Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Making of Metropolitan Delhi - Baviskar

Загружено:

Shamindra RoyИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Making of Metropolitan Delhi - Baviskar

Загружено:

Shamindra RoyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Between violence and desire: space, power, and identity in the making of metropolitan Delhi

Amita Baviskar Introduction

who paid to have a wall constructed between the dirty, unsightly jhuggis and their own homes. Delhi, on the morning of January 30, 1995, was The wall was soon breached, as much to allow waking up to another winter day. In the well-to- the trafc of domestic workers who lived in the do colony of Ashok Vihar, early risers were jhuggis but worked to clean the homes and cars setting off on morning walks, some accompa- of the rich, wash their clothes, and mind their nied by their pet dogs. As one of these residents children, as to offer access to the delinquent walked into the neighbourhood park, the only defecators. Dilips death was thus the culmination of a open area in the locality, he saw a young man, poorly clad, walking away with an empty bottle long-standing battle over a contested space that, to one set of residents, emin hand. Incensed, he bodied their sense of gracaught the man, called his Amita Baviskar is a sociologist at the cious urban living, a place of neighbours and the police. University of Delhi, India. Her research trees and grass devoted to A group of enraged houseaddresses the cultural politics of environment and development. Her publications leisure and recreation, and owners and two police coninclude the book In the Belly of the River: that to another set of resistables descended on the Tribal Conicts over Development in the dents, was the only available youth and, within minutes, Narmada Valley, Oxford University Press, space that could be used as a beat him to death. 1995. toilet. If he had known this The young man was history of simmering con18-year-old Dilip, a visitor ict, Dilip would probably to Delhi, who had come to have been more wary and watch the Republic Day would have run away when parade in the capital. He challenged, and perhaps he was staying with his uncle in would still be alive.1 a jhuggi (shanty house) This incident made a along the railway tracks bordering Ashok Vihar. His uncle worked as a profound impression on me. During my research labourer in an industrial estate nearby which, in central India, the site of struggles over like all other planned industrial zones in Delhi, displacement due to dams and forestry projects had no provision for workers housing. The as well as the more gradual but no less jhuggi cluster with more than 10,000 households compelling processes of impoverishment due to shared three public toilets, each one with eight insecure land tenure, I had witnessed only too latrines, effectively one toilet per 2083 persons. often state violence that tried to crush the For most residents, then, any large open aspirations of poor people striving to craft basic space, under cover of dark, became a place to subsistence and dignity (Baviskar 2001). Now I defecate. Their use of the park brought them was watching a similar contestation over space up against the more afuent residents of the area unfold in my own back yard. I had previously

ISSJ 175 r UNESCO 2003. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA

90

Amita Baviskar

analysed struggles over the environment in rural India; now my attention was directed towards how, in an urban context, the varied meanings at stake in struggles over the environment were negotiated through different projects and practices. This concern has been strengthened over the last 2 years by two sets of processes, each an extraordinarily powerful attempt to remake the urban landscape of Delhi. Through a series of judicial orders, the Supreme Court of India has initiated the closure of all polluting and nonconforming industries in the city, throwing out of work an estimated 2 million people employed in and around 98,000 industrial units. At the same time, the Delhi High Court has ordered the removal and relocation of all jhuggi squatter settlements on public lands, an order that will demolish the homes of more than 3 million people. In a city of 12 million people, the enormity of these changes is mind-boggling. Both these processes, which were set in motion by the ling of public interest litigation by environmentalists and consumer rights groups, indicate that bourgeois2 environmentalism has emerged as an organised force in Delhi, and upper-class concerns around aesthetics, leisure, safety, and health have come signicantly to shape the disposition of urban spaces. This bourgeois environmentalism converges with the disciplining zeal of the state and its interest in creating legible spaces and docile subjects (Scott 1998). According to Alonso (1994: 382), modern forms of state surveillance and control of populations as well as of capitalist organisation and work discipline have depended on the homogenising, rationalising and partitioning of space. Delhis special status and visibility as national capital has made state anxieties around the management of urban spaces all the more acute: Delhi matters because very important people live and visit there; its image reects the image of the nation-state. As an embodiment of Indias modernist ambitions, the capital has been diligently planned since 1962 when the rst Master Plan was produced with the help of American expertise supplied by the Ford Foundation. The Master Plan would order Delhis landscape in the ideal of Nehruvian socialism, and enlightened state control would engineer functional separation, leaving a sanitised slot for history in the form of protection for monuments deemed archaeologically

important (Khilnani 1997). Huge tracts of agricultural land were acquired from the villages close to the city and vested with the Delhi Development Authority (DDA)3 which had the monopoly of transforming these spaces into zones appropriate for a modern capital: commercial centres, institutional areas, sports complexes, green areas, housing colonies, and industrial estates. Lending urgency to their ambitions was the presence of around 450,000 Hindu and Sikh refugees4 who had ooded the city from what had become Pakistan, and who had been settled on the periphery of the city in housing colonies, but whose sewage had contaminated the citys water supply, leading to 700 deaths from jaundice in 1955 (Saajha Manch 2001: 5). Concerns about the physical and social welfare of concentrated human populations were thus channelled into the desire for a planned city, where they converged with the high nationalist fervour for modernisation. Fullling this desire seemed to be pre-eminently a responsibility of the state:5 the legitimacy of a national government that had the prestige of ghting for freedom added fresh power to an older development regime established by colonial capitalism (Ludden 1992) that gave the state primacy in the mission of Civilisation and Improvement.

