Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

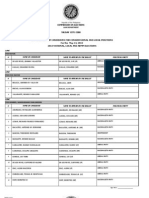

State of The Nation Address of Manuel Quezon Delivered in 1935

Загружено:

CebuDailyNewsОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

State of The Nation Address of Manuel Quezon Delivered in 1935

Загружено:

CebuDailyNewsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Message of His Excellency Manuel L.

Quezon President of the Philippines To the First National Assembly on National Defense [Delivered in the Assembly Hall, Legislative Building, November 25, 1935] Mr. Speaker, gentlemen of the National Assembly: As I appear before you for the first time, allow me to extend to you my cordial greetings and congratulations upon your election to this august body. It is your unique privilege to serve our country at the most critical period of its existenceat a time when the course of its destiny will be charted. The framers of our Constitution conferred upon our Government all the power and authority needed to meet the demands of a progressive and enlightened epoch so that it may be able to promote the welfare and happiness of our people and safeguard their liberty. I know you are well aware of the share of responsibility in the task of government which belongs to you. Unlike the Legislature that preceded you, which had two Houses, this National Assembly is by itself the whole Legislative Department of the government. When you take final action on a measure, there is no other legislative branch that will pass upon and give it further consideration. The measure as you pass it goes directly to the Chief Executive, who is devoid of any power to alter it in any way and has no alternative except that of giving it his express or implied approval, or of vetoing it. In my opinion, the main responsibility for legislative action is yours. It will be my policy as Chief Executive to give you, in every case, the benefit of doubt. You may, therefore, rest assured that, if ever, I shall exercise my veto power with reluctance, and only when I am strongly convinced that it is my plain and unavoidable duty to do so in the interest of the common weal. Article VII, section 11, (5) of the Constitution directs the President to present to the National Assembly, from time to time, information on the state of the Nation, and to recommend to its consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient. In the fulfillment of this duty, I am addressing the National Assembly today on the fundamental responsibility of a stateon a question involving our very existence when we become a free member of the family of nations. This question is that of assuring the future safety of our beloved country. Self-defense is the supreme right of mankind, no more sacred to the individual than to the nation, the interests of which are immeasurably of greater significance and extent. A threat against the nation involves not alone the life of one individual, but of millions; not the welfare and fortune of a single family, but of all. And above everything else, depending upon the exercise of the right of national self-defense is freedom itself, the most precious reward from Heaven to the worthy. This immutable principle is firmly incorporated in our Constitutionthe Magna Charta of Philippine Liberty. We, the citizens of these Islands, are now fairly started upon the final stretch of the long road we have so patiently and persistently followed toward the goal of independence. Up to here the trail has been a tortuous one. But the difficulties we have encountered and the frustrations we have endured have not deterred us from our purpose. They have served only to spur us onwardto increase the intensity of our undying devotion to the cause for which no cost could be too great, no sacrifice too bitter. And now at last, with success so plainly in our sight, our love of liberty and the voice of reason alike urge us to guard and cherish the prize that has been so hardly won.

