Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

F1 Wealth Creation

Загружено:

FormulaMoneyАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

F1 Wealth Creation

Загружено:

FormulaMoneyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

68 FALL 2013

No. 1 / THE SPORT

WORDS Caroline Reid

ILLUSTRATION Paul Laguette/iStock

For more than three decades, Bernie Ecclestone has been relentlessly focused and hugely successful in his quest to turn Formula 1 into a multi-billion dollar commercial colossus.

ts no secret that Bernie Ecclestone is responsible for Formula 1s scale and reach as a truly global sport. But the extent of his impact is only apparent when comparing the F1 of today with how it was before the 83-year-old billionaire recognized and nurtured its vast, underexploited potential. Four decades ago, F1 was a shadow of what it is today. It was a disparate collection of tracks with often lamentable safety standards, a freewheeling circus of teams and drivers that rarely acted in unison, and piecemeal TV that made it a challenge to follow for all but the most ardent fan. Sure, it had Ferrari, Monaco and Jackie Stewart, but it was an adrenaline-fueled spectacle despite itself. One savvy opportunist saw the potential, however, and his transformation from team owner to an exponentially

increasing role as organizer, agitator and catalyst for change forged the modern F1. Ecclestone bought the Brabham team at the end of 1971 and enjoyed a certain level of success, culminating in F1 Drivers World Championships for Nelson Piquet in 1981 and 83. However, the Englishman always had an eye on the bigger picture: TV. Into the heart of the 1970s, teams still made separate deals with event promoters, and event promoters mostly made whatever deal they could with a local TV network. Ecclestone made inroads into organizing teams to deal with promoters as a single entity and formalizing TV deals when possible. But the dening moment came in 1981 when, after a period of conict with F1s governing body, the FIA, he persuaded the teams to sign a contract, the Concorde

Agreement, that commited them to appear in every grand prix. The agreement also granted FOCA, the teams association headed by Ecclestone, the TV rights to F1. With a guaranteed grid and the broadcast rights now leased to his own company, Formula One Promotions and Administration (FOPA), Ecclestone held all the aces. FOPA negotiated the deals and took a share of the proceeds, with the rest going to the teams and the governing body, the FIA. In 1982, he signed a three-year deal with the

F1 was an adrenaline-fueled spectacle despite itself. One savvy opportunist saw the potential, however

European Broadcasting Union which would ensure consistent coverage in F1s biggest markets in Europe. At last, the pieces of the puzzle were in place. With guaranteed TV, sponsor rates rocketed and teams morphed into the high-tech powerhouses they are today. At the same time, drivers like Alain Prost, Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell became household names to further fuel F1s superheated growth spurt. In 1990 FOPA had revenues of just $14.6m, but by 1995 this had ballooned to $129.7m and Ecclestones salary of $85.1m made him the worlds highestpaid executive. He still wasnt satised. He had turned 65 and suffered from heart problems which culminated in him having a triple bypass in 1999. The outlook was far from clear and Ecclestone wanted to leave a signicant nancial legacy for his

RACER.com 69

(RIGHT) Aged 83, F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone continues to be the prime mover in pushing the multi-billion dollar business forward. (LEFT) Ecclestones astute business savvy not only grew the sport, but made fortunes for many of his contemporaries.

Alastair Staley/LAT

Charles Coates/LAT

now ex-wife Slavica, who he had married in 1985, and their two young children. Ecclestones initial idea was to oat FOPA, but he was told this would be tough since it did not directly own the commercial rights to F1. They are ultimately owned by the FIA, which had granted them to the teams, who let FOPA manage them. To swerve around this, the FIA transferred to Ecclestones personal investment vehicle, FOCA Administration (now Formula One Management), the commercial rights to

F1 for 14 years beginning Jan. 1, 1997. Incredibly, in 2001, a new deal added another 100 years to the agreement, giving a new expiration date of Dec. 31, 2110. Ecclestone owned 100 percent of FOCA Administration, giving him complete control of F1s rights for the rst time in history. In return, the FIA received a paltry annual sum of $10.3m. In 1997 alone, FOCA Administration made a net prot of $90.7m, giving Ecclestone an annual return on investment of more than 900 percent.

