Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Sharp Les

Загружено:

consulusАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Sharp Les

Загружено:

consulusАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

LIVING IN THE CITY: URBAN ELITES AND THEIR RESIDENCES. MERCHANTS HOUSES IN VICTORIAN LIVERPOOL.

Mr Joseph Sharples University of Liverpool, United Kingdom j.sharples@liverpool.ac.uk

This is an interim report on work being undertaken as part of the Mercantile Liverpool project in the Centre for Port and Maritime History, University of Liverpool. The three-year project began in January 2004. Its aim is to investigate the culture, business practice and built environment of Liverpools merchant community, focusing on the period c.1850-1914. The term merchant is here used principally to describe traders, but is taken to include shipowners, manufacturers and others who derived their wealth from the trading activities of the port. I am responsible for the built environment strand of the project, funded by English Heritage, which will use the evidence of architecture and man-made landscapes to gain a fuller understanding of the way of life, tastes and aspirations of the merchant class. At this stage I am investigating merchants dwellings. Sources used so far include historical maps, street directories, official records of building control (unfortunately very incomplete), architectural drawings, historical photographs and reports in the architectural press. For biographical information about owners and occupiers I have used obituaries, diaries and family papers. The key sources, however, are the buildings themselves and their urban landscape setting. Liverpool was a place of little consequence before the later 17th century. As trade developed from the early 18th century onwards, it grew rapidly into one of the largest and wealthiest towns in England, and for the next two hundred years its leading citizens were not hereditary nobles or landowners, but prosperous merchants. Some merchant families were older than others in 1854 Nathaniel Hawthorne, American consul in Liverpool, sarcastically called them those ancient merchant-princely families, who form the century-old aristocracy of Liverpool but generally speaking, Liverpool money was very new money. 19th-century observers commented on how this sudden acquisition of wealth was reflected in the newness of Liverpool merchants dwellings. Describing Georgian Wavertree Hall in 1831, the author of Lancashire Illustrated considered its sober antiquity exceptional in the neighbourhood of Liverpool, where everything speaks of modern affluence and recent acquirement. Hawthorne was disappointed to find that the interior of Poulton Hall, a house of various periods tenanted by a Liverpool merchant returned from America, had been refurbished so that the impression is of newness, not of age. Sefton Park, a wealthy villa suburb built up in the 1870s and 80s, was mockingly nicknamed Mushroom Park in a local satirical paper, because of its rootless origins and the overnight rapidity of its growth. Such houses, erected in large numbers by the merchant class, or by speculative builders with merchant occupants in mind, provide a direct reflection of the mercantile life-style.

My first aim has been to identify those areas of Liverpool where merchants clustered, using maps of different periods. Some earlier maps (R. Sherriffs of 1823 and Jonathan Bennisons of 1835) are usefully inscribed with the names of owners or occupiers of individual properties. Other large-scale maps clearly reveal those areas where the streets are wider than average and the houses larger, suburbs where villas are arranged with picturesque irregularity in spacious private estates, and outer areas where the grandest mansions are set in the most extensive grounds. Street directories confirm that these areas of greatest amenity were occupied by the merchant class. Having identified these districts, I have selected particular houses for closer scrutiny. I have aimed to choose houses which are well preserved, and for which there is substantial documentation in the form of architectural drawings, contemporary descriptions and historical photographs. I have also focused on owners and occupiers who are well-documented through surviving personal papers, biographies, memoirs and obituaries. A striking fact about merchants is the frequency with which they moved house, street directories making it possible to follow the changing occupancy of a single house over time, and trace the movements of an individual from house to house during the progress of his career. A generally accepted truth about the development of large British commercial and industrial towns in the 19th century is that citizens with sufficient money moved ever further from the congested, insalubrious centre, to more spacious, cleaner, greener locations of the fringes. By studying certain areas in greater depth, however, and by tracing the movements of certain individuals in detail, a more subtly shaded picture of elite residential patterns can emerge, in which factors such as a merchants extended family, and his business and political life, each play a part. The following brief casestudies from the Mercantile Liverpool project show some of the possibilities of this approach. Thomas Worthington Cookson (c.1800-1867) was one of the founders in 1840 of the firm of Hatton & Cookson, shipowners and West African merchants specialising in the palm oil trade, who had business premises in Mersey Street, near the Custom House. Cookson occupied a house in Great George Square, the first of Liverpools large residential squares on the London model, with a central railed garden for the use of residents. Along with nearby Rodney Street and the more extensive Mosslake Fields area, it formed part of the eastward residential expansion of the town in the late 18th-early 19th century, consisting of high-class terraced houses built to a spacious and regular street plan. Great George Square was about 750m from Mersey Street: conveniently close for business, but sufficiently separate for dignity. Around 1854 the Cookson family moved to Seaforth, about 6.5km north of the Exchange that marked the commercial centre of Liverpool. Seaforth, then still part of the towns rural hinterland, had attractive marine views across the Mersey estuary and was home to a number of affluent merchants. Here Cookson and his business partner and brother-inlaw, Edward Hatton, commissioned the local architect William Culshaw to design a pair of identical detached houses, where they lived facing each other across a communal carriage drive. Living close to ones relatives was not uncommon among 19th-century Liverpool merchant families, as we shall see. Cookson died in 1867, leaving personal effects valued at 160,000, Hatton in 1880, leaving somewhat more. They were multi-millionaires in todays terms.