I would be recreant to my duty did I not come to you, in my first appearance before the National Assembly, to ask your ungrudging support for the establishment of a sound system of National Defense. This is our first and most urgent need. As we commit ourselves to this important task we realize that a war-weary world groans under a burden of armaments. Every accretion to the accumulated total is invariably subjected to careful and even suspicious scrutiny. But the world must be well aware that in the present state of our development, the establishment within these Islands of an aggressive force capable of threatening the security of any other nation would be fantastic. Consequently, without fear that any act of ours may be misunderstood or resented by others, we are free to undertake every preparatory measure of defense that the circumstances of our situation may require. Nevertheless, it is well that we now announce, through clear delineation of our objective, definite limits upon the efforts we shall make in this direction. That objective is a single one peacepermanent peace! This objective is proclaimed in our own Constitution and no Filipino dares to challenge it. No purpose of our own, no conceivable temptation or manipulation from abroad, can ever lead us into war save in defense of our own rights, waged within the limits of our own territory. Our full desire is to insure domestic tranquillity and to guarantee to our citizens the opportunity to pursue, without external molestation, prosperity and happiness under a stable government, devised, developed, and maintained by the people themselves. In furtherance of this purpose I shall submit to you a comprehensive plan for national defense. In my opinion the plan reflects the lessons of history, the conclusions of acknowledged masters of warfare and of statesmanship, and the sentiments and aspirations of the Filipino people. It is founded upon enduring principles that are fundamental to any plan applicable to our needs. The first of these principles is that every citizen is obligated to the nations defense. All the individual and national resources may be used by the State in the interest of self-preservation. No man has the inalienable right to enjoy the privileges and opportunities conferred upon him by free institutions unless he simultaneously acknowledges his duty to defend with his life and with his property the Government through which he acquires these opportunities and these privileges. To deny this individual responsibility is to reject the whole theory of democratic government. This principle knows no limitation of time or condition. It is effective in war, in peace, and for as long as the nation shall endure. Impelled by cogent reasons I propose its specific application to our peace-time task of preparation, by requiring every citizen of suitable age and physique to undergo military training as an obligation to the State. The ultimate bulwark of liberty is the readiness of free citizens to sacrifice themselves in defense of that boon. Where this spirit has been inculcated through generations and has become firmly embedded in the public consciousness, nations have been strong, virile, prosperous, and stable. Where citizens have grown neglectful of this individual obligation, especially where they have sought to deny its validity, the result has been decadence, weakness, poverty, and destruction. To foster national pride and patriotism nothing is more effective than to participate actively in the processes of maintaining the national defense. Military training and service build up the spirit of duty and love of country. They nurture patriotism, loyalty, courage, and discipline. A nation of trained men ready to defend their country has the lasting respect of itself and of the world. A nation of helpless citizens can expect nothing but slavery at home, and contempt abroad. If we are wise, if we are mindful of the lessons history teaches, we will provide a military education for our entire manhood, beginning from early adolescence. To accomplish this purpose a utilization of the public-school system immediately suggests itself. By inculcating in rising generations the soldierly virtues, by preparing our people spiritually and physically to serve the state, our schools will be building upon solid foundations not only national

consciousness and solidarity but also boldness of spirit which are indispensable to the free and uninterrupted development of this nation. The second basic principle is that our national defense system must provide actual security. Indeed, an insufficient defense is almost a contradiction in terms. A dam that crumbles under the rising flood is nothing more than a desolate monument to the wasted effort and lack of vision of its builders. In this one function of government there can be no compromise with minimum requirements. Our program of national defense must serve notice upon the world that the citizens of these Islands are not to be subjugated; that conquest of this nation cannot be accomplished short of its utter destruction, and that that destruction would involve such staggering cost to an aggressor, both in blood and gold, that even the boldest and the strongest will unerringly mark the folly of such an undertaking. The next principle to which I hold is the insistent need for current and future economy. Although there are no costs of peace comparable to those that would surely follow defeat in war, it is nevertheless incumbent upon the Government to avoid every unnecessary expenditure. During the three centuries of Philippine history as a dependency, there have been largely lifted from our shoulders the burdens incident to sovereignty, particularly those of providing for our own protection. These burdens our people now gladly accept. They stand ready to pay the cost, whatever it may be, of assuring the permanent security and integrity of the homeland. But for us in the Government, to permit this cost to exceed the minimum demanded by the purpose that we seek would be an inexcusable blunder and a betrayal of the trust reposed in us. The need for minimizing expense not only requires the utmost efficiency in details, but also it clearly indicates the basic character of the defensive establishment we must devise. Specifically, it precludes, for the present at least, the development of a battle fleet. Naval strength is expressed principally in terms of fighting ships, each of which, even in the small and auxiliary categories, can be produced only at tremendous cost. It is manifestly impossible, in the current state of our economic development, to acquire a fleet that could offer even partially effective resistance to any existing navy worthy of the name. One desirable effect of a decision to forego the construction of a battle fleet will be to emphasize the passively defensive character of our military establishment. Tactically, a fleet cannot operate as a purely defensive force and is useless unless it can proceed to see and engage its enemy beyond the limits of its own bases. Moreover, the existence of a powerful navy inherently implies a possibility of aggressive intent, since only with strong naval support could an army hope to invade the territory of an overseas enemy. Consequently, as an island nation, our lack of sea power will confirm before the world our earnest intent to develop an army solely for defensive purposes. Another fundamental premise is the necessity for a gradual rather than sudden growth of the required defense establishment. Both economy and efficiency demand no immediate and complete organization of a force of the necessary eventual strength. A modern army is a complex organism, and its defensive power is not measured solely by the number of its soldiers. Suitable armament, proper organization, professional technique and skill, applicable tactical doctrine and, above all, trained leadership are the very soul of an armys combat efficiency. However lavish may be the expenditure, these things cannot be instantly acquired. They are brought about only through thoughtful, painstaking, and persistent effort, intelligently directed. Progress in these fields will determine the rate at which the whole development, including increases in personnel strength, may logically and efficiently proceed. Nevertheless, it is imperative that our plans reach fruition by the time the beneficent protection of the United States shall have been finally withdrawn. We have ten years, and only ten, in which to initiate and complete the development of our defensive structure, the creation of which, because of the conditions of our past existence, must now begin at the very foundations. Not a moment is to be lost. Starting immediately, we must build economically and gradually, but steadily and surely, so as to attain within the time permitted us the highest possible efficiency at the lowest possible cost.

