Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Sex 2

Загружено:

leafar78Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Sex 2

Загружено:

leafar78Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Lung (2012) 190:545556 DOI 10.

1007/s00408-012-9398-4

COPD

Sexual Dysfunction in Men with COPD: Impact on Quality of Life and Survival

Eileen G. Collins Sahar Halabi Mathew Langston Timothy Schnell Martin J. Tobin Franco Laghi

Received: 15 February 2012 / Accepted: 28 May 2012 / Published online: 3 July 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2012

Abstract Background Most patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are middle-aged or older, and by denition all have a chronic illness. Aging and chronic illness decrease sexual interest, sexual function, and testosterone levels. To date, researchers have not simultaneously explored prevalence, risk factors, and impact of sexual dysfunctions on quality of life and survival in men with COPD. We tested three hypotheses: First, sexual dysfunctions, including erectile dysfunction, are highly prevalent and impact negatively the quality of life of those with COPD. Second, gonadal state is a predictor of erectile dysfunction. Third, erectile dysfunction, a potential maker of systemic atherosclerosis, is a risk factor for mortality in men with COPD. Methods In this prospective study, sexuality was assessed in 90 men with moderate-to-severe COPD (40

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00408-012-9398-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

E. G. Collins College of Nursing, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA E. G. Collins Research Services, Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital, 111 N 5th Avenue and Roosevelt Road, Hines, IL 60141, USA S. Halabi M. Langston T. Schnell M. J. Tobin F. Laghi (&) Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital, 111 N 5th Avenue and Roosevelt Road, Hines, IL 60141, USA e-mail: aghi@lumc.edu M. Langston T. Schnell M. J. Tobin F. Laghi Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Loyola University, Maywood, IL, USA

hypogonadal) by questionnaire. Testosterone levels, comorbidities, dyspnea, depressive symptoms, and survival (4.8 years median follow-up) were recorded. Results Seventy-four percent of patients had at least one sexual dysfunction, with erectile dysfunction being the most common (72 %). Most were dissatised with their current and expected sexual function. Severity of COPD was equivalent in patients with and without erectile dysfunction. Low testosterone, depressive symptoms, and presence of partner were independently associated with erectile dysfunction. Severity of lung disease and comorbidities, but not erectile dysfunction, were independently associated with mortality (p = 0.006). Conclusions Sexual dysfunctions, including erectile dysfunction, were highly prevalent and had a negative impact on quality of life in men with COPD. In addition, gonadal state was an independent predictor of erectile dysfunction. Finally, erectile dysfunction was not associated with allcause mortality. Keywords Endocrine Erectile dysfunction Testosterone Sexuality Aging Outcome

Introduction Most patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are middle-aged or older, and by denition all have a chronic illness [1]. Aging and chronic illness decrease testosterone levels [2], sexual interest, and sexual function, including erectile function [3, 4]. Although not universally established [58], clinical [913] and laboratory [1417] observations suggest that such decreases in sexual interest and sexual function are mechanistically linked to decreased testosterone levels.

123

546

Lung (2012) 190:545556

In nonhuman primates, high-afnity androgen receptors occur in many areas of the brain, including the orbital prefrontal cortex [14]. In healthy men, the orbital prefrontal cortex is one of the brain regions activated by visual sexual stimuli [10]. This activation is blunted in untreated hypogonadal men and it is normalized by testosterone administration [10]. Testosterone also affects local mechanisms for penile tumescence [18]. Bearing in mind the high prevalence of hypogonadism in men with COPD [19] and the mechanistic links between testosterone and sexual function [10, 18], it would appear possible to predict a link between gonadal state and sexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction (ED), in men with COPD. In *90 % of men older than 50 years, ED is due to organic causes [20], the most common of which is atherosclerosis [2123]. Differently stated, in older men ED is often the clinical manifestation of endothelial dysfunction [24] and vascular disease [23]. Not surprisingly, ED has been associated with an increased incidence of all-cause mortality, primarily through its association with cardiovascular mortality [25]. Given the high incidence of cardiovascular mortality among patients with COPD [26, 27], and the mechanistic link between ED and cardiovascular mortality [25], it would seem plausible to predict a link between ED and mortality in men with COPD. The main objectives of this study thus were to simultaneously explore three aspects of sexuality in men with moderate-to-severe COPD. One was to assess the prevalence, impact, and perceived causes of sexual dysfunctions, including ED. Two was to identify the independent predictors of ED. Specically, we hypothesized that ED would be the most common sexual dysfunction experienced by men with COPD. In addition, considering that poor sexual well-being has a negative impact on quality of life [28], we hypothesized that sexual dysfunction would negatively impact current and expected quality of life of men with COPD. The third objective was to explore the impact of EDa potential marker of systemic atherosclerosis [22, 23, 29]on the survival of men with COPD. Specically, we tested the hypothesis that ED would be an independent risk factor for mortality. This is the rst prospective study designed to explore simultaneously the prevalence, risk factors, and impact of sexual dysfunction on quality of life and survival in men with COPD.

Exclusion criteria included orchiectomy, prostatectomy, androgen and antiandrogen therapy, cirrhosis, and alcohol dependence. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study and written consent was obtained from the participants. Some aspects of data on clinical and laboratory characteristics of 45 participants have been included in a study addressing different research questions [30]. Measurements Demographic Data, Comorbidities, and Pulmonary Function Testing Demographic and clinical data were extracted from the patients medical records and self-reports [31]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Lung volumes were measured by spirometry and plethysmography. Measurements of arterial blood gases were obtained while patients were breathing room air. The age-corrected Charlson comorbidity index [32] was used to determine the impact of comorbid conditions on perceived ED and mortality. Modied Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors (GSSAB) Questionnaire The GSSAB is a questionnaire developed to conduct population studies on perceived sexual well-being in middle-aged and older adults (see online supplementary material) [28, 33]. Validity and reliability of the GSSAB have been previously reported [28, 33]. Patients were rst instructed to answer questions regarding sexual problems experienced sometimes or frequently for at least 2 months during the previous year [28, 33]. Sexual problems of interest were erection difculties, lack of interest in sex, inability to climax, and nding sex not pleasurable. Patients were also asked to rate the impact of sexual problems on quality of life (4-point Likert scale) [34], satisfaction with sexual function (5-point Likert scale) [28], and perceived reason for decreased or lack of sexual activity [35]. Shortness of Breath Questionnaire (SOBQ) The SOBQ was used to assess the severity of dyspnea with various activities of daily living, including sexual activities [36]. The reliability and validity of the SOBQ have been demonstrated previously [36]. If patients did not perform an activity listed in the SOBQ, they were instructed to give their best estimate of breathlessness [36]. Assessment of Depressive Symptoms The presence of depressive symptoms was determined using the geriatric depression scale (GDS) [30]. The GDS

Methods Patients A convenience sample of 90 outpatient men with stable COPD and who were 55 years or older was enrolled.

