Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Wto

Загружено:

Thilaga SenthilmuruganИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Wto

Загружено:

Thilaga SenthilmuruganАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The World Trade Organization (WTO) deals with the global rules of trade between nations.

Its main function is to ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible.

The WTO is a rules-based, member-driven organization all decisions are made by the member governments, and the rules are the outcome of negotiations among members.

Critical appraisals of the current and potential benefits from developing country engagement in the WTO focus mainly on the Doha Round of negotiations. This paper examines a different aspect of developing country participation in the WTO: use of the WTO dispute settlement system to enforce foreign market access rights already negotiated in earlier rounds of multilateral negotiations. We examine data on developing country use from 1995 through 2008 of the WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) to enforce foreign market access. The data reveal three notable trends: developing countries sustained rate of self-enforcement actions despite declining use of the DSU by developed countries, developing countries increased use of the DSU to self-enforce their access to the markets of developing as well as developed country markets, and the prevalence of disputes targeting highly observable causes of lost foreign market access, such as antidumping, countervailing duties, and safeguards. The paper also examines how introduction of the Advisory Centre on WTO Law (ACWL) into the WTO system in 2001 has affected developing countries use of the DSU to self enforce their foreign market access rights. A first pass at the data indicates that developing country use of the ACWL mirrors their use of the DSU more broadly; the ACWL has had little effect in terms of introducing new countries to DSU self-enforcement. A closer look at the data reveals evidence on at least three channels through which the ACWL may be enhancing developing countries ability to self-enforce foreign market access: increased initiation of sole-complainant cases, more extensive pursuit of the DSU legal process for any given case, and initiation of disputes over smaller values of lost trade.

WTO CONCERNED OVER HUMAN RIGHTS APPRAISAL REPORT The head of the WTO, in a letter to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, has expressed the trade bodys deep concern with the language, methodology and main conclusions of a recent report on globalisation and its impact on human rights by two Special Rapporteurs. by Chakravarthi Raghavan

Geneva, 27 August 2000 -- The head of the World Trade Organization (WTO), in a letter to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, has expressed the trade bodys deep concern with the language, methodology and main conclusions of the recent report to the SubCommission on Human Rights by two Special Rapporteurs. The preliminary report, Globalization and its Impact on Full Enjoyment of Human Rights was by two jurist members of the Sub-Commission, and had made a critical appraisal of the WTO and the Bretton Woods Institutions, in assessing their framework, the policies they promote and their decision-making. The report had called for a critical reconceptualization of policies and instruments of international trade, investment and finance. In relation to the WTO, the report had been critical of its rules and processes, and had faulted several parts of the WTO agreements, including its dispute settlement procedures, the TRIPS agreement and the patenting issues, particularly of life forms and plant varieties. The two experts, Mr.Joseph Oloka-Onyango from Nigeria and Ms. Deepika Udagama of Sri Lanka, in focusing on the roles of the WTO and the Bretton Woods Institutions, had underscored that the globalization phenomenon had promoted policies which benefited fewer and fewer people. The WTO, the Special Rapporteurs said, was superficially a democratic institution functioning on the basis of one-member-one-vote and consensus decision-making - but that such superficial equality nevertheless masks a serious inequality in both the appearance and reality of power in the institution... in the deliberations and negotiations over further goals of

trade liberalization, the WTO has demonstrated particular opacity in the face of the demand for transparency. While trade and commerce was the principal focus of the WTO, the organization has extended its purview to encompass additional areas beyond what could be described as within its mandate, the rapporteurs said. Even its purely trade and commerce activities have serious human rights implications, compounded by the fact of scant (indeed only oblique) references to the principles of human rights. The net result, the two experts said, is that for certain sectors of humanity, particularly the developing countries, the WTO is a veritable nightmare. Conveying the WTO heads concerns over the report to Mary Robinson, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the WTO Deputy Director-General Miguel Rodriguezs letter argues that the WTO rules were negotiated and agreed by consensus by all WTO members, including developing countries who make up two-thirds of the membership, and that it would be difficult to understand why the 130 current WTO members, and the 30 developing countries and transition economies actively in the process of acceding would be willing to abide by unfair rules. The Rodriguez letter also claims that the failure to launch a new round of negotiations actually demonstrated that in fact the WTO functioned on consensus, and any member could block decisions, and that the central WTO principles of decision-making by consensus and most-favoured-nation treatment and non-discrimination help to reduce inequalities of bargaining power at the WTO. The letter argues that apart from the reference to patents, the report of the Special Rapporteurs has not identified any cases of alleged conflict between the WTO and the human rights conventions. It also argues that the intellectual property rights (in the WTO/TRIPS) is a right flowing out of the UN Universal Declaration on Human Rights. The WTO letter further complains that sweeping conclusions have been drawn on the WTO and its agreements virtually unsubstantiated by any empirical evidence. The two Special Rapporteurs (who have been mandated by the Sub-Commission to finalise their report) have been, however, invited to meet informally with WTO senior officials, and

