Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Book Review, "The Thrill Makers"

Загружено:

jalyon6Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Book Review, "The Thrill Makers"

Загружено:

jalyon6Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

93 | VOLUME X, SPRING 2013

cultural trauma has made remembering the black past in all its complexity, too painful, creating a festering wound that will not heal, a shame that burns and scars the soul (12). Black Gotham is Petersons ambitious attempt to not only preserve memories of past oppression and resistance, but also to create new, actionable memories for future generations. Peterson emerges as the chief protagonist in Black Gotham, which may frustrate readers who favor a traditional academic approach that avoids first person narration. Nevertheless, Peterson comes across as a diligent historical detective journeying through the murky corridors of this nations past in search of truth and justice, and, personally, for her own unique place in America. Michael Edward Brandon is a PhD candidate at the University of Florida, studying history.

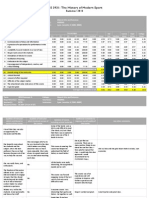

Jacob Smith. The Thrill Makers: Celebrity, Masculinity and Stunt Performance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. Reviewed by Jennifer A. Lyon Before Felix Baumgartner became the first human to break the sound barrier by skydiving from space in 2012, before the X-Games, and even before Evel Knievel ramped a motorcycle over 50 stacked cars in 1973, there was a long-standing tradition of performers seeking glory through dangerous public spectacles in the United States. Newspapers trumpeted the feats of nineteenth-century daredevils like Sam Patch, who dove headfirst off Niagara Falls in 1829, and Steve Brodie, who jumped from atop the Brooklyn Bridge in 1886; yet, despite notoriety during their own lifetimes, Jacob Smith explains, these performers have largely been forgotten. It is his intention to recover the history of stunt performance and its impact on society in

Book Reviews| 94

The Thrill Makers: Celebrity, Masculinity and Stunt Performance. Far from trivial exploits, he argues that these stunts played an important role in shaping turn-of-thecentury definitions of manhood, popular culture, and the construction of modern media spectacle and celebrity (2). Presenting each chapter as a case study, Smith examines four types of performers: bridge jumpers, human flies, lion tamers, and stunt pilots. Arguably, Smith is at his best in the first two chapters, as he details how bridge jumpers and human fliesthose who climbed buildings without safety devicesevolved out of earlier performance traditions. Bridge jumping, for example, represented a continuation of public spectacle alongside canals, docks, and waterfronts in industrial cities, while human flies emerged from stage and circus traditions, like that of the ceiling walker who performed upside down using suction-cup shoes. But while ceiling walkers were often teenage girls (the suction cups had a weight limit), human flies were men who took to the new urban landscape and performed on spaces not associated with entertainment: skyscrapers. Here theatric climbing was fused with common labor as many performers came from the ranks of those who built and repaired smokestacks, churches, and other tall monuments. As Smith explains, workmen became showmen, and labor became entertainment. Smith goes on to draw connections between these new types of spectacle and changing notions of masculinity in the industrial city. Echoing the work of historians like Elliott Gorn and Christine Stansell, Smith explains that performers and spectators were drawn to activities that counteracted the dehumanizing aspects of the industrial workplace and urban life. Human flies brought imposing skyscrapers down to human scale, he explains, while bridge jumpers transformed monoliths of modern engineering into vehicles for the creation of self (187). With regard to masculinity, Smith argues that thrill makers represented manly independence, with their stunts

95 | VOLUME X, SPRING 2013

reassuring men that meaningful and traditional masculine work could be found (188-89). In the second half of the book Smith specifically discusses lion tamers and aeronauts, but more broadly examines how these thrill makers were increasingly marginalized. New laws criminalized scaling buildings or jumping off bridges, reformers pursued lion tamers for animal cruelty, and industry-friendly legislation grounded trick pilots. The critical turning point, however, was the growth of modern cinema. As motion pictures became the dominant form of entertainment, stunts were repackaged for the silver screen and the performers themselves actively marginalized by the media in favor of movie stars. If they did find work in film, they were relegated to anonymous stunt double positions where they received little compensation and no accolades. A crowd of 45,000 gathered to see Harry Gardiner climb an Indiana courthouse in 1916, but a generation later thrill makers were anonymous and expendable. This invisibility would continue to characterize Hollywood. Indeed, we can name the actors who have played James Bond, but are less likely to know the faceless men who actually performed his stunts. In this way, Smith succeeds in his goal of making the reader see double. That is, to appreciate the history and labor of the unnamed stunt double (184). As a full-length text, The Thrill Makers is best suited for graduate-level seminars. Smiths research is impressive, and he maintains an engaging narrative through chapters one and two. However, the extensive use of film theory in later chapters hampers the books readability. In certain areas it feels as though Smith overreaches to fit stunt performance within existing theoretical frameworks, rather than letting the sources and historical actors speak for themselves. Still, this reviewer would like to see Smith follow in Kathy Peisss footsteps by extracting a chapterlength piece suitable for the undergraduate classroom. Smiths discussion of stunt performance, labor, and masculinity in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth

