Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Natural Law Himma

Загружено:

Vanny Gimotea BaluyutАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Natural Law Himma

Загружено:

Vanny Gimotea BaluyutАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1 Natural Law (Himma) - refers to a type ofmoral theory, as well as to a type of legal theory, but the core claims

of the two kinds of theory are logically independent. -does not refer to the laws of nature, the laws that science aims to describe. NATURAL LAW MORAL THEORY - the moral standardsthat govern human behavior are, in some sense, objectively derived from the nature of human beings and the nature of the world. NATURAL LAW LEGAL THEORY - the authority of legal standards necessarily derives, at least in part, from considerations having to do with the MORAL MERIT of those standards. KINDS OF NATURAL LAW LEGAL THEORIES, differing from each other with respect to the role that morality plays in determining the authority of legal norms: CONCEPTUAL JURISPRUDENCE OF JOHN AUSTIN - provides a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of law that distinguishes law from non-law in every possible world. CLASSICAL NATURAL LAW THEORY - such as the theory of Thomas Aquinas focuses on the overlap between natural law moral and legal theories. (both a theory of law and an ethical theory) NEO-NATURALISM OF JOHN FINNIS - development of classical natural law theory. PROCEDURAL NATURALISM OF LON L. FULLER - a rejection of the conceptual naturalist idea that there are necessary substantive moral constraints on the content of law. Ronald DworkinsThird Theory - response and critique of legal positivism. 2 KINDS OF NATURAL LAW THEORY 1. Theory of morality (Natural Law Moral Theory) Characterized by following theses: a. moral propositions can be objectively true or false; oral propositions have what is sometimes called objective standing in the sense that such propositions are the bearers of objective truth-value. Strictly speaking, then, natural law moral theory is committed only to the objectivity of moral norms. b. standards of morality are in some sense derived from, or entailed by, the nature of the world and the nature of human beings. St. Thomas Aquinas, for example, identifies the rational nature of human beings as that which defines moral law: the rule and measure of human acts is the reason, which is the first principle of human acts. 2. Natural Law Theory Of Law -there is no clean division between the notion of law and the notion of morality. -there are at least some laws that depend for their authority not on some pre-existing human convention, but on the logical relationship in which they stand to moral standards. Some norms are authoritative in virtue of their moral content, even when there is no convention that makes moral merit a criterion of legal validity.

2 Overlap Thesis - concepts of law and morality intersect in some way. * many natural law moral theorists are also natural law legal theorists, but the two theories, strictly speaking, are logically independent. One can deny natural law theory of law but hold a natural law theory of morality (e.g. John Austin). CONCEPTUAL NATURALISM a. The Project of Conceptual Jurisprudence Objective of conceptual (or analytic) jurisprudence: provide an account of what distinguishes law as a system of norms from other systems of norms, such as ethical norms. To provide a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of law that distinguishes law from non-law in every possible world. John Austin describes the project: conceptual jurisprudence seeks the essence or nature which is common to all laws that are properly so called.Conceptual analysis of law remains an important, if controversial, project in contemporary legal theory. Conceptual theories of law have traditionally been characterized in terms of their posture towards the Overlap Thesis. Conceptual theories of law have traditionally been divided into two main categories: 1. those like natural law legal theory that affirm there is a conceptual relation between law and morality 2. and those like legal positivism that deny such a relation.

To clarify the role of conceptual analysis in law, Brian Bix (1995) distinguishes a number of different purposes that can beserved by conceptual claims: (1) to track linguistic usage; (2) to stipulate meanings; (3) to explain what is important or essential about a class ofobjects; and (4) to establish an evaluative test for the concept. -Bix takes conceptual analysis in law to be primarily concerned with (3) and (4). b. CLASSICAL NATURAL LAW THEORY All forms of natural law theory subscribe to the Overlap Thesis. Notion of law cannot be fully articulated without some reference to moral notions.Strongest construction of the Overlap Thesis forms the foundation for the classical naturalism of Aquinas and Blackstone. Aquinas distinguishes four kinds of law: (1) eternal law; (2) natural law; (3) human law; and (4) divine law. Eternal law is comprised of those laws that govern the nature of an eternal universe (scientific (physical, chemical, biological, psychological, etc., laws by which the universe is ordered). Divine law is concerned with those standards that must be satisfied by a human being to achieve eternal salvation. One cannot discover divine law by natural reason alone; the precepts of divine law are disclosed only through divine revelation.