have the opportunity to understand the procedural and substantive content of the WTO and its functioning. The WTO letter, and its final para requesting Mary Robinson to convey the WTO views to those responsible for the preparation and oversight of the report, suggests that the secretariat is not aware of the processes of the UN Human Rights bodies and the role of Special Rapporteurs who are commissioned to prepare and present such reports.-SUNS4728 The above article first appeared in the South-North Development Monitor (SUNS) of which Chakravarthi Raghavan is the Chief Editor. 2000, SUNS - All rights reserved. May not be reproduced, reprinted or posted to any system or service without specific permission from SUNS. This limitation includes incorporation into a database, distribution via Usenet News, bulletin board systems, mailing lists, print media or broadcast. For information about reproduction or multi-user subscriptions please e-mail <suns@igc.org >

A Critical evaluation of WTO trade sanctions

WTO TRADE SANCTIONS: A CRITICAL APPRAISAL

The WTO trade sanctions will be evaluated in terms of their consistency with the law of State responsibility and their advantages and disadvantages. A. Are Trade sanctions consistent with the general international law of State responsibility? Since the WTO is a rule-based international organization composed primarily of sovereign states, the law of the WTO is nothing but international law (albeit a special type of international law) and its sources are basically the sources of international law as enunciated in Article 38 (1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice. The Agreement Establishing the WTO is a particular international convention within the meaning of Article 38(1) (a), as are the covered agreements. Customary international law plays a specific role in WTO dispute settlement by virtue of Article 3.2 of the DSU, which provides that the purpose of dispute settlement is to clarify the provisions of the WTO Agreements in accordance with customary rules of interpretation of public international law.

Therefore, one way of appraising the WTO trade sanctions is to examine whether it is consistent with public international law in general and the law of State responsibility in particular. The seminal work of the International Law Commission Articles on Responsibility of States for internationally Wrongful Acts - was adopted by the General Assembly on 28 January 2002. It addresses the notion of countermeasures, based on relevant state practice, judicial decisions and doctrinal writings, the recognized sources

of international law. According to general international law, countermeasures are justified under certain circumstances. Article 49 (1) of the Articles on States Responsibility provides that an injured State may only take a countermeasure against a State which is responsible for an internationally wrongful act in order to induce that State to comply with its obligations. The permissible objective of countermeasures, therefore, is to induce the wrongdoer state to comply with its obligations. The WTO trade sanctions can be said to be consistent with this rule because in EC-Bananas III, the Arbitrators confirmed that the purpose of countermeasures (trade sanctions) was to induce compliance. Nonetheless, according to the law of state responsibility, the wrongdoer state has two obligations to comply with: (1) to cease the wrongful conduct if it is continuing and (2) to provide reparation to the injured state. As a WTO trade sanction aims to make a non-complying measure to be compliant, the first obligation under the general international law can be said as satisfied. Even in respect of the obligation to cease the wrongful act, an obvious weakness of the trade sanctions (countermeasures) under DSU is that achieving compliance may be more possible if the complaining state is the developed members of the WTO. For a weaker member (for example, a developing state), faced with non-compliance by a

disproportionately stronger member, the imposition of countermeasures may make compliance very hard to achieve. Under general international law, the responsible state is again under an obligation to make full reparation for the injury caused by the wrongful act. As laid down in the Factory of Chorzow case, Reparation must, as far as possible, wipe out all the consequences of the illegal act and re-establish the situation which would, in all probability, have existed if that act had not been committed.Restitution in kind, or, if this is not possible, payment of a sum corresponding to the value which a restitution in kind would bear. According to the Articles on state responsibility, full reparation can take the form of restitution, compensation and