Finally, I must emphasize the need for logical governmental procedure in this development a procedure calculated to minimize error and to avoid loss of time, waste of resources, and unnecessary exposure of the country to the risks of unpreparedness. Since our security arrangements must be carefully moulded to fit the special and particular needs of our country, there exists nowhere in the world a model upon which our own defenses may be blindly patterned. Step by step we must design a new organism, and in doing so we must advance progressively from the general to the specific; from the explored to the unexplored. A continuous adjustment of essential details to constantly evolving requirements will be mandatory. Such a procedure will be possible only through the exercise of administrative authority, taking advantage of the highest professional and technical advice. But since under our form of government, administrative authority is limited to the task of execution, it is highly important that initial legislation for the erection of the nations defenses should confer upon the President as Commander -in-Chief, a very considerable latitude in carrying out the expressed purposes of the National Assembly. Any attempt, at the outset of this undertaking, to formulate a plan that would prescribe in concrete and inflexible language every detail of the complete development could not fail to result in added cost and slow progress. The essential elements of our defensive system will in time become more clearly crystallized and definitely moulded to the needs of the nation. Then, it will be time for the National Assembly to enact legislation with such details as it may deem desirable. But though details of design in the superstructure of defense should, at least for the present, be charged to the Chief Executive, the Assembly must retain the responsibility of assuring the soundness of its foundations. It is not only the prerogative but also the duty of the Legislative Department to evolve and to prescribe the broad policies that are to control progress in this critically important task. Likewise it is a function of the Legislative Body to bestow specific authorization and to provide the funds essential to the purpose it seeks. Supported by such authority and guided by these policies, the Chief Executive will be enabled to proceed confidently and expeditiously toward the accomplishment of the legislative intent. The central feature of the defensive system I propose is a trained and organized force, normally engaged in the pursuits of peace, and ready for effective employment whenever the interests of the nation so demand. Service in this force is to be rendered as a patriotic obligation to the state. Upon reaching maturity, each able-bodied male citizen will automatically become liable for a period of intensive military training. From the number annually attaining this age, a training quota of the required size will be selected by lot. Moreover, so far as the capacity of the Army will permit, volunteers from among those not so selected, or from older age groups, will be incorporated into the training cadres. Upon completion of his training period, each citizen will return to civil life, but as a member of an Army reserve unit. Thus the burden of defense will be widely distributed, and each citizen will devote to exclusive military activity only an insignificant portion of his time. The regular element of the Army, composed of volunteers from every geographical area of the Islands, will eventually attain a maximum strength of 1,500 officers and 19,000 enlisted men, including the existing Constabulary. Its officers and men will pursue the military profession as a lifes career and devote themselves exclusively to the nations defense. The Regular Army must become a model of efficiency the energizing element and, professionally, the directing head of the whole establishment. Its missions will comprehend the maintenance of permanent overhead for the entire force, including such essential services as procurement, storage, transportation, communication, and sanitation; the prosecution of research and experimentation to keep the Army abreast of latest developments in every branch of the military profession; and instruction of the reserve. In organizational and operational outline the proposed system is the essence of simplicity. Under its provisions the Chief of Staff of the Army is selected by and is directly responsible to the President, and will have the rank of a Secretary of Department. Under him will be a Department of National Defense comprising the several staff sections required for general supervision of the whole military establishment and for the control of administration, training, maintenance, and other essential functions.

