Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Frank Bunker Gilbreth

Загружено:

Sharmaine Grace FlorigОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Frank Bunker Gilbreth

Загружено:

Sharmaine Grace FlorigАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Frank Bunker Gilbreth (July 7, 1868, Fairfield, Maine June 14, 1924, Montclair, New Jersey) was an early

y advocate of scientific management and a pioneer of motion study, and is perhaps best known as the father and central figure of Cheaper by the Dozen. Gilbreth had no formal education beyond high school. He began as a bricklayer, became a building contractor, an inventor, and evolved into management engineer. He eventually became an occasional lecturer at Purdue University, which houses his papers. He married Lillian Moller Gilbreth in 1904; they had 12 children, 11 of whom survived him. Gilbreth died suddenly of heart failure at age 55. Lillian outlived him by 48 years. Gilbreth discovered his vocation when, as a young building contractor, he sought ways to make bricklaying (his first trade) faster and easier. This grew into a collaboration with his eventual spouse, Lillian Moller Gilbreth, that studied the work habits of manufacturing and clerical employees in all sorts of industries to find ways to increase output and make their jobs easier. He and Lillian founded a management consulting firm, Gilbreth, Inc., focusing on such endeavors. According to Claude George (1968), Gilbreth reduced all motions of the hand into some combination of 18 basic motions. These included grasp, transport loaded, and hold. Gilbreth named the motions therbligs, "Gilbreth" spelled backwards with the transposed. He used a motion picture camera that was calibrated in fractions of minutes to time the smallest of motions in workers. George noted that the Gilbreths were, above all, scientists who sought to teach managers that all aspects of the workplace should be constantly questioned, and improvements constantly adopted. Their emphasis on the "one best way" and the therbligs predates the development of Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) (George 1968: 98), and the late 20th century understanding that repeated motions can lead to workers experiencing repetitive motion injuries. Gilbreth was the first to propose that a surgical nurse serve as "caddy" (Gilbreth's term) to a surgeon, by handing surgical instruments to the surgeon as called for. Gilbreth also devised the standard techniques used by armies around the world to teach recruits how to rapidly disassemble and reassemble their weapons even when blindfolded or in total darkness. These innovations have arguably helped save millions of lives. Although the Gilbreths' work is often associated with that of Frederick Winslow Taylor, there was a substantial philosophical difference between the Gilbreths and Taylor. The symbol of Taylorism was the stopwatch, and Taylorism was primarily concerned with reducing the time of processes. The Gilbreths sought to make processes more efficient by reducing the motions involved. They saw their approach as more concerned with workers' welfare than was Taylorism, which workers often perceived as primarily concerned with profit. This led to a personal rift between Taylor

and the Gilbreths, which after Taylor's death turned into a feud between the Gilbreths and Taylor's followers. After Frank's death, Lillian Gilbreth took steps to heal the rift (Price 1990), although some friction remains over questions of history and intellectual property. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth often used their large family (and Frank himself) as guinea pigs in experiments. Their family exploits are lovingly detailed in the 1948 book Cheaper by the Dozen, written by his son Frank Jr. and daughter Ernestine Gilbreth Carey. The book inspired two films of the same name, one (1950) starring Clifton Webb and Myrna Loy, and the other (2003) starring comedians Steve Martin and Bonnie Hunt. The latter film bears no resemblance to the book except that both feature a family with twelve children. A 1950 sequel, titled Belles on Their Toes, chronicles the adventures of the Gilbreth family after Frank's 1924 death. A second sequel, Time Out For Happiness, was authored by Frank Jr. alone and published in 1971. It is out of print and considered rare.

