Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

M.G. Vassanji's The Assassin's Song: The In-Between World of Karsan Dargawalla

Загружено:

Siddhartha SinghОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

M.G. Vassanji's The Assassin's Song: The In-Between World of Karsan Dargawalla

Загружено:

Siddhartha SinghАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Priyanka Singh

Research Scholar Deptt. of English & Modern European Languages, University of Allahabad, Allahabad. M.G. Vassanji's The Assassin's Song: The In-Between World Of Karsan Dargawalla

A diaspora1 writer today faces demanding affiliations of languages, class race, gender and sexuality which are manifested at emotional, cultural, ethnic, linguistic or political levels. A condition of reality or a state of mind for him- which is always in a flux - is often compounded by the exigencies of exile, migration, and double migration. As a result his affiliations are always faced with a varied degree of ambivalences. Thus the identity of a diaspora writer is challenged and ruptured by a multiplicity of ambivalent affiliations that avail or impose themselves. He is always confronted with a destabilizing polemical situation of "in-betweenness". Moyez Gulam Hussein Vassanji is one of the most important Indo-Canadian diasporic writers, whose novels constantly articulates and grapples with this polemics of "inbetweenness" and the latest example is The Assassins Song which shall be the focus of this article. I M.G. Vassanji, whose forefathers were migrated from India under indenture system 2 in colonial rule, was born in Nairobi, Kenya in 1950. His family left for Dar es Salaam in Tanzania at the end of the Mau Mau period.3 The United Republic of Tanzania came into being in 1964. Those were the times of economical setback and political unrest of the entire African continent. The indigenous Africans had a very hostile attitude towards Indians whose situation was like a "colonial sandwich", with the European at the top and Africans at the bottom. Amid increasing resentment of the Africans many Indians fled to England, Europe and North America to avoid racial and

[2]

political discriminations. Vassanji, at the age of 19, left the University of Nairobi on a scholarship to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After earning a doctorate in Physics from the University of Pennsylvania and working as a writer- in-residence at the University of Iowa in the International Writing Program, he migrated to Canada and worked at the Chalk River Power Station for some time. Finally he came to Toronto in 1980 and accepted Canadian Citizenship in 1983. In 1989 his first novel The Gunny Sack was published. That year he, with his wife Nurjehan Aziz founded and edited the first issue of The Toranto South Asian Review (TSAR). Apart from The Gunny Sack Vassanji has penned five more novels; No New Land (1991), The Book of Secrets (1994) (which won the very first Scotiabank Giller Prize) , Amriika (1999) , In-Between World of Vikram Lall (2003)(which also received the Scotiabank Giller Prize) and The Assassins Song (2007). Vassanjis works, except the latest one, deal with diasporic Indians living in East Africa and their further migration to other places. Vassanji is concerned with how these migrations affect the life and identity of such dislocated lives. As a secondary theme, members of his community of Indian Muslims of the esoteric Shamsi sect (like himself) later undergo a second migration to Europe, Canada, or the United States. Vassanji explores the impact of these migrations on these characters who are installed as a buffer zone between the indigenous Africans and colonial administration. Caught in-between an ambivalent situation the presence of the mythical homeland India looms large. Not only for the characters but also for the writer himself India is a spiritual issue. This issue becomes more apparent in his latest work.

II Vassanji's The Assassin's Song

4

explores the conflict between ancient

loyalties and Modern desires, between legacy and discovery, between filial obligations and personal yearnings. This novel portrays the complexities of an individual conscience torn between responsibilities to uphold