Book Reviews| 96

centuries has a high potential to engage students. Both undergraduates and popular audiences are sure to be interested in Smiths stories of steeple flyers, who attached ropes to tall cathedral steeples, strapped boards to their chests, and then slid headfirst to the ground while shooting pistols or blowing trumpets, or that of tightrope walker Chevalier Blondin who crossed Niagara Falls in the 1850s with a sack over his head, dressed as a monkey, pushing a wheelbarrow, carrying his manager on his back, and with baskets on his feet (42). Fascinating vignettes like these ensure The Thrill Makers will reach all audiences. Jennifer A. Lyon is a PhD candidate at the University of Florida, studying history.

Henry Wiencek. Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012. Reviewed by Jordan Vaal In Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves, Henry Wiencek offers new insight into the debate surrounding Thomas Jefferson and slavery. Wienceks book examines closely Jeffersons actions between the early 1780s and the late 1790s, when he shifted away from advocating for the eradication of slavery and ceased most of his efforts towards emancipation. According to Wiencek, Jefferson justified his refusal to act by creating theories of racial inferiority and by claiming that the United States was not ready for emancipation. Many scholars have examined Thomas Jeffersons relationship with slavery and with his own slaves, justifying his oppressive behavior by arguing that he was a product of his time. By Jeffersons era, slavery was a longestablished institution, deeply connected with all aspects of

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Master-Slave DialecticДокумент16 страницThe Master-Slave DialecticGoran StanićОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Gregory Denis Ecclesiastic Deed PollДокумент4 страницыGregory Denis Ecclesiastic Deed PollDivine Echo100% (41)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Trojan Women Final TextДокумент71 страницаTrojan Women Final TextDorian GreyОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- American Literature Revised Edition PDFДокумент179 страницAmerican Literature Revised Edition PDFAugusto Chocobar100% (1)

- Christina Sharpe - in The Wake-On Blackness and Being - Chap1Документ37 страницChristina Sharpe - in The Wake-On Blackness and Being - Chap1Andiara Dee Dee100% (1)

- Level 4-Gone With The Wind Part OneДокумент78 страницLevel 4-Gone With The Wind Part OneSunbul NurgeldiyevaОценок пока нет

- Huck and Jim's Quest for Freedom Against SlaveryДокумент2 страницыHuck and Jim's Quest for Freedom Against SlaveryProtim SharmaОценок пока нет

- Two Concepts of LibertyДокумент11 страницTwo Concepts of LibertyAmit Joshi100% (1)

- Freedom - Concept PaperДокумент6 страницFreedom - Concept Paperseph091592100% (3)

- Evaluations: AMH 2020, Spring 2012Документ8 страницEvaluations: AMH 2020, Spring 2012jalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Evaluations: AMH 2020, Fall 2012Документ4 страницыEvaluations: AMH 2020, Fall 2012jalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Teaching Evaluations: HIS 3931Документ2 страницыTeaching Evaluations: HIS 3931jalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Milbauer EssayДокумент15 страницMilbauer Essayjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- History: Jennifer A. Lyon Graduate Teaching Award Application, Teaching PhilosophyДокумент1 страницаHistory: Jennifer A. Lyon Graduate Teaching Award Application, Teaching Philosophyjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Book Review, "Moonshiners and Prohibitionists"Документ3 страницыBook Review, "Moonshiners and Prohibitionists"jalyon6Оценок пока нет

