Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Criminal Procedure Cases

Загружено:

Zaira Gem GonzalesАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Criminal Procedure Cases

Загружено:

Zaira Gem GonzalesАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

PEOPLE VS.

BATIN FACTS: Eugenios wife, Josephine Refugio testified she glanced to her left and saw Neil Batin standing at the gate to their compound, looking towards her and her husband. A few moments later, Neil went to one of the parked cars, opened its door, and took a gun from inside. She next noticed Castor going towards Neil as the latter stood at the side of the car and shouting: "Huwag!" Castor grabbed the gun from Neil. After the gun was taken from him, Neil just proceeded towards the right rear of the car. Castor followed Neil and handed the gun back to him. When she shifted her glance from the Batins, Josephine heard Castor ordering his son: "Sige, banatan mo na." Neil responded by drawing the gun from his waistline, raising and aiming it at her and her husband, and firing twice from his eye-level. Both Josephine and Eugenio fell to the ground, the former, backwards, and the latter landing on top of her. Neighbors testified that Neil went out to the street, went between the parked white car and yellow taxicab, aimed the gun at Eugenio and Josephine who were at the mango tree, and then asked Castor: "Tay, banatan ko na?"; that Castor replied: "Sige, anak, banatan mo na." ISSUE: Whether or not the statement made by the father made him liable as principal by inducement? HELD: The Court finds that Castor and Neil conspired in shooting Eugenio. This finding is inexorable because the testimonies of the Prosecution witnesses that Castor returned the gun back to Neil; that he instigated Neil to shoot by shouting: "Sige, banatan mo na"; and that Neil then fired his gun twice were credible and sufficed to prove Castors indispensable cooperation in the killing of Eugenio. Accordingly, Castor was as much liable criminally for the death of Eugenio as Neil, the direct participant in the killing, was. While Castor was indeed heard to have shouted "Huwag," this cannot be considered as reliable evidence that he tried to dissuade Neil from firing the gun. It was established by credible testimony that he handed back the gun to Neil and urged him to shoot the Refugio spouses. Josephine Refugio plainly stated on crossexamination that Castor shouted "Huwag" while inside the car grappling for possession of the gun, and not when Neil was aiming the gun at the spouses.

As concluded by the trial court, the circumstances surrounding Castors utterance of "Huwag!" shows beyond doubt that Castor shouted the same, not to stop Neil from firing the gun, but to force him to leave the use of the gun to Castor. These circumstances only confirm the conspiracy between the Batins in committing the crime: after the Batins grappled for the gun and Castor shouted "Huwag," Castor finally decided to give the gun to Neil a crystal-clear expression of the agreement of the Batins concerning the commission of a felony. Conspiracy may also be deduced from the acts of the appellants before, during, and after the commission of the crime which are indicative of a joint purpose, concerted action, and concurrence of sentiments.Even if we pursue the theory that the defense is trying to stir us to, the results would be the same. Castors argument is that "(h)is alleged utterance of the words Sige, banatan mo na cannot be considered as the moving cause of the shooting and, therefore, he cannot be considered a principal by inducement. Inducement may be by acts of command, advice or through influence or agreement for consideration. The words of advice or the influence must have actually moved the hands of the principal by direct participation. We have held that words of command of a father may induce his son to commit a crime. The moral influence of the words of the father may determine the course of conduct of a son in cases in which the same words coming from a stranger would make no impression. There is no doubt in our minds that Castors words were the determining cause of the commission of the crime. PEOPLE VS. CHING FACTS: CA affirmed with modification the RTC conviction of accused-appellant William Ching from three counts of rape committed against his minor daughter, AAA who was only 12 years old when the alleged crime was committed. CA reduced the penalty from death penalty to reclusion perpetua. The prosecution presented AAA, AAA's mother, BBB, among others as witnesses. The AAA was the third child in eight children born to appellant and BBB. Sometime in the year 1996, the appellant instructed AAA's four other siblings to play outside, while AAA was cooking inside then Ching instructed AAA to go in his bedroom and thereafter inserted his penis to the victim's vagina after removing her shorts and panty. The victim screamed for help but to no avail as the appellant also threatened the girl of killing her. AAA did not reported the