[3]

tradition and desire to pursue ambition. It is a shining study of one man's painful struggle to hold the earthly desires and spirituality in balance. The Assassin's Song conspicuously depicts the horrific real-life communal killing in 2002 Gujarat riot, which destroys the lives of a thousand human beings. The Assassin's Song is the story of Karsan Dargawalla, a Khoja (a community which is a minority within a minority) and the heir of Pirbaag shrine worshipped by both Hindus and Muslims. Pirbaag traces roots to an ancient Sufi Nur Fazal whose teachings are concerned with both the mystical branches of Islaam and Hinduism. Karsan has just returned from North America to his homeland which he has left thirty years ago in order to choose a career in foreign Land. Here he finds that 2002 Gujrat riots killed over a thousand of people and also destroyed Pirbaag. Karsan recalls his childhood in 1960's India and the sequence of events ultimately led him to value intellect over faith. Karsan is the next in line after his father (Bapuji) to assume lordship of the shrine. He is unwilling to be "gaddi varas" because he longs to be just ordinary; to play cricket and be a part of the ordinary world. When his father prohibits him from joining a cricket coaching by a former cricketer R.D. Patel, he is deeply affected by the biblical story of Abraham preparing to sacrifice his son Issac to the Almighty. He compares himself with Issac and Bapuji with Abraham and cries in pain, The Saheb My Father? Was I a sacrifice? 5 He thinks that his father wants to scarify him for his traditional and spiritual obligations. Raja Singh, a truck driver always brings him news from the outer world. Mr David, his Christian teacher has a great impact on him during his younger days. Karsan becomes an agent of National Patriotic Youth Party on the consent of his father.

[4]

Karsan eventually lands a scholarship to Harvard University. He could not resist the opportunity to go finally the country of his aspirations. Despite his father's attempt to keep him close to the traditional ways, the excitement to establish his new existence in America proves more compelling. Karsan leaves his homeland and departs for Harvard University. But before his departure his father inherits him the holy words or bol of his forefathers. Karsan's time at Harvard proves delightful when he is surrounded by unlimited knowledge. He becomes so affected with new aspirations and knowledge that unwillingly he starts losing faith in traditionality and spirituality of Pirbaag shrine. For three decades Karsan lives freely without any filial and spiritual obligation. He becomes a professor in British Columbia, Marries with Marge Thompson and fathers a son and even changes his name I changed my name to Krishna Fazal, and I became the father of a boy, whom we named Julian. My Happiness was complete.6

Later we find that Karsans true happiness lies in fulfilling his spiritual calling when he decides to spread the fragrance of his shrine throughout the world by telling the story of Pirbaag. Unfortunately a tragedy strikes in his life when his only child Julian died in a road accident and his wife go away to leave him alone. One day, while reading his father's letters, he realizes that he has forged his identity and his heart craves for his native place. Eventually when he returns, Pirbaag is no longer standing, everything is destroyed and his brother converts himself into a rigid form of Islaam. Seeing this brutal violence Karsan is reminded of his role

[5]

I . . . must pick up the pieces of my trust and tell its story the duty of destroyers.7

At the insertion of knowledge and faith, Karsan learns acceptance and he keeps his tradition and ambition in balance. The story of The Assassin's Song, in a great historical sweep, takes the reader from a fictitious thirteen century village, Haripur in Gujrat to Harvard yard of the late 1960's, the British Columbia in 1980's and then back again to Gujrat communal riots. He shows how the riots have changed the lives of many; how the long tradition of communal harmony of the shrine has come to a halt. At individual level The Assassian's Song conspicuously depicts the in-betweenness of the protagonist Karsan Dargawalla. Karsan's inbetweenness underlies his entire life as he is pulled between tradition of faith and his own intellectual curiosity and adventurous spirit. He wants to lead a common mans life but his father keeps him reminding his position: No Karsan, think of who you are?

