Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Psychoanalysis PDF

Загружено:

scrappyvИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Psychoanalysis PDF

Загружено:

scrappyvАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

*n

a system of

*Y,'

( nr)

,'4-

rvute?

4 P"t

.7'J"b4 ,o^^.'( tu*$.

course on evolution taught by Carl.Gla=its, ald a oourse on the physiologr ofvOice and speech

p ,

)xU

'

4Y

/'

PSYCHOANALYSIS

CuaprBn 16

PSYCHOANALYSIS

The ego is not master in ifi own house. -Sigmund Freud (1917n955)

would have been his preference

taught by Ernst Briicke. In his third year, Freud was the recipient of a grant thakpal{ fA{Jw! brief rrips ro Trisre, where he ffiaged in iesearch in marine biology. Freud's interests centered mainly on research in anatomy and physiology. Indeed, it

to

have

worked as a researcher in Ernst Briicke's phy-

Like behaviorism, psychoanalysis is more than psychologSr. It is an intellectual movement that has had a deep and pervasive influence in many fields, including literature, philosophy, religion, and history. The conrinuing influence of psychoanalysis in a host of intellectual and professional arenas is evidenced by the number of papers on the subject at sclentific and professional conventions. Meetings of historians, artists, philosophers, psychiatrists, and psychologists as well as conventions for those interested in the study of religion or literature are almost certain to include

proximately 5,000 people. His father, Jakob Freud, was a wool merchant who had two sons by a previous marriage. Sigmund was the fint

siologr laboratory, but tlismal prospects for advancment aswell as personal financial exigencies forced lriininto a medical cafeer. He served as a resident in the Vienna General Hospital from July 31, 1882,.to August of

During this period, he gained experience in surgery, internal medicine, dermatologr, and ophthalmologr, but he had little interest in any of these fields. His interests picked up, however, when he worked in Theodore Meynert's psychiatric clinic and in Franz Schol's Department of Nervous Diseases. In September of.1885, Freud was appointed privatdozent (a lecturer paid only by student fees) in neuropatholory. Subsequently, he spent five months in Jean-Maftin Charcot's clinic in Paris, where he developed an interest in hysteria and hypnosis. Freud's experiences in Paris were pivotal because the emphasis there wfls on the psychological nature of emotional problems, whereas the emphasis in Vienna had been on physical in1885.

Sigtrwnd Freud

numerou$ papefs that attack or defend psychoanalysis or present topics in terms of psychoanalytic perspectives. Psychoanatysis, like behaviorism;;fus had an unusual capacity to provoke loyqlty and hatred; neither is there :agreement about the continuing impact of psychoana$sis on psychology. We can find those who believe that the influence of this school is in decline and those who argue that psychoanalysis is alive and well. In terms of the sheer numbers of professional organizalions and journals, lhg weight of the evidence is with those who see psychoanalpis as alive and well. We will now turn to a consideration of the classic psychoanalytic system. We begin with a sketch of the biography of Sigmund Freud and then turn to a consideration of his

system ()f thought.

of the eight children of Jakob and Amalie Nathansohn. In 1.860, Jakob and Amalie settled in Vienna, a city that was to be Freud's home for the next 78 years. Though Freud was raised and educated in Vienna, it was not a location that could inspire his loyalty. Prevailing antisemitism undermined the quality of dayto-day life and severely narrowed the range of vocational choices for Jews. In his standard biography of Freud, Jones (1953) relayed the story of a ruffian who knocked Jakob Freud's new hat into a puddle of mud with the demand, "Jew get off the pavement" (p.22).

Jews were repeatedly the victims of demeaning

electricity through the skin and muscles of the head on the as$umption that such currents would improve circulation. Deficiencies in circulation had long been assumed to be implicated in mental disorders. [.ater, Freud used hypnotic suggestion and still iater the calhartic method. The technique of free association was developed parrly because of Freud's disillusionmeni with other therapeutic methods.

Freud grabually inroduced ihanges in the method on lhe basis of his clinical experience

and commenB from his patients. The work for which Freud is most remembered is his major book, The Interpretation of

acts and hostile humor. Understandably, such a climate had a profound effect on the thought

and character of Sigmund Freud (e,g., Bakan, 1958; Miller, l98l; Roith, 1987).

see

Freud, always a precocious student, gradu-

terpretations. Following his work in paris, Freud returned to Vienna and set up a private practice on April 25, 1886. In that sams year, after a long engagement, he married Martha

BernaSn.

Sigmund Freud was born on May 6, 1856,

in Freitrerg, Moravia, a small town of

376

ap-

ated from high school sumrna cum laude at age 17. He loved literature, history, science, and language. His facility with languages was demonstrated by his knowledge of Latin, Greek, French, English, Italian, Spanish, and Hebrew. In 1873, Freud matriculate-d in the University of Vienna, where he pursued a degree in rnedicine. Like William James, however, his interests ranged over the entire curricuhrm. He attencled courses in philosophy and psychology taught by Franz Brentano, a

The system of treatment that, among other lhings, gave Freud such a prominent ptace in history did not develop suddenly. Indeed, the tetmpslchoanafsr.r did not appear until 1g96, fully 10 years after Freud had established his practic (Jones, 1953, p. 244). ln the earliest phases of his. practice, Freud used phpical methods such as electrotherapy (which is not to be confused with electroiirock). Electrotherapy consisted of passing small currnts of

Dreants, published in 1900. In this book, Freud advanced his well-known position that dreams represent wish fulfillments in disguise. The book, now regarded as a classic in psycholory, did not bring inslantaneous fame to ils author. Indeed, initial reaction was hostile, especially in some Viennese circles. Slowly, however, the book attracted attention and

within l0 years after its publication, Freud,s

fame was assured.

Freud's bibliography foltowing The Interpretafion of Dreans reveals an impressive output of maior books, shorter papefs, and case histories that elaborate and extend his sptem of psychological rhought. So prolific were his writings that the collected works are now con-

...

378

cl{APrERl6

jaw, was forced from his home by the Nazi invqsio4. He died in l,ondon on September 23, TIB9.

