Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Books

Загружено:

parminder211985Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Books

Загружено:

parminder211985Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

MUNDAVANI

By Giani Gurdit Singh Published by Sahitya Prakashan, 56, Sector 4, Chandigarh Pages: 302, Price: US $ 15.00 10.00 A Review by P.S. Bawa*

* I.P.S. (Retd.) Email: P_S_Bawa@yahoo.co.in @ The book has been, at the time of first edition, reviewed by the renowned scholar of the Sikh Lore, Dr. I.J. Singh of New York University, vide SR: April 2004. - Ed. SR

Sri Guru Granth Saheb (SGGS) is an integral part of Sikh ethos and society as well as the basic beliefs. Its blessings are sought during all rites of passage. Its recitation is conducted on all occasions, happy or sad, for seeking inspiration and solace. It is accepted as it is given to us in print, in separate words, standardization of pages, easy for reference. It is not easy to imagine the original form in calligraphy with all words attached to each other in a line. Therefore what we have now is the result of a dedicated effort of researchers and scholars who have spent a lifetime in deciphering the early text, and keeping the authentic compositions of the spiritual Masters without any change in the punctuation or formation of a word. Since the birhs were written in hand, there were various developments over a period of time. The copying mode provided scope for the reproducer to include that which he considered to be appropriate. Moreover, there were persons who were jealous of the house of the Gurus and wanted to insert some of their own compositions. This came to be known as kachhi baani (unripe compositions, in other words, not authentic). In this way developed three texts that differed in terms of inclusions and exclusions from the original. In some, the compositions of the Ninth Guru were not included, while in others the raagmala, and some other compositions, not of the Gurus or the saints, were included. There was, therefore, a need for an authentic and authorized version of the SGGS so that the devotees were not subjected to spurious compositions and develop faith around the fake. It is also pertinent to realize that there was fear of some of the texts being lost or submerged in the process of copying wherein the copiers could exercise their discretion. An examination of some of the holy texts of other religions proves the point that most of the compositions were lost in the course of time. The Fifth Guru was conscious of the loss to the texts of other holy books. Due to the oral tradition of rendering the Vedas, much of the compositions are lost to posterity. The same happened in the case of Puranas that is left with only 5461 verses out of around 23000. The Buddhist scriptures contained in the Tripitakas are not considered the complete teachings of the Budhha. According to researches, there were only 10,000 slokas in the Mahabharata, now there are 30,000. It is not known how and when the additions were made. The Guru was also cognizant of the attempts made by his brother Prithichand who had attempted alterations. The mode applied by the Fifth Guru to ensure that nothing was added to the Granth was to put a seal on the compositions, in order to prevent any additions to the authorized text. For this purpose, he composed the Mundavani that was both an invocation and a humble expression of thanksgiving for the accomplishment of the gigantic task. Therefore, Mundavani is considered as the final verse of the text. It is the culmination of the process.