Lillian Moller Gilbreth, BA, MA, PhD, (b. Lillian Evelyn Moller May 24, 1878, Oakland, California d. January 2, 1972, Phoenix, Arizona) was one of the first working female engineers holding a PhD. She is arguably the first true industrial/organizational psychologist. She and her husband Frank Bunker Gilbreth were pioneers in the field of industrial engineering. Their interest in time and motion study may have had something to do with the fact that they had an extremely large family. The books Cheaper By The Dozen and Belles on Their Toes are the story of their family life with their twelve children. In 1984, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp in her honor. She is considered "The First Lady of Engineering" and was the first woman elected into the National Academy of Engineering. She was a professor at Purdue University, The Newark College of Engineering and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She served as an advisor to Presidents Hoover, Roosevelt, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson on matters of civil defense, war production and rehabilitation of the physically handicapped. She and husband Frank have a permanent exhibit in The Smithsonian National Museum of American History and her portrait hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. She graduated from the University of California, Berkeley with a BA (1900) and MA (1902). Lillian completed her dissertation to obtain her Ph.D from the University of California but did not receive the degree because she was not able to complete the residency requirements. Her dissertation was called "The Psychology of Management". She later went on to earn a Ph.D from Brown University in 1915. It was the first granted in industrial psychology. She also received 22 honorary degrees from schools such as Princeton University, Brown University and the University of Michigan.

Together she and her husband were partners in the management consulting firm of Gilbreth, Inc. which performed time and motion studies. Their children took great part in this. They would do experiments together. One of the great husband-and-wife teams of science and engineering, Frank and Lillian Gilbreth early in the 1900s collaborated on the development of motion study as an engineering and management technique. Frank Gilbreth was much concerned until his death in 1924, with the relationship between human beings and human effort. Frank Gilbreth's well-known work in improving brick-laying in the construction trade is a good example of his approach. From his start in the building industry, he observed that workers developed their own peculiar ways of working and that no two used the same method. In studying bricklayers, he noted that individuals did not always use the same motions in the course of their work. These observations led him to seek one best way to perform tasks. He developed many improvements in brick-laying. A scaffold he invented permitted quick adjustment of the working platform so that the worker would be at the most convenient level at all times. He equipped the scaffold with a shelf for the bricks and mortar, saving the effort formerly required by the workman to bend down and pick up each brick. He had the bricks stacked on wooden frames, by low-priced laborers, with the best side and end of each brick always in the same position, so that the bricklayer no longer had to turn the brick around and over to look for the best side to face outward. The bricks and mortar were so placed on the scaffold that the brick-layer could pick up a brick with one hand and mortar with the other. As a result of these and other improvements, he reduced the number of motions made in laying a brick from 18 to 4 1/2. Frank and Lillian Gilbreth continued their motion study and analysis in other fields and pioneered in the use of motion pictures for studying work and workers. They orginated micro-motion study, a breakdown of work into fundamental elements now called therbligs (derived from Gilbreth spelled backwards). These elements were studied by means of a motion-picture camera and a timing device which indicated the time intervals on the film as it was exposed. After Frank Gilbreth's death, Dr. Lillian Gilbreth continued the work and extended it into the home in an effort to find the "one best way" to perform household tasks. She has also worked in the area of assistance to the handicaped, as, for instance, her design of an ideal kitchen layout for the person afflicted with heart disease. She is widely recognized as one of the world's great industrial and management engineers and has traveled and worked in many countries of the world. Frank Gilbreth ws born on July 7, 1868his centennial should mark a milestone in management and work simplification. By 1912, he left the construction business to devote himself entirely to "scientific management"a term coined, in Gantt's apartment, by a group including Gilbreth. But to him it was more than merely the mouthing of