SOME MAJOR CHARACTERISTICS OF FISSUDS TIFOUGHT cesses. In his open letter to Einstein on the subject ofwar, Freud (193211964a, p. 204) {atsisted thst human beings have no grounds {or excluding lhemselves from the animal kingdom. Aceording to Jones (1953), Freud subscribed ro the evolutionary position that "no spirils, essences, or entelechies, no su;terior plans or ultimate purposes are at wor*. The stages

PSYCLIOANALYS$

tained in 23 volumes with an additional volume devoied to indexes and bibliographies (see Strachey, 1953-1974). The entiro fiorpus estsblished Freud as cnp of t&e great psychologists and a pioneer in aspects of the discipline that were ignored in other sptenm of

psychological thought. Freud's biographers paint the picture of a man whose personality was complex. On the one hand, he muld appear shy almost to the

that must be successfully negotiated if the individ$al is later to enjoy psychological

health and well-being. Emphasls on Motlvntlon

point of lacking confldence, but the

shyness

Though Freud's system of psychdogy evolved over time, there are several major philosophical assumptions that consistently guided his work We review here six characteristics of his

physical energies alone cause effectssomehow" (p. 42).Freud believed that there were distinct advantages in a rhors$Sfup&lg naturalistic approach to the study of human

beings.

was often only an apparance. Freud also had

thinking and then turn to a consideration of

some of the details of his sptematic position.

brief periods ofdepression, but he could also

be joyful, enthusiastic, or even jubilant. His creativity was by no means consistent. There

wore times of inhibition,

or even dullness,

Determinlsm

Role of Unconscious Influences

when he seemed quite incapable of being productive. But such times were followed by bursts of creative activity and produclivity.

Unlike William James, Freud devoted no essay explicitly to the free will/determinism issue. Nevertheless, he repeatedly expressed his

One of the unique features of Freud's s)6tem-

Freud had a strong devotion to his family arid a considerable capacity for commitment. Although he worked unusually long hours, he nevertheless found time to be with Martha and their five children. His tasts in music were severely truncated, but he had an enormous capacity to enjoy art, especially sculpture. His major indulgence was a cotlection of antiquities (sculptures of ancient figures) that

preference for theoretical determinism and for

a methodology

that assumes natural causes for

atic approach to psychologr is encountered in his belief in the importance <lf unconscious processes. He strongly believed that he could demonstrate that rational processes may ac!ually serve unconscious motives. He understood that his position struck a blow at human narcissism and that it challenged our cherished

The major sl,stems of psychologt are olten as. sociated with preferential areas of study. For example, structuralism placed lts slronge8l emphasis on the study of lhe senses, whercas behaviorism emphaslzed learnlng. The content area that is prlvileged tn Freudlan psycholog is motivation. Freud repeatedly refen to the oentrality of pleasure in human life and to specific determinants of its expression. Furthermore, hls discussions of hiS patienls and their problems are inevitably couched in the language of motivation. Though Freud did not deny the crucial roles of learning, perception, and social influence in human life, clearly his emphasis was on motivation. Applied Psychologr

all mental events. Gay (1988) stated "It is a crucial point in Freud's theory that lhere are no accidenls in the universe of the mind" (p.

119).

In his book entitled FreuQ Biologkt of

belief

the Mind, Sulloway (1979) noted that "Freud's entire life's work in science was characterized

by an abiding faith in the notion that all vital

afforded large measures

of

intellegtual and

aesthetic pleasure. Freud's last days were spent

in exile in

London, England. Austria had been invaded by the Nazis in 1938 and Freud, at first defiant, was finally persuaded by his friends to leave Vienna. His affiliation with B'nai B'rith, as well as his theories, made him a prime target for Nazi hostilitios. Indeed, Gay (1988, p. 592) called attention to the fact that Freud's books, along with those of other intellectuals, were burned by the Nazis in numerous public

squares L933. Freud's theories have never been popular in totalitarian regimes, possibly because of the psychoanalytic emphasis on the uncon$cious determinants of cognitive procsses. In any case, Freud, already a sick man and dying from cancer of the

phenomena, including psychical ones, are rigidly and lawfully deterrnined by the principle of cause and effect" (p. 9q). Other scholars (e.g., Brown, 19i4, p. 3; Jones, 1953' p' 304; Wisdom, 1943) have also ernphasized Freud's strong commitment to determinism. As we will see later, however, there are some possible meanings of freedom that surface in Freud's system of thought.

'Belief in the Continuity of the Animal Kingdom

in human rationality. According to Freud (1917i1955), "the ego is not master in its owtr house" (p. 1a3). Nevertheless, Freud believed that human beings need not remain in bondage to unconscious influences. Indeed, as we will see later, the goal of psychoanalysis, in Freud's words, is to return back to the ego "its mastery over lost provinces of . , . mental life" (Freud, 19381I964b,p. I73).

Developmental Emphasis

A final emphasis in the psychologrof Sigmund Freud is on application. Freiid's theoretical interests ran deep, but he was equally interested

in dweloping a psychologr that could

speak

effectively to the daily problems of life. Thus, a great deal of his intellectual energr was de' voted to the problems of effective intervention and treatment. Indeed, the very lerm psychoanalysis seems to refer simultaneously both to a system of psychology and to a treatment

technique. The two ale sepatated only with

difliculty.

FREUD'S SYSTENI

A hallmark of classic psychoanalytic theory is the importance it gives to development and

growth. Frgud was deeply sensitized

to

the

on May IO,

In his autobiographical

study, Freud (1924l

1959a) noted that Darwin's theory had a powerful influence on his thinking because it sug-

gested that our understanding of the world may grow through knowledge of natural pro'

idea that needs and abilities vary as a function of age. He also believed that there are critical periods, or periods-of miliimal sensitivity to certain qualities of stimulation. According to Freud's theory, early evnts in life are consequential to later adjustment. Flrthermore, he believed there are identifiable developmental

Psychoanalytic theory and practice changed

and developed, sometimes rather dramatically, over the 43 years of Freud's professional career. In fact, one of his initial ambitions was to

advancr a psycholory thoroughly anchored in neurologr and physiology-a psychology that would be worthy as a natural science. Freud's

CHAPTER 16

PSYCHOANALYSIS 38I work in greater or lesser degree agalnst the

pleasure that we so highly prize. happiness and independence from'the world, is the method of intoxication. Freud was not, however, impressed with the mental eco_ nomics of artificial intoxications because they represent an essential withdrawal ftom reality and require energ/ that could have been put to better use. Freud also included religion as one of the many defenses we erect ds a means of coping with the world. He compared religion to intoxication arguing thAt, in both cases, the.individual escapes from reality. Religion, he believed, places us in a state of mental infantilism that depreciates the value of this world and at the same time promotes the illusion of a better world to come. Freud's major critique of religion is contained in his well-known book The Future of an lllusion (Freud, l9Z7 ll96lc). Other defenses outlined by Freud included loving and being loved, enjoyment ofworks of

sfforls along these lines resulted in a paper entitld "Project for a Scientific Psychology." He quickly realized that it was premature to rtfffiipt to establirh rigorous connetions belwen the world of physiolory and the niorld of experience, so he abandoned the project. lficre were many other times that he followed

ialse leads

l'he Structurc of Personality

Freud conceptualized the struclure of human personality it terms of three interrelated systems that he called the id, ego, and wpuego (meaning, respectivly, the it, I, and over-I). The three s],xtems are in more or less continuous conflict-a conflict with which all hurngn beings must successfully mpe if they are to adapt to the world. The psychological adjustment of the individual depends on the maintenance of a reasonable bahnae among the

three systems. Indeed, severe oonsequence$ re-

snd had to backtrack and start over

rgain. T[us, the development of psychoanalyiis was not marked by a smooth linear pro3ression of ideas. In what follows, we begin

rith some of Freird's most mature thought.