The logic of the planned city

The land that the Delhi Development Authority surveyed was no empty space, but already vivid with embodied practices. There was the presence of the two imperial Delhis still extant cheek-byjowl: Shahjehanabad and New Delhi (Gupta 1981), and the new urban villages whose lands had been acquired by the DDA. Shahjehanabad, the Mughal walled city built and rebuilt from the sixteenth century onwards, was a mosaic of mixed use practices, where homes, work places, shops, places of worship and government were piled on top of each other in untidy profusion. To colonial eyes, this apparent anarchy had to be regulated in order to prevent the spawning of seditious thought and action. After the Mutiny/ First War of Independence in 1857, the colonial state demolished large parts of Shahjehanabad, laying down railway tracks that tore through its heart. The city was depopulated and ethnically

r UNESCO 2003.

Space, power and identity in the making of metropolitan Delhi

91

reconstituted in 1947 when its large Muslim population ed to the new state of Pakistan at the time of Partition. To the south of Shahjehanabad and looking down upon it, the British had built New Delhi in 1918, shifting the locus of empire on the subcontinent from Calcutta to Delhi. The cartography of colonial power was visible in the citys spatial design. There was the Central Vista where the Viceroys Palace surmounted the Parliament House, the Secretariat, and the palaces of the Native rulers. New Delhis wide avenues segregated the white rulers from the brown babus in a nely calibrated hierarchy of status, made visible through bungalow size, while also creating sites such as ofces and shopping areas where rulers and natives could transact business in a regulated fashion. The building of New Delhi had entailed the displacement of Untouchable castes who had lived south of Shahjehanabad and who were now banished to the western periphery of the new city.6 Thus the building of the capital of independent India began by encompassing both Shahjehanabad and New Delhi, as well as appropriating the lands of numerous villages around the city. The presence of these urban villages, with their unplanned residential settlements and their suspended rights to dispose of their agricultural lands, continues to be an anomaly that actively contradicts the logic of the planned city. From the beginning, the process of planning had to contend with multiple ways of imagining the city. There was the model of Shahjehanabad, which based itself on encouraging mixed land use, recognising and adapting to the complexity of a multi-ethnic, multi-class society with spatially overlapping functions. A stream of opinion within the urban planning movement, represented by Patrick Geddes who had travelled widely in India and had designed plans for several Indian towns, espoused this model of the planned city (Geddes 1915). Then there was the modernist model of spatial segregation of populations and functions. Planners did not weigh the pros and cons of these and other models in order judiciously to choose the one best suited to Delhis projected needs. While ostensibly a scientic-rational process that is free from politics, urban planning has always been about the exercise of power. In the case of Delhis Master Plan too, the disciplinary

aspects of creating and controlling subjects and spaces shaped the process of boundary-making. Crucial for the project of effective control was the generation of information: the enumeration of populations though the decennial census was supplemented by their classication into various economic categories. These were then mapped onto separated zones partitioning work and residence, industry and commerce, education, administration and recreation. Regulatory systems such as licensing, tax collection, labour and pollution inspection, and so on attempted to keep tabs on a burgeoning economy. Delhis Master Plan envisaged a model city, prosperous, hygienic, and orderly, but failed to recognise that this construction could only be realised by the labours of large numbers of the working poor, for whom no provision had been made in the plans. Thus the building of planned Delhi was mirrored in the simultaneous mushrooming of unplanned Delhi. In the interstices of the Master Plans zones, the liminal spaces along railway tracks and barren lands acquired by the DDA, grew the shanty towns built by construction workers, petty vendors, and artisans, and a whole host of workers whose ugly existence had been ignored in the plans. The development of slums was, then, not a violation of the Plan; it was an essential accompaniment to it, its Siamese twin. The legal geography (Sundar 2001) created by the Plan criminalised vast sections of the citys working class, adding another layer of vulnerability to their existence. At the same time, the existence of the slums over time was enabled by a series of on-going transactions: the periodic payment of bribes to municipal ofcials, and the intervention of local politicians. Planners attempts to map inexible legal geographies became a resource by which state ofcials and political entrepreneurs could prot, as they brokered deals that allowed slums to stay. Planners lamented the absence of political will, the apparent impotence of the municipal authorities to enforce the law, but failed to recognise their own complicity in creating a situation where illegal practices could ourish. Erasing (through criminalising) the necessary presence of the working class was thus not an oversight but rather intrinsic to the project of producing and reproducing powerful inequalities. This misrecognition was wilful and systematic, an institutionally organised and

r UNESCO 2003.

92

Amita Baviskar

guaranteed strategy of devising sincere ctions with the aim of reproducing relations of power between the state, spaces, and subjects (Bourdieu 1977: 171). The presence of this pool of cheap labour enabled the planned city to grow, even as its proximity raised the spectre of dirt, disease, and crime, a monster threatening the body civic that the state has since then been trying unsuccessfully to leash. The project of disciplining the poor was thus shaped by contradictory processes as planners, politicians, and municipal ofcials brought different agendas to bear upon the issue. Particular historical circumstances created conditions for negotiation and accommodation as well as repression and violence. A conjuncture that permitted the playing out of the totalitarian ambitions of planners was the State of Emergency (197577) where Prime Minister Indira Gandhis government suspended civil liberties in order to remain in power.7 With the active involvement of Gandhis son, Sanjay Gandhi (the unconstitutional power beside the throne), Jagmohan, the Lieutenant-Governor of Delhi,8 planned and supervised the demolition of slums from the heart of the walled city and their relocation on the swampy eastern edge of Delhi. Emma Tarlos study of Seelampuri (2002), one such resettlement colony, locates the Emergency as a critical event (Das 1995) that revealed the structural violence tying control over sexualised, communalised subjects to space. The strong public opposition to these excesses in the aftermath of the Emergency meant that disciplinary desires lay dormant for the next two decades. In the late 1970s, there was a spurt of construction in the capital with the immediate goal of building facilities for the Asian Games to be held in Delhi in 1982. This project, represented as one where national prestige was at stake, provided the grounds for the DDA to violate its own Master Plan and suspend procedural rules in order to enter into dubious contracts with construction rms. The building of yovers, sports facilities and luxury apartments (to house participating athletes, which have since become homes for senior bureaucrats), brought to the city an estimated one million labourers from other states. Once the construction was over, these labourers stayed on, often in shanty settlements in the shadow of the concrete structures they had built,