incident to anybody. For the second time and third time in 1998, Appellant had carnal knowledge with the girl when her sibling was asleep. Meantime, Ching was arrested from June 1998 to February of 2009 for drug pushing. When he was subsequently released he went to the place where AAA was employed and asked for money, AAA refused and reported not just the commotion caused by Ching but the times when she was raped. In the petition for review before the Supreme Court, the appellant asserted that CA erred in not considering the information filed against accused-appellant as to the approximate date of the commission of the alleged rapes. ISSUE: Whether the accused-appellant constitutional right to be inform of the nature and cause of the accusation against him was violated? HELD: The contention was devoid of merit. An

complainant and her children were sleeping inside their house when Domingo when she was awakened when the accused entered their kitchen armed with a screwdriver and a kitchen knife. He stabbed the complainant and her children. Raquel Indon, complainant, pleaded the appellant to spare her daughter but teh appellant answered Ngayon pa, nagawa ko na. Two of her children died. Five years passed, the defense counsel said that nine days prior the commission of the crime, appellant suffered sleeplessness, lack of appetite, and nervousness. Occasionally, a voice would tell him to kill. Appellant averred that when he regained his memory, one week had already passed since the incidents, and he was already detained. They submitted a psychiatric evaluation, and psychological examination as evidence that appellant suffered from Schizophrenia, a mental disorder characterized by the presence of delusions and or hallucinations, disorganized speech and behavior, poor impulse control and low frustration tolerance. The doctor could not find out when the appellant started to suffer this illness, but the symptoms of Schizophrenia which were manifested by the patient indicated that he suffered from the illness six months before the Center examined the appellant. The counsel of the appellant raised the defense of insanity of the appellant. ISSUE: Whether or not the appellant is exempted from criminal liability on the ground of insanity. HELD: No, the defense of insanity is unmeritorious. Insanity exempts the accused only when the finding of mental disorder refers to appellants state of mind immediately before or at the very moment of the commission of the crime. This was not the case in the issue at bar, what was presented was proof of appellants mental disorder that existed five years after the incident, but not at the time the crimes were committed. The RTC also considered it crucial that appellant had the presence of mind to respond to Raquel Indons pleas that her daughters be spared by saying, Ngayon pa, nagawa ko na. Even assuming that nine days prior the crime the appellant was hearing voices ordering him to kill people, while suggestive of an abnormal mental condition, cannot be equated with a total deprivation of will or an absence of the power to discern. Mere abnormality of mental faculties will not exclude imputability. The law presumes every man to be of sound mind. Otherwise stated, the law presumes that all acts are voluntary, and that it is improper to presume that acts are done unconsciously. Thus, a person accused of a crime

information is an accusation in writing, to be valid and sufficient, an information must state the name of the accused, the designation of the offense, the acts complained of as constituting an offense and the approximate date and time of its commission and the place. With respect to the time, It is expressed in Section 11, Rule 110 of the Revised Rules of Criminal Procedure that it is not necessary to state in the information the precise date of the offense. Especially in rape cases, where failure to specify the exact dates and times does not ipso facto make the information defective. As held in People vs. Purazo, date is not an essential element of the crime of rape, for the gravamen of the offense is carnal knowledge of a woman. As such, the time or place of commission in rape cases need not be accurately stated. The allegations in the informations which stated that the three incidents of rape were committed in the year 1996 and in May 1998 are sufficient to affirm the conviction of appellant in the instant case. The imposition of death penalty was proper, however due to RA 9346, CA was just proper in reducing the said penalty. Hence, CA decision AFFIRMED in toto. No costs. PEOPLE v. DOMINGO FACTS: The Court of Appeals found appellant Jesus Domingo guilty beyond reasonable doubt of murder, attempted murder, frustrated murder, and frustrated homicide. On or about the 29th day of March 2000,

