Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

390 P Closing Brief

Загружено:

Eugene D. LeeИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

390 P Closing Brief

Загружено:

Eugene D. LeeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

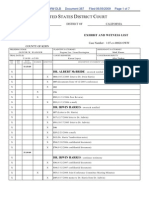

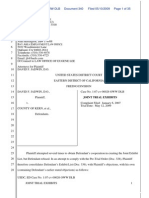

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 1 of 21

1 LAW OFFICE OF EUGENE LEE

Eugene D. Lee (SB#: 236812)

2 555 West Fifth Street, Suite 3100

Los Angeles, CA 90013

3 Phone: (213) 992-3299

Fax: (213) 596-0487

4 email: elee@LOEL.com

5 Joan Herrington, SB# 178988

BAY AREA EMPLOYMENT LAW OFFICE

6 5032 Woodminster Lane

Oakland, CA 94602-2614

7 Telephone: (510) 530-4078

Facsimile: (510) 530-4725

8 Email: jh@baelo.com

Of Counsel to LAW OFFICE OF EUGENE LEE

9

Attorneys for Plaintiff

10 DAVID F. JADWIN, D.O.

11 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

12 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

13

14 DAVID F. JADWIN, D.O., Civil Action No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

15 Plaintiff, PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF

16 v. Trial: May 14, 2009

17 COUNTY OF KERN, Complaint Filed: January 6, 2007

18 Defendants.

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 1

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 2 of 21

1 Plaintiff hereby submits this closing brief, including legal positions, findings of fact and

2 conclusions of law, pursuant to the Court’s order of June 5, 2009 (Doc. 385).

3 I. PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS CLAIM.

4 A. Issues

5 As established by the parties, the issues to be determined at this time are:

6 1) Whether Plaintiff had a constitutionally protectable interest in active duty (or avoiding

7 placement on administrative leave).

8 2) Whether Defendant Kern County provided Plaintiff with adequate procedural due process

9 when placing Plaintiff on administrative leave.

10 B. Plaintiff’s Legal Position

11 Plaintiff contends that he had a constitutionally protectable interest in active duty and avoiding

12 placement on administrative leave. Defendant Kern County’s decision to place Plaintiff on

13 administrative leave on December 7, 2006 denied Plaintiff the opportunity to earn per-patient

14 professional fees, which had historically amounted to over $134,987 per year since 2002. Plaintiff’s

15 contract of November 12, 2002 expressly provided that Plaintiff would earn professional fees as a

16 material part of his total compensation.

17 Plaintiff contends that Defendant Kern County gave Plaintiff no procedural due process

18 whatsoever, whether pre- or post-deprivation.

19 C. Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact

20 1) Plaintiff’s contract of November 12, 2002 (“Employment Contract”) expressly provided

21 that Plaintiff would earn professional fees as a material part of his total compensation by Defendant.

22 Trial Exhibit 139.002 (Agreement for Professional Services of David F. Jadwin, dated 11/12/02)

23 provides:

24 Total compensation for Core Physicians will be composed of a base salary paid by the

County, professional fee payments from third-party payors, and potential other

25 income generated due to the individual's status as a physician. These three sources of

income shall be referred to in this Agreement as total Core Physician compensation

26 [emphasis added].

27 The Employment Contract goes on to devote an entire page to discussion of “Professional Fees”, from

28 Exh. 139.004 to 139.005.

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 1

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 3 of 21

1 2) Plaintiff’s contract was amended on October 3, 2006, to institute a base pay reduction in

2 accordance with his removal from chairmanship. See Exh. 283. The amendment did not change the fixed

3 term of the contract, which was to expire on October 4, 2007.

4 3) Plaintiff’s professional fee compensation had historically amounted to $134,987 per year

5 since 2002. Both Plaintiff and Plaintiff’s forensic economist, Stephanie Rizzardi, testified at trial that

6 this was the case. See Exh. 451.3 (Rizzardi Calculation of Economic Losses). Defendant put on no

7 evidence disputing this fact.

8 4) Then-Interim-CEO David Culberson decided to place Plaintiff on administrative leave,

9 effective December 7, 2006. Mr. Culberson testified at trial that this was the case. Defendant never

10 disputed this fact.

11 5) During the administrative leave, Plaintiff was prohibited from going to the hospital or

12 contacting any hospital employees. See Exh. 317.001 (Culberson Letter to Plaintiff, dated 12/7/06 re

13 administrative leave). Plaintiff testified at trial that he complied fully with this prohibition.

14 6) In order to earn professional fees, Plaintiff needed to be physically present at the hospital.

15 Defendant never disputed this fact.

16 7) Placement on administrative leave deprived Plaintiff of $116,501 in professional fees.

17 Both Plaintiff and Plaintiff’s forensic economist, Stephanie Rizzardi, testified at trial that this was the

18 case. See Exh. 451.3 (Rizzardi Calculation of Economic Losses). Defendant put on no evidence

19 disputing this fact.

20 8) In placing Plaintiff on administrative leave, Defendant relied specifically upon the “Kern

21 County Policies and Administrative Procedures Manual” (Exh. 501) (“Manual”), a County-ratified

22 policy. See Exh. 317.001 (Culberson Letter to Plaintiff, dated 12/7/06 re administrative leave).

23 9) Plaintiff’s Employment Contract specified that he was subject to “all applicable KMC

24 and County policies and procedures”, such as the Manual. See Exh. 139.014.

25 10) Section 124.3 of the Manual provided that Plaintiff could be placed on paid

26 administrative leave with pay under certain specified circumstances including when “the department

27 head determines that the employee is engaged in conduct posing a danger to County property, the public

28 or other employees, or the continued presence of the employee at the work site will hinder an

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 2

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 4 of 21

1 investigation of the employee's alleged misconduct or will severely disrupt the business of the

2 department.” See Exh. 104.001.

3 11) No provision of Plaintiff's employment contract granted the County the right to place

4 Plaintiff on administrative leave.

5 12) Plaintiff was never informed of the nature of the charges against him leading to his being

6 placed on administrative leave, before or after being placed on such administrative leave. Plaintiff

7 testified at trial that this was the case, and that it was only during discovery in this action that he finally

8 learned of the alleged reasons why he was placed on administrative leave. In the letter placing Plaintiff

9 on administrative leave, Mr. Culberson stated only that he was being placed on administrative leave

10 “pending resolution of a personnel matter”. See Exh. 317.001 (Culberson Letter to Plaintiff, dated

11 12/7/06 re administrative leave).P Defendant’s witness, Philip Dutt, seemed to suggest at trial that Exh.

12 307.001 (Email from Dutt to Plaintiff, dated 12/7/06) provided such notice; however, Dr. Dutt also

13 testified at trial that when he subsequently sent Plaintiff an email taking him off call for the weekend

14 (Exh. 316.001), he had no knowledge that Mr. Culberson had placed Plaintiff on administrative leave,

15 nor any specific knowledge that administrative leave was even being considered by Mr. Culberson.

16 13) Plaintiff was never provided with a hearing, or notice thereof, before or after being placed

17 on administrative leave. Plaintiff testified at trial that this was the case, and that it was only during

18 discovery in this action that he finally learned of the alleged reasons why he was placed on

19 administrative leave. Defendant put on no evidence disputing this fact.

20 14) Plaintiff was never provided an opportunity to respond to the charges against him, before

21 or after being placed on administrative leave. Plaintiff testified at trial that this was the case, and that it

22 was only during discovery in this action that he finally learned of the alleged reasons why he was placed

23 on administrative leave. Defendant put on no evidence disputing this fact.

24 D. Plaintiff’s Proposed Legal Conclusions

25 1. Whether Plaintiff had a constitutionally protectable interest in active duty (or avoiding

placement on administrative leave)

26

To have a viable claim then, Plaintiff must demonstrate that his property interest in continued

27

employment included a property right in "active duty," Deen v. Darosa, 414 F.3d 731, 734 (7th Cir.

