Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Ballast Water Technology Inpending Challenges

Загружено:

swapneel_kulkarniАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ballast Water Technology Inpending Challenges

Загружено:

swapneel_kulkarniАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

No 2/12 May 2012

Ballast Water Technology 2012 -

Report of the conference, organised by IMarEST and supported by the GloBallast Partnerships Project - Thursday 23 and Friday 24 February 2012 Notes and comments by Dr Alistair Greig, UCL - Rapporteur

The Conference was timely, taking place immediately before MEPC63. The conference was opened by John Wills, IMarESTs technical director who welcomed the many delegates to the conference. By way of introduction he emphasised the enormity of the ballast water challenge and its multidisciplinary nature and that the diversity of different science and technologies involved is considerable. Chris Wiley, Chairman of the IMO Ballast Water Working Group of the IMO put the challenge into perspective in his keynote presentation by stating that from the environmental and financial point of view non-indigenous species pose a bigger threat than oil spills. One of the recurring themes of the Conference was the ability of the industry to meet requirements set out in the IMO Ballast Water Convention, not only from a technical standpoint but also from the more practical consideration of timescale. There were two main areas of concern, both of which are related to the huge scale of the problem, which are installation and regulation. The problem is large both in terms of the number of ships in the Worlds fleet and in terms of the volume of ballast water transhipped globally. The second keynote speaker, Dr David Wright, gave a clear overview of the problem of installation of ballast water treatment plants onto the existing fleet. For new builds, installation is less of a concern. The convention is likely to be ratified by 2013; it has already met the minimum threshold of 30 countries but it is still requires a little over 8% of the worlds gross commercial tonnage for ratification. Once ratified, it will enter into force a year later. However, the timetable in the Convention is fixed and not related to its date of entry into force. Consequently as the Convention has taken longer than expected to be ratified some deadlines have already passed which means these deadlines will have to be met immediately the Convention comes into force. Normally a Convention cannot be amended or changed until it enters into force but the IMO has already granted one delay in some regulations and if ratification is further delayed it might have to amend the timetable again as -1

more key dates are passed. This is introducing a degree of uncertainty within the industry. The deadlines can be viewed in the appendix. Dr Wright said that there are approximately 70,000 vessels required to be fitted with ballast water treatment systems by 2017. This equates to 30-40 systems per day, every day, for the next five years. However, a number of speakers pointed out that owners may find it economically more attractive to retire a ship than absorb the capital and operating costs of a ballast water treatment plant that would only be used for a few years. Additionally, banks may not provide finance for environmental kit on ships because it does not provide a return on investment, instead forcing the ship owners to pay outright. Whilst premature scrapping of ships will ease the ballast water treatment plant installation problem it could have an unforeseen impact on the world fleet. Finally, some ships, such as small chemical tankers and LPG tankers, may simply not have the volume below deck to install a ballast water treatment plant. The marine supply industry is rising to the challenge of producing systems that can treat ballast water and more and more of these are gaining type approval. There are 23 type approved systems and over 60 in some form of development and/or approval. The approval process can take a long time (up to 2 years) and this is also limited by resources. Other challenges include large vessels, high flow vessels and semi-submersibles. Cold water and fresh water are also challenging and not all systems can operate with them. Some systems are not suitable of all ships, for example inert gas, but this does have the advantage of minimal power requirement. Technology is also being exploited to reduce installation times and, equally as important, ship impact. Jurrien Baretta, from Goltens Green Technologies BV demonstrated a 3D laser scanner which can map a compartment in 6 hours with minimal disruption. Even so the whole process from initial negotiation with the owner through delivery of the equipment to installation followed by Class approval can take as little as 9 but up to 18 months. The aim is to streamline the process learning from experience. The duration relies on many factors including availability of equipment, dockyards and workforce with relevant skills; not only for machinery installation but also all the verification and certification processes. As one speaker from a Classification Society said, they do not have a few boxes in their basement full of engineers ready to be unpacked at a moment notice to satisfy the short term surge in demand for installation of ballast water systems, especially as there is still considerable doubt as to the shape and timing of the demand profile. Human resources are important, not only for installation, but also for operation and maintenance. There is a huge education effort required to train the crews of all the ships that are going to be installed with a variety of new ballast water treatment plants. This aspect was addressed by Mr Raul Harris from Videotel Marine International. Other participants commented that the BWC had had insufficient input from seafarers, the people who will have to deal with its consequences on a day-to-day basis. It will be an extra task for them at a key time when efforts are normally concentrated on loading and unloading cargo Eddie Bucknall, Technical Director, Columbia Ship Management proposed an alternative solution to ballast water treatment by increasing the involvement of ports and treating Ballast water as a commodity. He highlighted an issue raised by others, that the IMO had no -2

