Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Reporting Sexual Harassment-Claims and Remedies

Загружено:

dianerhanИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Reporting Sexual Harassment-Claims and Remedies

Загружено:

dianerhanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

http://apj.sagepub.com/ Reporting sexual harassment: Claims and remedies

Paula McDonald, Sandra Backstrom and Kerriann Dear Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2008 46: 173 DOI: 10.1177/1038411108091757. The online version of this article can be found at: http://apj.sagepub.com/content/46/2/173

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Australian Human Resources Institute (AHRI)

Additional services and information for Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources can be found at: Email Alerts: http://apj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://apj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://apj.sagepub.com/content/46/2/173.refs.html

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

173

Reporting sexual harassment: Claims and remedies Paula McDonald and Sandra Backstrom Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland Kerriann Dear Queensland Working Womens Service, Brisbane, Queensland

Sexual harassment has been documented as a widespread and damaging phenomenon yet the specific patterns of behaviour reported in alleged sexual harassment cases and the factors influencing the lodgement of formal, legal complaints have received little attention. This two-stage study explored 632 cases of sexual harassment reported to a community advocacy organisation in Queensland, Australia. Two kinds of sexual harassment are distinguished: quid pro quo harassment (an exchange for sexual favours) and hostile environment harassment (sustained unwelcome overtures). Only 10 per cent of specialised assistance cases involved quid pro quo harassment, with the remainder categorised as hostile environment claims, including sexual remarks, physical contact and sexual gestures. Organisational responses to many of the allegations of sexual harassment were inadequate. The seriousness of many claims was also concerning, although the gravity of the harassment was not closely linked with the likelihood of a complaint being formally lodged. Most cases in one of three state/ Commonwealth commissions involved a conciliation conference and financial settlement, averaging A$5289. The study has implications for womens equal opportunity. Among these, the study suggests that complaints encountered long delays and received small settlements incommensurate with harm. This suggestion recognises the needs to search for other solutions to sexual harassment.

Keywords: gender, sexual harassment, women and employment

Correspondence to: Dr Paula McDonald, Senior Lecturer, School of Management, Faculty of Business, Queensland University of Technology, GPO Box 2434, Brisbane, Qld 4001; e-mail: p.mcdonald@qut.edu.au

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. Published by SAGE (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi and Singapore; www.sagepublications.com) on behalf of the Australian Human Resources Institute. Copyright 2008 Australian Human Resources Institute. Volume 46(2): 173195. [1038-4111] DOI: 10.1177/1038411108091757.

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

174

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Introduction Sexual harassment experienced by women in the workplace has been documented as a widespread and damaging phenomenon. Prevalence rates across a wide range of industries, occupations, and locations have been cited as high as 50 per cent (Crocker and Kalemba 1999; Illies et al. 2003) and the effects include job dissatisfaction, absenteeism, low self-esteem, and elevated stress (Kauppinen-Toropainen and Gruber 1993; Schneider, Swan, and Fitzgerald 1997). It has been estimated that sexual harassment costs organisations hundreds of millions of dollars per year in lost productivity and decreased efficiency (Faley et al. 1994). However, the specific patterns of behaviour reported in alleged sexual harassment cases and the factors influencing the lodgement of formal legal complaints have received little attention. The current paper begins to address these gaps in the literature by exploring the details of complaints made to a community organisation, the Queensland Working Womens Service (QWWS), which provides information and advocacy for working women in Queensland, Australia. As such, the focus of the paper is on working women who have concerns about sexual harassment at work, although it is acknowledged that smaller proportions of men also experience sexual harassment and that harassment also occurs in other contexts. We begin the paper by briefly reviewing the definitions, theoretical explanations, legal considerations and prevalence of sexual harassment in Australia and other industrialised countries. The paper then presents the findings of the research which address the nature and patterns of all cases of sexual harassment reported to the organisation over a three-year period, subsequently mapping the processes and outcomes of industrial proceedings for the group of women who pursued formal redress. The implications of the findings, in terms of the way in which women experience sexual harassment and how organisations might respond appropriately to this problem, are then discussed. The study contributes to an understanding of how the conditions and practices affecting female employees within given employment arrangements may facilitate or constrain the opportunities for equal participation in the workplace.

Sexual harassment in context

Sexual harassment is defined by the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 as an unwelcome sexual advance, or an unwelcome request for sexual favours or other unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature in circumstances in which a reasonable person would have anticipated that the person harassed would be offended, humiliated or intimidated (Section 28A). Sexual harassment is distinguished from other forms of harassment (e.g. racial harassment) because it considers the salience of power relations between men and women and because, unlike other forms of harassment such as those based

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

175

on race or disability, the conduct may be excused as welcome attention (Samuels 2003). Sexual harassment in employment is unlawful when an employee is applying for a job, during the course of employment, or if they are dismissed from employment because they reject the harassers advances (CCH Industrial Law Editors 1992). In order to seek redress, employees making a complaint about sexual harassment must choose to bring their complaint under either the federal act or the relevant state law. At the federal level, complaints of sexual harassment are made to the Sex Discrimination Commissioner and hearings are conducted by the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. At the state level in Queensland, the Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 requires that complaints are made to the Anti-discrimination Commission and heard by the Anti-discrimination Tribunal (CCH Industrial Law Editors 1992). Cases of unfair dismissal which have involved sexual harassment as a factor in the process of termination of employment can also be argued in the Industrial Relations Commission in Queensland under certain circumstances. A range of factors may influence or determine the choice of jurisdiction, such as corresponding provisions across federal and state acts, maximum limit for damages, and time limits set for lodging a complaint (CCH Industrial Law Editors 1992). Similar legislation as that in Australia exists in the United Kingdom (Sex Discrimination Act 1975) and the United States (Title VII of the Civil Rights of 1964) (Samuels 2003). Financial compensation following a successful hearing varies widely. For example, financial compensation received by complainants to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) during 2001/2002 varied from A$500 to A$200 000, and was most often paid by employers, because of vicarious liability, rather than the individual harasser (HREOC 2004). Explanations for why sexual harassment occurs are numerous and crossdisciplinary. While a thorough analysis of these theories is beyond the scope of this paper, a brief overview of the various positions provides some relevant background. Explanations have included: natural attraction-biological forces (Tangri, Burt, and Johnson 1982); learned or conditioned behaviours in organisations, where the exhibition of behaviours are in accord with existing societal sex-role definitions (Terpstra and Baker 1991); organisational approaches which view sexual harassment as a simple abuse of power made possible by the structure of the organisation (Tangri, Burt, and Johnson 1982); and feminist theories which contend that sexual harassment is intentional behaviour designed to maintain a position of power (Farley 1978; Gutek 1985; Terpstra 1997). The natural attraction and organisational power positions have received little empirical support in the literature (Crocker and Kalemba 1999), while studies applying sex-role theory have found that the theory explains some kinds of milder forms of sexual harassment (Padavic and Orcutt 1997). Feminist theories that focus on power relations as a central feature have become a more widely accepted explanation of the problem in