- AMH 2020 - Extra Credit Info SheetsДокумент8 страницAMH 2020 - Extra Credit Info Sheetsjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- AMH 2020 - Essay Info SheetsДокумент5 страницAMH 2020 - Essay Info Sheetsjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- UF Faculty Evaluations - Spring 2012Документ9 страницUF Faculty Evaluations - Spring 2012jalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Amh 2020: History Since 1877: Instructor: Jennifer A. LyonДокумент7 страницAmh 2020: History Since 1877: Instructor: Jennifer A. Lyonjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Teaching EvaluationsДокумент18 страницTeaching Evaluationsjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- UF Faculty Evaluations - Fall 2012Документ4 страницыUF Faculty Evaluations - Fall 2012jalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Folio HD Milbauer EssayДокумент15 страницFolio HD Milbauer Essayjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Folio HD Milbauer EssayДокумент15 страницFolio HD Milbauer Essayjalyon6Оценок пока нет

- Slavery and The Idea of ProgressДокумент9 страницSlavery and The Idea of ProgressScott RankОценок пока нет

- A Dance of The Forests Analysis: Wole SoyinkaДокумент8 страницA Dance of The Forests Analysis: Wole SoyinkaSaima yasinОценок пока нет

- Alexander, Bonner, Hyslop, Van Der Walt - Labour Crossings in Eastern and Southern AfricaДокумент104 страницыAlexander, Bonner, Hyslop, Van Der Walt - Labour Crossings in Eastern and Southern AfricaredblackwritingsОценок пока нет

- Edited Rhetorical Analysis EssayДокумент2 страницыEdited Rhetorical Analysis Essayapi-491887992Оценок пока нет

- Case Study 1-Business EthicsДокумент3 страницыCase Study 1-Business EthicsDabhi MehulОценок пока нет

- William H. Chenery - The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in The War To Preserve The Union, 1861-1865 (1898)Документ442 страницыWilliam H. Chenery - The Fourteenth Regiment Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored) in The War To Preserve The Union, 1861-1865 (1898)chyoungОценок пока нет

- Sojourner Truth TimelineДокумент1 страницаSojourner Truth TimelineBrandi ThompsonОценок пока нет

- A Biography of Abraham LincolnДокумент2 страницыA Biography of Abraham LincolnFrances Mckee100% (1)

- Ancient Rome: Causes For The Fall of The Roman EmpireДокумент3 страницыAncient Rome: Causes For The Fall of The Roman EmpireSavannah ByersОценок пока нет

- Levi Bryant - Politics and Speculative RealismДокумент7 страницLevi Bryant - Politics and Speculative RealismSoso ChauchidzeОценок пока нет

- Lincoln's Second Inaugural AddressДокумент2 страницыLincoln's Second Inaugural AddressVictoria DohertyJarvisОценок пока нет

- Anna Kingsley Book ReviewДокумент3 страницыAnna Kingsley Book ReviewrenОценок пока нет

- Slavery in Ancient Greece.Документ7 страницSlavery in Ancient Greece.Rajat Pratap100% (1)

- APUSH Review: Key Terms, People, and Events from Periods 1-4Документ35 страницAPUSH Review: Key Terms, People, and Events from Periods 1-4Cedrick EkraОценок пока нет

- United States History and Government Regents Review PacketДокумент30 страницUnited States History and Government Regents Review PacketJuliAnn Immordino100% (1)

- Assignment #2: Rizal Technological University Bachelor of Science in Accountancy SY 2020-2021Документ2 страницыAssignment #2: Rizal Technological University Bachelor of Science in Accountancy SY 2020-2021merryОценок пока нет

- Review On in Praise of IdlenessДокумент2 страницыReview On in Praise of IdlenessShodan ArОценок пока нет

- Assertion JournalsДокумент3 страницыAssertion Journalsapi-252008277Оценок пока нет

- Dwnload Full Fundamental Accounting Principles 23rd Edition Wild Test Bank PDFДокумент35 страницDwnload Full Fundamental Accounting Principles 23rd Edition Wild Test Bank PDFexiguity.siroc.r1zj100% (10)

- The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803 1Документ136 страницThe Philippine Islands, 1493-1803 1Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- America A Family Matter - Gould, Charles Winthrop, 1849-1931Документ231 страницаAmerica A Family Matter - Gould, Charles Winthrop, 1849-1931wealth10Оценок пока нет