Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Studio7 Article Swim Lessons

Загружено:

MapychaИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Studio7 Article Swim Lessons

Загружено:

MapychaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Swim Lessons From the Worlds Best Swimmers

Article by Gale Bernhardt

It can be argued that few people know more about swimming than Jonty Skinner, director of performance science and technology for USA Swimming. Jonty spends a good deal of his time poring over swimming videos of the top swimmers in the world, analyzing every detail of every swim stroke. By utilizing underwater video in conjunction with the Dartfish software program, body position can be analyzed in great detail, including measuring specific angles. In a recent coaching clinic, Jonty talked about key swim technique issues in freestyle with video and data to back up his observations. I asked him to provide more detail about freestyle swimming analysis and how his pool observations relate to triathlon. Our discussion is summarized in this column, including photographs, courtesy of USA Swimming. The swimmer featured in the photographs is Kayln Keller. Kayln was on the Pan Am team in 1999 and won the 800 freestyle at the Goodwill Games in 2001. In 2002, her swimming was at a plateau and she struggled to keep the back half of her races strong. In the early summer of 2003, she changed to more of a catch-up, or front-quadrant (see Figure 1 for a location of the front quadrant), method of freestyle. In Jonty's opinion, this change paved the way to her three national titles in the summer of 2003 and was instrumental in her making the 2004 Olympic team.

Figure 1 In addition to changing to front-quadrant swimming, she changed her arm angle and the timing of her hip rotation. She went from a technique that was basically a straight (as viewed from the side) underwater pull with a hip rotation emphasis during the finish phase of the stroke, to a high elbow in the catch-anchor phase of the stroke, with the body roll occurring during the front quadrant of the stroke. This change is evident in the photographs included in this article.

Swim Lessons From the Worlds Best Swimmers

Article by Gale Bernhardt

Photo Set 1 Using Kayln as our model swimmer, let's look at six key areas that you might want to consider when evaluating in your own stroke. Breathing and head position The biggest problem in freestyle is created by the need to breathe. If we could just keep our heads down, freestyle could be much more efficient. Jonty noted that good head position is exasperated in the swimming pool by the environmental effect of swimmers looking up to see who's coming toward them, how far they are from the swimmer ahead, and the location of the wall. Picking the head up automatically drops the hips. In the top frame of Photo Set 1 (2002), Kayln's spine is slightly curved and her head has been lifted off of the horizontal plane to initiate a breath. Her neck is bent to breathe. Notice that her hips are minimally rotated. In the bottom frame of Photo Set 1 (2004) her head is almost an extension of her spine line, her neck is not craned upward, her spine is straighter and her hips are fully rotated to engage the anchor position of her right hand. This allows her to glide through the water creating the least amount of resistance drag. The distance that Kayln lifted her head up in the 2002 photo is minimal compared to the distance triathletes lift their heads to sight buoys during a race. Imagine how far your hips will sink when you use your direction-finder head lift in conjunction with a breath at the same time. Jonty suggested that instead of trying to breathe at the same time you're catching a glimpse of the next buoy, breathe first and then try to sight by only sneaking your eyes out of the water -- your nose and mouth remain underwater. I tried this in the pool and was amazed at how much less my hips sank. Additionally, the stress on my upper body muscles was much less than when I was trying to breathe and sight on a target -- getting my mouth out of the water. If you've been sighting and breathing at the same time, it will take practice to change the timing. Breathe first, take a stroke and then sight with only your eyes out of the water. Give it a try and see what you think.

Swim Lessons From the Worlds Best Swimmers

Article by Gale Bernhardt

It's hard enough for most swimmers to get breathing on a single side correct; biilateral breathing, or breathing on both sides of your stroke, is even more difficult for most swimmers. I'm often asked if triathletes should always aim to bilateral breathe. I think it's good to practice bilateral breathing in workouts so that you can sight to either side during a race. I think practicing bilateral breathing helps make the freestyle stroke more even and balanced. But, if you're faster and can swim with less energy expenditure by breathing to just one side during a race, do it. Jonty agreed, and his data on elite swimmers shows that some of them are slower in competition when breathing bilaterally. Even though there's the temptation to want to watch a competitor for every length of the race, by breathing on their non-preferential side there have been a number of cases in which these athletes have actually lost ground to their competitors.

