Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Use of Interactive Theater For Faculty Development in Multicultural Medical Education

Загружено:

Jeffrey SteigerОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Use of Interactive Theater For Faculty Development in Multicultural Medical Education

Загружено:

Jeffrey SteigerАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

2007; 29: 335340

Use of interactive theater for faculty development in multicultural medical education

ARNO K. KUMAGAI, CASEY B. WHITE, PAULA T. ROSS, JOEL A. PURKISS, CHRISTOPHER M. ONEAL & JEFFREY A. STEIGER

University of Michigan, USA

Abstract

Background: The development of critical consciousness, anchored in principles of social justice, is an essential component of medical education. Aim: In order to assist faculty instructors in facilitating small-group discussions on potentially contentious issues involving race, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic class, a faculty development workshop was created. Methods: The workshop used Forum Theater techniques in which the audience was directly involved in determining the course of a simulated classroom discussion and conflict. We assessed the workshops impact on the instructors attitudes regarding facilitation of small-group discussions through two surveys: one to gauge immediate impressions, and another, 915 months later, to assess impact over time. Results: Immediately after the workshop, participants reported that the topics covered in the sketch and in the discussion were highly relevant. In the follow-up survey, the instructors agreed that the workshop had raised their awareness of the classroom experiences of minorities and women and had offered strategies for addressing destructive classroom dynamics. 72% reported that the workshop led to changes in their behavior as facilitators. Differences in responses according to gender were observed. Conclusions: A workshop using interactive theater was effective in training faculty to facilitate small-group discussions about multicultural issues. This approach emphasizes and models the need to foster critical consciousness in medical education.

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by George Washington University on 04/25/11 For personal use only.

Introduction

As a nation, we are aware of the need for physicians to provide care to all patients in an increasingly diverse society (Cohen 1997; Liaison Committee on Medical Education 2004). Medical schools have responded to this need with a variety of modules to help their students achieve these skills; however, many approaches have been criticized for narrowly and superficially equating cultural competency with a series of specific behaviors that can be observed and then checked on a list as done (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia 1998; Dogra & Karnik 2003; Taylor 2003; Wear 2003). We believe that preparing students to provide care to a diverse society requires more than the acquisition of a knowledge base in the biomedical sciences and the development of clinical and critical-thinking skills. Our goals include helping students to develop the critical consciousness that underlies true understanding of the complex issues comprising cultural competence. We conceptualize critical consciousness as involving reflection, engaged discussion, examination of personal assumptions and biases and of societal inequities, and accepting personal responsibility for finding and enacting solutions (Freire 1993; Burbules & Berk 1999). This largely falls within the affective domain of learning outcomes. Pedagogy that achieves these outcomes must include engagement of diverse views in a safe and interactive environment (Hurtado 2001; Gurin et al. 2004). Our approach

Practice points

. The development of critical consciousness is an essential part of medical education. . Critical consciousness with respect to issues of diversity may be enhanced through small-group discussions in a safe, supportive environment. . Faculty instructors require training to effectively facilitate such discussions. . Interactive theater may assist instructors in understanding and deconstructing negative small-group dynamics and collaboratively working towards solutions.

consists of carefully crafted small-group discussions focused on ethical and social issues in healthcare. Exchanges are stimulated by creating a cognitive and affective disequilibrium, in which learners are challenged with unfamiliar, and at times uncomfortable, situations, ideas, and perspectives (Piaget 1985; Freire 1993; Gurin et al. 2004). Thus, the faculty facilitators role in this setting is keyit is not to avoid controversy and conflict, but to raise contradictions and questions as a way of encouraging reflection and discussion (Freire 1993). Discussions about multicultural issues have been shown to have positive effects on a variety of skills and characteristics that are important in clinical practice,

Correspondence: Arno K. Kumagai, 3901 Learning Resource Center #0726, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0726, USA. Tel: 734 615 4886; fax: 734 936 2236; email: akumagai@umich.edu

