

undertaken by Mr. Kinney and Mr. Lafreniere, as appears from the evidence here, the doctrine

of respondeat superior cannot be made to apply, and the city is not liable for the injuries

sustained, for their acts in the premises were ultra vires, which made them common tort

feasors, and for which they alone are responsible in damages to the plaintiff. (28 Cyc. pp.

1274, 1276, 1278; 20 Am. & Eng. Ency. Law, pp. 1199, 1200, 1201, 1202.)

It was said in McDonough v. Mayor, 6 Nev. 95: It is manifest from what is said that the

plaintiff must allege and prove that the street where the injuries resulted was opened by the

city, and that the pitch or defect was made by it, or that it was left in that condition when

the street was opened.

33 Nev. 17, 30 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

made by it, or that it was left in that condition when the street was opened. These facts are not

alleged in the complaint, nor were they proven at the trial. The judgment must be reversed.

A case very similar to the facts presented on this appeal was decided by the Supreme Court

of Maine in 1902, being entitled Bowden v. The City of Rockland, and reported in 11 Am.

Neg. Rep. 429, et seq. It appeared there that a wall along a public highway proved insufficient

and collapsed, and it became necessary to build a new wall to make the highway safe, within

the statute. To do this required the wall to be built partly, at least, upon land outside of the

limits of the highway, and accordingly the owners of the land and the quarry sent to the city

counsel a written license to build and maintain such a wall, and to take the materials from the

quarry. The street railway also using the highway stipulated with the city in writing to bear

part of the expense. The city engineer made a plan for the work, and undertook the building

of the wall in accordance therewith, and during the course of construction thereof a boom

slipped and plaintiff was injured, for which he sought to mulct the city in damages upon the

ground that the slipping of the boom and his consequent injury resulted from the negligence

of the street commissioner in setting up the derrick, and that in setting up the derrick the

street commissioner was the agent of the city and was not then acting as a public officer in the

performance of official duty. The court said:

Rebuilding the retaining wall on a larger scale than the old (that being necessary to make

the way safe and convenient) was clearly within the statutory powers of the street

commissioner, at least after the city had provided funds and a place therefor. It is well settled,

by decisions too numerous and familiar to require citation, that a highway surveyor or street

commissioner in repairing ways is, and acts as, a public officer, and the municipality, within

whose limits he acts and which appointed him and furnished him funds for the work, is not

liable for his torts, unless it has interfered and itself assumed control and direction of the

work, and of the surveyor or commissioner.

33 Nev. 17, 31 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

for his torts, unless it has interfered and itself assumed control and direction of the work, and

of the surveyor or commissioner. Has the city thus interfered and assumed control and

direction in this case? is the pivotal question.

While some persons, probably city officers, in behalf of the city, procured the written

license of the quarry owners, and also a stipulation from the street railway company to bear

part of the expense of rebuilding the wall, it does not appear that the city council ever passed

a vote in the matter. No directions appear to have been given by vote of the city council, or

the committee on streets, to the city engineer to prepare plans. So far as appears, he did so suo

motu, as part of his regular work, or at the request of some officers. The plaintiff, however,

claims that the mayor and one or more of the committee on streets gave the street

commissioner orders to build the wall, and that he acted under those orders, and not under his

statutory authority. We do not think that plaintiff's own evidence shows so much. There

appears to have been some question in the mind of the street commissioner as to his authority

to build the wall as street commissioner, in view of all the circumstances. He consulted the

mayor, the city solicitor, and members of the committee on streets, and they assured him that

he had the authority as street commissioner, and told him to go ahead and build the wall. He

then proceeded with the work as above described.

It must be apparent that this is not enough to show that the city assumed the control and

direction of the work and of the commissioner, reducing him from a public officer to a mere

employee of the city. At most the various officials with whom he talked merely assured the

commissioner that he had authority and the duty to build the wall, and told him to go ahead

and exert his authority, and to do his duty, and it would be all right.' This case is more within

Barney v. City of Lowell, 98 Mass. 570, and Prince v. City of Lynn, 149 Mass. 193, 21 N. E.

296, in which cases the city was held not liable for the negligence of the street

commissioner, though he was acting under the city charter.

33 Nev. 17, 32 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

gence of the street commissioner, though he was acting under the city charter.

That the city obtained the license from the quarry owners to use their land and materials

was not a usurpation of the street commissioner's authority, and did not oust him from the

control and direction of the work of rebuilding, no more than if the city had condemned the

land and material. The arrangement for the street railroad company to bear part of the

expenses had no effect upon the status of the street commissioner, no more than arrangement

to raise the money by loan or tax. That the plan for the wall was made by a city employee (the

city engineer) did not make the city the owner or director of the work.