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

176

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

the academic literature (Cockburn 1991; Samuels 2003). Feminist theories contend that sexual harassment is not simply an aberration or individual misconduct but either a form of violence against women or a manifestation that is rooted in a deeply gendered and patriarchal society (Samuels 2003). Feminist theories of sexual harassment also acknowledge that power is a complicated and variable concept and may differ on issues of race and class (Brant and Too 1994). Two major forms of sexual harassment have been recognised as they occur in employment contexts. The first type of sexual harassment is accompanied by employment threat or benefit, such as when a submission to an unwelcome sexual advance is an expressed or implied condition for receiving benefits or refusal to submit to the demands results in the loss of a job benefit or in discharge. The second type of sexual harassment involves relentless and continuing unwelcome sexual conduct that interferes with an employees work performance or where a reasonable person would view it as an intimidating, humiliating or offensive work environment (CCH Industrial Law Editors 1992). Terpstra (1996, 304) distinguishes between these two types of harassment as quid pro quo harassment (where unwelcome sexual behaviour is linked to tangible job benefits), which is clearly actionable, and hostile environment claims of sexual harassment, the definitions of which are unclear and inconsistent. Crocker and Kalemba (1999) argue that this distinction perpetuates the common view that hostile or poisoned environment claims are less serious than quid pro quo harassment. Recently in the United States, however, hostile work environment claims have evolved from sexual harassment paradigms inextricably linked to sexual conduct, to a broader approach to understanding both sexual and non-sexual conduct which demeans, denigrates or otherwise deprives an individual of opportunities because of the persons gender (Tomkowicz 2004). Notwithstanding these discussions of the way sexual harassment is interpreted and applied, little empirical data confirms the relative likelihood of quid pro quo versus hostile environment harassment claims progressing to formal avenues of redress, nor the relative seriousness of each of these types of claims. Further, the extent to which quid pro quo harassment versus hostile environment claims are perpetrated by supervisors/employers as opposed to coworkers, is unknown. However, it seems probable that supervisors are more likely to use stronger expert and referent power strategies including coercions, rewards and retaliation (quid pro quo harassment) whereas co-workers are more likely to use only weak power tactics, designed to diminish the victims power or standing (Goldberg and Zhang 2004). Inconsistencies of interpretation and perceptions of behaviours that constitute sexual harassment have been argued to rest on individual differences, particularly gender, age and race. For example, older white women have been found to express the broadest definition and be more likely to define offensive behaviour as sexual harassment (Neuman 1992). The incidence and job-related

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

177

outcomes of sexual harassment are also moderated by affiliation with traditional cultures (Shupe et al. 2002). Terpstra (1996) notes that the confusion about the standard by which a hostile or abusive environment should be judged, such as the frequency of the conduct, its severity, and whether it is physically threatening or humiliating, highlights the importance of further research in this area.

Prevalence of sexual harassment

In the past two decades, sexual harassment in the workplace has become recognised as a serious social issue (Crocker and Kalemba 1999; Samuels 2003), yet a continued, high frequency of occurrence of the problem has been widely documented. Reports of prevalence rates of sexual harassment are generally derived from two major sources. The first source of information is studies that randomly sample working women across the community or within an industry or organisation and ask if they have experienced harassing behaviour within a specified timeframe. For example, a study commissioned by the Australian HREOC involved a national telephone survey examining the incidence and nature of sexual harassment in a large, random sample (over 1000 participants) of the general community (HREOC 2004). Overall, 28% of adult Australians had experienced sexual harassment at some time; 41% of women and 14% of men. Forty per cent of interviewees rated the sexual harassment experienced as very or extremely intimidating and 50% as very or extremely offensive, with female interviewees more likely to rate the sexual harassment as offensive or intimidating than male interviewees. Over two-thirds of the targets of workplace sexual harassment did not formally complain because they believed there would be no management support, a finding that is supported by other research (e.g. Firestone and Harris 2003; Union Research Centre on Organisation and Technology 2005). Further, co-workers were the most likely harassers with employers/supervisors making up approximately one-third of those responsible (HREOC 2004). Harassment was also perpetrated by coworkers more often than supervisors in a study of employed women in Perth, Australia (Savery and Halsted 1989). The high incidence of sexual harassment in Australia has been mirrored in other countries. In the United Kingdom in the 1980s, Gutek, Cohen and Konrad (1990) found that approximately 50% of employees report social-sexual behaviour at work as a problem and around 10% of women had quit jobs because of sexual harassment. A similar prevalence of sexual harassment was found in a nationally representative sample of Canadian women between 18 and 65, where 56% had experienced sexual harassment in the year prior to the survey (Crocker and Kalemba 1999). Nearly half of these incidents involved co-workers and fellow employees, while clients/customers and workplace superiors constituted 30% and 23% of episodes, respectively (Crocker and Kalemba 1999).

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

178

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Organisational characteristics appear to have a significant impact on the extent to which sexual harassment occurs in employment settings. A metaanalytic review of the incidence of sexual harassment in the United States revealed that the problem is more prevalent in organisations characterised by relatively large power differentials between organisational levels (Illies et al. 2003). Based on more than 86 000 respondents from 55 probability samples, Illies et al. (2003) found that 24% of women reported having experienced sexual harassment at work, with lower reported incidences in the academic sector and higher reported incidences for military samples. In a UK study, work setting characteristics such as occupation and seniority were stronger predictors of self-reported harassment than personal demographics such as age or marital status (Burke 1995). The second major source of information about the prevalence of sexual harassment is derived from state and Commonwealth commission data, which specifies the proportion of all work-related complaints accepted on the grounds of sexual harassment. For example, of the 812 work-related complaints accepted by the Anti-Discrimination Commission of Queensland (ADCQ) during 2005/2006, 13.2% were on the grounds of sexual harassment (ADCQ 2006). Sparked by annual complaints figures which demonstrated that sexual harassment remains a significant percentage of complaints to industrial tribunals, the Australian HREOC recently reviewed 152 complaints made to it of sexual harassment in Australian workplaces (HREOC 2004). The review found that at least 77% of all complainants had either left the organisation where the alleged harassment occurred or taken leave, representing a considerable cost in recruitment, training and development. Indirect costs associated with loss of staff morale inevitably arising from unresolved disputes within workplaces were also cited. Further, the complaints review demonstrated that sexual harassment occurred across businesses of different sizes and that almost a quarter (23%) of reported cases involved sexual physical behaviour, indicating a degree of seriousness that required urgent action by employers (HREOC 2004). It is difficult to estimate the prevalence of very extreme forms of sexual harassment such as sexual assault or gendered violence in the workplace, as rigorous research is not available. Despite the important contribution of both random-sample surveys and commission data in acknowledging the prevalence of sexual harassment both locally and internationally, information about the patterns of behaviours across industries, and the pathways taken to formal redress, remains relatively limited in the academic literature. We report on another rich source of information related to sexual harassment that appears not to have been explored previously the details of complaints made to a not-for-profit organisation in the community sector that provides advice, information and advocacy for working women. The qualitative data used in the study has two major advantages. The first advantage is that it includes the details of the process of formal avenues

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

179

of redress that are generally not available in numerical-level data sets collected by state and Commonwealth commissions. The second advantage of this data is that it contains descriptions of many instances of harassment that, for a range of reasons, never progress to formal complaints to any of the commissions, thereby allowing for a more in-depth analysis of internal labour market processes relating to sexual harassment.