Such thought, advanced during the later years

The lirst source of suffering is our own body, which is the material mediun for pleasure and pain. The body, doomed to progressive deterioration, sends a relentless suosossion of signals or warnings of its ftailty and inevitable demise. The second source of suffering, the'outer world, rages against us with unrelenting insults. Even the best of niches is beset with natural disasters and with bacterial and viral invasions that are a constant threat to life. Finally, and by far tho greatest source of suffering, is from other people. Freud was deeply tuned to the social sources ofpain and unhappiness-war, rape, theft, assault, prejudice, child and spouse abr;se, daily insensitivities and hostilities, dishonesty, authoritarian structures and attitudes*these are but a few of

rf his life, provides the broadest possible picturq of his approach to psychology. We then work back to hls earlier ideas to fill in some of

thc detalts

sult

if

any

of the three s)rslems are

unduly

of his theory.

Llfe's Mqlor Goal and Its Inevltable I'rustrqllon

countless possible examples

Discontents,

of this

third

In his book Civilization and lts

Freud (1930/1951a) stressed his

beliefthat the

pleasure principle dominates psychological prooesses. From the very beginning of life we ;eek pleasure and we seek to avoid pain. He rctd that pleasure results from the. satisfac-

tion of needs, but while we seek pleasure

lhrough the satisfaction of needs, we find that lhe wqrld is not very cooperative with our ef-

iorts. Furthermore,

oui own constitution

Freud ob-

ruorks against sustained pleasure.

;erved that we know pleasure only thfough rontrast, but we have a constitutional incapacity to experience contra$t for sustained petiods. For example, ive may know . intense pleasure when wd submerge ourselves in a rath after shivering from the cold, but such )leasure is short lived. The constancy of the rath would itself become aversive if we remain n it too long. Freud (1930/l%la) reminded ris readers of Goethe's warning that "nothing

source of pain and suffering. In view of all of the sources of unhappiness, Freud (1930/ 1961a) wondered openly whether we are not justified in feeling that it was never intended that human beings should be happy. He went on to point out that some people find a modicum of happiness in the simple fact that they have temporarily escaped unhappiness. After outlining the sources of suffering, Freud then tumed to the remedial actions that are open to human beings. Though these actions seek to pre$erve pleasure, they are all tempofary in their effects and are thus flawed. Nevertheless, some are more economical than others and some more admirable. Freud discussed attempls at unbridled satisfaction of needs and noted that this method sets us at odds with others and is therefore not tolerated by society. One of the great growth tasks confronting every child is the task of lparning to

delay gratification or to substitute onelkind of gratification for another. Another method is to wlthdraw from the world and thus savor whatever satisfaction can be found in self-im-

art, and the flight into mental illness. According to Freud, hard work and science are the most admirable defenses against the sources of suffering. Through hard work and science, there is great potential to make lasting contributions for the good of others, yet Freud pointed out that work is seldom valued by the masses ofpeople. Freud acknowledged that his enumeration

of the strategies for attaining happiness and the defenses against suffering were incomplete. He argued that we are fighting a losing battle and that the demands of the pleasure principle cannor be,fulfilled. He believed that the different alternatives we artempt must ultimately be judged in terms of a kind of complicated equation that is duly sensitive to short-term and long-term interests and to individual and social interests. The difficulties, complexities, and ambiguities involved in the intelligent pursuit of happiness confront every human being. Freudt views on the pleasure principle and its vicissitudes provide an importaRt backdrop for understanding his views on the structure of personality and the nature of the stresses that all human beings face.

weakened. The three systems offer differing strategies for coping with the problem of the pleasure principle (discussed in the previous section). So, Freud's views on the structure of the personality must be viewed in the oontext of his vieq/s on the meaning of life's purpose. It should be noted that Freud often spoke of the id, ego, and superego almost as if they were localizable entities, but he intended them to be viewed as hypothetical systems that describe major functional areas of the human personality.

Thc Id. The id is rhe most primitive and, developmentally, the first component of personality. It represents powerful biological needs that are necessary to the physical survival of

the individual. The needs that rhe id represents are oommon to all animal species and they seek expression in the most <lirect biologically efficient manner. The id is not constrained by customs, morality, values, conventions, or ethi6. On the contrary,

it is impul-

sive and reflexive as it seeks immediate gratitication for those needs that it represents. The

s harder to bear than a succession of fair lays" (p. 76). In addition to the constitutional

nnstrainls

on

happiness, Freud outlined

l

hree great $ources of suffering that inevitably

posetl isolalion. Still another method, highly prized becarrse it produces a small portion of

id, according to Freud, operates purely on the of the pleasure principle in its most unconstrained manifestations The id is fepresented direct$i in impulsive and reflexive activity, but it is also expressed in what Freud called the primary process. The so-called primary proces$ includes images or memories of objects that serve to satisfy needs.

basis

382

CHAPTTR16

PSYCHOANALYSTS

For example, if one dreams of a sexual encounter and the dream is rich in imagery, then such imagery may be an example of primary processes. Such processes present tlrcmselves without the embellishnnents cf polite oocial convenlions and norms. Freud believed that the id is true psychic realiry serving the pleasure principle. He employed the term libido to refer to psychic energies that are directed toward need gratification. The libido, or libidinal energy, is usually directed toward loved or desired objects in the world (object libido) but it may attach itself to the ego. When this happens, self-love, or narcissism, replaces object love.

