Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Notes On John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism

Загружено:

Jonathan MenesesОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Notes On John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism

Загружено:

Jonathan MenesesАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism Chapter 2, What utilitarianism is Objections to utilitarianism that Mill claims depend on misunderstanding the

view: 1. "Utility is opposed to pleasure." No, it is "pleasure itself, together with exemption from pain." 2. Utility is pleasure "in its grossest form." No, Mill recognize that distinctions can and should be made: a. between the "circumstantial [that is, extrinsic] advances" and the "intrinsic nature" of pleasure. For example, some mental pleasures are superior to bodily ones by virtue not of their intrinsic nature, but of their "greater permanency, safety, uncostliness, etc." b. between the quantity and quality of pleasure. i. One tells "which is the best having of two pleasures" by appealing to "the judgment of those who are qualified by knowledge of both, or, if they differ, that of the majority among them." ii. "It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied." 3. Happiness cannot be the end because "it is unattainable." If by happiness is meant "a continuity of highly pleasurable excitement, it is evident enough that this is impossible." Happiness is "moments of [rapture], in an existence made up of few and transitory pains, many and various pleasures, with a decided predominance of the active over the passive, and having as the foundation of the whole not to expect more from life than it is capable of bestowing." 4. Man must do without happiness in order to become noble. That we can do without it cannot be doubted, but we need not do without it and it is not good to do without it unless doing without it increases or tends to increase the sum total of happiness. It is not one's own happiness that counts, but the sum total, and "as between his own happiness and that of others, utilitarianism requires him to be as strictly impartial as a disinterested and benevolent spectator."

5. It is too much to require persons always to act "from the inducement of promoting the general interests of society." But this objection confuses the motives for acting with the criterion for our duties. Utilitarianism tells us that it is our duty to promote the general interests of society, but "no system of ethics requires that the sole motive of all we do shall be a feeling of duty." The motive of an action is irrelevant to determining its moral worth; the motive is relevant to determining only the worth of the person who acts. It is true that "the morality of the action depends entirely upon the intention--that is, upon what the agent wills to do." 6. It renders persons "cold and sympathizing." If this means that utilitarians do not calculate "the qualities of the person who does" an act in judging the rightness or wrongness of an act, that is correct. But all systems of morality are subject to the same complaint, for they all distinguish between judging an act and evaluating a person's character. 7. It is "a godless doctrine." a. But if God desires the happiness of his creatures, "utility is not only not a godless doctrine, but more profoundly religious than any other." b. For those who think we ought to use the will of God as the truest of right and wrong rather than utility, there are two responses: i. Any utilitarian who believes in God's goodness must think him a utilitarian, and ii. Utilitarianism is "a doctrine of ethics, carefully worked out, to interpret to us the will of God." 8. It tells us what is expedient rather than what is moral. No. What is expedient, in the sense in which it is opposed to what is right, is "that which is expedient for the particular interest of the agent himself." But utilitarianism requires that everyone's interests be taken into account and treated equally. 9. It cannot be used because "there is not enough time, previous to action, for calculating and weighing the effects of any line of conduct on the general happiness." Utilitarians distinguish between act and rule utilitarianism and adopt the latter. For "whatever we adopt as the fundamental principles to apply it by; the

impossibility of doing without them, being common to all systems, can afford no argument against any one in particular." That is, we do not "test each individual action directly by the first principle," for that would be impossible. We rather test them by "intermediate generalization[s]." 10. "A utilitarian will be apt to make his own case an exception to moral rules, and, when under temptation, will see a utility in the breach of a rule, greater than he will see in its observance." But no system of ethics can prevent cheating.