At least two of Cooksons sons lived with their father at Seaforth. The eldest also named T.W. Cookson made the family home his own after their fathers death. Another, Edward Hatton Cookson (1837-1922), stayed with his brother for a few years then moved back into Liverpool in 1874. He established himself in Edge Lane, now a busy main road into the city but then a quiet thoroughfare forming one side of the affluent residential area of Fairfield. Its distance from the Exchange was a little over 3km. Family connections seem to have played a part in this move: street directories of the 1870s list Edward Hatton the uncle after whom E.H. Cookson was named at the Edge Lane house as well as at his Seaforth residence; and another of E.H. Cooksons brothers, Henry Cookson (d.1893), lived just round the corner at 16 Holly Road. Then, in the mid 1880s, Henry Cookson and E.H. Cookson moved from Fairfield to two adjacent houses in the even more select area of Sandfield Park, West Derby, about 6km from the Exchange. This was probably the most exclusive of several private housing estates established on the fringes of Liverpool from the 1840s onwards. Such estates generally had gates and lodges at the entrances, to ensure the residents seclusion and security, and the houses were reached off one or more picturesquely winding drives. At Sandfield Park the houses and the plots they occupied were significantly larger than in other examples, and the occupants were among the cream of Liverpools mercantile elite. Henry Cooksons new house was called Runnymede. It had been built by John Houghton, partner in the firm of Canon, Miller, Houghton & Co, shipowners and merchants. Houghton, the son of a timber merchant resident in Rodney Street, was Liberal in politics and a Baptist by religion, and his later years, spent in retirement, were occupied with charitable and philanthropic work. He died at Runnymede in 1883, leaving over 116,000. Cookson acquired the house, and straight away made significant alterations, plans by the architects F. & G. Holme being approved by the West Derby Urban District Council in September 1884. The works entailed the addition of a billiard room with elaborate plasterwork, and the remodeling of the hall with Renaissance-style paneling. The architects were sufficiently pleased with their work to show the designs in the Liverpool Autumn Exhibition of 1887 at the Walker Art Gallery. The reason for these changes is made clear by Henry Cooksons obituaries, one of which explains that he took an active part in the propagation of the Conservative cause in West Derby, not so much by his platform eloquence as by the munificence of his hospitality When Lord Claud J. Hamilton and the late Hon. W.H. Cross visited the district they were invariably the guests of Mr Cookson at Runnymede; and frequently he extended the welcome of his home to the political workers of West Derby by holding garden parties. A billiard room would probably have been unnecessary to a man of John Houghtons quiet habits and piety, but was essential for political entertaining of the sort practised by Cookson. Henrys brother, E.H. Cookson, made even more substantial alterations to his new home, just 460m away. The house was formerly occupied - and probably built by John Radcliffe, an attorney, listed in the street directories as resident in Sandfield Park from 1864. His house was called Rougemont, and here he died in 1884, leaving just under 21,000. The architectural evidence shows that Rougemont was a considerably smaller house than Runnymede, a square brick villa of two principal storeys, probably with four main rooms on the ground floor. In January and June 1885, E.H. Cookson obtained permission from West Derby Urban District Council to build a porch and make other additions, the effect of which was roughly to double the size of the house,