The superego, like the id, is nof fationat instead of serving the goal of pleasure, it serves the goal of perfection. The superego is a kind deonselenel with an inhib{to*y $nnc{ior, but <r*"r'ard ebove this, it facilile,tss action toward

achievement of higher values embraced by so-

tion, a.patient was hypnotized and given

'

ciety. In terms of its demands on the ego, the superego is no more realistic than thc id; both

syrtems make impossible claims.

and hold

open t[e physician's umbrella lwhictr haO pur_ posefully been lett in the corner of the robm)

tered t&e patient's room, the patient would

suggestion that was to be carried out laier (i.e., after the patient had been awakened from'the trance). The suggestion was that the next time the physician and the physician's assisrants en_

it

The inevitable tensions among the id, the ego, and the superego were highly important to Freud. Indeed, he believed that the relationship among these s],stems had far-reaching

patients. All three systems serve important roles and each system must find legitimate and acceptable expression. The id represents an imporocrnsequsnoes

over the physician's head. pre_

for the health of his

dictably, when the phpician an<t the assisrants returned to the room, the patient greeted the company, opened the umbrella, and held it ovei the physician's head.

The Eg. The ego is the I or me of the personality-the center of organization and integra-

tion. While the id is closely connecled to the demands of tho pleasure principle, the ego must adapt to the demands of reality. The ego is thus caught between powerful force-s and, as such, it must servo as a kind of administrator or executive. It cannot ignore the demands of the id, but unlike the id, neilher can it ignore the demands of the world of social dnvention. Caught between such powerful forces, it learns

tant dimension of life and this biological dimension cannot be ignored. On the other hand, if we are to live with other people in civilization, there must be inhibition and restraint. If the id dominates the ego, antisocial

behavior results and society must then take action to isolate and correct such behavior. on the other hand, a superego that ils.,,too powerful may block the expression of basic biological needs. Freud believed that the,damning up of biological drives results in the varieties of

to appropriate, compromise, substilute, and delay. Through such techniques it serves to protect the individual and the social order by finding appropriate and acceptable channels for the demands of the id. The ego makes use of plans that Freud referred to as the secondary process. The secondary process assists the primary process of the id by devising strategies through which drives can be satisfied in a socially accptable manner. It goes without saying that the ego must bo strong and durable to withstand the severe and continuous conflict imposed by the contradictory demands of the id and society. This is not the complete story, however; the ego must cope with still another force: the superego.

TIw

emotional difficulties that are so common in civilized societies. We will return & ghi* topic later. According to Freud, the ego must have sufficient strength to deal with the complex and sometimes capricious demands of the external world while at the same time permitting the compromised expression of troth the id

and the superego.

Commenting on such demonstrations, _ ..I Freud, as quoted

by Jones (1953), noted,

posthypnotic sugge$tion, the physician would talk to the patient and ask why he or she had engaged in such behavior. The patient, typi_ cally embarrassed, offered a raiionalization. For e6gmple, the patient might claim that rhe weather forecast had called for rain and that it seemed a good idea to open the umbrella and inspect it to make sure it does not leak. The fact is, patients were unable to explain their behavior because they could not consciously recall what had taken place during the hyp notic tranc. The patient might even "*piii ence thc opening of the umbrella as a free act and even defend the act with a rationalization. But other observers knew there were unoonscious forces that had contributed to the act.

re_

After the patient carried out such

rellgious experience. Freud provided an inter_ esting case study to illustrate this last point. The case srudy, entitled .A Religious Experience" (Freud, I9Z7ll96ld) tells of a young medical doctor who wrote to Freud to sharl the story of his religious conversion. The young doctor knew that Freud was an atheist and it was his hope to mnvince Freud of the reality of God. The doctor's letter told of see_ ing the body of a dear old woman on a cart being taken to a dissecting room. He was sud_ Ogn-U oyerwhelmed by rhe apparenr inJustice of dearh and the tinrit Oisposition of the re_ mains.of the old woman. He told Freud that he decided then and rhere ro give up his belief in God. But later as he was reflecting on the matter, he reported that a voice ,tpole to my soul that 'I should consider tne ltep I was

lhe.rongue, and everyttay purposeful forg6tthg such as rhe forgetting ofa dental appoinimenl No conscious event was sacrosanct-nol even a

choanalytic thoughr. No longer mutO don_ scious processes be viewed as autonomous, nor could we be certain that we are aware of all that is in the mlnd. Freud viewed it as a mistake to oquate mental protrcsscs with con_ sciousntxs alone. To defenrl the powcrl.ul rolc of unconscious forccs ln hunran"llfe, hc drew from hypnotlc. phenomena, dreams, rllps of

major inlluence on the development of psy-

sibility that there could be powerful mental

c3ived the profoundest impression of the pos_

processes which neverthetess iemained hidden from the consciousness of man" (p. 23S). pa_ basis

rg rake'" (Freud,t9T7l t96td,p.169). Following rhat o{ent, the young docior was overcome with fear and remorse and was converted to a complete acceptance of the Bible

1b9."t

and the teachings ofJesus Christ. In relaying this experience, the young doctor beseeched Freud to abandon hiJ own atheistic beliefs. Freud senr a polite reply to the doctor's letter and then proceeded to ina_

Motivation and Unconscious Processes Orgel (1990) pointed out that 'fthe core idea of psychoanalysis begins with the assumption that in every human being there is an unconscious mind" (p. l). Some of Freud's early experiences with hypnosis in H. M. Bernheim's clinic in 1889 had particularly important effects on the development of this part of his theory. Specifically, in a typical demonstra-

Superep. The superego consisls of.inter-

such hypnotic phenomena provided graphic examples of.mental processes that are clearly not in conscious awareness but that ur" n"u"itheless powerful determinants of behavior. At the $ame time, conscious explanations of the behaviors in question were demonstrably in_ ade_quate-one might even say illusory

tients, in fact, did not seem to understand the of their behavior. The demonstrations of

lyze the religious experience. The analysis raised a particularly cogent question at ihe outset. Why had the young doctor been so outraged and why had he renounced God at

for dissection? The question is cogent Oecause doctors see far more horrible sfuhts than a

the sight of the old woman being carried away

nalized social norms, ideals, and standards to

which the individual has been conditioned.