8

Karsan is caught between two

identities one is worldly; a cricket player who wants to pursue his career in cricket; an agent of National Patriotic youth party; an aspirant who goes to Harvard for higher education; a professor in a foreign land and a man with a changed name to forge his identity. Another identity is spiritual as he is a gaddi varas. But finally both the identities prove to be chimera for him as the communal riots have changed every thing. Even of the riots would not have taken place Karsan could not have chosen any stable identity. He is a typical product of postcolonial world though something of his family culture is deeply ingrained in his mind. Whereas his brother chooses to be a rigid Muslim, because of the impression of the Gujarat riots, it is impossible for Karsan to be purely one thing. He stands in a complex

[6]

relationship with history. He corroborates what Edward Said declares at the end of Culture and Imperialism (1994) No one today is purely one thing. Labels like Indian, or woman, or Muslim, or American are purely starting-points, which if followed into actual experience are quickly left behind. Imperialism consolidated the mixture of cultures and identities on a global scale. But its worst and most paradoxical gift was to allow people to believe that they were only, mainly, exclusively, white, or black, or Western, or Oriental. Yet just as human beings make their history, they also make their cultures and ethnic identities. No one can deny the persisting continuities of long traditions, sustained habitations, national languages, and cultural geographies, but there seems no reason except fear and prejudice to keep insisting on their separation and distinctiveness, as if that was all human life was about. Survival is, in fact, about the connections between things; in [T.S.] Eliot's phrase, reality cannot be deprived of the "other echoes [that] inhabit the garden."9

Karsan finally comes to undertake the reality that he can not dash the other echoes. He realizes that the attempts to resolve the mysteries of past is futile since past is never cut and dried and the in-betweenness is not just a product of the present but of history. His existence affirms the vital need for coexistence and understanding between individuals and peoples, in a world where to define oneself exclusively as "one thing" may lead to a disaster. Though

[7]

Karsan carries all the obligations from which he fled, he remembers the bol, picks up the thread of life which he has rejected three decades ago and does everything what his father once expected from him but he finds no redemption yet he arrives at a possible solution But here I stop to begin anew. For the call has come for me, again, and as Bapu-ji would say, this time I must bow.10

In this fictitious story, inspired by the Muslim mystics of medieval India, Vassanji explores a great tradition of communal harmony. He unravels a complex tradition of various beliefs and multiple affiliations; a tradition of great flux. Fundamentalism of any kind only damages such a great tradition. Karsan could have followed the same path which his brother has chosen. But his global experience, despite all the ambivalences, has inscribed a permanent impression of pluralism and tolerance on his mind which aspire him towards a greater form of humanity and spiritualism. Notes: 1. Robin Cohen tentatively describes diasporas as communities of people living together in one country who "acknowledge that "the old country" a notion often buried deep in language, religion, customer folklore-always has some claim on their loyalty and emotions". Robin Cohen, Global Diasporas: An Introduction, 1997 (London: Routledge, 2001), p. IX. 2. Indenture was the "contract by which the emigrant agreed to work for a given employer for five years, the emigrant was free

[8]

to re-indenture or to work elsewhere in colony; at the end of ten years he was entitled to a subsidized return passage". R.K. Jain, "Introduction: Overseas Emigration in the Nineteenth 1993), p. 4. The Indian indenture system started from the end of the African slavery in 1834 and continued until 1920. By then thousands of Indians were transported to various colonies of Europe to provide labour for sugar plantations. 3. The Mau Mau Uprising of 1952 to 1960 was an insurgency by Kenyan peasants against the British colonialist rule. The core of the resistance was formed by members of the Kikuyu ethnic group, along with smaller numbers of Embu and Meru. The uprising failed militarily, though it hastened Kenyan independence and motivated Africans in other countries to fight against colonial rule. It created a rift between the white colonial community in Kenya and the Home Office in London that set the stage for Kenyan independence in 1963. It is sometimes called the Mau Mau Rebellion or the Mau Mau Revolt, and, in official documents, the Kenya Emergency. The name Mau Mau for the rebel movement was not coined by the movement itself- they called themselves Muingi ("The Movement"), Muigwithania ("The Understanding"), Muma wa Uiguano ("The Oath of Unity") or simply "The KCA", after the Kikuyu Central Association that created the impetus for the insurgency. Veterans of the independence movement referred to themselves as the "Land and Freedom Army" in English. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mau_Mau_Uprising 4. Quotations from The Assassin's Song are from Indian edition (New Delhi: Penguin, 2007). Century", Indian Communities Abroad: Themes and Literature (New Delhi: Manohar Publication's,

[9]

5. 6. 7. 8. 9.