seeking other employment. In the early 1980s, their presence was tolerated and even encouraged by local politicians who secured for them water taps and ration cards for subsidised provisions. The populist governments at the Centre were willing to allow the migrants some recognition, albeit of a limited nature. While their concern did not extend to the provision of low-cost housing or civic amenities such as sanitation, electricity, schools, and health clinics, it did give workers a temporary reprieve in the battle to create homes around their places of work. But in the late 1980s, when newly instituted economic liberalisation policies threatened to end its monopoly, the DDA began to imagine a new role for itself in partnership with private builders. One of the steps towards this was the transfer of land on lease to cooperative group housing societies, usually of urban professionals, who constructed their own apartment complexes, in east and north-west Delhi. More afuent families shifted to the new suburbs being developed on the south-western edge of the city by private real estate rms. The unsatised demand for housing and spaces for commerce and recreation (and the two were fused in the idea of shopping as a leisure activity) by this class, drove up the value of real estate in the city, pressuring the DDA and the Delhi government to accelerate their mission of urban development so that they could enjoy higher prots (legal and illegal). The hurry to develop the land for commercial ends and gigantic urban projects highways, yovers, river-front development necessitates the removal of the jhuggi settlements that encroach on public land. Once again, the DDAs Master Plan seeks to orchestrate a transformation that will make Delhi an ideal urban space governed by the project of rule: the national Capital, in both material and symbolic terms. But the planners desire to effect a controlled and orderly manipulation of change has been continuously thwarted by the inherent unruliness of people and places. The limitations of modern techniques of power crucial for the planning enterprise soon became evident. Accurate numerical data essential for modern policy initiatives such as present and projected estimates of populations and their production and consumption patterns, proved impossible to generate because of the

r UNESCO 2003.

Space, power and identity in the making of metropolitan Delhi

93

magnitude, dynamism and complexity of the reality they sought to capture. Appadurai (1993: 317) has described how practices of enumeration were central to the illusion of bureaucratic control and a key to a colonial imaginary in which countable abstractions, of people and resources at every imaginable level and for every conceivable purpose, created the sense of a controllable indigenous reality. While being armed with data remains an important technique for justifying intervention, its dubious accuracy and failure to yield expected outcomes constantly rendered it open to challenge. Thus, for example, not only was the Delhi government recently reprimanded in the Supreme Court for supplying multiple and contradictory estimates of industrial units in Delhi and being unable to provide precise information about their production processes, but its inability to regulate these units was also manifested by the continued presence of high levels of air and water pollution in the city. Just as economic activities spill over and out of the taxonomies created by the state to regulate urban populations (for instance, household industry involves a combination of family labour and hired workers with varying skills and terms of employment), the mapping of functionally specic land-use zones is obliterated by a spectrum of unauthorised practices: workers without shelter (and unable to afford commuting costs) who crowd around their places of work; a land maa that brokers deals between municipal authorities and those with the capital to acquire and use land illegally; and political leaders who encourage encroachments with an eye towards cultivating vote banks among insecure squatter settlers.

Negotiating contradictions

From the interdependence between squatters and their political patrons, proteering property brokers and those looking for land, and lowerlevel bureaucrats who benet through turning a blind eye to violations, there emerge powerful collaborations that undermine the bourgeois dream of re-making the city. The states Master Plan is undone through resistance both internal and external. The displacement that the creation

of a clean and green Delhi entails has been held in check by the delicate political equations on which state legitimacy hinges. The orderly manipulation of people and places cannot rely on brute force alone, even though there have been several violent encounters in the process of enforcing the Supreme Court directives. Politicians across the party divide in the city recognise that their electoral fortunes depend on the support both of nanciers and of the numerically important poor. Negotiating the contradictions between these disparate constituencies, the city administrations responses to judicial orders have been heterogeneous: playing for time, pleading to change the rules, placating the judges with new plans, even as it hastens to assure threatened groups that it would protect their interests. The fractures within political authority, partly a consequence of Delhi being not just a city but the capital of India, help to create ambiguous spaces and irregular practices jurisdictional twilight zones where the buck can be passed to a bewildering number of authorities and no action taken. As expected from a heterogeneous group, the responses from the owners of industrial units in the city have been diverse. For a few large industrialists, those who owned factories in the centre of the city, this crisis is an opportunity to convert land to more protable commercial or ofce space. Others have moved to a new periphery, the industrial estates in nearby Rajasthan, where they will probably continue to pollute without check. Many owners of small rms assert that the installation of pollution control equipment, or the switch to non-polluting technologies, will render their operations economically unviable. That is, their prots depend on exploiting the environment. It is quite likely that some producers and small-scale production will simply go out of business, making way for more capital-intensive technologies. The ability to weather displacement varies with the material and symbolic capital at ones command. The Supreme Court issued directions about compensating factory owners as well as their employees. However, workers entitlements are conditional upon their being recognised as employees, their eligibility dependent on ofcially being on the rolls. Yet the same logic of keeping costs down that makes factory-owners

r UNESCO 2003.