Bernheim's work with hypnosis, which Freud described as astonishing, cleariy had a

corpse destined for autopsy.

tt mist

be a pe_

.fr4

CHAPTER

16 .i

i

PSYCHoANALYSIS 385

solved as the boy gradually or suddenly abandons his competitive stance and ldentifies with

the.,

fol a non-Freudian, that this particular event sllould initiate i renunciation of belief in God and a subsequent religious conversion. It would have been far more-reasona$e if belief in God had been challenged by the protracted suffering ofa youngpenon, ,the senseless death of a child, or the ,heart arculiarity, gven

father. Identifying with powet, even ag-

rest

of a young adult undergoing

routine

gressive power, is a well-known psychological phenomenon. According to Freud, the Oedipus conflict is not fully resolved in early years, hence it may recur at later times in life. Following Freud's line of argument, it is no

will that places us fully in

agendas.

creation. Our self-confidence and pride, how_ ever, received still another btow when Freud argued against our long_held and cherished belief that we are rational creatures with a free

charge

wide oppoitunity hire for arbitrary choice,, (Freud, l9l5/l917a, p.124). He saw no rea_ . son, for example, why one might not posit in_

stincts for such activities as play or aggression. Elatorating on the arbitrary nature of classifi_ (ation systems, Freud (p. ti4) expressed doubt that there is a decisive basis for the distinction and classification of instincts. He went on to note that psychoanalysis had focused largely on the sexual instincts. The second characteristic of an insrinct is what Freud called the lmpetus. He used this term to refer to the amount of energr that is associated with the activity in question. He also used lhe expression motor element to de_ fine term impettts. presumably, the impe_ the tus of the instinct grows as a ftrnction of ihe amount of time that has lapsed since the initi_ ating source of the instinct was first felt.

of our own

surgery. Doctors see tragedies far worse than that of the corpse of an old person being taken i to a dissecting

room.

But Freud reasoned that this particular

event was well suited to initiate the doctor's convenion because lhe event aroused unconscious associations and motives. Freud argued that the slght of the old woman had triggered assoclations of the doctor's mother. In this case, lhe cruel fate of the mother is the work of Ood the father. ln a cry of outrage, the doctor then rebelled against the source of the indlgnity and injustiee. He would no longer believe in God. But why, then, was the doctor so "tepresents ther who only hours before is renounced. The reason for the conversion, according to Freud, is found in an unconscious conflict that most human beings experience at an earlier stage in

accident that the young doctor.could not maintain his indignation at Cod. God, in the doctor's belief sptem, was too powerful, and the mere suggestion that he should consider the step he was about to take quickly led to fear followed by remorse for his rebellion

against God. Resolution is achieved through a

work entitled .,Instincts and Their

equivalent for the Germa

Though Freud emphasized the role of un_ in human life, his larger vi_ sion of human motivation was much-mor" complicated and multidimensional. We turn now to consider some of the additional dimen_ sions of his theory as set forth in an important

conscious forceb

tudes" (Freud, l9l5/195;:la). Unforrunarely,

Vicissi_

quickly converted? Conversion, in this case, surrender to the same God and fa-

their lives. Furthermore, it is a conflict that can be reexperienced symbolically at later

stages in

life.

Freud believed that the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rer is characteristic of conllicts that

young children experience. A child may build a

strong emotional attachment to the parent of the opposite sex, but the child must then resolve the tensions such emotional attachments create in relations with the parent of the same sex. For example, a boy with strong attachments to his mother may feel hostility toward his father because the father is viewed as a usurper who possesses the mother and thus robs the boy ofexclusive rights to the pleasure provided by the mother. But hostility loward the father is fraught with danger-the father is awesone and, by comparison, the boy is completely powerless. The Oedipus situation is re-

complete identity with God the father and a religious conversion was the end result. The adequacy of Freud's explanation of conversion experiences and his approach to religion generally has predictably been challenged (e.g., see Kovel, 19fl); Meissner, 1984; Zilboorg, 1961). That issue nonrithstanding, the case history just reviewed provides a particularly graphic example of Freud's position with respect to the pervasive role of powerful unconscious forces in human mental operations. Initially, the young doctor might have justified his renunciation of God in terms of his indignation at the fate of the old woman. But, according to Freud, the conversion was hardly the result of rational processes and the doctor's explanation of the conversion cannot be taken at face value. Our so-called rational explanations may themselves be conditioned by forccs that are oulside the realm of immediate consciousness, as illustrated by the earlier example of posthypnotic suggestion. The idea that rational procsses may serve unconscious motives is a blow to many human

pretensions. It is little wonder, then, according to Freud, (191711955) that "the ego does not look favorably upon psychoanalysis and positively refuses to believe in it" (p. 143). Freud, like Copernicus and Darwin, challenged human narcissism. With Copernicus, we were no longer on center stage in the cosmos; with Darwin, we were no longer products of special

the English term instinct is not a satisfactory

Freud's original work. The tetm dive as that term is used in American psychologr, may be closer in meaning to the ierm Tfrb as'"^_ ployed by Freud. Wharever rhe most appro_ priate translation, Freudt concept of fiil X an importart key to his larger approach to motivation. . Freud argued that Trieb has irs origin in a stimulus. It is a stimulus, unlike exrernil stimuli, because it is not momentary. Indeed, it persistslnril it finds satisfaction. F.reud pointed out that the term need may be the besi term to describe the nature of iuch a stimulus. Freud argued that there are four components associared with an instinct. (With thi above cautionary note, we will use the term instinct for the GermanTrieb.) first componnt is the ,rource, which -The refers to somatic processes that give rise to the stimulus in the first place. The somatic pro_ cesses are mechanical or chemicat changei in stimulus rhar will persist and inrensiS. por ei amplq hunger is iniriated by a variety of me_

term Trieb used in

lng, component of an instinct is its object.

The thifd characteristicof an instinct is its airn. Freud (1915/1957a) noted rhat instincts always seek satisfaction through altering the stimulation that gave rise to them in ttrJfirst place. Though sarisfaction is the final goal of every instind, there may be more than one possible means by which such satisfaction is attained. Further, there may be compromises, temporary delays, substitutes, and so forth. The ego obviously plaln a crucial role in assisting with the aim of instincts. . The final, and perhaps the most interest_

ll:

b$y.Such changes consrirure an initiating

attachmenr

stimulus may serve more than one instinct a-nd a given instinct may become attached to a va_ riety of stimulus objects. A particularly strong

through the object that the instinct achieves its-aim. Freud (19t5/1957a) argued rhar the object of an instincr is highly variable. A single

It

is

have? His reply was, .,Theri is obviously

chanical and chemical changes and wiil persist abolished. Satisfaction, however, is always temporary because instincts have a cyclical nalure. Freud. anticipated the question that any reader might raise. How many instincts do we

lixation.

to a specific stimulus is called i

until the source is

riety of vicissitudes. For example, iistincts

sites. The mode

Freud observed thar instincts undergo a va-

may be sublimated, they may be repressed, tney may even be reversed into their oppo_

of their

expression has'iar_

reach-ing conseqUences

health of the individual, so this was a topic of

for the adjustment and

386

CHAPTERI6

I

PSYCHOANALY",

'-",

vicissitudes of the instincts will be clearly evident as we now lurn to some additional dimensions of Freud's theory.

gfeat interest toiFreud. Some

of the

sense of impending doom or a feeling of panic. Neurotic anxiety is more likely when basic drives are persistently

suddenly have

a vague

Anxiety

One of the interesting features of Freud's psycholog is its emphasis on the interplay of tensions that confront every human being. Thus, there are tensions between various components of perscinality, tensions between competing drives, and tensions from the sources of pain and suffering mvered at the beginning of our treatment of Freud's system. Freud believed that there are specific varieties of anxioty associated with some of the important and pervasive tensions that we all must hce.

