Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tourism Theory and The Earth

Загружено:

Jessi ArévaloИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tourism Theory and The Earth

Загружено:

Jessi ArévaloАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp.

155170, 2012 0160-7383/$ - see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in Great Britain

www.elsevier.com/locate/atoures

doi:10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.009

TOURISM THEORY AND THE EARTH

Martin Gren Icelandic Tourism Research Centre, Iceland University of Gothenburg, Sweden Edward H. Huijbens University of Akureyri, Iceland

Abstract: Given that tourism is an earthly business, why is it that the Earth rarely explicitly appears in tourism studies and tourism theory? In an attempt to grapple with this paradox, this paper seeks to contribute to a conceptual re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory by probing some theoretical obstacles and possibilities. The paper demonstrates how the Earth has been conceptually erased in tourism theory by a privileging of the mapping of tourism and tourists onto the reference plane of the social. As an alternative the paper seeks to provide a geo-philosophically informed conceptualisation of the Earth as a primary plane of reference of which tourism is a particular form of de/re-territorialisation. Keywords: tourism theory, the Earth, Deleuze, the social, de/re-territorialisation, geo-philosophy. 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION Tourism and tourists have long since been investigated in tourism studies through concepts like location, site, landscape, region, place, and space. A more recent interest in tourism mobilities (Sheller & Urry, 2004) at various geographical scales further suggests that tourism scholars seem to acknowledge that tourism is essentially a geographical activity (Lew, 2001, p. 113). In addition, tourism is also part of policies and practices, notably sustainable development (Davos Declaration, 2007; Holden, 2008; Saarinen, 2006) and an evolving politics of climate change (Dennis & Urry, 2009; Giddens, 2009; IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), 2007; Scott, 2011; Weaver, 2011), concerning our common future on the Earth. To this

Martin Gren holds a PhD in Human geography since 1994. Appointed as lecturer in human geography in Sweden 1995 and as researcher/reader in Iceland 2007. Research interest: tourism theory and the Earth. Currently working on researching images and an introductory textbook to (earthly) tourism studies (Researcher at the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre, Borgum v/Norurslo , Akureyri, Iceland (IS-600) Email <Martin.Gren@conservation.se.gu>). Edward H. Huijbens holds a PhD in Human geography since 2006, the same year he was appointed the director of the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre along with a post at the University of Akureyri. Research interests are in cultural studies, tourism and innovation and regional marketing (Director of the Icelandic Tourism Research Centre, Reader at the Department of Business and Science, University of Akureyri, Borgum v/Norurslo , Akureyri, Iceland (IS-600) Email <edward@unak.is>). 155

156

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

could be added numerous case studies on tourists and tourism in particular locations and destinations. Given this geographical understanding of tourism in theory and practice, meaning that it is fundamentally an earthly business, we nd it rather peculiar and paradoxical that the Earth itself is in fact practically never explicitly theorised in tourism studies. In response, the aim of this paper is to contribute to a conceptual re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory by probing some theoretical obstacles and possibilities. This aim is not to be understood as an attempt to develop a denite theoretical account of what the Earth is or ought to be in tourism theory. We are certainly not implying that the Earth is a ready-made object, an it out there on which tourism merely takes place. In our understanding there is simply no single referential essence of a real Earth to be found. As Lefebvre once put it; For all that the earth may become, Mother Earth, cradle of life, symbolically sexual ploughed eld, or a tomb, it will still be the earth (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 141). Hence, the Earth is a concept that can be understood in a number of different ways, also in tourism studies. Consequently, we believe that there are several possibilities of re-cognising the Earth in tourism theory, and we wish our own attempts here to be read as an invitation to further probe real possibilities as well as virtual potentials thereof. As for what follows, we begin our earthly endeavour by problematising tourism studies as a social science. We claim that much of current theorising in tourism offers rather one-sided comprehensions of tourism as a predominantly social phenomenon dependent upon one of the most signicant achievements of social theory: the fabrication of the social as a separate plane of reference. This one-sidedness we take to task, gradually introducing theoretical strands that put question marks around such theorisations of the social. Foremost thereof is actor-network theory (Latour, 2005), but we add non-idealist versions of post-structuralism that come with a material twist (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988), which some authors have formulated as geo-philosophy (Bonta & Protevi, 2004; Deleuze & Guattari, 1988; Deleuze & Guattari, 1994; Gren & Tesfahuney, 2004). We end the paper by summing up our attempts to contribute to a conversation in tourism studies about a conceptual re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory. TOURISM THEORY: FROM THE SOCIAL TO THE EARTH Some readers may well consider our attempt to ll in the blind spot of the Earth in tourism theory to border on the obvious or to be, at best, a trivial pursuit, or perhaps an internal affair for tourism geography. Is not the corpus of tourism studies already lled with several mappings of precisely earthly tourist places and tourism spaces? Yet, as much as numerous case studies frequently make use of concepts like space and place, they are not sufcient in providing a ground for a theoretically informed re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory. On closer inspection we draw the tentative conclusion that in tourism

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

157

studies both tourism and tourists have, to a considerable extent, been conceived of and theorised rst and foremost as social phenomena. Accordingly, tourism has often implicitly or explicitly been comprehended as something that occurs in society, or in places and through spaces conceived of as socially constructed. In the same way tourists have been conceptualized as social subjects that live their lives inside their own social world(s). There is nothing wrong with such theorising, but it is an obstacle when it comes to re-cognising the Earth. As Latour put it in his Plea for Earthly Sciences:

Who are you really, Earthlings, to believe that you are the ones adding relations by the sheer symbolic order of your mind, by the projective power of your brain, by the sheer intensity of your social schemes, to a world entirely devoid of meaning, of relations, of connections?! Where have you lived until now? Oh I know, you have lived on this strange modernist utterly archaic globe; and suddenly (under crisis) you realize that all along you have been inhabiting the Earth (Latour, 2007, p. 8).

