Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Full Text Set 4 VVV

Загружено:

Basri JayОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Full Text Set 4 VVV

Загружено:

Basri JayАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

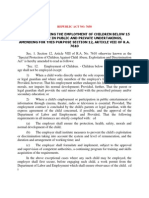

G.R. No.

L-6913

November 21, 1913

THE ROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF JARO, plaintiff-appellee, vs. GREGORIO DE LA PEA, administrator of the estate of Father Agustin de la Pea, defendantappellant. J. Lopez Arroyo and Horrilleno, for appellee. Vito, for appellant.

MORELAND, J.: This is an appeal by the defendant from a judgment of the Court of First Instance of Iloilo, awarding to the plaintiff the sum of P6,641, with interest at the legal rate from the beginning of the action. It is established in this case that the plaintiff is the trustee of a charitable bequest made for the construction of a leper hospital and that father Agustin de la Pea was the duly authorized representative of the plaintiff to receive the legacy. The defendant is the administrator of the estate of Father De la Pea. In the year 1898 the books Father De la Pea, as trustee, showed that he had on hand as such trustee the sum of P6,641, collected by him for the charitable purposes aforesaid. In the same year he deposited in his personal account P19,000 in the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank at Iloilo. Shortly thereafter and during the war of the revolution, Father De la Pea was arrested by the military authorities as a political prisoner, and while thus detained made an order on said bank in favor of the United States Army officer under whose charge he then was for the sum thus deposited in said bank. The arrest of Father De la Pea and the confiscation of the funds in the bank were the result of the claim of the military authorities that he was an insurgent and that the funds thus deposited had been collected by him for revolutionary purposes. The money was taken from the bank by the military authorities by virtue of such order, was confiscated and turned over to the Government. While there is considerable dispute in the case over the question whether the P6,641 of trust funds was included in the P19,000 deposited as aforesaid, nevertheless, a careful examination of the case leads us to the conclusion that said trust funds were a part of the funds deposited and which were removed and confiscated by the military authorities of the United States. That branch of the law known in England and America as the law of trusts had no exact counterpart in the Roman law and has none under the Spanish law. In this jurisdiction, therefore, Father De la Pea's liability is determined by those portions of the Civil Code which relate to obligations. (Book 4, Title 1.) Although the Civil Code states that "a person obliged to give something is also bound to preserve it with the diligence pertaining to a good father of a family" (art. 1094), it also provides, following the principle of the Roman law, major casus est, cui humana infirmitas resistere non potest, that "no one shall be liable for events which could not be foreseen, or which having been foreseen were inevitable, with the exception of the cases expressly mentioned in the law or those in which the obligation so declares." (Art. 1105.) By placing the money in the bank and mixing it with his personal funds De la Pea did not thereby assume an obligation different from that under which he would have lain if such deposit had not been made, nor did he thereby make himself liable to repay the money at all hazards. If the had been forcibly taken from his pocket or from his house by the military forces of one of the combatants during a state of war, it is clear that under the provisions of the Civil Code he would have been exempt from responsibility.

The fact that he placed the trust fund in the bank in his personal account does not add to his responsibility. Such deposit did not make him a debtor who must respond at all hazards. We do not enter into a discussion for the purpose of determining whether he acted more or less negligently by depositing the money in the bank than he would if he had left it in his home; or whether he was more or less negligent by depositing the money in his personal account than he would have been if he had deposited it in a separate account as trustee. We regard such discussion as substantially fruitless, inasmuch as the precise question is not one of negligence. There was no law prohibiting him from depositing it as he did and there was no law which changed his responsibility be reason of the deposit. While it may be true that one who is under obligation to do or give a thing is in duty bound, when he sees events approaching the results of which will be dangerous to his trust, to take all reasonable means and measures to escape or, if unavoidable, to temper the effects of those events, we do not feel constrained to hold that, in choosing between two means equally legal, he is culpably negligent in selecting one whereas he would not have been if he had selected the other. The court, therefore, finds and declares that the money which is the subject matter of this action was deposited by Father De la Pea in the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation of Iloilo; that said money was forcibly taken from the bank by the armed forces of the United States during the war of the insurrection; and that said Father De la Pea was not responsible for its loss. The judgment is therefore reversed, and it is decreed that the plaintiff shall take nothing by his complaint. Arellano, C.J., Torres and Carson, JJ., concur.

G.R. No. 4015

August 24, 1908 JAVELLANA, plaintiff-appellee,

ANGEL vs. JOSE LIM, ET AL., defendants-appellants. R. B. Montinola for appellee. TORRES, J.: Zaldarriaga for

appellants.

The attorney for the plaintiff, Angel Javellana, file a complaint on the 30th of October, 1906, with the Court of First Instance of Iloilo, praying that the defendants, Jose Lim and Ceferino Domingo Lim, he sentenced to jointly and severally pay the sum of P2,686.58, with interest thereon at the rate of 15 per cent per annum from the 20th of January, 1898, until full payment should be made, deducting from the amount of interest due the sum of P1,102.16, and to pay the costs of the proceedings. Authority from the court having been previously obtained, the complaint was amended on the 10th of January, 1907; it was then alleged, on the 26th of May, 1897, the defendants executed and subscribed a document in favor of the plaintiff reading as follows: We have received from Angel Javellana, as a deposit without interest, the sum of two thousand six hundred and eighty-six cents of pesos fuertes, which we will return to the said gentleman, jointly and severally, on the 20th of January, 1898. Jaro, 26th of May, 1897. Signed Jose Lim. Signed: Ceferino Domingo Lim.

That, when the obligation became due, the defendants begged the plaintiff for an extension of time for the payment thereof, building themselves to pay interest at the rate of 15 per cent on the amount of their indebtedness, to which the plaintiff acceded; that on the 15th of May, 1902, the debtors paid on account of interest due the sum of P1,000 pesos, with the exception of either capital or interest, had thereby been subjected to loss and damages. A demurrer to the original complaint was overruled, and on the 4th of January, 1907, the defendants answered the original complaint before its amendment, setting forth that they acknowledged the facts stated in Nos. 1 and 2 of the complaint; that they admitted the statements of the plaintiff relative to the payment of 1,102.16 pesos made on the 15th of November, 1902, not, however, as payment of interest on the amount stated in the foregoing document, but on account of the principal, and denied that there had been any agreement as to an extension of the time for payment and the payment of interest at the rate of 15 per cent per annum as alleged in paragraph 3 of the complaint, and also denied all the other statements contained therein. As a counterclaim, the defendants alleged that they had paid to the plaintiff sums which, together with the P1,102.16 acknowledged in the complaint, aggregated the total sum of P5,602.16, and that, deducting therefrom the total sum of P2,686.58 stated in the document transcribed in the complaint, the plaintiff still owed the defendants P2,915.58; therefore, they asked that judgment be entered absolving them, and sentencing the plaintiff to pay them the sum of P2,915.58 with the costs. Evidence was adduced by both parties and, upon their exhibits, together with an account book having been made of record, the court below rendered judgment on the 15th of January, 1907, in favor of the plaintiff for the recovery of the sum of P5,714.44 and costs. The defendants excepted to the above decision and moved for a new trial. This motion was overruled and was also excepted to by them; the bill of exceptions presented by the appellants having been approved, the same was in due course submitted to this court. The document of indebtedness inserted in the complaint states that the plaintiff left on deposit with the defendants a given sum of money which they were jointly and severally obliged to return on a certain date fixed in the document; but that, nevertheless, when the document appearing as Exhibits 2, written in the Visayan dialect and followed by a translation into Spanish was executed, it was acknowledged, at the date thereof, the 15th of November, 1902, that the amount deposited had not yet been returned to the creditor, whereby he was subjected to losses and damages amounting to 830 pesos since the 20th of January, 1898, when the return was again stipulated with the further agreement that the amount deposited should bear interest at the rate of 15 per cent per annum, from the aforesaid date of January 20, and that the 1,000 pesos paid to the depositor on the 15th of May, 1900, according to the receipt issued by him to the debtors, would be included, and that the said rate of interest would obtain until the debtors on the 20th of May, 1897, it is called a deposit consisted, and they could have accomplished the return agreed upon by the delivery of a sum equal to the one received by them. For this reason it must be understood that the debtors were lawfully authorized to make use of the amount deposited, which they have done, as subsequent shown when asking for an extension of the time for the return thereof, inasmuch as, acknowledging that they have subjected the letter, their creditor, to losses and damages for not complying with what had been stipulated, and being conscious that they had used, for their own profit and gain, the money that they received apparently as a deposit, they engaged to pay interest to the creditor from the date named until the time when the refund should be made. Such conduct on the part of the debtors is unquestionable evidence that the transaction entered into between the interested parties was not a deposit, but a real contract of loan. Article 1767 of the Civil Code provides that The depository can not make use of the thing deposited without the express permission of the depositor.