(ABOVE) TV rights were the catalyst that set F1 on teh nancial fast track in the early 1980s and they remain key today. (ABOVE RIGHT) The 72 season was Bernie Ecclestones rst year as an F1 team owner, helming Brabham.

eUroPeaN EXIT

When Bernie Ecclestone rolled out the original 1981 Concorde Agreement, the document that denes Formula 1s commercial protocols, 10 of 15 grands prix were based in Europe. In 2013, just seven of the 19 races were located in F1s old heartland, with non-traditional markets now dominating.

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5

KEY: EUROPEAN

NON EUROPEAN

USA

70 FALL 2013

1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

YEAR

The best business move of his career had handed him the keys to the billionaires club. Since then, Ecclestone has made $3.9bn from selling stakes in the company and taking out loans secured on its revenues. Despite the company changing hands repeatedly, hes managed to stay in the driving seat. Crucially, he also ensured that F1s main revenue streams stayed within the company. Many major sports let venues arrange the advertising and corporate hospitality during their events, but not F1. The latest nancial statements for F1s parent company Delta Topco are for the year-ending Dec. 31, 2011 and show revenues of $1.5bn. This generally comes from four main sources (see table, page 72). Trackside advertising at each race and series sponsorship comprises 15 percent of the total revenue. This comes from companies such as the Emirates airline and watch manufacturer Rolex, which are two of F1s ofcial partners. Corporate hospitality, freight fees and revenues from the GP2 and GP3 support series add around 20 percent of the total. Fees from F1s 63 TV contracts bring in 32 percent of the revenue and are second only to the money received from the races on the calendar. Together, the race hosting fees comprise 33 percent of the total, adding up to $512m in 2011. Just ve years earlier, the revenue from race hosting fees only came to $304m. But its been boosted by more than $200m, thanks to a bidding war for the prized slots on F1s calendar. For many countries, holding an F1 race

NUMber of raCeS

LAT archive

No. 1 / THE SPORT

PUTTING ON THE SHOW

Neither is cheap, but how do F1 road and street track costs compare?

Unlike most other major sports, F1 race promoters dont generally get to keep any of the revenue from trackside advertising or corporate hospitality. Neither do they get a share of revenue from TV broadcasting. A race promoters primary source of income from a grand prix is usually ticket sales, and this typically barely covers the hosting fee paid to the Formula One Group. According to F1s industry monitor Formula Money, national or local governments invest almost $450m in races every year. On average, ticket sales comprise $22m of the $27m average revenue for permanent circuits and $29.5m of the $32.5m brought in by street races. With hugely popular races such as Singapore and Australia, street circuits attract a higher average attendance. Venues get around 25 percent commission on food and drink sold at track outlets. This brings in around $1m, while premium parking makes around half that. Less obvious is that helicopter take-off and landing slots at permanent tracks can bring in $1.5m. The world record for most commercial aircraft movements in a single day is Silverstones heliport during the 1999 British Grand Prix, with 4,200. It now averages 1,500 per race, with each slot charged at approximately $1,000. Race costs differ signicantly between permanent and street tracks, with the latter more costly to organize. The biggest cost is the hosting fee, averaging around $27m for both track types. However, street tracks average $8m to rent portable pit buildings, another $8m for safety fencing and barriers and $14m on grandstand rentals. This gives permanent circuits total race costs estimated at $48m, whereas street races pay $87.5m on average. It leaves permanent venues with an annual decit of $21m, with street races losing $55m. Singapores government invested $66.9m in its race last year, but the latest trend comes from the U.S., where Texas has an innovative scheme which could mitigate much of the risk for governments investing in a grand prix. The state is investing up to $25m annually in the U.S. Grand Prix at Austins Circuit of The Americas via a fund which makes a payment to the race promoters based on the amount of tax income generated by spending as a result of the race.

