Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Cheng, The Melancholy of Race

Загружено:

Ioana Miruna VoiculescuАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cheng, The Melancholy of Race

Загружено:

Ioana Miruna VoiculescuАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Melancholy of Race Author(s): Anne Anlin Cheng Source: The Kenyon Review, New Series, Vol.

19, No. 1, American Memory / American Forgetfulness (Winter, 1997), pp. 49-61 Published by: Kenyon College Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4337463 Accessed: 12/08/2010 15:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=kenyon. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Kenyon College is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Kenyon Review.

http://www.jstor.org

ANNE ANLIN CHENG THE MELANCHOLY OF RACE

If somethingis to stay in the memory,it must be burnedin: only that which neverceases to hurt stays in the memory.

NIETZSCHE,

On the Genealogy of Morals

In grief the worldbecomespoor and empty;in melancholia it is the ego itself.

FREUD,

"Mourningand Melancholia"

there any getting over race?

The answerwould seem to be negativein lightof the increasing frequency with which the "racecard"gets played.As the recent0. J. Simpsontrial and its accompanying rhetoricsuggest,racialrivalryis hardlyover. Indeed,it has acquired the peculiarstatusof a game wherewhat constitutesa winninghand has become identicalwith the handicap.Reappearing with the vagrancyof a joker, the race cardbringswith it a host of haunting questionsaboutthe value and perception of race and racialmattersin America.What does it mean that the deep woundof race in this countryhas come to be euphemizedas a card, a metaphorwhich acknowledgesthe rhetoricas such and yet simultaneously materializes raceinto a finiteobjectthatcan be dealtout, withheld,or trumped? Why the singularity of a card?Who gets to play? And what would constitute a "full deck"? Holding a "full deck" may imply some idealized version of multisubjectivity (i.e., the potentialto play the racecardandthe gendercardandthe immigrant card,etc.), but it also impliesa stateof mentalhealthandcompletion that renderssuch playing unnecessary in the first place. After all, one would a cardonly becauseone is alreadyoutsidethe largergame, for to play a "play"

49

50

THE KENYON REVIEW

card is to exercise the value of one's disadvantage, the liabilitythat is asset. The paradoxdoubles:the one who plays with a full deck not only need not play at all, but indeedhas no such "card" to play. Only thoseplayingwith less than a full deck need apply. Not only is liabilitytransmuted to assetandreformed yet againas liability, but the vocabulary of the card also reveals a conceptualization of health and of race and its abnormalities. pathologywhich underliesour very perceptions In Maxine Hong Kingston'sThe Woman Warrior, the narrator, after a vexed childhoodfull of racialand gendertraumas, tells her mother,"I've foundsome . . . where I don't catch colds or use places in this countrythat are ghost-free my hospitalization insurance.Here I am sick so often, I can barely work."1 In other words,I am most at home and fully myself when I am not at home andnot myself.The denigrated body gives rise to a hypochondriacal body, and the way for that body to imaginehealthis displacement, Yet the unheimlich. narrator's final deliverance can only play out its very impossibility.Her claim for such a ghost-freeand thrivingAmerica can only, within the context of her "bookof grievance," revealitself as endlessly haunted. "Getting over"the pathologiesof her childhoodand origin means,in a sense, never getting over those memories,so that health and idealizationturn out to be nothingmore thancontinualescape, and nothingless than the denial and pathologization of what one is. Meditatingon grief and the recollection of the dead, Freud posits a firm distinctionbetween mourningand melancholia.His 1917 essay on and Melancholia" "Mourning proposesmelancholiaas a pathologicalversion of mourning-pathological because,unlike the successful and finite work of mourning,the melancholiccannot "get over" loss; rather,loss is denied as loss and incorporated as partof the ego.2 In other words, the melancholicis so persistentand excessive in the remembrance of loss thatthat remembrance becomespartof the self. Thusthe melancholicconditionproducesa peculiarly thatincorporation ghostlyformof ego formation. Moreover, of loss still retains the statusof the originallost objectas loss; consequently, as Freudremindsus, andidentifyingwith the ghost of the lost one, the melancholic by incorporating takes on the emptinessof thatghostlypresenceand in this way participates in his/her own self-denigration. As a model of ego-formation (the incorporation as self of an excluded other),melancholia providesa provocative for how race in America, metaphor or more specificallyhow the act of racialization, works. While the formation of American culture may be said to be a history of legalized exclusions (Native Americans,African-Americans, Jews, Chinese-Americans, Japanese. . . ), it is, however,also a historyof misremembering Americans those denials. Becausethe American runs historyof exclusions,imperialism, andcolonization so diametrically of opposedto the equallyandparticularly Americannarrative culturalmemory in Americaposes a continuously liberty and individualism, those transgressions vexing problem:how to remember withoutimpedingthe

ANNE ANLIN CHENG

51

ethosof progress? How to burythe remnants of denigration anddisgustcreated in the name of progressand the formationof an "American identity"? Those subjected to abjection hoveron the edges of the dominant progressive narrative as objects at once ungrievedand unrelinquished. The invisible but corporealbody of Ralph Ellison's protagonist in InvisibleMan offers an excellent dramatization of the minorityas the object of white melancholia.In the openingscene, his is the invisiblebody thatthe whiteman literally"bumps into,"a forgottenghost who refusesforgetting,a lack-of-presence thatchokes the white man.3One might say the latterran into the bodily remnantof that which he has killed. We recall the novel's figureof progress,Mr. Norton, a white patronof the southernNegro college, who forgetsthe presenceof the InvisibleMan next to him in orderto monumentalize him, who cannotsee the youngblackmandrivinghim but sees in the other'sface his own "destiny." As a sponsorof Negro education, Mr. Nortonbuilds a monument to the "progress of historyas a mountingsaga of triumphs"4 on the ghostly bodies of young black men. With exampleslike this it is not difficultto conceive of dominant white identityin Americaas melancholic.In addition,ToniMorrison has, with a differentvocabulary,suggested that the Americanliterarycanon itself is a melancholiccorpus,proposing"an examinationand reinterpretation of the Americancanon, the foundingnineteenth-century works,for the 'unspeakable things unspoken';for the ways in which the presenceof Afro-Americans has shaped the choices, the language, the structure-the meaning of so much 5 The canon is a melancholiccorpusbecause of what it Americanliterature.' excludesbut cannotforget.The Afro-American presence,Morrison concludes, is "the ghost in the machine"(11). But what aboutthe minority?Can they be melancholictoo? If so, who and what are they forgettingin orderto remember? If we were to exhume,as Morrisonsuggests, the buriedbody in the heartof Americanliterature, what exactly is the natureof the "presence" that would be uncovered? Whatwould be the morphologyof ghostliness? Figuringthe minorityhas its difficulties.We understand that reparative and redemptivetendencies underlie much of the intellectual and material interests in "the minority."Yet as both the "race card" and the Kingston examples made clear, there is more than a little irony, if not downright in the effort to relabel as healthy a condition that has counterproductivity, been diagnosed,and kept, as sickly and aberrant. Melancholiacan be quite contagious. After all, it designates a condition of identity disorder where subjectandobjectbecomeindistinguishable fromone another. The melancholic object,madeneitherdeadnor fully alive, must experienceits own subjectivity as suspension, as excess and denigration-and in this way, replicate the melancholicsubject. With Kingston's narrator, we see the "good" cultural melancholic one who longs aftera visionof herselfthatexcludes par excellence: herself. This pathologicaleuphoria,however, merely assents to the dreamof multiculturalism: a utopianno-placewherethe pathologiesof race and gender