We do not say that if the mayor, city solicitor, or members of the committee on streets, or

all combined, acting of their own volition, without vote of the council, had specifically

assumed control and direction of the work and of the commissioner, such act of theirs would

have made the commissioner a mere agent of the city, and the city his principal, answerable

for his torts. It was said in Woodcock v. City of Calais, 66 Me. 234, on page 236, citing

Haskell v. City of Bedford, 108 Mass. 208, that the orders which the street commissioner may

have received from the mayor or city solicitor could not affect his relative status to the city,

and could not bind the city in respect to the commissioner's acts. In Goddard v. Inhabitants of

Harpswell, 88 Me. 238, 33 Atl. 980, it was held that the selectmen, without vote of the town

authorizing it, could not make themselves agents of the town in matters of highways.

In this case it is enough to say that the evidence does not show that the city, through the

action of any legally constituted authority, had so far assumed control and direction of the

work of rebuilding the wall, and of the street commissioner, as to make his negligence in

setting up the derrick the negligence of the city.

The facts of the case at bar are even stronger in appellant's favor than those appearing in

the foregoing decision.

33 Nev. 17, 33 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

lant's favor than those appearing in the foregoing decision. There the city authorities did take

some active interest, if not an active part, in the work in hand, to the extent that the city

engineer prepared the plans, the license from the quarry owners inured to the benefit of the

municipality, and the executive officers thereof were consulted about the work, and at least

verbally sanctioned it, yet such things done on behalf of the city did not establish in law that

the city had, or had assumed, any authority, control or direction over the rebuilding of the

wall or over the street commissioner; while it appears from the record on this appeal that the

city neither expressly nor impliedly, nor did any of its executive officers, authorize, direct or

control any of the acts of the city marshal or any of his employees in any matter whatever; but

on the contrary it affirmatively appears that neither Mr. Kinney nor Mr. Lafreniere was

empowered or obligated, by statute, ordinance, resolution or verbal direction of or on behalf

of the defendant, to make the excavation in question, or to repair the drain, ditch, sewer or

sidewalk mentioned in the complaint; and that Mr. Kinney assumed exclusive jurisdiction

over that character of work, but under what designation or grant of power he did so it does

not appear, and it cannot be ascertained; and that he employed whomsoever he saw fit, and

did not suffer the city, nor any of its officers, to direct or control him in the least.

As has been well said in the case of Hilsdorf v. City of St. Louis, 45 Mo. 95, 100 Am. Dec.

352: The rule that prescribes the responsibility of principals, whether private persons or

corporations, for the acts of others is based upon their power of control. If the master cannot

command the servant, the acts of the servant are clearly not his. He is not master, for the

relation implied by that term is one of power, of command; and if a principal cannot control

his agent, he is not an agent, but holds some other additional relation. In neither case can the

maxim, respondeat superior, apply to them, for there is no superior to respond."

33 Nev. 17, 34 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

is no superior to respond. While we have made this excerpt from this case, as we deem it in

point, we will further discuss this decision.

It appears from the opinion that the stables of the St. Louis Railroad Company were

consumed by fire, and one hundred and forty mules therein destroyed, and their carcasses left

more or less burned. The weather was warm, and, obviously, it became necessary to remove

them at once. The city had previously legislated concerning the removal of carcasses, and

pursuant to such legislation had granted the exclusive privilege to certain designated persons,

which privilege was in force at the time of the fire. On the morning of the loss by the railroad

company the clerk of the board of health received the proper notice from the company under

the ordinance, and one Settle, employed by those who had the privilege, appeared on the

scene for the purpose of removing the carcasses, and there met the mayor of the city. On

account of the distance it was at once apparent that the removal could not be made to the

usual place, and that Settle had no means of consummating the removal, and informed the

mayor that it would take him a week to do the whole job. The mayor then obtained a

proposition from him to throw them into the river at a designated place for a specified price

per head, which was communicated to the railroad company, which afterwards paid the

aggregate amount. The carcasses, having been dumped into the river, the current did not

strike them as supposed, and they sank into plaintiff's quarry; on which account he was

denied the use thereof, and prosecuted an action for damages against the city of St. Louis and

the railroad company. The court said:

The defendants made separate defenses, and after the evidence was submitted, counsel for

the city asked the court to instruct the jury that, on the facts proved, the plaintiff could not

recover against it. This instruction the court refused to give, and thus the question is raised

whether, under the facts claimed to be proved by the plaintiff, the city is liable to him for the

damage arising from the acts of Settle.

33 Nev. 17, 35 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

from the acts of Settle. If the city is thus liable, the liability arises by virtue of its relation to

the mayor and to Settle, or to one of them. The responsibility of an employer for those in his

service depends upon the character of their acts, and especially upon their relation to the

service. It would not be right to charge him for the torts of his servant that had no relation to

his employment. The contract of service is no guaranty of general good conduct as a citizen,

but any act done in pursuance of the contract of hire will in general charge the principal as

well as the agent or servant. Corporations, whether municipal or aggregate, are now held to

the same liability as individuals, and will not be permitted to screen themselves behind the

plea that they are impersonal, and their acts are but the acts of individuals; and if an agent or

servant of a corporation, in the line of his employment, shall be guilty of negligence and

commit a wrong, the corporation is responsible in damages.