Otherwise he shall be liable for losses and damages. Article 1768 also provides that When the depository has permission to make use of the thing deposited, the contract loses the character of a deposit and becomes a loan or bailment. The permission shall not be presumed, and its existence must be proven. When on one of the latter days of January, 1898, Jose Lim went to the office of the creditor asking for an extension of one year, in view of the fact the money was scare, and because neither himself nor the other defendant were able to return the amount deposited, for which reason he agreed to pay interest at the rate of 15 per cent per annum, it was because, as a matter of fact, he did not have in his possession the amount deposited, he having made use of the same in his business and for his own profit; and the creditor, by granting them the extension, evidently confirmed the express permission previously given to use and dispose of the amount stated as having bee deposited, which, in accordance with the loan, to all intents and purposes gratuitously, until the 20th of January, 1898, and from that dated with interest at 15 per cent per annum until its full payment, deducting from the total amount of interest the sum of 1,000 pesos, in accordance with the provisions of article 1173 of the Civil Code. Notwithstanding that it does not appear that Jose Lim signed the document (Exhibit 2) executed in the presence of three witnesses on the 15th of November, 1902, by Ceferino Domingo Lim on behalf of himself and the former, nevertheless, the said document has not been contested as false, either by a criminal or by a civil proceeding, nor has any doubt been cast upon the authenticity of the signatures of the witnesses who attested the execution of the same; and from the evidence in the case one is sufficiently convinced that the said Jose Lim was perfectly aware of and authorized his joint codebtor to liquidate the interest, to pay the sum of 1,000 pesos, on account thereof, and to execute the aforesaid document No. 2. A true ratification of the original document of deposit was thus made, and not the least proof is shown in the record that Jose Lim had ever paid the whole or any part of the capital stated in the original document, Exhibit 1. If the amount, together with interest claimed in the complaint, less 1,000 pesos appears as fully established, such is not the case with the defendant's counterclaim for P5,602.16, because the existence and certainty of said indebtedness imputed to the plaintiff has not been proven, and the defendants, who call themselves creditors for the said amount have not proven in a satisfactory manner that the plaintiff had received partial payments on account of the same; the latter alleges with good reason, that they should produce the receipts which he may have issued, and which he did issue whenever they paid him any money on account. The plaintiffs allegation that the two amounts of 400 and 1,200 pesos, referred to in documents marked "C" and "D" offered in evidence by the defendants, had been received from Ceferino Domingo Lim on account of other debts of his, has not been contradicted, and the fact that in the original complaint the sum of 1,102.16 pesos, was expressed in lieu of 1,000 pesos, the only payment made on account of interest on the amount deposited according to documents No. 2 and letter "B" above referred to, was due to a mistake. Moreover, for the reason above set forth it may, as a matter of course, be inferred that there was no renewal of the contract deposited converted into a loan, because, as has already been stated, the defendants received said amount by virtue of real loan contract under the name of a deposit, since the so-called bailees were forthwith authorized to dispose of the amount deposited. This they have done, as has been clearly shown. The original joint obligation contracted by the defendant debtor still exists, and it has not been shown or proven in the proceedings that the creditor had released Joe Lim from complying with his obligation in order that he should not be sued for or sentenced to pay the amount of capital and interest together with his codebtor, Ceferino Domingo Lim, because the record offers satisfactory evidence against the

pretension of Jose Lim, and it further appears that document No. 2 was executed by the other debtor, Ceferino Domingo Lim, for himself and on behalf of Jose Lim; and it has also been proven that Jose Lim, being fully aware that his debt had not yet been settled, took steps to secure an extension of the time for payment, and consented to pay interest in return for the concession requested from the creditor. In view of the foregoing, and adopting the findings in the judgment appealed from, it is our opinion that the same should be and is hereby affirmed with the costs of this instance against the appellant, provided that the interest agreed upon shall be paid until the complete liquidation of the debt. So ordered. Arellano, C.J., Carson, Willard and Tracey, JJ., concur. G.R. No. L-7097 October 23, 1912

VICENTE DELGADO, defendant-appellee, vs. PEDRO BONNEVIE and FRANCISCO ARANDEZ, plaintiffs-appellants. O' Brien and DeWitt, Roco and Roco, for appellee. and A. V. Herrero, for appellants.

ARELLANO, C.J.: When Pedro Bonnevie and Francisco Arandez formed in Nueva Caceres, Ambos Camarines, a regular general partnership for engaging in the business of threshing paddy, Vicente Delgado undertook to deliver to them paddy for this purpose to be cleaned and returned to him as rice, with the agreement of payment them 10 centimosfor each cavan and to have returned in the rice one-half the amount received as paddy. The paddy received for this purpose was credited by receipts made out in this way: "Receipt for (number) cavanes of paddy in favor of (owner of the paddy), Nueva Caceres, (day) of (month), 1898." And they issued to Vicente Delgado receipts Nos. 86-99 for a total of 2,003 cavanes and a half of paddy, from April 9 to June 8, 1898. On February 6, 1909, Vicente Delgado appeared in the Court of First Instance of Ambos Camarines with said receipts, demanding return of the said 2,003 and a half cavanes of paddy, or in the absence thereof, of the price of said article at the rate of 3 pesos the cavan of 6,009 pesos and 50 centimos, with the interest thereon at 6 percent a year reckoning from, November 21, 905, until complete payment, and the costs. The plaintiff asked that the interest run from November 21, 1905, because on that date his counsel demanded of the defendants, Bonnevie and Arandez, their partnership having been dissolved, that they settle the accounts in this matter. The court decided the case by sentencing the defendant, Pedro Bonnevie and Francisco Arandez, to pay to Vicente Delgado two thousand seven hundred and fifty-four pesos and 81 centimos (2,754.81), the value of 2,003 cavanes of paddy at the rate of 11 reales the cavan and 6 percent interest on said sum reckoned from November 21, 1905, and the costs. On appeal to this Supreme Court, the only grounds of error assigned are: (1) Violation of articles 532 and 950 of the Code of Commerce; (2) violation of articles 309 of the Code of Commerce and 1955 and 1962 of the Civil Code; and (3) violation of section 296 of the Code of Civil Procedure. With reference to the first assignment of error it is alleged that the receipts in question, the form whereof has been set forth, were all issued before July 11, 1898, and being credit paper as defined in