ISSN 0142159X print/ISSN 1466187X online/07/0403356 2007 Informa UK Ltd. DOI: 10.1080/01421590701378662

335

A. K. Kumagai et al.

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by George Washington University on 04/25/11 For personal use only.

including leadership, critical thinking, and perspective-taking (Gurin et al. 2004; Hurtado 2005). Such discussions, however, are not without risks. Potential problems include imposition of the facilitators perspectives on the group, avoidance of conflict surrounding issues of race, undermining of discussions by those hostile toward diversity, and heated debates that degenerate into personal arguments. Any of these conditions can stifle dialogue or isolate the very students whose voices must be heard in these discussions (e.g. women, gay and lesbian students, students of color) (Tatum 1992; Chesler et al. 1993; Goodman 1995; Chan & Treacy 1996; Wolfe & Spencer 1996; Dogra & Karnik 2003; Hurtado 2005). To prepare our instructors for the task of facilitating smallgroup discussions related to diversity and social justice, we collaborated with the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT) at our institution to design an interactive faculty workshop. The CRLT Players use Forum Theater techniques to raise awareness of the problems faced by faculty and students in discussions of diversity, and to explore effective classroom methods for addressing them (Bollag 2005). In addition to extensive training in acting, the CRLT Players undergo training to understand their own and each others perspectives, assumptions, and hidden biases with respect to issues of race, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic class (Bollag 2005). The specific goals for the faculty development workshop were as follows: (1) to enhance faculty understanding of emotional issues that can arise in discussions involving complex social topics with attitudinal learning outcomes; (2) to increase awareness of how diverse groups of students experience, react to, and interact during such discussions; (3) to provide strategies to address destructive group dynamics and foster a productive climate and discussion; and (4) to help faculty feel comfortable with and capable of facilitating these discussions. We hypothesized that interactive theater was an effective method for helping our facilitators achieve these goals.

Methods

Our curriculum, revised in 2003, includes longitudinal cases in the first and second years of the 4-year medical-school curriculum, as well as reappraisals of the goals and issues raised in the cases after the students have had clinical exposure in their third-year clerkships. The longitudinal cases are robust, paper-based patient cases that connect basic science principles with patients and present increasingly complexand at times controversial psychosocial and ethical issues for examination, reflection, and discussion. The cases are discussed in 15 small groups of 1012 students, with one faculty facilitator per group. In order to establish a safe, familiar environment in which to hold engaged, potentially contentious discussions, the small-group membership and faculty instructor remain unchanged for the first, second, and third years. There is extensive faculty development, including at least two workshops each year, quarterly faculty meetings, and feedback to individual faculty facilitators by the Course 336