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 3

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 5 of 21

1 2005), or, as the Ninth Circuit has suggested, a "property interest in avoiding placement on

2 administrative leave with pay." Qualls v. Cook, 245 F. App'x 624, 625 (9th Cir. 2007).

3 The limitations on placing an employee on administrative leave contained in the Manual (and the

4 Employment Contract’s silence on the topic) significantly constrained the County's authority, thus

5 establishing a claim that Plaintiff's property right in continued employment included a property right in

6 active duty.

7 Moreover, given that his contract expressly provided that he could earn professional fees and that

8 his fees would be a part of his total compensation, both Plaintiff and the County certainly envisioned

9 that Plaintiff would be in a position to earn professional fees so that Plaintiff could obtain the fruits of

10 his bargain.

11 Given Plaintiff's history of professional fee earnings, it cannot be said that his loss of potential

12 professional fees is de minimis harm.

13 By specifying the grounds on which Plaintiff could be placed on paid administrative leave, and

14 by not contractually providing for any other right to place Plaintiff on paid administrative leave, the

15 County implicitly limited its authority to place Plaintiff on paid leave to the specific reasons. See

16 Sanchez v. City of Santa Ana, 915 F.2d 424, 429 (9th Cir. 1990).

17 The Supreme Court has not decided whether procedural due process protections extend to

18 employee discipline short of termination. See Gilbert v. Homar, 520 U.S. 924, 928-29. However, the 9th

19 Circuit has suggested that they extend to situations in which an employee with a protected interest in

20 continued employment is suspended with pay. See Qualls v. Cook, 245 Fed. Appx. 624, 626 (9th Cir.

21 Nev. 2007) (citing Peacock v. Bd. of Regents of Univ. and State Coll., 510 F.2d 1324, 1326-30 (9th Cir.

22 1975)). In both Qualls and Peacock, because the plaintiff continued to be paid during the administrative

23 leave, the court adjudged the plaintiff’s property interest in active duty to be “very little, if any”. Qualls,

24 245 Fed. Appx. At 626. In contrast, Plaintiff’s placement on administrative leave caused him to lose

25 more than $100,000 in professional fees, a far more substantial economic injury than was clearly the

26 case in Qualls and Peacock. Given the 9th Circuit found a property interest in active duty in Peacock and

27 Qualls, there should be no question that Plaintiff had a property interest in active duty in the instant case.

28 There is some California authority that a physician who is employed under a fixed term contract

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 4

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 6 of 21

1 with a County and who is acting lawfully and complying with the terms of his contract cannot be

2 prevented “from performing the duties incumbent on him” for arbitrary reasons. Grindley v. Santa Cruz

3 County, 4 P. 390, 393 (Cal. 1884). While ancient and in no way dispositive, this case lends support to

4 the position that, by having a fixed term contract with the County with a general property right in

5 continued employment, Plaintiff may have had a concomitant property right in active duty during the

6 term of his employment.

7 2. Whether Defendant Kern County provided Plaintiff with adequate procedural due process

when placing Plaintiff on administrative leave

8

Defendant provided Plaintiff with no due process whatsoever, much less adequate due process,

9

before or after placing him on administrative leave on December 7, 2006.

10

E. Conclusion Re Due Process Claim

11

Based on the foregoing, Plaintiff respectfully requests that the Court find Defendant Kern

12

County liable in the amount of $116,501, pursuant to 42 U.S.C. 1983, for depriving Plaintiff of property

13

without adequate due process in connection with his placement on administrative leave on December 7,

14

2006.

15

16 II. MEDICAL LEAVE INTERFERENCE CLAIM

17 A. Issues

18 1) Whether Defendant forced Plaintiff to take more medical leave than was medically

19 necessary.

20 2) Whether Defendant improperly designated some of Plaintiff's medical leave as "Personal

21 Necessity Leave" by miscalculating the number of hours of medical leave to which Plaintiff

22 was entitled, including penalties for Defendant's failure to provide Plaintiff with notice of

23 designation of the extension of his leave as medical leave, and a written guarantee of

24 reinstatement.

25 B. Plaintiff’s Legal Position

26 Plaintiff contends that Defendant denied him his request for reduced work schedule medical

27 leave by forcing him to take more leave that was medical necessary by converting his reduced work

28 schedule leave into full-time leave on April 28, 2006. Plaintiff also contends that Defendant interfered

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 5

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 7 of 21

1 with his right to medical leave by miscalculating the number of hours to which Plaintiff was entitled,

2 and by failing to provide Plaintiff with notice of designation of the extension of his leave as medical

3 leave, and a written guarantee of reinstatement.

4

C. Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact

5

1) It is undisputed that Plaintiff exhausted all of his administrative remedies.

6

2) It is undisputed that Plaintiff was eligible for medical leave as of December 16, 2005.

7

3) Plaintiff had medical leave available to him at the time that he applied for an extension of his

8

medical leave.

9

4) Defendant's then Director of Human Resources (Sandra Chester) testified that, under the

10

circumstances, Plaintiff provided adequate notice of both his need for medical leave and his

11

need for an extension of his medical leave.

12

5) Plaintiff needed to take medical leave for his own serious health condition (chronic

13

depression).

14

6) It is undisputed that chronic depression is a serious health condition.

15

7) Dr. Riskin's certifications establish that Plaintiff had a medical need that was best

16

accommodated through a reduced work schedule leave.

17

8) Defendant's then Director of Human Resources (Sandra Chester) testified that both of

18

Plaintiff's certifications for his need for a reduced work schedule leave were adequate.

19

9) Defendant denied Plaintiff's request for an extension of his reduced work schedule medical

20

leave.

21

10) Defendant interfered with Plaintiff's right to a reduced work schedule medical leave by

22

forcing him to take more leave than was medically necessary.

23

11) Plaintiff was capable of working part-time from at least June 12, 2006 to June 16, 2006.

24

12) Parties stipulated that Plaintiff's medical leave allotment was exhausted on June 16, 2006.

25

13) Defendant interfered with Plaintiff's right to medical leave by miscalculating the number of

26

hours of reduced work schedule medical leave to which Plaintiff was entitled, and failing to

27

notify Plaintiff that his March 16 to June 16, 2006 leave was FMLA/CFRA qualifying leave

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 6

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 8 of 21

1 and to guarantee him reinstatement following this leave in writing.

2

D. Plaintiff’s Proposed Legal Conclusions

3

It is “unlawful for any employer to interfere with, restrain, or deny the exercise of or the attempt

4

to exercise, any right provided under this subchapter.” 29 U.S.C. § 2615(a); Cal. Gov’t Code §

5

12945.2(a); Faust v. California Portland Cement Co. 150 Cal. App. 4th 864, 885 (2007) (recognizing

6

that CFRA incorporates an interference claim from FLMA); Liu, 347 F.3d at 1132 n.4 (recognizing that

7

leave denial/interfence claims under the CFRA and FMLA can be analyzed together “[s]ince CFRA

8

adopts the language of the FMLA and California state courts have held that the same standards apply.”)

9

“A violation of the FMLA simply requires that the employer deny the employee’s entitlement to

10

FMLA leave.” Liu v. Amway Corp. (9th Cir. 2003) 347 F.3d 1125, 1135.

11

Here, it is undisputed that Plaintiff exhausted any and all administrative remedies, that Defendant

12

was a covered employer, that Plaintiff was eligible for medical leave as of December 16, 2005 and had

13

medical leave available to him on March 16, 2006 when he first applied for an extension of his medical

14

leave, so was still eligible for medical leave. [2 C.C.R. § 7297.0(e)(1); Exh. 235, 060316 Email Jadwin-

15

Bryan; Doc 386, Jury Instructions at 18:5-7]. Further, it is undisputed that Plaintiff still had medical

16

leave available to him on April 28, 2006, when Defendant converted his reduced work schedule medical

17

leave to full-time medical leave. [Doc. 369, Plaintiff's Request for Judicial Notice Nos. 8-9, 12, 16, 17,

18

& 25 granted on the record at trial; see also Doc 386, Jury Instructions at 18:5-7; Exh. 251, 060428

19

Memo Bryan-Jadwin]. It is also undisputed that Plaintiff's chronic depression was a serious health

20

condition in that his testimony, and that of Dr. Reading, that Plaintiff sought treatment from his

21

psychiatrist once a week during his medical leave and took prescribed medication for it was uncontested.