PERMANENT CIRCUIT vs. street circuit

Ticket sales Other revenues TOTAL Costs LOSS BEFORE GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT

$22m $5m $27m -$48m -$21m

$27m $2.5m $29.5m -$87.5m -$55m

Source: Formula Money

Singapore is a popular F1 venue and a terric advert for the Southeast Asian city state, but government funding is a must.

RACER.com 71

Getty Images/Red Bull Content Pool

(LEFT) Ferrari and McLaren are two of F1s marquee brands and thats reected in the prize and bonus money they receive. (BELOW) Bernie Ecclestone with FIA president Jean Todt.

REVENUE Streams

Heres a breakdown of where F1s revenue came from in 2011, the most recent year where full accounts are available. Race hosting fees top the list. Source: Formula Money Race hosting fees $512m Television rights $489m Trackside ads and sponsorship $222m Corporate hospitality $80m Feeder series $55m Other sources $164m TOTAL REVENUE $1.5bn COSTS $350m Team prize money $698.5m UNDERLYING PROFIT $474m

Steve Etherington/LAT

FIA FLIES HIGHER WITH 13 CONCORDE

After years of receiving little more than pocket change, relatively speaking, in return for handing over the commercial rights to Formula 1, the FIA is set to nally receive some meaningful payback. The UKs Times newspaper says that racings governing body received $5m for signing the latest Concorde Agreement, with $200m more due during its eight-year life. A share in revenue if and when F1 is publicly oated is also said to be on the table. The new deal is a considerable improvement over the $10.3m per year the FIA previously received from F1.

is part global coming-of-age statement, part tourism driver, played out in front of a massive TV audience. Last year F1 attracted more than 500m TV viewers, making it the worlds most-watched annual sporting series (the Olympics and soccers World Cup are bigger, but on a quadrennial basis). In recent years, emerging economic powerhouses like Abu Dhabi and Singapore have woken up to the promotional power of F1, while superpower candidates such as China, India and for 2014 Russia view a grand prix as an obligatory status symbol. Central or regional governments are prepared to bankroll or underwrite the hosting fees for several of the new races, fueling a grand prix arms race and driving

Most of F1s key contracts contain clauses which increase fees paid by up to 10 percent annually

up hosting fees by $15.7m per event since 2003. The average fee was $27m in 2011, pricing many countries out of the running. Its a particular problem in F1s traditional European heartland, where F1 isnt needed to boost tourism, or governments are loathe to subsidize such agrant shows of conspicuous consumption. In the past ve years, Eurozone races have been lost in France, Germany, Spain and Turkey. Making matters harder for self-nancing grands prix, most of F1s key contracts contain clauses which increase fees paid

by up to 10 percent annually. This goes a long way to explain why F1 is one of the few industries (and it is an industry) with consistently rising revenue over the past ve years. It took in $1.07bn in 2006, rising to $1.16bn in 07. Since 08, when revenue hit $1.39bn, its increased at a compound annual growth rate of 3.1 percent. F1 doesnt own any tracks, so its costs are kept under tight control. It only has 313 staff and its biggest single cost is the payment of prize money to the teams (see page 74). The bulk of it is 47.5 percent of F1s prots remaining after all xed costs have been paid. Its split into two equal amounts, with one half divided equally between the top 10 teams and the other paid out based on nal points. Heritage payments to Ferrari and a Constructors Championship Bonus (CCB) divided between