satisfaction, either singly or in combination. However, there is nothing in the DSU to satisfy the most important obligation of the wrongdoer state under general international law, namely, to provide reparation to the injured state. With few exceptions, WTO rulings have not required the member in breach of WTO rules to make reparation for the damage caused in the past. Until now, WTO remedies have offered only prospective relief, that is, the withdrawal of the inconsistent measure. It is common knowledge that principle of proportionality applies to counter measures. Article 51 of the Articles on State Responsibility summarises the requirement of proportionality in these words: Countermeasures must be commensurate with the injury suffered, taking into account the gravity of the internationally wrongful act and the rights in question. Proportionality is a well-established requirement for taking countermeasures and widely recognized in state practice, doctrine and jurisprudence. In Naulilaa case, it was held that one should certainly consider as excessive and therefore unlawful reprisals out of all proportion to the act motivating them. In the Air Services arbitration between the United States and France, the Tribunal ruled that: It is generally agreed that all countermeasures must, in the first instance, have some degree of equivalence with the alleged breach: this is a well-known rule. It has been observed, generally, that judging the proportionality of countermeasures is not an easy task and can at best be accomplished by approximation. In the above case, the countermeasures taken by the United States (to suspend Air France flights to Los Angeles) were in the same field as the initial measures (Frances refusal to allow change of gauge in London on flights from the United States) and concerned the same routes, although they were rather more severe as far as their economic effect on the French carriers than the initial French action. The International Court of Justice has had an opportunity to rule on the requirement of proportionality in Gabcikovo - nagymaros Project case. In that case, the Court held that the effects of a countermeasure must be commensurate with the injury suffered, taking account of the rights in question. The Court therefore took into consideration the quality or character of the rights in question as a matter of principle and (similar to the Tribunal in the Air Services case) did not assess the question of proportionality only in quantitative terms. It is therefore the established rule of general international law that proportionality must be assessed taking into consideration not only the purely quantitative element of the injury

suffered, but also qualitative factors such as the importance of the interest protected by the rule infringed and the seriousness of the breach. Do the WTO trade sanctions comply with the proportionality requirement of general international law? The DSU requires that the level of the suspension of concessions or other obligations shall be equivalent to the level of the nullification or impairment. Although the WTO trade sanctions will not generally be out of proportion, the lack of a retrospective remedy may prevent WTO countermeasures from being commensurate with the injury suffered. Then what is the rationale behind the WTO legal system not to allow full reparation as required under general international law? Why is it that it only focuses on the trade sanctions to be commensurate with the level of nullification or impairment? The WTO regime has to be understood and interpreted in light of the original GATT framework, that is, as a balance of negotiated concessions, not primarily as a set of legal rules. A state does not become a WTO member simply by virtue of having ratified WTO agreements. In addition to the multilateral obligations set out in the WTO agreements, the new member has to agree to a series of trade concessions, tariff reductions, market access commitments and so on. A member-member relationship is founded on a delicately negotiated balance not only of rights and obligations explicitly enshrined in WTO agreements, but also of trade concessions. The outcome is that instead of tackling breaches of international law obligations, the WTOs dispute settlement system focuses on the nullification or impairment of benefits. That is the main reason why the WTOs remedy of last resort is to suspend concessions or other obligations up to the level of the nullification or impairment. AWTO member state may be taken action when and because it upsets the balance negotiated with another member, not because it violates multilaterally agreed rules on place for the benefit of all WTO members. That is why some writers are criticizing on this influence of GATT over WTO as a package of bilateral equilibria and arguing for the acknowledgment of WTO rules as international legal obligations and for a more collective enforcement mechanism in the WTO rather than unilateral trade sanctions. Article 50 (1) of the Article on State Responsibility provides, inter alia, that counter measures shall not effect obligations for the protection of fundamental human rights and obligations under peremptory norms of general international law. The WTO trade sanctions could be in tension with this rule if we considered economic rights of the private actors in member States as fundamental human rights. In its General Comment 8 (1997), the Committee on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights discussed the effect of economic sanctions on civil populations and especially on children and stressed that . It is essential to distinguish between the basic objective of applying pressure upon the governing elite of a country to persuade them to conform to international law, and the collateral infliction of suffering upon the most vulnerable groups within the targeted country. Under Article 53, countermeasures shall be terminated as soon as the responsible state has complied with its obligations. The DSU has no provision designed to achieve a rapid termination should the winning party resists lifting its sanctions. This defect may need an amendment to the DSU. The general idea is that the mechanism of trade sanctions under the DSU has to be fair ly inconformity with the international law of state responsibility. It is, however, to be noted that insofar as there are explicit provisions in the DSU which clearly depart from general international law, they are to be regarded as special law (lex specialis) and by virtue of Article 55 of the Articles on State Responsibility, general international law does not apply to these situations. B. Advantages of trade sanctions The very first argument for having trade sanctions is that they provide WTO with teeth. Them ost striking defect of international organizations of universal character is lack of effective enforcement machinery. Take the United Nations as an example. Despite being the most important organization of the present day, its enforcement machinery depends entirely on the unanimity of the Big Five, which has made the Organization paralyzed in a number of major crises. Therefore, the advocates of trade sanctions argue that the WTO can be seen as the only international organization (apart from some regional organizations) with teeth, namely, trade sanctions against members, which violate its rules. The second argument is that the WTO is a rule- based system and trade sanctions may induce compliance with rules. A good example is Brazil-Aircraft case where Brazil complied with the WTO agreements after the authorization of trade sanctions. The deterrent effect of trade sanctions can also be taken into consideration, that is, whether the threat of sanctions contributes to compliance in order that it is not necessary to impose sanctions. In a few WTO cases, the threat of sanctions seems to have effect on non-complying governments. For instance, in Australia--Measures Affecting Importation of Salmon (Australia-Salmon), the