jurisdiction over ports and that ballast water was seen as a purely a ships problem. His thesis is that for many routes ships travel from regions where freshwater is plentiful and discharge ballast in regions where freshwater is scarce. If fresh water (river water, treated sewage etc.) were used as ballast it could be used in arid countries for irrigation rather than discharged to sea. The extra port infrastructure and pumping costs would be offset by the non-requirement to treat the ballast water, sale of the water and reduced corrosion of the tanks. Ballast-less and Ballast-free ships were only mentioned in passing, as too were the unique problems of FPSOs. An interesting discussion took place on how far a specimen has to be moved before it is considered as non-indigenous. No definitive answer was provided but it was felt to be species and ecosystem dependent. In some cases it could be a few miles for others it could be hundreds of miles. Compliance with the convention and verification of compliance was a major topic with many speakers questioning the practicalities of following the requirements of the Convention to the letter. To do this would require a significant resource to collect representative samples (with what constitutes a representative sample still open to debate) from numerous tanks and then have enough experts, with appropriate laboratory facilities, to test the samples. One issue highlighted by biologists was the difficulty of determining if an organism was viable. This may require more than one expert given the huge variety of life that will be encountered which include; viruses, bacteria, human pathogens, phytoplankton, zooplankton all in different developmental stages (adults, cysts, eggs, resting stages, larvae etc.). The global diversity, and whether the species are from fresh water, coastal waters or open ocean waters also needs to be considered. The required testing could take many hours or even days depending upon the location, the capacity of the laboratory and the degree of compliance expected (will each Port be required to have its own laboratory for example?). However, there is additionally, the conflicting requirement not to impose undue delay on the vessel (article 12). In large ports, such as Singapore, this would require processing samples from several hundred ballast water tanks per day when the typical turnaround time is normally 6 8 hours. At the other extreme are the Small Island Developing States (SIDS); their fragile eco systems are very vulnerable to non-indigenous species and they are very reliant on shipping. 25% of SIDS are economically underdeveloped, even the more developed ones have limited resources, and they would struggle to meet the requirements of the BWMC, yet they are the countries that need it the most. GloBallast is helping less developed countries with dealing with the problems of non-indigenous species and application of the BWMC. One of the problems with the convention is that it was written before there was any experience with sampling or before ballast water treatment technology was developed. Yet the guidance produced is more comprehensive than in any other convention. When written it was a best guess of the worlds experts. Some of the guidance will have to be revisited once the convention comes into force. However, the knowledge that there will be amendments results in a level of uncertainty and all those involved are, as such, slightly less willing to commit to any decision that might be affected as a result of the as yet undefined potential amendments. The ideal solution for sampling is a simple tool, like a breathalyser, that can quickly test a sample at the collection point. This is seen as the ultimate technological goal, but is still some -3