Organisational context and research questions

QWWS is one of a group of community-based organisations throughout Australia that specialises in the provision of free and confidential information, advice and advocacy for working women. The agencies were established in 1994 through a federal government grant and the service receives an average of 80 calls per week requiring specialised assistance or intensive advocacy. Data collected by QWWS helps to identify the experiences of women in Queensland-based workplaces that are characterised by lower rates of unionism, smaller numbers of employees, often in the private sector, and within certain industries, particularly clerical, sales and personal services. Advisory services, mediation/conciliation and/or legal processes may be provided to women by QWWS, depending on individual situations and organisational resources and funding priorities. The current research will explore the details of over 600 cases of sexual harassment reported to the agency over a three-year period. The study will first address the nature of cases of specialised assistance dealt with by the agency and, second, document and diagrammatically map the progress of more intensive episodes that proceeded to industrial case work. The former stage of analysis will identify the patterns of behaviour that constitute sexual harassment as they occur in contemporary workplaces and provide insights about internal labour market issues that lead to these claims. The details of cases that were more likely to proceed to formal complaint will also be explored. The latter stage of analysis will focus on the process of examining complaints and reported concerns about sexual harassment from initial enquiry through to mediation/conciliation or legal proceedings and financial settlement, thereby identifying through concept maps the proportion of concerns that were dealt with in specific ways at each point in the remedy process. The specific research questions that will be addressed are: What is the nature of internal labour-market processes/concerns occurring in Queensland workplaces in relation to sexual harassment that leads to an enquiry to QWWS? What factors influence an initial enquiry to QWWS to proceed to a formal complaint at a state or Commonwealth commission? What are the processes and outcomes of reports of sexual harassment as they progress from initial enquiry to advocacy and legal procedures?

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

180

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of 632 episodes of enquiry related to sexual harassment to QWWS between 1 July 2001 and 30 June 2004, all of which had received either specialised assistance (N = 531) or more intensive advocacy services (N = 101). These cases represented around 15 per cent of all enquires reported to the service during this period. Although there were also additional clients whose contact with QWWS had consisted of a short, single phone call, these general enquiries were not considered further. All clients in the sample were female and residing in Queensland at the time of contact. Type of assistance was coded as specialised assistance if the call was longer than five minutes in duration and case work if a woman had multiple contacts or had received intensive support or assistance over time. Case work was often undertaken where the issue was considered to be appropriate for a legal claim and the client wished to proceed with a complaint or application.

Procedure

Data was sourced from the QWWS client database and files containing information pertaining to each client. Consistent with privacy protocols, cases were de-identified prior to being compiled for analysis. The complaint did not need to be labelled as harassment by the woman herself for this code to be applied in the database. Rather, QWWS staff, who have backgrounds in industrial relations, law or social work/sciences, entered the category of enquiry in relation to circumstances or behaviours described by individual women. The analysis was undertaken by the researchers. In the first stage of analysis, text-based client records were examined for patterns and themes that provided insights about the nature of work-based sexual harassment. In the second stage of the analysis, case work notes were summarised by systematically exploring each possible step the women had gone through, such as raising allegations at the workplace level, making a complaint for legal redress, conciliation in one of the commissions, a formal hearing and/or financial settlement. That is, cases were tracked through the various agencies and systems, enabling concept maps to be developed that represented various pathways.

Analysis

The text-based data were analysed using predominantly deductive approaches and a broad a priori framework. In stage one, client records were coded according to a framework consisting of the two major and recognised forms of sexual harassment (Terpstra 1996): quid pro quo harassment and hostile

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

181

environment claims. The nature and patterns of hostile environment claims were further categorised as (i) unwanted sexual teasing, jokes, remarks, comments; (ii) unwanted looks or gestures; (iii) unwanted touching or physical contact; (iv) requests for socialisation or dates; and (v) sexual propositions unlinked to job conditions. This coding was exhaustive in that some cases involved more than one type of harassment. Whether the harassment was perpetrated by a supervisor, subordinate, co-worker or client, and the location of the harassment, was also noted where this information was available. Stage two of the research utilised an analytical framework that consisted of four temporally related groupings that represented the sequence of events undergone by women as they progressed through potential avenues of redress including (i) the circumstances surrounding the complaint; (ii) the nature of post-complaint contact at the workplace (e.g. negotiation with employer); (iii) the process of lodgement of complaints with other agencies; and (iv) outcomes of formal proceedings (e.g. financial settlement). This strategy is similar to that adopted by Hood and Boltji (1998), who tracked referrals through the child protection response system in Australia.

Limitations of the data

A number of limitations of the data are acknowledged. For example, due to the staffing imperatives of the service, which dealt with large numbers of enquiries, case notes were usually factual and brief. In-depth information about individual perceptions and reactions to the sexual harassment were not recorded. The brevity of case notes also meant that information related to all categories of analysis was not available in each case. Another limitation of the data was that it does not contain information about young women under 18 years of age. Young women who called QWWS were referred to an associated organisation that dealt with young worker issues.

Results

Specialised assistance

To explore the first research question (What is the nature and patterns of internal labour-market processes occurring in Queensland workplaces in relation to sexual harassment?) 531 specialised assistance cases were examined for information related to the position and gender of the harasser, the location of the harassment and the adequacy of organisational response. These results, including the number of cases containing information in each category, are detailed in table 1. Most harassers were in a senior position to the target, either managers/ supervisors or employers. Co-workers were also commonly reported as

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

182

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Table 1 Category

Frequencies of coding categories for sexual harassment Codable studies 396 102 135 132 27 485 481 4 504 488 16 172 14 158 8.1 91.9 96.8 3.2 99.2 0.8 25.8 34.1 33.3 6.8 N %

Position of harassers Managers/supervisors Employers Co-workers Clients/customers Gender of harassers Male Female Location of harassment Physical location of the workplace Outside immediate workplace Reported response from organisation Satisfactory Unsatisfactory

harassers while the smallest group was clients/customers. The vast majority of harassers were male, with only four cases being reported as harassment by other women. Most cases of harassment occurred at the physical location of the workplace, although 16 cases occurred outside the immediate workplace. These locations included at Christmas parties (5 cases) and other work functions (6 cases); external premises/carparks (2 cases); at work conferences (3 cases); and a work trip (1 case). These findings are reported in table 1. In 172 cases, it was reported that a complaint had been made internally in the organisation. Of these, only 14 cases indicated a satisfactory outcome such as a warning being given, mediation or disciplinary action against the offender including suspension or re-location. In many remaining cases where the lodgement of an internal complaint was indicated, women reported being ignored, victimised or defamed as a result (e.g. she told her employer who called her a slut). Four women reported that the complaint had taken a long period of time to investigate. Sometimes, the perpetrators behaviour was minimised or excused as being understandable or justified, such as in the case of a port safety officer who was told by the human resources department that: he is fatherly and just a product of his generation. In another case, a woman reported the harassment to her management committee who responded by saying that the harasser was a Vietnam veteran who was going through a hard time. In these cases, no action was taken by the organisation. Nineteen cases reported that they had been dismissed from the workplace as a result of making a complaint about sexual harassment and a further 41