Even the Tenth Guru added the compositions of the Ninth Guru before the Mundavani and not after it. The Granth was completed in the year 1604 at Sabbo Talwandi. Mundavani is therefore a stamp or a seal that indicates that it is the finale of the text and there is nothing after that. It implies that anything contained in the text after the Mundavani is to be considered as an addition and not a part of the same. Then, how is it that there is Raagmala at the end of the Granth? This is the conundrum that has engaged scholars over time. It is also the theme of the book by Giani Gurdit Singh who has, through research and argument, concluded that Raagmala is not part of the text, anointed by the Gurus, but an addition in subsequent time, probably by Bhai Banno, as it is contained in the Banno birr and copies thereof, that even contained other compositions like Ramkali rattanmala, Hakikat rah mukaam, etc. However, this appears to be a consequence of the non-availability of standardized version of the compilation as it was not in printed form, and provided flexibility to the copiers to use discretion, there being no check as such. Then over a period of time, a controversy developed after the scholars searched for the authentic version. But two schools appeared. One believed that the Raagmala was a composition of Alam who wrote his long poem 21 years before the compilation of the SGGS, while others asserted that Alam lived in the time of Aurangzeb and had stolen the Raagmala from the SGGS to include this in his Madhavalan Kamkandla. This led to a scholarly exploration by Hindi and Punjabi scholars and it was finally established by researchers that Alam was a contemporary of Akbar, and the raagmala was a part of his text in stanzas 63-72 of his composition. Besides the claim of the scholars that it was a composition of poet Alam, there are other arguments adduced to convince that it was not a part of the SGGS. The theme of the raagmala does not conform to the overall tenor of the Granth. There is no indication of any of the ethos for which the holy text stands. It is only a genealogical refrain of the raags in the normal form. There are also raags and raaginis, that is, their male and female forms, as well as the sons of the consorts. It must be borne in mind that there was a tradition of giving shape to the sounds in order to add to the salient and significance and the satisfaction of the patrons who, in their imagery of the raga or the ragini, appeased their senses. This was also the beginning of the schools of paintings based on the raga themes. A raag is only a sound and nothing more. There is no mention of the ragini in the SGGS. Moreover, the holy text has only 31 ragas and 17 ghar, while the Raagmala has mentioned a set of 84 members in the extended family 6 primary ragas, 30 raginis (five consorts of each raga), and 48 sons (six sons of each couple). The latter is only an attempt at visualization of the sounds in order to give more taste to the senses. The editing of the SGGS has been meticulous - in the sense that not only are the raags prescribed for the compositions, but also the further instructions as to be sung in a certain tradition like that of Yanarey ke ghar gawna, Peherain ke ghar gawna, Ek suan ke ghar gawna, Gauri bi Sorath bi, Raney kailash tathha malwey ki dhun, Tundey aasraj ki dhuni (Asa di Var), Suan ke ghar gawna, Rai mehmey hasney ki dhun, Malak murid tathha suheyan ki dhuni gawnee, etc. The Guru was meticulous in describing the manner the composition was to be rendered. He could not have countenanced any deviation from the norm or permitted a composition that was at variance with the main structure of the raags in the text. Nine of the raags included in the holy text do not find any place in the raagmala. These are Manjh, Bihagra, Vad-hans, Jaitsri, Ramkali, Malli Gaura, Tukhari, Prabhati, and Jaijawnti. And all the raags of the raaagmala are not part of the text that has only 31 refrains. So it is not likely that this composition would have found any favor with the Guru who had taken intense pains to edit the text.