WTO compliance panel held that Australia had not corrected the violation found earlier. Australia came into compliance only when Canada sought authorization to impose Canadian $ 45 million in trade sanctions. Nevertheless, reservations must be made to the above argument that trade sanctions in ducecompliance. An analysis of some of the high profile disputes (for example, banana and beef hormones cases) demonstrates the WTOs apparent inability to achieve compliance especially from superpower nations. The banana dispute in particular indicates the difficulties caused by disagreements among parties as to what constitutes full compliance. The implementation process itself provides opportunities for the losing party to delay compliance through the use of political strategies within the WTO. The disputes over bananas and beef hormones show that the EU, and possibly others, may prefer to see the imposition of sanctions rather than comply with the WTO ruling. This disturbing trend will seriously undermine the effectiveness of the WTO dispute settlement process. Although the EU has stopped short of outright rejection of the negative decisions, it has interpreted decisions in a way than falls short of full compliance and has caused lengthy delays. Indeed, without the ability to block an adverse ruling, long delays and non-compliance may actually become more viable alternatives. The bananas and beef hormones disputes reveal that the WTO is ineffective at preventing both delay and non-compliance. B. Disadvantages of trade sanctions Trade sanctions may damage the economy of the imposing country (self punishing). It is common knowledge that while sanctions may contribute to inducing compliance by the violating country, they at the same time hurt citizens of the imposing country and its own economy. It means that the teeth bite the country imposing the sanctions. In Bananas and Hormones, for example, the U.S. government imposed high tariffs on imports from the EC. This action backfired and adversely affected domestic users in the United States, who suffered a loss of choice and probably had to pay higher prices for substitute products. In the Bananas dispute, the WTO arbitrators admitted that a suspension of concessions may also entail, at least to some extent, adverse effects for the complaining party seeking suspension. Trade sanctions may contradict the raison detre of the WTO. The ultimate aim of the WTO is free trade through gradual liberalization of trade and the main purpose of dispute settlement mechanism is to maintain the balance of trade concessions. Trade sanctions, which are in effect the authorization to exercise trade restrictions, contravene the very spirit of the

WTO. As Charnovitz has rightly put: International organizations do not generally contradict their own raison detre in the name of sanctions. The World Health Organization does not authorize one party to spread viruses to another. The World Intellectual Property Organization does not fight piracy with piracy. So the WTOs use of trade restrictions to promote free trade is bizarre. Trade sanctions favor larger economies over smaller ones. Sanctions are much less effective for developing countries than for developed ones because the former lack the economic or political might to employ them in responding to the non-compliance by the latter. The appraisal in the previous section of the six disputes in which trade sanctions were authorized clearly indicated that those which have taken the advantage of trade sanctions are developed countries like US, EU, Japan, Canada, and Australia. That is why there are proposals to tackle this problem by allowing sanctions to be imposed collectively. These should be considered seriously in the negotiations to improve dispute settlement mechanism. Besides the size of the economy, other determinants for a successful trade sanction is the import dependency of the state taking sanction and the export dependency of the target state. A highly import dependent country may find it hard to use sanctions. A highly export dependent country (like Australia) may find itself vulnerable to the threat of sanctions. In cases of non-compliance, it is often found that the political cost of compliance is too high. Although it is true that each government is obliged to comply with WTO rules, it is not sure whether lawmakers will agree to get rid of a non-complying measure. In some cases, the legislative body adamantly opposes to amending legislation, which is WTO nonconsistent. In many cases, local people and companies are against any government measure which would take away subsidies or special favours for them. Due to self-defeating nature of trade sanctions, we may fairly conclude that disadvantages outweigh advantages. As rightly pointed out by some analysts, trade sanctions are bad policy and they undermine the entire WTO system, which is based on mutually agreed trade liberalization.

