Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Ehg6 3 Richter

Загружено:

deepashajiОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ehg6 3 Richter

Загружено:

deepashajiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

*

Brian Kelleher Richter. Assistant Professor of Business, Economics, and Public Policy, Richard Ivey

School of Business, University of Western Ontario, 1151 Richmond Street North, London, Ontario N6A

3K7, CANADA. brichter@ivey.uwo.ca. office: +1 (519) 661-3267. Mobile (USA): +1 (310) 709-5745.

web: http://alum.mit.edu/www/bkr .

**

The lateset version of this paper is available on SSRN at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1750368

***

This early stage research has already benefit from conversations with and comments from Ray Fisman,

Romain Wacziarg, John deFigueiredo, Bruce Carlin, Dan Treisman, Edward Leamer, J ason Snyder, Guy

Holburn, Adam Fremeth, Oana Branzei, Tima Bansal, and Peter Robertsin addition to audience members

at NYU Sterns 2010 Conference on Social Entrepreneurship and discussion participants engaged in the

Centre for Sustainable Value at the University of Western Ontarios Richard Ivey School of Business. I

thank J effrey Timmons and Krislert Samphantharak for helping to collect and code the lobbying data used

for an earlier project. I am also grateful for the support of the Harold and Pauline Price Center for

Entrepreneurial Studies Research at UCLAs Anderson School.

Good and Evil: The Relationship between

Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Political Activity

Brian Kelleher Richter

*

This draft: 28 January 2011

Abstract

To determine if corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate political activity are

economic substitutes or economic complements, I assemble and analyze the largest

dataset possible from existing data sources incorporating both types of non-market

behavior. Examining the joint distribution of an index of firms CSR behavior and an

indicator of whether or not firms lobby reveals that firms at both the positive and the

negative extremes of social responsibility are more likely to have been politically active.

Regressing the CSR index and a measure of lobbying intensity, individually, on Tobins

Q allows me to test whether CSR and corporate political activity separately enhance

firms value; regressing an interaction between the CSR index and the measure of

lobbying intensity on Tobins Q, allows me to test whether they play complementary

roles in enhancing firms value. Higher CSR ratings, more intensive lobbying, and the

interaction between the CSR rating and lobbying intensity all appear to increase value

when comparing firms; however, when each firm is studied over time, only the

interaction between CSR rating and lobbying intensity appear to increase firm value.

Taken together this suggests that firms CSR positions work as an economic complement

to its political activity rather than a substitutejointly the two types of non-market

behavior increase a firms value, while independently each activity is more difficult to

reconcile and perhaps may simply be symptomatic of some other inherently unobservable

firm-fixed characteristic such as good management. Illustrative cases round-out the

large dataset analysis.

Keywords: Non-Market Strategy, Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Political

Activity, Lobbying, Financial Performance, Substitutes, Complements

1

1 Introduction

Are corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate political activity

substitutes or complements? The simplistic, popular answer to this question is that they

are substitutes, since it is easy to classify firms that engage in CSR as being good and

equally easy to classify firms that attempt to exert political influence as being evil; the

reality, however, is likely to be more complex. Despite the importance of untangling this

relationshipwhich potentially has major implications for our understanding of both

CSR and corporate political activityscarce resources have been devoted to it to date.

Nevertheless, Lyon and Maxwell (2008) have called for exactly this type of research,

suggesting that corporate political activities need to be incorporated into an overarching

framework for CSR.

For consumers, we think of substitutes as being goods where an individual derives

the same value from picking some fixed quantity of one good versus another good (e.g.

wearing a red shirt or wearing a blue shirt gives an individual the same utility) and

complements as goods where consumers derive the most value from consuming both

goods simultaneously in appropriate proportions (e.g. left shoes and right shoes only give

consumers utility when consumed in equal proportions). In the case of CSR and

corporate political activity, we can think of these as distinct non-market actions firms

may pursue to manage their external business environment; however, the relationship

between the two types of non-market strategies is less clear than that between red shirts

and blue shirts or that between left shoes and right shoes. Does CSR create more value

2

for firms when done by itself or when coupled with an appropriate, complementary,

corporate political stance?

We could imagine a manager whose only concern is increasing the value of his

business seeing CSR and lobbying as substitutes and making a choice between one or the

other: e.g. he could choose (i) to run a firm that derives its profits from choosing a

cheaper production process that requires heavy pollution (social irresponsibility) and

lobbying to protect his ability to pollute; or, he could choose (ii) to run a firm that derives

its profits from selling the same good using a more expensive green production

technology and hoping to sell it to consumers who appreciate and are willing to pay a

premium for his efforts to be good, as in Bagnoli and Watts (2003) who argue that

firms compete for socially responsible consumers.

1

Alternatively, we could imagine a

manager who is more strategic in his decision-making and sees CSR and lobbying as

complements: e.g. he could pursue good CSR by developing a (more costly) green

technology and attempt to gain value from being at the top end of the CSR spectrum by

lobbying to push the regulatory environment in a direction that benefits his ownership of

a proprietary socially responsible technology at the expense of his competitors.

2

Which

of these alternative structures for non-market activity creates the most valuable firm?

The purpose of this paper is to determine whether or not CSR and corporate

political activity are substitutes or complements. It achieves this goal by merging well-

known datasets on CSR and firms political activity that to date have only been examined

1

Fisman, Elfenbein, and McManus (2010) find a similar result when they show that consumers are willing

to spend more when goods are linked to charitable giving, at least on eBay.

2

In the real world, we see this with companies like Toyota which own the green Prius hybrid technology

pushing for higher global fuel economy standards that all manufacturers must meet, rather than percentage

increases in average fuel economy of each manufacturer's fleet--the regulatory measure preferred by

manufacturers of less socially responsible cars that emit more pollutants.

3

separatelyand analyzing them jointly. First, it examines the peculiarities of the joint

empirical distribution of firms lobbying behavior and firms CSR; then it tests how CSR

and lobbying behavior, individually and jointly, impact firms valuations. This research

reveals that (i) firms at both negative and positive extremes of a CSR index are more

likely to have lobbied than firms that display more typical levels of socially responsible

behavior, that (ii) both CSR and lobbying, individual and jointly, explain higher financial

valuations when comparing firms; and that (iii) more intensive CSR and lobbying work

as complements when examining individual firms over time since their interaction

continues to explain higher valuations, however, more intensive CSR and lobbying

efforts alone may lead to lower valuations within a single firm over time.

1.1 Literature Review

Past researchers have studied questions related to CSR and financial performance

and corporate political activity and financial performance independently. They have not

considered empirically the possibility that CSR and corporate political activity may be

related and that good managers may choose to engage in both types of non-market

strategies. Consequently, prior literature has not considered the joint effects of corporate

political influence and CSR on firms financial valuations.

The only consensus that has emerged from the separate lines of research

regressing measures of CSR and of corporate political influence on measures of firms

financial performance is that while possible to document the value of either CSR or

lobbying between firms that it is harder to document eithers value within firms, when

controlling for persistent firm-fixed factors. One explanation for why the effects

disappear within firms is that good CSR or engaging in political activity may simply be

4

symptomatic of good management which is an inherently difficult to measure and,

plausibly, firm-fixed characteristic. Moreover, to date no study has looked at data on

both CSR and corporate political activity simultaneously despite some suggestions to

investigate the potential relationship between the two types of non-market behavior

both of which may be the result of good management.