slogans to be foisted on a worker at a job in a plant. It was a philosophy that pervaded home and school, hospital and community, in fact, life itself. It was something that could be achieved only by cooperationcooperation between engineers, educators, physiologists, psychologists, psychiatrists, economists, sociologists, statisticians, managers. Most importantat the core of it all, there was the individual, his comfort, his happiness, his service, and his dignity. By now, too, there was no mistaking the partnership even though the wife's modesty, reticence, and sex could mislead all but the knowing. However, one accomplishment is strangely the contribution of Frank Gilbreth aloneeven though she may have given of herself to make it possible. This construction is perhaps the greatest of all: the development of Lillian Moller Gilbreth. Few marriages thoughout history can match this romance of husband and wife, both whose names have become famous in the same field. The heights that such a partnership can achieve is probably best realized by attempting to name other such combinationsPierre and Marie Curie, Charles and Mary Beard, Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Elizabeth and Robert Browning. Surely there are not manybut they are impressive. Throughout his life, Lillian Gilbreth remained, in her eyes, the junior partner. After his death, she said: "I have had more in twenty years than any other woman I have known has had in a lifetime." With him gone, she knew precisely what she had to do: carry on as he would do. This meant family and work. These were tasks for which many of the Gilbreth friends offered their help. Yet these were tasks that she knew she must perform alone. How well she accomplished themmost would say is a tribute to her, her spirit, her character, her intelligence, her strength. All this she would simply and emphatically deny. For to her, it goes without saying, it was simply a tribute to Frank Gilbreth. And who is to say that she may not be right? "When it comes to the questioning method, of course he shared with all the scientific management group the belief in the value of questions and the need to ask these questions over and over determining how the thing was to be done and why it was done and how the betterment could be brought about." "The things which concerned him more than anything else were the what and the whythe what because he felt it was necessary to know absolutely what you were questioning and what you were doing or what concerned you, and then the why, the depth type of thinking which showed you the reason for doing the thing and would perhaps indicate clearly whether you should maintain what was being done or should change what was being done." "This emphasis is a little different from what most people think about Frank and his work, and about the people who worked along these ways. Generally people expect that the most emphasis would be on the where and the when and the how. The how is, of course, in most people's minds very closely identified with motion study, work study,

directed energy, work simplification or whatever name is given to this type of work today." "When he considered the what he thought continuously, not only of the ideal thing that was to be done and the ideal method that was to be used in order to get this done. That of course, was at the base of his favorite concept which was 'the quest of the one best way.' " It is both easy and difficult to analyze this First Lady of Engineering. She is the epitome of crystal-clear logiceven though she seems to be a mass of contradictions. Trained in literature, she has found her place in engineering. As an engineer, she has found people more important than machines; waging a never-ending war on fatigue. One, watching her unceasing rounds of work, activity, and travel, can rightfully believe that she has created a non-existent foe. An extremely busy woman, she seems to have more time for things than most people. And, as kind and as gentle as she is, she can don armor and do more than hold her ground in defending the right.

Вам также может понравиться

- Frederick Taylor: Submitted By: Mark Adriell C. LovendinoДокумент7 страницFrederick Taylor: Submitted By: Mark Adriell C. LovendinoMikkoMagtibayОценок пока нет

- Frank and Lillian Gilbreth ContributionДокумент3 страницыFrank and Lillian Gilbreth Contributionmrizwan11Оценок пока нет

- Lillian Moller GilbrethДокумент7 страницLillian Moller GilbrethjonОценок пока нет

- Gilbreth LOMДокумент80 страницGilbreth LOMqwerty_901Оценок пока нет

- Frank and Lillian GilbrethДокумент4 страницыFrank and Lillian GilbrethFarzana Akter 28Оценок пока нет

- Frank and Lillian Gilbreth Were A HusbandДокумент3 страницыFrank and Lillian Gilbreth Were A HusbandadibОценок пока нет

- GilbrethsДокумент4 страницыGilbrethsFaris MohammedОценок пока нет

- Importance of Productivity: Method IsДокумент3 страницыImportance of Productivity: Method IsReymar HayОценок пока нет

- Elinor Ostrom's Rules for Radicals: Cooperative Alternatives beyond Markets and StatesОт EverandElinor Ostrom's Rules for Radicals: Cooperative Alternatives beyond Markets and StatesОценок пока нет

- The Gilbreth NetworkДокумент5 страницThe Gilbreth NetworkjonОценок пока нет

- Scientific ManagementДокумент2 страницыScientific ManagementjasjeniОценок пока нет

- Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology RevolutionОт EverandOur Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology RevolutionРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (2)

- Benjamin Franklin Research Paper OutlineДокумент4 страницыBenjamin Franklin Research Paper Outlinegz9avm26100% (1)

- Jewett) University of Pennsylvania)Документ1 страницаJewett) University of Pennsylvania)Denise RepublikaОценок пока нет