way off. This may make the enforcement task easier and eliminates the tolerance debate. The feeling seems to be that proving gross non-compliance is more realistic than trying to prove full compliance and that Port State Control may be able to rely on this alongside a type approval certificate and proof that the system is being properly maintained and is operating properly. A more pragmatic approach was suggested by a number of speakers who favoured a tiered system of compliance assessment and implementation, with each level increasing in complexity (and duration). Starting with the paper work the ship has filed followed by an on board inspection (of paper work). The next level would be a test sample from one or ballast tanks looking for indicator species or alternatively or in parallel a chemical or particle test could be used to confirm if the ballast water has been treated. More detailed tests could then be conducted as required, culminating in full compliance testing if the results warranted. In the majority of cases only the first level of tests would be required to confirm that proper procedures have been followed with the result that full compliance testing will be a rare event. As time passed ships would establish a history or track record and those with favourable indicators could receive less attention allowing resources to be concentrated on the miscreants. A methodology similar to the above is already being adopted in California where Port state control is confirming that ships are following procedures that are consistent with good ballast water management rather than ensuring that they are meeting the extreme and arguably near impossible, limits imposed by the State. Unfortunately, compliance with procedure does not guarantee effective ballast water treatment. When plants are tested for type approval this is done in one location with water of two distinctly different salinities. These controlled conditions are excellent for benchmarking performance but do not truly mimic the salinity, temperature or variety of species the system will be exposed to during normal operation. There is no requirement for type approval tests to include fresh or cold water as part of the test regime. Nor do the results give a measure of the degradation of the performance of the system with time. The later is important because the layered approach outlined above is vulnerable to a ballast water treatment system that is not working properly. The ship will have followed all procedures in good faith so the paperwork will be in order. Indicators may still show the system has used and a few test samples might not detect the higher survival rate especially if water in tank is stratified and the system failed towards end of cycle. Jon Stewart, International Maritime Technology Consultants Inc. reminded the audience that IMO Conventions are not mandatory and a country may do as it wishes within its own sovereignty. Examples of this already exist and, within the USA, some States have introduced their own regulations, most notably California and New York. He said the US Coast Guard and the US Environmental Protection Agency were working to try and harmonise the regulations within US waters and these appear to be aligning themselves along the lines of BWMC D-2 but that the US might extend the regulations to include vessels as small as 300 Gross Tonnage or over with over 8m3 of ballast capacity. As his N American colleague Chris Wiley pointed out there is a possibility of unilateral implementation if BWMC is not implemented, which could lead to a worst case scenario of a plethora of national and regional rules and regulations. This carries with it the danger of another zebra mussel scale of invasion resulting in a knee jerk reaction of extreme ballast water control measures. One difference is that, where IMO has minimal influence over ports, national -4

administrations have maximal influence. A question that was asked but remained unanswered was; given that the concept of polluter pays is well established, how would this be applied in the case of a new damaging invasion? The conference affirmed that manufacturers are rising to the technical challenges however, uncertainty exists in how and when the Convention will enter into force and how it might be subsequently amended. This in turn is making investment decisions more difficult. The existing timescale is extremely challenging if all ships are to meet the 2017 deadline. A practical, layered approach is identified as a sensible solution to compliance enforcement but there are still a number ethical and legal issues that need be defined and confidence levels established to produce an effective, yet manageable system. One component of this is more synergy between ports and vessels. The BWT2012 Conference was organised by the IMarEST Ballast Water Experts Group. The Ballast Water Expert Group is a Special Interest Group of the IMarEST which focuses specifically on addressing issues concerning ballast water management. The group plans on holding additional conferences in the future details of which, alongside details of the group, can be found at: http://www.imarest.org/Technical/TechnicalActivities/SpecialInterestGroups/BallastWaterEx pertGroupBWEG or by emailing technical@imarest.org

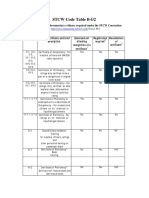

APPENDIX The specific requirements for ballast water management are contained in regulation B-3 Ballast Water Management for Ships: Ships constructed before 2009 with a ballast water capacity of between 1500 and 5000 cubic metres must conduct ballast water management that at least meets the ballast water exchange standards or the ballast water performance standards until 2014, after which time it shall at least meet the ballast water performance standard. Ships constructed before 2009 with a ballast water capacity of less than 1500 or greater than 5000 cubic metres must conduct ballast water management that at least meets the ballast water exchange standards or the ballast water performance standards until 2016, after which time it shall at least meet the ballast water performance standard. Ships constructed in or after 2009 with ballast water capacity of less than 5000 cubic metres must conduct ballast water management that at least meets the ballast water performance standard. Ships constructed in or after 2009 but before 2012, with a ballast water capacity of 5000 cubic metres or more shall conduct ballast water management that at least meets the ballast water performance standard. Ships constructed in or after 2012, with a ballast water capacity of 5000 cubic metres or more shall conduct ballast water management that at least meets the ballast water performance standard.