123

Lung (2012) 190:545556

547

is a widely used questionnaire [30, 37] with well-established validity and reliability [37]. Blood Samples Morning blood samples were collected for the measurement of free and total testosterone and for luteinizing hormone. Testosterone levels were considered low if free testosterone was \35 pg/ml in patients younger than 70 years, and \30 pg/ml in patients C70 years old [38]. These thresholds have been identied by assessing free testosterone concentrations in 264 ambulatory healthy men between the ages of 18 and 89 years who were taking no medication [38]. Protocol Patients underwent pulmonary function testing and collection of blood samples. Thereafter, they completed the modied GSSAB [33], the GDS [30], and the SOBQ [36]. Patients survival from date of enrolment through June 30, 2011 (median follow-up of 4.8 years) was prospectively obtained from the electronic medical records of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Data Analysis Comparisons between patients reporting ED and patients reporting no ED were performed using the unpaired Students t test, MannWhitney U test, and Pearson v2 test, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of clinical characteristics on ED. The independent variables for this multivariable analysis were gonadal state [1113], signicant depressive symptoms (GDS C11) [6, 39], severity of lung disease (FEV1 % predicted) [4, 40, 41], dyspnea (SOBQ) [40, 41], smoking [42, 43], Charlson score [3, 4, 6, 7, 42, 43], partner availability [7, 43], and use of medications that have been associated with ED [6]. Finally, frequencies of all-cause mortality by time of patients with and without ED were plotted using the Kaplan Meier product limit method. Log-rank test was used to compare differences between the two groups. To further explore the impact of ED on mortality, we conducted univariable analyses (Cox proportional hazards model) using potential predictors of mortality as independent variables (ED, FEV1 % predicted, BMI, Charlson, use of oral corticosteroids, PaO2, and PaCO2) and survival status as the dependent variable [44]. Independent variables associated with mortality with p \ 0.15 in univariable analyses were incorporated into a multivariable analysis (Cox proportional hazards model) [44]. Results Patients characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All had moderate-to-severe COPD, considerable hyperination, and

gas trapping. Thirty patients (33 %) were on home oxygen and 26 % retained carbon dioxide (PaCO2 [45 mmHg). Nearly two thirds of the patients were on inhaled steroids and less than 10 % was on systemic steroids. Prevalence of Sexual Dysfunction and Impact on Quality of Life Sixty-seven patients (74 %) had at least one sexual dysfunction. Most patients had difculty in achieving or maintaining an erection (Fig. 1, upper panel). A sizable minority reported lack of sexual interest, inability to achieve an orgasm, and found sex not pleasurable. The patients experience of each sexual dysfunction was more often rated as being very much of a problem or somewhat of a problem than little of a problem or not a problem (p \ 0.0005 in all instances) (Fig. 1, middle and lower panels). To assess the impact of overall sexual function on quality of life, patients were asked how they would feel if they were to spend the rest of their lives with their current sexual function [33]. To that question more patients with ED than without ED answered that they would have been somewhat dissatised or very dissatised (p \ 0.0005) (Fig. 2). The percentage of patients who would have been neither satised nor dissatised was similar in the two groups (p = 0.245). ED and Patients Characteristics The median (interquartile range, IQR) levels of total testosterone and free testosterone were 332 (range = 253409) ng/ dl and 35 (range = 2744) ng/dl, respectively, in patients without ED, and 310 (range = 222399) ng/dl and 32 (range = 2639) ng/dl, respectively, in patients with ED. The prevalence of low testosterone levels was equivalent in patients with and without ED (Table 2). LH concentration tended to be greater in patients with ED than in patients without ED (p = 0.069). Nine patients with ED (14 %) and one without ED (4 %) were prescribed a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (sildenal or vardenal). Of the nine patients with ED on a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, seven reported sexual interest, six were able to climax, and eight found sex pleasurable. The patient without self-reported ED who was on a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor considered sex pleasurable, was able to climax, and maintained interest in sex. With the exception of greater prevalence of signicant depressive symptoms (GDS C11) [30] in patients with ED than in patients without ED, all other clinical characteristics of the two groups were similar (Table 2). Severity of dyspnea associated with sexual activities (SOBQ) was similar in the two groups of patients: 3.5 0.2 in patients with ED and 3.2 0.3 in patients without ED (p = 0.31).

123

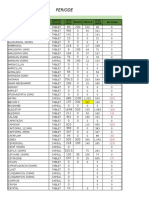

548 Table 1 Patients characteristics (n = 90) Age (years) FEV1/FVC [median (IQR)] FEV1 (L) [median (IQR)] FVC (L) Total lung capacity (L) Residual volume (L) pH [median (IQR)] PaCO2 (mmHg) [median (IQR)] PaO2 (mmHg) [median (IQR)] Inhaled corticosteroids [n (%)] Oral prednisone [n (%)] Comorbidities Coronary artery disease, heart failure [n (%)] Peripheral vascular disease [n (%)] Cerebrovascular disease [n (%)] Hypertension [n (%)] Diabetes [n (%)] Medications that could cause ED Thiazides/thiazide-like diuretics [n (%)] Values are mean SE or median and interquartile range (IQR) FEV1 forced expired volume in 1 s, FVC forced vital capacity, PaCO2 partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide, PaO2 partial pressure of arterial oxygen, ED erectile dysfunction, ACE-I angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitor, AT-II angiotensin II receptor blockers Carvedilol or propranolol [n (%)] Antidepressants (not bupropion, not trazodone) [n (%)] Antipsychotics [n (%)] Medications unlikely to cause ED Loop diuretics [n (%)] Metoprolol or atenolol Calcium channel blockers [n (%)] ACE-I or AT-II receptor blockers [n (%)] Bupropion or trazodone [n (%)] Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors 23 (26) 24 (27) 28 (31) 37 (41) 9 (10) 10 (11) 15 (17) 4 (4) 15 (17) 3 (3) 28 (31) 14 (16) 5 (6) 57 (63) 21 (23)