Red Bull Racing, Ferrari and McLaren further add to the earnings of F1s big dogs. Giving the top teams the richest rewards may seem like a bad idea because it means that the same teams are the most likely to win. However, it helps secure F1s future. In a sport where teams enter and exit on a frequent basis, or change identity almost at will, Ferrari, McLaren and, latterly, Red Bull are marquee names, beacons of stability, and successful, too. In total, the 2011 prize money came to $698.5m. Although its F1s biggest cost, being a prot share links it directly to nancial performance. The more money F1 makes, the more the teams get. In 2011, that left F1 with a $474m prot, and a great deal of media attention has been given to how private equity rm CVC Capital Partners beneted from this. Last year alone, CVC netted $2.1bn through selling 28.4 percent of F1 to three investment companies. That left it with 35.5 percent, keeping it as the biggest single shareholder. In addition, it has received hundreds of millions of dollars in dividends from F1s prots. However, CVC has been far from the only beneciary. Prize money rose by $450.5m in just the four years to 2011, and since CVC bought F1 in 2006, the teams have banked more than $3.7bn. Even if you include the income from the share sales, the sum that CVC has received from F1 is roughly similar to the amount received by the teams. It makes Bernie Ecclestones current $3.9m salary seem small in comparison, but such is the gargantuan scale of F1s nances.

72 FALL 2013

Charles Coates/LAT

TV TIME EQUALS DOLLARS

When it comes to the all-important TV exposure that ensures manufacturers and sponsors are getting value for their investment, Formula 1 is an unforgiving meritocracy. Teams racing for the top positions get more screen time, which makes them more attractive propositions to sponsors than the guys at the back.

WORDS Caroline Reid

MAIN imaGE Andy Hone/LAT

74

FALL 2013

No. 2 / THE TEAMS

ORGANIZATIONS

If you think Formula 1 teams make huge prots, think again. Just about every last cent is spent in the pursuit of victory.

his year, the 11 teams in the Formula 1 World Championship will take over $2bn in revenue. Its a remarkable amount to generate from 22 drivers racing around a track for a couple of hours 19 times a season. However, although the teams receive those vast sums of money, they will nish the year with next to no prot. Welcome to the weird world of F1 nance. Generally, F1 teams are run to break even. This involves the team principals spending whatever is available to them, and they do it in the single-minded pursuit of victory. The established theory is that its better to race for wins and championships and make no prot, rather than make money and nish low down the standings.

BUILDING VALUE

Simply, winning races increases the value of the team which gives the owners a future payout if and when they come to sell it. It also increases the teams ability to bring in more money from sponsorship, since brands are prepared to pay more to be associated with a winning team. But while team owners may get a nancial return from selling a team in the long run, whats in it for them in the short term?

If the team is owned by a private individual, such as Sir Frank Williams, who has a 50.8 percent stake in his eponymous team, they can take an annual salary. This comes out as a cost to the team just like salaries paid to staff. Eight F1 teams are based in the UK and therefore have to le publicly available nancial statements. The most recent year for which a complete set is available is 2011, and this reveals that the team with the highest-paid director was Red Bull Racing. Its team principal is Christian Horner, and hes believed to have received the sum of $2m (1.3m) shown on the nancial statements. If the owner is an auto maker like Mercedes, or a commercial concern such as Red Bull, the benet they get while the team runs to break-even comes from TV and media exposure of their brand as logos on the cars and drivers. According to F1s trade guide Formula Money, Red Bull was the most exposed brand in F1 for the past three years. Its Advertising Value Equivalent (AVE) the price to buy a similar amount of on-screen exposure was an estimated $414.9m in 2011. That fell to $322.8m last year, due to Sebastian Vettel winning fewer races, but was still 14.2 percent of the total for all teams.

Sebastian Vettels nine wins from the rst 15 grands prix of 2013 gave Red Bull some serious TV exposure. But the correlation between winning and screen time isnt always clear cut win too easily and the directors going to linger on the brawls behind you...