paragraph 2 of article 532 of the Code of Commerce, the right of action arising therefrom prescribed before July 11, 1901, in accordance with article 950 of the Code of Commerce. This conclusion is not admissible. It is true that, according to the article 950 of the Code of Commerce, actions arising from bills of exchange, drafts, notes, checks, securities, dividends, coupons, and the amounts of the amortization of obligations issued in accordance with said code, shall extinguish three years after they have fallen due; but it is also true that as the receipts in question are not documents of any kinds enumerated in said article, the actions arising therefrom do not extinguish three years from their date (that, after all, they do not fall due). It is true that paragraph 2 of article 950 also mentions, besides those already stated, "other instruments of draft or exchange;" but it is also true that the receipts in this case are not documents of draft or exchange, they are not drafts payable to order, but they are, as the appellants acknowledge, simple promises to pay, or rather mere documents evidencing the receipt of some cavanes of paddy for the purpose already stated, which is nothing more than purely for industrial, and not for mercantile exchange. They are documents such as would be issued by the thousand socalled rice-mills scattered throughout the Islands, wherein a few poor women of the people in like manner clean the paddy by pounding it with a pestle and return hulled rice. The contract whereby one person receives from another a quantity of unhulled rice to return it hulled, for a fixed compensation or renumeration, is an industrial, not a commercial act; it is, as the appellant say, a hire of services without mercantile character, for there is nothing about the operation of washing clothes. Articles 532 and 950 of the Code of Commerce have not, therefore, been violated, for they are not applicable to the case at bar. Neither are articles 309 of the Code of Commerce and 1955 and 1962 of the Civil Code applicable. The first of these articles reads thus: Whenever, with the consent of the depositor, the depositary disposes of the articles on deposit either for himself or for his business, or for transactions intrusted to him by the former, the rights and obligations of the depositary and of the depositor shall cease, and the rules and provisions applicable to the commercial loans, commission, or contract which took place of the deposit shall be observed. The appellants say that, in accordance with this legal provision, the puddy received on deposit ceased to continue under such character in order to remain in their possession under the contract of hire of services, in virtue whereof they could change it by returning rice instead of paddy and a half less than the quantity received. They further say that the ownership of personal property, according to article 1955 of the Civil Code, prescribes by uninterrupted possession for six years, without necessity of any other condition, and in accordance with article 1962 of the same Code real actions, with regard to personal property, prescribe after the lapse of six years from the loss of possession. 1awphil.net Two questions are presented in these allegations: One regarding the nature of the obligation contracted by the appellants; and the other regarding prescription, not for a period of three years, but of six years. With reference to the first, it is acknowledged that the obligation of the appellants arose primarily out of the contract of deposit, but this deposit was later converted into a contract of hire of services, and this is true. But it is also true that, after the object of the hire of services had been fulfilled, the rice in every way remained as a deposit in the possession of the appellants for them to return to the depositor at any time they might be required to do so, and nothing has relieved them of this obligation; neither the dissolution of the partnership that united them, nor the revolutionary movement of a political character that seems to have occurred in 1898, nor the fact that they may at some time have lost possession of the rice. With reference to the second question, or under title of deposit or hire of services, the possession of the appellants can in no way amount to prescription, for the thing received on deposit or for hire of services could not prescribe, since for every prescription of ownership the possession must be in the

capacity of an owner, public, peaceful, and uninterrupted (Civil Code, 1941); and the appellants could not possess the rice in the capacity of owners, taking for granted that the depositor or lessor never could have believed that he had transferred to them ownership of the thing deposited or leased, but merely the care of the thing on deposit and the use or profit thereof; which is expressed in legal terms by saying that the possession of the depositary or of the lessee is not adverse to that of the depositor or lessor, who continues to be the owner of the thing which is merely held in trust by the depositary or lessee. In strict law, the deposit, when it is of fungible goods received by weight, number or measurement, becomes a mutual loan, by reason of the authorization which the depositary may have from the depositor to make use of the goods deposited. (Civil Code, 1768, and Code of Commerce, 309.) . But in the present case neither was there for authorization of the depositor nor did the depositaries intend to make use of the rice for their own consumption or profit; they were merely released from the obligation of returning the same thing and contracted in lieu thereof the obligation of delivering something similar to the half of it, being bound by no fixed terms, the opposite of what happens in a mutual loan, to make the delivery or return when and how it might please the depositor. In fact, it has happened that the depositaries have, with the consent of the depositor, as provided in article 309 of the Code of Commerce, disposed of the paddy "for transactions he intrusted to them," and that in lieu of the deposit there has been a hire of services, which is one entered into between the parties to the end that one should return in rice half of the quantity of paddy delivered by the other, with the obligation on the latter's part of paying 10centimos for each cavan of hulled rice. The consequence of this is that the rules and regulations for contract of hire of services must be applied to the case, one of which is that the thing must be returned after the operation entrusted and payment of compensation, and the other that the action for claiming the thing leased, being personal, does not prescribe for fifteen years under article 1964 of the Civil Code. 1awphi1.net If the action arising from the receipts in question does not prescribe in three years, as does that from bills of exchange, because they are not drafts payable to order or anything but receipts that any warehouseman would sign; if the possession of the paddy on the part of those who received it for threshing is not in the capacity of owner but only in that of depositary or lessor of services and under such character ownership thereof could not prescribe in six years, or at any time, because adverse possession and not mere holding in trust is required prescription; if the action to recover the paddy so delivered is not real with regard to personal property, possession whereof has been lost, but a personal obligation arising from contract of lease for recovery of possession that has not been lost but maintained in the lessee in the name of the lessor; if prescription of any kind can in no way be held, only because there could not have been either beginning or end of a fixed period for the prescription, it is useless to talk of interruption of the period for the prescription, to which tends the third assignment of error, wherein it is said that the court violated article 296 of the Code of Civil Procedure in admitting as proven facts not alleged in the complaint, justas if by admitting them there would have been a finding with regard to the computation of the period for timely exercise of the action, taking into consideration the legal interruptions of the running of the period of prescription. The court has made no finding in the sense that this or that period of time during which these or those facts occured must be counted out, and therefore the action has not prescribed, because by eliminating such period of time and comparing such and such date the action has been brought in due time. Prescription of three or six years cannot be presupposed in the terms alleged, but only of fifteen years, which is what is proper to oppose to the exercise of a right of action arising from hire of services and even of deposit or mutual loan, whether common or mercantile; and such is the prescription considered possible by the trial court, in conformity with articles 943 of the Code of Commerce and 1964 of the Civil Code. The trial judge confined himself to sentencing the defendants to payment of the price of the paddy, ignoring the thing itself, return whereof ought to have been the subject of judgment in the first place, because the thing itself appears to have been extinguished and its price has taken its place. But the assigning of legal interest from November 21, 1905, can have no other ground than the demand made by plaintiff's counsel upon the defendants to settle this matter. Legal interest on delinquent debts can only be