3 Natural Law is comprised of those precepts of the eternal law that govern the behavior of beings possessing reason and free will.First precept of the natural law, according to Aquinas, is the somewhat vacuous imperative to do good and avoid evil. AQUINAS IS ALSO A NATURAL LAW LEGAL THEORIST. a human law (that is, that which is promulgated by human beings) is valid only insofar as its content conforms to the content of the natural law Human law has just so much of the nature of law as is derived from the law of nature. But if in any point it deflects from the law of nature, it is no longer a law but a perversion of law.

The idea that a norm that does not conform to the natural law cannot be legally valid is the defining thesis of conceptual naturalism. Blackstone articulates the two claims that constitute the theoretical core of conceptual naturalism: 1) there can be no legally valid standards that conflict with the natural law; and 2) all valid laws derive what force and authority they have from the natural law. Classical naturalism is consistent with allowing a substantial role to human beings in the manufacture of law.

While the classical naturalist seems committed to the claim that the law necessarily incorporates all moral principles, this claim does not imply that the law is exhausted by the set of moral principles. The classical naturalist does not deny that human beings have considerable discretion in creating natural law. Rather she claims only that such discretion is necessarily limited by moral norms: legal norms that are promulgated by human beings are valid only if they are consistent with morality .

Critics of conceptual naturalism - unjust laws are all-too- frequently enforced against persons. -to say that human laws which conflict with the Divine law are not binding, that is to say, are not laws, is to talk stark nonsense (Austin) -conceptual naturalism undermines the possibility of moral criticism of the law; inasmuch as conformity with natural law is a necessary condition for legal validity, all valid law is, by definition, morally just. Problem with this line of objection: First, conceptual naturalism does not foreclose criticism of those norms that are being enforced by a society as law. Second, and more importantly, this line of objection seeks to criticize a conceptual theory of law by pointing to its practical implications a strategy that seems to commit a category mistake.The project motivating conceptual jurisprudence, then, is to articulate the concept of law in a way that accounts for these pre-existing social practices. A conceptual theory of law can legitimately be criticized for its failure to adequately account for the pre-existing data, as it were; but it cannot legitimately be criticized for either its normative quality or its practical implications.

A more interesting line of argument has recently been taken up by Brian Bix (1996). Following John Finnis (1980), Bix rejects the interpretation of Aquinas and Blackstone as conceptual naturalists, arguing instead that the claim that an unjust law is not a law should not be taken literally.

3. The Substantive Neo-Naturalism of John Finnis -naturalism of Aquinas and Blackstone should not be construed as a conceptual account of the existence conditions for law. -the classical naturalists were not concerned with giving a conceptual account of legal validity; rather they were concerned with explaining the moral force of law - The essential function of law is to provide a justification for state coercion. - an unjust law can be legally valid, but cannot provide an adequate justification for use of the state coercive power and is hence not obligatory in the fullest sense. So an unjust law fails to realize the moral ideals implicit in the concept of law. Ergo: unjust law is legally binding, but is not fully law. Finniss naturalism is both an ethical theory and a theory of law. VALUABLE BASIC GOODS: life, health, knowledge, play, friendship, religion, and aesthetic experience. Basic goods has intrinsic value in the sense that it should, given human nature, be valued for its own sake and not merely for the sake of some other good it can assist in bringing about. universal in the sense that it governs all human cultures at all times.

CONCEPTUAL POINT OF LAW IS TO FACILITATE THE COMMON GOOD by providing authoritative rules that solve coordination problems that arise in connection with the common pursuit of these basic goods. Finnis takes care to deny that there is any necessary moral test for legal validity. However, Finnis believes that to the extent that a norm fails to satisfy these conditions, it likewise fails to fully manifest the nature of law and thereby fails to fully obligate the citizen-subject of the law. Unjust laws may obligate in a technical legal sense, on Finniss view, but they may fail to provide moral reasons for action of the sort that it is the point of legal authority to provide.

4. Procedural Naturalism of Lon Fuller -rejects the conceptual naturalist idea that there are necessary substantive moral constraints on the content of law. - believes that law is necessarily subject to a procedural morality. - human activity is necessarily goal-oriented or purposive in the sense that people engage in a particular activity because it helps them to achieve some end. - particular human activities can be understood only in terms that make reference to their purposes and ends. Thus, since lawmaking is essentially purposive activity, it can be understood only in terms that explicitly acknowledge its essential values and purposes.