Director, Associate Director or Assistant Dean for Medical Education, following observation of small-group sessions. In the workshops, faculty instructors are trained to facilitate student discussions (i.e. not to lecture), and are encouraged not to avoid the controversies or conflicts central to discussions on race, gender, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic class. Rather, the faculty instructors are expected to assure a safe and respectful environment for everyone in the group, and to raise questions, identify contradictions, and stimulate discussion that encourages individual and shared reflection of these issues and their consequences (Freire 1993). Topics covered in faculty development workshops include active-learning methods, developmental models of adult learning, facilitating smallgroup discussions, group problem-solving of challenges in small-group facilitation, and providing students with feedback and evaluations. This study surveyed the faculty instructors opinions about the value and longer-term effects of a workshop, to prepare them for facilitating discussions of multicultural issues in healthcare. Two faculty development workshops of 3.5 hours each were held for facilitators in September 2004 and January 2005 (two dates were offered to ensure every facilitator attended a workshop). Approximately 15 faculty members participated in each workshop, which was moderated by the Course Director (the first author) and featured an activity with the CRLT Players theater group. The CRLT Players used an adapted version of Forum Theater to engage facilitators in a discussion of small-group dynamics. Forum Theater was originally derived from the Theater of the Oppressed by Boal (1979), in which the traditional barrier between the actors and the audience is broken down, and the audience becomes directly involved in determining the course of the play. This approach is rooted in Freires (1993) work on adult learning, and emphasizes the development of critical consciousness (conscientizac ao) in the adult learner. The scenario used by the CRLT Players was based on an actual discussion that had taken place in one of the longitudinal-case groups the previous year. The discussion of an issue related to a patients preference for a physician of a specific race and culture had devolved into a very personal argument between two students, ultimately marginalizing and silencing everyone else in the group. In the CRLT Players adaptation, a 10-minute sketch of the classroom discussion was performed. The CRLT Players were staged as a longitudinal-case group with a faculty facilitator. Immediately after playing out the discussion and argument, the actors remained in role and the faculty audience was given the opportunity to ask each student and the facilitator about his or her thoughts or feelings during the discussion and ensuing argument. Then the faculty engaged in a problem-solving group session, during which they reflected on their impressions of the students and facilitators comments, their own personal and professional experiences, identified the contentious, emotional issues that had created the situation, and then explored alternate strategies for facilitating the discussion in a more constructive manner. After a 15-minute discussion, the sketch was re-enacted with the audiences suggestions incorporated (Boal 1979).

Interactive theater in multicultural medical education

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by George Washington University on 04/25/11 For personal use only.

The evaluation of the workshops value, completed by all participants immediately after the workshop, consisted of six Likert-type questions regarding the value of the workshop and the interactive sketch in understanding aspects of multicultural medical education. In addition, to allow faculty time to assimilate what they had learned into their facilitation of small-group discussions, an online evaluation of the workshops long-term effects on their teaching and facilitating was sent to the faculty in March 2005 (915 months after the workshop, depending on which workshop they participated in). The survey comprised six Likert-scale questions that asked respondents to indicate their agreement on a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The questions focused on the impact of the workshop on respondents awareness of the issues and of the dynamics within their groups, and whether they had learned new strategies for facilitating discussion. A yesno type question asked whether the workshop led to changes in their behavior as facilitators. Statistical analysis involved computation of summary statistics (means and standard deviations) to gauge the respondents perceptions of the experience. We also generated a series of independent-sample t-tests to determine if statistically significant differences existed in responses when analyzed by gender (results at the p < 0.05 level were considered significant). Within a week of completion of the survey, respondents were invited to a focus group, facilitated by an educational expert not associated with the workshop, to explore more in-depth the impact of the workshop. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board of the university.

Results

With the exception of one item, the survey assessing the value of the workshop was completed by all the 29 faculty facilitators

who participated in the workshop (Table 1). The respondents were diverse in gender (13 men and 16 women) and race/ ethnicity (3 African American, 19 White, 4 Asian Pacific Islanders, 2 Latina/Hispanic, 1 Arab American). And with the exception of one item, the follow-up survey assessing the effects of the workshop was completed by 19 of the 29 faculty who participated in the workshop (8 women, 11 men; 3 African American, 11 White, 4 Asian Pacific Islander, 1 Arab American) (Table 2). Results from the first survey, which assessed the value of the workshop, are summarized in Table 1. In general, the relevance of topics covered in the sketch and the interactive discussion was rated highly, with means of 4.69 0.54 and 4.59 0.63, respectively. Similarly, the faculty felt that the balance between information transmitted and interactive discussion was appropriate (mean ranking of 4.41 0.63), and that the interactive discussion enhanced their understanding of the issues (mean ranking of 4.24 0.79). In comparison, their ranking of whether the skit reflected their own experiences was lower (mean 3.90 0.67), as was the usefulness of the printed materials (mean 3.93 0.88). Comments from the faculty revealed that the score for the latter was low because many had not had a chance to read the printed materials before the evaluation. Results from the second survey, which assessed the longterm effects of the workshop, are summarized in Table 2. There was strong agreement that the workshop had led the facilitators to reflect on how their actions in the classroom affected their students (mean ranking 4.32 0.48), and general agreement that they had learned strategies for addressing the classroom dynamics that can negatively impact some students (mean ranking 3.95) and that it had raised their awareness of the classroom experiences of minorities and women (mean ranking 3.95 0.69). Respondents also agreed that the