who pleads the exempting circumstance of insanity has the burden of proving beyond reasonable doubt that he or she was insane immediately before or at the moment the crime was committed. PEOPLE VS. IBANEZ FACTS: Ibanez was charged with three counts of raping his own daughter under three pieces of information before the RTC of Cavite. When arraigned he plead not guilty. On the 1st charge, AAA testified she was at their home in Cavite and did not inform anyone of the incident (June 1997). On the 2nd charge, AAA testified being raped 8 times from January to December 1998. The 3rd rape happened sometime in April 1999 while her mother was at work. After which, she told her cousin who brought her to the NBI, where complaint affidavit was executed. Ibanez denied having raped his daughter with an alibi of being always away from home. ISSUE: Whether or not the precise dates of the commission of the rape be alleged in the information HELD: NO. An information is valid as long as it distinctly states the elements of the offense and the acts or omissions constitutive thereof. The exact date of the commission of a crime is not an essential element of the crime charged. Thus, in a prosecution for rape, the material fact or circumstance to be considered is the occurrence of the rape, not the time of its commission. The gravamen of the offense is carnal knowledge of a woman. Theprecise time of the crime has no substantial bearing on its commission. Therefore, it is not essential that it be alleged in the information with ultimate precision. The allegation in the pieces of information that the appellant committed the rape "sometime in June 1997 and "sometime in April 1999 was sufficient to inform appellant that he was being charged of qualified rape committed against his daughter. The allegation adequately afforded appellant an opportunity to prepare his defense. Thus, appellant cannot complain that he was deprived of his right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation against him. It was also too late for appellant to question the sufficiency of the criminal pieces of information since he

had himself arraigned and entered a plea of not guilty to the crime of rape which is equivalent to waiving his right to object to the pieces of information on the ground of an error as to the time of the alleged rape. HUN HYUNG PARK v EUNG WON CHOI FACTS: Eung Won Choi, was charged for violation of BP 22, otherwise known as the Bouncing Checks Law, for issuing PNB Check No. 0077133 postdated August 28, 1999 in the amount of P1,875,000 which was dishonored for having been drawn against insufficient funds. He pleaded not guilty. After the prosecution rested its case, respondent filed a Motion for Leave of Court to File Demurrer to Evidence to which he attached his Demurrer, asserting that the prosecution failed to prove that he received the notice of dishonor, hence, the presumption of the element of knowledge of insufficiency of funds did not arise. - (2/27/03) The MeTC of Makati, Branch 65 granted the demurrer and dismissed the case. The prosecutions motion for reconsideration was denied. Park appealed the civil aspect of the case to the RTC of Makati, contending that the dismissal of the criminal case should not include its civil aspect. The RTC held that while the evidence presented was insufficient to prove Chois criminal liability, it did not altogether extinguish his civil liability. It accordingly granted Parks appeal and ordered Choi to pay him P1,875,000 with legal interest. Upon Chois motion for reconsideration, however, the RTC set aside its decision and ordered the remand of the case to the MeTC for further proceedings, so that Choi may adduce evidence on the civil aspect of the case. Parks motion for reconsideration of the remand of the case having been denied, he elevated the case to the CA which dismissed his petition. ISSUES: 1. Whether or not the CA erred in dismissing the petition for not fully complying with verification requirements 2. Whether or not the CA erred in dismissing the petition on the ground that it was not accompanied by copies of certain pleadings and other material portions of the record as would support the allegations of the petition

3. Whether or not the CA erred in dismissing the petition for failure to implead the People of the Philippines as a party 4. Whether or not the respondent has a right to present evidence on the civil aspect of the case in view of his demurrer HELD: 1. NO Ratio Verification is not an empty ritual or a meaningless formality. Its import must never be sacrificed in the name of mere expedience or sheer caprice. For what is at stake is the matter of verity attested by the sanctity of an oath to secure an assurance that the allegations in the pleading have been made in good faith, or are true and correct and not merely speculative. Reasoning - Section 4 of Rule 7 of the RoC: Verification Except when otherwise specifically required by law or rule, pleadings need not be under oath, verified or accompanied by affidavit. A pleading is verified by an affidavit that the affiant has read the pleading and that the allegations therein are true and correct of his personal knowledge or based on authentic records. - A pleading required to be verified which contains a verification based on information and belief, or upon knowledge, information and belief, or lacks a proper verification shall be treated as an unsigned pleading. - Park argues that the word or is a disjunctive term signifying disassociation and independence, hence, he chose to affirm in his petition he filed before the court a quo that its contents are true and correct of my own personal knowledge, and not on the basis of authentic documents. On the other hand, Choi counters that the word or may be interpreted in a conjunctive sense and construed to mean as and, or vice versa, when the context of the law so warrants. - A pleading may be verified under either of the two given modes or under both. The veracity of the allegations in a