- Shaping British Foreign and Defence Policy in the Twentieth Century: A Tough Ask in Turbulent TimesОт EverandShaping British Foreign and Defence Policy in the Twentieth Century: A Tough Ask in Turbulent TimesM. MurfettОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 66.163.28.139 On Wed, 17 May 2023 20:12:37 +00:00Документ14 страницThis Content Downloaded From 66.163.28.139 On Wed, 17 May 2023 20:12:37 +00:00Crisanto Jr. RegadioОценок пока нет

- Herbert Gutman. Work, Culture and Society in Industrializing America, 1815-1919Документ59 страницHerbert Gutman. Work, Culture and Society in Industrializing America, 1815-1919Alek BОценок пока нет

- Frank and Lillian GilbrethДокумент2 страницыFrank and Lillian Gilbrethralph andrew marcalinasОценок пока нет

- Benjamin Franklin - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsОт EverandBenjamin Franklin - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsОценок пока нет

- Anticipatory Delllocracy' - Britain's Tavistock Institute Brainwashed Newt by Jeffrey Steinberg - EIR-7Документ7 страницAnticipatory Delllocracy' - Britain's Tavistock Institute Brainwashed Newt by Jeffrey Steinberg - EIR-7jamixa3566Оценок пока нет

- Hitler's Gift: The True Story of the Scientists Expelled by the Nazi RegimeОт EverandHitler's Gift: The True Story of the Scientists Expelled by the Nazi RegimeРейтинг: 2.5 из 5 звезд2.5/5 (3)

- Moral Exam Part 2Документ11 страницMoral Exam Part 2Nicolò GrassoОценок пока нет

- On Fact and Fraud: Cautionary Tales from the Front Lines of ScienceОт EverandOn Fact and Fraud: Cautionary Tales from the Front Lines of ScienceРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (7)

- Herbert Butterfield: History, Providence, and Skeptical PoliticsОт EverandHerbert Butterfield: History, Providence, and Skeptical PoliticsОценок пока нет

- Ftizgerald Geography of A Revolution PDFДокумент10 страницFtizgerald Geography of A Revolution PDFsebastian_1110Оценок пока нет

- Buckminster FullerДокумент1 страницаBuckminster Fullerabdel2121Оценок пока нет

- Quiz Reading Exercise Part 2Документ1 страницаQuiz Reading Exercise Part 2Darul Rohman Ayah AmmarОценок пока нет

- The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of Its Traditional DefenseОт EverandThe Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of Its Traditional DefenseРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- Conspiracy Fact: MKULTRA and Mind Control in the United States: Conspiracy Facts Declassified, #2От EverandConspiracy Fact: MKULTRA and Mind Control in the United States: Conspiracy Facts Declassified, #2Рейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Northern Ireland’s ’68: Civil Rights, Global Revolt and the Origins of the Troubles ~ New EditionОт EverandNorthern Ireland’s ’68: Civil Rights, Global Revolt and the Origins of the Troubles ~ New EditionОценок пока нет

- BIOДокумент37 страницBIONora AguilaОценок пока нет

- 8 Things You Didn't Know About Alan Turing: Benedict CumberbatchДокумент8 страниц8 Things You Didn't Know About Alan Turing: Benedict Cumberbatchanakui14Оценок пока нет

- Benedict Cumberbatch: Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesДокумент8 страницBenedict Cumberbatch: Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesfatinshahirahОценок пока нет

- R.buckminister Fuller and The Utopian EcologyДокумент59 страницR.buckminister Fuller and The Utopian Ecologyhelios1949100% (3)

- No 22 Nikolaas Tinbergen (II) PDFДокумент7 страницNo 22 Nikolaas Tinbergen (II) PDFatsteОценок пока нет

- The Radical Campaigns of John Baxter Langley: A Keen and Courageous ReformerОт EverandThe Radical Campaigns of John Baxter Langley: A Keen and Courageous ReformerОценок пока нет

- The Chemical Age: How Chemists Fought Famine and Disease, Killed Millions, and Changed Our Relationship with the EarthОт EverandThe Chemical Age: How Chemists Fought Famine and Disease, Killed Millions, and Changed Our Relationship with the EarthРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- Darwin and Lincoln On Race and Society - 13 November 2009Документ8 страницDarwin and Lincoln On Race and Society - 13 November 2009The Royal Society of EdinburghОценок пока нет