52

THE KENYON REVIEW

miraculouslyheal themselves. The very idea of the melting pot serves to celebrateassimilationwhile continuallyremarkingdifference.It is startling and we find overidealization how often in ethnic and immigrantnarratives euphoriain place of injury. of In Flower Drum Song, a classically bad Hollywood representation ethnic conditions, we actually get to see the minority, and specificallythe as illegality,thatwhichcame in but cannotbe admitted. celebrated immigrant, in the wake of the repealof the ChineseExclusionAct in 1943, this Produced and aims to promoteassimilation movie (as well as its Broadway predecessor) But whatexactly acrossAmerica.6 reflecta new, positive image of Chinatown is the face of this new citizenship?In the opening sequence,we find the two the young woman Mei Li and her father,stowed away on a main characters, boat that docks in San Francisco.When Mei Li offers to sing a "traditional creation"A HundredMillion Chinese song" (that Rodgersand Hammerstein on the streetsof San Franciscofor money, the fatherworriesabout Miracles") and warns, "It is unlucky to start in a the proprietyof such performance new countryby breakingthe law." The irony-that the old man is anxious brokenthe largerlaw aboutbreakingcivic law when he has alreadyflagrantly to of immigration-highlights a deeperdouble bind within "naturalization": survive, the strangerwho has violated the law must also be an ideal citizen, one who embodiesthe law. As he sails throughSan Francisco'sGoldenGate, becomesboththe illegalalienandthe modelminority. the fathersimultaneously illegal statusturnsout to be the very solutionto this national Furthermore, Mei Li finally lights moralityplay. In the finale, afterdespairand frustration, upon a solutionto free herself(andher real objectof affection)fromthe binds ceremony, of thatundesired marriage Onthe threshold of an arranged marriage. friends:"I must confess... my back to her newfoundAmerican she announces joy. In is wet!" She declares her own abject status with barely suppressed other words, only by exposing herself as an object of prohibitioncan she for love; Americandreamof the freedomof marrying achieve the particularly only by assentingto illegality can she hope to acquireideal citizenship.Her process, public confession and self-indictmentanticipatesthe naturalization where one acquirescitizenship in a rhetoricof rebirthpredicatedon selfwho renunciation ("Do you swear to give up..."). In fact, the one character in the movie-Helen the may be said to be an instanceof "good"assimilation bothherChineseheritage who seems to weave effortlesslytogether seamstress, andAmerican style-is also the classic odd womanout, whose "just-rightness" kind of kind of love, the "right" no one chooses. The choices of the "right" kindof girl in this movie turnout to be a lesson about beauty,and the "right" the rightkindof citizenship.And those who finallyattainthis nationalideal are by law. More thana hauntingconceptin preciselythose markedas prohibited subject"presentsa hauntedsubject.Minorityidentity America,the "minority of absence. Denigrationhas reveals an inscriptionmarkingthe remembrance andresuscitation. Not merelythe objectof dominant its formation conditioned

ANNE ANLIN CHENG

53

melancholia, the minority (in this case, literallyan impossible subject,the illegal alien) is also a melancholicsubject,except thatwhat she renouncesis herself. In the landscapeof grief, the boundary between subjectand object, the loser and the thing lost, poses a constantproblem.Even Freud's idea of a propermourning beginsto sufferfrommelancholic contamination. In orderfor propermourning to take place, one wouldhave to be already,somehow,"over it." For Freud,mourningentails,curiouslyenough,a forgetting: "...profound mourning.. does not recall the dead one."7Upon a closer look, the kind of healthy"lettinggo" Freuddelineatesgoes beyondmere forgettingto complete eradication. The successfulworkof mourning does not only forget,it reinstates the death sentence:

Just as the work of grief, by declaring the object dead and offering the ego the benefit of continuing to live, impels the ego to give up the object, so each single conflict of ambivalence,by disparaging the object, denigratingit, even as it were by slaying it, loosens the fixation of the libido to it. (emphasis added)8

Mourning implies the second killing off of the lost object. The denigration and murder of the beloved object fortifies the ego. Not only do we note that "health"here means rekilling a loss already lost, but we have to ask also how different is this in aim from the melancholic who hangs onto the lost object as part of the ego in order to live? That is to say, although different in method and technology (the mourner kills while the melancholic cannibalizes), the production of denigration and rejection, however re-introjected is concomittant with the production and survival of "self." The good mourner turns out to be none other than an ultrasophisticated, and more lethal, melancholic. In the landscape of racialization, such boundary confusion occurs on multiple levels: physical, sexual, ontological, terminological. In Carolivia Herron's disturbing novel ThereafterJohnnie, incest as a trauma of boundary is offered as a curse of slavery; in Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's experimental novel Dicte6e,the body of the narratoroften literally merges into the geography of division that is modern Korea, while the voice of the autobiographical subject remains indistinguishable from various forms of cultural dictation; in her wellknown essay "How It Feels to Be Colored Me," Zora Neale Hurston collapses the question of race into the question of specularity (who is watching; who is playing for whom). As James Clifford says, the question of boundary is the ethnic predicament. The point here is not to repathologize the minority, but to confront the more difficult question of what is a minority without his/her injury. Contemporary political activities and rhetoric designed to set matters right cannot really be effective, cannot escape relabeling those it aims

to liberate,until we recognizethatour very conceptionsof culturalhealthand arethemselves integrity preconditioned by whathavebeen deemedabnormal or

broken. In the way of Freudian logic, pathology defines health. Racial identity, as a moment of active self-perception, is almost always simultaneous with the