Table 1. Ratings of workshop value. Total Item (grand mean)

The issues/topics raised in the actors performance of the sketch . . . a The issues/topics raised in the audiences/actor interactive discussion about the sketch . . . a The audience/actor interactive discussion(s) enhanced my understanding of the issues.b The balance between giving information and encouraging discussion was appropriate.b The issues raised in the performance reflected my personal experience.b Printed materials provided . . . a (Grand mean of 5-point-scale item responses)

Male n

29

Female 95% CI 2-tail p-value

0.982

Mean

4.69

SD

0.541

Mean

4.69

SD

0.630

n

13

Mean

4.69

SD

0.479

n

16

for difference

0.418 0.427

4.59

0.628

29

4.62

0.506

13

4.56

0.727

16

0.436

0.542

0.826

4.24

0.785

29

4.38

0.650

13

4.13

0.885

16

0.345

0.864

0.386

4.41

0.628

29

4.38

0.506

13

4.44

0.727

16

0.542

0.436

0.826

3.90

0.673

29

4.00

0.708

13

3.81

0.655

16

0.332

0.707

0.466

3.93 4.33

0.884 0.454

15 29

4.00 4.37

1.155 0.470

7 13

3.88 4.30

0.641 0.455

8 16

0.898 0.282

1.148 0.425

0.796 0.682

Overall mean scores for questionnaire items are based on a 5-point Likert scale, in which a higher score indicates a more positive evaluation. T-tests were performed for differences in group means; a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. aScale: 1 not very useful to 5 very useful. bScale: 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree.

337

A. K. Kumagai et al.

Table 2. Ratings of workshop effects.. Total Item (mean)

Made me more aware of the classroom experiences of women and minority students.a Made me consider this a more important issue than I did before.a Led me to reflect on how my actions in the classroom affect students.a Made me more proactive about creating a positive classroom climate.a Made me feel more comfortable facilitating discussions involving multicultural issues.a Gave me strategies to address classroom dynamics that negatively impact women and minority students.a (Grand mean of 5-point-scale item responses) Did attendance at the CRLT Theatre Performance lead to changes in your behavior?b

Male n

19

Female 95% CI 2-tail p-value

0.007

Mean

3.84

SD

0.688

Mean

4.18

SD

0.603

n

11

Mean

3.38

SD

0.518

n

8

for difference

0.249 1.365

3.32

0.749

19

3.55

0.820

11

3.00

0.535

0.112

1.203

0.098

4.32

0.478

19

4.45

0.522

11

4.13

0.354

0.095

0.754

0.120

3.89

0.658

19

4.09

0.701

11

3.63

0.518

0.153

1.085

0.131

3.58

0.692

19

3.73

0.786

11

3.38

0.518

0.323

1.027

0.286

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by George Washington University on 04/25/11 For personal use only.

3.95

0.780

19

4.00

0.894

11

3.88

0.641

0.659

0.909

0.741

3.82

0.500

19

4.00

0.587

11

3.56

0.153

0.034

0.841

0.036

0.72

0.461

18

0.73

0.467

11

0.71

0.488

0.474

0.500

0.956

Overall mean scores for questionnaire items are based on a 5-point Likert scale where higher scores indicate a more positive evaluation. T-tests were performed for differences in group means; a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. aScale: 1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree. bMeans indicate proportion of yes responses to no responses (scale: 1 yes, 0 no)