Lung (2012) 190:545556

Value 69 1 42 (3254) 1.35 (0.981.72) 3.28 0.10 7.4 0.2 4.3 0.2 7.42 (7.407.43) 41 (3846) 71 (6475) 53 (59) 7 (8)

% Predicted

46 (3457) 86.1 2.3 122 3 189 7

Perceived Reasons for Decreased or Lack of Sexual Activity Only a minority of patients with ED and without ED experienced no decrease in sexual activity during the previous year (Fig. 3). This percentage tended to be smaller in patients with ED (12 %) than in patients without ED (28 %, p = 0.074). The most common perceived reasons for decreased sexual activity in both groups were the belief of being too old and/or too sick (45 % in patients with ED and 24 % in patients without ED, p = 0.072) followed by other reasons (28 % in both groups) such as decreased sex drive and decreased interest, and in patients with ED, difculty achieving an erection, medications, and by the absence of partner (15 % in patients with ED and 28% in patients without ED). Forty-three patients (66 %) with ED had a partner. Of these, 8 (19 %) reported decreased sexual activity as a result of unwillingness of the partner to have sex or

because the partner was too sick or too old. In contrast, none of the 13 patients without ED who had a partner reported any sexual problems with the partner. Variables Associated with Increased Risk for ED Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that low testosterone levels (odds ratio [OR] = 3.39; p = 0.040), signicant depressive symptoms (OR = 5.62; p = 0.029), and presence of a partner (OR = 3.56; p = 0.033) were independently associated with ED after controlling for active smoking, age-corrected Charlson, severity of obstruction (FEV1 % predicted), dyspnea, and medications that could cause ED (Table 3). Mortality and Self-Reported ED Thirty-ve patients died (39 % or 9.9 events per 100 person-years) over a median follow-up period of 4.8

123

Lung (2012) 190:545556

549

Fig. 1 Top panel Perceived sexual dysfunction in 90 men with COPD who completed the modied global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors (GSSAB) questionnaire. Most patients reported erectile dysfunction; about one third or more had no sexual interest, were unable to climax, and considered sex not pleasurable. Middle and bottom panels Patients with perceived erectile dysfunction (middle left, n = 65), without sexual interest (middle right, n = 34), unable to

climax (lower left, n = 38), and unable to nd sex pleasurable (lower right, n = 25) rated their experience with that given sexual problem on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from not a problem to very much of a problem. Patients experience of each dysfunction was more often rated as being very much of a problem or somewhat of a problem than being little of a problem or not a problem (p \ 0.0005 in all instances)

123

550

Lung (2012) 190:545556

Fig. 2 Responses of patients with erectile dysfunction [ED (?), red line, n = 65] and with no erectile dysfunction [ED (-), blue line, n = 25] on how they would feel if they were to spend the rest of their lives with their current sexual function. Fewer patients with erectile dysfunction (22 %) than without it (56 %) responded that they would have been very satised or somewhat satised (p = 0.002). In contrast, more patients with erectile dysfunction (54 %) than without it (4 %) would have been somewhat dissatised or very dissatised (p \ 0.0005). The percentage of patients who would have been neither satised nor dissatised was similar in the two groups (25 and 36 %, p = 0.245)

(range = 3.45.9) years. No differences in mortality between patients with and without ED were detected by KaplanMeier analysis and the log-rank test (Fig. 4). To explore the impact of ED and other baseline characteristics on mortality, we rst conducted univariable analyses followed by multivariable analysis. ED was not related to mortality on univariable analysis (95 % CI = 0.5592.336; p = 0.716). In contrast, FEV1 % predicted, age-corrected Charlson, and daily use of oral corticosteroids were related to mortality with p \ 0.15 (Table 4). These three variables were included in the multivariable prediction model. In that model, age-corrected Charlson was the variable with the strongest relationship with mortality (p = 0.001). FEV1 %

Fig. 3 Perceived reasons for decreased sexual activity or lack of sexual activity during the previous year in 65 patients with selfreported erectile dysfunction [ED (?), red line] and in 25 patients with no erectile dysfunction [ED (-), blue line]. Only a minority of patients in both groups reported no decrease in sexual activity during the previous year. The most common causes for decreased sexual activity in both groups was the perception of being too old and/or too sick followed by other reasons. Eight patients with erectile dysfunction reported decreased sexual activity as a result of unwillingness of the partner to have sex or because the partner was too sick or too old. In contrast, no patient without erectile dysfunction reported sexual problems with their partners. (Information on the partners willingness to engage in sex was extracted from the other reasons question)

predicted maintained a signicant relationship to mortality (p = 0.006) while daily use of oral corticosteroids did not (p = 0.425).

Discussion This is the rst prospective study designed to simultaneously explore the prevalence, risk factors, and impact of

Table 2 Characteristics of men with COPD with and without self-reported erectile dysfunction Self-reported erectile dysfunction Variable Age (years) Low free testosterone [n (%)] LH (mIU/ml) [median (IQR)] Married/companion [n (%)] FEV1 % predicted [median (IQR)] Shortness of breath questionnaire (score) Signicant depressive symptoms (GDS C11) [n (%)] Age-corrected Charlson comorbidity index [median (IQR)] Medications that could cause erectile dysfunction (n) Data are mean SE, median (IQR), and percentage GDS geriatric depression scale, IQR interquartile range, FEV1 forced expiratory ow in 1 s Present (n = 65) 69 1 32 (49) 6 (47) 43 (66) 48 (3456) 54 3 28 (43) 3 (24) 0.4 0.1 Absent (n = 25) 69 2 8 (32) 5 (46) 13 (52) 40 (3258) 49 4 4 (16) 3 (24) 0.4 0.1 p Value 0.949 0.141 0.069 0.215 0.380 0.247 0.016 0.335 0.916

123

Lung (2012) 190:545556 Table 3 Multivariable logistic analysis to determine the relationship between self-reported erectile dysfunction and patients characteristics (n = 90) Variable Low free testosterone Signicant depressive symptoms (GDS C11) Companion FEV1 % predicted Shortness of breath questionnaire score Odds ratio 3.39 5.62 3.56 1.00 1.00 95 % CI 1.0610.90 1.1926.54 1.1111.47 0.961.04 0.971.03 0.718.02 0.901.84 0.332.19 p Value Univariable analysis 0.040 0.029 0.033 0.949 0.820 0.158 0.166 0.735 Age-corrected Charlson FEV1 % predicted Daily use of oral corticosteroids Multivariable analysis Age-corrected Charlson FEV1 % predicted Daily use of oral corticosteroids 1.433 0.962 0.670 1.1621.766 0.9360.989 0.2501.794 1.344 0.971 0.412 1.1001.642 0.9480.995 0.1601.065 Table 4 Predictors of mortality Hazard ratio 95% CI