54

THE KENYON REVIEW

an instanceof othering.When Hurstonwrites,"I feel of another, racialization she refers most coloredwhen I am thrownagainsta sharpwhite background," of blackness,butof whitenessas well, each defining not only to the constitution in Passing knows all too Or, as Nella Larsen'snarrator the other'spathology.9 well, race is the companythat you keep. It shouldbe clear by now that race itself lives in Americaas a melancholic presence.Morespecifically,racialization-as an act of self-constitution the Other-must be conceived of as a throughdenying and re-assimilating wholly melancholicactivity. The rhetoricof compensation,which attempts of the throughinversion,neglects the organization to reverse discrimination the nor can it accommodate activity that went into producingdiscrimination, physical effects of those wounds. There is a possibilitythat we may not be unscathedsubject underthe dirty bandageof able to retrievean unmarked, racism. As we saw with Flower DrumSong, Mei Li's presence was always as such in her final acquisitionof a and re-marked markedas transgression, new homeland.Similarly,we are all too painfullyfamiliarwith popularracial those thanidentifying withinourpublicsphere,butrather fantasiesthatcirculate images("We yet againor simplydenyingthose clearlytroublesome stereotypes to go on to the more aren'tlike that!"),it seems more fruitfuland important complex question of how melancholicracializationworks. To propose that the minoritymay have been profoundlyaffectedby racial fantasiesis not to task the more important but to perform lock him/herback into the stereotypes, operations-and seductions-produced the deeperidentificatory of unraveling by those projections. If the melancholicminorityis busy forgettingherself, with what is she identifying?We have all heardthe wisdom that women and minoritieshave internalizeddominantcultural demands,but do we really know what that It is a dangerous question means?Wheredoes desirecome into this equation? to ask whatdoes a minoritywant.Whenit comes to politicalcritique,it seems as if desire itself may be what the minorityhas been enjoined to forget. In the storyof a French play M. Butterfly, David HenryHwang'saward-winning that his Chinese mistress discovers who after ten years diplomat(Gallimard) what remains a glaringlymissing (SongLiling)was notonly a spy butalso man, has M. Butterfly now desires. By of Song's from the play is an entertainment sexual fantasies; fantasies facilitate how racial text of becomean almost-classic has been the play's exposureof the consistent centralto muchcriticalattention in white males society. Indeed,the play's fundamental Asian of emasculation succeededbecauseof Gallimard's sexual deception is that Song's assumption racialstereotypes about"theEast."Yetas an exposeof sexualintrigueandracial objectiveto begs the question:aside fromhis professional fantasy,M. Butterfly And his in investment disguise? a have does personal Song seduce Gallimard, what would it meanfor the politicalagendaof the play if he did? In the three momentsof the play whenwe mighthavehintsof Song's own privatefantasies, Chin asks why Song whenComrade we aregreetedwith silencesanddeferrals:

ANNE ANLIN CHENG

55

remainsin disguise when alone; when the judge questionsSong's incredible acting ability;and when Gallimard questionsSong's motivation.In all three brief instances,Song's answer comes in the form of ellipses and pauses, as thoughhis desire can only be pronounced as unutterability. Significantly, the play can see Song only as the object of Gallimard's desire or as the critic of that desire. It is as though to articulate Song's desire would renderhim less "cool"or jeopardizehis positionas a propercritic of Westernracialfantasies. In otherwords,Song must not want.His inauthentic performance mustremain inauthentic in orderto guarantee the authenticity of his critique. The notion that cultural assimilationalways requires certain acts of personal relinquishment and even disguise is a common one, easily and understood conventionally as the priceof "fitting in."Think,for example,of the long literary with deception.Postcolonial alignment of "passing" theoristHomi Bhabhaoffers us some insights into the connectionbetween assimilationand falsehood.He identifies"mimicry" as a colonial, disciplinaryinjunctionand device, one thatis nonethelessdoomedto fail. He explains,"colonialmimicry is the desire for a reformed,recognizableOther,as a subjectof a difference

that is almost the same, but not quite." 10 By this account, the colonized finds

him/herself in the positionof melancholically echoingthe master,incorporating both the master and his own denigration.What we have been calling the "internalization of the other,"Bhabhaattributesto authoritative injunction. Such injunctionto mime the dominantcan be seen from images such as the Indianservantdressed as the Englishmanto the colonial institutionalization of languageitself. We see here sophisticated versionsof the "priceof fitting in." To put it crudely,Bhabhahas located the social injunctionto assimilate and thatinjunction's built-infailure.The colonizedsubjectmust be disguised, mimed,as almostthe same, but not quite.His/herincompleteimitationin turn serves as a sign of assimilativefailure,the failureof authenticity. The concept of melancholicracialization, however, implies that assimilation may be more intimatelylinked to identitythan a mere consequenceof the dominantdemandfor sameness.In melancholia,assimilation("actingliko an internalizedother")is a fait accompli, part and parcel of ego formation for the dominantand the minority,except that with the latter,such doubling is seen as somethingfalse ("actinglike someone you're not").The notion of racial authenticityis thus finally a culturaljudgmentwhich itself disguises the identificatory assimilation that has already taken place in melancholic "I am constituted racialization: by an otherwho finallymust, and mustnot, be me." The story of M. Butterfly suggeststhat deceptionmight be more deeply affective than merely facilitatingassimilation;rather,"passing"may share a similarlogic with the activityof identityitself. Nearthe end of the profoundly play Song seems to have forgottenthe terms of his own game. We see him never really loved me? proteststartlingly and tellingly, "So-you [Gillimard] Only when I was playing a part?""lThe blindness of that questionreveals Song as havingbeen seducedby his own mise-en-scene. The failureof Song's

56

THE KENYON REVIEW

deceptioncomes from this plunge into the realityof that deception.And that a sense of "thereal failureof authenticity has the very specificeffect of creating self": Song cries, "I'm your butterfly... it was always me."12 The seduction of authenticity turnsout to promisenothingless thanthe possibilityof a pure

self: ".. . it was always me."