workshop made them more proactive in creating a positive classroom climate (mean ranking 3.89 0.66). There was less agreement that the workshop influenced their comfort in facilitating discussions involving multicultural issues (mean ranking 3.58 0.69). Given that some of the more controversial topics and discussions are rooted in issues related to race and gender, we also explored these differences in the facilitators evaluations. However, the minority group was too heterogeneous, and the subgroup numbers too small, for us to draw meaningful conclusions. We did, however, compare the rankings by men with the rankings by women. Men tended to rate the value of the workshop slightly more favorably than women across almost all areas surveyed (Table 1), and, accordingly, they rated the effects of the workshop more favorably than women did, across all items (grand mean difference 0.44, t 2.37, df 11.80, p 0.036; Table 2). This difference in effects achieved significance on one particular item, The workshop made me more aware of the experience of women and minority students (mean difference 0.80, t 3.05, df 17, p 0.007). Overall, 73% of the 11 men and 71% of the 7 women reported that the workshop had led to changes in their behavior. In the focus groups, faculty reported that the workshop made them more sensitive to the cultural aspects of our discussions and made them aware that they should pay more attention to nonverbal cues in their groups. Several facilitators felt that the opportunity to work through a difficult situation with colleagues was valuable: [it] gave you a notion about how you would approach a situation like thathearing 338

what works and what doesnt work and what your colleagues say about that youll approach these things with more confidence.

Discussion

Medical schools are devoting substantial effort to training students to provide effective healthcare to a diverse society. It is our belief that medical training must articulate outcomes that involve not only acquisition of knowledge and skills, but also attitudes that include the development of critical consciousness and a commitment to finding solutions to societal problems. We contend that controversy and even conflict are, at times, a necessary part of this process, and that an engaged, reflective, honest exploration of these issues is the whetstone against which critical consciousness is sharpened. We agree with colleagues who have reported on the need for an emphasis on students and healthcare providers attitudes as they relate to providing sensitive and responsible medical care to all patients (Beagan 2003). We also agree with educators who stress the importance of considering differences in power in the relationships between patients and care providers (Beagan 2003; Wear 2003) and of designing educational activities that foster the understanding and practice of selfawareness and self-assessment skills in the context of these complex issues (Novack et al. 1999). The changes that we have made to undergraduate medical education at our institution reflect our belief in the need for a curriculum that helps students to learn how to listen openly and without judgment, and to explore their own biases and beliefs, as well as the influence

Interactive theater in multicultural medical education

these biases and assumptions have on their interactions with others. Education in this context is aimed at producing physicians who are capable of, and committed to, addressing societal problems and seeking solutions. This perspective, in a very real sense, lies at the core of critical consciousness and its application in medical education. This task is, of course, easier said than done on an educational level. Given the obstacles and risks inherent in discussions of diversity and disparities in healthcare, numerous recommendations have been proposed that aim to encourage discussion, address resistance, and create safe environments for the exchange of ideas (Tatum 1992; Chesler et al. 1993; Goodman 1995; Chan & Treacy 1996). However, it is critical that faculty instructors are trained to facilitate these exchanges effectively, so that learning outcomes can be achieved. In our program, we have designed a faculty-development activity that incorporates interactive theater techniques, as well as collaborative group learning and problem-solving, to help faculty meet these objectives. Roleplay and simulation have been used as learning techniques in a variety of settings in medical education (Mann et al. 1996; Jones 2001; Benbassat & Baumal 2002; Heru 2003). Interactive theater differs from these approaches in several respects. Unlike traditional roleplay, the actors in CRLT theater program undergo extensive training in smallgroup interactions involving race, gender, sexual orientation, and class, and incorporate this training into their performance and their interactions with the audience (Bollag 2005). Furthermore, by freezing the action and engaging the audience in discussion with the students and instructor, interactive theater can also help faculty to deconstruct smallgroup dynamics that may marginalize women or students of color, for example, and threaten the safety of the group or the effectiveness of the discussion. This activity consequently encourages instructors to reflect on their own approaches to teaching and learning and to work collaboratively to solve challenges that arise in small-group teaching. Just as importantly, this approach models the very type of exchanges and problem-solving activities that the facilitators are expected to use in their small-group discussions with students. Finally, the sketch and discussion encourage instructors to review their own perspectives, assumptions, and biases in the same way we work to help students achieve attitudinal learning outcomes. Attitudes towards teachingas well as learningare influenced by the different identities, backgrounds, and perspectives that instructors bring into the classroom (Harlow 2003; Hurtado 2005; Norton et al. 2005). We were, therefore, interested in analyzing the responses to the surveys with respect to the self-identified gender of the instructors. When compared with women in our sample, the men offered a consistently more positive evaluation of the effectiveness of the interactive theater experience for all of the survey items, and the difference achieved statistical significance for one item (Table 2). We had anticipated the differences we saw between the men and women. We had hypothesized that working in a demanding and culturally entrenched discipline and environment had probably pre-sensitized female faculty members to issues similar to those under discussion in the small groups,