22

2 C.C.R. § 7297.49(b)(2).

23

Sandra Chester, Defendant's then Director of Human Resources testified that Plaintiff's email to

24

Peter Bryan on March 16, 2006 consisted sufficient notice of Plaintiff's need for an extension of his

25

medical leave, and should have resulted in Human Resources Department sending him a FMLA/CFRA

26

information packet, including another Request for Leave form and notice of Defendant's policy of

27

requiring recertification of his need for an extension of his medical leave, but did not do so. [Exh. 235,

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 7

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 9 of 21

1 060316 Email Jadwin-Bryan]. Sandra Chester further testified that Plaintiff's Request for Leave dated

2 April 26, 2006 and Dr. Riskin's accompanying certification were a timely response to her letter of April

3 20, 2006. [Exh. 561, 060420 Letter Chester-Jadwin; Exh. 562 060426 Certification by Dr. Riskin; Exh.

4 563, 060426 Request for Leave].

5 Thus, Plaintiff has established all of the threshold requirements for the granting of his request for

6 an extension of his medical leave.

7 3. Defendant Denied Plaintiff's Request for a Reduced Work Schedule Leave.

8 “An employee may not be required to take more FMLA leave than necessary to address the

9 circumstance that precipitated the need for the leave.” 29 C.F.R. § 825.203(d).

10 Both of Dr. Riskin's certifications supporting Plaintiff's requests for a reduced work schedule

11 medical leave and an extension of his reduced work schedule medical leave indicate that Plaintiff had a

12 medical need that was best accommodated through a reduced work schedule leave. 29 C.F.R. §

13 825.202(b); Exhs. 544 & 562 (Certifications). Sandra Chester (then Director of Human Resources)

14 testified that both of Plaintiff's certifications of his need for a reduced work schedule medical leave were

15 adequate.

16 Moreover, "[t]he employer should inquire further of the employee if it is necessary to have more

17 information about whether CFRA leave is being sought by the employee and obtain the necessary details

18 of the leave to be taken." Gibbs v. American Airlines, Inc. (1999) 74 Cal.App.4th 1, 6-7 (same); Mora v.

19 Chem-Tronics, Inc. (S.D. Cal. 1998) 16 F.Supp.2d 1192, 1209-1210 ("...courts have found that notice

20 may be sufficient when employees call employers to tell them that they or their children are sick and

21 they will be absent from work…"); Mora v. Chem-Tronics, Inc. (S.D. Cal. 1998) 16 F.Supp.2d 1192,

22 1209 ("Mr. Mora need not show that he expressly asserted rights under FMLA or even mentioned

23 FMLA, but that he stated leave was needed. If further information was needed to determine whether the

24 leave requested qualified under the FMLA, it was Chem-Tronic’s responsibility to inquire further of Mr.

25 Mora for that information.")

26 Further, Defendant is estopped from arguing that it was entitled to deny Plaintiff's request for a

27 reduced work schedule medical leave because his certifications of his need for a reduced work schedule

28 medical leave were ambiguous and confusing.

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 8

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 10 of 21

1 29 CFR § 825.301(f) provides:

2 "(f) If an employer fails to provide notice in accordance with the provisions of this

section, the employer may not take action against an employee for failure to comply

3 with any provision required to be set forth in the notice."

4 2 C.C.R. § 7297.4(a) (5) similarly provides:

5 An employer shall give its employees reasonable advance notice of any notice

requirements which it adopts. The employer may incorporate its notice requirements in

6 the general notice requirements in section 7297.9 and such incorporation shall constitute

"reasonable advance notice." Failure of the employer to give or post such notice shall

7 preclude the employer from taking any adverse action against the employee, including

denying CFRA leave, for failing to furnish the employer with advance notice of a need

8 to take CFRA leave.

9 Accordingly, since Defendant failed properly notify Plaintiff that he must provide additional

10 medical verification to support his leave request (and the consequences for failing to provide it),

11 Defendant cannot now argue that Plaintiff was not entitled to leave because of confusing or inadequate

12 medical documentation. This rational conclusion is supported by the federal decision in Sims. v.

13 Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District, (N.D. California 1998) 2 F.Supp.2d 1253.

14 In this case, Mr. Sims, a bus driver, was fired for excessive absenteeism. He believed that some

15 of the absences counted against him were because of his bad back, which he felt was a serious health

16 condition under both the CFRA and the FMLA. Id. at 1256. In support of his leave request, Mr. Sims

17 had submitted various documents from doctors and a chiropractor. AC Transit argued that a portion of

18 Mr. Sims absences were not FMLA-qualified because he went to a chiropractor who did not meet the

19 definition of a "health care provider" under the FMLA. Id. at 1265-1266. (It is important to note that AC

20 Transit was correct! The chiropractor Mr. Sims visited did not perform a "manual manipulation of the

21 spine to correct a sublaxation as demonstrated by X-ray to exist", the specific procedure required to

22 qualify the chiropractor as a "health care provider" under the FMLA. Id.)

23 However, applying 29 CFR § 825.301(f), the court held that AC Transit could not argue the

24 insufficiency of the chiropractor visits because AC Transit had not first met its notice requirements.

25 Specifically the court stated:

26 "AC Transit concedes that it never informed Sims that his certification was inadequate

in any way. It had an obligation, however, to do so. Nor did AC Transit ever notify Sims

27 in writing that he had to provide medical certification in this particular case or of the

consequences of his failing to do so. The regulations provide that '[a]n employer must

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 9

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 11 of 21

1 give written notice of a requirement for medical certification . . . in a particular case.' 29

CFR § 825.305(a)." Id. at 1266.

2

3 The court added, citing and approving 29 CFR § 825.301(f):

4 "'If an employer fails to provide notice in accordance with the provisions of this section,

the employer may not take action against an employee for failure to comply with any

5 provision required to be set forth in the notice.'" Id. at 1266.

6 Accordingly, AC Transit could not argue that Mr. Sims did not qualify for FMLA leave. Id. at

7 1266-1267.

8 The Sims, supra, ruling and 29 CFR § 825.301(f) make perfect sense. If an employer is

9 suspicious about an employee's leave request, the employer is permitted, upon proper written notice to

10 the employee, to seek medical certification. 2 C.C.R. § 7297.4(b); 29 C.F.R. § 825.305(a). If the

11 employer believes that the medical certification presented is suspect, the employer is permitted to

12 request clarification and authentication or a second opinion. 2 C.C.R. § 7297.4(b)(2)(A); 29 C.F.R. §

13 825.307(a). Renita Nunn testified that none of this happened in the case. Plaintiff never submitted

14 additional medical verification of his need for a reduced work schedule medical leave because

15 Defendant never informed him that he needed to do so. Thus, Defendant is estopped from arguing, in the

16 throes of litigation, that Plaintiff's leave request for a reduced work schedule medical leave fails for lack

17 of clear, unambiguous medical certification.