In his introduction to Abraham and Torok'sThe Wolf Man'sMagic Word (itself a responseto Freudon melancholia), JacquesDerridasimilarlyimplies to an act of identification: that the disguise may be fundamental

The first hypothesis of The Magic Word... supposes a redefinitionof the Self (the systems

of introjections) and of the fantasy of incorporation....

The more the self keeps the foreign element as a foreigner inside itself, the more it excludes it. The self mimesintrojection.But this mimicry with its redoubtable logic depends on clandestinity. Incorporation operates clandestinely with a prohibitionit neither accepts nor transgresses. (underliningadded)'3

The "foreigner inside"lives as the "self."To raciallyassimilate(in the senses of blendingin and takingin) implies an act of public and subjectivedisguise: not only the disguiseof the self in the traditional sense of "takingit," but also in the deepersense of remakingthe self throughthe other,a profoundlyselfact. WhatI called the pureself thatSong in M. Butterfy assertsis constituting figuredafterthe master.Song does not come to power in the end nor assume the success of his politicalcritiqueby acquiringsome authentic Chinesemale identity.On the contrary, he does so by donningan Armanisuit and adopting the colonial voice: "Youthink I could've pulled this off if I wasn't full of pride?. . . It took arrogance, really-to believe you can will . . . the destiny of 14One might say Song has not only learnedhow to be with a white another." man, but also how to be the white man. The difficultlesson of M. Butterfly thereforeis not the existenceof fantasystereotypesas the playwrighthimself idea thatfantasystereotypes assertsin the Afterword, but the more disturbing may be the very ways in whichwe come to know and love someone..., come to know and love ourselves.

Melancholia has thus seeped into every cornerof our landscape.Is there any getting over it? First it seems more importantthan ever to recognize that identity built on loss is symptomaticof both the dominant and the marginalized. Second,at the risk of speakinglike a true melancholic,perhaps minoritydiscoursemight prove to be most powerful when it resides within the consciousness of melancholiaitself, when it can maintaina "negative betweenneitherdismissing,nor sentimentalizing the minority.Let capability" us returnto the hauntingsof InvisibleMan. Ellison's politicalcritiquein that of a self-reflexivemelancholia, novel seems preciselythe dramatization a man whose invisibilityaffects the marginas well as the center:

ANNE ANLIN CHENG

57

I am invisible.... Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrorsof hard,distortingglass. When they approachme they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination.... 15

In thathall of mirrors, who distortswhom?As muchas racialblindnessrenders the narrator invisible, his invisibility also reflects emptiness back on those gazers as well. If he has been assimilatedonly throughhis invisibility,then he also rendersdissimilarand strangethe status of their visibility. Here we have the potentialfor a kind of subversiveassimilation,a kind of mimetic dissimulation inherentin, thoughdifferentlyinflectedby, Bhabha's"discourse of mimicry." The phantasm of the narrator's invisibilityimitatesthe phantasm that is mainstream society. The character who embodiesthis strategyof imitationis of course the phantasmatic figure of Rinehart.Literallythe real invisible man in the text, Rinehartnever appears-except as pure appearance:Rinehartthe runner, Rine the gambler,Rine the briber,Rine the lover, pimp, and reverend.He stands as the figure of a figure. To try to locate Rinehart's"true"identity would be to miss the lesson of Rinehart:who you are depends on whom you are talking to, which community you are in, and who is watching your performance. Embodyingdissimulativepotentials,glaringly visible in his invisibility,Rinehartoperatesand structures a networkof connectionsin Harlem fromreligionto prostitution to the law. A mandefinedby costumesand and "insider," props,he is at once the ultimate"outsider" makingvisible the of identityandperverting the lines of power-or at least,exposing contingency As a parablefor plurality, as a continually poweras positionality. re-signifiable indisign, Rinehartcritiques the mainstreamideal of an uncompromising viduality. Rinehart as an event of visual performance demonstrates firstthatthe act of identification is dependent on representation, and thus drawsour attention to the power dynamics of viewer and spectatorship; second, that the act of representation involves simultaneously,on a deeper level, an act of disidentification. To impersonate Rinehart was is to becomeRinehart: "Something and profoundly... being mistakenfor him.., my workingon me [the narrator], entirebody startedto itch, as thoughI had just been removedfrom a plaster cast ... you could actuallymake yourself anew."16 Yet even as the narrator celebratesa rebirththroughhis disguise, he suffers from a kind of identity "Whoactuallywas who?"Becominga re-signable aphasia,askingrepeatedly, sign pays a priceof its own. "It"is notjust a costume,as Song in M. Butterfly has foundout. The site of identification is presented as difficultand ambivalent preciselybecause thereis a cost in every identitystaging. This liberation is thus provisional, if not downright shattering.By the narrator arrivesnot at an identity,but the phantasm impersonating Rinehart, that is the mode of identification. To follow Rinehartism is to plunge into the

very heart of racial melancholia:

58

THE KENYON REVIEW

So I'd accept it, I'd explore it, rine and heart. I'd plunge into it with both feet and they'd gag. Oh, but wouldn't they gag.... Yes, and I'd let them swoller me until they vomited or burst wide open. Let them gag on what they refuse to see.'7