CSR and Financial Performance

Before CSR was at the forefront of popular media attention,

3

the Nobel prize-

winning economist Milton Freidman (1970) famously quipped that the only social

responsibility of business is to increase its profits suggesting that there should be no

link between firms CSR initiatives and their financial performance. Freidman (1970)

went on to suggest that if there is any relationship, CSR initiatives should be a drag on

firm performance as they can only be the result of managerial malfeasance. Griffin and

Mahon (1997) and Margolis, Elfenbein, and Walsh (2009) provide extensive literature

reviews on the academic debate Friedmans comment sparked, chronicling a large

number of studies that come to divergent conclusions about CSRs effect on firms

financial performancesome finding a negative effect, others an inconclusive effect, and

yet others a positive effect. I highlight only a few key studies and their similarities.

Leading business strategy scholars, such as Porter and Kramer (2002), have

suggested that firms can benefit from CSR efforts as existing views of the firm fail to

take into account managing relationships with all stakeholders, which is precisely where

CSR may provide firms a competitive advantage. This Organizational Theory View of

3

A simple search of Google News Trends shows that reporting on the topic of CSR took off in the early

2000s: http://www.google.com/archivesearch?q=corporate+social+responsibility&btnG=Search+Archives

5

CSR tends to focus all stakeholders rather than just shareholders alone; between firm

studies tend to be used to support the view. Waddock and Graves (1997a) run a test

comparing different firms that indicates higher CSR scores predict better financial

performance. In separate research, Waddock and Graves (1997b) suggest that one reason

they may find the earlier positive relationship between CSR and financial performance

may be that firms with higher quality management perform better at CSR. Hillman and

Keim (2001) find support for the higher quality management argument when they show

that managers who pay attention to all stakeholders on social fronts are rewarded by

shareholders when comparing firms. Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynes (2003) conduct a

meta-analysis of studies comparing firms, concluding that in aggregate better CSR has a

positive effect of firms financial performance.

In critical re-evaluations of the work showing positive effects of CSR on firms

financial performance between firms, several more recent studies find that the positive

effects disappear in tests examining single firms over time (within firm tests), producing

results more consistent with Friedmans (1970) early predictions and the Economic

View of CSR. In particular, Moon (2007) finds that most prior research really just

captured unobserved heterogeneity specific to firms and that once these are controlled

for, CSR actually has a negative short-run effect on firms valuations. In a similar vein,

Baron (2009) constructs a theory which suggests that in equilibrium there should be no

within firm effects to being stronger along observable dimensions of corporate social

performance since firms choose to engage in such behavior only when pressured to do so

by non-market stakeholders in their business environment. Baron, Harajoto, and J o

6

(2009) conduct a three-stage least-squares empirical test that largely supports Barons

(2009) theory.

Corporate Political Activity and Financial Performance

Moving to the literature on corporate political activitys effect on firms aggregate

financial performance, the debate follows a similar pattern: it typically finds a positive

effect between firms, but a negative or inconclusive effect within firms or when otherwise

controlling for managerial qualities. In a recent study, Chen, Parsley, and Yang (2010)

show that portfolios composed of firms that lobby more intensely outperformed

portfolios of those that lobby less intensely; they caution, however, that simply spending

the most on lobbying does not necessarily lead to better financial performance as their

test is one that compares different firms, rather than examining single firms over time.

Agrawal and Knoeber (1999) find negative relationships between the intensity of various

measures firms corporate political activity and their financial performance as measured

by Tobins Q in the US context when controlling for fixed characteristics of the

management and governance of firms. The Agrawal and Knoeber (1999) result appears

to hold in other contexts as well: Claessens, Feijen, and Laeven (2008) find that firms

who make larger campaign contributions in Brazil have a lower Tobins Q, controlling

for firm fixed factors; and, Wei, Xie, and Zhang (2005) find that more politically

influential firms in China also have a lower Tobins Q.

2 Assembling a Dataset on CSR and Corporate Political Activity

To achieve this papers purpose, I assemble the most comprehensive dataset

possible based on available CSR and lobbying data. This allows me to begin answering

7

whether the two types of non-market strategies are substitutes or complements. My

dataset is an unbalanced panel covering US firms for the years 1998 through 2005 and

contains at most 3,350 firms in the cross-section. To construct it, I merged together data

that appears in (i) the most complete database available on CSR, (ii) public records on

firms lobbying expenditures, and (iii) firms accounting statements.

2.1 CSR Data from KLD

The CSR data comes from Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini Research & Analytics

(KLD) and their KLD STATs dataset. This is the most comprehensive and consequently

the most widely used CSR dataset for academic research.

4

The sample of firms with

KLD data available is what limits the cross-section of firms in my sample; KLD scores

are available primarily for the largest firms by market capitalization.

5

KLD codes directly observable CSR attributes in 7 issue areascorporate

governance, community engagement, diversity, employee relations, environment,

humanitarian efforts, and product qualitiesas either CSR strength or concern dummy

variables. More details on what the attributes are within these issue areas and how the

data are coded is available in the appendix. As in prior academic research using the KLD

data, I sum all strength indicators and subtract all the concern indicators to create a KLD

Index variable.

6

Higher and positive KLD Index scores indicate stronger aggregate CSR

4

For example, the KLD data is used by, among others: Waddock and Graves (1997); Hillman and Keim

(2001); Moon (2007); and, Baron, Harajoto, and J o (2009).

5

In addition to using market capitalization as a screen for which firms to include in its sample, KLD also

includes some additional firms based on a priori expectations that they are good at CSR; however, these

firms are easily identifiable as being part of the Domini 400 Social Index firms and hence excludable in

robustness checks. My primary results hold even when excluding Domini 400 firms that would not

otherwise be in my sample; more on this follows in a robustness section.

6

Unfortunately there is no theory to guide any other kind of aggregation of the data. (Hillman and Keim,

2001) The problem with this method of index construction is that it implicitly gives equal weight to each

8

records; lower and negative KLD Index scores indicate aggregate social irresponsibility.

A histogram of the KLD Index indicates that firms CSR levels tend to follow a normal

distribution with a mean near zero. Summary statistics follow in Table 1.

Chatterji, Levine, and Toffel (2009) examined the underlying integrity of the

KLD Data. They find that while it is a reasonable proxy for some types of CSR activity,

it is a noisy measure that both understates and overstates firms CSR levels.

7

2.2 Lobbying from Public Records

The lobbying data I use comes from legally required public disclosures of firms

lobbying expenditures.

8

It comes from Richter, Timmons, and Samphantharak (2009)

who coded the Center for Responsive Politics cleaned public records data such that it

can be merged into other datasets containing additional information on firms, like

COMPUSTAT for financial accounting data. The lobbying data reliably covers the

years 1998 through 2005, which limits the time-dimension of my dataset. It is the best

measure of firms corporate political activity available as firms spend an order of

magnitude more on lobbying than on (highly correlated) campaign contributions.

9

(Milyo, Primo & Groseclose, 2000; Ansolabehere, Snyder, & Tripathi, 2002)

From this dataset, I will use two primary variables based on lobbying disclosures

for my analysis. The first of these is a dummy variable that takes on a value of 1 if firms

KLD issue, when in reality there is no reason to believe that being a heavy polluter (a KLD concern) should

be equally offset by having a minority CEO (a KLD strength).

7

Consequently, Chatterji, Levine, and Toffel (2009) advocate using more detailed data when it is available

on specific issues like firms pollution level from public records; however, they provide little guidance on

what may be a better measure across all CSR issues.