As an overall assessment, although fundamental positions have not changed, in the present authors view it seems exist a genuine and sincere desire on the part of delegations to move forward and resolve the remaining differences in these negotiations, so as to be ready to contribute to any movements in the wider context of the Doha Round negotiations. Then, we will try to expose a reflection of the state-of-play and of remaining challenges, in particular in the two key areas of legal effects and participation. With respect to the question regarding the consequences that should flow from an entry on the international register, two general approaches are on the table, namely that (a) an entry should result in better information being available to and used by decision makers and national systems, and (b) that an entry should result in a legal presumption in national systems. According to minimalist approach group, a legal presumption is not acceptable for a number of reasons: firstly, a legal presumption would increase the legal protection for GIs, and this would be outside the scope of this negotiation, which is only about facilitating protection; secondly, a legal presumption would violate the principle of territoriality; and, thirdly, a legal presumption would alter the balance of rights and obligations in the TRIPS Agreement. By contrast, these countries prefer a limited information system in which national

GIs would be notified and incorporated automatically. However, WTO Members sponsoring this system have not yet explained how they would implement the obligation to consult and take into account the information on the register. As legal uncertainties for market operators, whether they were GI or non-GI operators, have to be avoided, there is need for further explanations on this issue. The Joint Proposal calls for the establishment of a simple database as a source of information that Members authorities might or might not consult, and, even if they consult, it is unclear which consequences they would attach to it. In this authors view, it should not be up to WTO Members to decide whether or not to take into account information on the register, essentially for the following reasons: firstly, leaving countries to decide would create legal uncertainty and discrepancies, and would of course not be in the interest of the right holders or of business in general; and secondly, it did not fulfil the mandate which called for a registration system, not a database system, which would amount in practice to a duplication of the information already provided by the applicants and therefore would not add any value. As regard legal effects, it would seem that an IPR multilateral register clearly must imply multilateral protection and this should be the key element in establishing such a register. However, the U.S.-led Proposal is limited to creating a record rather than a true registration. The system does not provide for a mechanism to filter out names that should not be protected and, therefore, risks creating more confusion than clarity. The proposal is silent on the need for elements of proof, for the assessment of eligibility, or for an opposition procedure elements which seem indispensable in the framework of an IPR register. Under this approach, it is impossible to ensure that terms that do not meet the provisions of Articles 22.1 or 24.9, or which fall under one of the exceptions provided for in Article 24, are denied eligibility. The U.S.-led Proposal also does not establish procedures to resolve possible litigation, an indispensable procedure for any future multilateral register. The great uncertainty regarding legal effects may thus increase litigation and, consequently, administrative costs. It also does not provide for any monitoring mechanism which requires national authorities to refer to the lists of GIs on the database. As a result, these national authorities will not know whether to rely on the information included in the system when making a determination on the protection of a GI. For all these reasons, it is difficult to understand how the mandate to facilitate the protection of GIs established in Article 23.4 would be fulfilled through this system.

As to the participation in the system, the minimalist approach group also does not provide for a system with a truly multilateral character. In reality, it is unclear whether nonparticipating Members would be bound to give protection according to Article 23. If nonparticipating Members were not bound, the mandate to facilitate GIs protection as mandated in Article 23.4 - would be undermined. The literal meaning of the U.S.-led Proposal seems based on a political commitment without legal force: authorities would be bound to refer to the register, yet the register gives rise to no national legal commitment. Assuredly, Article 23.4 calls for more ambitious action than this proposal offers. The proposal concentrates on the first part of the job, namely the establishment of a notification system, while the register would simply compile participating Members information. As of this writing it is unclear whether this would satisfy the requirement of producing legal effects that registration inherently should entail in the context of IPR66. If transparency alone is the only advantage offered by the proposed U.S.-led system, it might not be sufficient to justify its costs. To facilitate GIs legal protection under Article 23.4, a multilateral system sh ould help administering bodies implement, and producers and consumers avail themselves of, legal protection. To respond to this mandate, it seems essential after so many years of negotiations to foresee at least that, beyond the simple obligation to consult a source of information, WTO Members should provide some clear assurances that the national authorities responsible for GIs - judges, trademark examiners or other authorities would have the obligation not only to consult the information in the register but also to take due account of this information when making decisions by giving it all the necessary weight. By contrast, the proposal sponsored by the EU could in this authors view help to facilitate GIs protection, as Article 23.4 TRIPS Agreement prescribes. This could occur even thought it has significantly reduced their initial claims in order to achieve the desired consensus. This proposal struck a balance between different interests and would be the appropriate tool towards a register which would truly facilitate GI protection, and not duplicate what would already be available on the Internet system. The proposal would not entail any automatic protection, would not oblige WTO Members to change their protection system and would not generate excessive administrative costs and burdens. Possibly, these are the reasons which make this proposal to enjoy nowadays the support of two thirds of the WTO Members.