Following Latour, it seems that the modern constitution (Latour, 1993) has very much ruled out the possibility of a specic slot in social science for the Earth. What comes out of the modern grand narrative, or washing machine, is either society or nature, (the social or the material). Consequently, the Earth is in social science conceptually located as too close to a nature, signied as the external other of the social, and too intimately related to the domain of tangible matter. In effect, this ontology of the social results in the veritable erasure of theorisations and conceptualisations of the Earth in social science. The social thus conceived is, in our terminology, the plane of reference for understanding and explaining whatever phenomena in social science. It is the privileging of that reference plane in tourism studies that we would like to problematise. By invoking instead the reference plane of the Earth we are, however, not trying to reify the Earth as the foundational subject of study, but rather illustrate one other conceptual possibility. Tourism Studies as a Social Science Within tourism studies an orientation towards the social is unsurprising, not least since [o]ver the past decades knowledge about tourism has been developed rapidly, notably through the work of social scientists (Stergiou, Airey, & Riley, 2008, p. 632). Even though social scientists may have been belatedly drawn to the study of tourism, things have now changed so that in the last three decades tourism became a respected specialty in sociology, anthropology, geography, political science, economics and some other disciplines (Cohen, 2008, p. 330). Tourism scholars themselves now commonly consider tourism studies to be a social science. Below we demonstrate how in tourism publications, as well as educational curricula, tourism (and tourists) is formulated as social phenomena.

158

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

A scanning of a couple of key texts in tourism studies seems to verify a tendency to adopt variations of the basic assumption that tourism is a reection of society (Sharpley, 1994, p. 24). The central thesis of MacCannells classic The Tourist, a study in the sociology of leisure in the context of modernity, holds the expansion of modern society to be intimately linked in diverse ways to modern mass leisure, especially to international tourism and sightseeing (MacCannell, 1999/1976, p. 3). According to MacCannell, [t]ouristic consciousness is motivated by its desire for authentic experiences (MacCannell, 1999/1976, p. 101) and the eventual shape and stability of tourist attractions are socially determined (MacCannell, 1999/1976, p. 132). Another key text, Urrys The Tourist Gaze, is concerned with how in different societies and especially within different social groups in diverse historical periods the tourist gaze has changed and developed (Urry, 2002/ 1990, p. 1). Drawing upon the Foucauldian notion of the medical gaze, Urry claims that the tourist gaze is as socially organised and systematised as is the gaze of the medic (Urry, 2002/1990, p. 1). A recent illustration of how tourism and tourists are similarly mapped onto the reference plane of the social can be found in a book titled: Landscape, Tourism, and Meaning. Although landscape is often understood as a geographical concept, thus close to the Earth, the attempt to retheorise tourism is here done by drawing on the social construction of meaning in the landscape and by situating the study of tourism within the framework of social theory (Knudsen, Metro-Roland, Soper, & Greer, 2008, p. 1). In other words, the tourism landscape becomes conceived of as the end result of a process of social construction (Knudsen et al., 2008, p. 5). One can then say, in the vocabulary used here, that the landscape becomes a reference plane of and for the social rather than a reference plane of the Earth. For us these brief examples illustrate a broader principal of the social framing of tourism studies and seem to verify that a standard denition or interpretation of tourism /. . ./ is usually inuenced by a social science perspective (e.g., a geographical, economic, political or sociological approach) (Page & Connell, 2006, p. 11). Yet, this relationship between tourism studies and social science has also been the object of considerable concern. There are those that have asserted that the social science perspective in tourism studies is still relatively underdeveloped compared to other areas of inquiry (Holden, 2005, p. 1). With regards to tourism theory it is, for example, claimed that [t]o date no theoretical construct or theory which explain the development and internal dynamic of tourism as a process of global economic and social change have been developed (Page & Connell, 2006, p. 9). Mirroring these concerns are those voices proclaiming that tourism studies should be of wider relevance to the social sciences (Larsen, Urry, & Axhausen, 2006, p. 245). Instead of being just an importer of social science ideas, or a convenient provider of an empirical eld for others to harvest, tourism studies should also be an exporter of knowledge of the social. As expressed by Shaw and Williams (and echoed in Pons, 2003, p. 48):

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

159

[W]e do not see tourism as just an importer of social-science ideas. Instead, we see tourism as being deeply embedded in all aspects of life. As such, the understanding of tourism contributes to the understanding of society, and in this way tourism researchers should actively seek to contribute to debates in the other social sciences (Shaw & Williams, 2004, p. 276).