The reserve units will be dispersed through all the Islands, approximately according to population. The national territory will be divided into military districts and subdistricts, in each of which will be maintained a small professional cadre for the training of the annual quota locally called to the colors. Training periods except for trainees selected to serve with the Regular Force will normally extend over a period of five and a half months. Thereafter, for ten years, each trainee will be required to undergo annually sufficient training to preserve individual and collective efficiency. From that time onward his training will grow progressively less. Under this system we will have, within ten years, hundreds of thousands of trained individuals, and eventually practically the entire male population will have had military training. The younger men of this group will be constantly organized into tactical formations. Supporting these units will be a pool of trained individuals, generally in higher age groups, but available in emergency for replacements in line organizations or for employment in staff services. Equipment and supplies for reserve organizations will be locally stored and maintained, under the control of professionally trained cadres. Supplementing the training given in the Army will be the military instructional system in schools and colleges. Every educational institution wholly or partially supported at public expense is to serve, under the plan, as an agency for inculcating patriotism and for assisting in the important work of instructing our people in the essentials of the military profession. Starting with students, aged ten, intensive courses in citizenship, sanitation, and physical development will be progressively widened in scope during the period of adolescence, until at the age of eighteen, every able-bodied male student will have pursued a thorough course in elementary military practices and methods. As a consequence, even though quotas annually trained in the Army will comprise only a portion of the young men attaining the age of twenty-one, we will eventually acquaint our entire male population with the essential requirements of military service. The plan provides a comprehensive system for the emergency mobilization of the reserves so as to insure rapid, concerted, and efficient action in the face of emergency. It proposes yearly objectives in the procurement of armaments and equipment. All these things and many others, I have developed in as exhaustive detail as is now possible, to the end that my proposals to the National Assembly might comprise concrete rather than theoretical recommendations. Although, in broad outline, the proposed system of defense may be thus briefly and accurately described, the governmental problems involved in transforming plans into actual accomplishment will be almost baffling in their intricacy and difficulty. Preliminary to undertaking actual development, necessary laws must be formulated and approved, and initial selections of higher military officials accomplished. Thereafter, and in full accord with the provisions of these legislative enactments, the professional and technical phases of the task will begin. Merely to name the more important of them is to indicate clearly the involved character of the project. Organization of the Department of National Defense must aim at efficient functioning, but must avoid extravagance entailed by the maintenance of unnecessary overhead. Its membership must possess the qualifications required by the purpose of each essential bureau, including those, for example, pertaining to armament, administration, supply, sanitation, and legal affairs. An efficient officer corps is the very soul of an army. To produce one of the requisite size and qualifications we must first provide for its gradual accumulation, so that future turn-over will involve only a small annual increment. We must evolve policies governing appointments, promotion, pay, assignment, and retirements, and must provide for the thorough military education of its members. Technical schools must be established, and for these the faculties must first be organized and thoroughly indoctrinated. Suitable tactical organization of the Army, accurately adjusted to the necessities of Philippine conditions, must be developed. Applicable doctrine and method must be evolved. A skeletonized organization for registration of citizens subject to military training, and for receiving, caring for and training annual quotas must be established. Necessary programs pertaining to munitions, including such technical items as