Obiective Attt@.4 A common anxiety is that associated with objective threats to our wellthe outer world can being, As noted

I

thwarted or bottled up. In the Victorian culrflS6 ef Fupud's day*, there were particularly s*io,Bg lr,ro&ibitions *nd rigid prescriptions regarding the expres$ion of sexualily. A major emphasis in Freud's theory is that if such a poweiful drive is stilled at every turn, then it will find another mode of expression. Neurotic anxiety is one manifestation of powerful instinctual enerry threatening to ovorcome the

ego.

over-present internal conrpanions. We turn now to some of the strategies employed by the ego as ir goes about the rast ofcoping witir tt grear range of rarional anO iirai{onat " fu.ses that play on it.

Defcnse Mechanlsms of the Ego

superego. The ego must also have sufficient strength to deal wiah the harsh tlemands of the world and with the persisrent A"mano, of ii,

t<l some degree

mechanisms.

lorgotten appoinlments, and humor. Freud also believed that repression is involved

tongu_e,

in the other defense

a

khld 0f repressioll that occurs with minimai involvement from the ego. Freud ,"f".r"0 io this fype of repression as pimal repression which refers to a class of ideas ,o pulnfU unj

frorn consciousness ln the first

inces-r

Touq! rhe ego makes use of repression, nray be aided by the superogo. Theie is afso

it

Moral Anxicty. The final type of anxiety, moral anxiety, is a kind ofoounterpart ofneurotic

rage against us, our body is vulnerable to assaults from within and without and, most of all, we can be huirt by other people. Freud acknowledged that'many of our anxieties have a real basis from objective threats. He referred to such anxiety as obfective anxiety.'It is part of the wear and tear of living in a world that is not always friendly. It arises when the ego is threatened by objective forces in the world. Its force is a function of the strength of lhe ego in relation to the Power or perceived power of the objective threat.

Neurolic Arciety.; The anxiety that was of particular concern to Freud was a variety that he called neurotic anxiety, which arises when the

uearlier,

anxiety; however, in this case, it is the irrational demands 0f the superego that threaten to overcome the ego. Like neurotic anxiety, the source of moral anxiety is within the personality, so thers is no escape. originally, the sources of moral anxiety were in the outside world, but in time, the superego incorporates norms, valuos, cusloms, and prohibitions of

society. The superego becomes a kind

ploy admirable merhods as it copdwith "rn_ oan_ gers and anxieties. The

unrortunare o"r"nriu"

ofhealth. Freud believed rhat rhe rgo.un

Earlier, we discussed Freud's beljef that work defense uguinrt in" sources of pain and suffering that we all en_ counter. Freud believed that nothing ties us so closety to reality as our work. The capacitv to w_ork with vigor and joy is, in his view, a mart

unthinkable that they are normilly barred

is the most admirable

and aggression against

sexed parent are included

"fp"iir"in this group.'

placJlde;;; ir,"

of disguises, distortioqs, falsifica tions, Oeniais, and -misrepresentations of reality. W" n; mnsider some of these strategies. Represshn. There is no concept more central to psychoanalysis than the concept of repression..Indeed, Freud ( l9t4ll e57c;' poin tej out that "the theory of repression ii rhe corner_ stone on which the whole structure ofpsycho_ analysis rests. It is the most essential pan of q. tq), Ttre theory otrepression, orioo"", 11also implies the exislence ol unconscious men_

rtriflgiHl,,xffilt"::

of in-

ternal substitute for the punishment that was onc threatened by the parents. Now, moral anxiety is experienced as guilt over real (or even imagined) departures from internalized values. Obviously, the stronger the superego, the greatr the likelihood of moral anxiety. Furthermore, sometimes the most virtuous

and exemplary people experience the greatest moral anxiety. On the opposite eXtreme, there

lal processes, Repression,

are those who experience almost no moral

anxiety, but such people run the risk of placing their own instinctual program$ ahead of the

rights

of others. Such people obviously risk

ego is threatened by the irralional forces of the id. Thus, unlike objective anxiety, the source of the threat is from within our own personality. Since the source of threat is from within, there is no obvious escape and no

clearly identifiable cause. Neurotic anxiety can therefore have a ubiquitous quality in the sense that it can appear, for no apparent reason, at any time or place. The individual may

being isolated by one means or another. Those with excessive moral anxiety risk living a colorless, truncated, overly controlled, and hollow existence. The varieties of anxiety with their various tradeoffs illustrate the importance of balance in the three systems of personality. The health

consciousness and into the unconscious realm. The conrent of the unconscious mind is hr;;it repressed material. In describing the un6nsciorr$ arena, Gay (l9gg) cornpired

thal dangerous or anxiety_provoking tlloughts, memories, or perceptions are forded ou"t oi

as a defense, means

and adjustment of the individual require a channeled flow of energr from the id and the

maxlmum-scurity prison holding antisocial rnmates . . . [such inmates are] heavily guard_ ed, but barely kept under control and f6rever ro escape" (p. l2S). For mosr of us, :,llelptinC tne inmates or their representatives do in faci a continuing basis and rhey are -. :Try manltested in tlream content, slips

'l'l

.

it i; ;;

price in anxiety.

able or when they provoke anxiety, they m'ay be repressed. The repressed maieriali mau then be expressed in rhe claim rhat rhe repuOi_ ated motive is operating in others. por eLm_ ple, a marital partner tempted to be unfaithftrl Tl.{..:.u-r" rhe other parrner of having un_ faithful fantasies. Aggiessive individuais or even aggressive groufs may claim that the real source of aggression is in others. Those with repressed voyeuristic curiosities may worry about the moral breakdown of society anrl thi excessive interest ofothers in pornography. In projection, rhe ego is protected becauje it does not have to own the motives ancl iOeas that provoke anxiety. The price for such prois high because reatiry is ::,r]"i, hgwever, severely distorred. What could have been faced as neurotic or moral anxiety i. no* Arc_ guised as objective anxiety. For ixample, the anger or the perceived unfaithfulness tlraf on" norr projects onto another will exact its own

Projection. Projection occurs when personal faults or weaknesses are externaliz"d or as_ cribed to objecm, events, or ofter peoDte. When personal motives or ideas uru un'..Jji_

oi fhe

Regressions may be brief and episoOic or,"in

tne reinstatement of attitudes and behaviors that were characteristic of that ,urfi"i,tug".