5 Law is the enterprise of subjecting human conduct to the governance of rules. Unlike most modern theories of law, this view treats law as an activity and regards a legal system as the product of a sustained purposive effort. Laws essential function is to achieve social order through subjecting peoples conduct to the guidance of general rules by which they may themselves orient their behavior. -On Fullers view, law is necessarily subject to a procedural morality consisting of eight principles : P1: the rules must be expressed in general terms; P2: the rules must be publicly promulgated; P3: the rules must be prospective in effect; P4: the rules must be expressed in understandable terms; P5: the rules must be consistent with one another; P6: the rules must not require conduct beyond the powers of the affected parties; P7: the rules must not be changed so frequently that the subject cannot rely on them; and P8: the rules must be administered in a manner consistent with their wording. - no system of rules that fails minimally to satisfy these principles of legality can achieve laws essential purpose of achieving social order through the use of rules that guide behavior. - 8 principles are internal to law in the sense that they are built into the existence conditions for law. - A total failure in any one of these eight directions does not simply result in a bad system of law; it results in something that is not properly called a legal system at all. Fuller concludes that his eight principles are internal to law in the sense that they are built into the existence conditions for law. Fuller views morality as providing a constraint on the existence of a legal system: A total failure in any one of these eight directions does not simply result in a bad system of law; it results in something that is not properly called a legal system at all. Critic of Fullers view Hart: all actions, including virtuous acts like lawmaking and impermissible acts like poisoning, have their own internal standards of efficacy. Insofar as such standards of efficacy conflict with morality, as they do in the case of poisoning, it follows that they are distinct from moral standards. While Hart concedes that something like Fullers eight principles are built into the existence conditions for law, he concludes they do not constitute a conceptual connection between law and morality. FULLERS PRINCIPLES OPERATE INTERNALLY, NOT AS MORAL IDEALS, BUT MERELY AS PRINCIPLES OF EFFICACY.

5. Dworkins Third Theory - response to legal positivism, which is essentially constituted by three theoretical commitments: the Social Fact Thesis, the Conventionality Thesis, and the Separability Thesis.

6 Dworkin rejects positivisms Social Fact Thesis on the ground that there are some legal standards the authority of which cannot be explained in terms of social facts. In deciding hard cases, for example, judges often invoke moral principles that Dworkin believes do not derive their legal authority from the social criteria of legality contained in a rule of recognition. In Riggs v. Palmer, for example, the court considered the question of whether a murderer could take under the will of his victim. At the time the case was decided, neither the statutes nor the case law governing wills expressly prohibited a murderer from taking under his victims will. Despite this, the court declined to award the defendant his gift under the will on the ground that it would be wrong to allow him to profit from such a grievous wrong. On Dworkins view, the court decided the case by citing the principle that no man may profit from his own wrong as a background standard against which to read the statute of wills and in this way justified a new interpretation of that statute . TheRiggs court was not just reaching beyond the law to extralegal standards when it considered this principle. For the Riggs judges would rightfully have been criticized had they failed to consider this principle; if it were merely an extralegal standard, there would be no rightful grounds to criticize a failure to consider it. Dworkin concludes that the best explanation for the propriety of such criticism is that principles are part of the law. A moral principle is legally authoritative, according to Dworkin, insofar as it maximally conduces to the best moral justification for a societys legal practices considered as a whole. Dworkin believes that a legal principle maximally contributes to such a justification if and only if it satisfies two conditions: (1) the principle coheres with existing legal materials; and (2) the principle is the most morally attractive standard that satisfies. The correct legal principle is the one that makes the law the moral best it can be. Two elements of a successful interpretation: 1. interpretation must fit with those practices in the sense that it coheres with existing legal materials defining the practices. 2. since an interpretation provides a moral justification for those practices, it must present them in the best possible moral light. Thejudge must approach judicial decision-making as something that resembles an exercise in moral philosophy. Any judges opinion is itself a piece of legal philosophy, even when the philosophy is hidden and the visible argument is dominated by citation and lists of facts. THEORY OF JUDICIAL OBLIGATIONis a consequence of what he calls the Rights Thesis. Right Thesis - judicial decisions always enforce pre-existing rights. While the legislature may legitimately enact laws that are justified by arguments of policy, courts may not pursue such arguments in deciding cases. An appeal to a pre-existing right, according to Dworkin, can ultimately be justified only by an argument of principle. Thus, insofar as judicial decisions necessarily adjudicate claims of right, they must ultimately be based on the moral principles that figure into the best justification of the legal practices considered as a whole.