airplanes, rifles, cannon, machine guns, ammunition, signal equipment, bridging material, and a host of other matters must be formulated in accordance with our minimum needs. Inspection, accounting, and other phases of administration must be established and maintained. All these constitute immediate problems for which solutions must develop side by side, each fully articulated and synchronized with all others. This necessary control, direction, and coordination of a myriad of essential details represents one of the most difficult and critical problems of the entire project. In its importance to progress, it will, for some years to come, overshadow all others. For its successful solution there is immediately demanded, not only a technical ability that extends to every phase of the military profession, but also a broad and thorough experience in the field of higher administration, organization, and leadership. Unless these qualifications can be made constantly available to the Commonwealth we will pay for their lack in millions of squandered pesos, years of wasted time, and in confusion of effort and added risks to our nations security. Unfortunately it is this type of ability and experience that, as yet, there has been little opportunity to develop among our own people. We have produced, both in the Constabulary and in the Philippine Scouts, officers of outstanding worth in particular lines of military endeavor, from among whom we confidently expect to obtain initially the senior officers of the new Army. But due to the conditions of our past existence we have had no War Department, no complete defense force, no balanced army, no exclusive responsibility for protection, and, consequently, no experience in the functions that now assume for us a transcendent importance. In this situation we have no alternative but to obtain this experience, this ability, and this skill from other sources, and in my anxiety on this score I earnestly considered all upon which we might logically depend. Every consideration of friendship and association supported the hope that this source might be the United States. Consequently, I presented to the President of that country the essentials of this problem and explained our dire need for help. More specifically I earnestly requested the detail of General Douglas MacArthur, then Chief of Staff of the United States Army, as the one soldier whose opinion on every question of military organization would command the respect of all our people. The Presidents response was immediate, sympathetic, and definite. At a very real sacrifice to the American Army this officer, who since 1930 had served continuously as its Chief of Staff, has been made available to the Commonwealth Government as Military Adviser. His record in peace and war requires no eulogy from me. His qualifications for the important post in which he will serve are as clearly appreciated among our own people as they are in Washington. Because of this, and because also of his own known devotion to the Philippines and to the Filipino people, the wisdom of his choice will be universally recognized. I request authority to confer upon General MacArthur and his assistants the rank and emoluments that I deem in keeping with their important duties and the dignity of this nation. The several provisions of law fundamental to the development of Philippine defense are outlined in a draft of a bill which I shall presently furnish you. It depicts, in much greater detail than I have attempted here, the defense plan I propose for adoption. It represents the essence of the authorizations, directives, and general policies necessary to insure initiation of the project. Again, I emphasize the need for prompt and positive action in initiating this great project. In every other line of human endeavor we have built, not only the foundations, but also the framework and, in certain cases, even the edifice itself. But here, except for necessary law enforcement elements, not a stone has been laid.

The refusal to grant us immediate and complete independence has been due, in large measure, to our present inability to cope with a general revolt or to offer any kind of resistance to an invading force. Your swift action on the defense measures I am proposing will prove the earnestness of our determination to be, and forever to remain, free and independent. What, I ask, would be the use of seeing our country free one day, with its own flag standing alone and flying against the sky, only to see ourselves the subjects of another power the following day, with its flag the sovereign in and of our country? What would be the purpose of educating our young men and women concerning their rights and privileges as free citizens, if tomorrow they are to be subjects of a foreign foe? Why build up the wealth of the Nation only to swell up the coffers of another? If that be our preordained fate, why seek a new master when the Stars and Stripes has given us not only justice and fair treatment, welfare and prosperity, but also ever increasing political liberties including independence? National freedom now stands before us as a shining light the freedom that for many years gleamed only fitful candle in the distant dark. We shall make ourselves ready to grasp the torch, so that no predatory force may ever strike it from our hands! (Source: www.gov.ph)

Вам также может понравиться

- Eisenhower Alex MainДокумент6 страницEisenhower Alex MainThiago HenriqueОценок пока нет

- President Dwight D Eisenhower's Farewell Address I961Документ5 страницPresident Dwight D Eisenhower's Farewell Address I961mish_ranuОценок пока нет

- Military-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961Документ5 страницMilitary-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961john-eagleland2Оценок пока нет

- Eisenhower's Farewell Address To The Nation: January 17, 1961Документ5 страницEisenhower's Farewell Address To The Nation: January 17, 1961Alexander AlltimeОценок пока нет

- Military-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961Документ4 страницыMilitary-Industrial Complex Speech, Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961Carl CordОценок пока нет

- Manuel Quezon's First Inaugural AddressДокумент3 страницыManuel Quezon's First Inaugural AddressFrancis PasionОценок пока нет

- A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents Volume 8, part 2: Grover ClevelandОт EverandA Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents Volume 8, part 2: Grover ClevelandОценок пока нет

- Eisenhowers Farewell AddressДокумент3 страницыEisenhowers Farewell Addresstimothyjgraham1445Оценок пока нет

- Speech of President CarlosДокумент3 страницыSpeech of President CarlosKenzii LopezОценок пока нет

- SpeechДокумент6 страницSpeechVirna CuntapayОценок пока нет

- Inaugural Address of Franklin Delano Roosevelt / Given in Washington, D.C. March 4th, 1933От EverandInaugural Address of Franklin Delano Roosevelt / Given in Washington, D.C. March 4th, 1933Оценок пока нет