94

Amita Baviskar

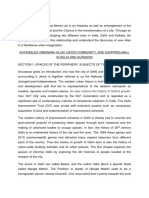

A woman looks for her belongings in the remains of a slum demolished in central New Delhi in June 2000.

Arko Datta/AFP

r UNESCO 2003.

Space, power and identity in the making of metropolitan Delhi

95

resist the enforcement of pollution laws operates to keep workers off the rolls. The intricacies of contracting and sub-contracting labour, designed to keep labour costs low and capitalists in control, prevent most workers from being recognised as displaced and liable for compensation from specic rms. Workers dependent on daily wages, with no job security and who are the most vulnerable of the citys poor are rendered completely destitute by this process of restructuring the urban economy. The insecure, constantly changing conditions of work that prevented their political organisation also make invisible the violence done to these workers. Free in Marxs doubly ironic sense to sell their labour wherever they please, without owning any capital, much of Delhis working class experiences displacement as a constant fact of life. The trade unions that represent the minority of ofcially recognised industrial workers have been protesting against the closure of industrial units and the displacement of workers in the courts and through mass demonstrations.9 Their arguments represent environmental concerns as antithetical to workers interests. A common accusation is that: shahar ko sundar banane ke liye ameer log mazdoor ke pet par laat maar rahe hain (to make the city beautiful, the rich are kicking workers in their belly). But this is only a partial account of the complex politics leading to displacement in which bourgeois environmentalism and Master Plans converge with other processes of capitalist restructuring and real-estate development. Nor is environmentalism an agenda that is antagonistic to working-class interests. Those most vulnerable to environmentally hazardous living and working conditions are most often the working-class. The economic compulsion of working in hazardous conditions and the political powerlessness of being unorganised, combined with the states failure to implement labour and environmental regulations, structure the conict in terms of a perceived opposition between jobs and the environment. Delhi is a city where the majority scrabble to nd a precarious foothold in the race for space and work, their housing concerns focused on getting access to sanitation, water, and electricity in squalid settlements. For them, the sheer uncertainty of employment makes unimaginable the asking of questions about

conditions of work, wages, security, and environmental hazard. Workers organisations have generally been ineffective in pointing out that a safe and clean working and living environment is equally a priority for workers. As Ravindran (2000: 116) observes: Four decades of urban planning in Delhi, which progressively marginalised both the urban environment and the poor, is now faking an encounter between the two.

Environment for whom?

Bourgeois desires for a clean and green Delhi have combined with commercial capital and the state to deny the poor their rights to the environment. Although the environment is seen as a luxury for those who can barely carve out a livelihood, attending to the struggles for work and home allows us to appreciate what the environment means across time to different groups as they are recongured by the contestations around place-making. The proliferation of deplorable squatter settlements, and the criminalisation of the working poor who live in them, is a direct consequence of processes of displacement written into the Master Plan. State monopoly over urban land, combined with the states failure to build or facilitate the construction of legal low-cost housing, makes slums the only possible option. While the bourgeois gaze regards these encroachments as disguring the landscape, for their residents the jhuggis represent a tremendous investment in terms of the capital and labour that has gone into making a habitable place: coordinating with other builders, laying out plots and lanes, putting in drains, improving building materials, negotiating with the municipal authorities, petitioning for toilets, schools, and healthcare. The visible difference between relatively new and old jhuggi settlements makes clear the incremental efforts that go into the making of homes and habitable neighbourhoods. With the passage of time, plastic sheets and bamboo thatch shacks are replaced with more sturdy plaster and brick, roads and drains are laid out, the tentative hope of permanence signied also by the carefully cultivated rose and sacred basil plants in recycled plastic containers that are lined beside front doors.

r UNESCO 2003.

96

Amita Baviskar

The hope of permanence is not a foolhardy fantasy. Slum-dwellers know that if they endure the hardship and hazard of being illegal residents, the fait accompli of encroachment can be a powerful argument for recognition and legal status. Over time, the claims of jhuggi-dwellers to be regularised become stronger, with the state either legalising their settlement or granting them alternative sites in resettlement colonies on the edge of the city. Having learnt to anticipate this sequence of conict and compromise, the poor and their political patrons willingly collaborate in the enterprise of encroachment, negotiating the risk of displacement in the hope of securing future recognition and permanent tenure. The slums, like the nonconforming and polluting industries that in the eyes of the Supreme Court are a violation of law, are for their residents the manifestation of years of compromise in which law enforcement agencies have been fully complicit. Preying upon working class hopes and dreams of a better future, these relations of conict and compromise are embedded in profound structural violence. The collective efforts of slum-dwellers who mobilise to improve and defend their modest homes, confronting demolition crews and doggedly rebuilding after the destruction, are sabotaged by the states promise of limited housing sites in resettlement colonies. Driven by the desire to secure legal housing and a stable foothold in the uncertain economy of the city, slum-dwellers abandon their collective struggle for individual gain. When the municipal trucks arrive to take people to the bleak resettlement sites on the citys outskirts, and the municipal ofcials begin handing out the slips of paper that promise a plot in these wastelands, there is a scramble to dismantle the homes painstakingly built brick by brick over the years, to be the rst to board the trucks. Arriving at the resettlement sites, bare tracts of land without any services, the poor tackle once again the arduous challenge of imagining and crafting liveable places. The civilising and improving mission of the state is thus realised by the labours of the poor, their sweat and blood and dreams. The making of Delhis working class is also bound to the perpetuation of their identity as migrants. A migrant identity, with its implication of belonging elsewhere, keeps the poor from being recognised as full residents of Delhi