551

p Value

0.004 0.017 0.067

0.001 0.006 0.425

Active smoking 2.39 Age-corrected Charlson comorbidity 1.29 index Number of medications that could cause erectile dysfunction 0.849

CI condence interval, FEV1 forced expiratory ow in 1 s

CI condence interval, GDS geriatric depression scale, FEV1 forced expiratory ow in 1 s

symptoms, and presence of a partner were independently associated with ED. Fourth, whether patients experienced ED or not, most reported a reduction or lack of sexual activity during the preceding year. Lastly, ED was not an independent risk factor for mortality. Prevalence of ED and Other Sexual Difculties in COPD The 72 % prevalence of self-reported ED in the current investigation is much greater than the 1522 % prevalence of ED reported in the large multinational population-based study of Nicolosi et al. [33]. This discrepancy cannot be attributed to differences in the age of the respondents or to the instrument used to identify sexual dysfunction. It follows that the discrepancy is likely due to COPD and comorbidities associated with COPD. A high prevalence of ED in COPD patients has been reported by Koseoglu et al. [40] (76 %) and Karadag et al. [8] (87 %). In these studies, the presence of ED was assessed using the international index of erectile function (IIEF). In contrast to the GSSAB, the IIEF provides no information on the extent of dissatisfaction with current sexual function if it had to continue for the rest of the patients life and the perceived causes of sexual inactivity during the preceding year. In addition to ED, the IIEF questionnaire is designed to gather information on orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction. Unfortunately, in the study of Karadag et al. [8] only erectile function was explored in a select group of men with COPD. Specically, the investigators excluded patients with signicant cardiovascular endocrine or metabolic disturbances. In the smaller study of Koseoglu et al. [40], results on the ve IIEF domains of sexual well-being were reported. In this second study [40], however, prevalence of hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and

Fig. 4 KaplanMeier survival curves for men with COPD with selfreported erectile dysfunction (red line) and no self-reported erectile dysfunction (blue line). Survival time was not affected by the presence of erectile dysfunction (log-rank test; p = 0.715). Censored patients are shown as small vertical blips on the survival curves

sexual dysfunction on quality of life and survival in men with COPD. The study has ve major ndings. First, as reported by other investigators [8, 40], ED was the most common sexual dysfunction experienced by men 55 years or older with COPD. Second, most patients were dissatised with their current sexual function and with the prospect that their sexual function would be the same in the future. Third, low testosterone levels, signicant depressive

123

552

Lung (2012) 190:545556

peripheral vascular disease were unusually low: 34, 19 and 2 %, respectively. In both studies, only patients with a regular sexual relationship were included. The latter inclusion criteria plus the exclusion of patients with comorbidities [8]or the unusually low incidence of comorbidities that could affect erectile function [40]and the lack of information of domains of sexual function other than erectile function [8] limit the generalization of the results of those two studies to men with COPD at large. These limitations were overcome in our study. In our investigation sexual well-being was assessed with a modied version of the GSSAB questionnaire. In addition to erectile function, the questionnaire provided information on three additional domains of sexual well-being: sexual interest, ability to climax, and judging sex pleasurable. As compared to the study of Nicolosi et al. [33], more patients in the current investigation reported lack in sexual interest (37 vs. 1316 %), inability to climax (42 vs. 1117 %), and found sex not pleasurable (28 vs. 8 %). These results suggest that all sexual domains are worse in men with COPD than in community-dwelling men of similar age [33]. An intriguing nding in the current investigation was the high prevalence of patients who considered sex pleasurable (72 %) and who reported sexual desire (63 %) despite the high prevalence of at least one sexual dysfunction (74 %), including ED (72 %). Several observations recorded in elderly community-dwelling men may shed some light into this dichotomy. First, elderly men more often complain of ED than loss of libido [18]. Second, orgasm can occur in the absence of a full erection [45]. Third, in a Swedish study of nearly 600 community-dwelling older men, over 96 % of participants had a positive attitude toward sexuality even though less than two thirds of them had sexual intercourse during the previous year [46]. Lastly, the physical act of sex (intercourse) is only one aspect of human sexuality [47]. Human sexuality is a manifestation of the desire for companionship, intimacy, care, love, as well as engagement in the physical act of sex [47], i.e., a patient may be too disabled to perform the physical act, however, he/she may still remain intimate with his/her partner [47, 48]. Impact of Sexual Dysfunctions on Quality of Life Sexual dysfunctions interfered with the patients quality of life. Specically, ED was bothersome to 76 % of our patients, and lack of sexual interest was bothersome to 58 % of our patients. The corresponding gures in a recent study of nearly 1,500 community-dwelling men were 90 and 65 % [3]. The apparent greater impact on quality of life of ED and lack of sexual interest in communitydwelling men than in men with COPD raises the possibility

that elderly men with COPD have fewer expectations associated with sexual activity than their communitydwelling counterparts. Possible reasons for the fewer expectations include the realization that respiratory symptoms are permanent [49], loss of a positive body image [47], and fear of coping with the physical aspect of sex [47]. The possibility that men with COPD have fewer expectations associated with sexual activity, however, is difcult to reconcile with the observation that 29 of the 38 patients who were unable to climax (77 %) were bothered by this limitation, a gure that is similar to that reported among community-dwelling men (73 %) [3]. The negative impact of sexual well-being on quality of life is further supported by the negative assessment patients gave when presented with the possibility of spending the rest of their lives at the current level of sexual function (Fig. 2). These observations indicate that most men with COPD desire a healthy sexual life [40] and that as with men (and women) in the general population [3, 46], the desire for a healthy sex life lasts a lifetime [3]. In addition, most patients reported a decrease in sexual activity during the previous year (Fig. 3), with a tendency for a greater decrease among patients with ED that in patients without ED (p = 0.074). The most common perceived reasons for the decreased sexual activity in both groups was the belief of being too old and/or too sick. These ndings raise two possibilities. First, ED is an important determinant of sexual activity in men with COPD. Second, the perceived physical limitation associated with the respiratory disorder is experienced as a major determinant of ED in this population of men. Stated differently, the physical limitations perceived by men with COPD force many of them to have a passive approach to sexuality or avoidance of sexuality [50]. Independent Correlates of ED As expected [6, 39], the prevalence of signicant depressive symptoms was greater among patients with ED than among patients without ED (p = 0.016) (Table 2). In addition, low testosterone levels were independently associated with ED (Table 3). The independent association between gonadal state and ED is in agreement with ndings of previous reports [913]. Central [10] and peripheral [18] actions of testosterone make a mechanistic link between low testosterone and ED biologically plausible. The presence of signicant depressive symptoms was independently associated with ED (Table 3). Several mechanisms could account for this relationship. First, depressed individuals have a tendency to self-focus and are often critical of themselves [6]. In the context of sexual relations, these attitudes may lead to performance anxiety and inability to obtain an erection. These attitudes may also