Another significant deviation is in the numbering process. The Guru had diligently numbered the compositions and added these at the end of each raag. For example, each verse has a number, and a composition has a total thereof, at the end. Secondly, at the beginning of each composition, there is a distinct reference to the author, like Mahilla pehla, dooja, teeja, and so on. All the compositions of the Bhagats (saints) have their names inscribed with a suffix Ji in reverence to them. But there is no authorship ascribed to the raagmala. It just starts as such. There is no reference to its authorship, as has been the practice in the all the foregoing 1429 pages of the text. Besides, all the stanzas of the raagmala are numbered 1. This seems incongruous in view of numbering of each line in all other compositions. Thus it may be inferred that the raagmala did not have the blessings of the Guru who had concluded the compilation at the Mundavani, thus putting a seal on the text so that it could not be altered in any form. It is, therefore, significant that the raagmala appears after the Mundavani, not before it. If the Guru had anointed it, he could have easily done so before putting his final seal as the composition had already existed 21 years earlier. That this was not done like that is an evidence of the fact that either the Guru had not come across this poem or he did not approve of it as befitting the overall tenor of the holy text. The final shape to the compilation was given by the Guru Gobind Singh, the Tenth Guru, who completed the authenticated version at Sabbo Talwandi, thus including the compositions of the Ninth Guru. There are references to this fact by many scholars. The myth that the concept of raags and raaginis had appealed to the Guru for inclusion is beyond the logic of editing of the SGGS. The work presents a forceful argument that the SGGS ends at Mundavani, that raagmala is a composition of Alam, that it was included by Bhai Banno, and therefore it is not a composition of the Gurus and hence, by implication not to be accepted as an utterance of the Guru and thus not deserving of the eminent position of being the culmination of the holy text at the time of akhand path. The author has, in his painstaking study, drawn copiously from the researches of scholars, examined many birrs, and supports his thesis with the help of many photographs and source material. Having established that raagmala is not part of the SGGS and consecrated by the Gurus, how is it that it continues to be a part of the printed Granth? The author has tried to refer to this in an indirect way. In this context the role of two scholars and one premier Sikh institution is under the scanner. The two prominent Sikh scholars had reversed their stand and supported the Raagmala, one on the basis of a Hindi source that was proved later on, by research, to be wrong, and based upon false and imaginary premises. The other scholar recanted, it appears, under the patronage of an institution that provided him with extensions in the job. Similar was the role of the Shiromini Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee (SGPC) that had adopted a constant refrain that Raagmala was not part of the SGGS and whose pronouncements had helped courts decide cases as there were problems in Kuala Lumpur (1907 and 1910), Nairobi (1917) and other places. But then under the political circumstances or compulsions (either not explored by the author or not indicated intentionally), the SGPC came out with a resolution that it should be left to the individual to recite the Raagmala as its recitation neither benefitted nor its exclusion harmed. How this neutral stand emanated remains a mystery till some scholar delves into the recesses of reason. There is one clue. Whereas the religion consultative committee had, in 1937, proposed and decided that the bhog should be at Mundavani, some people followed the dictate while others did not. In 1945, elections to both the assembly and the SGPC were to be held. Since the issue had become contentious, the status quo was proposed and the matter was left to the devotees.

For the time being, the Raagmala remains a part of the printed text and is generally being recited at the conclusion of the path (recitataion). The holy text has 1430 pages whereas the hand written ones have a variation like 533 pages in Kartarpur Birh, 557 in the Patiala, 590 in the Patna, 278 in the Baba Ala Singh Burj, and 517 and 596 in the Birhs with the author. This is clear from the photographs in the book. Thus the pagination task has rendered referencing possible. It is the contribution of the printed version that is now available in word form and not one sentence in one line formation. This has enabled the devotee to read the text properly. Having established, for the time being, that the Raagmala was not ordained by the Gurus, it begs an answer whether it is strictly appropriate to recite it. As has been mentioned above, there is no consensus at this stage. The issue seems to be pending with the SGPC. It could be a hot potato for handling. However, since Raagmala is part of the printed version, it continues to be recited generally. Maybe the devotee feels that it is purely a genealogical table and taxonomy of the ragas and has no reference whatsoever to the fable of love between the poet and the court dancer! There is no mention of the author. It appears as an independent composition with a flavour of being neutral. Since the devotees do not know the source and the context, they could find it as an invocation to the glory of the raags. And since almost all the compositions of the SGGS are set to music, perhaps, the devotee feels, this is not out of place even though it does not conform to the number of the raags in the holy text. It is only a recitation of the names of the raags, and nothing more. Hence it continues to be accepted as part of the text. There is all likelihood that so long it is part of the SGGS in its printed form, it shall continue to be recited, as after having read 1429 pages, one may not inclined to leave one last page unread. When the person bows to the SGGS as Guru, he does so to the whole and not the whole minus one page. Hence the practice of recitation of the whole text has continued. Giani Jis book is nevertheless worthy of sober attention and can be the basis for any mandate by the Akal Takht, should the community require settlement of the issue once and for all. But this appears to be a big if as the community may not be prepared to risk a controversy that could divide it into two pedantic camps: those adhering to the tradition, as it appears in practice at the moment, and those who side with research scholars.