This suggests that, in order to contribute to the understanding of society in the other social sciences, researchers and scholars in tourism studies need to address that studies so far have mostly neglected issues of sociality and copresence and overlooked how much tourism is concerned with (re)producing social relations (Larsen et al., 2006, p. 245). Given the emergence of this more topologically complex social spatiality of tourism, it thus becomes crucial to overcome mainstream research that still treats tourism as a predominantly exotic set of specialized consumer products that occur at specic places and times (Larsen et al., 2006, p. 245). This demands to challenge the old, but still common, view that tourism is created and occurs [only] in places and that [t]o be a tourist is to experience the world of tourism in places an experience that has become fundamental to that of human modernity (Lew, 2003, p. 121). Consequently, tourism can no longer easily be theoretically or conceptually framed by traditional dualistic divisions, like leisure-work, home-away, inauthentic-authentic, host-guest, ordinary-exotic, because tourism is no longer a temporary and unusual state of existence in a world otherwise organised by life at home and life at work (Franklin, 2003, p. 22). The discursive argument that seems to underpin the promotion of a more complex social spatiality of tourism is that tourism is not theorised as social enough. What is crucially important for us here is not the argument itself, nor how representative it is, but that the underlying ontology of a separately existing social realm in tourism theory, albeit now with more topological complexity added in between origin and destination, is rather assumed and left unquestioned. What is still lurking behind is an ubiquitous social, a taken-for-granted notion that tourism and tourist phenomena should be mapped onto the reference plane of the social. The Social and the Earth The ubiquity of the social comes in many guises. It may consist of a specic sort of phenomenon variously called society, social order, social practice, social dimension, or social structure (Latour, 2005, p. 3), or something similar like social system, social communication, or social space (Lefebvre, 1991; Luhmann, 1995). As Latour elaborates; the social as normally construed is bound together with already accepted participants called social actors who are members of a society (Latour, 2005, p. 247). In the words of one of the founders of modern social theory; [s]ocietal unication needs no factors outside its component elements, the individuals (Simmel, 1971, p. 7). Another of the founders, Durkheim, famously referred to

160

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

social facts as sui generis (of its own kind), meaning that they exist on their own and most often that they can only be explained by other social facts. In terms of tourism studies this social theorising implies that tourism and tourists must be primarily mapped on the reference plane of the social. Even in the sub-domain of tourism geography it has been possible to regard the almost standard earthly denition of tourism, activities of people travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment, as problematic because it fails to encapsulate any distinct sphere of social practice (Johnston, Gregory, Pratt, & Watts, 2000, p. 840). So, how come that not even geographers, coming from a discipline which means precisely earth writing (Gren, 1994) and which has a protracted record of published tourism scholarship dating back to the 1920s (Coles, Hall, & Duval, 2006, p. 296), have been unable to resist the temptation of framing their research as social and forget to maintain the Earth? Of crucial importance in explaining this forgetting is that this social ontology of social science and social theory is tantamount to a conceptual transformation of the Earth into various spatial objects like regions, landscapes and places. This erasure of the Earth has not only occurred through various systems of meaning, where notably cartographic reason has been involved (Gren, 2009; Gren, in press; Olsson, 2007), but paradoxically also through a wide range of processes on the planets surface that have included the physical prevention and enclosure of motion (Netz, 2004), and the development of various material technologies of time-space compression. In effect, these abstractions, or de-earthications, have not only contributed to the erasure of the concept Earth in social theory, but has brought forth the concept of space and further moved it, together with neighbouring concepts, towards the reference plane of the social (Doel, 1999). According to one quite dominant discourse, places and spaces are thus understood as social constructions, and the Earth at best appears in the guise of nature, environment or as a material frame for social action. We believe that this de-earthied social spatialism has become taken-for-granted in social science, in tourism theory, and somehow surprisingly even in human geography where space abounds but the Earth is quite absent. For our purposes, then, we need to locate a loophole in the reference plane of the social. Fortunately, we do not have to travel far as it can readily be found in tourism itself. Tourism Things, the Material and Non-human Agency A fracture, or loophole, in the social as a separate ontological domain can easily be seen through what we in everyday language refer to simply as things. As objects, artefacts, and whatever else of materialities there are, things are lent symbolic and discursive meaning, at the same time as they have a physical existence and presence independent of this. Things appear to us as intimately related to the privileging of the reference plane of the social, and have not received any

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

161

signicant recognition in tourism theory until recently. This is a paradoxical lacuna indeed since tourism is full of things and every single tourist in practice is surrounded by them. As spelled out by Franklin:

Tourism abounds with things, tourist things, and tourists are tied up in a world of tourist things for a considerable period of their time. And yet, if you read all the past and current text books on tourism, and make a list of all the really important explanations of tourism, the key concepts and theoretical developments, you will discover that these things are not held to be very signicant (Franklin, 2003, p. 97).

One principal reason why material things, such as aeroplanes, tickets, restaurants, museums, roads, or beverages have not been regarded as signicant in tourism theory and tourism studies is precisely because of the privileging of the reference plane of the social when projecting tourism phenomena. As a consequence, things have been either neglected or conceptually reduced to material objects, for example to those touristic objects like the Australian didgeridoo or the Mona Lisa, which tourists gaze upon in order to decode their socio-cultural meanings. Yet, there are ways of theorising tourism things other than reducing them to mute passive material objects with only extensive properties whose signicance should be measured and realized by the social (Baldacchino, 2010). As both more and less than mere matter, things may also be distinguished as signicant in themselves. Thus conceived, they do not only become equipped with a material agency that enables them to become active agents in the production of tourism (Franklin, 2003, p. 98). Deant of puried ontological classication, they can for example also become hybrids that transgress the division between the social and the physical. As Urry notes:

[M]ost signicant phenomena that the so called social sciences now deal with are in fact hybrids of physical and social relations, with no puried sets of the physical or the social. Such hybrids include health, technologies, the environment, the Internet, road trafc, extreme weather and so on. /. . ./ The very division between the physical and the social is itself a socio-historical product and one that appears to be dissolving (Urry, 2003, p. 17-18).