literalizesthe melancholic conditionof race in America:we gag on "Gagging" what we refuseto see. Americancultureis continuallyconfrontedby ghosts it can neither spit out nor swallow. Rinehart,the "SpiritualTechnologist," 18 recommends a remedy for that social malady: "Behold the Invisible," suggesting that only by recognizinginvisibilitycan we begin to understand the conditionsof visibility.EarlierI askedwhatis the statusof the "presence" to "real"Africanwhich Toni Morrisonwants us to uncover.Is she referring of African-American presence?I propose Americanpresenceor the phantasm of and phantomization thatthe answercan only be the latter.The racialization exist to produce"American" presence.The always ghostly African-Americans in Americanliterature implies that the entire presenceof African-Americans of configuring visibility (who is white, who is black; process of racialization, who is visible, who is not), must be consideredas itself melancholic.The act of delineatingabsence preconditionspresence.Race in America is thus "stuck"withinthe Moebius stripof inclusionand exclusion:an identification thatworksitself out by on dis-identity.It is a fear of contamination predicated a remembering of a forgettingthat cannotbe remembered. contamination, thanbeingmadeto witnessthe simultaneAnd nothingis moredisturbing for a moment,is perhaps why the theater of ity of thatduality.This, to sidetrack made AnnaDeveareSmithholds suchresonance. Eachcharacter is constituted, real for us, by his/hercounterdefinition to another, andthe tablekeeps turning. the discomfort of Smith'sperformances understands Anyone who has partaken of being made to watch the fine line between speakingfor, speakingas, and one sees on a single speaking against. In Smith's theaterof incorporation, conflictualviews betweenracializedpeoples stage the agon, the multifaceted, andthe inconsolability of eachof theirpositions.One (even withinindividuals), gets a feeling too that there will never be enoughjustice, enough reparation, enoughguilt, pain, or angerto make up for the racialwoundscleaved into the as Americanpsyche-remembered by boththe dominant andthe marginalized it is itself. With Smith'speculiarbrandof impersonation, incommensurability in the bodilyoccupation as if only in imitation, of the other,thatwe come to see an alternative to the trapsof representation. Thatis, representation paradoxically has frequentlyand rightly been criticized for its colonizing potentials.But Smith's art suggests that representation, mimicryeven, may be employed as a form of performative counteroccupation, wherebythe act of placingoneself in the other'splace exposes one's vulnerability to thatperformed other.More polyphonicmonologuedramatizesthe psychical profoundly,her paradoxical truththat to speak is to speak the other. InvisibleMan hints thatthe firstsolutionto thatmelancholicconditionis not to recovera presencethatnever was, but to recognizethe disembodiment

ANNE ANLIN CHENG

59

that is both the masterand the slave. Rinehart'smetaphoricdisembodiment hallucination, the scene of own epiphanic becomesliteralizedin the narrator's castration. In a state of neitherdreamingnor waking,he confrontsthe groups histories brandsof incorporative and their particular that he has encountered and ideologies:

... I lay the prisonerof a group consisting of Jack and Emerson and Bledsoe and Norton and Ras and the school superintendent.... they were demandingthat I return to them and were annoyed with my refusal. "No," I said. "I am through with all your illusions and lies..." But now they came forwardwith a knife... and I felt the brightred pain as they took the two bloody blobs and cast them over the bridge, and out of my anguish I saw them curve up and catch beneath the apex of the curving arch of the bridge, to hang there, dripping down throughthe sunlight into the dark red water. "Now you're free of illusions," Jack said, pointing to my seed wasting upon the air. "How does it feel to be free of one's illusions?" And now I answered, "Painfuland empty... But look... there's your universe, and that drip-dropupon the water you hear is all the history you've made, all you're going to

make...."

19

The narrator'sdismemberment, his scattered, castrated ego becomes the resis-

andsignifyingprocesses.By tryingto recruit tanceagainstgroupconsolidations him to do so, the as a mirrorimage of themselves,by castrating the narrator the very loss that they instigate. If incorporate various social organizations then historywill be structured by thatbrutalization. historyenactsdenigration, that "to be free of illusions and lies" is viscerally This scene demonstrates but it also imagines that freedommight occur in the very place brutalizing, of that rupture. or social libthatfreedomcomesnot fromhistorical This scene speculates individual of identity("painful eration,but specificallyfrom the renouncement and empty"),because the vocabularyof freedomitself can be deployed by by the rhetoricof the Brotherhood). the rhetoricof enslavement(as illustrated and free "Tobe of illusions"paradoxically cruciallymeans to be free of the hasbeen searching the book,the narrator Throughout ideologiesof authenticity. The only vision as well as communal identification. for visibility,individualism, of pain of individualism,however, comes from the state of disappearance, and emptiness-a shattered ratherthanreconstituted subject.In that scene of invisibilityhas been theorizedas a condition castrationand relinquishment, of disembodimentand abstraction,as an escape from "illusions."Ellison but in intrasubjective individualism, locates identity,not in uncompromising and violently. that are intersubjectively experienced negotiations-negotiations The resolutionof InvisibleMan remainsfar fromcertain.Whatis the "socially will play by the end of the novel? The responsiblerole" that the narrator or particular narrative has offeredus more questionsthanany final affirmation course of action. The narratorinforms us: "So it is now I denounce and

6o

THE KENYON REVIEW

defend... I condemnand affirm,say no and say yes, say yes and say no.... So I approachit throughdivision."20Ellison's politics in this work offer us descriptionratherthan prescription. embodies its inverse: exclusion. InvisibleMan remains "Community" wary of the very groupideologies that "create" and isolate African-American in the firstplace. As the enclave that protectsbut also marginalcommunities izes, Harlemis not free from that"soul-sickness." The narrator tells us thathe has been "as invisibleto Mary [the nurturing 'mother'in the heartof Harlem] 2' When he asks of Clifton's death, as [he] had been to the Brotherhood." "Whydid he choose to plungeinto nothingness, into the void of faceless faces, of soundlessvoices, laying outside history,"22 he anticipateshis own falling underground, significantlyon the edge betweenHarlemand the mainstayof the city. InvisibleMan collapses the literalquestionof "whereyou stand"into and political questionof "whereyou stand,"and exposes its the metaphoric The discourseof identityfostersdivisionand dis-identification positionality. as well. Consequently, Ellison's political thesis has always seemed to me more radical than minoritypolitics find comfortable.It is radical in its profound of group ideology and of communalpossibilities.The political undermining platform of Invisible Man,contrary to the appealof the representative novel and its ethnicbildung,relies not on identity-because the protagonist neverarrives at one-but on the nonexistence of identity,on invisibilitywith its assimilative and dissimulative possibilities.Yet this place of political discomfortprovides the most intenseexamination of what it meansto adopta political stance. Wordsfrom the invisible man remainto hauntus: "You carrypart of

your sickness with you" (575). You carry the foreigner inside. This malady

of doubleness,I argue,is the melancholyof race, a dis-ease of location and that cleaves and cleaves to the memory,a persistentfantasyof identification and the master. marginalized