GEETA AMRIT (Punjabi) [Pp. 144, Price: Rs. 30 (Paperback)] SADACHAR DA MARAG (Punjabi) [Pp. 102 Price: Rs. 25 (Paperback )]

By (Late) Prof. Harnam Das [Ed. by Dr. Amrit Kaur Raina] Published by Udaan Publications, Mansa (Punjab) 151505 A Review by Saran Singh The late Prof. Harnam Das, MA (Punjabi & Persian) held the post of head of Deptt.of Punjabi, S.D. College, Ambala Cant. A prolific writer and profound oriental scholar, several of his articles were featured in The Sikh Review during the Journals initial two decades in 1960s and 1970s. His gifted daughter, Amrit Kaur Raina, Principal Mata Gujari College for Girls at Sardulgarh, District Mansa (Punjab) is blessed with a rare catholicity of mind and thought, at home with Indian literature and philosophy whether that is inherent in Guru Granth Sahib or in various later strands of thought, such as the devotional phase of Ramakrishna Paramhansa. The two slim volumes (in Punjabi) have been published as her tribute to late Prof.

Harnam Das. The first embodies - the quintessential message of Bhagwat Gita, in chaste Punjabi, all the 18 chapters of the ancient classic that spells the divine message of Sri Krishna imparted to - and through Arjuna. Sri Krishnas life is a living legend, while his teachings are the daily lore for millions of Hindus. His clarion declaration: I am the Lord and Master, the Refugee, the Creator, Destroyer, Everlasting [Ch. IX, st.18] finds an echo in the Biblical saying of Jesus: I am the Resurrection and the life The book on morality (Sadachar da - Marag) dwells intensively on Naam Simran, and pulsates with stories from Guru Nanaks life and travels. There is a lesson on every aspect of life: of purity, the qualities of head and heart, secret of inner happiness, service of mankind and sheer joy of truthful living and chivalry. Throughout, her mellifluous Punjabi prose is the soul of simplicity. Amrits Labour of Love deserves a place in every library and home.

Вам также может понравиться

- Gita by Swami Adgadananda (Yatharth Gita)Документ430 страницGita by Swami Adgadananda (Yatharth Gita)Sanjay Pandey100% (1)

- Appsc Group 1 Previous PapersДокумент118 страницAppsc Group 1 Previous PapersRaj P Reddy Ganta71% (7)

- Gurbani With English Commentary (Volume 1)Документ608 страницGurbani With English Commentary (Volume 1)Sikh TextsОценок пока нет

- Encyclopedia of Sikh Religion and Character by DR Gobind Singh Mansukhani PDFДокумент561 страницаEncyclopedia of Sikh Religion and Character by DR Gobind Singh Mansukhani PDFDr. Kamalroop Singh100% (2)

- T. K. V. Desikachar - The Heart of Yoga - Developing A Personal Practice (1999, Inner Traditions)Документ266 страницT. K. V. Desikachar - The Heart of Yoga - Developing A Personal Practice (1999, Inner Traditions)JohnTmcОценок пока нет

- Guru Granth Sahib DarshanEngДокумент344 страницыGuru Granth Sahib DarshanEngSanu Maan Punjabi Hon Da75% (4)

- PDFДокумент18 страницPDFapi-396266235Оценок пока нет

- About Sri Sainathuni Sarath Babuji in The 'Mountain Path' Magazine.Документ9 страницAbout Sri Sainathuni Sarath Babuji in The 'Mountain Path' Magazine.Karna Info Design (Carlos)100% (1)

- Concepts SikhismДокумент28 страницConcepts Sikhismmusic2850Оценок пока нет

- Creativity and IntelligenceДокумент25 страницCreativity and Intelligencejeremiezulaski50% (2)

- Sau Sawal by Principal Satbir Singh PDFДокумент185 страницSau Sawal by Principal Satbir Singh PDFDr. Kamalroop Singh0% (1)

- Comparative Study of Hindi and Punjabi Language SCДокумент18 страницComparative Study of Hindi and Punjabi Language SCAshish GroverОценок пока нет