Ibid., p. 103. Ibid., p. 281. Ibid., p. 4. Ibid., p. 118. Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism 1993 (London: Vintage, 1994), p. 407. The T.S. Eliot quotation is from "Burnt Norton", the first poem in Four Quartets.

10.

The Assassin's Song, p. 368

References: 1. Cohen, Robin. Global Diasporas: An Introduction, 1997

(London: Routledge, 2001). 2. Jain, R.K. "Introduction: Overseas Emigration in the Nineteenth Century", Indian Communities Abroad: Themes and Literature (New Delhi: Manohar Publication's, 1993). 3. Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism1993 (London: Vintage, 1994) 4. Vassanji, M.G. The Gunny Sack (Canada: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1989) No New Land (Canada: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1991) The Book of Secrets Ltd.,1994) (Canada: McClelland and Stewart

[ 10 ]

Amriika (Canada: McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 1999) The In-Between World of Vikram Lall (Canada:

McClelland and Stewart Ltd., 2003) The Assassin's Song (New Delhi: Penguin, 2007)

Вам также может понравиться

- Null 11Документ126 страницNull 11Idrees BharatОценок пока нет

- Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo" by Zora Neale-Hurston | Conversation StartersОт EverandBarracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo" by Zora Neale-Hurston | Conversation StartersОценок пока нет

- Shamshone: Sun of Assyria: Five Generations of a Family from Iranian AzerbaijanОт EverandShamshone: Sun of Assyria: Five Generations of a Family from Iranian AzerbaijanОценок пока нет

- C 5Документ29 страницC 5ASHOKОценок пока нет

- The Soul of an Indian: And Other Writings from Ohiyesa (Charles Alexander Eastman)От EverandThe Soul of an Indian: And Other Writings from Ohiyesa (Charles Alexander Eastman)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (39)

- Bapsi Sidhwa: A Biographical SketchДокумент26 страницBapsi Sidhwa: A Biographical SketchAfia FaheemОценок пока нет

- Brown Boys and Rice Queens: Spellbinding Performance in the AsiasОт EverandBrown Boys and Rice Queens: Spellbinding Performance in the AsiasОценок пока нет

- Erna Brodber and Velma Pollard: Folklore and Culture in JamaicaОт EverandErna Brodber and Velma Pollard: Folklore and Culture in JamaicaОценок пока нет

- Moyez G. Vassanji - Contemporary AuthorsДокумент10 страницMoyez G. Vassanji - Contemporary Authorstvphile1314Оценок пока нет

- Chapter PageДокумент54 страницыChapter Pagezadak3199Оценок пока нет

- THE ICE CANDY MAN Jahanzeb Jahan IДокумент12 страницTHE ICE CANDY MAN Jahanzeb Jahan IKhushnood Ali0% (1)

- Beneath the Same Stars: A Novel of the 1862 U.S.-Dakota WarОт EverandBeneath the Same Stars: A Novel of the 1862 U.S.-Dakota WarОценок пока нет

- Research Journal of English Language and Literature: EmailДокумент4 страницыResearch Journal of English Language and Literature: EmailHayacinth EvansОценок пока нет

- The Girl Who Could Write and Unite: An Inspirational Tale about Gwendolyn BrooksОт EverandThe Girl Who Could Write and Unite: An Inspirational Tale about Gwendolyn BrooksОценок пока нет

- Bapsi Sidhwa As An South Asian NovelistДокумент4 страницыBapsi Sidhwa As An South Asian NovelistNoor Ul AinОценок пока нет

- Taslima Unbound: Writings on Feminism, Secularism, and Human RightsОт EverandTaslima Unbound: Writings on Feminism, Secularism, and Human RightsОценок пока нет