- נאום הפרידה של הנשיא אייזנהאוארДокумент4 страницыנאום הפרידה של הנשיא אייזנהאוארa1eshОценок пока нет

- Gettysburg AddressДокумент3 страницыGettysburg Addresswatermelon sugarОценок пока нет

- Works of Franklin DДокумент4 страницыWorks of Franklin Djeubank4Оценок пока нет

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt's First Inaugural AddressОт EverandFranklin Delano Roosevelt's First Inaugural AddressОценок пока нет

- Quezon Fourth State of The Nation Address 1939Документ9 страницQuezon Fourth State of The Nation Address 1939malacanangmuseumОценок пока нет

- Abridged Version of The Inaugural Address of His Excellency Ramon MagsaysayДокумент2 страницыAbridged Version of The Inaugural Address of His Excellency Ramon MagsaysayAngelica Magcalas Mercado0% (1)

- FDR InauДокумент3 страницыFDR InauParvez AhamedОценок пока нет

- Federalist No. 15: The Insufficiency of The Present Confederation To Preserve The UnionДокумент4 страницыFederalist No. 15: The Insufficiency of The Present Confederation To Preserve The UnionnscheindlinОценок пока нет

- Decide One Part That Each of You Will Deliver in ClassДокумент3 страницыDecide One Part That Each of You Will Deliver in ClassSouthwill learning centerОценок пока нет

- 1956 Republican Party PlatformДокумент32 страницы1956 Republican Party PlatformEphraim DavisОценок пока нет

- First Inaugural Speech by Franklin D RooseveltДокумент4 страницыFirst Inaugural Speech by Franklin D RooseveltX RyugaОценок пока нет

- Franklin Roosevelt First Inaugural Address (1) 5306800408576500Документ4 страницыFranklin Roosevelt First Inaugural Address (1) 5306800408576500Kinyua Wa IrunguОценок пока нет

- 17.2 - First Inaugural Address of Franklin D. RooseveltДокумент4 страницы17.2 - First Inaugural Address of Franklin D. RooseveltPablo DavidОценок пока нет

- Franklin Delano Roosevel1ppДокумент6 страницFranklin Delano Roosevel1ppspaceogОценок пока нет

- PaulДокумент2 страницыPaulMohammed Imran KhanОценок пока нет

- First Inaugural AddressДокумент8 страницFirst Inaugural AddressPaulo FilhoОценок пока нет

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Farewell AddressДокумент6 страницPresident Dwight D. Eisenhower's Farewell AddressREBogartОценок пока нет

- Schlesinger, James R. - January 1976, 102-1-875Документ2 страницыSchlesinger, James R. - January 1976, 102-1-875samlagroneОценок пока нет

- Speech About The Illuminati (NWO) - President J. F. KennedyДокумент2 страницыSpeech About The Illuminati (NWO) - President J. F. KennedyEyemanProphetОценок пока нет

- InadresssdocДокумент4 страницыInadresssdocapi-207714611Оценок пока нет

- CWTS ReviewerДокумент15 страницCWTS Reviewerblahblahblacksheep76Оценок пока нет

- Presidential Inaugural SpeechesДокумент74 страницыPresidential Inaugural SpeechesRG CruzОценок пока нет

- Army Act: July 18, 2018Документ2 страницыArmy Act: July 18, 2018Asif Khan ShinwariОценок пока нет

- Rph-Notes 3Документ17 страницRph-Notes 3Mark BunsalaoОценок пока нет

- 08 Republican PlatformДокумент67 страниц08 Republican PlatformAmberОценок пока нет

- FDR Inaugural SpeechДокумент3 страницыFDR Inaugural SpeechMarandaОценок пока нет

- Primary Source Worksheet: George Washington, Farewell Address, 1796Документ4 страницыPrimary Source Worksheet: George Washington, Farewell Address, 1796OmarОценок пока нет

- "The State of The Nation" Message To Congress of His Excellency Elpidio Quirino President of The PhilippinesДокумент14 страниц"The State of The Nation" Message To Congress of His Excellency Elpidio Quirino President of The PhilippinesmalacanangmuseumОценок пока нет

- Address of President Manuel LДокумент4 страницыAddress of President Manuel LjesielzОценок пока нет

- Inaugural Address of Jose P. LaurelДокумент6 страницInaugural Address of Jose P. LaureljohnОценок пока нет