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by George Washington University on 04/25/11 For personal use only.

including marginalization, disparate treatment, stereotyping, and bias. In fact, in a study in which medical students were interviewed during their clinical years about institutional culture, they reported seeing practices every day that reinforced gender inequities in medicine (Beagan 2003). Nonetheless, the lack of statistically significant differences between male and female instructors, which might reflect the overall small number of respondents, is a limitation of the study. A maximum of 30 instructors were eligible to participate in the workshops and, therefore, the power of the two surveys to detect gender-related differences in response was limited by the very nature of the teaching activity and course design. In summary, our motivation in undertaking this project was our belief that attitudinal outcomes, including the development of critical consciousness, are essential in preparing medical students to care for members of a diverse society and to work with medically underserved populations. Although we describe the use of a specific technique interactive theaterto train faculty instructors to facilitate discussions on diversity, several points raised in this discussion may be applied to multicultural teaching in general. First, the workshop emphasizes the importance of faculty development in acquiring necessary skills to facilitate small-group discussions in multicultural education. Second, this approach demonstrates a type of activity that allows interactive deconstruction and critical reflection on teaching and smallgroup dynamics among instructorsprocesses that may lead to more thoughtful facilitation of discussions on contentious topics. Third, this activity also models a pedagogic method that incorporates the creation of a cognitive disequilibriumthat is, self-reflection stimulated by encountering unfamiliar values, perspectives, experiences or beliefs (Piaget 1985)as an tool in enhancing discussions of psychosocial topics in medicine. While use of interactive theater per se might not be possible at many institutions, the findings in the present study suggest that educational experiences for students and faculty that include these general approaches are effective in facilitating productive discussions and achieving intended learning outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Eric Dey for advice regarding statistical analysis and Dr Monica Lypson and Dr Joseph C. Fantone for many helpful discussions. We would also like to thank the longitudinal case small-group instructors and students for their commitment and efforts to teaching and learning.

Notes on contributors

ARNO K. KUMAGAI, MD, is Director of the Longitudinal Case Studies courses, at the University of Michigan Medical School. CASEY B. WHITE, PhD, is Assistant Dean for Medical Education, the University of Michigan Medical School. PAULA T. ROSS, MA, is Research Project Manager in the Office of Medical Education, at the University of Michigan Medical School. JOEL A. PURKISS, PhD, is the Associate Director for Curricular Evaluation in the Office of Medical Education, at the University of Michigan Medical School.

339

A. K. Kumagai et al.

CHRISTOPHER M. ONEAL, PhD, is Senior Coordinator Consultant for Institutional Initiatives, Centre for Research in Learning and Teaching at the University of Michigan. JEFFREY STEIGER, BA, is Director of the CRLT Theater Program at the University of Michigan.