In the case at bar, the mayor, it appears, acted with zeal and energy to save the public

from the effects of the terrible nuisance upon the premises of the railroad company. But he

cannot be said to have been acting upon behalf of the city, but rather as a good citizen, whose

other heavy responsibilities were a spur to look after the public welfare generally. The general

duty of abating nuisances is imposed by article 1 of said ordinance 4894, especially by

sections 6 and 7, upon the board of health, and the street inspectors under its direction, and it

does not appear that the mayor has anything to do with the matter. The matter did not come

before the board of health, nor does it appear that the mayor undertook to bind the city, or that

he acted officially in the premises. But if he did, he went beyond his authority as mayor, and

his acts were not those of the city. (Thayer v. Boston, 19 Pick. 511, 31 Am. Dec. 157.)

The suggestion that Settle did not remove these carcasses under this contract of his

employers, but by special direction of the mayor, only brings us back to the first proposition,

that the mayor had no authority to give any such direction, nor does it appear that he acted

officially, but, as we shall presently see, effected between Settle and the railroad

company an arrangement for their removal.

33 Nev. 17, 36 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

such direction, nor does it appear that he acted officially, but, as we shall presently see,

effected between Settle and the railroad company an arrangement for their removal.

The judgment, being against both the city and the railroad company, when it should have

been against the railroad company alone, is reversed and the cause remanded.

As, from the record here, it appears that the power over drains, ditches, sewers, sidewalks

and culverts, is reserved by law to the board of trustees of the city of Carson, and that the city

marshal usurped the functions of that board in making the alleged repairs, and as it nowhere

appears that the board had any knowledge of the condition of the drain, sidewalk, ditch, sewer

or culvert, or of the excavation, mentioned in the complaint, we believe that the rules laid

down in the case last quoted from are strongly applicable for a proper determination of this

appeal, and, paraphrasing an expression in that decision contained, we declare with

confidence that the matter of those repairs did not come before the board of trustees, nor does

it appear that the city marshal undertook to bind the city, or that he acted officially in the

premises. But if he did, he went beyond his authority as city marshal, and his acts were not

those of the city. (19 Pick. 511; 31 Am. Dec. 157.)

The rule is thus stated in Caspary v. The City of Portland, 20 Am. St. Rep. 845: It will

thus be seen that, on general principles, it is necessary, in order to make a municipal

corporation impliedly liable, on the maximum of respondeat superior, for the wrongful acts

or negligence of an officer, that it be shown that the officer was its officer, either generally or

as respects the particular wrong complained of, and not an independent public officer; and

also that the wrong was done by such officer while in the legitimate exercise of some duty of

a corporate nature which was devolved upon him by law, or by the direction or authority of

the corporation. (2 Dillon on Municipal Corporations, sec. 974.)

33 Nev. 17, 37 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

As was said in Gould v. City of Topeka, 4 Pac. 828; Courts should not allow any but the

most formal evidence to be introduced to prove that the city authorities had planned, or

ordered or ratified, any such dangerous place within their streets. Courts should not presume

without formal proof that the governing board of a city had deliberately done wrong.

There was no evidence showing that the city, by its council or otherwise, had ever

expressly planned or ordered that the street where plaintiff's injuries occurred should be made

or left in the condition in which it then existed; and the evidence does not show that the city,

by its council or otherwise, ever expressly ratified any such condition of the street. The only

evidence upon this subject was that the street had remained in that condition for some years,

and that the mayor and two members of the city council had knowledge of its condition. The

judgment of the court below will be reversed, and the cause remanded for a new trial.

It is with some degree of confidence that we bring this topic of our brief to a close. There

is no evidence of essential elements in the case to enforce liability against the defendant in

this appeal. We have established that unless the city itself undertook the work, or duly

authorized it, or that it was done by the city marshal empowered by either statutory

enactment, municipal ordinance, or express authority, control and direction of the executive

officers of the defendant, the plaintiff cannot recover in the action. It is evident, from the

discussion we have made, that the city did not undertake, nor authorize, the work, and that the

city marshal was not empowered as aforesaid, or at all, but acted in the premises, under

supposed legal right, no doubt, yet, of his own volition, unauthorized, undirected and

uncontrolled. Applying the law to this situation, as it is, and as we have laid it down, the

evidence is insufficient to support the verdict, and the motions for nonsuit and for a new trial

should have been granted, as of course.