- Dramatic Movement of African American Women: The Intersections of Race, Gender, and ClassОт EverandDramatic Movement of African American Women: The Intersections of Race, Gender, and ClassОценок пока нет

- Colonial Mixed Blood: A Story of the Burghers of Sri LankaОт EverandColonial Mixed Blood: A Story of the Burghers of Sri LankaОценок пока нет

- The Sword of the Lord: The Roots of Fundamentalism in an American FamilyОт EverandThe Sword of the Lord: The Roots of Fundamentalism in an American FamilyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- Ravished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian Girl Who Lived Through the Great MassacresОт EverandRavished Armenia: The Story of Aurora Mardiganian, the Christian Girl Who Lived Through the Great MassacresОценок пока нет

- A Thousand Splendid Suns - 101 Amazingly True Facts You Didn't Know: 101BookFacts.comОт EverandA Thousand Splendid Suns - 101 Amazingly True Facts You Didn't Know: 101BookFacts.comРейтинг: 1 из 5 звезд1/5 (1)

- Mirabai Comes To AmericaДокумент24 страницыMirabai Comes To AmericaramanasriОценок пока нет

- Rebel Writers: The Accidental Feminists: Shelagh Delaney • Edna O’Brien • Lynne Reid Banks • Charlotte Bingham • Nell Dunn • Virginia Ironside • Margaret ForsterОт EverandRebel Writers: The Accidental Feminists: Shelagh Delaney • Edna O’Brien • Lynne Reid Banks • Charlotte Bingham • Nell Dunn • Virginia Ironside • Margaret ForsterРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Reconstructing History and Gender: Alice WalkerОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Reconstructing History and Gender: Alice WalkerОценок пока нет

- Women and Violence: Book ReviewsДокумент4 страницыWomen and Violence: Book ReviewsRAGHUBALAN DURAIRAJUОценок пока нет

- Women As Metaphor PDFДокумент7 страницWomen As Metaphor PDFUrvashi KaushalОценок пока нет

- Mam Amal ProjectДокумент12 страницMam Amal ProjectAns CheemaОценок пока нет

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Zora Neale Hurston: Stories and StorytellingОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Zora Neale Hurston: Stories and StorytellingОценок пока нет

- BCTG Guide-Inheritance of LossДокумент11 страницBCTG Guide-Inheritance of Losslalitv_27Оценок пока нет

- Looking for Jazz: A Memoir about the Black College and Southern Town That Changed My LifeОт EverandLooking for Jazz: A Memoir about the Black College and Southern Town That Changed My LifeОценок пока нет

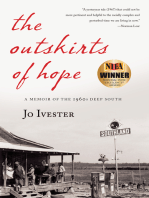

- The Outskirts of Hope: A Memoir of the 1960s Deep SouthОт EverandThe Outskirts of Hope: A Memoir of the 1960s Deep SouthРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)

- Accidental Sisters: Refugee Women Struggling Together for a New American DreamОт EverandAccidental Sisters: Refugee Women Struggling Together for a New American DreamОценок пока нет

- Diasporic Women in Jhumpa Lahiri's The Namesake: Indu. B. CДокумент4 страницыDiasporic Women in Jhumpa Lahiri's The Namesake: Indu. B. Cjesusdavid5781Оценок пока нет

- The Bush Devil Ate Sam: And Other Tales of a Peace Corps Volunteer in Liberia, West AfricaОт EverandThe Bush Devil Ate Sam: And Other Tales of a Peace Corps Volunteer in Liberia, West AfricaОценок пока нет

- Rereading AhilyaДокумент5 страницRereading AhilyaSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- UmaДокумент9 страницUmaSiddhartha Singh100% (2)

- Can The Subaltern Speak - SummaryДокумент5 страницCan The Subaltern Speak - Summarypackul100% (14)

- Notes On Raymond WilliamsДокумент5 страницNotes On Raymond WilliamsSiddhartha Singh75% (8)