- Article 2 Declaration of Principles and State PoliciesДокумент3 страницыArticle 2 Declaration of Principles and State PoliciesKris BorlonganОценок пока нет

- FDR 1st AddressДокумент9 страницFDR 1st AddressNiteesh KuchakullaОценок пока нет

- Consti 1 Reviewer Chap 1-12Документ16 страницConsti 1 Reviewer Chap 1-12james_ventura_1Оценок пока нет

- UniversalPeoplesDeclarationofFreedom DistributionДокумент3 страницыUniversalPeoplesDeclarationofFreedom DistributionSeedingRevolutionОценок пока нет

- Full Download Test Bank For Security Policies and Procedures Principles and Practices 0131866915 PDF Full ChapterДокумент34 страницыFull Download Test Bank For Security Policies and Procedures Principles and Practices 0131866915 PDF Full Chapterflotageepigee.bp50100% (18)

- Untitled Document 1Документ3 страницыUntitled Document 1Timothy AngОценок пока нет

- Omaha Platform 1892Документ5 страницOmaha Platform 1892Jeff SmithОценок пока нет

- Citizenship Governance: and GoodДокумент73 страницыCitizenship Governance: and GoodAbby Gaile Lopez100% (1)

- Taped Baby Senate ResolutionДокумент2 страницыTaped Baby Senate ResolutionCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Consolidated Stranded Vessels, Passengers and CargoesДокумент4 страницыConsolidated Stranded Vessels, Passengers and CargoesCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Bus Pick-Up PointsДокумент1 страницаBus Pick-Up PointsCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Physician Licensure Exam 2014 ResultsДокумент46 страницPhysician Licensure Exam 2014 ResultsCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Presidential Assistant For Rehabilitation and Recovery Secretary Panfilo M. Lacson's Speech at The Presentation and Approval of Yolanda Rehabilitation PlansДокумент2 страницыPresidential Assistant For Rehabilitation and Recovery Secretary Panfilo M. Lacson's Speech at The Presentation and Approval of Yolanda Rehabilitation PlansCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Physician Board Exam Top Performing SchoolsДокумент2 страницыPhysician Board Exam Top Performing SchoolsTheSummitExpress100% (1)

- Alcoy, CebuДокумент2 страницыAlcoy, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Ironman Race Map in Cebu CityДокумент4 страницыIronman Race Map in Cebu CityCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Storm Surge Brought by Tropical Depression DomengДокумент3 страницыStorm Surge Brought by Tropical Depression DomengCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- President Benigno Aquino III State of The Nation Address 2013Документ25 страницPresident Benigno Aquino III State of The Nation Address 2013CebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Cebu City Engineering 3-YEAR PROGRAMДокумент77 страницCebu City Engineering 3-YEAR PROGRAMCebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- San Remigio, CebuДокумент2 страницыSan Remigio, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Marine Protests of MV St. Thomas Aquinas and MV Sulpicio SieteДокумент4 страницыMarine Protests of MV St. Thomas Aquinas and MV Sulpicio SieteCebuDailyNews70% (10)

- The State of The Nation Address of Sergio Osmena in 1945Документ7 страницThe State of The Nation Address of Sergio Osmena in 1945CebuDailyNewsОценок пока нет

- Tudela, CebuДокумент2 страницыTudela, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Alegria, CebuДокумент2 страницыAlegria, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Aloguinsan, CebuДокумент2 страницыAloguinsan, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Asturias, CebuДокумент2 страницыAsturias, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Argao, CebuДокумент2 страницыArgao, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Tabuelan, CebuДокумент2 страницыTabuelan, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Tabogon, CebuДокумент2 страницыTabogon, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Tuburan, CebuДокумент2 страницыTuburan, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Badian, CebuДокумент2 страницыBadian, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Alcantara, CebuДокумент2 страницыAlcantara, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Talisay City, CebuДокумент2 страницыTalisay City, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Santa Fe, CebuДокумент2 страницыSanta Fe, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Sogod, CebuДокумент2 страницыSogod, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Malabuyoc, CebuДокумент2 страницыMalabuyoc, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- Toledo City, CebuДокумент2 страницыToledo City, CebuSunStar Philippine NewsОценок пока нет