According to Franklin and Crang; [t]ourism is entirely populated by hybrids, and future investigations in tourism will need to enumerate and analyse their potencies (Franklin & Crang, 2001, p. 15). In this account, tourism literally is a hybrid population of phenomena that slips through the net of clear-cut categorizations of the social, and even more so when interrelations between them are taken into consideration. It is then not easy to distinguish what is social and what is material when it comes to a tourism that involves: hiking shoes, hotel beds, capitalism, destination images, discursive practices, whales, money, motivations, community development, exchange values, dancing, cameras, desires, cars, animals, homes, waiting, welfare policies, taxes, tour operators, apples, guides, day dreaming, fuel emissions, smiling, electricity, sunbathing, governance, spreadsheets, maps, expectations, promotion brochures, weather, aircraft, food, neo-liberalism, and what not else. The implication for tourism theory is that since such mixtures are

162

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

ambiguously neither material nor social they cannot be mapped onto the reference plane of a puried social without severe reduction or distortion. This also suggests that tourism only occurs partly in society and that tourists are at best only partially social. Tourists are always dependent on non-humans (here meant to signify all that is other than human, be it weather, a credit card, or a polar bear) and their material agencies, if for no other reason than simply being able to travel and stay away from their normal home environment for a variety of purposes (Beaver, 2005, p. 380). One could argue further that tourism is not only entirely populated by hybrids, but is itself a hybrid, a mixture of various phenomena, but one which has been transformed into a delimited phenomenon after labours of ordering and purication. What is referred to as tourism is then an abstraction from the concrete population of whatever is provided on the Earth, and whose belonging to the domain of tourism is constructed a posteriori. Actor-network Theory and Tourism The notion of hybrids, or rather mixtures of various ingredients, together with the importance of material things for the social, puts the role of non-humans and material agency in the constitution of the social centre stage, in opposition to an understanding of tourism as a social sui generis. The best known approach in social science in which hybrids, including non-humans and relational material agencies, have been incorporated is actor-network theory. Those who have tried to translate it into tourism studies (Franklin, 2004; Jo hannesson, 2005; Paget, Dimanche, & Mounet, 2010; Ren, Pritchard, & Morgan, 2010; Rodger, Moore, & Newsome, 2009; Van der Duim, 2007) have indeed emphasised this heterogeneous character of tourism as being held together by active sets of relations in which the human and the non-human continuously exchange properties (Van der Duim, 2007, p. 964). Without exchange of properties, through the associations and the performative orderings of humans and non-humans, there would simply be no tourism according to this formulation. In an attempt to develop a kind of analytical equivalent of actor-networks in tourism theory, Van der Duim has proposed the concept of tourismscapes that are materially heterogeneous and consist of relations between people and things dispersed in time-specic patterns (Van der Duim, 2007, p. 967). These tourismscapes are, like actor-networks, not to be understood as reied entities, but as topologically complex relational processes of ordering that may eventually become stabilized, or black-boxed, as tourists and tourism. According to Van der Duim, tourismscapes also involve the enactment of space so that they are connecting, within and across different societies and regions, transport-systems, accommodation and facilities, resources, environments, technologies, and people and organizations (Van der Duim, 2007, p. 967). In this account, informed and framed by ANT, tourism becomes a relational performative achievement made

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

163

possible by the association and ordering of humans and non-humans. This tourismscaping thus involves various material agencies which, again, mean that tourism can emerge as pure social phenomena only after specic forms of tourism actor-networking or ordering. We have no difculties in subscribing to the view that actor-network theory has much to offer tourism studies and tourism theory. Not the least for taking non-humans and material agency on board and for providing a methodology by which the performative ordering of tourisms and tourists can be studied. But since our task here is to re-cognise the Earth in tourism theory, it becomes important to avoid the possibility of understanding tourismscapes as self-contained enclosed topologically complex beings that produce their own spaces by connecting and disconnecting heterogeneous elements. As Clark argues:

. . . there are other situations in which the inference of relations of equivalence or co-production among all actors present seems to woefully underestimate the extremity of an extra-human materiality (Clark, 2010, p. 40).

For our purpose, we therefore need to situate tourismscapes in relation to that extra-human materiality that is the Earth. In our conceptualization this means that the Earth becomes a plane of reference and provider of consistency for all actor-networking (Gren, 2002, p. 268 269), and that tourismscaping becomes a particular form of re/ de-territorialisation of the Earth that has tourism as (e)scape. Back to Earth A theoretical re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory requires an ontological commitment to the Earth. As outlined in the previous section, the understanding of tourism as foremost an ordering of heterogeneous materials renders traditional social science theorising rather problematic, if not obsolete. Moreover, a self-referential understanding of the social leads to the mapping of only that which has already been assembled and puried as social and leaves out generating non-social ingredients that may have been involved in its becoming such. When the object of study is a mixture of various phenomena and their connections a socio-graphy which consists of mapping the social onto the reference plane of a separate social may be:

Completely useless for tracing what should be common to the other types of domains. In other words social might throw light on the social, but thats all, when what we now need is a type of connection that sheds light on all of the other types of connections as well (Latour, 2007, p. 4).