which he renamed Kiln Hey. He seems to have had the original staircase of Radcliffes house removed, to create a very broad internal corridor. This led to an extension containing an enormous new barrel-vaulted staircase hall and a billiard room, presumably with bedrooms above. E.H. Cookson employed a lesser architect than his brother Henry at Runnymede, and aesthetically the results were rather pedestrian, but the transformation was extraordinary in its scale. Its main provisions were areas for masculine recreation and relaxation, and generously proportioned circulation routes. The new porch was no mere vestibule, but an exceptionally large, marble-paved room with a coved ceiling, spacious enough for the dignified reception of large groups of guests. As with his brother Henry, E.H. Cooksons move to Sandfield Park and upgrading of his new house coincided exactly with developments in his political life. He was elected a Conservative councillor for West Derby in April 1884, and was returned unopposed on three subsequent occasions. The acquisition and extension of Kiln Hey was almost certainly motivated by the need to entertain political colleagues and business associates, and was clearly not the result of domestic requirements, since Cookson lived and died a bachelor. The high point of his political career came when he served as Lord Mayor of Liverpool in 1888-9, having been named Mayor-elect in October 1888. The previous month, Kiln Hey was photographed by the specialist London-based architectural photographer Bedford Lemere. According to the photographers day-book, the pictures were commissioned by the Liverpool interior decorators Turner, Son & Walker, which strongly suggests that they record a recently completed decorative scheme by the firm. It appears that having enlarged his new house three years earlier when he entered politics, Cookson then redecorated it in anticipation of his mayoral year. The photographs show elaborate panelling in the dining room and library, in a historicizing style which might be called Old English, while the drawing room is in the Adam taste, with neoclassical ceiling and fireplace, and wall paintings inspired by Pompeian murals. The overall aim was perhaps to evoke the stylistic mix of an English country house with rooms of different historical periods, and to give the second-generation merchant Cookson the architectural trappings usually associated with an aristocratic pedigree. In one particular respect the decoration seems explicitly to attempt this: as at Henry Cooksons Runnymede, the staircase window at Kiln Hey has heraldic stained glass in which the central feature is the Cookson coat of arms. E.H. Cooksons house may be seen as reflecting the self-image of one of Liverpools successful Victorian merchants, and other photographs of Liverpool houses by Bedford Lemere show similar characteristics. Without contextual evidence, however, who is to say if these interiors illustrate the aspirations of the occupier, or merely those of the professional decorator? One unusually well-documented case shows the danger of drawing conclusions from architectural evidence alone. A.G. Kurtz was an alkali manufacturer who lived at Wavertree, on the outer fringes of Liverpool, and had his factory 13km away at St Helens. His home was Grove House, later known as Dovedale Towers, a building dating from the 1830s or earlier, which he enlarged in 1870-1; it survives in rather mangled form as a pub. Looking at it today, an observer who knew nothing about Kurtz might see his house as an expression of the ostentation and vulgarity of a man with more money than taste, a caricature of the Victorian selfmade man of business. Kurtz, however, was a distinguished art collector, amateur musician and man of culture. He kept voluminous diaries in which his business life

plays a secondary part, while his reading, music-making, and attendance at the theatre and concert hall are minutely recorded and analysed. The diaries make clear that he strongly disliked the alterations to his house, which had been designed for him by a friend, Charles Z. Herrmann. Surveying the new entrance front, he wrote: the tower looks to me quite out of proportion & the marble columns outside the upper story appear unnecessary and pretentious. Indeed, that is the appearance of the whole place now, & I feel rather sorry that I have had it altered. Of course, its useless regretting this now, but everything C.Z.H. takes in hand has a look of being overdone. The marblework in the hall would be in keeping in a noblemans house, but with my simple tastes & with the little company I keep, it seems out of character. This paper is a report on work in progress, and general conclusions must wait until a later stage of the project. Nevertheless - and bearing in mind the example of Kurtz as a caveat - work so far carried out suggests that houses will prove a valuable source of qualitative information about Liverpools mercantile elite. Interpreted in the light of biographical information about their occupants, they can provide a vivid, tangible record, not just of domestic life and ties of kinship, but also of a merchants progress in business and the public sphere; and they embody personal wealth in a way that fleshes out the bald figures of the Calendar of Probate.