8

Firms have been legally required to report all lobbying expenditures in the US since the Lobbying

Disclosure Act of 1995.

9

Furthermore, existing research has documented that campaign contributions have little impact on the

legislative process and may merely be a form of corporate consumption. (Ansolabehere, de Figueiredo,

and Snyder , 2003)

9

lobby and a value of 0 otherwise. Summary statistics included in Table 1 reveal that only

about 28% of the firms in the sample actually engage in any sort of formal lobbying.

10

For this study, I have also created a measure of firms lobbying intensity that is the

percentage of a firms total (accounting) assets spent on lobbying. The advantage of this

variable is that it is defined in a manner that makes it independent of scale (i.e. is

comparable across firms regardless of their size), which also makes it appropriate to

include in Tobins Q valuation regressions.

2.3 Tobins Q (Dependent Variable) and Controls from COMPUSTAT

I will use Tobins Q as the dependent variable in a regression-based test of

whether corporate political activity and CSR work as substitutes or complements, as

Tobins Q is the most-widely used measure in studies of both CSRs effect (on financial

10

28% of the firms in the sample lobbying is a high percentage when compared to the fraction of all active

firms in the COMPUSTAT database which lobby (around 10%). The reason that more firms in the sample

I use for this research lobby is that firm size is a good predictor of whether or not firms lobbyand the

sample included here is limited to those firms which KLD rates on CSR dimensions, a sample that includes

primarily the largest firms in the US.

TABLE 1 - Summary Statistics for Key Variables

Mean Median Std. Dev Min Max

KLD Index -0.19 0.00 2.12 -11.00 11.00

KLD Strengths 1.43 1.00 1.98 0.00 18.00

KLD Concerns 1.61 1.00 1.84 0.00 16.00

Mean Median Std. Dev Min Max

If Lobby (Dummy) 0.28 0.00 0.45 0.00 1.00

Lobbying Intesity 0.0043 0.00 0.0224 0.00 0.99

Lobbying Variables

CSR Variables

10

performance) and corporate political activitys effect (on financial performance).

11

I

construct the Tobins Q variable from COMPUSTAT, such that it equals the market

value of the firm divided by the book value of the firm. When the variable takes on

values greater than one, the market perceives the combination of tangible and intangible

resources the firm has assembled as being worth more than the replacement value of the

firm; hence, higher values of Tobins Q indicate superior financial performance of the

firm. Furthermore, a managers goal should be to maximize his Tobins Q value as this

indicates that he is using the firms resources in the best possible manner.

Studies using Tobins Q as the dependent variable typically include a set of

control variables related to other observable characteristics of the firm that are included

on their financial statements. I take data on the most commonly incorporated control

variableslog(total assets), leverage, capital intensity, R&D intensity

12

, and

log(employees)from COMPUSTAT.

13

3 The Joint Distribution of CSR and Lobbying

As a first step in my empirical attempts to discern whether social responsibility

and lobbying are substitutes or complements, I examine the joint empirical distributions

of the attributes. This goes beyond the summary statistics of the independent

distributions of firms lobbying activity and CSR levels provided in Table 1.

11

For example, in the CSR literature Tobins Q is used by Moon (2007) and Baron, Harajoto, and J o (2009)

among others, and in the corporate political activity literature it is used by Agrawal and Knoeber (1999),

Claessens, Feijen, and Laeven (2008), and Wei, Xie and Zhang (2005) among others.

12

R&D intensity is particular important to include according to a study by McWilliams and Siegl (2000),

who claim models that do not include it are misspecified.

13

Leverage is defined as Total Debt divided by Total Assets; Capital Intensity is defined as Property, Plant

and Equipment (Net) divided by Total Assets; and, R&D Intensity is defined as research and development

expenditures divided by Total Assets, using a value of 0 where research and development expenditures has

an N/A observation in COMPUSTAT.

11

If corporate political activity and CSR were substitutes, then we would expect to

find that only the most socially irresponsible firms are likely to lobby, since these firms

have chosen to ignore CSR activity in favor of engaging with political actors. If

corporate political activity and CSR were complements, then we would expect firms

lobbying behavior to vary in some other systematic way with their CSR behavior and

perhaps firms having the best CSR records would be more likely to engage in corporate

political activity. Of course, it is also possible that there is no relationship between

corporate political activity and CSR, in which case the distribution of CSR activity

should look identical for firms regardless of their lobbying (political activity) status.

3.1 Firms that Lobby have a KLD Index Distribution with Fatter Tails

Figure 2 shows overlaid histograms of the density of KLD scores (i) for firms that

lobby and (ii) for those firms that do not lobby.

14

The first moment, or mean, of both

distributions appears the same, but the second moment, or variance, appears to differ.

The graph shows that firms at both extremes of social responsibility are more likely to

lobby than firms with more typical levels of CSR: the most socially irresponsible and the

most socially responsible firms are the ones that lobby. While the finding that the most

socially irresponsible firms lobby could by itself suggest a substitute-like relationship, the

parallel finding that the most socially responsible firms also lobby is more suggestive of a

complementary relationship.

14

Figure A1 in the Appendix shows the Kernel Density functions of the KLD index by lobbying status.

12

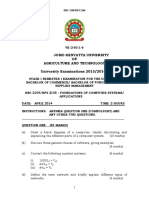

Figure 1 Histograms of KLD Scores, by Lobbying Status

To test whether the two distributions shown in Figure 1 are different more

formally, I examine their discrete joint empirical distributions in Table 2. A Chi-squared

test indicates a very high likelihood that firms that lobby have a different KLD index

distribution with fatter tails than firms that do not lobby, as the p-value is less than 0.000.

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

-11-10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

D

e

n

s

i

t

y

Sum of KLD Strengths/Concerns

Histograms of KLD Scores, by Lobbying Status

Firms that DO NOT Lobby

Firms that DO Lobby

TABLE 2 - Empirical Distribution Tests

KLD Strengths minus Weaknesses

C

o

u

n

t

s -11 -10 -9 -8 -7 -6 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Tot.

0 1 1 1 0 5 19 40 113 290 855 1762 2301 1224 487 253 125 43 24 11 2 0 3 0 7560

1 1 2 7 19 34 52 78 153 200 328 500 495 352 262 172 98 60 41 30 15 11 3 4 2917

T

o

t

.

2 3 8 19 39 71 118 266 490 1183 2262 2796 1576 749 425 223 103 65 41 17 11 6 4 10477

Value p-value

KLD Strengths minus Weaknesses

L

o

b

b

y

i

n

g

D

u

m

m

y

C

o

u

n

t

s

Test Statistics

This table presents the empirical joint distribution counts of the number of firms that fall into certain

KLD Score and Lobbying categories in the full dataset used in the paper. It also runs tests on the

categorical densities to show that the distribution for firms that lobbying versus those that do not are

statistically distinguishable.

937.127 0.000 Pearson Chi-Squared

13

Taken together it is clear that the CSR behavior of firms that lobby is different

than that of firms that do not lobby. Given that the distribution for firms that do lobby is

fatter at both positive and negative tails, we can preliminarily deduce that lobbying and

social responsibility are complements, since their distributions vary together in a

systematic way.

3.2 KLD Index vs. Lobbying Intensity

Another way to examine the joint empirical distribution of CSR and corporate

political activity is to look at a scatterplot of KLD Index scores versus the measure of

lobbying intensity. This appears in Figure 2. It shows that despite firms at the extremes

of social responsibility being more likely to lobby (as shown in Figure 1), firms at the

extremes of social responsibility are less likely to lobby as intensively as firms in the

middle of the social responsibility distribution.