entitled to the full complement of civic rights and social opportunities. Despite Delhis history as a city of migrants, where the overwhelming majority of the population consists of rst or second-generation migrants, the fact of migration is selectively used to stigmatise certain social groups. While attempts by the bourgeoisie to construct a genealogy explaining its presence in Delhi are granted legitimacy, similar strategies are denied to the property-less. Perceiving the poor as migrants and as newly arrived interlopers on the urban scene is a strategy to disenfranchise them from civic citizenship. This treatment is also inected by communal identications. When the Hindu nationalist party, the BJP, was in power both at the Centre and the Delhi state government during 199699, the names of thousands of Muslim slum-dwellers were deleted from the electoral rolls, on the grounds that they were illegal Bangladeshi immigrants. The presence of Bengali-speaking Muslims (assumed to be from Bangladesh) was used to strip all Muslims of their right to vote, in a context where there is no rm proof of national identity. The BJP has been keen to institute a system of surveillance based on identity cards as a mechanism for keeping Delhi from being swamped with migrants. Such a system could well become a way of dispensing patronage to certain social groups while excluding and stigmatising other cultural identities. These gate-keeping systems play upon bourgeois anxieties around the breakdown of urban infrastructure, their apprehensions about the scarcity of water and electricity, the increase in crime and disease, and the proliferation of unruly places and peoples.

Conclusion: Reform or transform Delhi?

In Delhi, the poor have responded to such disciplining attempts by adopting varied strategies of enterprise, compromise, and resistance. They have exercised their franchise as citizens (the vote banks that the bourgeoisie holds in contempt), used kinship networks, entered into unequal bargains with politicians and employers, mobilised collectively through neighbourhood associations, and most recently, attempted to create a coalition of slum-dwellers organisa-

r UNESCO 2003.

Space, power and identity in the making of metropolitan Delhi

97

tions, trade unions, and NGOs. This coalition, called Saajha Manch (Joint Forum), has over the last three years created a powerful critique of Delhis Master Plan, pointing to the absence of participatory processes in its formulation and highlighting the sharp inequalities in the consumption of urban resources. These multiple practices, simultaneously social and spatial, attempt to democratise urban development even as they challenge dominant modes of framing the environment-development question. This paper has shown that planned urban development, like other modes of state-making, attempts to transform the relations between populations and spaces, in the process displacing and impoverishing large sections of the citizenry. In the case of Delhi, state-making is not only about reproducing the state nationally and internationally and securing resources for capitalist restructuring, but it also includes interven-

tions aimed at improving the environmental quality of life for Delhis bourgeoisie. For the bourgeoisie as well as for poor migrants, processes of place-making are marked by both violence and desire (Malkki 1992: 24), as displacement collides with dreams of a better life. These subjects strategies to craft work and home, the central axes of social being and identity, are grounded in the negotiation of multiple and shifting elds of power (Moore 1998). Rather than seeing place-making as a project of rule, I have attempted to direct attention toward the accomplishment of rule (Li 1999), the contradictions and compromises that radically transform this project. Such an analysis seeks to identify and understand the complexities in the exercise of agency by subaltern subjects, as they attempt to intervene in the unequal processes of creating spaces and identities that are intrinsic to the project of urban development.

Notes

1. The violence did not end there. When a group of people from the jhuggis gathered to protest against this killing, the police opened re and killed four more people (PUDR 1995). 2. I am using the terms bourgeois and upper-class to refer to the group that is instantly recognisable in Delhi by dress, deportment, and language: the padhe-likhe (educated) and the propertied, white-collar professionals, and those engaged in business: the owners of material and symbolic capital. 3. The Delhi Development Authority (DDA) was constituted in 1957 by an Act of Parliament to check the haphazard and unplanned growth of Delhi. 4. In 1941, the population of the city had been 917,000. By 1951, the city had grown more than 50% because of the refugee inux. 5. While state intervention was taken as a given, the nature of the intervention was debated to some extent , as shown by the correspondence between Nehru and Gandhi about centralised planning and state-led industrialisation versus agrarian populism. 6. Even today, the west Delhi parliamentary constituency of Karol Bagh is reserved for Scheduled Caste candidates since they continue to be numerically signicant in this area. 7. Gandhis election as a Member of Parliament had been overturned by the Allahabad High Court on grounds of procedural irregularities, and her government faced a rising tide of opposition from the labour and student movements. 8. After a period of exile when the Congress was thrown out of power at the end of the Emergency, Jagmohans political career revived with his appointment as Governor of Jammu and Kashmir during the height of insurgency in that state. He changed sides and, having joined the BJP, was appointed Union Minister for Urban Development, from which position he continued the urban cleansing projects that he had initiated during the Emergency. It was during Jagmohans tenure that the judicial orders about closing down industries and relocating slums were vigorously pursued. While he gained the applause of the bourgeoisie, BJP politicians in Delhi who were concerned about the fallout from Jagmohans zeal on their electoral fortunes succeeded in getting him transferred from the Urban Development ministry in September 2001. 9. They have been constrained by the highly regulated nature of Delhis public spaces. For several years, no protest events have been

r UNESCO 2003.

98

Amita Baviskar

allowed within a certain radius of the Parliament and in parts of the city where they can actually intrude on public consciousness.