In conclusion, without further quotation or argument, we cite: Kansas City v. Brady, 34

Pac. SS4; Sievers v. San Francisco, 47 Pac. 6S7; Mitchell v. Rockland, 41 Me.

33 Nev. 17, 38 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

we cite: Kansas City v. Brady, 34 Pac. 884; Sievers v. San Francisco, 47 Pac. 687; Mitchell

v. Rockland, 41 Me. 363, 68 Am. Dec. 252; Thayer v. Boston, 19 Pick. 511, 31 Am. Dec.

157; Hilsdorf v. City of St. Louis, supra, 100 Am. Dec. 352, and the extended monographic

note following the opinion; Goddard v. Inhabitants, 30 Am. St. Rep. 373, and the extended

monographic note following the opinion; Barrows on Negligence, secs. 180, 181.

Leaving the proposition last presented, we now contend that the lower court erred in

admitting in evidence over defendant's objections Ordinances Nos. 5, 30, and 31. The

objections to their introduction and the exceptions reserved to their admission are very

specific, when it would have been sufficient to have stated that each of those ordinances was

incompetent, irrelevant and immaterial. Hence, it is unnecessary here to incorporate such

objections and exceptions.

If the reason or motive for the introduction of the ordinances on behalf of plaintiff were

desired, it could be readily ascertained by a mere reference to the transcript. It will be noted

that only after the motion for a nonsuit was argued, submitted and denied, then, under leave

of court, the plaintiff reopened her case, and over objection introduced the ordinances in

question. It evidently appealed to plaintiff that the denial of that motion afforded no security,

in that a material and essential element in her proof was lacking, namely, the power and

duties of the city marshal in the premises, and though there was, and could be, no proof to

supply that element, yet it was incumbent upon her, at least, to attempt to supply the same,

and in making that attempt she caused these ordinances to be introduced in evidence.

However, we have shown hereinabove that the ordinances referred to confer no power and

impose no duty upon the city marshal or his employees in relation to the repairs mentioned in

the complaint, and therefore they and each of them are irrelevant, incompetent and

immaterial, and the court erred in permitting their introduction. But it might be urged that this

error was harmless, to which we reply that it was manifestly prejudicial, since thereby the

plaintiff was permitted to attempt to prove to the satisfaction of the jury an essential

element of her case, and especially since no other evidence was or could be adduced by

her to establish that element, namely, the power and duty of the city marshal and his

employees, if any they had, in relation to the work or repairs upon the drain, ditch, sewer,

sidewalk or culvert, referred to in the complaint.

33 Nev. 17, 39 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

that it was manifestly prejudicial, since thereby the plaintiff was permitted to attempt to prove

to the satisfaction of the jury an essential element of her case, and especially since no other

evidence was or could be adduced by her to establish that element, namely, the power and

duty of the city marshal and his employees, if any they had, in relation to the work or repairs

upon the drain, ditch, sewer, sidewalk or culvert, referred to in the complaint. The error of

admitting these ordinances in evidence is plain, and that it was highly prejudicial is

self-evident.

See the case of Stebbins v. Mayer, 16 Pac. 745.

At the request of the plaintiff the court gave to the jury Instruction No. 1, to which

defendant excepted, and which said instruction is as follows: You are instructed that the

fundamental principle of the law of damages is that the person injured in his person or

property rights shall receive compensation therefor, for which the person injured, if

reasonable care and prudence were observed, is entitled to compensation to the full amount of

the injury suffered. We contend that the giving of this instruction was prejudicial error.

Taking this instruction as an abstract proposition of law, a mere reading of it convinces that it

is incorrect. Its incorrectness is plain from its incompleteness; and when it is sought to apply

such an instruction to a concrete case, especially to the case at bar, where no defense was

made as to the nature and extent of plaintiff's injuries, or to the condition of the place where

the same occurred, the incorrectness of that instruction was doubly apparent.

By so instructing the jury, it was in effect telling the members thereof that, from the mere

fact that plaintiff was injured by falling into an excavation on a public street, that therefore

she was entitled to recover damages against the city. The jurors' minds were thereby

distracted from the question as to whether the city was negligent, and even from the question

as to whether the injury was caused by plaintiff's negligence, and their minds were thereby

solely centered upon the one question, namely, the injury itself, and the nature and extent

thereof.

33 Nev. 17, 40 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

thereof. Such an instruction, without the qualifications here mentioned contained therein, is

wrong in theory and vicious in practice.

Samuel Platt and Alfred Chartz, for Respondent.

By the Court, Sweeney, J.:

Respondent obtained a judgment against the appellant in the sum of $5,000 for personal

injuries on account of falling into an excavation made in one of the public streets of the city

of Carson, which excavation was alleged to have been made by the appellant and negligently

left unprotected. From the judgment, and from an order denying the defendant's motion for a

new trial, defendant has appealed.