Вам также может понравиться

- Letteratura Inglese 2Документ36 страницLetteratura Inglese 2Marta MulazzaniОценок пока нет

- LIVERPOOL - HISTORY AND CULTURE OF A MAJOR BRITISH PORT CITYДокумент10 страницLIVERPOOL - HISTORY AND CULTURE OF A MAJOR BRITISH PORT CITYBobby Mihai BogdanОценок пока нет

- Liverpool (History, Culture, Character & Sport)Документ36 страницLiverpool (History, Culture, Character & Sport)Luka RisticОценок пока нет

- 0322StNicholas District-Strivers RowДокумент6 страниц0322StNicholas District-Strivers RowsandritaОценок пока нет

- Great Estates of LondonДокумент56 страницGreat Estates of LondonantonyОценок пока нет

- History ProjectДокумент8 страницHistory Projecttaeminyun18Оценок пока нет

- The English Medieval Town A Reader in English Urban History 1200 1540 9781315846088 9780582051287 0582051290 0582051282 - CompressДокумент300 страницThe English Medieval Town A Reader in English Urban History 1200 1540 9781315846088 9780582051287 0582051290 0582051282 - CompressЮра Шейх-ЗадеОценок пока нет

- Milne, Erber, UH 2021Документ26 страницMilne, Erber, UH 2021volpedoОценок пока нет

- Hiller2019 Chapter Period2LondonInTheEnlightenmenДокумент50 страницHiller2019 Chapter Period2LondonInTheEnlightenmenFermilyn AdaisОценок пока нет

- Chilham, Kent's beautifully preserved 15th century housesДокумент6 страницChilham, Kent's beautifully preserved 15th century housesHar IshОценок пока нет

- The Wharncliffe Companion to Ipswich: An A to Z of Local HistoryОт EverandThe Wharncliffe Companion to Ipswich: An A to Z of Local HistoryОценок пока нет

- Elizabethan London IntroductionДокумент40 страницElizabethan London IntroductionFermilyn AdaisОценок пока нет

- Haverhill, Massachusetts: From Town to CityОт EverandHaverhill, Massachusetts: From Town to CityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Outras Fontes Bibliográficas - LondresДокумент15 страницOutras Fontes Bibliográficas - LondresCatarina SilvaОценок пока нет

- PG 21218Документ86 страницPG 21218qqqq2222qqqqОценок пока нет

- Kew (/kju /) Is A District in The LondonДокумент109 страницKew (/kju /) Is A District in The LondonArcely GundranОценок пока нет

- New York City's History and Cultural LandmarksДокумент46 страницNew York City's History and Cultural LandmarksChris IonitaОценок пока нет

- The Lost Back-to-Back Streets of Leeds: Woodhouse in the 1960s and '70sОт EverandThe Lost Back-to-Back Streets of Leeds: Woodhouse in the 1960s and '70sОценок пока нет

- Machrihanish Bay - Charles Gilbert Heathcote (1841 - 1913)Документ9 страницMachrihanish Bay - Charles Gilbert Heathcote (1841 - 1913)Kintyre On RecordОценок пока нет

- Look Up, Albuquerque! A Walking Tour of Albuquerque, New MexicoОт EverandLook Up, Albuquerque! A Walking Tour of Albuquerque, New MexicoОценок пока нет

- Parnell House Information Sheet 2024Документ2 страницыParnell House Information Sheet 2024Julia da Costa AguiarОценок пока нет

- Hainis OYTOPIA 59Документ3 страницыHainis OYTOPIA 59consulusОценок пока нет

- Bio O°Ia Kai Koinønikh Bapbapothta 13Документ4 страницыBio O°Ia Kai Koinønikh Bapbapothta 13consulusОценок пока нет