INDIAS ROLE IN FORMING WTO

When the Uruguay round of GATT talks was in progress during early 1990s, Indian economy was ailing and was totally out of track. Under this compelling situation, India adopted new economic reforms (NERS) in 1991 based on Rao-Manmohan Model as a crisis driven strategy. Macro Economic Stabilization (MES) which covered reforms in monetary policy, fiscal policy and external sector was brought to provide immediate relief to ailing economy. But, structural reforms, also called SAP(Structural Adjustment Programmes), was meant for long term reform process which covered components of industrial policy reform, PSU reform, financial sector reform and trade & capital flow reforms. Then crisis-driven reforms has now reached to consensus driven under second generation of our reform policies. These changes in Indian economy based on LPG gave rise to a new market economy that brought growth and development in India. In this context, the emergence of WTO as multilateral trade body to make trade friendly environment at the global level and Indian attachment to this body could be understood. India one of the founder member of WTO, had its own expectations as well as reservations about the new economic order. While it unleashed great opportunities for agriculture and textiles sectors by improving their access to developed countries (as provided by AoA-Agreement on Agriculture and phasing out of MFA- Multi Fiber Agreement), it has some grey areas in the form of provisions for patent regime and services sector. As the events gradually unfolded, India, like other developing countries recognized that the rules of the game were not favorable to them and they must play on active role within the permissible limits to minimize the damage. In the last decade, our economic agenda and the policies to be pursued have been largely shaped by the WTO commitments. India adopted the process of globalization and WTO rulings as a facet of structural reforms. It brought devaluation in currency in 1991 and also adopted convertibility system in Indian rupees in different stages. Trade and current account have been made fully convertibility regime, though cautious and as a long term objective. Various steps have been taken towards import liberalization in India, for example, de-licensing, de-canalization &expansion of OGL (open general license),removing quantitative restriction, lowering peak custom rate, etc,. India has also adopted a very liberal policy towards foreign capital to attract direct foreign investment and portfolio investment. Insurance and print media have been

opened for private competition. India has made following changes in the economy as mandated by WTO. Quantitative restrictions have been completely phased out in 2000-01 and only the tariff structure remains which itself has been lowered considerably, with 67% of the tariff lines being bound. Patent law has been reformed with amendment of Patent act (2006). It provides for product patent in pharmaceutical and farm products. Under the TRIMS agreement, restrictions on entry of foreign investment and conditions upon various aspects have been removed and relaxed. Except a few sectors, FDI is being allowed upto 100% though automatic route and Indian companies are also free to invest abroad. Under the GATS (General Agreement on Trade in Services), India has made commitment in 33 activities where Foreign Service providers are allowed to enter keeping in view national interests. Indias legislation on Custom Valuation rules, 1998 has been amended to bring it in conformity with the provisions of WTO agreements on implementation of article VII of GATT 1994 and the Customs Valuation Agreement. A survey of last 15 years since adoption of new economic reforms and especially after joining WTO, it is now clear that we have done well and still a lot of scope remained for further development. The process of globalization and the provision of WTO have had, no doubt, some important positive implications. Under this process, a platform has been created for different types of multilateral agreements. Multilateral regulation and discipline have been established & imposed and up to certain extent, trade friendly environment has been created. Disputes are being solved & managed and trading activities are getting protection. India is also getting the benefits of this emerging trade friendly environment. Indian exports, especially exports of agricultural good, have been increased. The Doha development Agenda, though passing through hard times; is built on the long term objective of the AOA to establish a fair and a market oriented trading system. India could be highly advantaged with DDA. During the ongoing negotiations, India and other developing countries have sought a special safeguard mechanism (SSM) for addressing situations of import surges or swings in international prices of agricultural products. Other measures concerning developing countries in the WTO agreements include:

Extra time for developing countries to fulfill their commitments (in many of the WTO agreements) Provisions designed to increase developing countries trading opportunities through greater market access (e.g. in textiles, services, technical barriers to trade) Provisions requiring WTO members to safeguard the interests of developing countries when adopting some domestic or international measures (e.g. in anti-dumping, safeguards, technical barriers to trade)