Вам также может понравиться

- Community Health Nursing Lecture NotesДокумент8 страницCommunity Health Nursing Lecture NotesStiffany PrietoОценок пока нет

- A Conceptual Framework For Implementation FidelityДокумент9 страницA Conceptual Framework For Implementation FidelityAngellaОценок пока нет

- Institutional SetupДокумент12 страницInstitutional SetupITDP IndiaОценок пока нет

- Lesson 3 NLCДокумент13 страницLesson 3 NLCaileenОценок пока нет

- Field Work 3Документ12 страницField Work 3Cris Angelo PangilinanОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting Language LearnerДокумент13 страницFactors Affecting Language LearnermisterashОценок пока нет

- Arc036-Research Work No.1 (Ekistics)Документ17 страницArc036-Research Work No.1 (Ekistics)Lee BoguesОценок пока нет

- Catholic Faith: A Gift From God That Enables Belief, Hope and LoveДокумент35 страницCatholic Faith: A Gift From God That Enables Belief, Hope and Lovelouie21Оценок пока нет

- Notes On Rousseau Discourse On InequalityДокумент8 страницNotes On Rousseau Discourse On InequalityJessica Karban100% (1)

- Mathematics in ArtДокумент9 страницMathematics in ArtIftikhar Hassan SamoonОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 Plumbing BasicsДокумент8 страницChapter 1 Plumbing BasicsEllen LabradorОценок пока нет

- The Concept of DreadДокумент7 страницThe Concept of DreadO QuinonezОценок пока нет

- PACHEO (Legacy of Rizal To The Youth)Документ9 страницPACHEO (Legacy of Rizal To The Youth)Rizza Manabat PacheoОценок пока нет

- Unit 4: Nursing Process in The Care of Population Groups and CommunityДокумент6 страницUnit 4: Nursing Process in The Care of Population Groups and CommunityFrancis Lawrence AlexanderОценок пока нет

- Education in New Zealand There Are Five Competencies Covered by The National Curriculum. These AreДокумент7 страницEducation in New Zealand There Are Five Competencies Covered by The National Curriculum. These AreShamaica SurigaoОценок пока нет

- St. Augustine On The Problem of EvilДокумент2 страницыSt. Augustine On The Problem of EvilAbhinav AnandОценок пока нет

- Explain Mill's Version of UtilitarianismДокумент3 страницыExplain Mill's Version of UtilitarianismAnna Sophia Darnell BradleyОценок пока нет

- How the First Head Was TakenДокумент6 страницHow the First Head Was TakenVencint Karl TacardonОценок пока нет

- Chapter Project Planning FINALДокумент92 страницыChapter Project Planning FINALtilahunОценок пока нет

- Printed BANGLADESH Minimum Standard EiEДокумент56 страницPrinted BANGLADESH Minimum Standard EiEALI AHAMMEDОценок пока нет

- The Aims of EducationДокумент10 страницThe Aims of EducationPhyllis GrahamОценок пока нет

- TOA 4.1 (Sun Shading) PDFДокумент28 страницTOA 4.1 (Sun Shading) PDFKim NavalОценок пока нет

- Module 4 - RizalДокумент4 страницыModule 4 - RizalAndrea Lyn Salonga CacayОценок пока нет

- Rationalism: Caymo, Eenah Antoinette P. Ii-1 Beced Clima, Jayson Ii-3 BecedДокумент10 страницRationalism: Caymo, Eenah Antoinette P. Ii-1 Beced Clima, Jayson Ii-3 Becedbabyselena_kidah_eenahОценок пока нет

- Lecture 9 - Chi Square Test 2013Документ9 страницLecture 9 - Chi Square Test 2013Carina JLОценок пока нет

- Community Health NursingДокумент36 страницCommunity Health Nursingglen100% (1)

- Development CommunicationДокумент12 страницDevelopment CommunicationMia Sam100% (1)

- A Case StudyДокумент15 страницA Case StudySammah Obaji Ori100% (1)

- 6.6.2 Updated Local Shelter Planning Manual by Housing - Urban Development Coordinating Council and United Nations Resettlement ProgrДокумент12 страниц6.6.2 Updated Local Shelter Planning Manual by Housing - Urban Development Coordinating Council and United Nations Resettlement ProgrPrincess VistalОценок пока нет

- SYNOPSIS: in Order To Create The Cities of The Future, We Need To Systematically DevelopДокумент16 страницSYNOPSIS: in Order To Create The Cities of The Future, We Need To Systematically DevelopMary Jane MolinaОценок пока нет

- Wardha Education SchemeДокумент23 страницыWardha Education SchemeMohd Wasiuulah Khan0% (1)