- Environment Essay For KidsДокумент4 страницыEnvironment Essay For Kidspflhujbaf100% (2)

- The Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on TheoryОт EverandThe Invention of International Relations Theory: Realism, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the 1954 Conference on TheoryОценок пока нет

- Gerontology Research Study Paper PT 1 2Документ55 страницGerontology Research Study Paper PT 1 2api-727701816Оценок пока нет

- Bigbang ProfileДокумент5 страницBigbang ProfileSharmaine Grace Florig100% (1)

- Nursing Priorities (PTSD)Документ4 страницыNursing Priorities (PTSD)Sharmaine Grace Florig100% (1)

- Bone MetastasisДокумент11 страницBone MetastasisSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Dissiociative DisorderДокумент12 страницDissiociative DisorderSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Medical DiagnosesДокумент5 страницMedical DiagnosesSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- ResumeДокумент2 страницыResumeSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- SchizophreniaДокумент4 страницыSchizophreniaSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- 3 Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Interventions ForДокумент2 страницы3 Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Interventions ForSharmaine Grace Florig67% (3)

- Traction2012 PDFДокумент24 страницыTraction2012 PDFSharmaine Grace Florig100% (1)

- Cancers of The Gastrointestinal SystemДокумент4 страницыCancers of The Gastrointestinal SystemSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- 3 Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Interventions ForДокумент2 страницы3 Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Interventions ForSharmaine Grace Florig67% (3)

- RESEARCHДокумент2 страницыRESEARCHSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Learn KoreanДокумент12 страницLearn KoreanSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Parts of Speech TableДокумент31 страницаParts of Speech TableSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Bureaucratic Theory by Max WeberДокумент3 страницыBureaucratic Theory by Max WeberSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Bible VersesДокумент2 страницыBible VersesSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Neo - Classical TheoryДокумент3 страницыNeo - Classical TheorySharmaine Grace Florig100% (1)

- Henri FayolДокумент2 страницыHenri FayolSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Elton MayoДокумент2 страницыElton MayoSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Hyperemesis GravidarumДокумент16 страницHyperemesis GravidarumKristine Alejandro80% (5)

- Scientific Management: (Contribution of F.W. Taylor)Документ2 страницыScientific Management: (Contribution of F.W. Taylor)Sharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Lyndall UrwickДокумент1 страницаLyndall UrwickSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Max WeberДокумент2 страницыMax WeberSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Mary Parker FollettДокумент1 страницаMary Parker FollettSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Office of The Sangguniang KabataanДокумент1 страницаOffice of The Sangguniang KabataanSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Charismatic LeadershipДокумент13 страницCharismatic Leadershipsarika4990100% (1)

- Nursing Care Plan Fluid Volume DeficitДокумент2 страницыNursing Care Plan Fluid Volume DeficitSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- Nursing DiagnosisДокумент2 страницыNursing DiagnosisEMily CalvEzОценок пока нет

- One Piece Death Note Vampire Knight BleachДокумент1 страницаOne Piece Death Note Vampire Knight BleachSharmaine Grace FlorigОценок пока нет

- 1188 2665 1 SMДокумент12 страниц1188 2665 1 SMRita BangunОценок пока нет

- .IAF-GD5-2006 Guide 65 Issue 3Документ30 страниц.IAF-GD5-2006 Guide 65 Issue 3bg_phoenixОценок пока нет

- 2.a.1.f v2 Active Matrix (AM) DTMC (Display Technology Milestone Chart)Документ1 страница2.a.1.f v2 Active Matrix (AM) DTMC (Display Technology Milestone Chart)matwan29Оценок пока нет

- Analisis Kebutuhan Bahan Ajar Berbasis EДокумент9 страницAnalisis Kebutuhan Bahan Ajar Berbasis ENur Hanisah AiniОценок пока нет

- School Based Management Contextualized Self Assessment and Validation Tool Region 3Документ29 страницSchool Based Management Contextualized Self Assessment and Validation Tool Region 3Felisa AndamonОценок пока нет