- Narration and Discourse Critical Essays On Literature and Culture Review Article by Siddhartha SinghДокумент8 страницNarration and Discourse Critical Essays On Literature and Culture Review Article by Siddhartha SinghSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Walter Benjamin AnalysisДокумент8 страницWalter Benjamin AnalysisSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Communicating Configurations of KnowledgДокумент18 страницCommunicating Configurations of KnowledgSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Summary and Conclusion: HapterДокумент42 страницыSummary and Conclusion: HapterSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- The Natyashastra by Siddhartha SinghДокумент20 страницThe Natyashastra by Siddhartha SinghSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Performing Nautanki by Devendra SharmaДокумент250 страницPerforming Nautanki by Devendra SharmaSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- First Urdu Novel: Contesting Claims And Disclaimers: Haωan Sh≥HДокумент22 страницыFirst Urdu Novel: Contesting Claims And Disclaimers: Haωan Sh≥HSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Diasoric Conciousness..cmpltДокумент12 страницDiasoric Conciousness..cmpltSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Criticism and Theory by Siddhartha SinghДокумент11 страницCriticism and Theory by Siddhartha SinghSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Nautanki As A Performative Art Form of North IndiaДокумент8 страницNautanki As A Performative Art Form of North IndiaKriteshОценок пока нет

- STQ Issue 4 PDFДокумент119 страницSTQ Issue 4 PDFSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Siddhartha Singh On Romaticism For BA Sem II & MA Sem IДокумент11 страницSiddhartha Singh On Romaticism For BA Sem II & MA Sem ISiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Riders To The SeaДокумент11 страницRiders To The SeaSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Michel Foucault What Is An AuthorДокумент18 страницMichel Foucault What Is An AuthorSiddhartha Singh100% (1)

- University WitsДокумент6 страницUniversity WitsSiddhartha Singh100% (2)

- The Fly Katherine MansfieldДокумент5 страницThe Fly Katherine MansfieldSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- STQ Issue 4 PDFДокумент119 страницSTQ Issue 4 PDFSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Cultural Consciousness and Folk Elements in The Selected Plays of Habib Tanvir and Girish KarnadДокумент4 страницыCultural Consciousness and Folk Elements in The Selected Plays of Habib Tanvir and Girish KarnadSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Culture in The Plays of Girish Karnad: Dr. R. ChananaДокумент8 страницCulture in The Plays of Girish Karnad: Dr. R. ChananaSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- KeatsДокумент2 страницыKeatsSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- Lucy:Becomi Ngpost Humani NadayДокумент8 страницLucy:Becomi Ngpost Humani NadaySiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- File HandlerДокумент44 страницыFile HandlerImranОценок пока нет

- Ecosensitivity in Kalidasa's Abhigyan Shakuntala: Research Scholar, Dept. of English, Patna UniversityДокумент12 страницEcosensitivity in Kalidasa's Abhigyan Shakuntala: Research Scholar, Dept. of English, Patna UniversitySiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses": Exposition and InterpretationДокумент16 страниц"Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses": Exposition and InterpretationSiddhartha Singh100% (1)

- Travel Writing Seth and Ghosh RevisedДокумент12 страницTravel Writing Seth and Ghosh RevisedSiddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- What Is The Sapir Whorf Hypothesis?: American Anthropologist March 1984Документ16 страницWhat Is The Sapir Whorf Hypothesis?: American Anthropologist March 1984Siddhartha SinghОценок пока нет

- (Soc Stud 1) EssayДокумент1 страница(Soc Stud 1) Essayrudolph benito100% (5)

- E Tech DLL Week 7Документ3 страницыE Tech DLL Week 7Sherwin Santos100% (1)

- McCann Truth Central Final Truth About Fans Executive Summary InternalДокумент60 страницMcCann Truth Central Final Truth About Fans Executive Summary Internalsantosheg100% (1)