123

Lung (2012) 190:545556

553

lead to a decrease in libidoan important component of erectile response [6]. Second, depression can impair the function of the autonomic nervous system and, thus, could interfere with the (parasympathetic) relaxation of penile smooth muscle necessary for erection [6]. Third, the relationship between depression and ED could be two-way and mutually reinforcing [51]. An unexpected nding in the multivariable analysis was the independent association between availability of a partner and ED. This nding is at odds with the reported positive association between partner availability and reduced likelihood of ED in community-dwelling men [7, 43]. Patients without a partner could have overestimated their sexual prowess, i.e., without a partner a patient may not have proof whether he is capable of an erection. To avoid this confounder, we explained to patients that sex was not limited to intimacy with a partner but it also included masturbation [35]. Masturbation is a common expression of sexuality; in the investigation of Lindau et al. [3], 53 % of men aged 65-74 years who had a partner engaged in masturbation in the previous 12 months, and a similar gure (55 %) was reported for men without a partner. In addition, frequency of masturbation tends to follow the level of sexual interest [52]. In contrast, sexual activity with a partner depends on the partners willingness to engage in sexual activities and relationship characteristics [52]. Sexual activity causes an increase in cardiopulmonary load [35]. The energy expended during an orgasm is *34 metabolic equivalents (METs), which corresponds to the energy required for walking at a speed of 34 miles/h or continuously climbing stairs for 34 min [53]. Dyspnea could thus cause fear of and general anxiety about sexual activity [47]. Based on these considerations, we expected to nd an association between ED and dyspnea. Overall dyspnea scores (SOBQ) (Table 2) and dyspnea scores associated with sexual activities were similar in patients with and without ED. In addition, on multivariable analysis, overall dyspnea was not associated with ED. These observations raise the possibility of a ceiling effect of dyspnea triggered by sexual activities which possibly explains the lack of association between dyspnea and ED. A ceiling effect could also explain the lack of an independent association between ED and severity of lung disease (FEV1 % predicted) [54], the presence of comorbidities (Charlson) [3, 4, 6, 7, 42, 43], and medications [4, 6] (Table 3). All-cause Mortality and ED Contrary to our hypothesis, ED was not associated with increased mortality (Table 4). There are at least three possible explanations for this nding. First, the risk of death associated with ED is small to none. Second, the risk of death

associated with ED is age-dependent. Third, COPD and associated comorbidities increase the risk of death well beyond any possible risk associated with ED alone. The possibility that ED has little to no association with mortality is not supported by laboratory and clinical observations [22, 23, 25, 55]. First, in most older patients ED is caused by a local vascular disorder [20, 22, 23] characterized by impairment of the vasodilating nitric oxide pathway (early phase of erection) and structural vascular abnormalities (late phase of erection) [23]. Such phenomena are similar to those that cause atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [23]. Second, epidemiologic investigations support an association between ED and cardiovascular disease [22, 23, 29]. These laboratory [23] and epidemiologic [22, 23, 29] observations support a mechanistic link between ED and increased risk of allcause mortality [25], mainly through an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality [25, 55]. The possibility that the risk of death associated with ED is age-dependent is supported by the observations of Inman et al. [29]. These investigators reported that among 1,400 community-dwelling men, the presence of ED increased the risk of new-incident coronary artery disease only in men younger than 60 years and not in those older than 6070 years [29]. The mean age of the patients in our study was 69 years (Table 2). The advanced age of our patients together with the nding of Inman et al. [29] could explain why ED was not an independent risk factor for mortality in our study. Third, COPD and its associated comorbidities increase the risk of death well beyond the effect due to the association of ED with vascular disease. This possibility is supported by at least two observations. First, the incidence of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among patients with COPD is increased [26, 27]. Second, we recorded an independent association between mortality and FEV1 % predicteda nding conrming previous investigations [44]and between mortality and age-corrected Charlson score (Table 4). Critique of Methods Used The presence of ED was based on a single question (patient self-report). Several considerations lend support to our strategy. First, the single-question method can identify men with ED as accurately as a standard urologic examination [56]. Second, we did not measure nocturnal penile tumescence. Tumescence measurements, however, correlate only weakly with self-reported ED [5759]. That is, our ndings reect our focus on perception of ED and sexual well-being in general rather than on capacity. Third, self-report techniques are widely used to estimate the prevalence of sexual dysfunction [8, 33, 40, 60]. Fourth, our ndings are