PAYING TO BE SEEN

In 2011, the accounts show that F1s UK-based teams had average revenues of $150.8m (97.6m), with Red Bull highest at a staggering $273.2m (176.8m) and Caterham lowest at just $33.2m (21.5m). The teams revenue generally comes from three sources, with each providing a similar amount. They are all fueled by

RACER.com 75

Alastair Staley/LAT

Heres what it costs to put your logo on some prime Formula 1 real estate the bodywork of a front-running team such as McLaren for a season (estimates are for both cars). Source: Formula Money

REAR WING/ENGINE COVER/SIDEPODS (LARGE LOGO)

$25M FOR EACH

Glenn Dunbar/LAT

REAR WING ENDPLATES (MEDIUM LOGO)

$5M

LOWER SIDEPOD (SMALL LOGO)

$1M

F1s huge television audience, which was estimated at slightly more than 500m viewers last year. The rst key revenue source is sponsorship and in this eld money certainly talks. The greater the potential exposure, the higher the cost. Generally speaking, the rear wing, engine cover and sidepods are the prime logo positions, and a sponsorship deal with a top team involving any one of these locations is likely to cost around $25m. At the lower end of the spectrum, small logos placed on the cockpit sides or

nose of the car can generally be purchased for less than $3m with a front-running team. Bearing in mind that these are annual gures, the total cost of the deal can be much greater as partnerships last for around three years on average. In the vast majority of cases, a teams marketing department secures the sponsorship, but occasionally it is brought onboard by a driver. Lower ranking teams sometimes take drivers purely on the understanding that companies they have connections with will provide sponsorship.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND 1

SUPPLY AND DEMAND 2

These are F1s aptly-named pay drivers and, even if they fall well short of a Vettel or Fernando Alonso in terms of pure talent, the money they bring to a team can often make up for it, since it can be used to push forward development of the car itself. Some sponsors dont even get presence on the cars and are instead known as suppliers. This is a cheaper alternative, and often doesnt involve a cash cost. Instead, a company provides equipment or services and, although they dont get TV exposure, usually receives many of the perks which come with on-car sponsorships passes into F1s exclusive paddock, use of the team logo in advertising and sometimes even driver appearances at company functions. Formula Moneys data shows that around 42 percent of team revenue comes from team-sourced sponsorship, with another major source being investment from team-owning companies at 24 percent, but the marketing benet from AVE compensates for this investment.

NEW ENGINE RULES ADD TO TEAM COSTS

The new-for-2014 Formula 1 engines could double the cost of supply for non-factory teams. Radical 1.6-liter, turbocharged V6 units with advanced energy recovery systems will replace the naturallyaspirated, 2.4-liter V8s used since 06. A single-season, two-car supply is now in the region of $13m, but is predicted to hit $25-$30m in 2014. The manufacturers say costs will fall dramatically in subsequent years.

Lorenzo Bellanca/LAT

Steven Tee/LAT

Ferraris Fernando Alonso is said to be on an annual retainer of $40m, a gure comparable with the highest-earning NFL quarterbacks.

76 FALL 2013

Based on accounts submitted, Red Bull Racing team principal Christian Horner is believed to have earned $2m in 2011.

The other major source of revenue comes from the teams prot share with F1.

Mercedes

POINTS MEAN PRIZES

No. 2 / THE TEAMS

CASE STUDY

MERCEDES GRAND PRIX

WING MIRRORS (SMALL LOGO)

Mercedes Formula 1 activities are split into two: Mercedes Grand Prix (race operation) and High Performance Engines (supplying McLaren and Force India, as well as its own race team) are separate entities. However, HPE cannot be isolated; nor can MGPs engineering satellite operating from Daimlers Stuttgart base. Combined, Mercedes has by far the largest spend in F1, with commensurate headcounts. These are offset (marginally) by the engine supply contracts with Force India and McLaren, the latter expiring after 2014 when it switches to the returning Honda. Williams will also join Mercedes customer ranks next season, when the new F1 engine formula come into play. These activities explain top-heavy structures, with recent intensive staff recruitment drives pointing to a ramping up of activities and corresponding budget increases. Mercedes GP is nanced by a combination of Daimler funding, sponsorship (the largest being the Malaysian national petro-chemical company Petronas), customer activities and FOM payments. Shareholding was diluted recently through an allocation to motorsport director Toto Wolff (30 percent) and non-executive chairman Niki Lauda (10 percent). Although a member of F1s Strategic Committee, the Mercedes GP operation is not a full member of the CCB, qualifying for annual incremental payouts of 8m until 2015, which from then on increases to 10m.