- History of Compilation of Guru Granth SahibДокумент6 страницHistory of Compilation of Guru Granth Sahibgoraya15Оценок пока нет

- The History of The Nitnem BĀņiĀ - Akali DR Kamalroop Singh NihangДокумент10 страницThe History of The Nitnem BĀņiĀ - Akali DR Kamalroop Singh NihangDr. Kamalroop SinghОценок пока нет

- SJC-Atri-Class-4: Yogas- Part-2Документ4 страницыSJC-Atri-Class-4: Yogas- Part-2S1536097FОценок пока нет

- Guru Granth SahibThe HistoryДокумент13 страницGuru Granth SahibThe HistoryHarpreet SinghОценок пока нет

- Essence of Srimad Bhagvad Gita: Commentary on selected 90 versesОт EverandEssence of Srimad Bhagvad Gita: Commentary on selected 90 versesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Articles On Yoga InjuriesДокумент94 страницыArticles On Yoga InjuriesKathryn MoynihanОценок пока нет

- The Arapachana SyllabaryДокумент5 страницThe Arapachana SyllabarymgijssenОценок пока нет

- Appreciation of Gurmat Sangeet V4Документ18 страницAppreciation of Gurmat Sangeet V4Dr. Kamalroop SinghОценок пока нет

- It Is the Same Light: The Enlightening Wisdom of Sri Guru Granth Sahib (Sggs) Volume 6: Sggs (P 1001-1200)От EverandIt Is the Same Light: The Enlightening Wisdom of Sri Guru Granth Sahib (Sggs) Volume 6: Sggs (P 1001-1200)Оценок пока нет

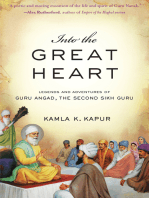

- Into the Great Heart: Legends and Adventures of Guru Angad, the Second Sikh GuruОт EverandInto the Great Heart: Legends and Adventures of Guru Angad, the Second Sikh GuruОценок пока нет

- GURU GRANTH SAHIB JI FinalДокумент30 страницGURU GRANTH SAHIB JI FinalJasmine Kaur 2K21/MSCCHE/23Оценок пока нет

- Sri Dasam Granth Sahib Questions and AnswersДокумент9 страницSri Dasam Granth Sahib Questions and AnswersGurinder Singh Mann100% (2)

- It Is the Same Light: The Enlightening Wisdom of Sri Guru Granth Sahib (Sggs) Volume 5: Sggs (P 801-1000)От EverandIt Is the Same Light: The Enlightening Wisdom of Sri Guru Granth Sahib (Sggs) Volume 5: Sggs (P 801-1000)Оценок пока нет

- Balwant Singh Search Into The History of The Text of Dasam GranthДокумент38 страницBalwant Singh Search Into The History of The Text of Dasam GranthLakhvinder SinghОценок пока нет

- Arati-Arata by DR Kamalroop Singh (Akali Nihang) PDFДокумент47 страницArati-Arata by DR Kamalroop Singh (Akali Nihang) PDFDr. Kamalroop Singh88% (8)

- Boundless Scripture of Guru Granth SahibДокумент18 страницBoundless Scripture of Guru Granth SahibRicha Budhiraja100% (1)

- Guru Grant H Sahib Among The Scriptures of The WorldДокумент270 страницGuru Grant H Sahib Among The Scriptures of The Worldsebastian431Оценок пока нет

- Gobind PDFДокумент110 страницGobind PDFaddy yОценок пока нет

- Bibliography of Sri Guru Granth Sahib JiДокумент36 страницBibliography of Sri Guru Granth Sahib JiMahender Singh Griwan100% (1)

- Kavi DurbarДокумент6 страницKavi DurbarJagjit SinghОценок пока нет

- Ishavasya Talavakara Kathaka Upanishads According To Sri Madhvacharya's BhashyaДокумент156 страницIshavasya Talavakara Kathaka Upanishads According To Sri Madhvacharya's BhashyaSubhash BhatОценок пока нет