So, what type of connection could be used in order to shed light on all of the other types of connections as well? What could be useful for tracing what should be common to the other types of domains, be they not only social but also spatial, material, technological, political, cultural, economic, environmental, touristic, or some other? As expected our answer is of course the Earth! Wary of reications, and

164

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

steering clear of the peculiar modus operandi when the social could explain the social (Latour, 2005, p. 3), we suggest here only one possibility of theorisation, that is, the Earth as a primary plane of reference on which all types of elements and relations must continually (dis)connect. With the use of brackets around antonymous prexes, such as (dis)connect, (w)hole, (in)consistent and (e)scape, we want to convey a processural understanding of the earth [a]s not one element among others but rather brings together all the elements within a single embrace (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 85), whilst not arresting these. Thus conceptualised the Earth is clearly not one element among others, nor a reied it, but instead something on which the whole process of production is inscribed [. . .] a mega machine that codes the ows of production (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983, p. 141142). Continually all-embracing and omni-present, the Earth is consistent with all, yet simultaneously referable to itself as the Earth in particular. In the context of tourism theory such an ontological apprehension means that the Earth becomes that plane on which all tourism congurations and ows must meet the demands for (in)consistency. Although these, as well as tourismscapes, are all ultimately of the Earth, in practice the Earth will always already have been part and parcel of these. The Earth will always be provisional and in suspension, part and not yet part, as; the shortcoming of the ground is to remain relative to what it grounds, to borrow the characteristics of what it grounds, and to be proved by these (Deleuze, 1994, p. 110111). To provide the researcher with a tool to deal with this shortcoming we now need to introduce the concept territorialisation. In a geo-philosophical understanding territorialisation refers to bringing together, whilst simultaneously apart, elements from and to the Earth. Thus territorialisation actually involves two interrelated processes; deterritorialisation and re-territorialisation. In the words of Deleuze and Guattari:

Movements of deterritorialization are inseparable from territories that open onto an elsewhere; and the process of reterritorialization is inseparable from the earth, which restores territories. Territory and earth are two components with two zones of indiscernibility deterritorialization (from territory to earth) and reterritorialization (from earth to territory). We cannot say which came rst (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 8586).

De/re-territorialisation thus refers to movements and transformations of the Earth to various territories (in relation to sensi/able spaces, see; Huijbens & Jo nsson, 2007) and vice versa. These processes of territorialisation thus inhabit the conjunctive between Earth and territory without restricting one by the other or excluding the other from the one (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983, p. 76). Any human practice that, like tourism, requires that humans and non-humans meet and interact somewhere on the Earth involves territorialisation. Concomitantly those processes which reduce the need for such co-presence would then be considered de-territorialising. In turn, these can

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

165

eventually lead to re-territorialisations elsewhere. In other words, processes of territorialisation, which most often involve technologies and enactments together with non-humans, are those that bring forth, dene, or sharpen boundaries of territories on and of the Earth, or that produce, sustain or increase the internal homogeneity of a territory. But territorialisation cannot be without its counterpart. It always already follows that de-territorialisation refers to processes that destabilize or decrease internal heterogeneity, eventually leading to destruction of an existing order, or to a re-territorialisation of a new order. As DeLanda suggests, de/re-territorialisation is a concept that must be rst of all understood literally (DeLanda, 2006, p. 13). This means, for example, that one may conceptualise all material entities on the Earth, such as mobile phones, volcanoes, houses, pancakes, buses, gravel and living organisms, as territorialised matter, or slowed down matter-movements. This, however, does not exclude expressive components like language and coding (Deleuze & Guattari, 1988), indeed one of the most important human aspects of territorialisation is that: thinking takes place in the relationship of territory and the earth (Deleuze & Guattari, 1994, p. 85). Of further importance to note is that territory as a spatially demarcated area of the surface of the Earth, for example a tourist destination, is but one possible form of territorialisation. Other forms are more topologically complex and mobile, as illustrated by the networking and channelling of tourism between destinations. The Earth geo-philosophically apprehended is composed of a myriad of dynamic matter-movements that the eeting human existence cannot grasp nor express in its innity and dynamism. In terms of representation in tourism studies, this means that processes of de/reterritorialisation, how orderings take place through disordering, are much more important to pay attention to, in tourism as well as elsewhere. The ontological apprehension of the Earth always remains in the conjunctive as the perpetual ordering is in-exhaustive, as the Earth is, and even more so (see Clark, 2005). CONCLUSION The aim of this paper has been to contribute to a conceptual re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory by probing some theoretical obstacles and possibilities. One obstacle that we have experienced ourselves, and which was pointed out by one of the reviewers, is the difculties in presenting the Earth as important in and for conceptual re-cognition in tourism theory, and simultaneously avoid reifying it as an object. Thinking about the Earth as an object, as a ready-made playground for human activities, as an external other, in short as an it, is of course what we wish to avoid since it mirrors the idea in social science of a separate reference plane of the social. What we have tried to demonstrate is that tourism studies and tourism theory have been lodged within a particular kind of social theorising which reects a broader conceptual trajectory. From its beginning