Photo Set 2 Front-quadrant loading Some triathlon coaches instruct triathletes to "finish your stroke" with a strong push past the hip while the opposite arm is just entering the water. There are two issues with this instruction. First, the windmill-type approach to swimming in which your arms are always opposite of each other isn't efficient, puts stress on small shoulder muscles and doesn't produce fast swimming. Second, from watching elite swimmers, we know that the longer the race distance, the less finish force is included in the stroke. Look at Photo Set 2. The top photo was taken in 2002, the bottom photo in 2004. Both photographs were synchronized so the right hand is in the same spot. Notice in the 2004 photo how Kayln's left hand is entering the water while her right arm is in the catch, anchor phase. This is frontquadrant swimming. In the next article I'll cover body position, underwater arm position, tempo vs. distance per cycle, what pace to swim in your workouts and summarize with tips to improve.

In the first part of this article we started our swim lesson, led by Jonty Skinner, director of performance science and technology for USA Swimming. We learned about quadrant swimming, breathing and head position, and front-quadrant loading. This article continues to look at what triathletes can learn from the world's top swimmers.

Swim Lessons From the Worlds Best Swimmers

Article by Gale Bernhardt

Flat body position vs. a rotated body position Some of the beginning swimmers I see have been so focused on form drills and body rotation that they actually over rotate. However, Jonty sees more pool swimmers with a flat body position. Either extreme, flat body position or over rotation, produces sub-optimal results. What does a good rotation look like? Good rotation is a combination of angle and timing. Take another look at Photo Set 2 below. In the top frame (2002), Kayln's hips are rotated; but her head is lifted, causing her hips to fall farther below the water surface than the 2004 frame below. In the 2004 frame, her hips have already rotated toward her left side creating power through body roll. Think about a baseball player or a golfer trying to hit the ball using only his or her arms -- the potential power using arms alone is far less than what's possible when several muscle groups are used. This power generation is why swimmers should use the entire torso to initiate the freestyle stroke. Also notice in this photograph that Kayln's body is much higher in the water in the 2004 frame than in the 2002 frame. If she's positioned higher in the water, she uses less energy to propel herself. In triathlon, it's important to limit the energy expenditures in swimming in order to have enough energy to complete the remaining two events.

Photo Set 2 In order to get a better feeling of a high body position in the water, wear a wetsuit. Notice how easy it is to glide through the water when you're positioned higher? High elbow vs. straight arm pull underwater In Photo 2, the 2002 frame, Kayln's right elbow is low in the water and her arm has less bend than the 2004 frame. A high-elbow and bent-arm position is much more powerful than a straight-arm pull because you're engaging larger muscles and getting more leverage.