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

183

women resigned as a direct result of the incident(s). In 27 cases, stress leave was reported, ranging in time from one week to seven months. Quid pro quo harassment Of the 344 cases that contained enough detail for the details of the harassment to be coded, 37 (10.6%) met the definition of quid pro quo harassment, where unwelcome sexual behaviour was linked to tangible job benefits. These cases generally involved either threatened or actual negative consequences, or coercion. In relation to threat, women reported that if they did not meet the demands of the harasser, they would lose their jobs, have their holidays withdrawn, have their pay or work hours reduced, lose duties or responsibilities or have their lives made difficult. For example, one case involving a personal assistant to the director of a finance company stated: Harasser sent caller text messages and comments. He has now bought them air tickets to Melbourne; when caller said no he threatened her that if she did not go life could be made very difficult for her . A waitress in a seafood restaurant also reported that she was Dismissed because she would not provide her boss with oral sex. In relation to coercion, women reported some promise of benefit in exchange for meeting the demands or propositions of the harasser such as pay rises, promotion, financial bonuses or the increased availability of work hours. For example, a case involving a sales representative reported: Caller went on a sales trip with new boss. Boss asked her to sleep with him on both nights, asked intrusive questions and talked about his sex life. Her position had been advertised at A$50 000. Boss said he would pay her A$35 000 and increase the salary if she performed . Another case involving an administrative assistant stated: If she wanted a raise, she had to wear a short skirt. In all but one case involving coercion as well as all cases where sanctions or negative consequences were threatened, quid pro quo harassment was perpetrated by males in more senior positions in the organisation and not coworkers or clients. Hostile environment claims The remaining cases of sexual harassment met the definition of hostile environment claims where relentless and continuing unwelcome sexual conduct interferes with an employees work performance or where a reasonable person would view it as an intimidating, humiliating or offensive work environment (CCH Industrial Law Editors 1992). Details of the cases were further coded into the five categories (see table 2): remarks, physical contact, gestures, dates and propositions (individual cases could include more than one category of harassment). Approximately half of cases involved unwanted sexual teasing, jokes, remarks or comments. These remarks often related to the size of womens

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

184

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Table 2 Category

Types of sexual harassment N 37 197 112 83 14 2 % 10.6 57.3 32.6 24.1 4.0 .06

Quid pro quo harassment Hostile environment claims Remarks Physical contact Gestures Propositions Dates

N = 344 Totals are greater than 100% because some cases were coded under more than one category

breasts and buttocks, requests to see parts of their bodies, offensive language and comments of a degrading nature. Many cases of sexual harassment in this category cannot be directly quoted due to their highly obscene nature. However, some less extreme examples include a case reported by an administrative officer in the construction industry: Employer was having an affair with one of the girls in the office and she was told: If you dont like what you see, find another job, but youve got nice tits honey ; a personal assistant to a CEO in the childcare industry: CEO made constant comments about callers appearance; and the case of a factory worker: Caller experienced many sexual remarks/comments about her breasts and body. She told the employer who said Well, you are attractive, you can expect those comments . Reports of offensive text messaging, e-mails and voicemail messages were also common; for example: Employer left offensive text message about masturbating. Around a further one-third of cases involved some kind of unwanted physical contact by the harasser. The nature of this contact included kissing, cuddling, massaging, touching, pinching, grabbing, biting, bra-flicking, hitting, licking, groping, undoing clothes, spitting and forcibly placing the womans hands on the harassers crotch. Areas of womens bodies which were particularly targeted were buttocks, thighs, breasts, necks and legs. Most seriously, there were six cases of attempted rape and one case of actual rape reported. In 83 cases unwanted gestures were noted. These included 12 cases of indecent exposure or flashing. For example, one case involving a tavern bar attendant reported: A customer exposed his penis over the bar and attempted to get caller to touch it. This category also included 26 cases of exposing the callers to pornography, either electronically (e-mails, internet-based websites, videos) or in hard copy (magazines, calendars); and 16 cases of other harassment using electronic means. For example, a case involving an administrative worker reported: Callers boss had set up a web cam under her desk at work.

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

185

Only a small number of sexual harassment cases contained details that met the remaining definitions of sexual harassment types specified a priori, that is, unwanted requests for socialisation or dates (2 cases) and sexual propositions unlinked to job conditions (14 cases). An example of the latter category was that of an assistant in nursing in an aged care facility: Callers senior co-worker entered her room in the nurses quarters and propositioned her.

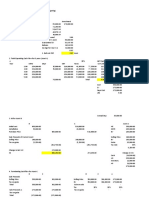

Case work: Outcomes of formal proceedings

To explore the second research questions (How do reports of sexual harassment progress from initial enquiry to advocacy and legal procedures?), 101 case work episodes were examined. Of these, 80 complaints were formally lodged with a relevant commission: 68 to ADCQ, 6 to HREOC and 6 to the Queensland Industrial Relations Commission. The latter cases involved unfair dismissal as a component of the complaint. The majority of formal complaints were lodged with ADCQ because, unlike HREOC, the ADCQ has a local presence and generally shorter waiting times. However, numerous cases did not reach conciliation stage within six and sometimes twelve months of lodgement of the complaint. In some cases respondents would not co-operate with the conciliation process leaving women in the position to decide whether to take the matter further to formal hearing. Five cases involved QWWS staff facilitating intensive mediation between the complainant and employer and a further 16 cases received counselling or ongoing support by QWWS staff. Of the 80 formal complaints lodged, 79 were accepted and proceeded to a conciliation conference performed by the various commissions. The complaint that was rejected was done so after preliminary investigations by the commission. Of the 79 cases that went to a conciliation conference at one of the commissions, financial settlement was achieved in 52 of these cases. No settlement occurred in an additional 14 cases, meaning that no conciliated agreement could be reached between the complainant and the alleged harasser. One case proceeded from conciliation conference to tribunal and in this case the complainant received A$20 000 compensation. In 11 of the 79 conciliation conference cases, the service had no further contact with the client, and postconciliation conference settlements or outcomes were unknown. The majority of cases proceeding to conciliation conference reached some kind of settlement, including general financial compensation, specific compensation for lost wages, medical/counselling treatments, statements/letters of apology, references for employment, agreements over confidentiality or withdrawal of further claims. In the cases that were financially settled and the amount was documented (27 of 52 cases), the dollar value ranged from A$865 to A$23 000, with a mean settlement amount of A$5289. While in some cases the higher settlements were associated with more severe cases of sexual harassment, there were numerous cases of severe harass-