owed from the time the principal amount constitutes a clear and certain debt, and in the present case the principal debt has only been clear and certain since the date of the judgment of the lower court; so the legal interest can be owed. only since then. The judgment appealed from is affirmed, except that the legal interest shall be understood to be owed from the date thereof; with the costs of this instance against the appellants. Torres, Mapa, Johnson and Carson, JJ., concur. The preceding discussion disposes of all vital contentions relative to the liability of the defendant upon the causes of action stated in the complaints. We proceed therefore now to consider the question of the liability of the plaintiff Guillermo Baron upon the cross-complaint of Pablo David in case R. G. No. 26949. In this cross-action the defendant seek, as the stated in the third paragraph of this opinion, to recover damages for the wrongful suing out of an attachment by the plaintiff and the levy of the same upon the defendant's rice mill. It appears that about two and one-half months after said action was begun, the plaintiff, Guillermo Baron, asked for an attachment to be issued against the property of the defendant; and to procure the issuance of said writ the plaintiff made affidavit to the effect that the defendant was disposing, or attempting the plaintiff. Upon this affidavit an attachment was issued as prayed, and on March 27, 1924, it was levied upon the defendant's rice mill, and other property, real and personal. 1awph!l.net Upon attaching the property the sheriff closed the mill and placed it in the care of a deputy. Operations were not resumed until September 13, 1924, when the attachment was dissolved by an order of the court and the defendant was permitted to resume control. At the time the attachment was levied there were, in the bodega, more than 20,000 cavans of palay belonging to persons who held receipts therefor; and in order to get this grain away from the sheriff, twenty-four of the depositors found it necessary to submit third-party claims to the sheriff. When these claims were put in the sheriff notified the plaintiff that a bond in the amount of P50,000 must be given, otherwise the grain would be released. The plaintiff, being unable or unwilling to give this bond, the sheriff surrendered the palay to the claimants; but the attachment on the rice mill was maintained until September 13, as above stated, covering a period of one hundred seventy days during which the mill was idle. The ground upon which the attachment was based, as set forth in the plaintiff's affidavit was that the defendant was disposing or attempting to dispose of his property for the purpose of defrauding the plaintiff. That this allegation was false is clearly apparent, and not a word of proof has been submitted in support of the assertion. On the contrary, the defendant testified that at the time this attachment was secured he was solvent and could have paid his indebtedness to the plaintiff if judgment had been rendered against him in ordinary course. His financial conditions was of course well known to the plaintiff, who is his uncle. The defendant also states that he had not conveyed away any of his property, nor had intended to do so, for the purpose of defrauding the plaintiff. We have before us therefore a case of a baseless attachment, recklessly sued out upon a false affidavit and levied upon the defendant's property to his great and needless damage. That the act of the plaintiff in suing out the writ was wholly unjustifiable is perhaps also indicated in the circumstance that the attachment was finally dissolved upon the motion of the plaintiff himself. The defendant testified that his mill was accustomed to clean from 400 to 450 cavans of palay per day, producing 225 cavans of rice of 57 kilos each. The price charged for cleaning each cavan rice was 30 centavos. The defendant also stated that the expense of running the mill per day was from P18 to P25, and that the net profit per day on the mill was more than P40. As the mill was not accustomed to run on Sundays and holiday, we estimate that the defendant lost the profit that would have been earned on not less than one hundred forty work days. Figuring his profits at P40 per day, which would appear to be a conservative estimate, the actual net loss resulting from his failure to operate the mill during the time stated could not have been less than P5,600. The reasonableness of these figures is also indicated in the fact that the twenty-four customers who intervened with third-party claims took out of the camarin 20,000 cavans of palay, practically all of which, in the ordinary course of events, would have been milled in this plant by the defendant. And of course other grain would have found its way to this mill if it had remained open during the one hundred forty days when it was closed. But this is not all. When the attachment was dissolved and the mill again opened, the defendant found that his customers had become scattered and could not be easily gotten back. So slow, indeed, was his patronage in

returning that during the remainder of the year 1924 the defendant was able to mill scarcely more than the grain belonging to himself and his brothers; and even after the next season opened many of his old customers did not return. Several of these individuals, testifying as witnesses in this case, stated that, owing to the unpleasant experience which they had in getting back their grain from the sheriff to the mill of the defendant, though they had previously had much confidence in him. As against the defendant's proof showing the facts above stated the plaintiff submitted no evidence whatever. We are therefore constrained to hold that the defendant was damaged by the attachment to the extent of P5,600, in profits lost by the closure of the mill, and to the extent of P1,400 for injury to the good-will of his business, making a total of P7,000. For this amount the defendant must recover judgment on his cross-complaint. The trial court, in dismissing the defendant's cross-complaint for damages resulting from the wrongful suing out of the attachment, suggested that the closure of the rice mill was a mere act of the sheriff for which the plaintiff was not responsible and that the defendant might have been permitted by the sheriff to continue running the mill if he had applied to the sheriff for permission to operate it. This singular suggestion will not bear a moment's criticism. It was of course the duty of the sheriff, in levying the attachment, to take the attached property into his possession, and the closure of the mill was a natural, and even necessary, consequence of the attachment. For the damage thus inflicted upon the defendant the plaintiff is undoubtedly responsible. One feature of the cross-complaint consist in the claim of the defendant (cross-complaint) for the sum of P20,000 as damages caused to the defendant by the false and alleged malicious statements contained in the affidavit upon which the attachment was procured. The additional sum of P5,000 is also claimed as exemplary damages. It is clear that with respect to these damages the cross-action cannot be maintained, for the reason that the affidavit in question was used in course of a legal proceeding for the purpose of obtaining a legal remedy, and it is therefore privileged. But though the affidavit is not actionable as a libelous publication, this fact in no obstacle to the maintenance of an action to recover the damage resulting from the levy of the attachment. Before closing this opinion a word should be said upon the point raised in the first assignment of error of Pablo David as defendant in case R. G. No. 26949. In this connection it appears that the deposition of Guillermo Baron was presented in court as evidence and was admitted as an exhibit, without being actually read to the court. It is supposed in the assignment of error now under consideration that the deposition is not available as evidence to the plaintiff because it was not actually read out in court. This connection is not well founded. It is true that in section 364 of the Code of Civil Procedure it is said that a deposition, once taken, may be read by either party and will then be deemed the evidence of the party reading it. The use of the word "read" in this section finds its explanation of course in the American practice of trying cases for the most part before juries. When a case is thus tried the actual reading of the deposition is necessary in order that the jurymen may become acquainted with its contents. But in courts of equity, and in all courts where judges have the evidence before them for perusal at their pleasure, it is not necessary that the deposition should be actually read when presented as evidence. From what has been said it result that judgment of the court below must be modified with respect to the amounts recoverable by the respective plaintiffs in the two actions R. G. Nos. 26948 and 26949 and must be reversed in respect to the disposition of the cross-complaint interposed by the defendant in case R. G. No. 26949, with the following result: In case R. G. No. 26948 the plaintiff Silvestra Baron will recover of the Pablo David the sum of P6,227.24, with interest from November 21, 1923, the date of the filing of her complaint, and with costs. In case R. G. No. 26949 the plaintiff Guillermo Baron will recover of the defendant Pablo David the sum of P8,669.75, with interest from January 9, 1924. In the same case the defendant Pablo David, as plaintiff in the cross-complaint, will recover of Guillermo Baron the sum of P7,000, without costs. So ordered. Avancea, C.J., Johnson, Malcolm, Villamor, Romualdez and Villa-Real, JJ., concur. G.R. No. L-7593 March 27, 1913 STATES, plaintiff-appellee,

THE UNITED vs. JOSE M. IGPUARA, defendant-appellant. W. A. Kincaid, Thos. L. Hartigan, and Office of the Solicitor-General Harvey for appellee. Jose Robles

Lahesa

for

appellant.