INCOME BREAKDOWN

$5M

SIDE OF TUB (MEDIUM LOGO)

$10M

TOP OF NOSE (SMALL LOGO)

$3M

(LEFT) On average, around 42 percent of a Formula 1 outts budget comes from team-sourced sponsorship. (BELOW LEFT) Ferrari has been part of the F1 World Championship since its inception in 1950. Its special payments from the sports annual prots reect that history and the marques massive fan appeal.

Under the long-in-the-making 2013 version of the Concorde Agreement the contract that binds together the FIA, the teams and the commercial rights holder, Formula 1 Group the teams are set to receive a total of 63 percent of the sports annual prots as prize money (compared with 50 percent in the previous Concorde Agreement that lapsed at the end of 2012). Under the previous Concorde Agreement, that comprised around 29 percent of total team revenue and came to the not inconsiderable sum of $698.5m in 2011, according to F1s most recent nancial statements. What you receive from the prot share isnt just based on your most recent on-track performances. Taking multiseason achievements into account, three

teams Red Bull Racing, Ferrari and McLaren receive varying Constructors Championship Bonus (CCB) payouts which add up to whatever is the greater of 7.5 percent of total prots or $100m. Based on its historic status and the importance of the Prancing Horse to F1, Ferrari receives an additional payout. Under the old agreement that was 2.5 percent, rising to 5 percent in the latest version. In real terms, winning the constructors title in 2012 gave Red Bull Racing an estimated $87m from the prize money pot. The remaining 5 percent of F1 team income comes from miscellaneous sources, such as the previously mentioned pay drivers, who typically bring $10m each to drive. The other drivers are paid to drive, and this averages at $5.2m per driver, rising to an estimated $40m for Ferraris Alonso. Drivers aside, after manufacturing and R&D, staff salaries are the second biggest cost for F1 teams, averaging $42.5m per outt, thanks to 600-plus staff numbers at the bigger teams. Its a huge gure, but its just one more example of how F1 teams manage to spend almost every dollar they receive in the relentless pursuit of victory.

LAT archive

2013 estimated spend and income: Spend: $256m (inc. engines) Income: $240m 33.33% ($80M) DAIMLER 40% ($96M) SPONSORS 26.67% ($64M) FOM EARNINGS FROM 2012

RACER.com 77

Alastair Staley/LAT

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- EuroBusiness - Billion-Dollar CircusДокумент5 страницEuroBusiness - Billion-Dollar CircusFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Metro - A New Big Bang TheoryДокумент1 страницаMetro - A New Big Bang TheoryFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- The Business of F1 ReportДокумент2 страницыThe Business of F1 ReportFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Rollercoaster ReturnsДокумент4 страницыRollercoaster ReturnsFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- ZOOM 2017 GalleryДокумент1 страницаZOOM 2017 GalleryFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- The Chequered List of Companies Sky News Has Linked To Investments in F1Документ1 страницаThe Chequered List of Companies Sky News Has Linked To Investments in F1FormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Monaco E-Mail OfferДокумент3 страницыMonaco E-Mail OfferFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Starwood Website BP BookingДокумент5 страницStarwood Website BP BookingFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- UPDATED Hotel Website OfferДокумент3 страницыUPDATED Hotel Website OfferFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Media Kit: The Business of F1Документ7 страницMedia Kit: The Business of F1FormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Hotel Website OfferДокумент3 страницыHotel Website OfferFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Tom Maley PresentationДокумент4 страницыTom Maley PresentationFormulaMoneyОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Physical Fitness - Midterm CoverageДокумент21 страницаPhysical Fitness - Midterm CoverageFasra ChiongОценок пока нет

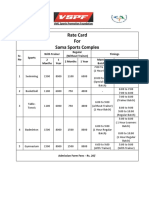

- VSPF Rate Card - Sama Sports ComplexДокумент1 страницаVSPF Rate Card - Sama Sports ComplexJAGDISHОценок пока нет