Figure 2 Scatterplot of Lobbying Intensity vs. KLD Score

Another way to think about the relationship between substitutes and complements

.00

.05

.10

.15

.20

.25

.30

-12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12

Total Number of KLD Strengths minus Concerns

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

a

g

e

o

f

A

s

s

e

t

s

S

p

e

n

t

o

n

L

o

b

b

y

i

n

g

Scatterplot of Lobbying Expenditure (% of Assets) by KLD Score

14

is to think about what the shape of their indifference curves (or isoquants) should look

like. If two goods are substitutes, their indifference curve should be straight lines at an

oblique angle with respect to the origin (as the two inputs should have a constant

marginal rate of substitution); if two goods are complements their indifference curves

should be convex with respect to the origin (as their marginal rate of substitution should

vary with the levels of the two inputs).

15

Plotting firms lobbying intensity versus their

KLD index (which are the axes on an indifference curve/isoquant graph) in Figure 2

shows that at the upper bounds firms use of CSR and lobbying are convex towards the

origin, suggesting that they may be complementary inputs managers can use together to

increase the value of their firms. The problem with treating this graph as if it were an

indifference curve/isoquant graph, however, is that the utility/output of each firm is not

held at constant levels across all observations as they should be in a formal test. We can

include controls to hold other factors influencing firms valuations constant and

approximate the marginal rate of substitution between CSR and corporate political

activity in a regression based test I run in the next section.

4 A Test Linking CSR and Lobbying to Financial Performance

As alluded to above, one simple way to test if any two economic variables are

substitutes or complements involves calculating their marginal rate of substitution. This

test works because whenever two economic variables are substitutes their marginal rate

of substitution is constant and whenever they are complements their marginal rate of

substitution is a function of the underlying variables.

15

See Appendix Figure A2 for the case of Substitutes and Figure A3 for the case of Complements.

15

Using this logic, we can test whether CSR and corporate political activity are

substitutes or complements if we can estimate how they enter into a firms valuation

since this is a firms equivalent to a utility function which we would need to differentiate

with respect to our variables of interest to calculate their marginal rate of substitution.

We can do this since we have data on firms valuations, as measured by Tobins Q, and

believe that their valuations are a function of CSR and corporate political activity among

other factors. A firms financial valuation as a function of non-market activity variables

can be estimated by running regressions of the form:

Iobin

i

s = CSR

t

+z Iobby

t

+ n CSR

t

Iobby

t

+ y X

t

+ o + e

where CSR

t

represents the KLD Index variable; Iobby

t

represents the Lobbying

Intensity variable; X

t

represents other control variables common in regressions on

Tobins Q; and, the constant/fixed-effects variable o varies depending upon whether we

want the test to be between or within firms.

16

We can then take the coefficient estimates from the above regression and use

these to approximate the marginal rate of substitution between CSR and corporate

political activity, which allows us to determine whether or not CSR and corporate

political activity are substitutes or complements. If the marginal rate of substitution

between CSR and political activity is a constant then the two inputs to a firms valuation

are substitutes. If the marginal rate of substitution between CSR and political activity is a

function of those inputs to a firms valuation then the two variables are complements.

16

This regression is appropriate if we believe that CSR and lobbying efforts are not functions of financial

markets contemporaneous valuation of a firm.; otherwise there would be a potentially endogeneity issue.

This seems reasonable unless we believe that managers change their current CSR behavior and lobby

efforts in response to the firms current financial market valuations rather than because of a longer term

(potentially strategic) commitment to socially responsibility or strategic political activity.

16

From the regression above, we calculate a firms marginal rate of substitution as:

HRS

CSR,Lobbng

=

o|Iobin

i

s ]

oCSR

o|Iobin

i

s ]

oIobby

=

+ nIobby

z +nCSR

Hence, if we estimate the coefficient on the interaction between CSR and corporate

political activity (n) to be zero, HRS

CSR,Lobbng

will be a constant indicating that CSR

and corporate political activity are substitute inputs for managers. Alternatively, if we

estimate that the coefficient on the interaction between CSR and corporate political

activity (n) has a non-zero value, then HRS

CSR,Lobbng

will be a function of CSR and

corporate political activity, indicating that the two types of non-market strategies are

complements.

4.1 Estimates Between Firms Show Value of Both CSR and Lobbying

and Suggest a Complementary Relationship

As a first test of whether CSR and lobbying are complements or substitutes using

Tobins Q regressions and the framework outlined above, I estimate between regressions

that include period, but not firm fixed-effects. I estimate the regressions that compare

different firms first to be consistent with the Organizational Theory View of CSR and

the lobbying literatures that finds a positive effect of CSR and lobbying independently on

firms financial valuations when comparing different firms. In the next sub-section, I

will run regressions that look within individual firms over time and that may provide a

more econometrically sound test, as they control for unobserved firm-specific

heterogeneity such as managerial quality which may be influencing decisions related to

the levels of firms CSR efforts and the intensity of their political activity.

17

Hence, as a first test, I estimate variations on the between regression:

Iobin

i

s = CSR

t

+ z Iobby

t

+n CSR

t

Iobby

t

+ y X

t

+o

t

+ e

We should expect to find a positive and significant coefficient () on the level of CSR

and a positive and significant coefficient (z) on the level of lobbying if each

independently increases the valuation of firmswhich would be consistent with prior

research that finds that CSR and lobbying increase firms Tobins Q values when

comparing firms. As outlined in the regression framework section above, we should

expect to find a positive and significant coefficient (n) on the interaction between the

level of CSR and lobbying if the two activities are complements between firms and we

should expect to find a statistically insignificant coefficient (n) on the interaction term if

the two non-market activities are substitutes between firms. The results from my

estimates appear in Table 3.

The results in Table 3 show positive and significant values on the coefficients for

CSR (), corporate political activity (z), and for the interaction between the two types of

non-market behavior (n). The results for CSR () and for corporate political activity (z)

are consistent with the Organizational Theory View of CSR and with past researchers

results showing a positive effect corporate political activity on firms financial

performance when comparing firms. The result for the interaction coefficient (n),

however, is what we are most interested in, since the purpose of running these regressions

was to get at whether or not CSR and corporate political activity are substitutes or

complements; its positive and significant value suggests once again that CSR and

corporate political activity are complements.

18

Despite the results, these between firm regressions are subject to the critique

about unobserved firm-level heterogeneity that proponents of the within firm regressions

offer. The critique suggests that I might find the above results because of unobservable

managerial quality such that better managers choose higher CSR levels and higher

political activity levels, whereas worse managers do not pursue the non-market strategies.

Hence, if I included firm fixed-effects to control for persistent attributes of managerial

quality that might be causing the levels of CSR and lobbying intensity that I am

observing, my positive results could disappear, as higher managerial quality would also

cause higher levels of Tobins Q for other reasons.