- Exegesis of Sri Guru Granth Sahib in Singh Sabha School: A Critical StudyДокумент10 страницExegesis of Sri Guru Granth Sahib in Singh Sabha School: A Critical StudyHEERA SINGH DARDОценок пока нет

- Ghar 2Документ6 страницGhar 2Anonymous 5uPEDI6Оценок пока нет

- The History and Structure of Sikh Nitnem BāṇiāДокумент10 страницThe History and Structure of Sikh Nitnem Bāṇiāਕਿਰਨ ਸਿੰਘ ਵਿਰਕ ਖਾਲਸਾОценок пока нет

- Ami Shah AbstractДокумент3 страницыAmi Shah AbstractDr. Kamalroop SinghОценок пока нет

- Janamsakhis - Biographies of Guru Nanak Dev JiДокумент3 страницыJanamsakhis - Biographies of Guru Nanak Dev JiManjot Singh SinghОценок пока нет

- Sree Narayana GuruДокумент6 страницSree Narayana GurudrgnarayananОценок пока нет

- SPA Guru Granth Sahib Ji 1st PrakashДокумент2 страницыSPA Guru Granth Sahib Ji 1st PrakashgwlpspОценок пока нет

- Lecture Transcript On GBGДокумент7 страницLecture Transcript On GBGmaverick6912Оценок пока нет

- The Traditional View About The Sri Dasam Granth Sahib - The Global Vision of Guru Gobind Singh That IsДокумент4 страницыThe Traditional View About The Sri Dasam Granth Sahib - The Global Vision of Guru Gobind Singh That Isdasamgranth.comОценок пока нет

- Raagmala - A Book ReviewДокумент1 страницаRaagmala - A Book ReviewGurinder Singh MannОценок пока нет

- Guru Granth SahibДокумент15 страницGuru Granth SahibambrosialnectarОценок пока нет

- Arati ArtaДокумент48 страницArati ArtaNikhilОценок пока нет

- Guru Granth Sahib Little Taste PDFДокумент12 страницGuru Granth Sahib Little Taste PDFG SОценок пока нет

- Kartbir 1Документ126 страницKartbir 1Nirbhay DhimanОценок пока нет

- 6 SimranДокумент9 страниц6 SimranSanjay Chandwani100% (1)

- 9 ShabadKirtanДокумент28 страниц9 ShabadKirtanSanghОценок пока нет

- Sudhanshu Medieval DeccanДокумент11 страницSudhanshu Medieval Deccanmovies7667Оценок пока нет

- Pali BodhivamsaДокумент3 страницыPali BodhivamsaBORALANDE DHAMMARATANA100% (1)

- Poetics and Meyters of Gurbani Explaine - Kaav Prakash - Roop Deep PingalДокумент51 страницаPoetics and Meyters of Gurbani Explaine - Kaav Prakash - Roop Deep PingalUday SinghОценок пока нет

- An Introduction To Gurmat Sangeet.: History, Evolution and Topics For Further ResearchДокумент12 страницAn Introduction To Gurmat Sangeet.: History, Evolution and Topics For Further ResearchDr Kuldip Singh DhillonОценок пока нет

- Charya GeetДокумент11 страницCharya Geetmindoflight100% (1)

- Historical Analysis of Combined Recensions of Guru Granth Sahib and Sri Dasam GranthДокумент3 страницыHistorical Analysis of Combined Recensions of Guru Granth Sahib and Sri Dasam GranthJapjee SinghОценок пока нет

- Isha PrefaceДокумент9 страницIsha PrefaceRama PrakashaОценок пока нет

- Bindu 341Документ4 страницыBindu 341ISKCON Virtual TempleОценок пока нет

- Formulating Methodology For InterpretingДокумент9 страницFormulating Methodology For Interpretinggursewak78Оценок пока нет