123

554

Lung (2012) 190:545556 MD. Available at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/resources/docs/chtbook.htm (Accessed 15 January 2012) Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR (2001) Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:724731 Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, OMuircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ (2007) A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 357:762774 Schouten BW, Bohnen AM, Dohle GR, Groeneveld FP, Willemsen S, Thomas S, Bosch JL (2009) Risk factors for deterioration of erectile function: the Krimpen study. Int J Androl 32:166175 Rhoden EL, Teloken C, Mafessoni R, Souto CA (2002) Is there any relation between serum levels of total testosterone and the severity of erectile dysfunction? Int J Impot Res 14:167171 Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB (1998) The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: cross-sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosom Med 60:458465 Kupelian V, Shabsigh R, Travison TG, Page ST, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB (2006) Is there a relationship between sex hormones and erectile dysfunction? Results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol 176:25842588 Karadag F, Ozcan H, Karul AB, Ceylan E, Cildag O (2007) Correlates of erectile dysfunction in moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Respirology 12:248253 Svartberg J, Aasebo U, Hjalmarsen A, Sundsfjord J, Jorde R (2004) Testosterone treatment improves body composition and sexual function in men with COPD, in a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Respir Med 98:906913 Redoute J, Stoleru S, Pugeat M, Costes N, Lavenne F, Le Bars D, Dechaud H, Cinotti L, Pujol JF (2005) Brain processing of visual sexual stimuli in treated and untreated hypogonadal patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology 30:461482 Semple PD, Brown TM, Beastall GH, Semple CG (1983) Sexual dysfunction and erectile impotence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 83:587588 Aasebo U, Gyltnes A, Bremnes RM, Aakvaag A, Slordal L (1993) Reversal of sexual impotence in male patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypoxemia with longterm oxygen therapy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 46:799803 Semple PD, Beastall GH, Brown TM, Stirling KW, Mills RJ, Watson WS (1984) Sex hormone suppression and sexual impotence in hypoxic pulmonary brosis. Thorax 39:4651 Clark AS, MacLusky NJ, Goldman-Rakic PS (1988) Androgen binding and metabolism in the cerebral cortex of the developing rhesus monkey. Endocrinology 123:932940 Lugg JA, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF (1995) Dihydrotestosterone is the active androgen in the maintenance of nitric oxide-mediated penile erection in the rat. Endocrinology 136:14951501 Morelli A, Filippi S, Mancina R, Luconi M, Vignozzi L, Marini M, Orlando C, Vannelli GB, Aversa A, Natali A, Forti G, Giorgi M, Jannini EA, Ledda F, Maggi M (2004) Androgens regulate phosphodiesterase type 5 expression and functional activity in corpora cavernosa. Endocrinology 145:22532263 Mills TM, Reilly CM, Lewis RW (1996) Androgens and penile erection: a review. J Androl 17:633638 Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Gianfrilli D, Greco EA, Bonifacio V, Aversa A, Isidori A, Fabbri A, Lenzi A (2005) Effects of testosterone on sexual function in men: results of a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63:381394 Laghi F, Antonescu-Turcu A, Collins E, Segal J, Tobin DE, Jubran A, Tobin MJ (2005) Hypogonadism in men with chronic

consistent with previous data showing a prevalence of ED of 7687 % among men with COPD [8, 40]. A larger sample would have made our conclusions on mortality more robust. The overlap between the Kaplan Meier survival curves of men with and without ED (Fig. 4), however, suggests that a type 2 error was an unlikely cause for the similar mortality rates in the two groups of patients. This observation raises the consideration that future larger studies will likely support our exploratory observation on the absent effect of ED on mortality in older men with COPD. By study design, only men with COPD were enrolled. Thus, our results are not generalizable to women. Clinical Implications The effect of testosterone replacement on sexuality in older men has not been adequately investigated [18, 61]. It has been suggested that testosterone supplements might improve sexual function in men who exhibit low and lownormal testosterone levels, particularly in men failing phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, and that those positive effects on sexual function decline over time [18]. The value of testosterone treatment in older men with COPD remains to be demonstrated [9, 62]. The issue is more than a theoretical concern: erections can occur in hypogonadal men [63]. Long-term testosterone supplementation can cause side effects, including increased risk of cardiovascular adverse events [64], polycythemia, sleep apnea, and prostatic hypertrophy [62]. Long-term effects of testosterone supplementation on the risk of prostate cancer remain unknown [62]. In conclusion, in this prospective cross-sectional study, sexual dysfunctions, including ED, were common in men with COPD who were 55 years or older. These dysfunctions interfered with quality of life. In these patients, the presence of ED was not associated with increased mortality.

Acknowledgments This work was supported in part by grants from AMVETS and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Ofce of Research and Development Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. Conict of interest Eileen G. Collins, Sahar Halabi, Mathew Langston, Timothy Schnell, Martin Tobin, and Franco Laghi have no conicts of interest of nancial ties to disclose.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

References

1. NHLBI (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute). Morbidity and Mortality 2009 Chartbook on Cardiovascular, Lung, and Blood Diseases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda,

18.

19.

123

Lung (2012) 190:545556 obstructive pulmonary disease: prevalence and quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171:728733 Slag MF, Morley JE, Elson MK, Trence DL, Nelson CJ, Nelson AE, Kinlaw WB, Beyer HS, Nuttall FQ, Shafer RB (1983) Impotence in medical clinic outpatients. JAMA 249:17361740 Melman A, Gingell JC (1999) The epidemiology and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. J Urol 161:511 Meldrum DR, Gambone JC, Morris MA, Meldrum DA, Esposito K, Ignarro LJ (2011) The link between erectile and cardiovascular health: the canary in the coal mine. Am J Cardiol 108(4):599606 Miner MM (2011) Erectile dysfunction: a harbinger or consequence: does its detection lead to a window of curability? J Androl 32:125134 Solomon H, Man JW, Jackson G (2003) Erectile dysfunction and the cardiovascular patient: endothelial dysfunction is the common denominator. Heart 89:251253 Araujo AB, Travison TG, Ganz P, Chiu GR, Kupelian V, Rosen RC, Hall SA, McKinlay JB (2009) Erectile dysfunction and mortality. J Sex Med 6:24452454 Curkendall SM, Lanes S, de Luise C, Stang MR, Jones JK, She D, Goehring E Jr (2006) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and cardiovascular outcomes. Eur J Epidemiol 21:803813 Mannino DM, Thorn D, Swensen A, Holguin F (2008) Prevalence and outcomes of diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease in COPD. Eur Respir J 32:962969 Laumann EO, Paik A, Glasser DB, Kang JH, Wang T, Levinson B, Moreira ED Jr, Nicolosi A, Gingell C (2006) A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: ndings from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Arch Sex Behav 35:145161 Inman BA, Sauver JL, Jacobson DJ, McGree ME, Nehra A, Lieber MM, Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ (2009) A population-based, longitudinal study of erectile dysfunction and future coronary artery disease. Mayo Clin Proc 84:108113 Halabi S, Collins E, Thorevska N, Tobin MJ, Laghi F (2011) Relationship between depressive symptoms and hypogonadism in men with COPD. COPD 8:346353 Collins EG, Langbein WE, Fehr L, OConnell S, Jelinek C, Hagarty E, Edwards L, Reda D, Tobin MJ, Laghi F (2008) Can ventilation-feedback training augment exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 177:844852 Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J (1994) Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 47:12451251 Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Moreira ED Jr, Paik A, Gingell C (2004) Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology 64:991997 Stewart AL, Ware JE (1992) Measuring Functioning and WellBeing: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Duke University Press, Durham Schonhofer B, Von Sydow K, Bucher T, Nietsch M, Suchi S, Kohler D, Jones PW (2001) Sexuality in patients with noninvasive mechanical ventilation due to chronic respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164:16121617 Eakin EG, Resnikoff PM, Prewitt LM, Ries AL, Kaplan RM (1998) Validation of a new dyspnea measure: the UCSD shortness of breath questionnaire. University of California, San Diego. Chest 113:619624 Peach J, Koob JJ, Kraus MJ (2001) Psychometric evaluation of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): supporting its use in health care settings. Clin Gerontol 23:5768 Salameh WA, Redor-Goldman MM, Clarke NJ, Reitz RE, Cauleld MP (2010) Validation of a total testosterone assay using