- Grollios OYTOPIA 43Документ8 страницGrollios OYTOPIA 43consulusОценок пока нет

- H Â Èûùôï Ùô Èôèîëù Ùô IkaДокумент4 страницыH Â Èûùôï Ùô Èôèîëù Ùô IkaconsulusОценок пока нет

- Epistoles OYTOPIA 44Документ1 страницаEpistoles OYTOPIA 44consulusОценок пока нет

- Grigoropoylos OYTOPIA 43Документ5 страницGrigoropoylos OYTOPIA 43consulusОценок пока нет

- Georgioy OYTOPIA 50Документ11 страницGeorgioy OYTOPIA 50consulusОценок пока нет

- Bitsakis OYTOPIA 50Документ4 страницыBitsakis OYTOPIA 50consulusОценок пока нет

- 329 KelesidouДокумент0 страниц329 KelesidouconsulusОценок пока нет

- Basi OukaДокумент98 страницBasi OukaconsulusОценок пока нет

- Book ReviewДокумент4 страницыBook ReviewconsulusОценок пока нет

- 415 TsakiriДокумент183 страницы415 TsakiriconsulusОценок пока нет

- Athanasakis OYTOPIA 48Документ21 страницаAthanasakis OYTOPIA 48consulusОценок пока нет

- Bickerton OYTOPIA 70Документ14 страницBickerton OYTOPIA 70consulusОценок пока нет

- Argeitis Oytopia 37Документ3 страницыArgeitis Oytopia 37consulusОценок пока нет

- Won Ne BergerДокумент6 страницWon Ne BergerconsulusОценок пока нет

- Andrade OYTOPIA 54 PDFДокумент5 страницAndrade OYTOPIA 54 PDFconsulusОценок пока нет

- 321 RabavilaДокумент212 страниц321 RabavilaconsulusОценок пока нет

- Wartofsky Oytopia 10Документ18 страницWartofsky Oytopia 10consulusОценок пока нет

- Terzibasoglu PDFДокумент6 страницTerzibasoglu PDFconsulusОценок пока нет

- Sideri Theoharis PDFДокумент9 страницSideri Theoharis PDFconsulusОценок пока нет

- Uncommon Threads The Role of Oral and Archival Testimony in The Shaping of Urban Public Art. Ruth Wallach, University of Southern CaliforniaДокумент5 страницUncommon Threads The Role of Oral and Archival Testimony in The Shaping of Urban Public Art. Ruth Wallach, University of Southern CaliforniaconsulusОценок пока нет

- Wellmer Leviathan 3Документ31 страницаWellmer Leviathan 3consulusОценок пока нет

- Zhongqiao OYTOPIA 54Документ14 страницZhongqiao OYTOPIA 54consulusОценок пока нет

- Won Ne BergerДокумент6 страницWon Ne BergerconsulusОценок пока нет

- Whitebook Leviathan 4Документ21 страницаWhitebook Leviathan 4consulusОценок пока нет

- Weeks Outopia 28Документ17 страницWeeks Outopia 28consulusОценок пока нет

- Pelkonen KohlДокумент6 страницPelkonen KohlconsulusОценок пока нет

- Wartofsky Oytopia 10Документ18 страницWartofsky Oytopia 10consulusОценок пока нет

- Pelkonen KohlДокумент6 страницPelkonen KohlconsulusОценок пока нет

- The Baroda Pamphlet Issue No1Документ12 страницThe Baroda Pamphlet Issue No1V DivakarОценок пока нет

- The City and The Moving Image Urban Projections (PDFDrive)Документ298 страницThe City and The Moving Image Urban Projections (PDFDrive)pabloОценок пока нет

- A History of Feudal Mills and the Late Richard BennettДокумент256 страницA History of Feudal Mills and the Late Richard BennettoceanpinkОценок пока нет

- University of Liverpool Literature ReviewДокумент8 страницUniversity of Liverpool Literature Reviewafmzwlpopdufat100% (1)

- Exploring The Role of Stakeholders in Place Branding - A Case Analysis of The 'City of Liverpool'Документ19 страницExploring The Role of Stakeholders in Place Branding - A Case Analysis of The 'City of Liverpool'Hasnain AbbasОценок пока нет