-5

Вам также может понравиться

- PBCFДокумент4 страницыPBCFswapneel_kulkarni100% (1)

- ClassNK Academy EДокумент14 страницClassNK Academy Eswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Tanker Matters - LP News Supplement PDFДокумент32 страницыTanker Matters - LP News Supplement PDFLondonguyОценок пока нет

- A.E Shop TrialsДокумент1 страницаA.E Shop Trialsswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Increased Safety Stator Winding Temperature Sensors: Specification and Order OptionsДокумент2 страницыIncreased Safety Stator Winding Temperature Sensors: Specification and Order Optionsswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- PistonДокумент7 страницPistonkatarkivosОценок пока нет

- All Kinds of Faults in An Alternator and Their ProtectionДокумент9 страницAll Kinds of Faults in An Alternator and Their Protectionswapneel_kulkarni100% (1)

- Oil Tanker Sizes Range From General Purpose To Ultra-Large Crude Carriers On AFRA Scale - Today in Energy - U.SДокумент3 страницыOil Tanker Sizes Range From General Purpose To Ultra-Large Crude Carriers On AFRA Scale - Today in Energy - U.Sswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Ycnsunom 3. Hull FoulingДокумент22 страницыYcnsunom 3. Hull Foulingswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Antifreeze CoolantsДокумент7 страницAntifreeze Coolantsswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Protection & Coordination - Motor ProtectionДокумент34 страницыProtection & Coordination - Motor ProtectionAdelChОценок пока нет

- Biominoil GuideДокумент49 страницBiominoil Guideswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Understanding Mooring IncideДокумент8 страницUnderstanding Mooring IncideIan MaldonadoОценок пока нет

- JSS 596Документ2 страницыJSS 596swapneel_kulkarni100% (1)

- DNV Gas Carrier Rule PDFДокумент82 страницыDNV Gas Carrier Rule PDFcelebiabОценок пока нет

- Safe Ports, Safe BerthsДокумент22 страницыSafe Ports, Safe Berthsswapneel_kulkarni100% (1)

- DNV Gas Carrier Rule PDFДокумент82 страницыDNV Gas Carrier Rule PDFcelebiabОценок пока нет

- Update On Imo Hook RegulationsДокумент2 страницыUpdate On Imo Hook Regulationsswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Improve Pumps Performance With Composite Wear ComponentsДокумент0 страницImprove Pumps Performance With Composite Wear ComponentsDelfinshОценок пока нет

- Industry Code of Practice On Ship RecyclingДокумент7 страницIndustry Code of Practice On Ship Recyclingswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Economies of Scale in Large Container ShippingДокумент23 страницыEconomies of Scale in Large Container Shippingswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Pump Wear and Wear RingsДокумент3 страницыPump Wear and Wear Ringswsjouri2510Оценок пока нет

- Assessment of Marine Engines Torque LoadДокумент10 страницAssessment of Marine Engines Torque Loadswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Supression of Sloshing in Tank by Reversed U-TubeДокумент11 страницSupression of Sloshing in Tank by Reversed U-Tubeswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- 2010 STCW Manila AmendmentsДокумент6 страниц2010 STCW Manila Amendmentsswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Spectec Amos MaintenanceДокумент2 страницыSpectec Amos Maintenanceswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Ultrasonic Liquid Level IndicatorsДокумент1 страницаUltrasonic Liquid Level Indicatorsswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- Stern Tube SealДокумент16 страницStern Tube SealAdrian IgnatОценок пока нет

- AartiДокумент4 страницыAartiRajalakshmi GajapathyОценок пока нет

- Bourbon Borgstein PDFДокумент2 страницыBourbon Borgstein PDFswapneel_kulkarniОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Junk Rig For BeginnersДокумент10 страницJunk Rig For Beginnersashley_kos8020100% (1)