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

186

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

ment that did not reach conciliated outcomes or settlements. There were also numerous cases where sexual harassment complaints and applications to respective commissions were prepared by QWWS on behalf of clients but were not filed because the complainant chose not to pursue this course of action. After conciliation processes are exhausted, the matter may be referred to tribunal where the case can be argued on points of law. QWWS does not generally have the resources to assist women at this level and cases are usually referred on. It was noted in the data that only one matter was documented through its hearing process and outcome at the respective tribunal. The data also demonstrated that complaints proceeding to formal redress are not typically finalised in short periods of time. It was not uncommon for case work to remain open for longer than 12 to 18 months and in several instances lengthy post conference or pre-trial negotiations were effected to give rise to settlement. In one case settlement (A$10 000) was not reached until more than three years after the alleged harassment took place and only after the matter was referred by the agency to solicitors. The pathway of these cases of sexual harassment is illustrated in figure 1. Discussion This study investigated community agency data detailing the specific patterns of behaviour reported in alleged sexual harassment cases, the factors influencing the lodgement of formal, legal complaints and the pathways of proceedings through formal avenues of redress. The large number of complaints received by the organisation (which operates within a limited context) over a three-year period highlights that sexual harassment, despite increased community awareness of the problem, is a continuing, albeit diverse, issue in many workplaces. The seriousness of many claims is also concerning, although the gravity of the act or acts of the perpetrators does not appear to be closely linked with the likelihood of the complaint being lodged or proceeding through formal avenues.

Sexual harassment and power over women

The study revealed that more than half of harassers were senior to the complainants (either supervisors, managers, or employers) and only onequarter were co-workers. Although sexual harassment is rhetorically thought of as an act perpetrated by someone in a position of seniority or authority, Brant and Too (1994) argue that the power model of sexual harassment ignores extensive evidence suggesting that harassment from peers or juniors can be more common than harassment by people in positions of authority. Reconciling the power model of sexual harassment with studies suggesting that co-workers are the most likely harassers (e.g. HREOC 2004; Savery and Halsted 1989),

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Figure 1

Pathway of sexual harassment cases reported to QWWS from 1 July 2001 to 30 June 2004

Negotiations with employer/ internal mediation n = 5

Complaint not pursued further n=3

Counselling/support provided n = 13

Complaint lodged with HREOC n = 6 Complaint rejected n=1 Complaint lodged with ADCQ n = 68 Conciliation conference n = 79 Complaint lodged with QIRC n = 6 Financial settlement n = 52 Tribunal n = 1 Settlement $20 000 Rejected offer n=1 Outcome unknown n = 11

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Case work n =101

Sexual harassment

Reporting sexual harassment

Specialised assistance n = 496

Not settled n = 14

Accepted offer n = 27 Mean $5289

187

188

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Samuels (2003) argues that power from a feminist perspective is not a pure or unmediated force but an amalgam of influences with material contexts:

When men and women enter the workplace they also bring with them the dominant ideology from outside the workplace. In society, the balance of power lies with men and even if women are in more senior positions they are made more vulnerable by the fact they are women. (Samuels 2003, 477)

The higher proportion of harassment involving superiors in this study is likely to be because the data was derived from women reporting the harassment to an external advocacy organisation. Given the threat of job loss and other sanctions evident in many cases, it is not surprising that women would seek assistance outside the immediate organisational environment. Cases of (the generally more serious) quid pro quo harassment were almost exclusively perpetrated by someone more senior in the organisation, rather than co-workers or clients. Although this is not unexpected given that employers and managers are in positions where they can exert greater organisational power than co-workers in the form of coercion, rewards or sanctions (Goldberg and Zhang 2004) which characterise quid pro quo harassment, the finding suggests that some men will exercise power to the full extent that is available to them. That is, even though their organisational seniority lends itself to legitimate power anyway, some managers and employers extend this authority and control in castigatory ways as well. Only a small proportion of perpetrators were customers or in receipt of services from the target. This type of harassment is receiving increasing attention in the literature (Guerrier and Adib 2000), not least because most organisations, even those which are intolerant of harassment by fellow employees, often have no clear policies for dealing with this type of behaviour from clients (Handy 2006). The persistence of insidious and widespread sexual harassment revealed in this and other studies indicates a resistance by organisations to defining and addressing the main problems for working women, whether they be biological bulwarks, gender relations, or workplace structures. Unsatisfactory organisational responses such as delayed investigations, a devaluing of harm done, and justifications of harassers behaviours as acceptable prompted many women to go outside their own work environments and report their experiences of sexual harassment to an external advocate. Worse still, some women who challenged the harassment through organisational channels reported being isolated, discredited, and subjected to open hostility, or receiving threatened or actual dismissal as a result of making a complaint. Previous research also suggests that management may tacitly collude with harassers actions, diminishing the possibility of successful action (Handy 2006). Inadequate organisational responses to allegations of sexual harassment increase the risk of complainants going public, voicing their disapproval outside the organisation or mounting

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

189

legal cases, which may also be costly in terms of legal fees, settlement payments and damaged reputations. The cases of stress-leave reported in this data, in addition to the more hidden costs of hiring and retraining new staff following resignations or dismissals, are also expensive consequences. Conversely, punitive responses to allegations of harassment are likely to reduce reporting rates in the future (Perry, Kulik, and Schmidtke 1998), and some managers may well use this to their advantage. Clearly, developing appropriate policies and consistently implementing corrective action is a difficult task for any organisation, especially as a case of egregious sexual harassment to one individual may not seem like a serious matter to another (Jensen and Kleiner 1999). For example, a study by Gunsch (1993) highlights the disparity between the views of executives and employees in perceptions of organisations fair dealings with claims of sexual harassment. In their national survey, 80 per cent of human resource executives stated that the punishment of offenders was just, while 60 per cent of non-HR respondents said the charges are either completely ignored or that offenders receive only token reprimands. However, the close association between organisational structures, policies and practices which address sexual harassment and the degree to which it occurs, cannot be understated. Even in male-dominated work contexts where women are more likely to experience harassment (Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Timmerman and Bajema 1999), the effect is moderated by organisational tolerance to harassment, regardless of sex ratios and organisational tasks (Handy 2006). Thus, recognising the full range of behaviours and sources associated with sexual harassment, providing education and documentation of clear policies and practices in workplaces as well as taking decisive and appropriate action when it occurs, are essential prerequisites to allowing women to overcome unequal labour-market opportunities based on factors such as greater family and domestic responsibilities and imbalanced power relations.