18 Plaintiff's failure to protest immediately Defendant's placement of him on full-time medical leave

19 is legally irrelevant. Both federal and state law recognizes that an employee has non-negotiable rights

20 under FEHA, CFRA, and FMLA that cannot be waived by a private agreement. Gemini Aluminum

21 Corp., 122 Cal.App.4th at 1017 ("‘California's anti-discrimination statutes ... demonstrate California’s

22 intent not to allow its laws to be circumvented by private contracts.’"); see also Jimeno v. Mobil Oil

23 Corp.,, 66 F.3d 1514, 1527-1528 (9th Cir., 1995) ("The third prong of the Miller test, requiring an

24 analysis of whether the state has shown an intent not to allow its prohibition to be altered or removed by

25 private contract, also mandates a finding of no preemption in this matter...the FEHA explicitly

26 establish[es] the right to employment without discrimination as a public policy of this state...Thus, the

27 California FEHA is unlike the Missouri anti-discrimination provision which requires consideration of

28 the employer’s authority under the CBA to make accommodations. [citations omitted. Therefore,

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 10

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 12 of 21

1 [Defendant] cannot assert that [California] is indifferent to negotiation and alteration of the right by

2 private contract, and the answer to the third Miller question must be ‘yes.’"); Cramer v. Consolidated

3 Freightways, Inc. 255 F.3d 683, 696 (9th Cir., 2001) ("Because installation of two-way mirrors is

4 immutably illegal, and freedom from the illegality is a “nonnegotiable state-law right[ ],” a court

5 reviewing plaintiffs' claims that their privacy rights were violated need not interpret the CBA to arrive at

6 its conclusion."]

7 4. Defendant Interfered with Plaintiff's Medical Leave Rights by Mislabeling Some of His

Medical Leave as "Personal Necessity Leave.

8

9 An employer interferes with an employee’s rights under the FMLA by mislabeling an

10 employee’s leave as “personal leave” or something else when, in reality, the leave qualified as FMLA

11 leave. Xin Liu v. Amway Corp., 347 F.3d 1125, 1132 (9th Cir. 2003).

12 Parties had stipulated that Dr. Jadwin's medical leave balance was exhausted on June 16, 2006.

13 [Doc 386, Jury Instructions at 18:5-7]. However, Defendant introduced evidence contrary to this

14 stipulation when it testified by and through Renita Nunn that Plaintiff's medical leave allotment had

15 been miscalculated through an arithmetical error, and he only had 37 hours of 480 hours of medical

16 leave left on April 28, 2006.

17 In fact, Defendant also miscalculated the number of hours of leave it should have allotted to Dr.

18 Jadwin.

19 "…When an employee takes leave on an intermittent or reduced work schedule, only the

amount of leave actually taken may be counted toward the employee leave entitlement.

20 The actual workweek is the basis of the entitlement... if a full-time employee who would

otherwise work 8-hour days works 4-hour days under a reduced leave schedule, the

21 employee would use “1/2” week of FMLA leave…" 29 C.F.R. § 825.205(b)(1).

22 Dr. Jadwin's "standard workweek" was 48 hours per week. [Exh. 267, 060710 Memo Bryan-JCC

23 at No. 2 on 267.001]. Dr. Jadwin testified that he often worked more than 48 hours per week prior to

24 taking medical leave. In other words, Dr. Jadwin was entitled to at least 576 hours of reduced work

25 schedule leave, not the 480 hours that Defendant allotted to him. [Exh. 267, 060710 Memo Bryan-JCC

26 at No. 8 on 267.002].

27 More significantly, CFRA provides in pertinent part:

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 11

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 13 of 21

1 "Family care and medical leave requested pursuant to this subdivision shall not be

deemed to have been granted unless the employer provides the employee, upon granting

2 the leave request, a guarantee of employment in the same or a comparable position upon

the termination of the leave." Gov't C. § 12945.2(a).

3

In this case, Defendant failed to issue its formal notice designating Plaintiff's leave from March

4

16, 2006 to June 16, 2006 as CFRA/FMLA qualifying leave, and to provide Plaintiff with a written

5

guarantee employment upon termination of the extension of Plaintiff's medical leave. 2 C.C.R. §

6

7297.4(a)(1)(A) & (B); see, e.g. Exh. 229, (Designation Form of 3/2/06)]. Consequently, Plaintiff's

7

request for an extension of his medical leave request was deemed DENIED by operation of law. If

8

leave is denied, it cannot be counted toward the employee’s allotment for the 12 months entitlement

9

period.

10

This conclusion is consistent with 2 C.C.R. § 7297.4. Requests for CFRA Leave: Advance

11

Notice; Certification; Employer Response:

12

(a) Advance Notice.

13 (1) Verbal Notice.

(A) Under all circumstances, it is the employer's responsibility to designate leave, paid

14 or unpaid, as CFRA or CFRA/FMLA qualifying, based on information provided by the

employee or the employee's spokesperson, and to give notice of the designation to the

15 employee.

16 (B) Employers may not retroactively designate leave as "CFRA leave" after the

employee has returned to work, except under those same circumstances provided for in

17 FMLA and its implementing regulations for retroactively counting leave as "FMLA

leave."

18

19 Further, California regulations expressly incorporated federal implementing regulations for

20 FMLA as of 1995, at a time when its pertinent penalty provisions were still unchallenged. [2 C.C.R. §§

21 7297.0(i), 7297.10]. For example, 29 CFR 825 § 825.700(a) provides: “If an employee takes paid or

22 unpaid leave and the employer does not designate the leave as FMLA leave, the leave taken does not

23 count against an employee’s FMLA entitlement.” The California Fair Employment and Housing

24 Commission incorporated this regulation as helpful to implementing California’s policy favoring notice

25 to the employee of all their rights. Federal courts deemed this penalty provision ineffective on the

26 grounds that Congress did not authorize the extension of an employee's medical leave past 12

27 workweeks as a penalty for failing to designate leave as FMLA leave in a timely manner. [Ragsdale v.

28 Wolverine World Wide, Inc., 535 U.S. 81 (2002)]. However, the California Legislature has expressly

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 12

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 14 of 21

1 authorized an extension of an employee's medical leave past 12 workweeks as a penalty for an

2 employer's failure to provide an employee a written guarantee of reinstatement, so this penalty provision

3 for failing to designate leave as CFRA leave remains unaffected by any contrary federal law. Gov't

4 Code § 12945.2. In other words, there is an independent state-based policy reason for continuing to

5 incorporate 825.700(a) into California’s regulatory scheme notwithstanding that federal courts may

6 interpret the FMLA differently.

7 In short, Defendant is deemed to have denied Plaintiff an extension of his CFRA leave from

8 March 16 to June 16, 2006. In addition, Defendant is prohibited from retroactively designating leave

9 already taken as CFRA leave. 2 C.C.R. § 7297.4(a)(1)(B). In other words, from March 16, 2006 until

10 his employment contract expired on October 4, 2007, Plaintiff still had some medical leave allotment

11 available to him, and Defendant was strictly liable to Plaintiff for failing to grant it, and for labeling his

12 leave from June 14, 2006 onwards as personal necessity leave.

13 In any case, pursuant to the parties' stipulation, as of June 14, 2006, when Defendant's former

14 CEO, Peter Bryan, converted Dr. Jadwin's medical leave to personal necessity leave, Plaintiff was still

15 entitled medical leave. [Doc 386, Jury Instructions at 18:5-7; Exh. 251, 060428 Memo Bryan-Jadwin at

16 251.013 (Rule 1202.02 re Personal Necessity Leave); Exh. 261 060613 Memo Bryan-Jadwin at ¶2].

17 Because Defendant mislabeled at least some of Dr. Jadwin's medical leave as "Personal

18 Necessity Leave", Defendant interfered with Plaintiff's medical leave rights.

19

III. PLAINTIFF'S ENTITLEMENT TO INJUNCTIVE RELIEF

20

A. Issues

21

1) Whether Plaintiff is entitled to prospective injunctive relief in the form of an order requiring

22

Defendant to train its staff to proficiency regarding compliance with disability rights under

23

FEHA, and reduced work schedule leave rights and protection against retaliation under

24

CFRA and FMLA.

25

B. Plaintiff’s Legal Position

26

Statutory remedies for violations of FEHA, CFRA, and FMLA include injunctive relief, and

27

expressly provides that training of staff is appropriate prospective relief. [Gov't. C. § 12965(c).