Вам также может понравиться

- Study Guide For Spanish 1 Spring Final Exam 1Документ4 страницыStudy Guide For Spanish 1 Spring Final Exam 1Michael You100% (2)

- Differentiating Instruction in The PrimaДокумент168 страницDifferentiating Instruction in The Primaapi-317510653Оценок пока нет

- Models of Teaching PDFДокумент478 страницModels of Teaching PDFbelford1186% (22)

- CRM For Cabin CrewДокумент15 страницCRM For Cabin CrewCristian Ciobanu100% (1)

- Jurisprudence Notes Ronald Dworkin'S InterpretivismДокумент40 страницJurisprudence Notes Ronald Dworkin'S Interpretivismdynamo vjОценок пока нет

- Ex Post Facto LawДокумент18 страницEx Post Facto LawJomar Ababa DenilaОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx On LawДокумент5 страницKarl Marx On LawWorkaholicОценок пока нет

- Legal Environment & Court SystemДокумент33 страницыLegal Environment & Court SystemDineshОценок пока нет

- Legal Positivism and Natural Law TheoryДокумент3 страницыLegal Positivism and Natural Law TheoryAngeliki EvripidouОценок пока нет

- Law and JusticeДокумент4 страницыLaw and JusticePrarthana GuptaОценок пока нет

- Nature and Scope of Administrative LawДокумент13 страницNature and Scope of Administrative LawSimar Bhalla100% (1)

- Bangalore Principles of Judicial ConductДокумент17 страницBangalore Principles of Judicial ConductmzzzzmОценок пока нет

- Juris New 2022Документ21 страницаJuris New 2022Deepti UikeyОценок пока нет

- CONSTITUTIONALISMДокумент8 страницCONSTITUTIONALISMAnkita SinghОценок пока нет

- Rule of LawДокумент21 страницаRule of LawMehak SinglaОценок пока нет

- Austin'S Theory of Laws As Command of The Sovereign: Evidence ActДокумент5 страницAustin'S Theory of Laws As Command of The Sovereign: Evidence ActHamzaОценок пока нет

- English4 Q4 Week 1Документ6 страницEnglish4 Q4 Week 1Caryll BaylonОценок пока нет

- 1954 The Science of Learning and The Art of TeachingДокумент11 страниц1954 The Science of Learning and The Art of Teachingcengizdemirsoy100% (1)

- Maria Mencia From Visual Poetry To Digital ArtДокумент149 страницMaria Mencia From Visual Poetry To Digital ArtChristina GrammatikopoulouОценок пока нет

- Module 1Документ54 страницыModule 1Estrelita Pajo RefuerzoОценок пока нет

- Theories of Law: Prepared By: MDM Namirah Mohd AkahsahДокумент39 страницTheories of Law: Prepared By: MDM Namirah Mohd AkahsahUmar MahfuzОценок пока нет

- Hohfeld's TheoryДокумент11 страницHohfeld's TheoryrahulsmankameОценок пока нет

- Some Aspects of Aristotle's Theory of SlaveryДокумент4 страницыSome Aspects of Aristotle's Theory of Slaveryilovemondays1Оценок пока нет

- ResiduaryДокумент34 страницыResiduarySatish BabuОценок пока нет

- National Law Institute University, BhopalДокумент18 страницNational Law Institute University, BhopalDurgesh yadavОценок пока нет

- Analytical SchoolДокумент28 страницAnalytical SchoolKashish TanwarОценок пока нет

- Customary LawДокумент3 страницыCustomary LawMalik Kaleem AwanОценок пока нет

- The Roman Slave Law in CourtДокумент3 страницыThe Roman Slave Law in CourturbnanthonyОценок пока нет

- L O A 1 InternalДокумент11 страницL O A 1 InternalpranjalОценок пока нет

- Structures of GovernmentДокумент2 страницыStructures of GovernmentOsama JamshedОценок пока нет

- Locke Theory of PropertyДокумент22 страницыLocke Theory of PropertyPhilem Ibosana Singh100% (1)

- Feminist JurisprudenceДокумент19 страницFeminist JurisprudenceDHIRENDRA KumarОценок пока нет

- Residuary Power of The UnionДокумент11 страницResiduary Power of The UnionSatish BabuОценок пока нет

- Austin's Theory of LawДокумент6 страницAustin's Theory of LawEsha JavedОценок пока нет