555 high-turbulence liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: total and free testosterone reference ranges. Steroids 75:169175 Rosen RC, Seidman SN, Menza MA, Shabsigh R, Roose SP, Tseng LJ, Orazem J, Siegel RL (2004) Quality of life, mood, and sexual function: a path analytic model of treatment effects in men with erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms. Int J Impot Res 16:334340 Koseoglu N, Koseoglu H, Ceylan E, Cimrin HA, Ozalevli S, Esen A (2005) Erectile dysfunction prevalence and sexual function status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Urol 174:249252 Fletcher EC, Martin RJ (1982) Sexual dysfunction and erectile impotence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 81:413421 Wu C, Zhang H, Gao Y, Tan A, Yang X, Lu Z, Zhang Y, Liao M, Wang M, Mo Z (2012) The association of smoking and erectile dysfunction: results from the Fangchenggang Area Male Health and Examination Survey (FAMHES). J Androl 33(1):5965 Nicolosi A, Moreira ED Jr, Shirai M, Bin Mohd Tambi MI, Glasser DB (2003) Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction in four countries: cross-national study of the prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction. Urology 61:201206 Marquis K, Debigare R, Lacasse Y, LeBlanc P, Jobin J, Carrier G, Maltais F (2002) Midthigh muscle cross-sectional area is a better predictor of mortality than body mass index in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:809813 Paduch DA, Bolyakov A, Beardsworth A, Watts SD (2012) Factors associated with ejaculatory and orgasmic dysfunction in men with erectile dysfunction: analysis of clinical trials involving the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor tadalal. BJU Int 109:10601067 Beckman N, Waern M, Gustafson D, Skoog I (2008) Secular trends in self reported sexual activity and satisfaction in Swedish 70 year olds: cross sectional survey of four populations, 19712001. BMJ 337:a279 Vincent EE, Singh SJ (2007) Review article: addressing the sexual health of patients with COPD: the needs of the patient and implications for health care professionals. Chron Respir Dis 4:111115 Stannek T, Hurny C, Schoch OD, Bucher T, Munzer T (2009) Factors affecting self-reported sexuality in men with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Sex Med 6:34153424 Kaptein AA, van Klink RC, de Kok F, Scharloo M, Snoei L, Broadbent E, Bel EH, Rabe KF (2008) Sexuality in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med 102:198204 Timms RM (1982) Sexual dysfunction and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 81:398400 Perelman MA (2011) Erectile dysfunction and depression: screening and treatment. Urol Clin North Am 38:125139 Bancroft J (2005) The endocrinology of sexual arousal. J Endocrinol 186:411427 Thorson AI (2003) Sexual activity and the cardiac patient. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 12:3840 Ibanez M, Aguilar JJ, Maderal MA, Prats E, Farrero E, Font A, Escarrabill J (2001) Sexuality in chronic respiratory failure: coincidences and divergences between patient and primary caregiver. Respir Med 95:975979 Schouten BW, Bohnen AM, Bosch JL, Bernsen RM, Deckers JW, Dohle GR, Thomas S (2008) Erectile dysfunction prospectively associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population: results from the Krimpen Study. Int J Impot Res 20:9299 ODonnell AB, Araujo AB, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB (2005) The validity of a single-question self-report of erectile dysfunction.

20.

39.

21. 22.

40.

23.

41.

24.

42.

25.

43.

26.

44.

27.

28.

45.

29.

46.

30.

47.

31.

48.

32. 33.

49.

50. 51. 52. 53. 54.

34.

35.

36.

55.

37.

38.

56.

123

556 Results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Gen Intern Med 20:515519 Melman A, Fogarty J, Hafron J (2006) Can self-administered questionnaires supplant objective testing of erectile function? A comparison between the International Index of Erectile Function and objective studies. Int J Impot Res 18:126129 Yang CC, Porter MP, Penson DF (2006) Comparison of the International Index of Erectile Function erectile domain scores and nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity measurements: does one predict the other? BJU Int 98:105109 Wu CJ, Hsieh JT, Lin JS, Hwang TI, Jiann BP, Huang ST, Wang CJ, Lee SS, Chiang HS, Chen KK, Lin HD (2007) Comparison of prevalence between self-reported erectile dysfunction and erectile dysfunction as dened by ve-item International Index of Erectile Function in Taiwanese men older than 40 years. Urology 69:743747 De Berardis G, Franciosi M, Belglio M, Di Nardo B, Greeneld S, Kaplan SH, Pellegrini F, Sacco M, Tognoni G, Valentini M,

Lung (2012) 190:545556 Nicolucci A (2002) Erectile dysfunction and quality of life in type 2 diabetic patients: a serious problem too often overlooked. Diabetes Care 25:284291 Liverman CT, Blazer DG (eds) (2004) Future research directions. In: Testosterone and aging: clinical research directions. Washington, DC: The National Academic Press, pp 112158 Laghi F, Adiguzel N, Tobin MJ (2009) Endocrinological derangements in COPD. Eur Respir J 34:975996 Soran H, Wu FC (2005) Endocrine causes of erectile dysfunction. Int J Androl 28(Suppl 2):2834 Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, Storer TW, Farwell WR, Jette AM, Eder R, Tennstedt S, Ulloor J, Zhang A, Choong K, Lakshman KM, Mazer NA, Miciek R, Krasnoff J, Elmi A, Knapp PE, Brooks B, Appleman E, Aggarwal S, Bhasin G, Hede-Brierley L, Bhatia A, Collins L, LeBrasseur N, Fiore LD, Bhasin S (2010) Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med 363:109122

57.

61.

58.

62. 63. 64.

59.

60.