Manifestation of sexual harassment in workplaces

Many of the incidents coded as Remarks in the current study were intimidating, obscene and highly derogatory, sometimes resulting in extreme distress, feelings of powerlessness, sick leave and resignations. Although verbal harassment may appear to be less threatening and more socially acceptable than other forms of harassment which involve physical contact, Cleveland, Vescio, and Barnes-Farrell (2005) write that humour, jokes and even more general work language often reinforce and perpetuate discrimination and harassment in socially acceptable ways. Furthermore, when women do not laugh at stupid, harmless jokes, they are often accused of not having a sense of humour (Benokratis 1997). Verbal harassment or excluding behaviours should not be overlooked as potentially serious and damaging forms of harassment. In a similar way to verbal forms of harassment, cases involving technology

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

190

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

such as mobile phones, e-mail and the internet may appear less threatening because they can be carried out without face-to-face contact. However, this form of harassment may be as distressing as more physical forms, at least partly because it allows greater access to the complainants, both in terms of location (such as outside the immediate workplace) and time (beyond work hours). In the complainants favour though, this form of harassment is one of the few types where tangible evidence can be provided against the harasser because many of these forms of communication can be stored and traced if necessary. There appears to be a consensus in the literature that women respond more assertively to more severe forms of harassment (Cochran, Frazier, and Olsen 1997; Gruber and Smith 1995). This may account for the relatively few complaints in relation to the two categories: unwanted requests for dates and propositions. It is likely that women respond to these forms of harassment (which may be less serious or intimidating) using internal processes and without resorting to seeking external advice or assistance. Thus, although most cases were relatively serious, it is likely that the occurrence of more minor cases, where women are less likely to complain to external parties (Firestone and Harris 2003), are far more common than the data would indicate.

How sexual harassment claims progress to formal proceedings

The details of many of the specialised assistance cases reported here would certainly be viewed by a reasonable person, as the definition relays, as intimidating, humiliating or offensive (CCH Industrial Law Editors 1992) and appeared to constitute adequate grounds for lodging a complaint with one of the commissions. This is especially so for the 37 cases of quid pro quo harassment that were more apparently actionable (Terpstra 1996). In reality though, only one-sixth of overall cases were lodged as formal complaints and many cases of quid pro quo harassment did not proceed to formal redress. This finding highlights that the subjective seriousness or actionable nature of the sexual harassment is unlikely to be the most influential factor affecting whether or not the case goes to formal proceedings. Rather, the willingness of the individual to undergo the time-consuming, demanding and invasive process of challenging the harassment in a formal setting is likely to play a major part. Samuels (2003) suggests that the feminist analysis of sexual harassment should be recognised by the legal system and seen in a similar way to other feminist concerns such as rape and domestic violence if it is to be dealt with effectively. However, even if sexual harassment was recognised in the legal system as intentional behaviour designed to maintain a position of power (Terpstra 1997), this would not address the strong disincentive of the process itself. With the exception of the one individual whose case proceeded to formal trial, the average dollar value of compensation provided following settlement at a conciliation conference was just in excess of A$5000. However, this finding

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

191

must be interpreted with caution as only half of cases where settlement occurred indicated a monetary amount.

Limitations and future research

A number of limitations of the study are acknowledged. One of these limitations, often apparent in secondary data sets, includes inconsistent detail in the data records, where some cases were recorded with only brief information and others with greater detail. This inconsistency was sometimes a situational imperative where it was inappropriate at the time of initial contact to ask women for personal information, especially if they were distressed. In other cases, gaps in information were related to less-experienced staff or the time constraints of the service, which operates on a relatively small budget considering the large numbers of enquiries it deals with each day. Further, information related to longer term psychological and employment outcomes was not available. These outcomes receive little attention in the literature to date and warrant investigation in future primary research. Data collected by QWWS helps to identify the experiences of women in Queensland-based workplaces that are characterised by lower rates of unionism, smaller numbers of employees, often in the private sector, and within certain lower skilled industries, particularly clerical, sales and personal services. The data also includes a disproportionate number of indigenous women and those from non-English speaking backgrounds, groups that experience more sexual harassment (DeFour 1990; Murrell 1996) because of their limited means of asserting and maintaining power (Carli 1999; Pryor and Whalen 1997). Thus, the generalisability of the findings should be considered in light of this particular data set which provides an indication of the nature of sexual harassment experienced by relatively vulnerable groups of women employed in precarious sectors in Queensland, Australia. Importantly though, it is these very sectors, which are characterised by relatively large power differentials between organisational levels, where sexual harassment is most likely to occur (Illies et al. 2003). Within these sectors, we would also expect a reasonable level of generalisability to other Australian states, given that the distribution of employment and types of industrial arrangements do not markedly vary across states, and even to other industrialised countries, based on the consistent prevalence of sexual harassment found in large-scale studies in different nations. However, future research would need to confirm the consistency of the findings in different geographic areas. Another limitation of the study is that the data reported are based on complaints that are not verifiable. It has been argued previously that the prevalence of some complaints made by women about events in the workplace is overestimated, or what Magley et al. (1999) refer to as the whiner hypothesis. However, a meta-analysis by Illies et al. (2003) in relation to sexual harassment revealed that the rate of sexual harassment reports (by womens own definitions)

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

192

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

was less than half the incidence of reports of potentially harassing incidents believed by researchers to constitute sexual harassment. These results also show that women are reluctant to label offensive experiences as sexual harassment and, more often than not, do not report harassing incidents, thus constituting strong evidence against the whiner hypothesis. The fact that many women reported they had already made a complaint to someone in their organisation may suggest that dealing with the issue internally is the preferred option for women who experience sexual harassment at work as a first port of call. Conclusions It is apparent that, despite 20 years of legislation outlawing sexual harassment, it is still a common occurrence in contemporary workplaces. Previous literature suggests that the allegations of sexual harassment examined in this study are likely to represent only the tip of the iceberg, with the number of reports to statutory agencies and other organisations well below the number of incidents which actually occur. In many documented cases, responses from workplaces were unsupportive, minimising and isolating, given they did not effectively recognise the concerns of the woman involved. Such responses sometimes led to loss of employment, either directly or indirectly. In a small proportion of sexual harassment cases, women followed up their concerns in a jurisdictional forum and received financial settlements, although these were often only comparable to a few weeks wages and likely under-compensated the complainant for the distress and loss of income related to the harassment. The lengthy amount of time apparent in the data before the issues of sexual harassment are addressed poses extended risks to women of increased trauma and damage, both financial and psychological. These risks in turn, increase vicarious liability for employers and potential exposure to workers compensation claims, though this was not specifically identified in this data-set. Although legislation and policy can provide guidelines as a basis for prevention and action, sexual harassment persists as a problem for high numbers of women and for their employers, whose obligations extend to establishing, maintaining and enforcing guidelines for appropriate practices and behaviours. This study has demonstrated the need for a more proactive, preventative, and broad-sweeping educative approach as to the unacceptable nature of sexual harassment in workplaces generally and the damage and impact on those who are targeted in its path.

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

193

Paula McDonald (PhD) is a senior lecturer in the School of Management, Queensland University of Technology. Paulas research areas include discrimination and harassment in employment, worklife balance, and youth employment. She works closely with several community and public sector organisations in Queensland. Sandra Backstrom is a research associate in the School of Management, Queensland University of Technology. Sandras research has included studies of sexual harassment and discrimination at work, equity in higher education curriculum, and work and popular culture. Kerriann Dear is the director of the Queensland Working Womens Service. Kerriann provides assessment, intervention, and intensive case work and case management, counselling, and support services to working women, as well as broader roles including advocacy and policy analysis.