ARELLANO, C.J.: The defendant therein is charged with the crime of estafa, for having swindled Juana Montilla and Eugenio Veraguth out of P2,498 Philippine currency, which he had take on deposit from the former to be at the latter's disposal. The document setting forth the obligation reads: We hold at the disposal of Eugenio Veraguth the sum of two thousand four hundred and ninety-eight pesos (P2,498), the balance from Juana Montilla's sugar. Iloilo, June 26, 1911, Jose Igpuara, for Ramirez and Co. The Court of First Instance of Iloilo sentenced the defendant to two years of presidio correccional, to pay Juana Montilla P2,498 Philippine currency, and in case of insolvency to subsidiary imprisonment at P2.50 per day, not to exceed one-third of the principal penalty, and the costs. The defendant appealed, alleging as errors: (1) Holding that the document executed by him was a certificate of deposit; (2) holding the existence of a deposit, without precedent transfer or delivery of the P2,498; and (3) classifying the facts in the case as the crime of estafa. A deposit is constituted from the time a person receives a thing belonging to another with the obligation of keeping and returning it. (Art. 1758, Civil Code.) That the defendant received P2,498 is a fact proven. The defendant drew up a document declaring that they remained in his possession, which he could not have said had he not received them. They remained in his possession, surely in no other sense than to take care of them, for they remained has no other purpose. They remained in the defendant's possession at the disposal of Veraguth; but on August 23 of the same year Veraguth demanded for him through a notarial instrument restitution of them, and to date he has not restored them. The appellant says: "Juana Montilla's agent voluntarily accepted the sum of P2,498 in an instrument payable on demand, and as no attempt was made to cash it until August 23, 1911, he could indorse and negotiate it like any other commercial instrument. There is no doubt that if Veraguth accepted the receipt for P2,498 it was because at that time he agreed with the defendant to consider the operation of sale on commission closed, leaving the collection of said sum until later, which sum remained as a loan payable upon presentation of the receipt." (Brief, 3 and 4.) Then, after averring the true facts: (1) that a sales commission was precedent; (2) that this commission was settled with a balance of P2,498 in favor of the principal, Juana Montilla; and (3) that this balance remained in the possession of the defendant, who drew up an instrument payable on demand, he has drawn two conclusions, both erroneous: One, that the instrument drawn up in the form of a deposit certificate could be indorsed or negotiated like any other commercial instrument; and the other, that the sum of P2,498 remained in defendant's possession as a loan. It is erroneous to assert that the certificate of deposit in question is negotiable like any other commercial instrument: First, because every commercial instrument is not negotiable; and second, because only instruments payable to order are negotiable. Hence, this instrument not being to order but to bearer, it is not negotiable. It is also erroneous to assert that sum of money set forth in said certificate is, according to it, in the defendant's possession as a loan. In a loan the lender transmits to the borrower the use of the thing lent, while in a deposit the use of the thing is not transmitted, but merely possession for its custody or safekeeping.

In order that the depositary may use or dispose oft he things deposited, the depositor's consent is required, and then: The rights and obligations of the depositary and of the depositor shall cease, and the rules and provisions applicable to commercial loans, commission, or contract which took the place of the deposit shall be observed. (Art. 309, Code of Commerce.) The defendant has shown no authorization whatsoever or the consent of the depositary for using or disposing of the P2,498, which the certificate acknowledges, or any contract entered into with the depositor to convert the deposit into a loan, commission, or other contract. That demand was not made for restitution of the sum deposited, which could have been claimed on the same or the next day after the certificate was signed, does not operate against the depositor, or signify anything except the intention not to press it. Failure to claim at once or delay for sometime in demanding restitution of the things deposited, which was immediately due, does not imply such permission to use the thing deposited as would convert the deposit into a loan. Article 408 of the Code of Commerce of 1829, previous to the one now in force, provided: The depositary of an amount of money cannot use the amount, and if he makes use of it, he shall be responsible for all damages that may accrue and shall respond to the depositor for the legal interest on the amount. Whereupon the commentators say: In this case the deposit becomes in fact a loan, as a just punishment imposed upon him who abuses the sacred nature of a deposit and as a means of preventing the desire of gain from leading him into speculations that may be disastrous to the depositor, who is much better secured while the deposit exists when he only has a personal action for recovery. According to article 548, No. 5, of the Penal Code, those who to the prejudice of another appropriate or abstract for their own use money, goods, or other personal property which they may have received as a deposit, on commission, or for administration, or for any other purpose which produces the obligation of delivering it or returning it, and deny having received it, shall suffer the penalty of the preceding article," which punishes such act as the crime of estafa. The corresponding article of the Penal Code of the Philippines in 535, No. 5. In a decision of an appeal, September 28, 1895, the principle was laid down that: "Since he commits the crime ofestafa under article 548 of the Penal Code of Spain who to another's detriment appropriates to himself or abstracts money or goods received on commission for delivery, the court rightly applied this article to the appellant, who, to the manifest detriment of the owner or owners of the securities, since he has not restored them, willfully and wrongfully disposed of them by appropriating them to himself or at least diverting them from the purpose to which he was charged to devote them." It is unquestionable that in no sense did the P2,498 which he willfully and wrongfully disposed of to the detriments of his principal, Juana Montilla, and of the depositor, Eugenio Veraguth, belong to the defendant. Likewise erroneous is the construction apparently at tempted to be given to two decisions of this Supreme Court (U. S. vs. Dominguez, 2 Phil. Rep., 580, and U. S. vs. Morales and Morco, 15 Phil. Rep., 236) as implying that what constitutes estafa is not the disposal of money deposited, but denial of having received same. In the first of said cases there was no evidence that the defendant had appropriated the grain deposited in his possession.

On the contrary, it is entirely probable that, after the departure of the defendant from Libmanan on September 20, 1898, two days after the uprising of the civil guard in Nueva Caceres, the rice was seized by the revolutionalists and appropriated to their own uses. In this connection it was held that failure to return the thing deposited was not sufficient, but that it was necessary to prove that the depositary had appropriated it to himself or diverted the deposit to his own or another's benefit. He was accused or refusing to restore, and it was held that the code does not penalize refusal to restore but denial of having received. So much for the crime of omission; now with reference to the crime of commission, it was not held in that decision that appropriation or diversion of the thing deposited would not constitute the crime of estafa. In the second of said decisions, the accused "kept none of the proceeds of the sales. Those, such as they were, he turned over to the owner;" and there being no proof of the appropriation, the agent could not be found guilty of the crime of estafa. Being in accord and the merits of the case, the judgment appealed from is affirmed, with costs. To G.R. No. L-60033 April 4, 1984 TEOFISTO GUINGONA, JR., ANTONIO I. MARTIN, and TERESITA SANTOS, petitioners, vs. THE CITY FISCAL OF MANILA, HON. JOSE B. FLAMINIANO, ASST. CITY FISCAL FELIZARDO N. LOTA and CLEMENT DAVID, respondents.