166

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

the train of modern social science and social theory have been bound for the concept of the social, bypassing other possible stops such as the Earth. As evident in tourism studies, even concepts like space, place and landscape are predominantly theorised according to social constructivism. Consequently, in tourism theory the phenomena of tourism and tourists are conceived of as occurring in society where tourists endure as social subjects in a social world, and not as earthlings on and of the Earth who participate in that particular form of de/re-territorialisation that tourism is. Yet, although the social veils the Earth in tourism theory, this veil is penetrated through material things, hybrids, mixtures of heterogeneous materials, non-humans and their material agencies, and their co-relational effects as explored in particular through actor-network theory (for more on the material turn see for example; Whatmore, 2002 and Hinchliffe, 2007). We have, however, also taken a step further than simply showing how the material may peek through the social and suggested an ontological entry point for the Earth and its innite matter-movements. By drawing on geo-philosophy we have provided one particular possible example of how the Earth can be theorised in tourism theory: as a primary reference plane of and for those de/re-territorialisations that involve tourisms and tourists. In the construction of tourism theory and the development of tourism studies as a eld of social science, the reference plane of a separate social has been a necessary and, undoubtedly, a productive step. One may well argue too that it has also contributed to the success of tourism on the ground, and that it continues to do so. More generally, there is little doubt that the social thus brought forth has signicantly contributed to the production of the modern socius of the human species and the constitution of their modern settlement: society with nature as the other. But what happens if we were to conceive ourselves as no longer primarily living in society, or a social world, but on the Earth in various collectives of humans and non-humans? As Latour puts it:

When we believed we were modern, we could content ourselves with the assemblies of society and nature. But today we have to restudy what we are made of and extend the repertoire of ties and the number of associations way beyond the repertoire proposed by social explanations (Latour, 2005, p. 248).

The most important conclusion that we draw is that a re-cognition of the Earth in tourism theory, based on our probing, will need to conceptualise the reference plane of the social, along with other possible ones, as secondary relative to the reference plane of the Earth. This means also that the reference plane of the social is to be theorised as being itself but one example of the re/de-territorialisation of the Earth. Furthermore, this suggests that the social, together with other possible reference planes, like the spatial, the cultural, the economic, the political, tourism, nature and the material, should not be distinguished as an explanatory domain of its own. Instead, the social would be conceived of as both product and producer of processes of de/re-territorialisation on and of the Earth.

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

167

As important as the Earth may be, a return back to an Earth as a foundation or somehow reied is certainly not an option for social science, nor for tourism studies. The question; if the Earth had a philosophy, what would it be? (Lambert in Buchanan & Lambert, 2005, p. 220) may be important to pose, but answers will always be provisional and in suspension. Nevertheless, we do believe that an explicit apprehension of the Earth as a plane of reference (or (in)consistency), itself composed of continuous matter movements and in a state of continuous de/re-territorialisation, may at least open up a virtual potential for actualising a different Earth trajectory within tourism theory. In addition, even though we do not mind making however small a contribution to remedy what has been referred to as the poverty of tourism theory (Franklin & Crang, 2001, p. 6), our project should also be literally Earthly situated. As topics such as climate change, environmental crisis, sustainable development, low-carbon society, and global warming grow in public awareness, the more issues about inhabiting the Earth are brought to the fore (Bramwell & Lane, 2008; Farrell & Twining-Ward, 2004; Go ssling & Hall, 2006; Lovelock, 2006). In terms of a common planetary fate and that of all Gods creations, we may have reached a point where we have been taking the whole Creation on our shoulder and have become now literally and not metaphorically in our action coextensive to the Earth (Latour, 2008, p. 4). As The Brundtland commission wrote two decades ago; The Earth is one but the world is not (The Brundtland Commission, 1987, p.54). As Tribe and Xiao have recently asked, could it be that social science is no longer a useful academic lens or grouping for tourism (Tribe & Xiao, 2011, p. 23)? If the eld of tourism studies has been dominated by policy led and industry sponsored work so the analysis tends to internalize industry led priorities and perspective (Franklin & Crang, 2001, p. 5; Shaw & Williams, 2004, p. 275), then we have tried to open a small window in the house of tourism studies for Earth led priorities and perspective. In doing so we ought to be in good company, for what are tourism studies for, if not to attempt to understand and explain the touring movements of human and non-human earthlings on the Earth?

AcknowledgementsWe would like to thank the reviewers for helpful and constructive comments.

REFERENCES

Baldacchino, G. (2010). Re-placing materiality: A Western Anthropology of Sand. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 763778. Beaver, A. (2005). A dictionary of travel and tourism terminology. Wallingford: CABI Publishing. Bonta, M., & Protevi, J. (2004). Deleuze and geophilosophy: A guide and glossary. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