- Application of exponents in real life: Counting very small and large numbersДокумент15 страницApplication of exponents in real life: Counting very small and large numbersElango PОценок пока нет

- Errors in Measurement of DistanceДокумент3 страницыErrors in Measurement of DistanceB S Praveen BspОценок пока нет

- Thesis Variables and MethodsДокумент5 страницThesis Variables and MethodsPrince JenovaОценок пока нет

- CURRICULUM VITAE OF EDDY BABORДокумент20 страницCURRICULUM VITAE OF EDDY BABORmacel cailingОценок пока нет

- John Locke On The Goal of Education PDFДокумент9 страницJohn Locke On The Goal of Education PDFKendry Jose Briceño TorresОценок пока нет

- Essay On UtilitarianismДокумент2 страницыEssay On UtilitarianismJohnny A-lОценок пока нет

- Definition, Scope, & Importance of Environmental ScienceДокумент18 страницDefinition, Scope, & Importance of Environmental ScienceJohn Edlouie MadlangsakayОценок пока нет

- Anderson - Biblical Theology and Sociological InterpretationДокумент13 страницAnderson - Biblical Theology and Sociological InterpretationCecilia BustamanteОценок пока нет

- Concept of Science EducationДокумент6 страницConcept of Science EducationngvmrvОценок пока нет

- Arena Chapel in Padua, ItalyДокумент9 страницArena Chapel in Padua, ItalyChristian LomasangОценок пока нет

- RRA and PRAДокумент7 страницRRA and PRAYeasin ArafatОценок пока нет

- A Project Report ON Right To Education: ContentsДокумент12 страницA Project Report ON Right To Education: ContentsPrakhar jainОценок пока нет

- Field Work No.2Документ3 страницыField Work No.2Jhon Carlo PadillaОценок пока нет

- EDUCATION: NATURE AND PURPOSESДокумент5 страницEDUCATION: NATURE AND PURPOSESIGNOU ASSIGNMENTОценок пока нет

- InTech-Internationalization and Globalization in Higher EducationДокумент20 страницInTech-Internationalization and Globalization in Higher EducationPedroОценок пока нет

- Sir Ritchel - . .'Документ159 страницSir Ritchel - . .'Aya ChanОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill - Lec 9 HW PhilДокумент5 страницJohn Stuart Mill - Lec 9 HW PhilalyssaОценок пока нет

- MillДокумент4 страницыMillDlorrej OllamОценок пока нет

- Was Mill an Act or Rule Utilitarian? (39 charactersДокумент3 страницыWas Mill an Act or Rule Utilitarian? (39 charactersCastor Edström EngstedtОценок пока нет

- Pretty Orange Dignos Pelayo - BSA2Документ3 страницыPretty Orange Dignos Pelayo - BSA2Orange PelayoОценок пока нет

- Topic 2 - Normative Theories of Ethics (Week 3)Документ19 страницTopic 2 - Normative Theories of Ethics (Week 3)Pei JuanОценок пока нет

- Utilitarianism: Two AttractionsДокумент8 страницUtilitarianism: Two Attractions程海逸Оценок пока нет

- Objections To UtilitarianismДокумент5 страницObjections To UtilitarianismBlue SirenОценок пока нет

- Ethics of UtilitarianismДокумент6 страницEthics of UtilitarianismArly Kurt TorresОценок пока нет

- Distinction Between Bentham and Mill's Version of UtilitarianismДокумент5 страницDistinction Between Bentham and Mill's Version of UtilitarianismSteffОценок пока нет

- Chapter Four Critique of John Stuart Mill'S UtilitarianismДокумент11 страницChapter Four Critique of John Stuart Mill'S UtilitarianismIdoko VincentОценок пока нет

- EPF Passbook Details for Member ID RJRAJ19545850000014181Документ3 страницыEPF Passbook Details for Member ID RJRAJ19545850000014181Parveen SainiОценок пока нет

- LAC-Documentation-Tool Session 2Документ4 страницыLAC-Documentation-Tool Session 2DenMark Tuazon-RañolaОценок пока нет

- 7 Tactical Advantages of Explainer VideosДокумент23 страницы7 Tactical Advantages of Explainer Videos4ktazekahveОценок пока нет