pleading may be affirmed based on either ones own personal knowledge or on authentic records, or both, as warranted. The use of the preposition or connotes that either source qualifies as a sufficient basis for verification and, needless to state, the concurrence of both sources is more than sufficient. Bearing both a disjunctive and conjunctive sense, this parallel legal signification avoids a construction that will exclude the combination of the alternatives or bar the efficacy of any one of the alternatives standing alone. - However, the range of permutations is not left to the pleaders liking, but is dependent on the surrounding nature of the allegations which may warrant that a verification be based either purely on personal knowledge, or entirely on authentic records, or on both sources. Authentic records as a basis for verification bear significance in petitions where the greater portions of the allegations are based on the records of the proceedings in the court of origin, and not solely on the personal knowledge of the petitioner. - To sustain petitioners explanation that the basis of verification is a matter of simple preference would trivialize the rationale and diminish the resoluteness of the rule. It would play on predilection and pay no heed in providing enough assurance of the correctness of the allegations. 2. NO Ratio Procedural rules are tools designed to facilitate the adjudication of cases. Courts and litigants alike are thus enjoined to abide strictly by the rules. And while the Court, in some instances, allows a relaxation in the application of the rules, this, we stress, was never intended to forge a bastion for erring litigants to violate the rules with impunity. The liberality in the interpretation and application of the rules applies only in proper cases and under justifiable causes and circumstances. While it is true that litigation is not a game of technicalities, it is equally true that every case must be prosecuted in accordance with the prescribed procedure to insure an orderly and speedy administration of justice. Reasoning - The materiality of those documents is very apparent since the civil aspect of the case, from which Park is

appealing, was likewise dismissed by the trial court on account of the same Demurrer. The Rules require that the petition must be accompanied by clearly legible duplicate original or true copies of the judgments or final orders of both lower courts, certified correct by the clerk of court [Sec 2(d) Rule 42]. - The only duplicate original or certified true copies attached as annexes to the petition are the RTC Order granting respondents MFR and the RTC Order denying petitioners MFR. The copy of the September 11, 2003 RTC Decision, which petitioner prayed to be reinstated, is not a certified true copy and is not even legible. Petitioner later recompensed though by appending to his MFR a duplicate original copy. - While petitioner averred before the CA in his MFR that the February 27, 2003 MeTC Order was already attached to his petition as Annex G, Annex G bares a replicate copy of a different order. It was to this Court that petitioner belatedly submitted an uncertified true copy of the said MeTC Order as an annex to his Reply to respondents Comment. The copy of the other MeTC Order, dated May 5, 2003, which petitioner attached to his petition before the CA is similarly uncertified as true. Since both Orders were adverse to him even with respect to the civil aspect of the case, petitioner was mandated to submit them in the required form. 3. YES Reasoning - The MeTC acquitted respondent. As a rule, a judgment of acquittal is immediately final and executory and the prosecution cannot appeal the acquittal because of the constitutional prohibition against double jeopardy. Either the offended party or the accused may, however appeal the civil aspect of the judgment despite the acquittal of the accused. The public prosecutor has generally no interest in appealing the civil aspect of a decision acquitting the accused. The acquittal ends his work. The case is terminated as far as he is concerned. The real parties in interest in the civil aspect of a decision are the offended party and the accused. 4. YES Reasoning