- EM2301. Practical Class 6Документ11 страницEM2301. Practical Class 6huy phanОценок пока нет

- Matthew King Sound Engineer CVДокумент1 страницаMatthew King Sound Engineer CVa8504447Оценок пока нет

- Cities of Great BritainДокумент1 страницаCities of Great BritainПедоренко Дар'яОценок пока нет

- Aaron Carroll's Curriculum VitaeДокумент3 страницыAaron Carroll's Curriculum VitaeAaron CarrollОценок пока нет

- The Great MetropolisДокумент146 страницThe Great MetropolisLyric Robertson100% (1)

- Webquest On LiverpoolДокумент2 страницыWebquest On Liverpooldelage100% (1)

- A Lasting Legacy: Mab Lane Community WoodlandДокумент7 страницA Lasting Legacy: Mab Lane Community WoodlandJulian DobsonОценок пока нет

- Future EuropeДокумент2 страницыFuture EuropeLore BallesterosОценок пока нет

- Liverpool is in the north-west of England. Where’s Toby's mum from?2Документ14 страницLiverpool is in the north-west of England. Where’s Toby's mum from?2Ruku Goval100% (1)

- The Art of Social Prescribing - Kerry WilsonДокумент14 страницThe Art of Social Prescribing - Kerry WilsonNCVOОценок пока нет

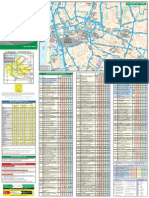

- Chester Bus Exchange - Chester Rail Station - Cheshire Oaks - Ellesmere Port - Bromborough - LiverpoolДокумент11 страницChester Bus Exchange - Chester Rail Station - Cheshire Oaks - Ellesmere Port - Bromborough - LiverpoolTom BruceОценок пока нет

- Tate Annual Report 1819 8mbДокумент141 страницаTate Annual Report 1819 8mbLanxi JiangОценок пока нет

- Britain in BriefДокумент34 страницыBritain in BriefVincent NavarroОценок пока нет

- Event Guide-Catalog Exhibition, Independents Liverpool Biennial 2014Документ28 страницEvent Guide-Catalog Exhibition, Independents Liverpool Biennial 2014B. Ely-MeditОценок пока нет

- The Perfect 1 Day Liverpool Itinerary: Top Beatles Sites & Waterfront MuseumsДокумент1 страницаThe Perfect 1 Day Liverpool Itinerary: Top Beatles Sites & Waterfront MuseumsDaniel Caballero VillarpandoОценок пока нет

- CP Graduates LiverpoolДокумент16 страницCP Graduates Liverpoolnelly1996Оценок пока нет

- The Guide to Blood BrothersДокумент36 страницThe Guide to Blood Brothersbb domanОценок пока нет

- Watson JonathanДокумент320 страницWatson Jonathanjessie666Оценок пока нет

- Liverpool One BookДокумент75 страницLiverpool One Bookdstr311560Оценок пока нет

- The Social Life of Port Architecture: History, Politics, Commerce and CultureДокумент20 страницThe Social Life of Port Architecture: History, Politics, Commerce and CultureAll Little NeedsОценок пока нет

- Winter Visitor Guide (Low Res)Документ21 страницаWinter Visitor Guide (Low Res)Budi PrastyoОценок пока нет

- Cohen 1995Документ14 страницCohen 1995Erkam CömertОценок пока нет

- "Too Ghastly To Believe?" Liverpool, The Press and The May Blitz by Guy Hodgson, Liverpool John Moores UniversityДокумент5 страниц"Too Ghastly To Believe?" Liverpool, The Press and The May Blitz by Guy Hodgson, Liverpool John Moores UniversityTHEAJEUK100% (1)

- Sara Cohen, Sounding Out The Place, Production of Locality (1995)Документ14 страницSara Cohen, Sounding Out The Place, Production of Locality (1995)Dinadie100% (1)

- Liverpool Area: Public Transport Map and GuideДокумент2 страницыLiverpool Area: Public Transport Map and GuideAlícia Fwn100% (1)