- The Invisible Hero Final TNДокумент8 страницThe Invisible Hero Final TNKatherine ShenОценок пока нет

- Masonry Brickwork 230 MMДокумент1 страницаMasonry Brickwork 230 MMrohanОценок пока нет

- SOP for Troubleshooting LT ACB IssuesДокумент9 страницSOP for Troubleshooting LT ACB IssuesAkhilesh Kumar SinghОценок пока нет

- Aircraft ChecksДокумент10 страницAircraft ChecksAshirbad RathaОценок пока нет

- City of Brescia - Map - WWW - Bresciatourism.itДокумент1 страницаCity of Brescia - Map - WWW - Bresciatourism.itBrescia TourismОценок пока нет

- FINAL - Plastic Small Grants NOFO DocumentДокумент23 страницыFINAL - Plastic Small Grants NOFO DocumentCarlos Del CastilloОценок пока нет

- Models of Health BehaviorДокумент81 страницаModels of Health BehaviorFrench Pastolero-ManaloОценок пока нет

- 99 181471 - Sailor System 6000b 150w Gmdss MFHF - Ec Type Examination Module B - Uk TuvsudДокумент6 страниц99 181471 - Sailor System 6000b 150w Gmdss MFHF - Ec Type Examination Module B - Uk TuvsudPavankumar PuvvalaОценок пока нет

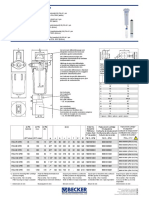

- Medical filter performance specificationsДокумент1 страницаMedical filter performance specificationsPT.Intidaya Dinamika SejatiОценок пока нет

- Riedijk - Architecture As A CraftДокумент223 страницыRiedijk - Architecture As A CraftHannah WesselsОценок пока нет

- Agricultural Sciences P1 Nov 2015 Memo EngДокумент9 страницAgricultural Sciences P1 Nov 2015 Memo EngAbubakr IsmailОценок пока нет

- Compare and Contrast High School and College EssayДокумент6 страницCompare and Contrast High School and College Essayafibkyielxfbab100% (1)

- BMXNRPДокумент60 страницBMXNRPSivaprasad KcОценок пока нет

- Levels of Attainment.Документ6 страницLevels of Attainment.rajeshbarasaraОценок пока нет

- Center of Gravity and Shear Center of Thin-Walled Open-Section Composite BeamsДокумент6 страницCenter of Gravity and Shear Center of Thin-Walled Open-Section Composite Beamsredz00100% (1)

- Youth, Time and Social Movements ExploredДокумент10 страницYouth, Time and Social Movements Exploredviva_bourdieu100% (1)

- Caribbean Examinations Council Caribbean Secondary Certificate of Education Guidelines For On-Site Moderation SciencesДокумент9 страницCaribbean Examinations Council Caribbean Secondary Certificate of Education Guidelines For On-Site Moderation SciencesjokerОценок пока нет

- SuffrageДокумент21 страницаSuffragejecelyn mae BaluroОценок пока нет

- Mechanical Questions & AnswersДокумент161 страницаMechanical Questions & AnswersTobaОценок пока нет

- Nqs PLP E-Newsletter No68Документ5 страницNqs PLP E-Newsletter No68api-243291083Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 - IntroductionДокумент42 страницыChapter 1 - IntroductionShola ayipОценок пока нет

- France: French HistoryДокумент16 страницFrance: French HistoryMyroslava MaksymtsivОценок пока нет

- 2.0 - SITHKOP002 - Plan and Cost Basic Menus Student GuideДокумент92 страницы2.0 - SITHKOP002 - Plan and Cost Basic Menus Student Guidebash qwertОценок пока нет

- Application Programming InterfaceДокумент12 страницApplication Programming InterfacesorinproiecteОценок пока нет

- Choose the Best WordДокумент7 страницChoose the Best WordJohnny JohnnieeОценок пока нет

- 277Документ18 страниц277Rosy Andrea NicolasОценок пока нет

- DMS-2017A Engine Room Simulator Part 1Документ22 страницыDMS-2017A Engine Room Simulator Part 1ammarОценок пока нет