- In case of a demurrer to evidence filed with leave of court, the accused may adduce countervailing evidence if the court denies the demurrer. Such denial bears no distinction as to the two aspects of the case because there is a disparity of evidentiary value between the quanta of evidence in such aspects of the case. In other words, a court may not deny the demurrer as to the criminal aspect and at the same time grant the demurrer as to the civil aspect, for if the evidence so far presented is not insufficient to prove the crime beyond reasonable doubt, then the same evidence is likewise not insufficient to establish civil liability by mere preponderance of evidence. - On the other hand, if the evidence so far presented is insufficient as proof beyond reasonable doubt, it does not follow that the same evidence is insufficient to establish a preponderance of evidence. For if the court grants the demurrer, proceedings on the civil aspect of the case generally proceed. The only recognized instance when an acquittal on demurrer carries with it the dismissal of the civil aspect is when there is a finding that the act or omission from which the civil liability may arise did not exist. Absent such determination, trial as to the civil aspect of the case must perforce continue. - In the instant case, the MeTC granted the demurrer and dismissed the case without any finding that the act or omission from which the civil liability may arise did not exist. Choi did not assail the RTC order of remand. He thereby recognized that there is basis for a remand. - Park posits that Choi waived his right to present evidence on the civil aspect of the case (1) when the grant of the demurrer was reversed on appeal, citing Section 1 of Rule 33, and (2) when respondent orally opposed petitioners motion for reconsideration pleading that proceedings with respect to the civil aspect of the case continue. - Petitioners citation of Section 1 of Rule 33 is incorrect. Where a court has jurisdiction over the subject matter and over the person of the accused, and the crime was committed within its territorial jurisdiction, the court necessarily exercises jurisdiction over all issues that the law requires it to resolve. One of the issues in a criminal case being the civil liability of the accused arising from the crime, the governing law is the Rules of Criminal Procedure, not the Rules of Civil Procedure which pertains

to a civil action arising from the initiatory pleading that gives rise to the suit. - As for petitioners attribution of waiver to respondent, it cannot be determined with certainty from the records the nature of Chois alleged oral objections to Parks motion for reconsideration of the grant of the demurrer to evidence. Any waiver of the right to present evidence must be positively demonstrated. Any ambiguity in the voluntariness of the waiver is frowned upon; hence, courts must indulge every reasonable presumption against it. Dispositive Petition is DENIED. DOMAGSANG VS. CA FACTS: Josephine Domagsang obtained a loan from Ignacio Garcia in the amount of P573,800.00. In consideration of the loan, Domagsang issued eighteen (18) postdated checks to Ignacio. When presented for payment, the said checks bounced for the reasons "Account Closed". Ignacio demanded payment by calling up Domagsang at her office. However, Domagsang failed to pay. Both the RTC and Court of Appeals convicted Domagsang of the crime. The latter appealed to the Supreme Court. ISSUE: Whether or not a verbal notice of dishonor or demand to pay enough to convict a person for violation of Batas Pambansa Blg. 22 (Bouncing Checks Law). HELD: The Supreme Court held that Although Section 2 of B.P. Blg. 22 does state that the notice of dishonor be in writing, Section 3 states that where there are no sufficient funds in or credit with the drawee bank, such fact shall always be explicitly stated in the notice of dishonor or refusal. A mere oral notice or demand to pay would appear to be insufficient for conviction under the law. Both the spirit and letter of the Bouncing Checks Law require for the act to be punished thereunder not only that the accused issued a check that is dishonored, but that likewise the accused has actually been notified in writing of the fact of dishonor. The consistent rule is that penal statutes have to be construed strictly against the State and liberally in favor of the accused. Domagsang was acquitted of the crime. However, she was ordered to pay Ignacio the total face value of the dishonored checks as it was established that she failed to pay her debt.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Wills Paras Book Summary PDFДокумент61 страницаWills Paras Book Summary PDFMark Abragan88% (8)

- Wills Paras Book Summary PDFДокумент61 страницаWills Paras Book Summary PDFMark Abragan88% (8)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Answers Chapter 4 QuizДокумент2 страницыAnswers Chapter 4 QuizZenni T XinОценок пока нет

- F8 Theory NotesДокумент29 страницF8 Theory NotesKhizer KhalidОценок пока нет

- Retainer AgreementДокумент5 страницRetainer AgreementZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- CRIM LAW 1 Midterm ExamДокумент16 страницCRIM LAW 1 Midterm ExamMichyLG100% (4)

- CRIM LAW 1 Midterm ExamДокумент16 страницCRIM LAW 1 Midterm ExamMichyLG100% (4)