It is the main contention of appellant that the proofs failed to show that the excavation was

made under the authority of the city trustees, or that they, with knowledge, ratified the acts of

the persons who performed the work. It is the contention of appellant that the evidence

shows, without conflict, that the work was done under the direction of the city marshal acting

independently of the city trustees, and that there was no proof that he was authorized by the

said city trustees to perform such work, nor was his act ratified by said trustees with

knowledge of the circumstances. It is further contended upon the part of the appellant that the

said city marshal, by virtue of his office, had no power to make the excavation, nor did he

possess, by virtue of his office, any supervision over the streets and alleys of the city of

Carson.

Section 10 of the act incorporating the city of Carson (Stats. 1875, c. 43, as amended by

Stats. 1907, c. 29) provides The board of trustees shall have the following powers: * * * 3.

To lay out, extend or change the streets and alleys in said city and provide for the grading,

draining, cleaning, widening, lighting or otherwise improving the same; also to provide for

the construction, repair, preservation, grade and width of sidewalks, bridges, drains and

sewers and for the prevention and removal of obstructions from the streets, alleys and

sidewalks, drains and sewers of said city.

33 Nev. 17, 41 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

obstructions from the streets, alleys and sidewalks, drains and sewers of said city. * * *

It may be conceded, under this provision of the statute, that the control of the streets,

sidewalks, and alleys of Carson City is exclusively in the hands of the city trustees, and that

the city marshal, by virtue of his office, has no power or control over the same. Whatever acts

the city marshal may perform in relation to the streets, sidewalks, and alleys of the city must

be by virtue of authority from the city trustees, or else they are, in law, but the mere acts of a

stranger.

The excavation in question was made by one A. Lafreniere, who testified that he was

employed by and acting under the general direction of the city marshal. The said Lafreniere

testified that he had been in the employ of the city marshal for about four years prior to the

accident in question, and that he was paid for his services by the city. It also appears from the

record that the said Lafreniere was the man generally in charge of the street work for the city.

While Mr. Lafreniere testified that he was employed by and acting under the direction of the

city marshal in the matter of looking after the streets and alleys of the city, and while the

marshal's testimony was to the same effect, it can hardly be said, we think, that both the city

marshal and Mr. Lafreniere were not working under the direct authority of the city trustees.

All claims for services rendered were approved by the city trustees and paid by the city, and

this condition of affairs is shown by the record to have existed for at least four years prior to

the accident in question. It cannot be said, we think, that a long-continued arrangement of this

kind was not without the authority and approval of the city trustees who alone had legal

authority in the premises. Had the proofs shown that the city marshal and the witness

Lafreniere had assumed to act only in the particular case which resulted in the injury to the

plaintiff and respondent, it might well be contended that the city would not be bound by their

acts unless by proof of special directions in this particular case or by subsequent ratification

with full knowledge of all the facts.

33 Nev. 17, 42 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

particular case or by subsequent ratification with full knowledge of all the facts. Where it

appears conclusively, however, that the work done upon the streets, which occasioned the

accident, was in pursuance of a policy in reference to such streets that had existed for a

number of years, it must be presumed that such policy was with the approval of the lawfully

constituted authority.

However, whatever question there may be as to whether the work in question was done by

lawful authority or was subsequently ratified, the same, we think, is removed from question

in the case by the pleadings themselves. The answer of the defendant, appellant herein, sets

up the following: For a third, other, and affirmative answer and defense to plaintiff's

complaint, defendant alleges and shows to the court as follows, to wit: That at the time

mentioned in plaintiff's complaint, to wit, the 24th day of January, 1906, and for several days

immediately prior thereto, a violent storm and precipitation of water occurred in Carson City

and the vicinity thereof, necessitating defendant, by and through its employees, in different

places to temporarily open drains and ditches in order to allow the flood waters to pass

therethrough, and that because of said necessity defendant did on the said 24th day of

January, A. D. 1906, at the place mentioned in plaintiff's complaint, partly open the plank

covering of a drain ditch, and did temporarily remove therefrom accumulated debris and dirt

for the purpose of allowing said flood waters to pass through, but that said act or acts of the

defendant were rendered necessary by reason of the extraordinary and unusual conditions

herein mentioned, and that said removal and deposit of said materials was temporary and was

performed and caused to be performed by defendant in as reasonable and safe a manner as

said existing conditions permitted.

From this alleged appellant's defense, it appears that the city authorities knew, prior to the

accident, that a condition existed making it necessary to make repairs in the street at the place

where the accident occurred, and that it did make the excavation which occasioned the

accident and resulting injury to the plaintiff, for which a judgment for damages was

recovered in this case.