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 13

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 15 of 21

1 C. Plaintiff’s Proposed Findings of Fact

2 1) Defendant failed to train its staff to proficiency regarding compliance with disability rights

3 under FEHA, and reduced work schedule leave rights and protection against retaliation under

4 CFRA and FMLA.

5 2) Defendant's Director of Human Resources (Steven O'Connor), and the "person most

6 qualified" regarding medical leave (Renita Nunn) both testified at trial that an employee was

7 only entitled to 480 hours of medical leave.

8 3) Defendant's former CEO (Peter Bryan) testified at trial that he relied on Director of Human

9 Resources (Steve O'Connor) and Chief County Counsel (Karen Barnes) to ensure that he

10 complied with the law and Defendant's policies in placing Plaintiff on full-time leave from

11 April 28 to October 3, 2006, and in removing Plaintiff from position as Chair of Pathology

12 at Kern Medical Center on July 10, 2006.

13 4) Defendant's former CEO (Peter Bryan) demonstrated his confusion and poor training when

14 he testified at trial that he understood that, after Plaintiff's medical leave balance and six

15 month cumulative leave pursuant to 1201.20 was exhausted purportedly on June 16, 2006, he

16 could protect Plaintiff's continued employment by Defendant only through a 90 day 'Personal

17 Necessity Leave' pursuant to Rule 1202.02.

18 5) According to the calculations of Defendant's Human Resources Department, Dr. Jadwin's six

19 month cumulative leave pursuant to Rule 1201. 20 was not due to be exhausted until August

20 24, 2006. [Exh 267, 060710 Memo Bryan-JCC at 267.052].

21 6) The jury found that Defendant had violated Plaintiff's rights under FEHA by failing to

22 engage in good faith in an interactive process, denying Plaintiff accommodation in the form

23 of part-time work from April 28 to October 3, 2006, removing him from his position as Chair

24 of Pathology on July 10, 2006, creating a hostile work environment, placing Plaintiff on

25 administrative leave on December 7, 2006, and failing to renew his employment contract on

26 October 4, 2007.

27 7) The jury found that Defendant had violated CFRA and FMLA by removing Plaintiff from his

28 position as Chair of Pathology at Kern Medical Center on July 10, 2006, creating a hostile

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 14

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 16 of 21

1 work environment, placing him on administrative leave on December 7, 2006, and failing to

2 renew his employment contract on October 4, 2007.

3 8) Defendant's policies limit the number of hours available for medical leave to 480 hours in

4 violation of 29 C.F.R. § 825.205(b)(1) and 2 C.C.R. § 7297.3. [Exh. 251, Rule 1201.30 at

5 251.008].

6 D. Plaintiff’s Proposed Legal Conclusions

7 “[T]he Supreme Court has indicated that, at least when injunctive relief is sought in federal

8 courts, litigants must generally adduce a ‘credible threat’ of recurrent injury.” LaDuke v. Nelson, 762

9 F.2d 1318, 1323 (9th Cir. 1985) citing City of Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U.S. 95 (1983)]. A later Ninth

10 Circuit case found all requirements for equitable relief standing met where the district court found an

11 unconstitutional policy or practice of the defendant. Armstrong v. Davis, 275 F.3d 849, 861 (9th Cir.

12 2001). The Armstrong Court explained the key to showing the likelihood of recurrence for purposes of

13 standing:

14 Moreover, where, as here, a plaintiff seeks prospective injunctive relief, he must

demonstrate "that he is realistically threatened by a repetition of [the violation]."

15 Lyons, 461 U.S. at 109 (emphasis added) (holding that plaintiff cannot establish the

16 requisite type of harm simply by pointing to some past injury). We review questions of

standing de novo. See Tyler v. Cuomo, 236 F.3d 1124, 1131 (9th Cir. 2000) (citation

17 omitted). However, we will affirm standing when a district court has made "explicit"

and "specific" findings establishing that the threatened injury is sufficiently likely to

18 occur, LaDuke, 762 F.2d at 1323-24; see also Hawkins, 251 F.3d at 1237 (citing

19 LaDuke), unless those findings are clearly erroneous.

20 There are at least two ways in which to demonstrate that such injury is likely

to recur. First, a plaintiff may show that the defendant had, at the time of the injury, a

21 written policy, and that the injury "stems from" that policy. Hawkins, 251 F.3d at

22 1237. In other words, where the harm alleged is directly traceable to a written policy,

see Gomez v. Vernon, 255 F.3d 1118, 1127 (9th Cir. 2001), there is an implicit

23 likelihood of its repetition in the immediate future. Second, the plaintiff may

demonstrate that the harm is part of a" pattern of officially sanctioned . . .

24 behavior, violative of the plaintiffs' [federal] rights." LaDuke v. Nelson, 762 F.2d

25 1318, 1323 (9th Cir. 1985). Id, (emphasis added).

26 In Armstrong, the district court specifically found that both the written policies and unwritten

27 practices of the defendant prison violated the rights of the disabled plaintiffs in that case. Thus, those

28 plaintiffs had standing to seek injunctive relief, and such injunctive relief was affirmed. 275 F.3d at

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 15

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 17 of 21

1 861-864.

2 In the present case, such federalism concerns are ameliorated where state law specifically

3 authorizes injunctive relief, and expressly finds that training of staff is appropriate prospective relief.

4 Cal. Gov't. C. § 12965(c). Here, Plaintiff does not have to establish his right to have this court invoke

5 general equitable relief over any remedies at law: he is specifically entitled to “injunctive relief” under

6 the state law on which he has prevailed. Furthermore, Plaintiff's harm was traceable to Defendant's

7 illegal policies. Moreover, the equitable relief that Plaintiff seeks will not require continuous

8 supervision by the federal court.

9 Fed.R.Civ. P. 65 codified the common law doctrines of irreparable harm and lack of adequate

10 remedy at law in injunction practice. Rule 65(b), which deals with preliminary injunctions, refers to

11 irreparable injury. But Rule 65(d), dealing with post-trial injunctions is void of any such language. This

12 makes good sense in that, after a trial or hearing on the merits, there is no need to show irreparable

13 injury to obtain temporary relief pending hearing or trial.

14 Indeed, where employment discrimination is concerned, the rule in this jurisdiction has long

15 been that no showing of irreparable harm is necessary even for preliminary injunctions, let alone those

16 arising after trial on the merits. In Middleton-Keirn v. Stone, 655 F.2d 609, 609 (5th Cir. 1981), the

17 court noted that irreparable injury is presumed in both public and private employment discrimination. In

18 another case, that same court held that when an injunction is specifically authorized by statute, the court

19 will dispense with the inquiry into irreparable harm. Murray v. American Standard, Inc., 488 F.2d 529,

20 531 (5th Cir. 1973). In United States v. Hayes International Corp., 415 F.2d 1038, 1045 (5th Cir. 1969),

21 the court found that the usual perquisites of irreparable injury need not be independently established if

22 unlawful employment discrimination is established.

23 Accordingly, in the case at hand, in the equitable remedy phase following a finding of

24 discrimination, the Court may rely simply on the express statutory authorization of Title VII as

25 conferring all the power necessary to order appropriate injunctive relief.

26 Like TVII, a primary purpose of the FEHA is to provide effective remedies that will prevent

27 future unlawful employment practices. Aguilar v. Avis Rent A Car (1999) 21 Cal.4th 121, 131. One such

28 remedy available under the FEHA is affirmative injunctive relief requiring employers to take proactive

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 16

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 18 of 21

1 steps to adhere to the equal employment opportunity laws, such as training and educating employees

2 concerning the scope of these laws and how to comply with or enforce them. Aguilar, supra, 21 Cal.4th

3 at 131 (FEHA plaintiff may obtain "[a]ffirmative or prospective relief to prevent the recurrence of the

4 unlawful practice"); see also Herr v. Nestle, USA, Inc. (2003) 109 Cal.App.4th 779, 789-790

5 ("[I]njunctive relief under the UCL is an appropriate remedy where a business has engaged in an

6 unlawful practice of discriminating against older workers.... Therefore, an employer which engages in

7 age discrimination in violation of the FEHA is subject to a prohibitory injunction under the UCL. For

8 these reasons, the trial court properly enjoined Nestle under the UCL from engaging in age

9 discrimination in violation of FEHA.").