- NOTES - Criminal CasesДокумент3 страницыNOTES - Criminal CasesZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Appeal LetterДокумент1 страницаAppeal LetterZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- PERJURY (Ombudsman's Case)Документ2 страницыPERJURY (Ombudsman's Case)Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- PERJURY (Ombudsman's Case)Документ2 страницыPERJURY (Ombudsman's Case)Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

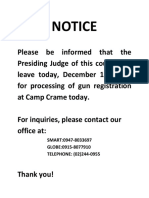

- NOTICE - On LeaveДокумент1 страницаNOTICE - On LeaveZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Justice Magdangal de Leon Outline Updates in Civ Pro and Spec ProДокумент23 страницыJustice Magdangal de Leon Outline Updates in Civ Pro and Spec ProArElleBeeОценок пока нет

- Political Law Review - Midterm Exam CoverageДокумент3 страницыPolitical Law Review - Midterm Exam CoverageZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. ZZZ - J.LEONENДокумент14 страницPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. ZZZ - J.LEONENZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- TaxationДокумент14 страницTaxationZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Nationality & CitizenshipДокумент12 страницNationality & CitizenshipZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Eversley vs. Spouses Anastacio - G.R. No. 195814, April 4, 2018Документ18 страницEversley vs. Spouses Anastacio - G.R. No. 195814, April 4, 2018Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Lectures of Atty. Japar B. Dimampao: Tax Notes (Legal Ground)Документ106 страницLectures of Atty. Japar B. Dimampao: Tax Notes (Legal Ground)Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Civil Procedure 1Документ119 страницCivil Procedure 1Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Criminal Law-Bar ExaminationsДокумент136 страницCriminal Law-Bar ExaminationsZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- What Is International Humanitarian Law (IHL)Документ14 страницWhat Is International Humanitarian Law (IHL)Joseph PamaongОценок пока нет

- Justice Magdangal de Leon Outline Updates in Civ Pro and Spec ProДокумент23 страницыJustice Magdangal de Leon Outline Updates in Civ Pro and Spec ProArElleBeeОценок пока нет

- POLITCAL LAW (Legislative & Executive Department) - Zaira Gee's Notes 3Документ20 страницPOLITCAL LAW (Legislative & Executive Department) - Zaira Gee's Notes 3Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- POLITCAL LAW (Right To Bail-Citizenship) - Zaira Gee's Notes 2Документ17 страницPOLITCAL LAW (Right To Bail-Citizenship) - Zaira Gee's Notes 2Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- POLITCAL LAW - 1987 Constitution & Bill of Rights - Zaira Gee's Notes 1Документ46 страницPOLITCAL LAW - 1987 Constitution & Bill of Rights - Zaira Gee's Notes 1Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- What Is International Humanitarian Law (IHL)Документ14 страницWhat Is International Humanitarian Law (IHL)Joseph PamaongОценок пока нет

- EvidenceДокумент87 страницEvidenceZaira Gem Gonzales100% (1)

- Azucena SummaryДокумент55 страницAzucena SummaryZaira Gem Gonzales100% (1)

- Criminal Law Review Bullets by Atty Leonor BoadoДокумент9 страницCriminal Law Review Bullets by Atty Leonor BoadoGarilaoОценок пока нет

- Special Proceedings - RianoДокумент31 страницаSpecial Proceedings - RianoZaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- De Lima v. Gatdula G.R. No. 204528, February 19, 2013Документ1 страницаDe Lima v. Gatdula G.R. No. 204528, February 19, 2013Zaira Gem GonzalesОценок пока нет

- Tenancy Contract 1.4 PDFДокумент2 страницыTenancy Contract 1.4 PDFAnonymous qKLFm7e5wgОценок пока нет

- Cases NOvember 21Документ31 страницаCases NOvember 21Wilfredo Guerrero IIIОценок пока нет

- First Church of Seventh-Day Adventists Weekly Bulletin (Spring 2013)Документ12 страницFirst Church of Seventh-Day Adventists Weekly Bulletin (Spring 2013)First Church of Seventh-day AdventistsОценок пока нет