33 Nev. 17, 43 (1910) Barnes v. City of Carson

that it did make the excavation which occasioned the accident and resulting injury to the

plaintiff, for which a judgment for damages was recovered in this case. There is here a clear

admission in the appellant's answer of the only fact that has been argued upon the appeal as

being unsupported by the evidence. The evidence is without contradiction that the excavation

was left in the evening without lights to warn pedestrians of its existence and that, by reason

of such negligence, the injury in question occurred. No question is presented upon the appeal

that the damages were excessive.

Error is assigned in the admission of certain city ordinances over defendant's objection and

in the giving of one instruction to the jury, but in the view we take of this case, even

conceding, without so deciding, that the lower court erred in the admission of the ordinances

or in the giving of the instruction, the same were without prejudice. When it was established

upon the trial that the excavation was made in the street by the city and negligently left in the

nighttime without proper lights to indicate the same, and that by reason thereof the plaintiff

was injured, there was nothing left for the court and jury to determine but the amount of

damages. As the other alleged errors did not go to the question of the amount of damages, the

alleged errors, if any occurred, could not possibly have been prejudicial, hence we have given

them no consideration whatever.

The judgment and order of the lower court are affirmed.

____________

33 Nev. 44, 44 (1910) McKim v. District Court

[No. 1911]

SMITH H. McKIM, Petitioner, v. THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE SECOND JUDICIAL

DISTRICT OF THE STATE OF NEVADA, IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF

WASHOE, and the HON. W. H. A. PIKE, One of the Judges of said Court, and W. A.

FOGG, Clerk of said Court, Respondents.

1. PleadingPlea in AbatementAnswer.

Under civil practice act, sec. 39 (Comp. Laws, 3133), providing that the only pleadings on the part of

the defendant shall be a demurrer or an answer, and section 44 (section 3139) providing that when any of

the matters enumerated in section 40 (section 3135) as grounds of demurrer do not appear on the face of

the complaint, the objection may be taken by answer, matters in abatement or bar can only be set up in

the answer.

2. TrialPreliminary QuestionsDetermination.

Where the answer raises a question preliminary to the right of the court to determine the merits, it is

proper for the court to first determine such matter before considering issues going to the merits.

3. DivorceDetermination as to JurisdictionMode of Review.

The question raised by defendant in divorce as to the sufficiency of the evidence to establish

residence on the part of the complainant can be reviewed only by appeal, and not by original proceedings

in the supreme court, seeking to obtain an order requiring the judge of the trial court to show cause why

defendant in the divorce should not be permitted to file his plea in abatement.

Original proceeding. In the matter of Smith H. McKim against the District Court of the

Second Judicial District of the State of Nevada, and others. On a petition praying that

respondents be required to permit petitioner to file a certain plea in abatement. Dismissed.

The facts sufficiently appear in the opinion.

James Glynn, for Petitioner:

I. Jurisdiction of subject of action may be challenged at any time by court of its own

motion, by defendant or by stranger to suit.

II. When lack of jurisdiction appears upon face of record, challenge may be by motion to

dismiss or by demurrer.

33 Nev. 44, 45 (1910) McKim v. District Court

record, challenge may be by motion to dismiss or by demurrer.

III. When such lack of jurisdiction does not appear of record, it can be reached before

joinder of issue only by plea in abatement. (Gregg v. Sumner, 21 Ill. App. 110.)

IV. The question of jurisdiction of subject-matter of action is quite apart from the

meritsespecially in a divorce action under our statute. Facts constituting jurisdictional

prerequisites may be traversed without considering facts plead as cause of action, and, if

traversed in advance of issue upon merits, should be determined before issue as a matter of

justice to the court as well as the defendant. If traverse is predicated upon what appears of

record, courts never refuse to consider by motion to dismiss. How much more should they do

so if showing be made of an attempt to impose upon the court's jurisdiction by false

allegations of jurisdictional prerequisites. (Sommers v. Sommers (divorce case), 16 Bradwell

(Ill. App.) 76.)

V. Residence, which signifies such bona fide residence as amounts to legal domicile, is a

jurisdictional prerequisite under Comp. Laws, 502, and failing to appear action should be

dismissed. If made to falsely appear, it becomes an attempted fraud upon the courtand that

fact should be permitted to be shown before issue, to the double end that (1) the court may

prevent the imposition, and (2) the defendant may be spared the manifest injustice of being

required to proceed to a hearing that will represent much of annoyance, loss of time and

expense which can never be included in a cost bill.

VI. Divorce proceedings are recognized as being sui generis. This is especially true under

statutes like ours, providing for a purely conditional jurisdiction (Comp. Laws, 502) and a

special method of service upon nonresidents (Comp. Laws, 503). A clear recognition of this

is to be found in the holding of this court to the effect that the law of marriage and divorce,

as administered by the ecclesiastical courts, is a part of the common law of this country,

except as it has been altered by statute."

33 Nev. 44, 46 (1910) McKim v. District Court

country, except as it has been altered by statute. (Wuest v. Wuest, 17 Nev. 217.)