NOTES

'Maxine Hong Kingston, The WomanWarrior:Memoir of a Girlhood Among Ghosts (New York: Vintage, 1979) 108. 2Sigmund Freud, "Mourningand Melancholia,"Collected Papers: Vol.IV (London: Hogarth, 1953). 3Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (New York: Vintage, 1990) 4. 4Ellison 36. 5Toni Morrison, "UnspeakableThings Unspoken: The Afro-AmericanPresence in American Literature," Michigan QuarterlyReview 28 (Winter 1989): 11. 6Althoughthe Chinese Exclusion Act was repealedin 1943, it was not until the Immigration Act of 1965 that the national-quotasystem on Chinese immigrantswas finally lifted. Thus Flower Drum

ANNE ANLIN CHENG

6I

Song was produced, significantly, at a time when Chinese immigrationpatterns to the U.S. were on the brink of great changes. 7Freud 153. 'Freud 169. 9Zora Neale Hurston, "How It Feels to Be Colored Me," I Love Myself When I Am Laughing... And Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive (New York: The Feminist Press, 1979) 154. l0Homi Bhabha, "Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse," October 28 (Spring 1984): 126. "David Henry Hwang, M. Butterfly(New York:Penguin Books, 1986) 89.

12Hwang 89. 13Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok, The Wolf Man's Magic Word:A Cryptonymy,trans. Nicholas Rand (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1986), xv, xvii. 14Hwang 85.

15Ellison 3.

16Ellison 498-99. 17Ellison 508. 18Ellison 495.

19Ellison 569-70. 20Ellison 580.

21Ellison 57 1.

22Ellison 441.

Вам также может понравиться

- Decolonial Mourning and the Caring Commons: Migration-Coloniality Necropolitics and Conviviality InfrastructureОт EverandDecolonial Mourning and the Caring Commons: Migration-Coloniality Necropolitics and Conviviality InfrastructureОценок пока нет

- Imperialist NostalgiaДокумент17 страницImperialist NostalgiaTabassum Zaman100% (1)

- Anibal Quijano - Coloniality PDFДокумент48 страницAnibal Quijano - Coloniality PDFJorge GonzalesОценок пока нет

- 01 Quijano and Wallerstein Americanity As A ConceptДокумент9 страниц01 Quijano and Wallerstein Americanity As A ConceptGilberto Florencio FariaОценок пока нет

- Sara Ahmed, Lancaster University: Communities That Feel: Intensity, Difference and AttachmentДокумент15 страницSara Ahmed, Lancaster University: Communities That Feel: Intensity, Difference and AttachmentClaire BriegelОценок пока нет

- 170 Gilroy - Ethnicity and Postcolonial TheoryДокумент4 страницы170 Gilroy - Ethnicity and Postcolonial TheoryChalloner Media0% (1)

- Avtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismДокумент7 страницAvtar Brah - Questions of Difference and International FeminismJoana PupoОценок пока нет

- Mariano Mestman - The Last Sacred Image of The Latin American RevolutionДокумент22 страницыMariano Mestman - The Last Sacred Image of The Latin American RevolutionGavin MichaelОценок пока нет

- Ahmed Sociable HappinessДокумент4 страницыAhmed Sociable Happinessbsergiu2Оценок пока нет

- Cultural Studies: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationДокумент21 страницаCultural Studies: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationChiniAquinoОценок пока нет

- I. Testimonio: The Witness, The Truth, and The InaudibleДокумент2 страницыI. Testimonio: The Witness, The Truth, and The InaudibleMachete100% (1)

- Roderick Ferguson, Aberrations in Black (Intro + Ch. 4)Документ33 страницыRoderick Ferguson, Aberrations in Black (Intro + Ch. 4)Michael LitwackОценок пока нет

- Speculative Futures - Race in WatchmenДокумент21 страницаSpeculative Futures - Race in WatchmenmejilsaОценок пока нет

- Depressive Realism: An Interview With Lauren Berlant: Earl MccabeДокумент7 страницDepressive Realism: An Interview With Lauren Berlant: Earl Mccabekb_biblio100% (1)

- World Traveling, Playfulness - LugonesДокумент18 страницWorld Traveling, Playfulness - LugonesElisaОценок пока нет

- Tobias Hübinette & Catrin Lundström - Sweden After The Recent ElectionДокумент12 страницTobias Hübinette & Catrin Lundström - Sweden After The Recent ElectionPashaAliОценок пока нет

- Mignolo Interview PluriversityДокумент38 страницMignolo Interview PluriversityJamille Pinheiro DiasОценок пока нет

- Rappaport Utopias InterculturalesДокумент8 страницRappaport Utopias InterculturalesIOMIAMARIAОценок пока нет

- Killing Joy - Feminism and The History of Happiness - Sarah AhmedДокумент25 страницKilling Joy - Feminism and The History of Happiness - Sarah AhmedGabriela GaiaОценок пока нет

- Maldonado-Torres Outline of Ten Theses-10.23.16Документ37 страницMaldonado-Torres Outline of Ten Theses-10.23.16Charlee Chimali100% (2)

- An Accented Cinema - Hamid NaficyДокумент5 страницAn Accented Cinema - Hamid Naficysebastian_rea_10% (2)

- Coloniality - at - Large - Chap1Документ24 страницыColoniality - at - Large - Chap1Camila WolpatoОценок пока нет

- Unmournable Bodies - The New Yorker Teju ColeДокумент4 страницыUnmournable Bodies - The New Yorker Teju ColeGaby ArguedasОценок пока нет

- Walter Mignolo - Who Speaks For The Human in Human RightsДокумент18 страницWalter Mignolo - Who Speaks For The Human in Human RightsLucas SantosОценок пока нет

- LOVE Art Politics Adrienne Rich InterviewsДокумент10 страницLOVE Art Politics Adrienne Rich Interviewsmadequal2658Оценок пока нет

- Deborah Martin - Feminine Adolescence and Transgressive Materiality in The Films of Lucrecia Martel PDFДокумент11 страницDeborah Martin - Feminine Adolescence and Transgressive Materiality in The Films of Lucrecia Martel PDFMaría BelénОценок пока нет