Swim Lessons From the Worlds Best Swimmers

Article by Gale Bernhardt

For example, try to get out of the pool without bending your arms to hoist yourself on deck. It's impossible. Now, get out of the pool the easiest way you can -- I bet your arms are bent. Of course, my example is exaggerated because your arm, hand and body positions aren't the same exiting the pool as they are in swimming, but I think it makes the point. Tempo vs. distance per cycle Swimming is similar to cycling and running in that there's an optimal cadence range for top athletes. For cycling, the optimal cadence is somewhere between 80 and 100 pedal revolutions per minute (rpm.) If the pedaling rpm is too low, the athlete is likely mashing the gears, causing greater stress on the knees and more muscular fatigue. At the same time, spinning the pedals at 120+ rpm is good for powerful track sprinters going relatively short distances; but doesn't work well for longer cycling events. World-class swimming cadence is typically 40 to 55 cycles per minute. A right-arm entry to the next right-arm entry equates to one cycle. Top women are on the higher end of the spectrum, and men are on the lower end. Because women aren't typically as strong as their male counterparts, they utilize higher cadences instead of strength to generate speed. For example, Janet Evans swims 55 cycles per minute and Brooke Bennett swims 53 to 54 cycles per minute. Grant Hackett is at 40 and Larsen Jensen is at 38 cycles per minute. In wavy, open-water conditions, Jonty notes that it's important for triathletes to keep cadence high -- particularly in windy, wavy water with chop. A swimmer with low turnover will be tossed around more than a swimmer with a higher turnover. Getting tossed around can potentially increase form drag and result in a higher metabolic cost. Other swimming articles I've read promote a certain number of strokes per 25 meters to be optimal for everyone. A one-size-fits-all approach to swimming cadence or a specific number of strokes per length of the pool is incorrect. For each athlete, strokes per length of the pool depends on where his or her center of mass is located, body composition, physiology, anthropomometry (measurements of body segments and the interrelationship of those measurements), the length and shape of the upper torso, the strength profile, leg power and feel for the water. Practice race-pace swimming Some beginning swimmers are so concerned with form drills that they don't swim enough laps at race pace. Drills are important and should be done with a specific purpose in mind, but during tough training and racing the metabolic cost is dictated by motor unit demand. If you go into a race demanding paces and body conditions that you haven't experienced in training, fatigue will be a problem during the last half of the swim, the bike and the run. Swimming fast with the least possible energy expenditure is the goal. How to improve Armed with information from the world's best swimmers, how do you apply this to your own swimming? If you have a chance to have your stroke videotaped above and below the water, take advantage of this great tool. Compare your stroke to the photographs in this article. Getting feedback on your stroke technique during swimming sessions from a knowledgeable coach is invaluable.

Swim Lessons From the Worlds Best Swimmers

Article by Gale Bernhardt

When you swim drills in the pool, do them with a specific purpose in mind: to improve your stroke in some manner. Don't be tempted to blast through the drills mindlessly just to get to the main set and "real swimming." Be aware of your body and what it's doing in the water. Establish a feel for the water. Do the majority of your high-intensity training at the cycle rates you intend to use during the swimming portion of your race. If possible, swim some workouts in conditions that simulate race day.

If world-class swimmers can make improvements to their strokes to improve speed or reduce energy costs, you can too -- no matter how long you've been swimming.

Gale Bernhardt was the 2003 USA Triathlon Pan American Games and 2004 USA Triathlon Olympic coach for both the men's and women's teams. Her first Olympic experience was as a personal cycling coach at the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games.

Вам также может понравиться

- Swimming Steps To SuccessДокумент240 страницSwimming Steps To SuccessMapychaОценок пока нет

- Swimming Steps To SuccessДокумент240 страницSwimming Steps To SuccessMapychaОценок пока нет

- Vegetable Gardening Encyclopedia PDFДокумент261 страницаVegetable Gardening Encyclopedia PDFMapycha100% (2)

- It's About: The Competitive Advantage of Quick Response ManufacturingДокумент8 страницIt's About: The Competitive Advantage of Quick Response ManufacturingMapychaОценок пока нет

- Science of Swimming FasterДокумент548 страницScience of Swimming FasterMapycha100% (4)

- Analyze Improve Control (AIC)Документ16 страницAnalyze Improve Control (AIC)Gajanan Shirke AuthorОценок пока нет

- 8 Minute Meditation Quiet Your Mind - Change Your Life PDFДокумент188 страниц8 Minute Meditation Quiet Your Mind - Change Your Life PDFClément HenrietОценок пока нет

- Scientific Greenhouse Gardening - ImagesДокумент73 страницыScientific Greenhouse Gardening - ImagesMapychaОценок пока нет

- The John Adair Handbook of Management and Leadership.Документ242 страницыThe John Adair Handbook of Management and Leadership.Mapycha100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Kawasaki KLX 300Документ5 страницKawasaki KLX 300klukasinteriaОценок пока нет

- Duke XC SL Race ServiceДокумент10 страницDuke XC SL Race ServicesilverapeОценок пока нет