Incarcerated within permitted venues such as the grounds behind the Red Fort, massed bodies of protestors have limited impact in

terms of making their cause visible and audible.

References

ALONSO, A. M. 1994. The politics of space, time and substance: state formation, nationalism and ethnicity, Annual Review of Anthropology 23, 379405. APPADURAI, A. 1993. Number in the colonial imagination, in Breckenridge, C., and van der Veer, P. (eds). Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. BAVISKAR, A. 2001. Written on the body, written on the land: violence and environmental struggles in central India, in Peluso, N., and Watts, M. (eds). Violent Environments. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 354379. BOURDIEU, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DAS, V. 1995. Critical Events: An Anthropological Perspective on Contemporary India. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ESCOBAR, A. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. GEDDES, P. 1915. Cities in Evolution: An Introduction to the Town Planning Movement and to the Study of Civics. London: Williams and Norgate. GUPTA, N. 1981. Delhi Between Two Empires, 18031930: Society, Government and Urban Growth. Delhi: Oxford University Press. KHILNANI, S. 1997. The Idea of India. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. LI, T. M. 1999. Compromising power: development, culture, and rule in Indonesia, Cultural Anthropology 14(3), 295322. LUDDEN, D. 1992. Indias development regime, in Dirks, N. B. (ed.), Colonialism and Culture. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. MALKKI, L. 1992. National geographic: the rooting of peoples and the territorialisation of national identity among scholars and refugees, Cultural Anthropology 7(1), 2444. MOORE, D. 1998. Subaltern struggles and the politics of place: remapping resistance in Zimbabwes eastern highlands, Cultural Anthropology 13(3), 344381. PUDR (PEOPLES UNION FOR DEMOCRATIC RIGHTS) 1995. A Tale of Two Cities: Custodial Death and Police Firing in Ashok Vihar, April. RAVINDRAN, K. T. 2000. A state of siege, in Frontline, December 22, 116118. SAAJHA MANCH 2000. Some Issues Concerning an Alternative Plan for Delhi, unpublished report, Delhi, July. SAAJHA MANCH 2001. Manual for Peoples Planning: A View from Below of Problems of Urban Existence in Delhi, unpublished report, Delhi, March. SCOTT, J. C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. SUNDAR, N. 2001. Beyond the bounds? Violence at the margins of new legal geographies, in Peluso, N., and Watts, M. (eds), Violent Environments. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. TARLO, E. 2002. Unsettling Memories: Narratives of the Emergency in India. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

r UNESCO 2003.

Вам также может понравиться

- Industrial Revolution and Town PlanningДокумент24 страницыIndustrial Revolution and Town PlanningAnupamaTirkey33% (3)

- Short - Essay - On - Fendi Porter's Five ForcesДокумент6 страницShort - Essay - On - Fendi Porter's Five ForcesayaandarОценок пока нет

- ChandigarhДокумент4 страницыChandigarhmozaster100% (1)

- Banashree Urban VillagesДокумент17 страницBanashree Urban VillagesBanashree BanerjeeОценок пока нет

- Emma Tarlo Unsettling Memories Narratives of The Emergency in DelhiДокумент11 страницEmma Tarlo Unsettling Memories Narratives of The Emergency in DelhiAnushka KelkarОценок пока нет

- Upper-Intermediate Fame & Celebrity VocabularyДокумент1 страницаUpper-Intermediate Fame & Celebrity VocabularybestatemanОценок пока нет

- BAVISKAR. Between Violence and DesireДокумент10 страницBAVISKAR. Between Violence and DesireJessicaLorranyОценок пока нет

- Between Violence and Desire: Space, Power, and Identity in The Making of Metropolitan DelhiДокумент10 страницBetween Violence and Desire: Space, Power, and Identity in The Making of Metropolitan DelhiSiddharthОценок пока нет

- BaviskardelhidisplacementДокумент11 страницBaviskardelhidisplacementAna Clara VianaОценок пока нет

- Shahjahanabad: Old DelhiДокумент43 страницыShahjahanabad: Old Delhib570793100% (7)

- Conservation 1Документ10 страницConservation 1rahulsankavarmaОценок пока нет

- Running Head: Art Blurring Boundaries 1Документ10 страницRunning Head: Art Blurring Boundaries 1Samvida11Оценок пока нет

- Bhan ThisisNottheCityIOnceKnew PDFДокумент16 страницBhan ThisisNottheCityIOnceKnew PDFSafina AzeemОценок пока нет

- NISHANT Dissertation 05NOVupdateДокумент31 страницаNISHANT Dissertation 05NOVupdateNishant ChhatwalОценок пока нет

- Exploring The Indus Valley Civilization in India: ArticleДокумент55 страницExploring The Indus Valley Civilization in India: Articleaparna joshiОценок пока нет

- 2019 08 15 - Assignment 02Документ4 страницы2019 08 15 - Assignment 02Nishigandha RaiОценок пока нет

- Entangeled Urbanism CompilationДокумент15 страницEntangeled Urbanism CompilationSowmyaОценок пока нет

- Urban PlanningДокумент33 страницыUrban Planningpatel krishnaОценок пока нет

- CBSE Class 12 Sociology Social Change and Development in India Revision Notes Chapter 1Документ5 страницCBSE Class 12 Sociology Social Change and Development in India Revision Notes Chapter 1Ayesha NadeemОценок пока нет

- Welcome Surprises 24.04.06 StraightenedДокумент10 страницWelcome Surprises 24.04.06 Straightenedgammi123Оценок пока нет