TABLE 3 - Between Estimates of Influence of CSR and Lobbying on Valuation

Dependent Variable:

KLD Score 0.054*** 0.055*** 0.035***

(0.008) (0.008) (0.008)

Lobbying (% of Assets) 4.424*** 4.574*** 6.927***

(0.716) (0.715) (0.776)

KLD * Lobbying (% of Assets) 3.874***

(0.505)

log(Assets) -0.290*** -0.286*** -0.287*** -0.287***

(0.014) (0.014) (0.014) (0.014)

Leverage -0.223** -0.278*** -0.223** -0.225**

(0.091) (0.091) (0.091) (0.091)

Capital Intensity -0.274*** -0.330*** -0.268*** -0.286***

(0.079) (0.079) (0.079) (0.079)

R&D Intensity 7.684*** 7.587*** 7.592*** 7.457***

(0.236) (0.237) (0.236) (0.236)

log(Employees) 0.123*** 0.117*** 0.120*** 0.118***

(0.013) (0.013) (0.013) (0.013)

Firm Fixed Effects No No No No

Period Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes

Number of Obs. 9869 9869 9869 9869

R Squared 0.201 0.200 0.204 0.209

Tobins Q

19

4.2 Estimates Within Firms Reveal that the Complementary Relationship

between CSR and Lobbying is Robust

If in within firm tests I still find a positive and significant interaction effect (n)

between CSR and lobbying and if managerial decisions are persistent, then my primary

result that CSR and corporate political activity are complementary is robust.

Here I run such a test, estimating variations on the within regression:

Iobin

i

s = CSR

t

+ z Iobby

t

+ n CSR

t

Iobby

t

+ y X

t

+ o

+ o

t

+ e

The primary difference between the within firms estimates presented here and the

between firms estimates presented in the prior table are that the within firms estimates

control for time-persistent unobservable characteristics by including firm dummy-

variables (o

) in the estimation. Essentially adding the firm dummy-variables (o

) to the

estimation should control for unobservable managerial talent that may be causing firms to

engage in CSR or corporate political activity. This is a test that looks at what happens

inside individual firms over time rather than when comparing different firms as the

regressions did in the last sub-section.

We should expect to find a negative and/or insignificant coefficient () on the

level of CSR and a negative and/or significant coefficient (z) on the level of lobbying if

each independently is a drag on firms valuations or has no measurable effectwhich

would be consistent with prior researchers within firm studies that suggest unobserved

managerial quality drives between firm studies results. As mentioned above, we should

expect to find a positive and significant coefficient (n) on the interaction between the

level of CSR and lobbying if the two activities are complements when examining a single

firm over time if unobserved managerial quality did not drive the between firm result for

20

this coefficient. Otherwise a statistically insignificant coefficient (n) on the interaction

term would indicate that inside an individual firm over time the two non-market activities

may be substitutes. The results from my estimates appear in Table 4.

Consistent with prior researchers within firm tests and the Economic View of

CSR, the results in Table 4 show negative and/or insignificant values on the coefficients

for CSR () and for corporate political activity (z)suggesting that firms superior social

performance and the intensity of firms political activity may in fact be symptomatic of

higher quality management, or some other persistent firm-fixed characteristic, and have

no real direct effect on their financial performance. Nevertheless, the results in Column 4

of Table 4 find a positive and significant coefficient on the interaction between firms

TABLE 4 - Within Estimates of Influence of CSR and Lobbying on Valuation

Dependent Variable:

KLD Score -0.013 -0.013 -0.030***

(0.011) (0.011) (0.011)

Lobbying (% of Assets) -2.572** -2.549** -0.300

(1.127) (1.127) (1.192)

KLD * Lobbying (% of Assets) 3.354**

(0.589)

log(Assets) -1.119*** -1.125*** -1.126*** -1.107***

(0.074) (0.074) (0.074) (0.074)

Leverage 0.169 0.166 0.164 0.163

(0.158) (0.158) (0.158) (0.158)

Capital Intensity -2.069*** -2.066*** -2.066*** -2.041***

(0.323) (0.323) (0.323) (0.322)

R&D Intensity 3.734*** 3.796*** 3.779*** 3.701***

(0.535) (0.535) (0.535) (0.534)

log(Employees) 0.217*** 0.217*** 0.217*** 0.222***

(0.075) (0.075) (0.075) (0.075)

Firm Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes

Period Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes

Number of Obs. 9869 9869 9869 9869

R Squared 0.776 0.776 0.776 0.777

Tobins Q

21

CSR level and lobbying (n)which yet again suggests that CSR and corporate political

activity are complements. Moreover, it suggests that even when controlling for

unobservable managerial quality, CSR may indeed improve firms financial performance,

but only if it is coupled with the appropriate corporate political activityallowing the

firm to overcome the extra costs that CSR efforts alone impose (as suggested by the

negative coefficient ).

If we took the results in Column 4 of Table 4 and held the left hand side

(valuation level) variable constant, and used the point estimates for the coefficients on

CSR (), corporate political activity (z), and their interaction (n) to draw a graph, with

axes representing lobbying intensity and the KLD index, they would generate

indifference curves that are convex with respect to the origin; this result would be

consistent (i) with the shape of the scatter plot of the data in Figure 2, (ii) with the

marginal rate of substitution varying depending upon the level of CSR or the intensity of

corporate political activity, and most importantly (iii) with the notion that CSR and

corporate political activity are complementary inputs for firms that when used together

can raise their valuations despite the negative independent effects of CSR and corporate

political activity.

The result that CSR alone may decrease firms valuations is consistent with the

oft-quoted Milton Friedman (1970) statement that the only social responsibility of

business is to increase its profits. The result that CSR can become profitable when

taking into account firms lobbying behavior, however, may also be consistent with

Friedmans (1970) argument, given that one of the conditions he put on making as much

money as possible was while conforming to the basic rules of society (those embodied

22

in law). To the extent that firms can lobby successfully to alter laws to yield higher

profits by institutionally requiring others to match their socially responsible behavior or

to lose out on business opportunities, Freidman would not have been surprised by my

results. Nevertheless, my results call into question the notion that firms who benefit from

CSR are really doing well by doing good as many proponents of the Organizational

Theory View of CSR suggestor if the firms that benefit the most from CSR are only

doing well by coupling their good with a dose of evil in the form of corporate

political activity.

One reason we may find the result that CSR and corporate political activity are

complements could be that the way firms profit is from the use of social activity as a

competitive weapon potentially giving them a leg up in their lobbying efforts (Devinney

2009). If so this may be a classic case of when regulation is acquired by industry and is

designed and operated primarily for its benefit, otherwise known as regulatory capture.

(Stigler 1971) Traditionally, regulatory capture has been viewed as something that can

be very costly to society given its distributional consequences (Dal B, 2006); however,

if certain firms that are exceptional at some aspect of CSR are more able to capture

regulators and more able to demand regulation that will be good for society, such as

reducing aggregate pollution, the normative consequences are less clear.

4.3 Robustness Checks

I address several possible concerns about robustness of the prior results in this

sub-section. The key points from Table 3 and Table 4 continue to hold after these

robustness tests: when comparing firms better CSR, more intensive lobbying, and the

interaction between better CSR and more intensive lobbying explain higher Tobins Q

23

values; however, when examining individual firms over time only the interaction between

better CSR and more intensive lobbying can explain higher financial valuations and, if

anything, better CSR by itself may reduce firms financial valuations. Taken together my

results remain highly indicative of a complementary relationship between CSR and

corporate political activity.

Checking for Sampling Issues

There are several potential sampling issues that could be driving my primary

results. To overcome sampling-related concerns, I test to see if my results hold up when

the sample is altered to correct for irregularities; they do when I re-run regressions on

different sub-samples of the dataset designed to test their robustness. The sampling

issues include: potential over-representation of socially responsible firms, outliers along

the lobbying intensity dimension, and outliers at the extremes of CSR where there are

only a few observations.