- V2 en Notice Velo TILT 08 2012Документ22 страницыV2 en Notice Velo TILT 08 2012wirelesssoulОценок пока нет

- Paket 2 TO UN SMP Bahasa Inggris 2013Документ12 страницPaket 2 TO UN SMP Bahasa Inggris 2013DSSОценок пока нет

- Brochure Sport Uk 2008Документ10 страницBrochure Sport Uk 2008Kurniawan DoankОценок пока нет

- BmxstudentДокумент4 страницыBmxstudentapi-249283966100% (1)

- Suzuki RMX 250 Service ManualДокумент5 страницSuzuki RMX 250 Service ManualRodrigo VinhoОценок пока нет

- Zetrablade PDFДокумент1 страницаZetrablade PDFEcarroll41Оценок пока нет

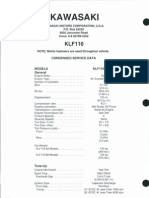

- 92 KLF110 Service SpecsДокумент12 страниц92 KLF110 Service Specs33scottОценок пока нет

- 2018 Enduro World Series Olargues ResultsДокумент31 страница2018 Enduro World Series Olargues ResultsAJ BarlasОценок пока нет

- Land RoverДокумент14 страницLand RoverSharan YadavОценок пока нет

- Adam Accessories BrochureДокумент9 страницAdam Accessories BrochurekarambaОценок пока нет

- Physical Work Capacity TestДокумент3 страницыPhysical Work Capacity TestSoya Asakura0% (1)

- Catalog Dia Compe 2016 2017Документ40 страницCatalog Dia Compe 2016 2017johnnyrossasОценок пока нет

- ATV Linhai ATV Service Manual PDFДокумент341 страницаATV Linhai ATV Service Manual PDFPanos Rousetis100% (1)

- Sports Medicine Specialists Rehabilitation ProtocolsДокумент59 страницSports Medicine Specialists Rehabilitation ProtocolsThe Homie100% (2)

- 2008 RST CatalogДокумент35 страниц2008 RST CatalogGoodBikesОценок пока нет

- Specialized Epic 2018 - Versioni UomoДокумент8 страницSpecialized Epic 2018 - Versioni UomoMTB-VCOОценок пока нет

- Suspension AirmaticДокумент83 страницыSuspension AirmaticAnonymous N4swcSОценок пока нет

- Yamaha RXZ135 2001 SP PDFДокумент25 страницYamaha RXZ135 2001 SP PDFEdward Hestin Ginjom100% (3)

- Last Herb 160 FrameДокумент2 страницыLast Herb 160 FramelastbikesОценок пока нет

- Ultimate A/T Sport A/T Exceed A/T Exceed M/T Gls M/T GLX M/TДокумент2 страницыUltimate A/T Sport A/T Exceed A/T Exceed M/T Gls M/T GLX M/TJoe DettОценок пока нет

- 2002 Black Owners ManualДокумент5 страниц2002 Black Owners ManualRodolfo BarrazaОценок пока нет

- 1986 GT CatalogДокумент16 страниц1986 GT CatalogtspinnerОценок пока нет

- Fiat 500 Pop 2013Документ26 страницFiat 500 Pop 2013ExtratenorОценок пока нет

- SUZUKI v-STROM 650-1000 - Touratech CatalogДокумент26 страницSUZUKI v-STROM 650-1000 - Touratech CatalogGraciolliОценок пока нет

- 006 Giant Bicycle - Contend SL 2 (2017)Документ1 страница006 Giant Bicycle - Contend SL 2 (2017)AnirbanОценок пока нет

- 058-071 GB 166 MonoДокумент14 страниц058-071 GB 166 Monobradu09Оценок пока нет

- Eg 163 Solidworks Assignment2Документ3 страницыEg 163 Solidworks Assignment2al3al3Оценок пока нет

- SRT 05 Feb 04Документ40 страницSRT 05 Feb 04akshay malik100% (2)