References

Beagan BL. 2003. Teaching social and cultural awareness to medical students: Its all very nice to talk about it in theory, but ultimately it makes no difference. Acad Med 78:605614. Benbassat J, Baumal R. 2002. A step-wise role playing approach for teaching patient counseling skills to medical students. Patient Educ Counsel 46:147152. Boal A. 1979. Theater of the oppressed (London, Pluto). Bollag B. 2005. Classroom drama: A University of Michigan program uses theater to teach professors sensitivity to women and minority groups. Chron High Educ 51:A12A14. Burbules NC, Berk R. 1999. Critical thinking and critical pedagogy: Relations, differences, and limits, in: TS Popkewitz & L Fendler (Eds), Critical Theories in Education: Changing Terrains of Knowledge and Politics, pp. 4565 (New York, Routlege). Chan CS, Treacy MJ. 1996. Resistance in multicultural courses: Student, faculty, and classroom dynamics. Am Behav Sci 40:212221. Chesler MA, Wilson M, Malani A. 1993. Perceptions of faculty by students of color. Mich J Pol Sci 16:5479. Cohen JJ. 1997. Finishing the bridge to diversity. Acad Med 72:103109. Dogra N, Karnik N. 2003. First-year medical students attitudes toward diversity and its teaching: an investigation at one U.S. Medical School. Acad Med 78:11911200. Freire P. 1993. Pedagogy of the oppressed (New York, Continuum). Goodman DJ. 1995. Difficult dialogues. Enhancing discussions about diversity. Coll Teach 43:4752. Gurin P, Nagda BA, Lopez GE. 2004. The benefits of diversity in education for democratic citizenship. J Soc Iss 60:1734. Harlow R. 2003. Race doesnt matter, but . . .: The effect of race on professors experiences and emotion management in the undergraduate college classroom. Race Racism Discrim 66:348363.

Med Teach Downloaded from informahealthcare.com by George Washington University on 04/25/11 For personal use only.

Heru AM. 2003. Using role playing to increase residents awareness of medical student mistreatment. Acad Med 78:3538. Hurtado S. 2001. Linking diversity and educational purpose: How diversity affects the classroom environment and student development, in: G Orfield & M Kurlaender (Eds), Diversity Challenged: Evidence on the Impact of Affirmative Action, pp. 187203 (Boston, Harvard Education Publishing Group). Hurtado S. 2005. The next generation of diversity and intergroup relations research. J Soc Iss 61:595. Jones C. 2001. Sociodrama: A teaching method for expanding the understanding of clinical issues. J Palliat Med 4:386390. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. (2004). Function and structure of a medical school. Available at http://www.lcme.org/pubs.htm newschools (accessed 14 June 2007). Mann BD, Sachdeva AK, Nieman LZ, Nielan BA, Rovito MA, Damsker JI. 1996. Teaching medical students by role playing: A model for integrating psychosocial issues with disease management. J Cancer Educ 11:6572. Norton L, Richardson TE, Hartley J, Newstead S, Mayes J. 2005. Teachers beliefs and intentions concerning teaching in higher education. High Educ 50:537. Novack DH, Epstein RM, Paulsen RH. 1999. Toward creating physicianhealers: Fostering medical students self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being. Acad Med 74:516520. Piaget J. 1985. The equilibration of cognitive structures: the central problem of intellectual development (Chicago, University of Chicago Press). Tatum BD. 1992. Talking about race, learning about racism: The application of racial identity development theory in the classroom. Harvard Educ Rev 62:124. Taylor JS. 2003. Confronting culture in medicines culture of no culture. Acad Med 78:555559. Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. 1998. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved 9:117125. Wear D. 2003. Insurgent multiculturalism: Rethinking how and why we teach culture in medical education. Acad Med 78:549554. Wolfe CT, Spencer SJ. 1996. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their overt and subtle influence in the classroom. Am Behav Sci 40:176185.