:,:1."u1

Regression. Regression involves the return or to an earlier stage of developmenr and

Вам также может понравиться

- Energy and StyffДокумент18 страницEnergy and StyffscrappyvОценок пока нет

- Effect of Freud On AnthropologyДокумент5 страницEffect of Freud On AnthropologysadeqrahimiОценок пока нет

- E Reference LibraryДокумент72 страницыE Reference LibraryCheryl Morris WalderОценок пока нет

- Social Science Nmat ReviewerДокумент13 страницSocial Science Nmat ReviewerSay77% (13)

- Sigmund Freud: Early Years & EducationДокумент14 страницSigmund Freud: Early Years & Educationgrizz teaОценок пока нет

- Enrico Fermi.. and The Revolutions in Modern PhysicsДокумент121 страницаEnrico Fermi.. and The Revolutions in Modern Physicsilyesingenieur100% (2)

- Assessment For LearningДокумент42 страницыAssessment For LearningAbu BasharОценок пока нет

- Understanding Your Aptitudes PDFДокумент92 страницыUnderstanding Your Aptitudes PDFstutikapoorОценок пока нет

- An Introduction To Object Relations 1997 Chap 1.compressedДокумент11 страницAn Introduction To Object Relations 1997 Chap 1.compressedCarlota BoduОценок пока нет

- EFL Phonics - New Edition - Teaching Aids PDFДокумент9 страницEFL Phonics - New Edition - Teaching Aids PDFTanya ArguetaОценок пока нет

- Kenya Registered NgosДокумент604 страницыKenya Registered NgosfoundationsОценок пока нет

- PsychoanalysisДокумент67 страницPsychoanalysisNabil KhanОценок пока нет

- Isku CatalogueДокумент28 страницIsku CatalogueIDrHotdogОценок пока нет

- Martin S. Bergmann 2008 - The Mind Psychoanalytic Understanding Then and Now PDFДокумент28 страницMartin S. Bergmann 2008 - The Mind Psychoanalytic Understanding Then and Now PDFhioniamОценок пока нет

- The Interpretation of Dreams PDFДокумент3 страницыThe Interpretation of Dreams PDFThiОценок пока нет

- Deutsch Psychoanalysis Sexual Function WomenДокумент159 страницDeutsch Psychoanalysis Sexual Function WomenGraziella Cardinali100% (1)

- Study Guide to the Introductory Lectures of Sigmund FreudОт EverandStudy Guide to the Introductory Lectures of Sigmund FreudОценок пока нет

- Investiture Script 2018Документ3 страницыInvestiture Script 2018ethel t. revelo85% (13)

- Jaap Bos, Leendert Groenendijk, The Self-Marginalization of Wilhelm Stekel - Freudian Circles Inside and Out (Path in Psychology) 2006Документ234 страницыJaap Bos, Leendert Groenendijk, The Self-Marginalization of Wilhelm Stekel - Freudian Circles Inside and Out (Path in Psychology) 2006Liviu MocanuОценок пока нет

- European Psychotherapy 2014/2015: Austria: Home of the World's PsychotherapyОт EverandEuropean Psychotherapy 2014/2015: Austria: Home of the World's PsychotherapyОценок пока нет

- Knowledge in a Nutshell: Sigmund Freud: The complete guide to the great psychologist, including dreams, hypnosis and psychoanalysisОт EverandKnowledge in a Nutshell: Sigmund Freud: The complete guide to the great psychologist, including dreams, hypnosis and psychoanalysisОценок пока нет

- Revolution in Mind: The Creation of PsychoanalysisОт EverandRevolution in Mind: The Creation of PsychoanalysisРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (7)

- Sigmund Freud 1Документ13 страницSigmund Freud 1NicoleОценок пока нет

- Automated Software TestingДокумент602 страницыAutomated Software Testingkaosad100% (2)

- Jung contra Freud: The 1912 New York Lectures on the Theory of PsychoanalysisОт EverandJung contra Freud: The 1912 New York Lectures on the Theory of PsychoanalysisРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Totem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (Annotated)От EverandTotem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (Annotated)Оценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan Kinetic-Molecular TheoryДокумент2 страницыLesson Plan Kinetic-Molecular Theoryapi-27317852680% (5)

- Eli ZaretskyДокумент21 страницаEli ZaretskylauranadarОценок пока нет

- Sigmund FreuddДокумент14 страницSigmund FreuddJoeyjr LoricaОценок пока нет

- Freud and RyleДокумент44 страницыFreud and Rylerustie espiritu100% (1)

- Freud, Sigmund - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyДокумент19 страницFreud, Sigmund - Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyozuluokeoluchukwuОценок пока нет

- BAUER Psychoanalysisglbtq Encyclopedia20042015Документ11 страницBAUER Psychoanalysisglbtq Encyclopedia20042015Mark James Dela CruzОценок пока нет

- 002Документ16 страниц002Carlos Patricio Ortega SuárezОценок пока нет

- Totem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Resemblances between the Psychic Lives of Savages and NeuroticsОт EverandTotem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Resemblances between the Psychic Lives of Savages and NeuroticsОценок пока нет

- Daguplo - Uts Task 2 (Philosophers)Документ7 страницDaguplo - Uts Task 2 (Philosophers)Carl GomezОценок пока нет

- Brown 1940Документ11 страницBrown 1940CroBut CroButОценок пока нет

- Biography of Sigmund FreudДокумент5 страницBiography of Sigmund FreudshairanicolecabuenasОценок пока нет

- D. F. Verene - Vico and FreudДокумент7 страницD. F. Verene - Vico and FreudHans CastorpОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud: "Freud" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, See Freud (Disambiguation)Документ16 страницSigmund Freud: "Freud" Redirects Here. For Other Uses, See Freud (Disambiguation)ZIM6662Оценок пока нет