One well known issue related to the cross-section of firms on which KLD collects

CSR data is that the sample likely over-represents firms that are CSR leaders, as a

fraction of the firms included in the dataset, labeled as Domini 400 Social Index firms,

were selected because they were believed a priori to be among the most socially

responsible firms in the US. The rest of the firms were chosen to be in the sample based

on having large market capitalizations. As such I create a subsample of the firms that

excludes the Domini 400 Social Index firms that would not have been included in the

pool of firms if it were not for their large market capitalizations. When I re-run my

regressions in Tables 3 and 4 above, on a sub-sample excluding Domini 400 firms that

would not be in the sample otherwise, the results remain substantively the same.

24

Another sampling concern I tested was sensitivity to outliers. I re-ran the

regressions in Table 3 and Table 4, excluding the extreme outliers on both lobbying and

CSR dimensions from the sample. When I exclude both lobbying and CSR extreme

outliers, my primary result that lobbying and CSR are complements holds up; this

remains true whether excluding just CSR outliers, just lobbying outliers, or both.

17

The

one difference I find occurs when I exclude the most extreme outliers on the lobbying

dimension: I find that in the firm fixed effects (or within) regressions, that the negative

lobbying intensity coefficient becomes statistically insignificant. This suggests that a

firms lobbying intensity alone has no effect on a firms Tobins Q; interactions between

lobbying intensity and CSR levels nevertheless remain important because of their

complementary relationship.

Disaggregating KLD Strengths/Weaknesses

As another test of the robustness of the results, instead of using the total KLD

score as a measure of CSR, I disaggregate the measure into its positive (strengths) and

negative (concerns) components. Otherwise, the regressions are run as within regressions

as in Table 4. The results appear in Table 5.

Table 5 shows that unlike in the Table 4 results, having negative CSR or being

socially irresponsible (measured by KLD concerns rather than firms placement on an

aggregate index) does not increases firms valuations as suggested when the entire KLD

Index is used. Rather, the results in Table 5 suggest that the optimal point for most firms

17

For robustness I tried defining outliers in various ways; however, the simplest way, which was to use a

visual test of the distributions of the data. This led me to exclude firms with a lobbying intensity measure

greater than 0.3 as outliers along the lobbying dimension. It also led me to exclude firms with KLD Index

scores greater than 8 in absolute value as outliers along the CSR dimension.

25

to maximize their valuations, if lobbying intensity is held at its median value of zero, is

for firms to set their CSR level near their median value of zero as well.

We also learn from Table 5 that KLD concerns do not positively complement

firms lobbying efforts like KLD strengths do. Perhaps this is because the firms with

KLD concerns are lobbying for different reasonspotentially to cover up their

irresponsible actions rather than to institutionalize the competitive advantage their CSR

efforts may be giving them.

TABLE 5 - Within Estimates, Role of Good/Bad CSR and Lobbying on Valuation

Dependent Variable:

KLD Strengths -0.073*** -0.072*** -0.098***

(0.015) (0.015) (0.015)

KLD Concerns -0.040*** -0.040*** -0.027*

(0.014) (0.014) (0.014)

Lobbying (% of Assets) -2.572** -2.579** -2.501*

(1.127) (1.124) (1.387)

KLD Strengths * Lobbying (%) 5.057***

(0.817)

KLD Concerns * Lobbying (%) -2.432***

(0.660)

log(Assets) -1.102*** -1.125*** -1.108*** -1.076***

(0.074) (0.074) (0.074) (0.074)

Leverage 0.184 0.166 0.179 0.183

(0.158) (0.158) (0.158) (0.157)

Capital Intensity -2.061*** -2.066*** -2.059*** -2.045***

(0.322) (0.323) (0.332) (0.321)

R&D Intensity 3.775*** 3.796*** 3.821*** 3.737***

(0.533) (0.535) (0.534) (0.532)

log(Employees) 0.211*** 0.217*** 0.211*** 0.214***

(0.075) (0.075) (0.075) (0.075)

Firm Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes

Period Fixed Effects Yes Yes Yes Yes

Number of Obs. 9869 9869 9869 9869

R Squared 0.777 0.776 0.777 0.778

Tobins Q

26

5 Discussion: Illustrative Cases

While there are advantages to analyzing large datasets, over a purely qualitative

analysis focused on specific cases, there are also some shortcomings. Large dataset

analysis alone can obscure the story of what firms are actually doing on the ground; so

far, in this study, it is unclear how firms use their social responsibility positions (positive

or negative) as complements to their lobbying efforts. Given that there are multiple

dimensions of social responsibility/ irresponsibility and multiple issues on which firms

could lobby for policy change or for maintaining the policy status quounderstanding

how managers combine various non-market positions is particularly important.

In this section of the paper, I take the extra step to examine individual cases at the

extremes of the CSR and lobbying distributionshoping to see exactly how firms use

their social responsibility position as a strategic complement to their lobbying behavior.

At the negative extreme, Yum! Brands provides an example of how one firm

complements its relative social irresponsibility with its lobbying efforts by seeking to

maintain the policy/regulatory status quo. At the positive extreme, Hewlett-Packard

provides an example of a firm that leverages its relatively positive social responsibility

position in its lobbying efforts to push for policy changes that would allow them to

monetize their existing activities and raise their rivals costs.

5.1 Yum! Brands Complements Social Irresponsible Positions

with Lobbying Efforts aimed at Maintaining the Status Quo

Yum! Brands, which owns Taco Bell and KFC among other fast-food brands,

falls into the bottom 5% of firms on the social responsibility index most years in the

sample. According to KLD, Yum! Brands has particular weaknesses in: paying

27

executives and directors at unusually high rates; running into controversies related to

affirmative action; finding themselves at the center of other diversity disputes; being

relatively bad at controlling emissions of toxic chemicals; providing employees with poor

benefits packages; running into other disputes with employees about minimum wage pay

and failure to pay overtime; issues with practices in its supply chain; and, finally

concerns over the safety/quality of its products.

Yum! Brands appears to have lobbied in these areas of weakness in their social

responsibility position. Most of their legally-required lobbying disclosure reports show

that Yum! Brands focused on these weaknesses with respect to social issues, such as: on

the minimum wage, on animal rights issues of suppliers, and on environmental emissions.

Yum! Brands lobbying disclosure, however, leaves information about specific bills and

specific positions absent. The only hint of their actual public policy positions, rather than

simply the issues they lobby on, comes from their annual reports and congressional

testimony their officers make. Yum! Brands annual reports cite changes in the minimum

wage as a substantial risk to the company. Testimony by J onathan Blum, the head public

affairs officer at Yum! Brands, to the Senate J udiciary Committee in May 2004 indicates

that Yum! Brands is concerned about the business implications if Yum! Brands had to

source inputs from ethical suppliers who only use what PETA (People for the Ethical

Treatment of Animals) calls more humane ways to process live animals into food

products that if implemented, would cost our company [Yum!] over $50 Million.

In summary, Yum! Brands appears to have complemented its positions of relative

social irresponsibility with a lobbying strategy aimed at preserving the policy status

quowhere preserving the policy status quo would enable Yum! Brands keep input costs

28

down at the peril of various market and non-market stakeholders. By focusing on

maintaining the policy status quo in areas related to their operations, Yum! Brands

appears to have formulated a non-market strategy dependent on their ability to wring

value out of a market position that requires them to operate at the margins of government

regulation vis--vis social issues, making their business particularly sensitive to

tightening operations around social issues.