VII. A plea in abatement is the recognized method of disclosing a lack of jurisdiction of

the subject of the action, and that before joinder of issue. (Coonis Com. Co. v. Block, 130 Mo.

668; Welling v. Beers, 120 Mass. 548; Livingston v. Story, 11 Pet. 392; Ency. Pl. & Pr. p. 4;

Winter v. Union Pkg. Co., 93 Pac. 930; Wells v. Patton, 50 Kan. 732; Bailey v. Schrader, 34

Black (Ind.) 260; Sutherland Code P. & P., vol. 1, secs. 460-559; Hoppwood v. Patterson, 2

Or. 50; Or. Cent. Ry. v. Wait, 3 Or. 428; Fairbanks v. Woodhouse, 6 Cal. 434; Small v.

Gwinn, 34 Cal. 676; Preston v. Culbertson, 58 Cal. 198.)

VIII. A resort to a plea in abatement for the purpose of disclosing lack of jurisdictional

prerequisites in advance of issue is authorized by Comp. Laws, 3095, in that it is neither

repugnant to nor in conflict with the general provisions of the practice act, for the reason that

they leave us provisionless in such an exigency.

IX. But if some latitude were needed to permit the resort to a plea in abatement in such

case, by reason of the provisions of the practice act as to pleadings, it should certainly be

found to be authorized by Comp. Laws, 506, by the terms of which it is most manifest that

the legislature recognized that with this sui generis class of actions the proceedings,

pleadings and practice could not be expected to conform exactly to the general rules

governing ordinary actions.

X. Moreover, the concluding clause of the section (Comp. Laws, 506): But all

preliminary and final orders may be in such form as will best effect the object of this act, and

produce substantial justice, clearly contemplates all needed latitude in respect to the

determination of so important a preliminary question as the existence of the prescribed

statutory jurisdictional prerequisites.

XI. The substantial justice which is to be conserved under the provisions of Comp.

Laws, 506, will not permit the status of the defendant to be lost sight of. He is shown to be a

resident of the State of New York, where the facts alleged in the complaint do not

constitute a ground for divorce.

33 Nev. 44, 47 (1910) McKim v. District Court

the facts alleged in the complaint do not constitute a ground for divorce. By constructive

service he is made a party to an action in this state for the purpose of adjudicating his

matrimonial relation under laws more unfavorable to him than the laws of his domicile. If the

wife has not acquired a legal domicile in Nevada, her domicile remains by operation of law

that of her husband's and the courts of New York alone have jurisdiction of their matrimonial

relation. Surely substantial justice in such a situation will require a preliminary examination

and determination of the bona fides of her residence when it is challenged without requiring

defendant to change his status in relation to the action by filing of an answer and submitting

personally to the jurisdiction of the court. This can be done in no other way known to the law

than by plea in abatement before issue, the absence of jurisdiction not appearing of record,

but, as alleged, being concealed by the false allegations of the complaint as to residence. If in

such case the court would dismiss on motion of a stranger (Haley v. Eureka Co. Bank, 17

Nev. 127; also 112 Cal. 147) in case nonjurisdiction appeared of record, how much more

jealous it should be to preliminarily inquire into the facts if a prima facie showing be made of

an attempt to impose upon the court's conditional statutory jurisdiction?

XII. The right of the defendant to appear specially for the purpose of such plea to the

jurisdiction of the court over the subject of the action is in thorough accord with the

recognized principles of special appearances. He is not invoking the jurisdiction of the court

and therefore by the principles of estoppel debarred from thereafter denying it; he is rather

protesting against that jurisdiction, and, denying the facts alleged to foundation it, asking the

court to examine and determine the question before issue. (Brown v. Webber, 6 Cush.

564-569; Abbott v. Semph, 25 Ill. 107; Winter v. Union Pkg. Co., 93 Pac. 930; Harkness v.

Hyde, 98 U. S. 476; Walling v. Beers, 120 Mass. 548; Jones v. Jones, 2 Am. St. 447; Eberly

v. Moore, 24 How. 147; Wheelock v. Lee, 74 N. Y. 495; Higgins v. Beveridge, 55 Minn.

33 Nev. 44, 48 (1910) McKim v. District Court

Beveridge, 55 Minn. 285; Shubbock v. Cleveland, 5 Am. St. 865; Merrill v. Houghton, 51 N.

H. 61; Cleghorn v. Waterman, 16 Neb. 226; Bailey v. Schrader, 34 Black (Ind.) 260;

Sommers v. Sommers, 16 Bradwell (Ill. App.) 77; Sutherland Code P. & P., vol. 1, sec. 1101,

p. 683.)

XIII. Where special appearance is sought for purpose of attacking jurisdiction of the

subject of the action, permission of court should be first obtainednot only as a matter of

good practice, but on principle. (1 Dan. Chan. Prac., star p. 538; Wright v. Boynton, 72 Am.