Provisions for various means of helping developing countries (e.g. to deal with commitments on animal and plant health standards, technical standards, and in strengthening their domestic telecommunications sectors). The WTO agreements, which were the outcome of the 198694 Uruguay Round of

trade negotiations, provide numerous opportunities for developing countries to make gains. Further liberalization through the Doha Agenda negotiations aims to improve the opportunities. Among the gains are export opportunities. They include: Fundamental reforms in agricultural trade Phasing out quotas on developing countries exports of textiles and clothing Reductions in customs duties on industrial products Expanding the number of products whose customs duty rates are bound under the WTO, making the rates difficult to raise Phasing out bilateral agreements to restrict traded quantities of certain goodsthese grey area measures (the so-called voluntary export restraints) are not really recognized under GATT-WTO.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Deepika ShampooДокумент8 страницDeepika ShampooThilaga Senthilmurugan100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- BackgroundДокумент12 страницBackgroundThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- KaluriДокумент5 страницKaluriThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- AccountДокумент14 страницAccountThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Bharti Junkfoodpresentation 100824050332 Phpapp01Документ29 страницBharti Junkfoodpresentation 100824050332 Phpapp01Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Main FeaturesДокумент4 страницыMain FeaturesThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- No59 38PA SinghДокумент18 страницNo59 38PA SinghThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Interbank Mobile Payment ServiceДокумент24 страницыInterbank Mobile Payment ServiceThilaga Senthilmurugan100% (1)

- 05 N156 33679Документ18 страниц05 N156 33679Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- BackgroundДокумент6 страницBackgroundThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Hotel in A 1965 Nivel by Arthur HaileyДокумент1 страницаHotel in A 1965 Nivel by Arthur HaileyThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Shoppers StopjazzДокумент15 страницShoppers StopjazzThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Eco Project 2014Документ7 страницEco Project 2014Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- AccountДокумент14 страницAccountThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Budgets (Matter)Документ38 страницBudgets (Matter)Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Enforcing Human Rights Through The WTO A Critical Appraisal PDFДокумент49 страницEnforcing Human Rights Through The WTO A Critical Appraisal PDFThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Finalprojet (Intro)Документ80 страницFinalprojet (Intro)Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- PDF 1152Документ32 страницыPDF 1152Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Budgets (Matter)Документ38 страницBudgets (Matter)Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Advanced Cost Accounting-FinalДокумент154 страницыAdvanced Cost Accounting-FinalThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Impact Off FDi in Retail On Sme Sector SurveyДокумент10 страницImpact Off FDi in Retail On Sme Sector Surveysudheer1112Оценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- 19722ipcc CA Vol1 Cp3Документ0 страниц19722ipcc CA Vol1 Cp3Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- FDI in Indian Retail Sector Analysis of Competition in Agri-Food SectorДокумент57 страницFDI in Indian Retail Sector Analysis of Competition in Agri-Food SectorTimur RastomanoffОценок пока нет

- 19722ipcc CA Vol1 Cp3Документ0 страниц19722ipcc CA Vol1 Cp3Thilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Impact Off FDi in Retail On Sme Sector SurveyДокумент10 страницImpact Off FDi in Retail On Sme Sector Surveysudheer1112Оценок пока нет

- India Anti-Money Laundering Survey 2012: ForensicДокумент32 страницыIndia Anti-Money Laundering Survey 2012: ForensicThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- Chapter 16 Labour Cost ControlДокумент14 страницChapter 16 Labour Cost ControlThilaga Senthilmurugan100% (5)

- Money Laundering: Methods and MarketsДокумент0 страницMoney Laundering: Methods and MarketsThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Aml-What You Must KnowДокумент2 страницыAml-What You Must KnowThilaga SenthilmuruganОценок пока нет

- 2013 Jessup Best MemorialДокумент65 страниц2013 Jessup Best MemorialEmil Angelo C. Martinez0% (1)

- Erie Railroad at Seventy-FiveДокумент304 страницыErie Railroad at Seventy-FiveAmerican Enterprise InstituteОценок пока нет

- Hart's Concept of Law Analyzes Relation Between Law, Coercion and MoralityДокумент5 страницHart's Concept of Law Analyzes Relation Between Law, Coercion and MoralityKumar NaveenОценок пока нет

- Time, History and International LawДокумент264 страницыTime, History and International LawFabian Jacquin100% (2)

- GuidanceДокумент98 страницGuidancePaul DruryОценок пока нет

- ICJ Case on Evacuation During Influenza OutbreakДокумент25 страницICJ Case on Evacuation During Influenza OutbreakNorman Kenneth SantosОценок пока нет