5.2 Hewlett-Packard Complements Socially Responsible Positions with

Lobbying Efforts advocating for Policy Change towards Firms Strengths

Hewlett-Packard, which is a multinational information technology services,

software, and hardware company, falls consistently into the top 5% of firms on the social

responsibility index. According to KLD, Hewlett-Packard has particular strengths in:

transparent reporting; charitable giving programs (within and outside of the US); having

employee volunteer programs; having internal programs that support diversity and

work/life balance; using clean energy among other environmentally proactive activities;

and, bringing innovative products to market that are good for consumers.

Consistent with the strengths in their social responsibility position, Hewlett-

Packard appears to have lobbied in the same areas: on improving environmental

standards/transparency; on electronics recycling; on government support for decreasing

the digital divide/ economic development; and on patent/trademark issues. Hewlett-

Packards congressional testimony, takes a decidedly different tone than that by Yum!

Brands; rather, than complaining about difficulties and costs of compliance with existing

regulations related to social issues, Hewlett-Packard advocates for policy changes and

supports congressional review of environmental standards, particularly around the firms

29

strengths. For example, a J une 2005, statement released by David Isaacs, Hewlett-

Packards Director of Government and Public Policy, lauded efforts by a subcommittee

of the US Senate Committee on Environment and Public works for its efforts to push for

new legislation in the area of Electronic Waste, suggesting ways that a bill under

consideration could leverage the capabilities and expertise of manufacturers to achieve

efficient and low cost opportunities for all customers while achieving environmentally

sound management of discarded IT products at the lowest possible cost, while

minimizing the role and burden on government.

In summary, Hewlett-Packard appears to have complemented its social

responsibility position with a lobbying strategy aimed at changing government policy in

ways that allow it to benefit from the companys existing social responsibility positions,

which were well in front of existing government regulation and policy at the time they

were initiated. By positioning themselves ahead of government regulation on social

issues, Hewlett-Packard appears to have been able to create sustainable value by lobbying

for government regulation that raised their rivals costs. On the Electronic Waste front,

Hewlett-Packard successfully advocated for taxing all manufacturers at the time of

electronics product sales for the cost of future recycling expenses; they were then able to

benefit from this by also advocating for government subsidies directed at electronic

product manufacturing firms that successfully recycled electronic products (whether the

company receiving the subsidy manufactured the original product or a competitor did).

At the time that Hewlett-Packard advocated for the policy changes, the company was

already in a position to benefit from the new policy, while their competitors were not as

well prepared.

30

6 Conclusion

In this research, I have shown that CSR and corporate political activity function as

economic complements rather than as economic substitutes. Specifically, I have shown

that while it is true that most socially irresponsible firms are more likely to have lobbied,

that it is also the case the most socially responsible firms are also more likely to have

lobbied. I have also shown that in regressions that compare different firms (between

tests), that lobbying intensity and CSR intensity both independently and jointly explain

why some firms have higher valuations than others. More importantly, however, I have

shown that in regressions that examine individual firms over time (within tests) that the

interaction between lobbying intensity and CSR quality explains higher valuations,

whereas CSR quality alone may lead to lower firm valuations. The result that the

interaction between CSR and corporate political activity remains positive and significant

in both between and within firm tests, unambiguously supports the hypothesis that the

two non-market strategies, CSR and corporate political activity, are complements.

My results bridge the findings between proponents of CSRwho build arguments

based on organizational stakeholder theories and who run between firms tests to find

empirical support that CSR increases firms valueand the results of critics of CSR

who build their arguments based on economic theories of shareholder wealth

maximization and who run within firm tests to find empirical support for the notion that

CSR does not enhance firm value and may actually destroy it. The reality is that both

the proponents of CSR and the critics of CSR have valid points; however, both have

overlooked the complementary relationship between CSR and corporate political activity.

When we add corporate political activity into the mix, we find that the proponents are

31

correct that CSR increases the value of the firm in some circumstances, despite the critics

also being correct that CSR by itself can decrease the value of the firm, since CSR only

adds value when complemented with the appropriate level of corporate political activity.

Moreover, my results have serious implications for our understanding of any

research on CSR or corporate political activity. If CSR and corporate political activity

are complementary activities pursued by firms, as this research has shown, we should no

longer consider the role of CSR or political activity alone without considering the role of

its complement, since doing so is likely to lead to biased results under most

circumstances. Researchers attempting to answer valuation-related questions on either

topic (CSR or corporate political activity) should ideally incorporate data on its

complement into the analysis. Unfortunately, doing so is often not realistic given data

availability constraints, in which case researchers should at least acknowledge how the

complementary relationship between CSR and corporate political activity may bias

results focused more narrowly on one of the two non-market strategies.

As a final thought, this research also suggests a greater need for researchers to

study cases of regulatory capture that while designed by industry primarily for its

benefit (Stigler 1971) may nevertheless promote positive social outcomes. Since CSR

and corporate political activity are complements, these should be precisely the cases in

which CSR is most profitable for firms.

32

7 References

Agrawal, A.; and, Knoeber, C. R. 1999. Outside Directors, Politics and Firm

Performance. Working Paper. Available on SSRN at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=85310

Ansolabehere, S.; deFigueiredo, J .; and, Snyder, J . 2003. Why is There so Little Money

in U.S. Politics? Journal of Economic Perspectives 17(1), 105-30.

Ansolabehere, S.; Snyder, J .; and Tripathi, M. 2002. Are PAC Contributions and

Lobbying Linked? New Evidence from the 1995 Lobby Disclosure Act. Business &

Politics (4):2, 2

Bagnoli, M.; and, Watts, S. G. 2003. Selling to socially responsible consumers:

Competition and the private provision of public goods. Journal of Economics &

Management Strategy 12(3):41945

Baron, D.P. 2009. A Positive Theory of Moral Management, Social Pressure, and

Corporate Social Performance. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy. 18: 7-

43.

Baron, D.P., Harjoto, M.A., and J o, J . 2009. The Economics and Politics of Corporate

Social Performance Stanford Rock Center for Corporate Governance Working Paper

No. 45.

Chatterji A.K.; Levine D.I.; and, Toffel M.W. 2009. How well do social ratings actually

measure corporate social responsibility? Journal of Economics and Management

Strategy. 18(1): 125169.

Chen, H.; Parsley, D; and Yang, Y. 2010. Corporate Lobbying and Financial

Performance Working Paper. Available on SSRN at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1014264

Claessens, S.; Feijen, E.; and Laeven, L. 2008. Political Connections and Preferential

Access to Finance: The Role of Campaign Contributions, Journal of Financial

Economics. 88(3): 554-580.

Dal B, E. 2006. Regulatory Capture: A Review. Oxford Review of Economic Policy.

22(2), 203-225.

Devinney, T. 2009. Is the Socially Responsible Corporation a Myth? The Good, Bad

and Ugly of Corporate Social Responsibility. Academy of Management Perspectives.

22(3), 44-56.

Griffin, J .J . and J .F. Mahon, 1997, The Corporate Social Performance and Corporate

Financial Performance Debate: Twenty-FiveYears of Incomparable Research, Business

and Society, 36(1), 531.

33

Fimsman, R.; Elfenbein, D.; and McManus, B. 2010. Charity as a substitute for

reputation: Evidence from an online marketplace. Working Paper. [Available online at:

http://www2.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/rfisman/CharitySubstitutesForReputation_042810.

pdf]

Friedman, M. 1970. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits

New York Times Magazine. September 13, 1970.