Dec. 320.)

XIV. Provisions of section 3594 as to what shall constitute appearance held in California

to be exclusive; hence any other form of appearance necessary not general but special.

(Voorman v. Li Po Tai, 113 Cal. 302; Powers v. Braley, 75 Cal. 237.)

XV. Even if the authorities were not abundant justifying a special appearance for the

purpose of attacking jurisdiction of subject of action, such right would surely arise under the

liberal provisions of Comp. Laws, 506, in view of the sui generis character of the action both

as to jurisdiction and service upon nonresidents.

XVI. It should be borne in mind that a very different rule prevails where the special

appearance is for the purpose of challenging the jurisdiction of the person of the defendant

from that recognized where the challenge is directed to the jurisdiction of the subject of the

action. Also there is good reason for differentiating the special appearance of one out of the

state constructively served from that of one within the state personally served in this sui

generis class of cases where such special appearance is for the sole purpose of challenging

jurisdiction of the subject of the action.

XVII. Remains then the sole question: Did the action of the district court in this case

amount to the denial to the defendant of a right to which he is entitled as a matter of law, viz:

the right to have his challenge to the jurisdiction of the subject of the action entertained and

determined prior to joinder of issue upon the merits? If the action of the district court

amounted to that, or was tantamount to that, then he has been denied a legal right,

whatever the form of his application or the nature of the court's decision.

33 Nev. 44, 49 (1910) McKim v. District Court

was tantamount to that, then he has been denied a legal right, whatever the form of his

application or the nature of the court's decision.

It boots nothing to say that this application for a writ is premature because the petitioner

has not tendered his plea for filing and been refused; or that this court in granting the writ

would be reversing a decision of the court below.

The application below was for permission to appear specially for the purposes of the plea.

The court's decision was to the effect that the defendant could not appear specially for that or

any other purpose. The effect of the decision was to deny the defendant the right to challenge

the court's jurisdiction of the subject-matter before issue upon the merits.

The plea in abatement could not have been filed in connection with a special appearance

after that decision; and if it had been so filed, if it had not amounted to a contempt,

permission therefor having been denied, it would have been a useless thing to do when it

appears certain from the court's decision that it would have been stricken upon motion.

(Gamble v. District Court, 27 Nev. 233.)

And here, too, the latitude of the rule of Comp. Laws, 506, should prevail, if it should be

necessary to invoke it, to the end that substantial justice may be attained, in that petitioner

has made an effort in good faith and with all proper regard for the rights of both the court and

the adverse party to exercise what he claims to be a plain legal right. No technical objection

to the issuance of the writ should be regarded if the right be his in law and the action of the

court was tantamount to a denial of it.

XVIII. A writ of mandate will issue to compel the performance of an act which the law

enjoins, or to compel the admission of a party to a right to which he is entitled. (Comp. Laws,

3542.)

The writ will not run to compel an inferior tribunal how to act, but will run to compel it in

this case to entertain the challenge to jurisdiction and determine the question of the bona

fides of plaintiff's residence involved therein on the basis of a special appearance.

33 Nev. 44, 50 (1910) McKim v. District Court

tain the challenge to jurisdiction and determine the question of the bona fides of plaintiff's

residence involved therein on the basis of a special appearance. (Treadway v. Wright, 4 Nev.

119; Cavanaugh v. Wright, 2 Nev. 166; State v. Murphy, 22 Nev. 77; State v. Murphy, 19

Nev. 89-94; Floral Spring Water Co. v. Rives, 14 Nev. 431; State v. Wright, 10 Nev.

167-175; note, 98 Am. St. Rep. 890; Wright v. Mesnard, 63 N. W. 1000; Pros. Atty. v. Rec.

Court (Mich.), 26 N. W. 694: Brown v. Cir. Judge (Mich.), 42 N. W. 826.)

Boyd & Salisbury (Horatio Alling, of counsel), for Respondents.

By the Court, Norcross, C. J.:

An action for divorce was instituted by Margaret E. McKim, as plaintiff, against Smith H.

McKim, as defendant, in the Second Judicial District Court of the State of Nevada, in and for

the County of Washoe, before Honorable W. H. A. Pike, district judge. The said defendant,

petitioner herein, through his attorney, James Glynn, served notice upon the plaintiff,

Margaret E. McKim, that upon a time certain he would move the said district court for an

order permitting him to appear specially in the action for the purposes of filing a plea in

abatement, raising the question of the jurisdiction of the said district court to try the action for

divorce, upon the ground that the plaintiff, the said Margaret E. McKim, was not at the time

of the filing of her complaint, nor for six months immediately prior thereto, nor at all, a bona

fide resident of the said county of Washoe or of the State of Nevada, as alleged in her