- Truth Seeking Elements of Creating An Eff Ective Truth CommissionДокумент78 страницTruth Seeking Elements of Creating An Eff Ective Truth CommissionGlobal Justice Academy100% (1)

- 25 Crime Manual Vol IIДокумент691 страница25 Crime Manual Vol IIammaiapparОценок пока нет

- Hizon Notes - Public International Law (Jasmin Micah Jabal - S Conflicted Copy 2014-08-09)Документ53 страницыHizon Notes - Public International Law (Jasmin Micah Jabal - S Conflicted Copy 2014-08-09)Jimcris Posadas HermosadoОценок пока нет

- Legal Consequences For States of The Continued Presence ofДокумент4 страницыLegal Consequences For States of The Continued Presence ofJohnKyleMendozaОценок пока нет

- Md2 Timewarp HartДокумент3 страницыMd2 Timewarp HartNishant KumarОценок пока нет

- Intro Scope Nature and Evolution of International LawДокумент2 страницыIntro Scope Nature and Evolution of International LawAli WassanОценок пока нет

- PIL ProjectДокумент11 страницPIL ProjectSanchit AsthanaОценок пока нет

- The History and Nature of International LawДокумент32 страницыThe History and Nature of International Lawschafieqah50% (4)

- Public International LawДокумент3 страницыPublic International LawRamon MuñezОценок пока нет

- GR No. L-5. September 17, 1945 DigestДокумент2 страницыGR No. L-5. September 17, 1945 DigestMaritoni Roxas100% (3)

- Jurisdiction of States in Public International LawДокумент3 страницыJurisdiction of States in Public International LawJoe PolitixОценок пока нет

- 2012 Bar Questions in Public International LawДокумент20 страниц2012 Bar Questions in Public International LawJoy RaguindinОценок пока нет

- Applicant 2008 - D M Harish Memorial Moot CompetitionДокумент40 страницApplicant 2008 - D M Harish Memorial Moot CompetitionNabilBariОценок пока нет

- ICC Parallel State and Arbitral Procedures in International ArbitrationДокумент11 страницICC Parallel State and Arbitral Procedures in International ArbitrationOluwatobi OgunfoworaОценок пока нет

- Legal MemorandumДокумент2 страницыLegal MemorandumArrenz Joseph B. MagnabihonОценок пока нет

- Vattel's The Law of Nations online resource guideДокумент1 страницаVattel's The Law of Nations online resource guideWithout the UNITED STATES/DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (Luke 11:52)100% (1)

- The Application of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law To International OrganisationsДокумент105 страницThe Application of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law To International OrganisationsGlobal Justice Academy100% (2)

- 11 Rhetoric and RageДокумент51 страница11 Rhetoric and Ragehaseeb_javed_9Оценок пока нет

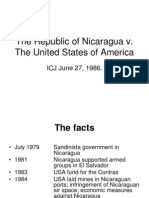

- Nicaragua v USA at ICJ Rules on Customary International LawДокумент23 страницыNicaragua v USA at ICJ Rules on Customary International LawAinnabila RosdiОценок пока нет

- Razon Vs TagitisДокумент51 страницаRazon Vs TagitisJosh CabreraОценок пока нет

- The Rights of Refugees Under International Law PDFДокумент1 238 страницThe Rights of Refugees Under International Law PDFAlina RizviОценок пока нет

- PHAP V Duque PDFДокумент3 страницыPHAP V Duque PDFIanBiagtanОценок пока нет

- Jurisdiction in Cyberspace - A Theory of International SpacesДокумент36 страницJurisdiction in Cyberspace - A Theory of International SpacesratnapraОценок пока нет

- PIL NotesДокумент2 страницыPIL NotesZazza SimbulanОценок пока нет

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationОт EverandThe Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (1569)

- You Sound Like a White Girl: The Case for Rejecting AssimilationОт EverandYou Sound Like a White Girl: The Case for Rejecting AssimilationРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (44)

- LatinoLand: A Portrait of America's Largest and Least Understood MinorityОт EverandLatinoLand: A Portrait of America's Largest and Least Understood MinorityОценок пока нет

- Reborn in the USA: An Englishman's Love Letter to His Chosen HomeОт EverandReborn in the USA: An Englishman's Love Letter to His Chosen HomeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (17)

- A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a CommunityОт EverandA Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a CommunityОценок пока нет

- They Came for Freedom: The Forgotten, Epic Adventure of the PilgrimsОт EverandThey Came for Freedom: The Forgotten, Epic Adventure of the PilgrimsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (11)

- City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New YorkОт EverandCity of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New YorkРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (23)