- Savransky - The Bat Revolt in Values A Parable For Living in Academic RuinsДокумент12 страницSavransky - The Bat Revolt in Values A Parable For Living in Academic RuinsAnonymous slVH85zYОценок пока нет

- ColonialityDiasporas HRДокумент12 страницColonialityDiasporas HRHoracio CastilloОценок пока нет

- Buell ToxicDiscourseДокумент28 страницBuell ToxicDiscoursesourloulouОценок пока нет

- Center For Latin American and Caribbean Studies, University of Michigan, Ann ArborДокумент20 страницCenter For Latin American and Caribbean Studies, University of Michigan, Ann ArborfernandabrunoОценок пока нет

- SILVA, Denise Ferreira Da. After It - S All SaidДокумент4 страницыSILVA, Denise Ferreira Da. After It - S All SaidCamila VitórioОценок пока нет

- Gloria E. Anzalduas AutohistoriaДокумент18 страницGloria E. Anzalduas AutohistoriaEmma TheuОценок пока нет

- Hall-Constituting An ArchiveДокумент5 страницHall-Constituting An ArchivefantasmaОценок пока нет

- Black Nature The Question of RaceДокумент18 страницBlack Nature The Question of RaceRicardo DominguezОценок пока нет

- Jorge Marcone - de Retorno A Lo Natural: La Serpiente de Oro, La "Novela de La Selva" y La Crítica EcológicaДокумент11 страницJorge Marcone - de Retorno A Lo Natural: La Serpiente de Oro, La "Novela de La Selva" y La Crítica EcológicaluyalanОценок пока нет

- Melancholic Ghosts in Monique Truongs The Book of Salt-LibreДокумент20 страницMelancholic Ghosts in Monique Truongs The Book of Salt-LibreMaura ColaizzoОценок пока нет

- Culture of Class by Matthew B. KarushДокумент29 страницCulture of Class by Matthew B. KarushDuke University Press100% (1)

- Geopolitics of Sensing and KnowingДокумент9 страницGeopolitics of Sensing and Knowingfaridsamir1968Оценок пока нет

- Coloniality of Power and De-Colonial ThinkingДокумент14 страницColoniality of Power and De-Colonial Thinkingandersonjph1999Оценок пока нет

- Iyko Day - Being or NothingnessДокумент21 страницаIyko Day - Being or NothingnessKat BrilliantesОценок пока нет

- 13 3friedman PDFДокумент20 страниц13 3friedman PDFfreedownloads1Оценок пока нет

- True Life, Real Lives. Fassin, DidierДокумент16 страницTrue Life, Real Lives. Fassin, DidierDeissy PerillaОценок пока нет

- Su, Writing The Melancholic, Kristeva's Black SunДокумент29 страницSu, Writing The Melancholic, Kristeva's Black SundiapappОценок пока нет

- Sharon W. Tiffany - Paradigm of Power: Feminist Reflexion On The Anthropology of Women Pacific Island SocietiesДокумент37 страницSharon W. Tiffany - Paradigm of Power: Feminist Reflexion On The Anthropology of Women Pacific Island SocietiesТатьяна Керим-ЗадеОценок пока нет

- Ngugi Wa Thiong'o (1998) - Decolonising The MindДокумент4 страницыNgugi Wa Thiong'o (1998) - Decolonising The MindExoplasmic ReticulumОценок пока нет

- (Halberstam, 2015) in Human Out HumanДокумент41 страница(Halberstam, 2015) in Human Out HumanJinsun YangОценок пока нет

- Laclau, Mouffe and Zournazi - Hope, Passion and The New World Order. Mary Zournazi in CДокумент6 страницLaclau, Mouffe and Zournazi - Hope, Passion and The New World Order. Mary Zournazi in Ctomgun11Оценок пока нет

- (Critical South) Néstor Perlongher - Plebeian Prose (2019, Polity) - Libgen - LiДокумент322 страницы(Critical South) Néstor Perlongher - Plebeian Prose (2019, Polity) - Libgen - LiMiltonPetruczokОценок пока нет

- Dossier Lelia Gonzalez AmefrikansДокумент5 страницDossier Lelia Gonzalez AmefrikansNicole MachadoОценок пока нет

- Notes Epistemologies of The SouthДокумент7 страницNotes Epistemologies of The SouthNinniKarjalainenОценок пока нет

- The Problematics of Race and The Eternal Quest For Freedom: A Postcolonial Reading of Toni Morrison's Novels Within The Context of The Black Lives Matter ProtestsДокумент10 страницThe Problematics of Race and The Eternal Quest For Freedom: A Postcolonial Reading of Toni Morrison's Novels Within The Context of The Black Lives Matter ProtestsIJELS Research JournalОценок пока нет

- Wynter Ceremony Must Be Found After HumanismДокумент53 страницыWynter Ceremony Must Be Found After HumanismDavidОценок пока нет

- Fanon and Améry - Theory, Torture and The Prospect of Humanism PDFДокумент18 страницFanon and Améry - Theory, Torture and The Prospect of Humanism PDFderoryОценок пока нет

- Border Thinking and Disidentification PoДокумент18 страницBorder Thinking and Disidentification PoBohdana KorohodОценок пока нет

- The Postsocialist Missing Other' of Transnational Feminism?Документ7 страницThe Postsocialist Missing Other' of Transnational Feminism?sivaramanlbОценок пока нет

- Critical Autobiography A New GenreДокумент13 страницCritical Autobiography A New GenrerobertoculebroОценок пока нет

- Joanna Page - Folktales and Fabulation in Lucrecia Martel's FilmsДокумент18 страницJoanna Page - Folktales and Fabulation in Lucrecia Martel's FilmsMaría BelénОценок пока нет

- We Are Ugly But We Are Here EssayДокумент2 страницыWe Are Ugly But We Are Here EssayFernandoОценок пока нет

- STOLER. Colonial Archives and The Arts of GovernanceДокумент24 страницыSTOLER. Colonial Archives and The Arts of GovernanceRodrigo De Azevedo WeimerОценок пока нет