- Consecration of TalismansДокумент5 страницConsecration of Talismansdancinggoat23100% (1)

- BДокумент28 страницBLubaОценок пока нет

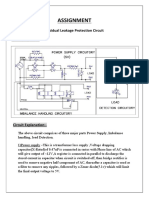

- Assignment: Residual Leakage Protection Circuit Circuit DiagramДокумент2 страницыAssignment: Residual Leakage Protection Circuit Circuit DiagramShivam ShrivastavaОценок пока нет

- Waste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFДокумент11 страницWaste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFdatinov100% (1)

- Work Energy Power SlidesДокумент36 страницWork Energy Power Slidessweehian844100% (1)

- VOTOL EMController Manual V2.0Документ18 страницVOTOL EMController Manual V2.0Nandi F. ReyhanОценок пока нет

- Project Name: Repair of Afam Vi Boiler (HRSG) Evaporator TubesДокумент12 страницProject Name: Repair of Afam Vi Boiler (HRSG) Evaporator TubesLeann WeaverОценок пока нет

- Modern Construction HandbookДокумент498 страницModern Construction HandbookRui Sousa100% (3)

- Pitch DeckДокумент21 страницаPitch DeckIAОценок пока нет

- MSDS Buffer Solution PH 4.0Документ5 страницMSDS Buffer Solution PH 4.0Ardhy LazuardyОценок пока нет

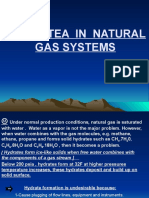

- Chapter 2 HydrateДокумент38 страницChapter 2 HydrateTaha Azab MouridОценок пока нет

- CSWIP-WP-19-08 Review of Welding Procedures 2nd Edition February 2017Документ6 страницCSWIP-WP-19-08 Review of Welding Procedures 2nd Edition February 2017oberai100% (1)

- Multiple Choice Practice Questions For Online/Omr AITT-2020 Instrument MechanicДокумент58 страницMultiple Choice Practice Questions For Online/Omr AITT-2020 Instrument Mechanicمصطفى شاكر محمودОценок пока нет

- Hyundai SL760Документ203 страницыHyundai SL760Anonymous yjK3peI7100% (3)

- Course Outline ENTR401 - Second Sem 2022 - 2023Документ6 страницCourse Outline ENTR401 - Second Sem 2022 - 2023mahdi khunaiziОценок пока нет

- Construction Project - Life Cycle PhasesДокумент4 страницыConstruction Project - Life Cycle Phasesaymanmomani2111Оценок пока нет

- Sim Uge1Документ62 страницыSim Uge1ALLIAH NICHOLE SEPADAОценок пока нет

- TIA Guidelines SingaporeДокумент24 страницыTIA Guidelines SingaporeTahmidSaanidОценок пока нет

- Supply List & Resource Sheet: Granulation Techniques DemystifiedДокумент6 страницSupply List & Resource Sheet: Granulation Techniques DemystifiedknhartОценок пока нет

- I. Choose The Best Option (From A, B, C or D) To Complete Each Sentence: (3.0pts)Документ5 страницI. Choose The Best Option (From A, B, C or D) To Complete Each Sentence: (3.0pts)thmeiz.17sОценок пока нет

- Pearson R CorrelationДокумент2 страницыPearson R CorrelationAira VillarinОценок пока нет

- Source:: APJMR-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Business-Establishments - PDF (Lpubatangas - Edu.ph)Документ2 страницыSource:: APJMR-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Business-Establishments - PDF (Lpubatangas - Edu.ph)Ian EncarnacionОценок пока нет

- Title: Smart Monitoring & Control of Electrical Distribution System Using IOTДокумент27 страницTitle: Smart Monitoring & Control of Electrical Distribution System Using IOTwaleed HaroonОценок пока нет

- CHAPTER 2 Part2 csc159Документ26 страницCHAPTER 2 Part2 csc159Wan Syazwan ImanОценок пока нет

- Configuration Guide - Interface Management (V300R007C00 - 02)Документ117 страницConfiguration Guide - Interface Management (V300R007C00 - 02)Dikdik PribadiОценок пока нет