- Piper PA-34-200T Seneca II Manual PDFДокумент23 страницыPiper PA-34-200T Seneca II Manual PDFMuhammad Naveed0% (1)

- What To Do in Bosnia HerzegovinaДокумент1 страницаWhat To Do in Bosnia HerzegovinaDenis KajicОценок пока нет

- ParighasanaДокумент9 страницParighasanaLomombОценок пока нет

- Bolero Neo - E-Brochure - NewДокумент11 страницBolero Neo - E-Brochure - Newvaradha rajanОценок пока нет

- Nce Upon A Time, in The Quaint Village of LumariaДокумент1 страницаNce Upon A Time, in The Quaint Village of LumariaAdamu KassieОценок пока нет

- Crypts of RavenloftДокумент17 страницCrypts of Ravenloftevandro souza0% (2)

- Mossberg 2016 CatalogДокумент88 страницMossberg 2016 CatalogMario Lopez100% (2)

- Doctor Who AITAS Limited EditionДокумент256 страницDoctor Who AITAS Limited Editionherzog100% (1)

- Passage 6Документ2 страницыPassage 6Yến ChiОценок пока нет

- Eye of Abyss Item CardsДокумент5 страницEye of Abyss Item CardsmhamlingОценок пока нет

- Dumbbell DisorderДокумент13 страницDumbbell Disordercstolvr100% (2)

- Armada: From The Author of READY PLAYER ONE - Ernest ClineДокумент6 страницArmada: From The Author of READY PLAYER ONE - Ernest Clinenafizemy33% (3)

- Fastner and Tooling Components. Fertrading Group Venezuela.Документ4 страницыFastner and Tooling Components. Fertrading Group Venezuela.Renso PiovesanОценок пока нет

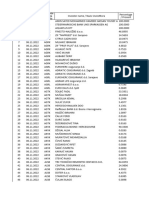

- NEw DataДокумент8 страницNEw DataDeepak GoyalОценок пока нет

- Yamaha Yzf r15 Version 2-0-2015 User ManualДокумент62 страницыYamaha Yzf r15 Version 2-0-2015 User ManualAswin Lovez Candy's100% (1)

- 20210720-20210720 SweetBet88Документ320 страниц20210720-20210720 SweetBet88Andrei RosiulescuОценок пока нет

- ACDC - Hard As A RockДокумент2 страницыACDC - Hard As A RockJazz QuevedoОценок пока нет

- Top 10 Cable HM 25-44 ABCДокумент3 страницыTop 10 Cable HM 25-44 ABCVeronica ArteagaОценок пока нет

- Organization and Management of Sports EventДокумент4 страницыOrganization and Management of Sports EventErnan GuevarraОценок пока нет

- Terrain and BuildingДокумент9 страницTerrain and BuildingAde MarkusОценок пока нет

- Masa Kanak Kanak AkhirДокумент64 страницыMasa Kanak Kanak AkhirTofanОценок пока нет

- Rules of The Game Kho KhoДокумент3 страницыRules of The Game Kho KhoHoney Ali50% (2)

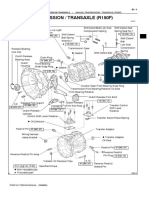

- Manual Transmission (R150F)Документ3 страницыManual Transmission (R150F)daniel_gustavo_2002100% (4)

- Manny 2Документ2 страницыManny 2unicronicОценок пока нет

- Arnis A Filipino Martial ArtДокумент2 страницыArnis A Filipino Martial ArtAsliah Cawasa50% (2)

- Diag Connectors GuideДокумент51 страницаDiag Connectors GuideCalvin Tan YS100% (2)

- Prvih10Vlasnika 06112022Документ204 страницыPrvih10Vlasnika 06112022Amil DzankovićОценок пока нет

- G10 Physical Fitness Skill-Related FitnessДокумент32 страницыG10 Physical Fitness Skill-Related FitnessTheness BonjocОценок пока нет