- Making and Unmaking of ChandigarhДокумент5 страницMaking and Unmaking of Chandigarhmanpreet kaurОценок пока нет

- Delhi Master Plan 1962 AnalysisДокумент19 страницDelhi Master Plan 1962 AnalysisShravan Kumar75% (4)

- Heritage Conservation in Ahmadabad PDFДокумент35 страницHeritage Conservation in Ahmadabad PDFSiddhi VashiОценок пока нет

- 05 Partho Datta GeddesДокумент26 страниц05 Partho Datta GeddesShireen MirzaОценок пока нет

- CBSE Class 12 Sociology Revision Notes Chapter-1 Structural ChangeДокумент5 страницCBSE Class 12 Sociology Revision Notes Chapter-1 Structural ChangeZainab KhanОценок пока нет

- UrbTop 149172-Layout1Документ11 страницUrbTop 149172-Layout1Daniel Dent MurguiОценок пока нет

- A Mass of Anomalies Land Law and Sovereignty in An Indian Company TownComparative Studies in Society and HistoryДокумент23 страницыA Mass of Anomalies Land Law and Sovereignty in An Indian Company TownComparative Studies in Society and HistoryArqacОценок пока нет

- Paper 16, Module 27, ETextДокумент19 страницPaper 16, Module 27, ETextmalticОценок пока нет

- UNIT V Architectural ConservationДокумент13 страницUNIT V Architectural ConservationsruthiОценок пока нет

- Aphg Chapter 9Документ20 страницAphg Chapter 9Derrick Chung100% (1)

- Urban Regeneration and Preservation of B PDFДокумент8 страницUrban Regeneration and Preservation of B PDFdidarulОценок пока нет

- Urban Formation and Cultural Transformation in Mughal India: Rukhsana IftikharДокумент9 страницUrban Formation and Cultural Transformation in Mughal India: Rukhsana IftikharSharandeep SandhuОценок пока нет

- Delhi Margins ArticleДокумент16 страницDelhi Margins Articlepinkish zahraОценок пока нет

- Urban Design Methods and TechniquesДокумент9 страницUrban Design Methods and TechniquesShraddha BahiratОценок пока нет

- Ruled by Records:: The Expropriation of Land and The Misappropriation of Lists in IslamabadДокумент18 страницRuled by Records:: The Expropriation of Land and The Misappropriation of Lists in IslamabadLaura Garcia RincónОценок пока нет

- Land As The Key To Urban Development: Housing in Indonesian Cities, 1930-1960Документ1 страницаLand As The Key To Urban Development: Housing in Indonesian Cities, 1930-1960Dian KusbandiahОценок пока нет

- HistoryДокумент6 страницHistoryThe ArtistОценок пока нет

- Evaluation of City As PhenomenalДокумент7 страницEvaluation of City As Phenomenalsuthar99sureshОценок пока нет

- Nation and Village - Images of Rural India in Gandhi, Nehru and AmbedkarДокумент12 страницNation and Village - Images of Rural India in Gandhi, Nehru and AmbedkarBinithaОценок пока нет

- Ranjan2017 Article UnravelingTheNarrativesOfAdivaДокумент9 страницRanjan2017 Article UnravelingTheNarrativesOfAdivaLakshmi SachidanandanОценок пока нет

- PublicSpace Reader PG NewДокумент35 страницPublicSpace Reader PG Newnaveen prasadОценок пока нет

- An Social Structures: Written By: Anand Jha (2005 Jds 6006) Guided By: DR - Ravinder KaurДокумент9 страницAn Social Structures: Written By: Anand Jha (2005 Jds 6006) Guided By: DR - Ravinder KauryayavarОценок пока нет

- Erasing The Edifices of National Importance-The Much Needed Task of The Hour?Документ8 страницErasing The Edifices of National Importance-The Much Needed Task of The Hour?Sai KamalaОценок пока нет

- The Politics of Commemoration in Delhi After The Indian Rebellion of 1857 Has Been A Subject of Significant Historiographical InquiryДокумент9 страницThe Politics of Commemoration in Delhi After The Indian Rebellion of 1857 Has Been A Subject of Significant Historiographical InquiryJestee JainОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2Документ31 страницаChapter 2kanad kumbharОценок пока нет

- Urban Formation and Cultural Transformation in Mughal India: Rukhsana IftikharДокумент9 страницUrban Formation and Cultural Transformation in Mughal India: Rukhsana Iftikharpriyam royОценок пока нет

- Each City Had Well-Planned Architecture, Public Granaries and Efficient Sewage and Drainage SystemДокумент5 страницEach City Had Well-Planned Architecture, Public Granaries and Efficient Sewage and Drainage SystemSatyamShuklaОценок пока нет

- Awadhendra Sharan - in The City, Out of PlaceДокумент7 страницAwadhendra Sharan - in The City, Out of PlaceAlankarОценок пока нет

- Relevance of World Civilizations To Third World CountriesДокумент11 страницRelevance of World Civilizations To Third World CountriesCedo CeddОценок пока нет

- ECC 2013 ARCH312 FinalPaper FinalДокумент12 страницECC 2013 ARCH312 FinalPaper FinalLaura Wake-RamosОценок пока нет

- Harold HДокумент6 страницHarold HritaОценок пока нет

- Unit-8 Ancient, Medieval and ColonialДокумент10 страницUnit-8 Ancient, Medieval and Colonialanuj dhuppadОценок пока нет

- Urban Villages Under Chinas Rapid UrbanizationДокумент10 страницUrban Villages Under Chinas Rapid Urbanizationf1219417Оценок пока нет