- Muñoz - No Es Fácil - Notes On The Negotiation of Cubanidad and Exilic Memory in Carmelita Tropicana's Milk of AmnesiaДокумент7 страницMuñoz - No Es Fácil - Notes On The Negotiation of Cubanidad and Exilic Memory in Carmelita Tropicana's Milk of AmnesiaMariana OlivaresОценок пока нет

- Why Do Humans Reason SperberДокумент55 страницWhy Do Humans Reason SperberhuseinkОценок пока нет

- Stephen C, Levinson, Language and SpaceДокумент31 страницаStephen C, Levinson, Language and SpaceIoana Miruna VoiculescuОценок пока нет

- The Absorption Hypothesis. LuhrmannДокумент13 страницThe Absorption Hypothesis. LuhrmannIoana Miruna VoiculescuОценок пока нет

- Stephen C, Levinson, Language and SpaceДокумент31 страницаStephen C, Levinson, Language and SpaceIoana Miruna VoiculescuОценок пока нет

- Flyvbjerg, Habermas and Foucault: Thinkers For Civil Society?Документ25 страницFlyvbjerg, Habermas and Foucault: Thinkers For Civil Society?Ioana Miruna VoiculescuОценок пока нет

- Beyond The Brain: by Tanya Marie LuhrmannДокумент7 страницBeyond The Brain: by Tanya Marie LuhrmannIoana Miruna VoiculescuОценок пока нет

- Zigon - On LoveДокумент15 страницZigon - On LoveIoana Miruna VoiculescuОценок пока нет

- Hallucinations and Sensory Overrides: T. M. LuhrmannДокумент15 страницHallucinations and Sensory Overrides: T. M. Luhrmannjcrosby77Оценок пока нет

- Fisker Karma - Battery 12V Jump StartДокумент2 страницыFisker Karma - Battery 12V Jump StartRedacTHORОценок пока нет

- Subtotal Gastrectomy For Gastric CancerДокумент15 страницSubtotal Gastrectomy For Gastric CancerRUBEN DARIO AGRESOTTОценок пока нет

- Temperature Measurement: Temperature Assemblies and Transmitters For The Process IndustryДокумент32 страницыTemperature Measurement: Temperature Assemblies and Transmitters For The Process IndustryfotopredicОценок пока нет

- Math 10 Week 3-4Документ2 страницыMath 10 Week 3-4Rustom Torio QuilloyОценок пока нет

- RF Based Dual Mode RobotДокумент17 страницRF Based Dual Mode Robotshuhaibasharaf100% (2)

- Laminar Premixed Flames 6Документ78 страницLaminar Premixed Flames 6rcarpiooОценок пока нет

- Majan Audit Report Final2Документ46 страницMajan Audit Report Final2Sreekanth RallapalliОценок пока нет

- Army Public School No.1 Jabalpur Practical List - Computer Science Class - XIIДокумент4 страницыArmy Public School No.1 Jabalpur Practical List - Computer Science Class - XIIAdityaОценок пока нет

- RL78 L1B UsermanualДокумент1 062 страницыRL78 L1B UsermanualHANUMANTHA RAO GORAKAОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Cobit Framework - Week 3Документ75 страницIntroduction To Cobit Framework - Week 3Teddy HaryadiОценок пока нет

- Centric WhitepaperДокумент25 страницCentric WhitepaperFadhil ArsadОценок пока нет

- The Origin, Nature, and Challenges of Area Studies in The United StatesДокумент22 страницыThe Origin, Nature, and Challenges of Area Studies in The United StatesannsaralondeОценок пока нет

- The Two Diode Bipolar Junction Transistor ModelДокумент3 страницыThe Two Diode Bipolar Junction Transistor ModelAlbertoОценок пока нет

- LG) Pc-Ii Formulation of Waste Management PlansДокумент25 страницLG) Pc-Ii Formulation of Waste Management PlansAhmed ButtОценок пока нет

- Datasheet Brahma (2023)Документ8 страницDatasheet Brahma (2023)Edi ForexОценок пока нет

- P4 Science Topical Questions Term 1Документ36 страницP4 Science Topical Questions Term 1Sean Liam0% (1)

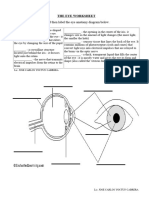

- The Eye WorksheetДокумент3 страницыThe Eye WorksheetCally ChewОценок пока нет

- A Guide To Funeral Ceremonies and PrayersДокумент26 страницA Guide To Funeral Ceremonies and PrayersJohn DoeОценок пока нет

- The Life Cycle of Brent FieldДокумент21 страницаThe Life Cycle of Brent FieldMalayan AjumovicОценок пока нет

- QFW Series SteamДокумент8 страницQFW Series Steamnikon_fa50% (2)

- Physical Characteristics of SoilДокумент26 страницPhysical Characteristics of SoillfpachecoОценок пока нет

- Workshop Manual: 3LD 450 3LD 510 3LD 450/S 3LD 510/S 4LD 640 4LD 705 4LD 820Документ33 страницыWorkshop Manual: 3LD 450 3LD 510 3LD 450/S 3LD 510/S 4LD 640 4LD 705 4LD 820Ilie Viorel75% (4)

- Chapter 4 PDFДокумент26 страницChapter 4 PDFMeloy ApiladoОценок пока нет

- GRADE 302: Element Content (%)Документ3 страницыGRADE 302: Element Content (%)Shashank Saxena100% (1)

- Origins - and Dynamics of Culture, Society and Political IdentitiesДокумент4 страницыOrigins - and Dynamics of Culture, Society and Political IdentitiesJep Jep Panghulan100% (1)

- PresentationДокумент6 страницPresentationVruchali ThakareОценок пока нет

- Hamza Akbar: 0308-8616996 House No#531A-5 O/S Dehli Gate MultanДокумент3 страницыHamza Akbar: 0308-8616996 House No#531A-5 O/S Dehli Gate MultanTalalОценок пока нет

- Opentext Documentum Archive Services For Sap: Configuration GuideДокумент38 страницOpentext Documentum Archive Services For Sap: Configuration GuideDoond adminОценок пока нет

- Chapter 17 Study Guide: VideoДокумент7 страницChapter 17 Study Guide: VideoMruffy DaysОценок пока нет

- University Grading System - VTUДокумент3 страницыUniversity Grading System - VTUmithilesh8144Оценок пока нет