123

Copyright of Lung is the property of Springer Science & Business Media B.V. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Вам также может понравиться

- Analysis: Managing Mental Health Challenges Faced by Healthcare Workers During Covid-19 PandemicДокумент4 страницыAnalysis: Managing Mental Health Challenges Faced by Healthcare Workers During Covid-19 PandemicFahimul Hoque JisanОценок пока нет

- Atención de Salud Mental para El Personal Médico en China Durante El Brote de COVID-19Документ2 страницыAtención de Salud Mental para El Personal Médico en China Durante El Brote de COVID-19Christian PinoОценок пока нет

- Public Mental Health Crisis During COVID-19 Pandemic, China PDFДокумент10 страницPublic Mental Health Crisis During COVID-19 Pandemic, China PDFMauricio FonsecaОценок пока нет

- Self-Care in The ContextДокумент80 страницSelf-Care in The Contextleafar78Оценок пока нет

- Sex 2Документ13 страницSex 2leafar78Оценок пока нет

- Psychological Interventions For People Affected by The COVID-19 Epidemic PDFДокумент3 страницыPsychological Interventions For People Affected by The COVID-19 Epidemic PDFJoel IbarraОценок пока нет

- Home Sweet HomeДокумент8 страницHome Sweet Homeleafar78Оценок пока нет

- Experiences of Health-Promoting Self-CareДокумент10 страницExperiences of Health-Promoting Self-Careleafar78Оценок пока нет

- A Place of Ones' OwnДокумент6 страницA Place of Ones' Ownleafar78Оценок пока нет

- Mac 4Документ18 страницMac 4leafar78Оценок пока нет

- Mac 2Документ10 страницMac 2leafar78Оценок пока нет

- Mac 3Документ9 страницMac 3leafar78Оценок пока нет

- Self-Care Strategies UsedДокумент10 страницSelf-Care Strategies Usedleafar78Оценок пока нет

- Newman The Focus of The Discipline Revisited.11Документ12 страницNewman The Focus of The Discipline Revisited.11leafar78Оценок пока нет

- Mac 2Документ10 страницMac 2leafar78Оценок пока нет

- Holding On: Background and SignificanceДокумент9 страницHolding On: Background and Significanceleafar78Оценок пока нет

- Self-Care Activity As A StructureДокумент7 страницSelf-Care Activity As A Structureleafar78Оценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Clinical Practice: History SubtypesДокумент6 страницClinical Practice: History SubtypesRafael Alejandro Marín GuzmánОценок пока нет

- List of AntibioticsДокумент9 страницList of Antibioticsdesi_mОценок пока нет

- Prescription AnalysisДокумент16 страницPrescription AnalysisMohd Azfar HafizОценок пока нет

- Hepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)Документ2 страницыHepatopulmonary Syndrome (HPS)Cristian urrutia castilloОценок пока нет

- 04 Hemoglobin ThalassemiasДокумент37 страниц04 Hemoglobin ThalassemiasBianca Ocampo100% (1)

- BATHE Journal PDFДокумент10 страницBATHE Journal PDFKAROMAHUL MALAYA JATIОценок пока нет

- SilosДокумент3 страницыSilosapi-548205221100% (1)

- Common Oral Lesions: Aphthous Ulceration, Geographic Tongue, Herpetic GingivostomatitisДокумент13 страницCommon Oral Lesions: Aphthous Ulceration, Geographic Tongue, Herpetic GingivostomatitisFaridaFoulyОценок пока нет

- First Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in HospitalizedДокумент35 страницFirst Diagnosis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in HospitalizedFranco PacelloОценок пока нет

- Review of Acrylic Removable Partial DenturesДокумент64 страницыReview of Acrylic Removable Partial Denturesasop060% (1)

- The Life Changing Effects of Magic Mushrooms and Why The Government Keeps This From YouДокумент4 страницыThe Life Changing Effects of Magic Mushrooms and Why The Government Keeps This From YouMircea Cristian Peres100% (1)

- Registered Pharmacist Affidavit FormatДокумент1 страницаRegistered Pharmacist Affidavit FormatSyed NawazОценок пока нет

- Taklimat Perubatan Forensik - PENGENALANДокумент62 страницыTaklimat Perubatan Forensik - PENGENALANzahariОценок пока нет

- The PrescriptionДокумент86 страницThe PrescriptionChristine Arrabis100% (3)

- Medical Auditing Training: CPMA®: Practical Application WorkbookДокумент16 страницMedical Auditing Training: CPMA®: Practical Application WorkbookAnthony El HageОценок пока нет

- Why Advocate Re RedcopДокумент34 страницыWhy Advocate Re RedcopnichiichaiiОценок пока нет

- O&G Off-Tag Assesment Logbook: Traces-Pdf-248732173Документ9 страницO&G Off-Tag Assesment Logbook: Traces-Pdf-248732173niwasОценок пока нет

- Prisma 2021Документ10 страницPrisma 2021Quispe RoyОценок пока нет

- 2008 Polyflux R Spec Sheet - 306150076 - HДокумент2 страницы2008 Polyflux R Spec Sheet - 306150076 - HMehtab AhmedОценок пока нет

- Reduction of Risk Sensory Perception Mobility RationalesДокумент10 страницReduction of Risk Sensory Perception Mobility Rationalesrhymes2u100% (3)

- Epilepsy Sa 1Документ33 страницыEpilepsy Sa 1Kishan GoyaniОценок пока нет

- Unit Assessments, Rubrics, and ActivitiesДокумент15 страницUnit Assessments, Rubrics, and Activitiesjaclyn711Оценок пока нет

- Assessing The Nails: Return Demonstration Tool Evaluation ForДокумент2 страницыAssessing The Nails: Return Demonstration Tool Evaluation ForAlexandra DelizoОценок пока нет

- Format OpnameДокумент21 страницаFormat OpnamerestutiyanaОценок пока нет

- Vaccine Card - 20231120 - 175739 - 0000Документ2 страницыVaccine Card - 20231120 - 175739 - 0000MarilynОценок пока нет

- Epidural AnalgesiaДокумент16 страницEpidural AnalgesiaspreeasОценок пока нет

- PHARMA - Module 7Документ1 страницаPHARMA - Module 7Ashley AmihanОценок пока нет

- Kraeplin - Dementia Praecox and ParaphreniasДокумент356 страницKraeplin - Dementia Praecox and ParaphreniasHayanna Silva100% (1)

- Product Name:: Alaris™ GS, GH, CC, TIVA, PK, Enteral Syringe PumpДокумент14 страницProduct Name:: Alaris™ GS, GH, CC, TIVA, PK, Enteral Syringe PumpSalim AloneОценок пока нет

- Minutes of Meeting November 2020Документ2 страницыMinutes of Meeting November 2020Jonella Anne CastroОценок пока нет