- Paramahansa Yogananda - A TributeДокумент7 страницParamahansa Yogananda - A TributeDr Srinivasan Nenmeli -KОценок пока нет

- How To Find A Guru - Indiaspirituality BlogДокумент4 страницыHow To Find A Guru - Indiaspirituality BlogIndiaspirituality Amrut100% (1)

- Udasi LiteratureДокумент53 страницыUdasi Literaturesukhbir24100% (3)

- A Comparative Study of Early Buddhist Dharmapada CollectionsДокумент309 страницA Comparative Study of Early Buddhist Dharmapada CollectionsHerick RendellОценок пока нет

- Relevance of Dasam GranthДокумент3 страницыRelevance of Dasam Granthjass_manutdroxОценок пока нет

- 18 The One Name Is The Divine CommandДокумент6 страниц18 The One Name Is The Divine Commandparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 8 Learn To Trust PDFДокумент4 страницы8 Learn To Trust PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 15 Divine Importance of Our Deeds PDFДокумент3 страницы15 Divine Importance of Our Deeds PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Diabetes Information BookletДокумент28 страницDiabetes Information BookletheenamodiОценок пока нет

- 14 Follow The Hukam PDFДокумент8 страниц14 Follow The Hukam PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 13 Sat Santokh Contentment With TruthДокумент3 страницы13 Sat Santokh Contentment With Truthparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 15 Divine Importance of Our Deeds PDFДокумент3 страницы15 Divine Importance of Our Deeds PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- English To Hindi Dictionary Roman LipiДокумент717 страницEnglish To Hindi Dictionary Roman Lipisonuakhil60% (5)

- 6 Staying On The Path Passing The Tests PDFДокумент6 страниц6 Staying On The Path Passing The Tests PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 10 Patsahyan Da Jeevan For VillДокумент5 страниц10 Patsahyan Da Jeevan For Villparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- List of Abbreviations of The Month of July 2013Документ1 страницаList of Abbreviations of The Month of July 2013parminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 8 Learn To Trust PDFДокумент4 страницы8 Learn To Trust PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 12 Make Your Life Truthful Some Tips PDFДокумент3 страницы12 Make Your Life Truthful Some Tips PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Lern AccountsДокумент4 страницыLern Accountsparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 11 Kindness A Divine Quality PDFДокумент2 страницы11 Kindness A Divine Quality PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Understanding the true meanings of Satnaam and WaheguruДокумент12 страницUnderstanding the true meanings of Satnaam and Waheguruparminder2119850% (1)

- 9 Key Divine Laws PDFДокумент8 страниц9 Key Divine Laws PDFparminder211985100% (1)

- 5 Greeting The Guru Dandauth PDFДокумент4 страницы5 Greeting The Guru Dandauth PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Meditation Naam Simran PDFДокумент9 страницMeditation Naam Simran PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 5a Ardas Before Going To Sleep PDFДокумент13 страниц5a Ardas Before Going To Sleep PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- How To Do Simran in 4 StepsДокумент17 страницHow To Do Simran in 4 Stepsparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Spiritual Guidance PDFДокумент14 страницSpiritual Guidance PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 28 The Steps To God Realization PDFДокумент4 страницы28 The Steps To God Realization PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 4 Honest Work PDFДокумент2 страницы4 Honest Work PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- 3 Forgiveness PDFДокумент6 страниц3 Forgiveness PDFparminder2119850% (1)

- 1 The Practise of WisdomДокумент5 страниц1 The Practise of Wisdomparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Gurbani Questions PDFДокумент13 страницGurbani Questions PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Digitally Sign and Email Form 16/form 16AДокумент1 страницаDigitally Sign and Email Form 16/form 16Aparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Qaa 23 April 2010 PDFДокумент4 страницыQaa 23 April 2010 PDFparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- Curriculum-Vitae: Parminder SinghДокумент2 страницыCurriculum-Vitae: Parminder Singhparminder211985Оценок пока нет