10 Courts in California and throughout the country routinely issue injunctions such as that requested

11 here. See e.g., DFEH v. Lactalis USA, Inc. (2002) FEHC Dec. No. 02-15; 2002 WL 31520127, *14

12 (injunction requiring employer to train its employees and managers with respect to harassment policy

13 and "to implement a training program to inform its employees, supervisors, and managers fully of the

14 nature of the prohibited harassment, the duty of all employers, supervisor, and managers to prevent and

15 eliminate harassment in the workplace, and the procedures and remedies available under respondent’s

16 anti-harassment policy and state law."); Madera, supra, FEHC Dec. No. 90-03; 1990 WL 312871, *32

17 (injunction requiring employer to implement training program concerning workplace harassment rules);

18 DFEH v. Del Mar Avionics (1985) FEHC Dec. No. 85-19; 1985 WL 62898, *24 (injunction requiring,

19 inter alia, employer to implement a proper procedure for investigating workplace harassment allegations

20 and to conduct two annual training sessions of employees); Arnold v. City of Seminole (E.D. Okla. 1985)

21 614 F.Supp. 853 (injunction requiring employer to refrain from harassing behavior, notify all employees

22 and supervisors of the laws concerning harassment, develop a clear and effective procedure for resolving

23 harassment complaints, and develop appropriate sanctions and punishment for harassment); Bundy v.

24 Jackson (D.C. Cir. 1981) 641 F.2d 934, 947-948 (injunction requiring employer to establish "prompt

25 and effective procedure for hearing, adjudicating, and remedying complaints of sexual harassment

26 within the agency"). This case should be no different. The evidence at trial provides multiple bases for

27 this important request for injunctive relief.

28 The equitable relief favored by established law in employment discrimination is much broader

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 17

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 19 of 21

1 than in most other areas of law. Some of the principles governing such relief are unique or at least

2 uncommon. Many doctrines arose at a time when the principal remedial statute, Title VII, afforded only

3 equitable relief. Congress amended Title VII in 1991 to provide for damages within certain caps based

4 upon the number of the defendant’s employees, but as the Supreme Court just made clear once again in

5 Pollard v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 2001 WL 589077 (U.S. June 4, 2001), consistently over the

6 years, despite the many twists and turns that have accompanied the liability wing of discrimination law

7 the advent of damages did not in any sense prune back the equitable relief that was previously available.

8 Most of the doctrines guiding such relief developed early on and have been applied.

9 At the remedial stage, after a finding of liability, the Court should remedy any discrimination

10 brought to its attention. The insignificance of the injury is not a defense to relief. This is a useful

11 corollary to the make-whole doctrine. Our court of appeals established this principle in a case in which

12 the trial court found that a discriminatory transfer of one of the plaintiffs for a short period of time was

13 de minimis and not worthy of relief. The court of appeals reversed, stating:

14 We cannot accept this characterization. Title VII gives us no license to decide that any

injury, however insignificant, may be regarded as de minimis. As appellant argues,

15 “what is small in thprincipal is often large in principle . Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400

F.2d 28, 32-33 (5 Cir. 1968).”; Cox v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 784 F.2d 1546,

16 1561 (11th Cir. 1986).

17 Courts fashioning equitable remedies in Title VII cases have borrowed a key principle of general

18 equity law: once illegal conduct has been found, the presumption arises that injunctive relief should

19 issue unless the defendant can show strong reasons why it should not. Most jurisprudence in this aspect

20 of discrimination law has relied upon the landmark case United States v. W.T. Grant, 345 U.S. 629, 633

21 (1953). Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 442 U.S. 405, 418 (1975) (quoted above), incorporated this

22 principle wholesale into discrimination law.

23 Not only the plaintiff’s presumptive entitlement to injunctive relief, but the shifting of the burden

24 to the employer to prove by clear and convincing evidence (not just a preponderance) that the relief

25 should be denied, are well-settled in this jurisdiction. Perhaps the most cogent expression is the

26 following:

27 Once discrimination is proved, a presumption of entitlement to back pay and individual

injunctive relief arises. The burden of proof then shifts to the employer to show by clear

28 and convincing evidence that [injunctive relief should be denied]. McCormick v. Attala

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 18

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 20 of 21

1 County Board of Education, 541 F.2d 1094,1095th(5th Cir. 1976) (citations omitted);

accord, Lewis v. Smith, 731 F.2d 1535, 1538 (11 Cir. 1984); Nord v. U.S. Steel Corp.,

2 758 F.2d 1462,th1473 (11th Cir. 1985); Joshi v. Florida State Univ. Health Ctr., 763 F.2d

1227, 1236 (11 Cir. 1985).

3

4 The “clear and convincing evidence” standard cannot generally be met by mere cessation of the

5 discriminatory practice. It is abuse of discretion to deny injunctive relief on that basis: “reform timed to

6 anticipate or blunt the force of a lawsuit offers insufficient assurance that the practice sought to be

7 enjoined will not be repeated.” NAACP v. City of Evergreen, 693 F.2d 1367, 1370 (11th Cir. 1982)

8 (citing United States v. W.T. Grant, supra); accord, EEOC v. Alton Packaging Corp., 901 F.2d 920, 926

9 (11th Cir. 1990). Here, because Defendant's policies limit medical leave to 480 hours, reoccurrence of

10 the harm suffered by Plaintiff is inevitable.

11 Even systemic relief may arise from an individual case. Cary v. Greyhound Bus Co., 500 F.2d

12 1372 (5th Cir. 1974) (class certification not required for individual plaintiff to obtain broad injunctive

13 relief); Carmichael v. Birmingham Saw Works, 738 F.2d 1126 (11th Cir. 1984) (injunctive relief may

14 benefit individuals not party to suit and class-wide relief may be appropriate in an individual action).

15 The analysis of a leading scholar in the field concludes that such treatment flows from the Supreme

16 Court’s remedial jurisprudence in Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 442 U.S. 405 (1975), and Franks v.

17 Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976). See, Robert Belton, Remedies In Employment

18 Discrimination Law, Wiley 1992, § 6.11.

19 Training for supervisors and employees in equal opportunity obligations is a commonplace

20 equitable remedy in discrimination cases. See e.g., Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 11 EPD ¶ 10,692

21 at 6,900 (W.D. N.C. 1976), aff’d, 555 F.2d 1181 (4th Cir. 1977), modified on other grounds, 575 F.2d

22 471 (4th Cir. 1978), cert. den., 440 U.S. 979 (1979); Sims v. Montgomery County Commission, 766 F.

23 Supp. 1052 (M.D. Ala. 1991); Stair v. Lehigh Valley Carpenters, 855 F. Supp. 90 (E.D. Pa. 1994);

24 EEOC v. Murphy Motor Freight Lines, 488 F. Supp. 381 (D. Minn. 1980). This is a good example of an

25 area in which the relief of an individual plaintiff quite properly involves systemic reform.

26 The evidence at trial, as set forth in the proposed findings of fact, supra, established a need for

27 such training, and a change in Defendant's policy of restricting medical leave to 480 hours.

28 Enjoining retaliatory practices is strongly favored where there exists any substantial chance that

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 19

Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 390 Filed 06/19/2009 Page 21 of 21

1 such practices will occur in the future. EEOC v. Cosmair, Inc., 821 F.2d 1085 (5th Cir. 1987). It is also

2 necessary to give assurance to future complainants in a situation where the reasonable fear of reprisal is

3 so warranted by Defendant's retaliatory conduct towards a high profile employee such as Dr. Jadwin.