- Bodhisattwa Jurisprudence SynopsisДокумент6 страницBodhisattwa Jurisprudence SynopsisB MОценок пока нет

- Law of PropertyДокумент6 страницLaw of PropertyHuraeen Jannat RuhiОценок пока нет

- ConclusionДокумент3 страницыConclusionAli SchehzadОценок пока нет

- Hobbes, Bentham & AustinДокумент5 страницHobbes, Bentham & Austindark stallionОценок пока нет

- Separation of Powers and Check and Balance in Nepalese ContextДокумент6 страницSeparation of Powers and Check and Balance in Nepalese ContextArgus Eyed100% (1)

- Separation of Powers, Comparison of ConstitutionsДокумент5 страницSeparation of Powers, Comparison of ConstitutionsSrinivas JupalliОценок пока нет

- MSOP Project ReportДокумент3 страницыMSOP Project Reportcsankitkhandal0% (2)

- rights:: I. According To PhilosphersДокумент10 страницrights:: I. According To PhilosphersBilawal MughalОценок пока нет

- Jurisprudence & Legal Theory... Lec 1Документ31 страницаJurisprudence & Legal Theory... Lec 1Rahul TomarОценок пока нет

- Analytical Fair ProjectДокумент15 страницAnalytical Fair ProjectSyed Imran AdvОценок пока нет

- Civil Law: Assignment by DR Ramsha Rashid PTДокумент6 страницCivil Law: Assignment by DR Ramsha Rashid PTDr Ramsha BalochОценок пока нет

- Constitutionalism MeaningДокумент12 страницConstitutionalism MeaningSARIKAОценок пока нет

- TOPIC 4 (Subject of International Law)Документ9 страницTOPIC 4 (Subject of International Law)Putry Sara RamliОценок пока нет

- Divine Origin of StateДокумент2 страницыDivine Origin of StateAlisha KalraОценок пока нет

- Justice and Justice According To LawДокумент3 страницыJustice and Justice According To LawAdhishPrasadОценок пока нет

- Analytical SchoolДокумент28 страницAnalytical SchoolIstuvi SonkarОценок пока нет

- Political Science ProjectДокумент18 страницPolitical Science ProjectAshutosh KumarОценок пока нет

- The Doctrine of Harmonious Law Constitutional Administrative EssayДокумент5 страницThe Doctrine of Harmonious Law Constitutional Administrative EssayBhawna PalОценок пока нет

- A Master of English ProseДокумент7 страницA Master of English ProseVanshikaОценок пока нет

- Rule of Law Under Indian PerspectiveДокумент16 страницRule of Law Under Indian PerspectiveAadityaVasuОценок пока нет

- Gmail - Jurisprudence Notes - Concept of LawДокумент7 страницGmail - Jurisprudence Notes - Concept of LawShivam MishraОценок пока нет

- Public LawДокумент2 страницыPublic LawAsh D. AGОценок пока нет

- Slavery and Its Definition Allain - Bales PDFДокумент16 страницSlavery and Its Definition Allain - Bales PDFTanja MilojevićОценок пока нет

- Literature Review Law and MoralityДокумент4 страницыLiterature Review Law and MoralityAmit Singh100% (1)

- JP Yadav PRJCTДокумент12 страницJP Yadav PRJCTAshish VishnoiОценок пока нет

- Social Contract Theory 2Документ2 страницыSocial Contract Theory 2Amandeep Singh0% (1)

- Uniform Civil CodeДокумент5 страницUniform Civil Coderaveesh kumarОценок пока нет

- Rudolf Von Jhering - or Law As A Means To An EndДокумент20 страницRudolf Von Jhering - or Law As A Means To An EndMin H. GuОценок пока нет

- AcknowledgementДокумент17 страницAcknowledgementsumitkumar_sumanОценок пока нет

- Legal PersonДокумент15 страницLegal PersonSujit KumarОценок пока нет

- Dharma JurisprudenceДокумент9 страницDharma JurisprudenceKirtivaan mishraОценок пока нет