References

ADCQ. 2006. Annual report of the Anti-discrimination Commission Queensland 20052006. Brisbane: ADCQ. Benokratis, N.V. 1997. Subtle sexism: Current practices and perspectives for change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bond, C. 1997. Resolving sexual harassment disputes in the workplace: The central role of mediation in an employment contract. Dispute Resolution Journal 52(2): 1585. Brant, C., and Y. Too. 1994. Rethinking sexual harassment. London: Pluto Press. Burke, R.J. 1995. Incidence and consequences of sexual harassment in a professional services firm. Employee Counselling Today 7(3): 2330. Carli, L.L. 1999. Gender, interpersonal power and social influence. Journal of Social Issues 55(1): 8199. CCH Industrial Law Editors. 1992. Countering sexual harassment: A manual for managers and supervisors. Sydney: CCH. Cleveland, J.N., T.K. Vescio, and J.L. Barnes-Farrell. 2005. Gender discrimination in organisations. In Discrimination at work: The psychological and organizational bases, eds R. Dipboye and A. Colella. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Cochrane, C.C., P.A. Frazier, and A.M. Olson. 1997. Predictors of responses to unwanted sexual attention. Psychology of Women Quarterly 21(2): 20726. Cockburn, C. 1991. In the way of women: Mens resistance to sex equality in organisations. London: Macmillan Press. Crocker, D., and V. Kalemba. 1999. The incidence and impact of womens experiences of sexual harassment in Canadian workplaces. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 36(4): 54159. DeFour, D.C. 1990. The interface of racism and sexism on college campuses. In Ivory power: Sexual harassment on campus, ed. M. Paludi, 4552. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Faley, R.H., D.E. Knapp, G.A. Kustis, and C.L. DuBois. 1994. Organizational cost of sexual harassment in the workplace. Paper presented at the Ninth Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, May, in Nashville, Tennessee. Farley, L. 1978. Sexual shakedown: The sexual harassment of women on the job. New York: McGraw-Hill. Firestone, J.M., and R.J. Harris. 2003. Perceptions of effectiveness of responses to sexual harassment in the US military, 1988 and 1995. Gender, Work and Organization 10(1): 4364.

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

194

Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources

2008 46(2)

Fitzgerald, L.F., F. Drasgow, C.L. Hulin, M.J. Gelfand, and V.J. Magley. 1997. Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology 82(4): 57889 Goldberg, C., and L. Zhang. 2004. Simple and joint effects of gender and self-esteem on responses to same-sex sexual harassment. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 50(11/12): 82333. Gruber, J.E., and M.D. Smith. 1995. Womens responses to sexual harassment: A multivariate analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 17(4): 54362. Guerrier, Y., and A. Adib. 2000. No, we dont provide that service: The harassment of hotel employees by customers. Work, Employment and Society 14(4): 689705. Gunsch, D. 1993. Fair punishment for sexual harassment offenders is a matter of perspective. Personnel Journal 72(1): 23. Gutek, B.A. 1985. Sex and the workplace: The impact of sexual behaviour and harassment on women, men and organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Gutek, B., A. Cohen., and A. Konrad. 1990. Predicting social-sexual behavior at work: A contact hypothesis. Academy of Management Journal 33: 56077. Handy, J. 2006. Sexual harassment in small-town New Zealand: A qualitative study of three contrasting organizations. Gender, Work and Organization 13(1): 124. Hearn, J., and W. Parkin. 1987. Sex at work. New York: St Martins Press. Hood, M., and C. Boltje. 1998. The progress of 500 referrals from the child protection response system to the criminal court. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 31: 18295. Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. 2004. Sexual harassment 20 years on: Sexual harassment in the Australian workplace. Canberra: HREOC. Illies, R., N. Hauseman, S. Schwochau, and J. Stibal. 2003. Reported incidence rates of workrelated sexual harassment in the United States: Using meta-analysis to explain reported rate disparities. Personnel Psychology 56(3): 60718. Jensen, K., and B.H. Kleiner. 1999. How to determine proper corrective action following sexual harassment investigations. Equal Opportunities International 18(24): 239. Kauppinen-Toropainen, K., and J. Gruber. 1993. Antecedents and outcomes of woman unfriendly experiences: A study of Scandinavian, former Soviet and American women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 17: 43156. Magley, V.J., C.L. Hulin, L.F. Fitzgerald, and M. DeNardo. 1999. Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology 84(3): 390402. Murrell, A.J. 1996. Sexual harassment and women of color: Issues, challenges and future directions. In Sexual harassment in the workplace: Perspectives, frontiers, and response strategies, ed. M.S. Stockdale, 5166. London: Sage. Neuman, L.W. 1992. Gender race and age differences in student definitions of sexual harassment. Wisconsin Sociologist 29(2/3): 6375. Padavic, I., and J.D. Orcutt. 1997. Perceptions of sexual harassment in the Florida legal system: A comparison of dominance and spillover explanations. Gender and Society 11: 68298. Perry, E.L., C.T. Kulik, and J.M. Schmidtke. 1998. Individual differences in the effectiveness of sexual harassment awareness training. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 28(8): 698723. Pryor, J.B., and N.J. Whalen. 1997. A typology of sexual harassment: characteristics of harassers and the social circumstances under which sexual harassment occurs. In Sexual harassment: theory, research and treatment, ed. W. ODonahue, 12951. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Samuels, H. 2003. Sexual harassment in the workplace: A feminist analysis of recent developments in the UK. Womens Studies International Forum 26(5): 46782.

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Reporting sexual harassment

195

Savery, L.K., and A.C. Halsted. 1989. Sexual harassment in the workplace: Who are the offenders? Equal Opportunities International 8(2): 1621. Schneider, K.T., S. Swan, and L.F. Fitzgerald, 1997. Job related and psychological effects of sexual harassment in the workplace: Empirical evidence from two organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology 82(3): 40115. Shupe, E.I., L.M. Cortina, A. Ramos, L. Fitzgerald, and J. Salisbury. 2002. The incidence and outcomes of sexual harassment among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: A comparison across levels of cultural affiliation. Psychology of Women Quarterly 26(4): 298309. Tangri, S., M.R. Burt, and L.B. Johnson. 1982. Sexual harassment at work: Three explanatory models. Journal of Social Issues 38(4): 5574. Terpstra, D.E. 1996. The effects of diversity on sexual harassment: Some recommendations for research. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 9(4): 30312. Terpstra, D.E. 1997. Recommendations for research on the effects of organisational diversity on women. Journal of Business and Psychology 11(4): 48592. Terpstra, D.E., and D.D. Baker. 1991. Sexual harassment: Psychosocial issues. In Vulnerable workers: Psychosocial and legal issues, eds M.J. Davidson and J. Earnshaw, 179201. Chichester, UK: Wiley. Timmerman, G., and C. Bajema. 1999. Incidence and methodology in sexual harassment research in northwest Europe. Womens Studies International Forum 22(6): 67381. Tomkowicz, S. 2004. Hostile work environments: Its about the discrimination, not the sex. Labor Law Journal 55(2): 99112. Union Research Centre on Organisation and Technology (URCOT). 2005. Safe at work? Womens experience of violence in the workplace: Summary report of research. Melbourne: URCOT.