168

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2008). Editorial: Priorities in sustainable tourism research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 16(1), 14. Buchanan, I., & Lambert, G. (2005). Deleuze and space. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Clark, N. (2005). Ex-orbitant globality. Theory, Culture & Society, 22(5), 165185. Clark, N. (2010). Volatile worlds, vulnerable bodies. confronting abrupt climate change. Theory, Culture & Society, 27(23), 3153. Cohen, E. (2008). The changing faces of contemporary tourism. Society, 45, 330333. Coles, T., Hall, M. C., & Duval, D. T. (2006). Tourism and post-disciplinary enquiry. Current Issues in Tourism, 9(45), 293319. Davos Declaration (2007). Climate change and tourism responding to global challenges. Second International Conference on Climate Change and Tourism, Davos, Switzerland. Retrieved 6 September 2009, from <http://www.unwto.org/pdf/ pr071046.pdf>. DeLanda, M. (2006). A new philosophy of society: Assemblage theory and social complexity. London and New York: Continuum. Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. London: Continuum. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1988). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Athlone Press. Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy?. London and New York: Verso. Dennis, K., & Urry, J. (2009). After the car. Cambridge: Polity Press. Doel, M. (1999). Poststructuralist geographies: The diabolical art of spatial science. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Farrell, B. H., & Twining-Ward, L. (2004). Reconceptualizing tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(2), 274295. Franklin, A. (2003). Tourism: An introduction. London: SAGE Publications. Franklin, A. (2004). Tourism as an ordering: Towards a new ontology of tourism. Tourist Studies, 4(3), 277301. Franklin, A., & Crang, M. (2001). The Trouble with tourism and travel theory?. Tourist Studies, 1(1), 522. Giddens, A. (2009). The politics of climate change. Cambridge: Polity. Gren, M. (1994). Earth writing: Exploring representation and social geography in-between meaning/matter. University of Gothenburg: The Department of Human Geography. Gren, M. (2002). Plattjordingarnas a terkomst. In B. Lundberg, G. Gustafsson, & L. Andersson (Eds.), Arvegods och nyodlingarKulturgeogra i Karlstad vid millennieskiftet (pp. 261274). Karlstad: Avdelningen fo r geogra och turism, Karlstad University Studies. Gren, M. (2009). Gunnar olsson. In R. Kitchin & N. Thrift (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of human geography (pp. 2729). Amsterdam: Elsevier. Gren, M. (in press). Gunnar Olsson and humans as geo-graphical beings. In C. Abrahamsson, M. Gren (Eds.), GO: on the geographies of Gunnar Olsson. Hampshire: Ashgate. Gren, M., & Tesfahuney, M. (2004). Georumsloso: ett minifesto. In K. Schough & L. Andersson (Eds.), Om geometodologierkartva rldar, va rldskartor och rumsliga kunskapspraktiker (pp. 4576). Karlstad: Karlstad University Studies. Go ssling, S., & Hall, M. C. (2006). Uncertainties in Predicting Tourist Flows under Scenarios of Climate Change. Climatic Change, 79(34), 419435. Hinchliffe, S. (2007). Geographies of nature: Societies, environments, ecologies. London: SAGE. . P. (2007). Sensi/able spaces Space, art and the Huijbens, E. H., & Jo nsson, O environment. Proceedings of the SPARTEN conference. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Press. Holden, A. (2005). Tourism studies and the social sciences. London & New York: Routledge. Holden, A. (2008). Environment and tourism. London: Routledge.

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

169

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2007). Summary for policymakers. Retrieved September 6, 2009, from <http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg1/ar4-wg1-spm.pdf>. Jo hannesson, G. T. (2005). Tourism translations: actor-network theory and tourism research. Tourist Studies, 5(2), 133150. Johnston, R. J., Gregory, D., Pratt, G., & Watts, M. (Eds.). (2000). The dictionary of human geography. Oxford: Blackwell. Knudsen, D. C., Metro-Roland, M. M., Soper, A. K., & Greer, C. E. (2008). Landscape, tourism, and meaning. Aldershot: Ashgate. Larsen, J., Urry, J., & Axhausen, K. W. (2006). Networks and tourism: mobile social life. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(1), 244262. Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Latour, B. (2007). A plea for earthly sciences. Retrieved March 16, 2009, from <http:// www.bruno-latour.fr/articles/article/102-BSA-GB.pdf>. Latour, B. (2008). Its the development, stupid! or How to Modernize Modernization. Retrieved March 16, 2009, from <http://www.bruno-latour.fr/articles/article/ 107-NORDHAUS&SHELLENBERGER.pdf>. Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell. Lew, A. A. (2001). Literature review: dening a geography of tourism. Tourism geographies, 3(1), 105114. Lew, A. A. (2003). Editorial: tourism in places and places in tourism. Tourism Geographies, 5(2), 121. Lovelock, J. (2006). The revenge of Gaia. Why the earth is ghting back and how we can still save humanity. London: Allen Lane. Luhmann, N. (1995). Social systems. Stanford: Stanford University Press. MacCannell, D. (1999/1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Berkeley: University of California Press. Netz, R. (2004). Barbed wire an ecology of modernity. Middletown, CT: Weslyan University Press. Olsson, G. (2007). Abysmal a critique of cartographic reason. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Page, S. J., & Connell, J. (2006). Tourism A modern synthesis. London: Thomson. Paget, E., Dimanche, F., & Mounet, J.-P. (2010). A tourism innovation case: an actor-network approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(3), 828847. Pons, P. O. (2003). Being-on-holiday. Tourist dwelling, body and place. Tourist Studies, 3(1), 4766. Ren, C., Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (2010). Constructing tourism research: a critical enquiry. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(4), 885904. Rodger, K., Moore, S., & Newsome, D. (2009). Wildlife tourism, science and actor network theory. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(4), 645666. Saarinen, J. (2006). Traditions of sustainability in tourism studies. Annals of Tourism Research, 33(4), 11211140. Scott, D. (2011). Why sustainable tourism must address climate change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(1), 1734. Sharpley, R. (1994). Tourism, tourists and society. Huntingdon: Elm Publications. Shaw, G., & Williams, A. (2004). Tourism and tourism spaces. London: SAGE. Sheller, M., & Urry, J. (Eds.). (2004). Tourism mobilities: Places to play, places in play. London: Routledge. Simmel, G. (1971). On individuality and social forms. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press. Stergiou, D., Airey, D., & Riley, M. (2008). Making sense of tourism teaching. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(3), 631649. The Brundtland Commission. (1987). Our common future. In S. Wheeler & T. Beatly (Eds.), The sustainable urban development reader (pp. 5457). Oxon: Routledge. Tribe, J., & Xiao, H. (2011). Editorial: developments in tourism social science. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(1), 726. Urry, J. (2002). The tourist gaze. London: SAGE Publications. Urry, J. (2003). Global complexity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