- TimesofindiaДокумент30 страницTimesofindiaGopi GopinathanОценок пока нет

- Nabard Grade A English Part 40Документ26 страницNabard Grade A English Part 40Sabari SwaminathanОценок пока нет

- Ancient Indian Tradition and Mythology SourcesДокумент64 страницыAncient Indian Tradition and Mythology SourcesRavindra LeleОценок пока нет

- Pune ResultttghgiДокумент1 страницаPune ResultttghgiGaurav PatilОценок пока нет

- Yantrodaraka Hanuman StutiДокумент3 страницыYantrodaraka Hanuman StutiDeepak KrishnamurthyОценок пока нет

- Srila Prabhupada Puja and Murti Care StandardsДокумент4 страницыSrila Prabhupada Puja and Murti Care StandardsOriol Borràs FerréОценок пока нет

- Meditation Times Jan 2012Документ126 страницMeditation Times Jan 2012Taoshobuddha100% (2)

- HH Jayapataka Swami Guru Maharaj, Caitanya Lila Book Compilation, Chennai, 2 February 2019Документ5 страницHH Jayapataka Swami Guru Maharaj, Caitanya Lila Book Compilation, Chennai, 2 February 2019dwijenОценок пока нет

- Sample Notes For History OptionalДокумент24 страницыSample Notes For History Optionalatri394Оценок пока нет

- Sunil Kumar VishwakarmaДокумент5 страницSunil Kumar VishwakarmaAnonymous qHCvNxswckОценок пока нет

- School and CollegeДокумент150 страницSchool and CollegeAl Mamun AhmedОценок пока нет

- Modern Essays Notes for BA English (4th yearДокумент44 страницыModern Essays Notes for BA English (4th yearNaeem AkhtarОценок пока нет

- Communication HandbookДокумент74 страницыCommunication HandbookAnujit JenaОценок пока нет

- Review of Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions From South Asia, Ed. Sheldon PollockДокумент3 страницыReview of Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions From South Asia, Ed. Sheldon PollockBen Williams0% (1)

- Introduction To Backword Class Dept of KarnatakaДокумент52 страницыIntroduction To Backword Class Dept of KarnatakarajakumarttОценок пока нет

- PATENT Annexure-A Domestic FilingДокумент24 страницыPATENT Annexure-A Domestic FilingMulayam Singh YadavОценок пока нет

- Yoyo YogaДокумент18 страницYoyo YogaArmaandeep DhillonОценок пока нет

- Characteristics of Indian Literature: Bon Michael Jaraula SEPTEMBER 5, 2014 8-CEZ EnglishДокумент6 страницCharacteristics of Indian Literature: Bon Michael Jaraula SEPTEMBER 5, 2014 8-CEZ EnglishBelleMichelleRoxasJaraula0% (1)

- Is Savitar Really A Hindu God of Speed?: Scribd Search Search Search Upload EN Change Language Read Free For 30 DaysДокумент17 страницIs Savitar Really A Hindu God of Speed?: Scribd Search Search Search Upload EN Change Language Read Free For 30 DaysAniruddha_GhoshОценок пока нет

- 06 Dec-2023 (Morning Shift - ETE)Документ328 страниц06 Dec-2023 (Morning Shift - ETE)harshgupta.16018Оценок пока нет

- Nadia District - WikipediaДокумент13 страницNadia District - WikipediaSaroj kumar BiswasОценок пока нет

- Final BookДокумент66 страницFinal Booksantu1911100% (1)

- 21Документ9 страниц21Yashashvi RastogiОценок пока нет

- APPWW Opposition To St. Paul ResolutionДокумент3 страницыAPPWW Opposition To St. Paul ResolutionPGurusОценок пока нет

- Annexure A & Annexure BДокумент2 страницыAnnexure A & Annexure BCrws BhopalОценок пока нет