- APA CitationsДокумент9 страницAPA CitationsIslamОценок пока нет

- Project TitleДокумент15 страницProject TitleadvikaОценок пока нет

- Extinct Endangered Species PDFДокумент2 страницыExtinct Endangered Species PDFTheresaОценок пока нет

- Sample Behavioral Interview QuestionsДокумент3 страницыSample Behavioral Interview QuestionssanthoshvОценок пока нет

- BP TB A2PlusДокумент209 страницBP TB A2PlusTAMER KIRKAYA100% (1)

- IndianJPsychiatry632179-396519 110051Документ5 страницIndianJPsychiatry632179-396519 110051gion.nandОценок пока нет

- Political and Institutional Challenges of ReforminДокумент28 страницPolitical and Institutional Challenges of ReforminferreiraccarolinaОценок пока нет

- DLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingДокумент2 страницыDLP No. 10 - Literary and Academic WritingPam Lordan83% (12)

- Materials System SpecificationДокумент14 страницMaterials System Specificationnadeem shaikhОценок пока нет

- Marriage Families Separation Information PackДокумент6 страницMarriage Families Separation Information PackFatima JabeenОценок пока нет

- Q3 Grade 8 Week 4Документ15 страницQ3 Grade 8 Week 4aniejeonОценок пока нет

- Industrial Visit Report Part 2Документ41 страницаIndustrial Visit Report Part 2Navratan JagnadeОценок пока нет

- KalamДокумент8 страницKalamRohitKumarSahuОценок пока нет

- Purposeful Activity in Psychiatric Rehabilitation: Is Neurogenesis A Key Player?Документ6 страницPurposeful Activity in Psychiatric Rehabilitation: Is Neurogenesis A Key Player?Utiru UtiruОценок пока нет

- Veritas CloudPoint Administrator's GuideДокумент294 страницыVeritas CloudPoint Administrator's Guidebalamurali_aОценок пока нет

- International Covenant On Economic Social and Cultural ReportДокумент19 страницInternational Covenant On Economic Social and Cultural ReportLD MontzОценок пока нет

- Fry 2016Документ27 страницFry 2016Shahid RashidОценок пока нет

- W2-Prepares Feasible and Practical BudgetДокумент15 страницW2-Prepares Feasible and Practical Budgetalfredo pintoОценок пока нет

- Research Report On Energy Sector in GujaratДокумент48 страницResearch Report On Energy Sector in Gujaratratilal12Оценок пока нет

- Session Guide - Ramil BellenДокумент6 страницSession Guide - Ramil BellenRamilОценок пока нет

- On The Linguistic Turn in Philosophy - Stenlund2002 PDFДокумент40 страницOn The Linguistic Turn in Philosophy - Stenlund2002 PDFPablo BarbosaОценок пока нет

- Effect of Added Sodium Sulphate On Colour Strength and Dye Fixation of Digital Printed Cellulosic FabricsДокумент21 страницаEffect of Added Sodium Sulphate On Colour Strength and Dye Fixation of Digital Printed Cellulosic FabricsSumaiya AltafОценок пока нет

- Motion Exhibit 4 - Declaration of Kelley Lynch - 03.16.15 FINALДокумент157 страницMotion Exhibit 4 - Declaration of Kelley Lynch - 03.16.15 FINALOdzer ChenmaОценок пока нет

- Discrete Probability Distribution UpdatedДокумент44 страницыDiscrete Probability Distribution UpdatedWaylonОценок пока нет

- Wetlands Denote Perennial Water Bodies That Originate From Underground Sources of Water or RainsДокумент3 страницыWetlands Denote Perennial Water Bodies That Originate From Underground Sources of Water or RainsManish thapaОценок пока нет

- What Is A Designer Norman PotterДокумент27 страницWhat Is A Designer Norman PotterJoana Sebastião0% (1)

- Maule M7 ChecklistДокумент2 страницыMaule M7 ChecklistRameez33Оценок пока нет

- Account Intel Sample 3Документ28 страницAccount Intel Sample 3CI SamplesОценок пока нет

- Deadlands - Dime Novel 02 - Independence Day PDFДокумент35 страницDeadlands - Dime Novel 02 - Independence Day PDFDavid CastelliОценок пока нет

- Personal Training Program Design Using FITT PrincipleДокумент1 страницаPersonal Training Program Design Using FITT PrincipleDan DanОценок пока нет