MAKASIAR, Actg. C.J.:+.wph!1 This is a petition for prohibition and injunction with a prayer for the immediate issuance of restraining order and/or writ of preliminary injunction filed by petitioners on March 26, 1982. On March 31, 1982, by virtue of a court resolution issued by this Court on the same date, a temporary restraining order was duly issued ordering the respondents, their officers, agents, representatives and/or person or persons acting upon their (respondents') orders or in their place or stead to refrain from proceeding with the preliminary investigation in Case No. 8131938 of the Office of the City Fiscal of Manila (pp. 47-48, rec.). On January 24, 1983, private respondent Clement David filed a motion to lift restraining order which was denied in the resolution of this Court dated May 18, 1983. As can be gleaned from the above, the instant petition seeks to prohibit public respondents from proceeding with the preliminary investigation of I.S. No. 81-31938, in which petitioners were charged by private respondent Clement David, with estafa and violation of Central Bank Circular No. 364 and related regulations regarding foreign exchange transactions principally, on the ground of lack of jurisdiction in that the allegations of the charged, as well as the testimony of private respondent's principal witness and the evidence through said witness, showed that petitioners' obligation is civil in nature. For purposes of brevity, We hereby adopt the antecedent facts narrated by the Solicitor General in its Comment dated June 28,1982, as follows:t.hqw On December 23,1981, private respondent David filed I.S. No. 81-31938 in the Office of the City Fiscal of Manila, which case was assigned to respondent Lota for preliminary investigation (Petition, p. 8).

In I.S. No. 81-31938, David charged petitioners (together with one Robert Marshall and the following directors of the Nation Savings and Loan Association, Inc., namely Homero Gonzales, Juan Merino, Flavio Macasaet, Victor Gomez, Jr., Perfecto Manalac, Jaime V. Paz, Paulino B. Dionisio, and one John Doe) with estafa and violation of Central Bank Circular No. 364 and related Central Bank regulations on foreign exchange transactions, allegedly committed as follows (Petition, Annex "A"):t.hqw "From March 20, 1979 to March, 1981, David invested with the Nation Savings and Loan Association, (hereinafter called NSLA) the sum of P1,145,546.20 on nine deposits, P13,531.94 on savings account deposits (jointly with his sister, Denise Kuhne), US$10,000.00 on time deposit, US$15,000.00 under a receipt and guarantee of payment and US$50,000.00 under a receipt dated June 8, 1980 (au jointly with Denise Kuhne), that David was induced into making the aforestated investments by Robert Marshall an Australian national who was allegedly a close associate of petitioner Guingona Jr., then NSLA President, petitioner Martin, then NSLA Executive Vice-President of NSLA and petitioner Santos, then NSLA General Manager; that on March 21, 1981 N LA was placed under receivership by the Central Bank, so that David filed claims therewith for his investments and those of his sister; that on July 22, 1981 David received a report from the Central Bank that only P305,821.92 of those investments were entered in the records of NSLA; that, therefore, the respondents in I.S. No. 81-31938 misappropriated the balance of the investments, at the same time violating Central Bank Circular No. 364 and related Central Bank regulations on foreign exchange transactions; that after demands, petitioner Guingona Jr. paid only P200,000.00, thereby reducing the amounts misappropriated to P959,078.14 and US$75,000.00." Petitioners, Martin and Santos, filed a joint counter-affidavit (Petition, Annex' B') in which they stated the following.t.hqw "That Martin became President of NSLA in March 1978 (after the resignation of Guingona, Jr.) and served as such until October 30, 1980, while Santos was General Manager up to November 1980; that because NSLA was urgently in need of funds and at David's insistence, his investments were treated as special- accounts with interest above the legal rate, an recorded in separate confidential documents only a portion of which were to be reported because he did not want the Australian government to tax his total earnings (nor) to know his total investments; that all transactions with David were recorded except the sum of US$15,000.00 which was a personal loan of Santos; that David's check for US$50,000.00 was cleared through Guingona, Jr.'s dollar account because NSLA did not have one, that a draft of US$30,000.00 was placed in the name of one Paz Roces because of a pending transaction with her; that the Philippine Deposit Insurance Corporation had already reimbursed David within the legal limits; that majority of the stockholders of NSLA had filed Special Proceedings No. 82-1695 in the Court of First Instance to contest its (NSLA's) closure; that after NSLA was placed under receivership, Martin executed a promissory note in David's favor and caused the transfer to him of a nine and on behalf (9 1/2) carat diamond ring with a net value of P510,000.00; and, that the liabilities of NSLA to David were civil in nature."

Petitioner, Guingona, Jr., in his counter-affidavit (Petition, Annex' C') stated the following:t.hqw "That he had no hand whatsoever in the transactions between David and NSLA since he (Guingona Jr.) had resigned as NSLA president in March 1978, or prior to those transactions; that he assumed a portion o; the liabilities of NSLA to David because of the latter's insistence that he placed his investments with NSLA because of his faith in Guingona, Jr.; that in a Promissory Note dated June 17, 1981 (Petition, Annex "D") he (Guingona, Jr.) bound himself to pay David the sums of P668.307.01 and US$37,500.00 in stated installments; that he (Guingona, Jr.) secured payment of those amounts with second mortgages over two (2) parcels of land under a deed of Second Real Estate Mortgage (Petition, Annex "E") in which it was provided that the mortgage over one (1) parcel shall be cancelled upon payment of one-half of the obligation to David; that he (Guingona, Jr.) paid P200,000.00 and tendered another P300,000.00 which David refused to accept, hence, he (Guingona, Jr.) filed Civil Case No. Q-33865 in the Court of First Instance of Rizal at Quezon City, to effect the release of the mortgage over one (1) of the two parcels of land conveyed to David under second mortgages." At the inception of the preliminary investigation before respondent Lota, petitioners moved to dismiss the charges against them for lack of jurisdiction because David's claims allegedly comprised a purely civil obligation which was itself novated. Fiscal Lota denied the motion to dismiss (Petition, p. 8). But, after the presentation of David's principal witness, petitioners filed the instant petition because: (a) the production of the Promisory Notes, Banker's Acceptance, Certificates of Time Deposits and Savings Account allegedly showed that the transactions between David and NSLA were simple loans, i.e., civil obligations on the part of NSLA which were novated when Guingona, Jr. and Martin assumed them; and (b) David's principal witness allegedly testified that the duplicate originals of the aforesaid instruments of indebtedness were all on file with NSLA, contrary to David's claim that some of his investments were not record (Petition, pp. 8-9). Petitioners alleged that they did not exhaust available administrative remedies because to do so would be futile (Petition, p. 9) [pp. 153-157, rec.]. As correctly pointed out by the Solicitor General, the sole issue for resolution is whether public respondents acted without jurisdiction when they investigated the charges (estafa and violation of CB Circular No. 364 and related regulations regarding foreign exchange transactions) subject matter of I.S. No. 81-31938. There is merit in the contention of the petitioners that their liability is civil in nature and therefore, public respondents have no jurisdiction over the charge of estafa. A casual perusal of the December 23, 1981 affidavit. complaint filed in the Office of the City Fiscal of Manila by private respondent David against petitioners Teopisto Guingona, Jr., Antonio I. Martin and Teresita G. Santos, together with one Robert Marshall and the other directors of the Nation Savings and Loan Association, will show that from March 20, 1979 to March, 1981, private respondent David, together with his sister, Denise Kuhne, invested with the Nation Savings and Loan Association the sum of P1,145,546.20 on time deposits covered by Bankers Acceptances and Certificates of Time Deposits and the sum of P13,531.94 on savings account deposits covered by passbook nos. 6-632 and 29-742, or a