340

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Nolei Belarmino CVДокумент2 страницыNolei Belarmino CVti noleiОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- LL Dece Standards Fulldraft9Документ370 страницLL Dece Standards Fulldraft9api-523534173Оценок пока нет

- Observation Sheet FsДокумент2 страницыObservation Sheet FsDolly ManaloОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- JH JW Leveled Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыJH JW Leveled Lesson Planapi-314361473Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- EMasters Student HandbookДокумент48 страницEMasters Student Handbookharikevadiya4Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Capstone Project ModuleДокумент12 страницCapstone Project ModuleJeffrey MasicapОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Day 1Документ16 страницDay 1Rehan HabibОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- GR 5 Term 4 2017 Maths TrackerДокумент108 страницGR 5 Term 4 2017 Maths TrackerIrfaanОценок пока нет

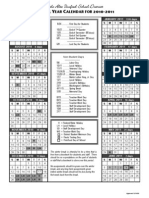

- PAUSD SchoolYearCalendar2010Документ1 страницаPAUSD SchoolYearCalendar2010Justin HolmgrenОценок пока нет

- 10 đề ôn luyện Tiếng Anh học kì I lớp 12Документ46 страниц10 đề ôn luyện Tiếng Anh học kì I lớp 12NguyenNgocОценок пока нет

- B Tech Results - CompressedДокумент2 страницыB Tech Results - CompressedRajnikant YadavОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Barclays Life Skills (F2F) JOB READINESS WORKSHOPДокумент2 страницыBarclays Life Skills (F2F) JOB READINESS WORKSHOPviraaj mehraОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- 5e Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницы5e Lesson Planapi-354775391Оценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Assessment/ Checking of Outputs: H7GD-Ib-13Документ1 страницаAssessment/ Checking of Outputs: H7GD-Ib-13Raymund MativoОценок пока нет

- 39th IATLIS National Conference 2023Документ3 страницы39th IATLIS National Conference 2023Sukhdev SinghОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Allied School System Internship ReportДокумент64 страницыAllied School System Internship Reportbbaahmad8963% (30)

- Standard Six Reading Program RationaleДокумент1 страницаStandard Six Reading Program Rationaleapi-278580587Оценок пока нет

- What Makes Continuing Education Effective PerspectДокумент6 страницWhat Makes Continuing Education Effective PerspecttestОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Postgraduate - 17 January 2023Документ2 страницыPostgraduate - 17 January 2023Times MediaОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Maths XiДокумент2 страницыMaths Xizy6136Оценок пока нет

- Special Education: Masters & Licensure ProgramsДокумент12 страницSpecial Education: Masters & Licensure Programsmgentry1Оценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- For University Stuttgart: Copies of QualificationsДокумент2 страницыFor University Stuttgart: Copies of QualificationsMJ GaleanoОценок пока нет

- Traditional vs. Online EducationДокумент5 страницTraditional vs. Online EducationEdilbert Bonifacio GayoОценок пока нет

- FRIT 7234 Ethical Use of Information Embedded LessonДокумент9 страницFRIT 7234 Ethical Use of Information Embedded LessonMunoОценок пока нет

- Senses Lesson PlanДокумент3 страницыSenses Lesson Planapi-134634747Оценок пока нет

- CNF DLL Week 5 q2Документ5 страницCNF DLL Week 5 q2Bethel MedalleОценок пока нет

- Don Marcos Rosales Elementary School Ipcrf-Development Plan: Department of EducationДокумент2 страницыDon Marcos Rosales Elementary School Ipcrf-Development Plan: Department of Educationmarilene figaresОценок пока нет

- Scholarship and Trainings For Filipino TeachersДокумент26 страницScholarship and Trainings For Filipino Teacherschoi_salazarОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Sri Kumaran Children's Home - NurseryДокумент2 страницыSri Kumaran Children's Home - NurseryKrishna PrasadОценок пока нет

- Adapted From Ginger Tucker's First Year Teacher NotebookДокумент3 страницыAdapted From Ginger Tucker's First Year Teacher Notebookapi-349880083Оценок пока нет