Hillman, A. J . and Keim, G. D. 2001. "Shareholder Value, Stakeholder Management,

and Social Issues: What's the Bottom Line?" Strategic Management Journal 22(2): 125-

139.

Lyon, T. P; and Maxwell, J . W. 2008. Corporate social responsibility and the

environment: A theoretical perspective. Review of Environmental Economics and

Policy. 2(2), 240-260.

Margolis, J .; Elfenbein, H.; and Walsh, J . 2009. Does it pay to be goodand does it

matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial

performance. Harvard Business School Working Paper.

McWilliams, A.; and, Siegel, D. 2000. Corporate social responsibility and financial

performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strategic Management Journal. (21),603-

609.

Milyo, J ; Primo, D.M.; and Groseclose, T.J . 2000. "Corporate PAC Contributions in

Perspective." Business and Politics 2(1): 7588.

Moon, J . J . 2007. Essays in empirical analysis of corporate strategy and corporate

responsibility. Dissertation at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

[Available at: http://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI3271854]

Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. 2003. "Corporate Social and Financial

Performance: A Meta-analysis." Organization Studies 24(3): 403-441.

Porter, M. E. and Kramer, M.R. (2002). "The Competitive Advantage of Corporate

Philanthropy." Harvard Business Review 80(12): 56-68.

Richter, B.K.; Samphantharak, K.; and Timmons, J .F. 2009. Lobbying and Taxes.

American Journal of Political Science. 53(4): 893-909.

Waddock, S.A. and Graves, S. B. 1997a. The Corporate Social PerformanceFinancial

Performance Link, Strategic Management Journal, 18, 303317.

Waddock, S. A. and Graves, S. B. 1997b. "Quality of Management and Quality of

Stakeholder Relations." Business & Society. 36(3): 250-279.

Wei, Z.; Xie, F.; and Zhang, S. 2005. Ownership Structure and Firm Value in China's

Privatized Firms: 1991-2001. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis.

40(1), 87-108.

34

8 Appendix

TABLE A - KLD Attributes within Issue Areas

Strength Concern

Generous Giving Tax Disputes

Innovative Giving Investment Controversies

Support for Housing Negative Economic Impact

Indigenous Peoples Relations Strength Indigenous Peoples Relations Concern

Non-U.S. Charitable Giving Other

Volunteer Programs

Support for Education

Other Strength

Strength Concern

Limited Compensation High Compensation

Ownership Strength Ownership Concern

Transparency Strength Transparency Concern

Political Accountability Strength Political Accountability Concern

Other Strength Accounting Concern

Other Concern

Strength Concern

CEO Employee Discrimination

Promotion Non-Representation

Board of Directors Other Concern

Family Benefits

Women/Minority Contracting

Employment of the Disabled

Progressive Gay/Lesbian Policies

Other Strength

Strength Concern

Union Relations Strength Union Relations Concern

No Layoff Policy Health and Safety Concern

Cash Profit Sharing Workforce Reductions

Involvement Pension/Benefits Concern

Strong Retirement Benefits Other Concern

Health and Safety Strength

Other Strength

Strength Concern

Beneficial Products & Services Hazardous Waste

Pollution Prevention Regulatory Problems

Recycling Ozone Depleting Chemicals

Alternative Fuels Substantial Emissions

Other Strength Agricultural Chemicals

Climate Change Policy

Other Concern

Strength Concern

Indigenous Peoples Relations International Labor Concern

Labor Rights Strength Indigenous Peoples Relations

Other Strength Burma

Mexico

Other Concern

Strength Concern

Quality Product Safety

R&D/Innovation Marketing/Contracting Controversy

Benefits to Economically Disadvantaged Antitrust

Other Strength Other Concern

E

m

p

l

o

y

e

e

R

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

E

n

v

i

r

o

n

m

e

n

t

H

u

m

a

n

R

i

g

h

t

s

P

r

o

d

u

c

t

Q

u

a

l

i

t

i

e

s

C

o

m

m

u

n

i

t

y

R

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

C

o

r

p

o

r

a

t

e

G

o

v

e

r

n

a

n

c

e

D

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

y

35

Figure A1 Empirical Kernel Density Function of KLD Scores, by Lobbying Status

.00

.04

.08

.12

.16

.20

.24

-14 -12 -10 -8 -6 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14

Sumof KLD Strengths/Concerns

...for Firms that do NOT Lobby

...for Firms that DO Lobby

D

e

n

s

i

t

y

Distribution of KLD Scores by Lobbying Status

36

Figure A2 Illustration of Substitutes:

Indifference Curve Oblique to Origin and MRS Equals a Constant

Figure A3 Illustration of Complements:

Indifference Curve Convex to Origin and MRS a Function of A, B

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- English MattersДокумент1 страницаEnglish MattersdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- 170 Eng 10Документ224 страницы170 Eng 10deepashajiОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- 12 Business Studies Impq CH08 ControllingДокумент9 страниц12 Business Studies Impq CH08 ControllingdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- 12 Business Studies Impq CH07 DirectingДокумент9 страниц12 Business Studies Impq CH07 DirectingdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- 38432reading 4Документ28 страниц38432reading 4deepashajiОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Stanengding Rules&OrdersДокумент130 страницStanengding Rules&OrdersdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- NWMP Engfull PackageДокумент38 страницNWMP Engfull Packagedeepashaji100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Police Injustice Responding Together To Chaengnge The StoryДокумент4 страницыPolice Injustice Responding Together To Chaengnge The StorydeepashajiОценок пока нет

- Commonlit Reading LiteratureДокумент77 страницCommonlit Reading LiteraturedeepashajiОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Pages Froebom Police StoriesДокумент17 страницPages Froebom Police StoriesdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- Marking Scheme ScienceSubject XII 2010Документ438 страницMarking Scheme ScienceSubject XII 2010Ashish KumarОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Englishtagore The Home-ComingДокумент5 страницEnglishtagore The Home-ComingdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Parliamentarengy ProcedureДокумент1 страницаParliamentarengy ProceduredeepashajiОценок пока нет

- Parliamentary Procedures: Local Action GuideДокумент2 страницыParliamentary Procedures: Local Action GuidedeepashajiОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- PSB Guidelinreadinges July2013Документ25 страницPSB Guidelinreadinges July2013deepashajiОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Parliamentary Procedure: Simplified Handbook ofДокумент23 страницыParliamentary Procedure: Simplified Handbook ofdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- Parliamentary Procedure - Quick Questions and Answers: T L C W S UДокумент4 страницыParliamentary Procedure - Quick Questions and Answers: T L C W S UdeepashajiОценок пока нет

- The Logic of Faith Vol. 1Документ39 страницThe Logic of Faith Vol. 1Domenic Marbaniang100% (2)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- C Programming StringДокумент5 страницC Programming StringJohn Mark CarpioОценок пока нет

- System Flyer PROSLIDE 32 B - V5.0 - 2020-03-09 PDFДокумент10 страницSystem Flyer PROSLIDE 32 B - V5.0 - 2020-03-09 PDFeduardoОценок пока нет

- Datasheet Solis 110K 5GДокумент2 страницыDatasheet Solis 110K 5GAneeq TahirОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Experiment6 Multiplexer DemultiplexerДокумент10 страницExperiment6 Multiplexer DemultiplexerAj DevezaОценок пока нет