- Sources of LawДокумент28 страницSources of LawLalit SainiОценок пока нет

- BenthamДокумент7 страницBenthamNimya RoyОценок пока нет

- English 4 Quarter 4 Week 4 - Working Cooperatively and Responsibly - 2Документ18 страницEnglish 4 Quarter 4 Week 4 - Working Cooperatively and Responsibly - 2Vanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Super Christmas CarolДокумент1 страницаSuper Christmas CarolVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Jayme C. Uy, Et Al. v. Court of Appeals, Et Al. - G.R. No. 109197 June 21, 2001Документ8 страницJayme C. Uy, Et Al. v. Court of Appeals, Et Al. - G.R. No. 109197 June 21, 2001Vanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- PPCity Revenue Generation ProgramДокумент12 страницPPCity Revenue Generation ProgramVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- 10 4 3 l1Документ11 страниц10 4 3 l1Vanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Soil Pressure Foundation Shear: Bearing Capacity Is The Capacity ofДокумент1 страницаSoil Pressure Foundation Shear: Bearing Capacity Is The Capacity ofVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Walk AlatorДокумент11 страницWalk AlatorVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Financial Component: A. Financial Bid FormДокумент1 страницаFinancial Component: A. Financial Bid FormVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- City Assessor'S Office Organizational ChartДокумент1 страницаCity Assessor'S Office Organizational ChartVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Theory of Structure: Baluyut, Chiara Jayne GДокумент1 страницаTheory of Structure: Baluyut, Chiara Jayne GVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Mayors PermitДокумент1 страницаMayors PermitVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Strategic Initiatives, Sample: Initiative DescriptionДокумент2 страницыStrategic Initiatives, Sample: Initiative DescriptionVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

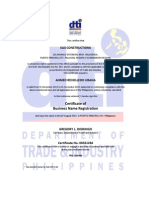

- Ea3 Constructions: Certificate of Business Name RegistrationДокумент1 страницаEa3 Constructions: Certificate of Business Name RegistrationVanny Gimotea BaluyutОценок пока нет

- Chapter 3Документ12 страницChapter 3Ngân Lê Thị KimОценок пока нет

- Classroom ActivitiesДокумент5 страницClassroom ActivitiesKaty MarquezОценок пока нет

- Mechanisms of Dimensionality Reduction and Decorrelation in Deep Neural NetworksДокумент9 страницMechanisms of Dimensionality Reduction and Decorrelation in Deep Neural NetworksVaughn JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Bastardized English or Englishized LanguageДокумент30 страницBastardized English or Englishized LanguageMaria Teresa Torrecarion AsistidoОценок пока нет

- LET Review - Part1Документ63 страницыLET Review - Part1NathanJil HelardezОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal and Seminar On Translation - VДокумент3 страницыResearch Proposal and Seminar On Translation - VRi On OhОценок пока нет

- Nur Summer Vacation Task 2023Документ39 страницNur Summer Vacation Task 2023Sobi AfzОценок пока нет

- Speaking CAE 1 PDFДокумент8 страницSpeaking CAE 1 PDFMBОценок пока нет

- Effective Integration of Music in The ClassroomДокумент18 страницEffective Integration of Music in The ClassroomValentina100% (1)

- Trimsatika (Thirty Verses) of VasubandhuДокумент4 страницыTrimsatika (Thirty Verses) of VasubandhuKelly MatthewsОценок пока нет

- Cause and Effect - IntroДокумент19 страницCause and Effect - IntroRanti MulyaniОценок пока нет

- Web ND SocialДокумент9 страницWeb ND SocialxapovОценок пока нет

- Ch.5.Task.2. Partially Complete Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницыCh.5.Task.2. Partially Complete Lesson PlanLuisito GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Cognition and MetACOGNITIONДокумент11 страницCognition and MetACOGNITIONHilierima MiguelОценок пока нет

- Culturally Sustaining PedagogyДокумент2 страницыCulturally Sustaining PedagogyCPaulE33Оценок пока нет

- W12 Language AwarenessДокумент1 страницаW12 Language AwarenessLIYANA OMARОценок пока нет

- 4MS Test 2ND Term Amour Rabah 2024Документ2 страницы4MS Test 2ND Term Amour Rabah 2024alimabouriacheОценок пока нет

- The Forum Symposium As A Teaching TechniqueДокумент6 страницThe Forum Symposium As A Teaching TechniqueV.K. Maheshwari100% (3)

- Technical CommunicationДокумент4 страницыTechnical CommunicationNor Azlan100% (1)

- Physical Education PDFДокумент10 страницPhysical Education PDFdimfaОценок пока нет

- Why Choose Medicine As A CareerДокумент25 страницWhy Choose Medicine As A CareerVinod KumarОценок пока нет

- Fuzzy Jerry M. MendelДокумент2 страницыFuzzy Jerry M. MendelJuan Pablo Rodriguez HerreraОценок пока нет