4 IV. MISCELLANEOUS RELIEF.

5 When final judgment is entered herein, Plaintiff hereby requests that the following provisions be

6 included:

7 1) The amount of economic damages awarded by the jury should be doubled on the grounds

8 that the jury found that Defendant's violations of FMLA was "willful" on both Plaintiff's

9 oppositional retaliation claim, and Plaintiff's retaliation claim for exercising his right to

10 medical leave, thus entitling Plaintiff to a mandatory award of liquidated damages. 29 USC

11 2617(a)(1)(A)(iii); Bachelder v. Am. W. Airlines, Inc., 259 F.3d 1112, 1130 (9th Cir. Ariz.

12 2001).

13 2) The award of pre-judgment and post-judgment interest. Discrimination plaintiffs are

14 presumptively entitled to pre-judgment interest on monetary recoveries. EEOC v. Guardian

15 Pools, Inc., 828 F. 2d 1507 (11th Cir. 1987). Post-judgment interest is mandated by Congress

16 at 28 U.S.C. § 1961. See generally, Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical Corp. v. Bonjorno, 494

17 U.S. 827 (1990).

18 3) The award of costs of litigation to Plaintiff as the prevailing party, according to proof per

19 Plaintiff's Bill of Costs due to be filed by June 27, 2009.

20 4) The award of attorney's fees to Plaintiff pursuant to Section 12965 of the Government Code

21 [FEHA/CFRA], 29 U.S.C. § 2617(a)(3) [FMLA], and if Plaintiff prevails on his due process

22 claim, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 according to proof pursuant to Plaintiff's Application for attorney's

23 fees due to be filed (presumably) by July 10, 2009.

24

RESPECTFULLY SUBMITTED on June 19, 2009.

25

26

By: __________/s/ Joan Herrington__________

27 Attorney for Plaintiff DAVID F. JADWIN

28

USDC, ED Case No. 1:07-cv-00026 OWW DLB

PLAINTIFF’S CLOSING BRIEF 20

Вам также может понравиться

- Case 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 324 Filed 05/01/2009 Page 1 of 39Документ39 страницCase 1:07-cv-00026-OWW-DLB Document 324 Filed 05/01/2009 Page 1 of 39Eugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 395 P Reply Bill of CostsДокумент16 страниц395 P Reply Bill of CostsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 325 P Trial BriefДокумент12 страниц325 P Trial BriefEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 134 Request For Reconsideration Re RPD1Документ101 страница134 Request For Reconsideration Re RPD1Eugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Nguyen v. AstrueДокумент13 страницNguyen v. AstrueNorthern District of California BlogОценок пока нет

- 315 Defendants Pretrial StatementДокумент18 страниц315 Defendants Pretrial StatementEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 318 Plaintiffs Supp PTC StatementДокумент80 страниц318 Plaintiffs Supp PTC StatementEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 293 P Opp - D MJOPДокумент127 страниц293 P Opp - D MJOPEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 282 D MSJ - Opp - SSДокумент115 страниц282 D MSJ - Opp - SSEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 348 P Prop JIДокумент127 страниц348 P Prop JIEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 236 P MX Amend SAC - P ReplyДокумент7 страниц236 P MX Amend SAC - P ReplyEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 311 Order MsjsДокумент141 страница311 Order MsjsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Filed & Entered: Clerk U.S. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California by Deputy ClerkДокумент10 страницFiled & Entered: Clerk U.S. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California by Deputy ClerkChapter 11 DocketsОценок пока нет

- 398 ORDER Bench TrialДокумент36 страниц398 ORDER Bench TrialEugene D. Lee100% (1)

- 68 DFJ Request For Reconsideration of Order Denying MTSДокумент42 страницы68 DFJ Request For Reconsideration of Order Denying MTSEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Plaintiff'S Reply To Defs.' Response To February 23, 2011 Order Case No. 3:10-cv-0257-JSW sf-2964618Документ5 страницPlaintiff'S Reply To Defs.' Response To February 23, 2011 Order Case No. 3:10-cv-0257-JSW sf-2964618Equality Case FilesОценок пока нет

- Filed & Entered: Clerk U.S. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California by Deputy ClerkДокумент9 страницFiled & Entered: Clerk U.S. Bankruptcy Court Central District of California by Deputy ClerkChapter 11 DocketsОценок пока нет

- 295 D Reply - D MJOPДокумент5 страниц295 D Reply - D MJOPEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Send To:: 117ZZW Citron, Michael Florida International University Law 11200 SW 8TH ST MIAMI, FL 33199-0001 19:18:20 ESTДокумент7 страницSend To:: 117ZZW Citron, Michael Florida International University Law 11200 SW 8TH ST MIAMI, FL 33199-0001 19:18:20 ESTabelawfirmОценок пока нет

- 163-1 P Ex Parte Shorten Time Re MTC DeposДокумент90 страниц163-1 P Ex Parte Shorten Time Re MTC DeposEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Order Granting Motion For Preliminary InjunctionДокумент13 страницOrder Granting Motion For Preliminary InjunctionSon Burnyoaz100% (1)

- Laurelwood FileДокумент19 страницLaurelwood Filethe kingfishОценок пока нет

- Vijay v. 20th Century Fox - Titanic Actor Decision Right of Publicity and LaborДокумент15 страницVijay v. 20th Century Fox - Titanic Actor Decision Right of Publicity and LaborMark JaffeОценок пока нет

- Hemsley V.mrs. Toni 1983Документ4 страницыHemsley V.mrs. Toni 1983Northern District of California BlogОценок пока нет

- 106 - Lisa Opposition To Motion For Default JudgmentДокумент15 страниц106 - Lisa Opposition To Motion For Default JudgmentRipoff ReportОценок пока нет

- Case 1:07 CV 00026 Oww DLBДокумент99 страницCase 1:07 CV 00026 Oww DLBEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Princeton/Aetna Vs Class ActionДокумент12 страницPrinceton/Aetna Vs Class ActionJakob EmersonОценок пока нет

- Queens Hospitality v. Breakfast Bitch - Motion To Dismiss (For, Inter Alia, No Complaint)Документ10 страницQueens Hospitality v. Breakfast Bitch - Motion To Dismiss (For, Inter Alia, No Complaint)Sarah BursteinОценок пока нет

- 20 08 12 Petition For ContemptДокумент39 страниц20 08 12 Petition For ContemptDanny ShapiroОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitДокумент13 страницUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Hutto, 10th Cir. (2006)Документ8 страницUnited States v. Hutto, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Brian Fox v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida Inc., 11th Cir. (2013)Документ7 страницBrian Fox v. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida Inc., 11th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Carlile v. Conoco, Inc., 10th Cir. (2001)Документ8 страницCarlile v. Conoco, Inc., 10th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Mikerin Plea DealДокумент13 страницMikerin Plea DealM Mali100% (5)

- Opposition To Motion To Dismiss - FILEDДокумент18 страницOpposition To Motion To Dismiss - FILEDVince4azОценок пока нет

- Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134 (1974)Документ75 страницArnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134 (1974)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Biden Opposition To Motion For Leave To AmendДокумент9 страницBiden Opposition To Motion For Leave To AmendDavid FoleyОценок пока нет

- 29 Scheduling OrderДокумент19 страниц29 Scheduling OrderEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- Judge Bunning RulingДокумент20 страницJudge Bunning RulingWCPO 9 NewsОценок пока нет

- Filing in Former Police Chief Acevedo's Federal LawsuitДокумент24 страницыFiling in Former Police Chief Acevedo's Federal LawsuitAndreaTorresОценок пока нет

- Marquez v. Wilson 1983 MSJДокумент6 страницMarquez v. Wilson 1983 MSJNorthern District of California BlogОценок пока нет

- Minton v. Deloitte and Touche USA LLP Plan ERISA MSJДокумент13 страницMinton v. Deloitte and Touche USA LLP Plan ERISA MSJNorthern District of California BlogОценок пока нет

- USCOURTS Utd 2 - 17 CV 00563 0 PDFДокумент11 страницUSCOURTS Utd 2 - 17 CV 00563 0 PDFTriton007Оценок пока нет