- 10.4324 9781315735825-8 ChapterpdfДокумент14 страниц10.4324 9781315735825-8 Chapterpdf03 Akshatha NarayanОценок пока нет

- Soc Final PDFДокумент7 страницSoc Final PDFTabassum FarihaОценок пока нет

- Town Planning, Public Health And-Urban Poor-Some Explorations From Delhi, Ritupriya EPW, Apr 24, 1993Документ11 страницTown Planning, Public Health And-Urban Poor-Some Explorations From Delhi, Ritupriya EPW, Apr 24, 1993ANIKET SHINDEОценок пока нет

- Chapter-3-The Struggle BeginsДокумент10 страницChapter-3-The Struggle BeginsSamrat MisraОценок пока нет

- Subjects of Heritage in Urban Southern India PDFДокумент25 страницSubjects of Heritage in Urban Southern India PDFNatasha KhaitanОценок пока нет

- The Indian HistoryДокумент16 страницThe Indian HistoryTouseef ShopianОценок пока нет

- Welcome to the Urban Revolution: How Cities Are Changing the WorldОт EverandWelcome to the Urban Revolution: How Cities Are Changing the WorldРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (7)

- India Abroad: Diasporic Cultures of Postwar America and EnglandОт EverandIndia Abroad: Diasporic Cultures of Postwar America and EnglandРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Interview To Quingyun MaДокумент6 страницInterview To Quingyun Madpr-barcelonaОценок пока нет

- Language and DefinitionДокумент9 страницLanguage and DefinitionBalveer GodaraОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of Syntax and Academic Word Choice in Political NewsДокумент30 страницAn Analysis of Syntax and Academic Word Choice in Political NewsTiffany SpenceОценок пока нет

- MG 302 Asgnt 4 - 25% Litreature Review - Marking Rubric - Replaces Final ExamДокумент2 страницыMG 302 Asgnt 4 - 25% Litreature Review - Marking Rubric - Replaces Final ExamArtika DeviОценок пока нет

- History of KeerthanaigalДокумент8 страницHistory of KeerthanaigalJeba ChristoОценок пока нет

- RC Academic Info PDFДокумент217 страницRC Academic Info PDFRishab AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Theology ReviewerДокумент3 страницыTheology ReviewerAndrea CawaОценок пока нет

- CBT OrientationДокумент46 страницCBT OrientationSamantha SaundersОценок пока нет

- The Contribution of Guido of Arezzo To Western Music TheoryДокумент6 страницThe Contribution of Guido of Arezzo To Western Music TheoryPeter JoyceОценок пока нет

- Matisse Drawings PDFДокумент321 страницаMatisse Drawings PDFPatricio Aros0% (1)

- Memorandum of Agreement: RD THДокумент3 страницыMemorandum of Agreement: RD THDaneen GastarОценок пока нет

- Philosophy of Education PrelimДокумент31 страницаPhilosophy of Education PrelimDana AquinoОценок пока нет

- Randall Collins TheoryДокумент11 страницRandall Collins TheoryEmile WeberОценок пока нет

- Imam PositionДокумент5 страницImam PositionAzharulHind0% (1)

- Miller, Ivor. Cuban Abakuá Chants. Examining New Linguistic and Historical Evidence For The AfricanДокумент37 страницMiller, Ivor. Cuban Abakuá Chants. Examining New Linguistic and Historical Evidence For The Africanjacoblrusso100% (1)

- NOTA: Leia As Instruções Em: Training, 46 (5)Документ2 страницыNOTA: Leia As Instruções Em: Training, 46 (5)Herculano RebordaoОценок пока нет

- Republic Act 11053 - New Anti Hazing LawДокумент9 страницRepublic Act 11053 - New Anti Hazing LawAnonymous WDEHEGxDhОценок пока нет

- Contempo Week 2Документ4 страницыContempo Week 2Regina Mae Narciso NazarenoОценок пока нет

- Measuring Media Effectiveness in BangladeshДокумент46 страницMeasuring Media Effectiveness in BangladeshOmar Sayed TanvirОценок пока нет

- The Implementation of Anti-Bullying Program To The Students Among Early Learners ofДокумент7 страницThe Implementation of Anti-Bullying Program To The Students Among Early Learners ofLyka Eam TabierosОценок пока нет

- Non Verbal CommunicationДокумент13 страницNon Verbal CommunicationAmalina NОценок пока нет

- REVIEWER - EthicsДокумент7 страницREVIEWER - EthicsMaria Catherine ConcrenioОценок пока нет

- The Glory of Africa Part 10Документ54 страницыThe Glory of Africa Part 10Timothy100% (1)

- Indonesian Students' Cross-Cultural Adaptation in Busan, KoreaДокумент13 страницIndonesian Students' Cross-Cultural Adaptation in Busan, KoreaTakasu ryuujiОценок пока нет

- Endhiran LyricsДокумент15 страницEndhiran LyricsVettry KumaranОценок пока нет

- The Concept of The Perfect Man in The Thought of Ibn Arabi and Muhammad Iqbal A Comparative StudyДокумент98 страницThe Concept of The Perfect Man in The Thought of Ibn Arabi and Muhammad Iqbal A Comparative StudyNiko Bellic83% (6)

- Synoposis AnishДокумент8 страницSynoposis AnishAnishОценок пока нет

- Mwinlaaru - PHD Thesis - FinalДокумент434 страницыMwinlaaru - PHD Thesis - FinalSamuel EkpoОценок пока нет