- The Introduction of Sigmund FreudДокумент7 страницThe Introduction of Sigmund FreudDarwin Monticer ButanilanОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud Male Sexual DisfunctionsДокумент8 страницSigmund Freud Male Sexual DisfunctionsAna Carol MoszkowiczОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) : Father of Psychoanalysis: Medicine in StampsДокумент2 страницыSigmund Freud (1856-1939) : Father of Psychoanalysis: Medicine in StampsUlfi KhoiriyahОценок пока нет

- Sigmund FreudДокумент39 страницSigmund FreudHanis RazakОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsОт EverandSigmund Freud - Quotes Collection: Biography, Achievements And Life LessonsОценок пока нет

- Sigmund FreudДокумент16 страницSigmund FreudSandeep SharatОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud: Navigation Search Freud (Disambiguation)Документ19 страницSigmund Freud: Navigation Search Freud (Disambiguation)sanda3k100% (1)

- Totem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Resemblances between the Psychic LIves of Savages and NeuroticsОт EverandTotem and Taboo (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading): Resemblances between the Psychic LIves of Savages and NeuroticsРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (3)

- Psychology UnhДокумент18 страницPsychology UnhJurisnikОценок пока нет

- Report On Sigmund FreudДокумент3 страницыReport On Sigmund FreudKenethhhОценок пока нет

- The Reach of Mind - Essays in Memory of Kurt Goldstein - Marianne L. Simmel (Auth.), Marianne L. Simmel (Eds.) - 1, 1968 - Springer-Verlag Berlin - 9783662402658 - Anna's ArchiveДокумент297 страницThe Reach of Mind - Essays in Memory of Kurt Goldstein - Marianne L. Simmel (Auth.), Marianne L. Simmel (Eds.) - 1, 1968 - Springer-Verlag Berlin - 9783662402658 - Anna's Archive張浩淼Оценок пока нет

- Ernest Harms, C.G. Jung - Defender of Freud and The JewsДокумент32 страницыErnest Harms, C.G. Jung - Defender of Freud and The JewsHeráclito Aragão PinheiroОценок пока нет

- Textos PsicologÃ-a II - 2018Документ11 страницTextos PsicologÃ-a II - 2018Gabriel Alejandro AdragnaОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud 2Документ4 страницыSigmund Freud 2carlo anganaОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud: Development of PsychoanalysisДокумент3 страницыSigmund Freud: Development of PsychoanalysisRoibu Andrei ClaudiuОценок пока нет

- Psychoanalysis of MythДокумент31 страницаPsychoanalysis of Myththalesmms100% (3)

- A Counterblast in The War On FreudДокумент14 страницA Counterblast in The War On FreudSophie YaniwОценок пока нет

- Authentic Existence According To MartinДокумент16 страницAuthentic Existence According To MartinEmmanuelОценок пока нет

- Major Developmental TheoristДокумент6 страницMajor Developmental TheoristjamesОценок пока нет

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)От EverandBeyond the Pleasure Principle (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Оценок пока нет

- And Circles.1: Us MoreДокумент19 страницAnd Circles.1: Us MoreVictoria CoslОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Frued DostoevskyДокумент2 страницыSigmund Frued DostoevskyJake Arman PrincipeОценок пока нет

- Grof 24 FormattedДокумент24 страницыGrof 24 Formattedfreitas.pianoОценок пока нет

- Sigmund Freud - BiographyДокумент2 страницыSigmund Freud - BiographyFREIMUZICОценок пока нет

- Foaie Colectiva de Prezenta: Padure LoredanaДокумент4 страницыFoaie Colectiva de Prezenta: Padure LoredanascrappyvОценок пока нет

- Ordinul IezuitДокумент2 страницыOrdinul IezuitscrappyvОценок пока нет

- MORMONIIДокумент4 страницыMORMONIIscrappyvОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Music EducationДокумент7 страницContemporary Music EducationHannah Elizabeth GarridoОценок пока нет

- Feeling Happy American English TeacherДокумент5 страницFeeling Happy American English TeacherFern ParrellОценок пока нет

- Why Problem-Solving Skills Are ImportantДокумент5 страницWhy Problem-Solving Skills Are Importantibreex alyyОценок пока нет

- High School CarpentryДокумент4 страницыHigh School CarpentryFlyEngineerОценок пока нет

- Soal Bahasa InggrisДокумент4 страницыSoal Bahasa InggrisMuhammadNurFauziОценок пока нет

- 2014 Nat Comprehension Check-Edited 1.7.14Документ2 страницы2014 Nat Comprehension Check-Edited 1.7.14Dhan Bunsoy100% (2)

- UndSelf Course Outline 2019-2020Документ4 страницыUndSelf Course Outline 2019-2020Khenz MistalОценок пока нет

- Arkeologi Islam NusantaraДокумент4 страницыArkeologi Islam NusantaraMuhammad Ma'ruf AsyhariОценок пока нет

- UIL Class 5A, Division I Football RealignmentДокумент1 страницаUIL Class 5A, Division I Football RealignmentHouston ChronicleОценок пока нет

- Steve Imparl CV 20080430Документ8 страницSteve Imparl CV 20080430steve.imparlОценок пока нет

- Basic 01Документ7 страницBasic 01gabriela fernandezОценок пока нет

- Effective Parenting in A Defective World: Book Discussion GuideДокумент6 страницEffective Parenting in A Defective World: Book Discussion GuidesamyОценок пока нет

- School CoordinatorДокумент3 страницыSchool Coordinatormargie reonalОценок пока нет

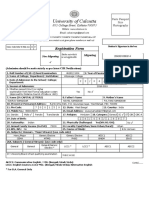

- University of Calcutta: Registration FormДокумент2 страницыUniversity of Calcutta: Registration FormSourav SamaddarОценок пока нет

- English 7 Action Plan 2020 2021Документ4 страницыEnglish 7 Action Plan 2020 2021Laurence MontenegroОценок пока нет

- MAPEH (Music) : Quarter 1 - Module 4: Rhythmic PatternsДокумент25 страницMAPEH (Music) : Quarter 1 - Module 4: Rhythmic PatternsNaruffRalliburОценок пока нет

- EnglishLanguageComparisonTable PDFДокумент1 страницаEnglishLanguageComparisonTable PDFMobashar LatifОценок пока нет

- Blue Ocean StrategyДокумент15 страницBlue Ocean StrategyRushil ShahОценок пока нет

- 1 COPY DOUBLE Teaching Kids Lesson Plan SportДокумент4 страницы1 COPY DOUBLE Teaching Kids Lesson Plan SportThe IELTS TutorОценок пока нет

- Shooq Ali 201600097Документ4 страницыShooq Ali 201600097api-413391021Оценок пока нет