- 103 - Request For Judicial NoticeДокумент6 страниц103 - Request For Judicial NoticeRipoff ReportОценок пока нет

- Filed: Patrick FisherДокумент8 страницFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Williams v. Jones, 11 F.3d 247, 1st Cir. (1993)Документ17 страницWilliams v. Jones, 11 F.3d 247, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Perry v. New England Business, 347 F.3d 343, 1st Cir. (2003)Документ5 страницPerry v. New England Business, 347 F.3d 343, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Fred Marvel and Angela Marvel, Dba Marvel Photo v. United States, 548 F.2d 295, 10th Cir. (1977)Документ8 страницFred Marvel and Angela Marvel, Dba Marvel Photo v. United States, 548 F.2d 295, 10th Cir. (1977)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Charlie Lee Blake v. Union Camp International Paper, 11th Cir. (2015)Документ6 страницCharlie Lee Blake v. Union Camp International Paper, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- David A. Lampe v. Xouth, Inc., Phillippe G. Woog, 952 F.2d 697, 3rd Cir. (1992)Документ6 страницDavid A. Lampe v. Xouth, Inc., Phillippe G. Woog, 952 F.2d 697, 3rd Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Gagnon v. Resource Technology, 10th Cir. (2001)Документ11 страницGagnon v. Resource Technology, 10th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Oposición de Justicia FederalДокумент11 страницOposición de Justicia FederalEl Nuevo DíaОценок пока нет

- Anthony Yemoh Smith v. TIGTAДокумент6 страницAnthony Yemoh Smith v. TIGTAJudicial Watch, Inc.Оценок пока нет

- 102 - Motion To DismissДокумент17 страниц102 - Motion To DismissRipoff ReportОценок пока нет

- Petition Non-Ibr Dispute ModifiedДокумент3 страницыPetition Non-Ibr Dispute ModifiedMichael Blott100% (1)

- Baker Botts Motion For Anti-Slaap Attorney Fees After Notice of Dismissal July 16 2020Документ6 страницBaker Botts Motion For Anti-Slaap Attorney Fees After Notice of Dismissal July 16 2020Teri BuhlОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionОт EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionОценок пока нет

- Construction Liens for the Pacific Northwest Alaska Idaho Oregon Washington Federal Public Works: A PrimerОт EverandConstruction Liens for the Pacific Northwest Alaska Idaho Oregon Washington Federal Public Works: A PrimerОценок пока нет

- A Guide to District Court Civil Forms in the State of HawaiiОт EverandA Guide to District Court Civil Forms in the State of HawaiiОценок пока нет

- 309 Proposed Order Re Revised Scheduling OrderДокумент1 страница309 Proposed Order Re Revised Scheduling OrderEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 398 ORDER Bench TrialДокумент36 страниц398 ORDER Bench TrialEugene D. Lee100% (1)

- Live 3.2.2 CM/ECF - U.S. District Court For Eastern CaliforniaДокумент36 страницLive 3.2.2 CM/ECF - U.S. District Court For Eastern CaliforniaEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 332 P Notice Lodging TX-DiscoДокумент3 страницы332 P Notice Lodging TX-DiscoEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 396 Order P MilsДокумент8 страниц396 Order P MilsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 392 P Bill of CostsДокумент247 страниц392 P Bill of CostsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 394 D Obj Bill of CostsДокумент12 страниц394 D Obj Bill of CostsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 387 Trial Exh Witn ListsДокумент7 страниц387 Trial Exh Witn ListsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 391 D Closing BriefДокумент11 страниц391 D Closing BriefEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 384 Jury VerdictДокумент30 страниц384 Jury VerdictEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 340 Joint Trial ExhibitsДокумент35 страниц340 Joint Trial ExhibitsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 386 Jury InstructionsДокумент33 страницы386 Jury InstructionsEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- 348 P Prop JIДокумент127 страниц348 P Prop JIEugene D. LeeОценок пока нет

- ADR NotesДокумент8 страницADR NotesAngela ParadoОценок пока нет

- Civil Law DoctrinesДокумент21 страницаCivil Law DoctrinesAngela B. LumabasОценок пока нет

- Admin Law Exam NotesДокумент126 страницAdmin Law Exam Notespappas69Оценок пока нет

- Occena v. ComelecДокумент7 страницOccena v. ComelecGC M PadillaОценок пока нет

- Virsa Singh v. State of PunjabДокумент5 страницVirsa Singh v. State of PunjabVijay VaghelaОценок пока нет

- 3-Mamiscal Vs AbdullahДокумент26 страниц3-Mamiscal Vs AbdullahSugar Fructose GalactoseОценок пока нет

- 2928Документ122 страницы2928MohammedThabrezОценок пока нет

- Midterm SampleДокумент8 страницMidterm SampleLevz LaVictoriaОценок пока нет

- PEDG-EDLD 5344 Week 4 AssignmentДокумент7 страницPEDG-EDLD 5344 Week 4 Assignmentsnshn643Оценок пока нет

- 9 6 13 0204 62337 NVD Stamped 13 CV 474 RCJ WGC 664 Pages IFP MTN Proposed Complaint Coughlin V Wal-Mart, Reno Sparks Indian Colony, RSIC OptДокумент664 страницы9 6 13 0204 62337 NVD Stamped 13 CV 474 RCJ WGC 664 Pages IFP MTN Proposed Complaint Coughlin V Wal-Mart, Reno Sparks Indian Colony, RSIC OptNevadaGadflyОценок пока нет

- Armando Yrasuegui Vs PAL G.R. No. 168081Документ6 страницArmando Yrasuegui Vs PAL G.R. No. 168081Christian Jade HensonОценок пока нет

- Cert. of ExpensesДокумент1 страницаCert. of ExpensesVictor Dagohoy DumaguitОценок пока нет

- Republic Vs Sagun PDFДокумент16 страницRepublic Vs Sagun PDFMarc Dave AlcardeОценок пока нет

- CPD InternalAffairsReport 2015Документ44 страницыCPD InternalAffairsReport 2015WACHОценок пока нет

- United States v. Riesterer, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Riesterer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Ravina v. Villa Abrille, GR 160708Документ8 страницRavina v. Villa Abrille, GR 160708Anna NicerioОценок пока нет

- ABS-CBN v. CA - DigestДокумент2 страницыABS-CBN v. CA - DigestJilliane Oria100% (3)

- Sample Deed NovationДокумент7 страницSample Deed NovationFatima PascuaОценок пока нет

- R 35 Memo For The RespondantДокумент25 страницR 35 Memo For The RespondantabhishekОценок пока нет

- Section 8 of Evidence ActДокумент17 страницSection 8 of Evidence ActashishОценок пока нет

- Domicile of Corporations and Pseudo CorporationsДокумент20 страницDomicile of Corporations and Pseudo CorporationsAnkur Gupta50% (2)

- Cross CulturalДокумент11 страницCross CulturalPing Tengco LopezОценок пока нет

- NDA Draft General-1Документ7 страницNDA Draft General-1Adi TОценок пока нет

- Jeff Epstein Notes PDFДокумент2 страницыJeff Epstein Notes PDFAnonymous SjL2rOwHan73% (11)

- Relationships For Incarcerated IndividualsДокумент11 страницRelationships For Incarcerated IndividualsDavidNewmanОценок пока нет

- Concept of Muslim MarriageДокумент7 страницConcept of Muslim MarriageLMRP2 LMRP2Оценок пока нет

- Individualism and Collectivism ContentДокумент7 страницIndividualism and Collectivism ContentNguyễn Ngọc Minh AnhОценок пока нет

- A Theory of Justice by John Rawls PDFДокумент15 страницA Theory of Justice by John Rawls PDFHarsh DixitОценок пока нет

- FSC-POL-01-004 V2-0 en Policy For AssociationДокумент6 страницFSC-POL-01-004 V2-0 en Policy For AssociationDaniel ModicaОценок пока нет

- VOCA BrochureДокумент2 страницыVOCA BrochureCFRC LafayetteОценок пока нет