Downloaded from apj.sagepub.com by dian erhan on October 13, 2010

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Counsellor Response To Clients' Metaphors An Evaluation andДокумент13 страницCounsellor Response To Clients' Metaphors An Evaluation anddianerhanОценок пока нет

- Optimism eДокумент129 страницOptimism eFarida0% (1)

- A Psychometric Analysis of A College CounselingДокумент6 страницA Psychometric Analysis of A College CounselingdianerhanОценок пока нет

- A Relationship Based On Reality and ChoiceДокумент6 страницA Relationship Based On Reality and ChoicedianerhanОценок пока нет

- 17 2752ns0812 130 134Документ5 страниц17 2752ns0812 130 134dianerhanОценок пока нет

- Violence Against WomenДокумент26 страницViolence Against WomendianerhanОценок пока нет

- 57 107 1 SMДокумент33 страницы57 107 1 SMdianerhanОценок пока нет

- Adult Survivors of Childhood AbuseДокумент14 страницAdult Survivors of Childhood AbusedianerhanОценок пока нет

- Children's Consent in Sexual AbuseДокумент33 страницыChildren's Consent in Sexual AbusedianerhanОценок пока нет

- 12 CounselingДокумент30 страниц12 CounselingdianerhanОценок пока нет

- Sexual Harassment On The InternetДокумент17 страницSexual Harassment On The InternetdianerhanОценок пока нет

- Who Have Survived Child Sexual AbuseДокумент16 страницWho Have Survived Child Sexual AbusedianerhanОценок пока нет

- Sexual Harassment On The InternetДокумент17 страницSexual Harassment On The InternetdianerhanОценок пока нет

- Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 2010 Sink 1 18Документ19 страницCounseling Outcome Research and Evaluation 2010 Sink 1 18dianerhanОценок пока нет

- Adult Survivors of Childhood AbuseДокумент14 страницAdult Survivors of Childhood AbusedianerhanОценок пока нет

- A Study of Finger Length Relation (Ring Finger & Little Finger I.E. 4D5D) With Human Personality.Документ19 страницA Study of Finger Length Relation (Ring Finger & Little Finger I.E. 4D5D) With Human Personality.danielemarzoli6150100% (2)

- Alamat Web Cerita SilatДокумент2 страницыAlamat Web Cerita SilatdianerhanОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Euro MedДокумент3 страницыEuro MedAndrolf CaparasОценок пока нет

- Introduction to Investment and SecuritiesДокумент27 страницIntroduction to Investment and Securitiesanandhi_jagan0% (1)

- 2019 Civil Service Exams Schedule (CSE-PPT) : Higit PaДокумент12 страниц2019 Civil Service Exams Schedule (CSE-PPT) : Higit PaJean LiaoОценок пока нет

- Government Subsidies and Income Support For The PoorДокумент46 страницGovernment Subsidies and Income Support For The PoorOdie SetiawanОценок пока нет

- JMRC Vacancy Circular For DeputationДокумент20 страницJMRC Vacancy Circular For DeputationSumit AgrawalОценок пока нет

- 02 Formal RequisitesДокумент8 страниц02 Formal Requisitescmv mendozaОценок пока нет

- Tumey V Ohio (Judge Compensation Issue) HTMДокумент18 страницTumey V Ohio (Judge Compensation Issue) HTMlegalmattersОценок пока нет

- V2150 Mexico CAB MU920 MU610Документ2 страницыV2150 Mexico CAB MU920 MU610RubenL MartinezОценок пока нет

- Feast of TrumpetsДокумент4 страницыFeast of TrumpetsSonofManОценок пока нет

- File No. AI 22Документ8 страницFile No. AI 22Lori BazanОценок пока нет

- AE 315 FM Sum2021 Week 3 Capital Budgeting Quiz Anserki B FOR DISTRIBДокумент7 страницAE 315 FM Sum2021 Week 3 Capital Budgeting Quiz Anserki B FOR DISTRIBArly Kurt TorresОценок пока нет

- Nit 391 Ninl Erp TenderdocДокумент405 страницNit 391 Ninl Erp TenderdocK Pra ShantОценок пока нет

- GAISANO INC. v. INSURANCE CO. OF NORTH AMERICAДокумент2 страницыGAISANO INC. v. INSURANCE CO. OF NORTH AMERICADum DumОценок пока нет

- ETHICAL PRINCIPLES OF LAWYERS IN ISLAM by Dr. Zulkifli HasanДокумент13 страницETHICAL PRINCIPLES OF LAWYERS IN ISLAM by Dr. Zulkifli HasansoffianzainolОценок пока нет

- ELECTION LAW Case Doctrines PDFДокумент24 страницыELECTION LAW Case Doctrines PDFRio SanchezОценок пока нет

- Riverscape Fact SheetДокумент5 страницRiverscape Fact SheetSharmaine FalcisОценок пока нет

- Case Digest: SUPAPO v. SPS. ROBERTO AND SUSAN DE JESUS PDFДокумент4 страницыCase Digest: SUPAPO v. SPS. ROBERTO AND SUSAN DE JESUS PDFGerard LeeОценок пока нет

- Materi 5: Business Ethics and The Legal Environment of BusinessДокумент30 страницMateri 5: Business Ethics and The Legal Environment of BusinessChikita DindaОценок пока нет

- Heirs dispute over lands owned by their fatherДокумент23 страницыHeirs dispute over lands owned by their fatherVeraNataaОценок пока нет

- CH 9.intl - Ind RelnДокумент25 страницCH 9.intl - Ind RelnAnoushkaОценок пока нет

- Full Download Understanding Human Sexuality 13th Edition Hyde Test BankДокумент13 страницFull Download Understanding Human Sexuality 13th Edition Hyde Test Bankjosiah78vcra100% (29)

- Amazon Order 19-1-22Документ4 страницыAmazon Order 19-1-22arunmafiaОценок пока нет

- Caballes V CAДокумент2 страницыCaballes V CATintin CoОценок пока нет

- Consent of Occupant FormДокумент2 страницыConsent of Occupant FormMuhammad Aulia RahmanОценок пока нет

- Us3432107 PDFДокумент3 страницыUs3432107 PDFasssssОценок пока нет

- Application Form For Combined Technical Services Examination 2017 375295489Документ3 страницыApplication Form For Combined Technical Services Examination 2017 375295489TemsuakumОценок пока нет

- Wa0008.Документ8 страницWa0008.Md Mehedi hasan hasanОценок пока нет

- Diplomacy settings and interactionsДокумент31 страницаDiplomacy settings and interactionscaerani429Оценок пока нет

- Criminal Justice SystemДокумент138 страницCriminal Justice SystemKudo IshintikashiОценок пока нет

- Legal Language PDFFFДокумент18 страницLegal Language PDFFFRENUKA THOTEОценок пока нет