- KWave ReportДокумент8 страницKWave ReportDenys ShyshkinОценок пока нет

- Charts and Nautical PublicationДокумент48 страницCharts and Nautical PublicationJeet Singh100% (3)

- Starships Stats R& E CensoredДокумент336 страницStarships Stats R& E CensoredClinton GoodОценок пока нет

- Shipmates USS CairoДокумент4 страницыShipmates USS CairoBob AndrepontОценок пока нет

- Mobil Ege 05-B-5 (1993) Marine Loading ArmsДокумент16 страницMobil Ege 05-B-5 (1993) Marine Loading Armskmiloop0% (1)

- Tullow Supply Chain Services ListДокумент17 страницTullow Supply Chain Services ListNyadroh Clement MchammondsОценок пока нет

- Fsru Study OverviewДокумент8 страницFsru Study OverviewMheErdiantoОценок пока нет

- Ship Handling 3Документ25 страницShip Handling 3DheerajKaushal100% (3)

- ATLAS UK SeaClass - Brochure PDFДокумент24 страницыATLAS UK SeaClass - Brochure PDFAndré GoulartОценок пока нет

- Manual Reflecta 1Документ32 страницыManual Reflecta 1Mike Olumide JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Maritime Labour Convention and SEA: Presentation-Viyyash Kumar and NagarjunДокумент20 страницMaritime Labour Convention and SEA: Presentation-Viyyash Kumar and NagarjunViyyashKumarОценок пока нет

- RAK Maritime CityДокумент8 страницRAK Maritime CityAnonymous 95dlTK1McОценок пока нет

- Keeping A Lookout - Colregs Rule 5: Case Study ResponsibilitiesДокумент2 страницыKeeping A Lookout - Colregs Rule 5: Case Study ResponsibilitiesMark GonzalezОценок пока нет

- PSC-Circ-No - 27-2021-Paris-MoU-Tokyo-MoU-CIC-on-Stability-in-GeneralДокумент18 страницPSC-Circ-No - 27-2021-Paris-MoU-Tokyo-MoU-CIC-on-Stability-in-GeneralbagasОценок пока нет

- Functions of A Production PlatformДокумент10 страницFunctions of A Production Platformajwad_hashim5100% (1)

- STCW Code Table B-I/2: List of Certificates or Documentary Evidence Required Under The STCW ConventionДокумент2 страницыSTCW Code Table B-I/2: List of Certificates or Documentary Evidence Required Under The STCW ConventionLita Anggraeni Verawati100% (1)

- DC Endorsement 2015Документ3 страницыDC Endorsement 2015TusharBhagatОценок пока нет

- Adhesive Tape Import Export DataДокумент17 страницAdhesive Tape Import Export DataRohin AhujaОценок пока нет

- BertschiДокумент1 страницаBertschielainejournalistОценок пока нет

- Mooring BuoyДокумент3 страницыMooring BuoyGermán AguirrezabalaОценок пока нет

- Mil Req 1stДокумент278 страницMil Req 1stMary HotCommodity WoodОценок пока нет

- Divya Solanki PDFДокумент15 страницDivya Solanki PDFDeepak PooranachandranОценок пока нет

- 1978 Book UpwellingEcosystemsДокумент310 страниц1978 Book UpwellingEcosystemsÚrsula Martin100% (1)

- Gas Value Chain Explained-1Документ10 страницGas Value Chain Explained-1UJJWALОценок пока нет

- United States Navy Supercarrier - Cvn-68 Uss Nimitz: by JdogДокумент16 страницUnited States Navy Supercarrier - Cvn-68 Uss Nimitz: by Jdogaaronsmith812732Оценок пока нет

- AWE Energia - Company Profile-1Документ6 страницAWE Energia - Company Profile-1helmi_69Оценок пока нет

- MarlawДокумент1 страницаMarlawEko Novianto0% (1)

- ABS - Part 4 Section E - Jan 06Документ755 страницABS - Part 4 Section E - Jan 06HansNieborgОценок пока нет

- OceanofPDF - Com Jewel of The Endless Erg - John BierceДокумент228 страницOceanofPDF - Com Jewel of The Endless Erg - John BierceJoy HussainiОценок пока нет