total of P1,159,078.14 (pp. 15-16, roc.). It appears further that private respondent David, together with his sister, made investments in the aforesaid bank in the amount of US$75,000.00 (p. 17, rec.). Moreover, the records reveal that when the aforesaid bank was placed under receivership on March 21, 1981, petitioners Guingona and Martin, upon the request of private respondent David, assumed the obligation of the bank to private respondent David by executing on June 17, 1981 a joint promissory note in favor of private respondent acknowledging an indebtedness of Pl,336,614.02 and US$75,000.00 (p. 80, rec.). This promissory note was based on the statement of account as of June 30, 1981 prepared by the private respondent (p. 81, rec.). The amount of indebtedness assumed appears to be bigger than the original claim because of the added interest and the inclusion of other deposits of private respondent's sister in the amount of P116,613.20. Thereafter, or on July 17, 1981, petitioners Guingona and Martin agreed to divide the said indebtedness, and petitioner Guingona executed another promissory note antedated to June 17, 1981 whereby he personally acknowledged an indebtedness of P668,307.01 (1/2 of P1,336,614.02) and US$37,500.00 (1/2 of US$75,000.00) in favor of private respondent (p. 25, rec.). The aforesaid promissory notes were executed as a result of deposits made by Clement David and Denise Kuhne with the Nation Savings and Loan Association. Furthermore, the various pleadings and documents filed by private respondent David, before this Court indisputably show that he has indeed invested his money on time and savings deposits with the Nation Savings and Loan Association. It must be pointed out that when private respondent David invested his money on nine. and savings deposits with the aforesaid bank, the contract that was perfected was a contract of simple loan or mutuum and not a contract of deposit. Thus, Article 1980 of the New Civil Code provides that:t.hqw Article 1980. Fixed, savings, and current deposits of-money in banks and similar institutions shall be governed by the provisions concerning simple loan. In the case of Central Bank of the Philippines vs. Morfe (63 SCRA 114,119 [1975], We said:t.hqw It should be noted that fixed, savings, and current deposits of money in banks and similar institutions are hat true deposits. are considered simple loans and, as such, are not preferred credits (Art. 1980 Civil Code; In re Liquidation of Mercantile Batik of China Tan Tiong Tick vs. American Apothecaries Co., 66 Phil 414; Pacific Coast Biscuit Co. vs. Chinese Grocers Association 65 Phil. 375; Fletcher American National Bank vs. Ang Chong UM 66 PWL 385; Pacific Commercial Co. vs. American Apothecaries Co., 65 PhiL 429; Gopoco Grocery vs. Pacific Coast Biscuit CO.,65 Phil. 443)." This Court also declared in the recent case of Serrano vs. Central Bank of the Philippines (96 SCRA 102 [1980]) that:t.hqw Bank deposits are in the nature of irregular deposits. They are really 'loans because they earn interest. All kinds of bank deposits, whether fixed, savings, or current are to be treated as loans and are to be covered by the law on loans (Art. 1980 Civil Code Gullas vs. Phil. National Bank, 62 Phil. 519). Current and saving deposits, are loans to a bank because it can use the same. The petitioner here in making time deposits that earn interests will respondent Overseas Bank of Manila was in reality a creditor of the respondent Bank and not a depositor. The respondent Bank was in turn a debtor of petitioner.Failure of the respondent Bank to honor the time deposit is failure to pay its obligation as a debtor and not a breach of trust arising from a depositary's failure to return the subject matter of the deposit(Emphasis supplied).

Hence, the relationship between the private respondent and the Nation Savings and Loan Association is that of creditor and debtor; consequently, the ownership of the amount deposited was transmitted to the Bank upon the perfection of the contract and it can make use of the amount deposited for its banking operations, such as to pay interests on deposits and to pay withdrawals. While the Bank has the obligation to return the amount deposited, it has, however, no obligation to return or deliver the same money that was deposited. And, the failure of the Bank to return the amount deposited will not constitute estafa through misappropriation punishable under Article 315, par. l(b) of the Revised Penal Code, but it will only give rise to civil liability over which the public respondents have no- jurisdiction. WE have already laid down the rule that:t.hqw In order that a person can be convicted under the above-quoted provision, it must be proven that he has the obligation to deliver or return the some money, goods or personal property that he receivedPetitioners had no such obligation to return the same money, i.e., the bills or coins, which they received from private respondents. This is so because as clearly as stated in criminal complaints, the related civil complaints and the supporting sworn statements, the sums of money that petitioners received were loans. The nature of simple loan is defined in Articles 1933 and 1953 of the Civil Code.t.hqw "Art. 1933. By the contract of loan, one of the parties delivers to another, either something not consumable so that the latter may use the same for a certain time- and return it, in which case the contract is called a commodatum; or money or other consumable thing, upon the condition that the same amount of the same kind and quality shall he paid in which case the contract is simply called a loan or mutuum. "Commodatum is essentially gratuitous. "Simple loan may be gratuitous or with a stipulation to pay interest. "In commodatum the bailor retains the ownership of the thing loaned while in simple loan, ownership passes to the borrower. "Art. 1953. A person who receives a loan of money or any other fungible thing acquires the ownership thereof, and is bound to pay to the creditor an equal amount of the same kind and quality." It can be readily noted from the above-quoted provisions that in simple loan (mutuum), as contrasted to commodatum the borrower acquires ownership of the money, goods or personal property borrowed Being the owner, the borrower can dispose of the thing borrowed (Article 248, Civil Code) and his act will not be considered misappropriation thereof' (Yam vs. Malik, 94 SCRA 30, 34 [1979]; Emphasis supplied). But even granting that the failure of the bank to pay the time and savings deposits of private respondent David would constitute a violation of paragraph 1(b) of Article 315 of the Revised Penal Code, nevertheless any incipient criminal liability was deemed avoided, because when the aforesaid bank was placed under receivership by the Central Bank, petitioners Guingona and Martin assumed the obligation of the bank to private respondent David, thereby resulting in the novation of the original contractual obligation arising from deposit into a contract of loan and converting the original trust relation between the bank and private respondent David into an ordinary debtor-creditor relation between the petitioners and private respondent. Consequently, the failure of the bank or petitioners Guingona and Martin to pay the