170

M. Gren, E.H. Huijbens / Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2012) 155170

Van der Duim, R. (2007). Tourismscapes: an actor-network perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(4), 961976. Weaver, D. (2011). Can sustainable tourism survive climate change?. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(1), 515. Whatmore, S. (2002). Hybrid geographies: natures, cultures, spaces. London: SAGE Publications. Submitted 22 October 2009. Resubmitted 9 June 2010. Resubmitted 20 January 2011. Resubmitted 31 January 2011. Final version 2 February 2011. Accepted 27 May 2011. Refereed anonymously. Coordinating Editor: Irena Ateljevic

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Jackson V AEGLive - May 10 Transcripts, of Karen Faye-Michael Jackson - Make-up/HairДокумент65 страницJackson V AEGLive - May 10 Transcripts, of Karen Faye-Michael Jackson - Make-up/HairTeamMichael100% (2)

- Lieh TzuДокумент203 страницыLieh TzuBrent Cullen100% (2)

- Dwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFДокумент35 страницDwnload Full Principles of Economics 7th Edition Frank Solutions Manual PDFmirthafoucault100% (8)

- Miniature Daisy: Crochet Pattern & InstructionsДокумент8 страницMiniature Daisy: Crochet Pattern & Instructionscaitlyn g100% (1)

- 15 Day Detox ChallengeДокумент84 страницы15 Day Detox ChallengeDanii Supergirl Bailey100% (4)

- Micro EvolutionДокумент9 страницMicro EvolutionBryan TanОценок пока нет

- Mosfet Irfz44Документ8 страницMosfet Irfz44huynhsang1979Оценок пока нет

- EPAS 11 - Q1 - W1 - Mod1Документ45 страницEPAS 11 - Q1 - W1 - Mod1Alberto A. FugenОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Screenwriting UEAДокумент12 страницIntroduction To Screenwriting UEAMartín SalasОценок пока нет

- Skills Checklist - Gastrostomy Tube FeedingДокумент2 страницыSkills Checklist - Gastrostomy Tube Feedingpunam todkar100% (1)

- 40 People vs. Rafanan, Jr.Документ10 страниц40 People vs. Rafanan, Jr.Simeon TutaanОценок пока нет

- Microsmart GEODTU Eng 7Документ335 страницMicrosmart GEODTU Eng 7Jim JonesjrОценок пока нет

- Activity On Noli Me TangereДокумент5 страницActivity On Noli Me TangereKKKОценок пока нет

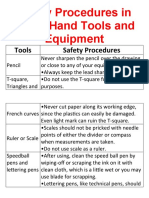

- Safety Procedures in Using Hand Tools and EquipmentДокумент12 страницSafety Procedures in Using Hand Tools and EquipmentJan IcejimenezОценок пока нет

- Chapter 13 (Automatic Transmission)Документ26 страницChapter 13 (Automatic Transmission)ZIBA KHADIBIОценок пока нет

- My Mother at 66Документ6 страницMy Mother at 66AnjanaОценок пока нет

- Friction: Ultiple Hoice UestionsДокумент5 страницFriction: Ultiple Hoice Uestionspk2varmaОценок пока нет

- Sample - SOFTWARE REQUIREMENT SPECIFICATIONДокумент20 страницSample - SOFTWARE REQUIREMENT SPECIFICATIONMandula AbeyrathnaОценок пока нет

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesДокумент1 страницаDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesJonathan CayatОценок пока нет

- Pg2022 ResultДокумент86 страницPg2022 ResultkapilОценок пока нет

- QSP 04bДокумент35 страницQSP 04bakrastogi94843Оценок пока нет

- An Evaluation of MGNREGA in SikkimДокумент7 страницAn Evaluation of MGNREGA in SikkimBittu SubbaОценок пока нет

- LM2576/LM2576HV Series Simple Switcher 3A Step-Down Voltage RegulatorДокумент21 страницаLM2576/LM2576HV Series Simple Switcher 3A Step-Down Voltage RegulatorcgmannerheimОценок пока нет

- Clockwork Dragon's Expanded ArmoryДокумент13 страницClockwork Dragon's Expanded Armoryabel chabanОценок пока нет

- DBMS Lab ManualДокумент57 страницDBMS Lab ManualNarendh SubramanianОценок пока нет

- Quarter 1 - Module 1Документ31 страницаQuarter 1 - Module 1Roger Santos Peña75% (4)

- Export Management EconomicsДокумент30 страницExport Management EconomicsYash SampatОценок пока нет

- Fire Protection in BuildingsДокумент2 страницыFire Protection in BuildingsJames Carl AriesОценок пока нет

- Micro Lab Midterm Study GuideДокумент15 страницMicro Lab Midterm Study GuideYvette Salomé NievesОценок пока нет

- Speech On Viewing SkillsДокумент1 страницаSpeech On Viewing SkillsMera Largosa ManlaweОценок пока нет