- Presentation Flow: Public © 2023 SAP SE or An SAP Affiliate Company. All Rights Reserved. ǀДокумент31 страницаPresentation Flow: Public © 2023 SAP SE or An SAP Affiliate Company. All Rights Reserved. ǀAbhijeet PawarОценок пока нет

- Parole and ProbationДокумент12 страницParole and ProbationHare Krishna RevolutionОценок пока нет

- Kajian 24 KitabДокумент2 страницыKajian 24 KitabSyauqi .tsabitaОценок пока нет

- 1394308827-Impressora de Etiquetas LB-1000 Manual 03 Manual Software BartenderДокумент55 страниц1394308827-Impressora de Etiquetas LB-1000 Manual 03 Manual Software BartenderMILTON LOPESОценок пока нет

- Homework For Non Current Assets Held For SaleДокумент2 страницыHomework For Non Current Assets Held For Salesebosiso mokuliОценок пока нет

- Squatting Problem and Its Social Ills in MANILAДокумент10 страницSquatting Problem and Its Social Ills in MANILARonstar Molina TanateОценок пока нет

- TNPSC Group 1,2,4,8 VAO Preparation 1Документ5 страницTNPSC Group 1,2,4,8 VAO Preparation 1SakthiОценок пока нет

- CFS Session 1 Choosing The Firm Financial StructureДокумент41 страницаCFS Session 1 Choosing The Firm Financial Structureaudrey gadayОценок пока нет

- BS-300 Service Manual (v1.3)Документ115 страницBS-300 Service Manual (v1.3)Phan QuanОценок пока нет

- Labour and Industrial Law: Multiple Choice QuestionsДокумент130 страницLabour and Industrial Law: Multiple Choice QuestionsShubham SaneОценок пока нет

- A Choral FanfareДокумент5 страницA Choral FanfareAdão RodriguesОценок пока нет

- 2000 CensusДокумент53 страницы2000 CensusCarlos SmithОценок пока нет

- PAS 7 and PAS 41 SummaryДокумент5 страницPAS 7 and PAS 41 SummaryCharles BarcelaОценок пока нет

- Ivory L. Haislip v. Attorney General, State of Kansas and Raymond Roberts, 992 F.2d 1085, 10th Cir. (1993)Документ5 страницIvory L. Haislip v. Attorney General, State of Kansas and Raymond Roberts, 992 F.2d 1085, 10th Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Financial Analysts - Occupational Outlook Handbook - U.S. Bureau of Labor StatisticsДокумент6 страницFinancial Analysts - Occupational Outlook Handbook - U.S. Bureau of Labor StatisticsHannah Denise BatallangОценок пока нет

- The Tipster1901, From "Wall Street Stories" by Lefevre, EdwinДокумент20 страницThe Tipster1901, From "Wall Street Stories" by Lefevre, EdwinGutenberg.orgОценок пока нет

- 9 Keland Cossia 2019 Form 1099-MISCДокумент1 страница9 Keland Cossia 2019 Form 1099-MISCpeter parkinsonОценок пока нет

- Bill Ackman Questions For HerbalifeДокумент40 страницBill Ackman Questions For HerbalifedestmarsОценок пока нет

- Intro To Lockpicking and Key Bumping WWДокумент72 страницыIntro To Lockpicking and Key Bumping WWapi-3777781100% (8)

- July 29.2011 - Inclusion of Road Safety Education in School Curriculums SoughtДокумент1 страницаJuly 29.2011 - Inclusion of Road Safety Education in School Curriculums Soughtpribhor2Оценок пока нет

- 1st Indorsement RYAN SIMBULAN DAYRITДокумент8 страниц1st Indorsement RYAN SIMBULAN DAYRITAnna Camille TadeoОценок пока нет

- 2017 IPCC Fall-Winter Newsletter IssueДокумент10 страниц2017 IPCC Fall-Winter Newsletter IssueaprotonОценок пока нет

- Important SAP MM Tcodes 1Документ2 страницыImportant SAP MM Tcodes 1shekharОценок пока нет

- Ikyase & Olisah (2014)Документ8 страницIkyase & Olisah (2014)Dina FitrianiОценок пока нет