- Voices of Early Modern JapanДокумент306 страницVoices of Early Modern JapanAnonymous 1MoCAsR3100% (5)

- Script JsДокумент3 страницыScript JseugenemenorcaОценок пока нет

- Grade 10 Mock PCUPДокумент3 страницыGrade 10 Mock PCUPNishka NananiОценок пока нет

- Theme Essay Rubric ForДокумент1 страницаTheme Essay Rubric Forapi-233955889Оценок пока нет

- Fundamental RightsДокумент272 страницыFundamental RightsparaskevopОценок пока нет

- Lesson 7Документ4 страницыLesson 7api-249904851Оценок пока нет

- Results and DiscussionДокумент9 страницResults and DiscussionCristine ChescakeОценок пока нет

- Lakota WomanДокумент3 страницыLakota WomanChara100% (1)

- Kolb Learning StylesДокумент11 страницKolb Learning Stylesbalu100167% (3)

- Bsam 2019 Q2-Sagunt Bonsai School-V1Документ6 страницBsam 2019 Q2-Sagunt Bonsai School-V1MarcialYusteBlascoОценок пока нет

- Information On India: ZoroastrianismДокумент4 страницыInformation On India: ZoroastrianismNikita FernandesОценок пока нет

- Cross-Cultural ConsumptionДокумент6 страницCross-Cultural Consumptionojasvi gulyaniОценок пока нет

- Social PsycologyДокумент18 страницSocial PsycologyJohn WalkerОценок пока нет

- Telephone ConversationДокумент4 страницыTelephone ConversationAnshuman Tagore100% (2)

- (Philosophy and Medicine 82) Josef Seifert (Auth.) - The Philosophical Diseases of Medicine and Their Cure - Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine, Vol. 1 - Foundations (2004, Springer Netherlands)Документ434 страницы(Philosophy and Medicine 82) Josef Seifert (Auth.) - The Philosophical Diseases of Medicine and Their Cure - Philosophy and Ethics of Medicine, Vol. 1 - Foundations (2004, Springer Netherlands)Edson GilОценок пока нет

- How To Meet ClientДокумент5 страницHow To Meet ClientDevano PakpahanОценок пока нет

- School ReportДокумент2 страницыSchool ReportVivian HipolitoОценок пока нет

- English Enhancement For Specific Profession-LinguisticsДокумент2 страницыEnglish Enhancement For Specific Profession-LinguisticsBRILLIANT AGACID HEQUILANОценок пока нет

- Tips - The Warrant Chiefs Indirect Rule in Southeastern N PDFДокумент350 страницTips - The Warrant Chiefs Indirect Rule in Southeastern N PDFISAAC CHUKSОценок пока нет

- Name: Charose A. Manguira Co-Teaching: Strengthening The CollaborationДокумент4 страницыName: Charose A. Manguira Co-Teaching: Strengthening The CollaborationDennisОценок пока нет

- (L) Emile Durkheim - Value Judgments and Judgments of Reality (1911)Документ14 страниц(L) Emile Durkheim - Value Judgments and Judgments of Reality (1911)Anonymous fDM11L6i100% (1)

- CrimRev Garcia Notes Book 2Документ153 страницыCrimRev Garcia Notes Book 2dОценок пока нет

- Semantic Features in Daily CommunicationДокумент2 страницыSemantic Features in Daily CommunicationVy Nguyễn Ngọc HuyềnОценок пока нет

- Internship ReportДокумент32 страницыInternship ReportMinawОценок пока нет

- Rousseau A Guide For The Perplexed Guides For The PerplexedДокумент157 страницRousseau A Guide For The Perplexed Guides For The PerplexedMarcelo Sevaybricker100% (4)

- Badiou' DeleuzeДокумент204 страницыBadiou' DeleuzeBeichen Yang100% (1)

- Kenneth Reek - Pointers On CДокумент4 страницыKenneth Reek - Pointers On ClukerlioОценок пока нет