deposits of private respondent would not constitute a breach of trust but would merely be a failure to pay the obligation as a debtor. Moreover, while it is true that novation does not extinguish criminal liability, it may however, prevent the rise of criminal liability as long as it occurs prior to the filing of the criminal information in court. Thus, in Gonzales vs. Serrano ( 25 SCRA 64, 69 [1968]) We held that:t.hqw As pointed out in People vs. Nery, novation prior to the filing of the criminal information as in the case at bar may convert the relation between the parties into an ordinary creditor-debtor relation, and place the complainant in estoppel to insist on the original transaction or "cast doubt on the true nature" thereof. Again, in the latest case of Ong vs. Court of Appeals (L-58476, 124 SCRA 578, 580-581 [1983] ), this Court reiterated the ruling in People vs. Nery ( 10 SCRA 244 [1964] ), declaring that:t.hqw The novation theory may perhaps apply prior to the filling of the criminal information in court by the state prosecutors because up to that time the original trust relation may be converted by the parties into an ordinary creditor-debtor situation, thereby placing the complainant in estoppel to insist on the original trust. But after the justice authorities have taken cognizance of the crime and instituted action in court, the offended party may no longer divest the prosecution of its power to exact the criminal liability, as distinguished from the civil. The crime being an offense against the state, only the latter can renounce it (People vs. Gervacio, 54 Off. Gaz. 2898; People vs. Velasco, 42 Phil. 76; U.S. vs. Montanes, 8 Phil. 620). It may be observed in this regard that novation is not one of the means recognized by the Penal Code whereby criminal liability can be extinguished; hence, the role of novation may only be to either prevent the rise of criminal habihty or to cast doubt on the true nature of the original basic transaction, whether or not it was such that its breach would not give rise to penal responsibility, as when money loaned is made to appear as a deposit, or other similar disguise is resorted to (cf. Abeto vs. People, 90 Phil. 581; U.S. vs. Villareal, 27 Phil. 481). In the case at bar, there is no dispute that petitioners Guingona and Martin executed a promissory note on June 17, 1981 assuming the obligation of the bank to private respondent David; while the criminal complaint for estafa was filed on December 23, 1981 with the Office of the City Fiscal. Hence, it is clear that novation occurred long before the filing of the criminal complaint with the Office of the City Fiscal. Consequently, as aforestated, any incipient criminal liability would be avoided but there will still be a civil liability on the part of petitioners Guingona and Martin to pay the assumed obligation. Petitioners herein were likewise charged with violation of Section 3 of Central Bank Circular No. 364 and other related regulations regarding foreign exchange transactions by accepting foreign currency deposit in the amount of US$75,000.00 without authority from the Central Bank. They contend however, that the US dollars intended by respondent David for deposit were all converted into Philippine currency before acceptance and deposit into Nation Savings and Loan Association. Petitioners' contention is worthy of behelf for the following reasons: 1. It appears from the records that when respondent David was about to make a deposit of bank draft issued in his name in the amount of US$50,000.00 with the Nation Savings and Loan Association, the same had to be cleared first and converted into Philippine currency. Accordingly, the bank draft was endorsed by respondent David to petitioner Guingona, who in turn deposited it to his dollar account with the Security Bank and Trust Company. Petitioner Guingona merely accommodated the request of the

Nation Savings and loan Association in order to clear the bank draft through his dollar account because the bank did not have a dollar account. Immediately after the bank draft was cleared, petitioner Guingona authorized Nation Savings and Loan Association to withdraw the same in order to be utilized by the bank for its operations. 2. It is safe to assume that the U.S. dollars were converted first into Philippine pesos before they were accepted and deposited in Nation Savings and Loan Association, because the bank is presumed to have followed the ordinary course of the business which is to accept deposits in Philippine currency only, and that the transaction was regular and fair, in the absence of a clear and convincing evidence to the contrary (see paragraphs p and q, Sec. 5, Rule 131, Rules of Court). 3. Respondent David has not denied the aforesaid contention of herein petitioners despite the fact that it was raised. in petitioners' reply filed on May 7, 1982 to private respondent's comment and in the July 27, 1982 reply to public respondents' comment and reiterated in petitioners' memorandum filed on October 30, 1982, thereby adding more support to the conclusion that the US$75,000.00 were really converted into Philippine currency before they were accepted and deposited into Nation Savings and Loan Association. Considering that this might adversely affect his case, respondent David should have promptly denied petitioners' allegation. In conclusion, considering that the liability of the petitioners is purely civil in nature and that there is no clear showing that they engaged in foreign exchange transactions, We hold that the public respondents acted without jurisdiction when they investigated the charges against the petitioners. Consequently, public respondents should be restrained from further proceeding with the criminal case for to allow the case to continue, even if the petitioners could have appealed to the Ministry of Justice, would work great injustice to petitioners and would render meaningless the proper administration of justice. While as a rule, the prosecution in a criminal offense cannot be the subject of prohibition and injunction, this court has recognized the resort to the extraordinary writs of prohibition and injunction in extreme cases, thus:t.hqw On the issue of whether a writ of injunction can restrain the proceedings in Criminal Case No. 3140, the general rule is that "ordinarily, criminal prosecution may not be blocked by court prohibition or injunction." Exceptions, however, are allowed in the following instances:t.hqw "1. for the orderly administration of justice; "2. to prevent the use of the strong arm of the law in an oppressive and vindictive manner; "3. to avoid multiplicity of actions; "4. to afford adequate protection to constitutional rights; "5. in proper cases, because the statute relied upon is unconstitutional or was held invalid" ( Primicias vs. Municipality of Urdaneta, Pangasinan, 93 SCRA 462, 469-470 [1979]; citing Ramos vs. Torres, 25 SCRA 557 [1968]; and Hernandez vs. Albano, 19 SCRA 95, 96 [1967]). Likewise, in Lopez vs. The City Judge, et al. ( 18 SCRA 616, 621-622 [1966]), We held that:t.hqw The writs of certiorari and prohibition, as extraordinary legal remedies, are in the ultimate analysis, intended to annul void proceedings; to prevent the unlawful and oppressive

exercise of legal authority and to provide for a fair and orderly administration of justice. Thus, in Yu Kong Eng vs. Trinidad, 47 Phil. 385, We took cognizance of a petition for certiorari and prohibition although the accused in the case could have appealed in due time from the order complained of, our action in the premises being based on the public welfare policy the advancement of public policy. In Dimayuga vs. Fajardo, 43 Phil. 304, We also admitted a petition to restrain the prosecution of certain chiropractors although, if convicted, they could have appealed. We gave due course to their petition for the orderly administration of justice and to avoid possible oppression by the strong arm of the law. And in Arevalo vs. Nepomuceno, 63 Phil. 627, the petition for certiorari challenging the trial court's action admitting an amended information was sustained despite the availability of appeal at the proper time. WHEREFORE, THE PETITION IS HEREBY GRANTED; THE TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER PREVIOUSLY ISSUED IS MADE PERMANENT. COSTS AGAINST THE PRIVATE RESPONDENT. SO ORDERED.1wph1.t Concepcion, Jr., Guerrero, De Castro and Escolin, JJ., concur. Abad Santo rres, Johnson and Trent, JJ., concur. G.R. No. L-33582 March 30, 1982 THE OVERSEAS BANK vs. VICENTE CORDERO and COURT OF APPEALS, respondents. OF MANILA, petitioner,

ESCOLIN, J.: Again, We are confronted with another case involving the Overseas Bank of Manila, filed by one of its depositors. This is a petition for review on certiorari of the decision of the Court of Appeals which affirmed the judgment of the Court of First Instance of Manila, holding petitioner bank liable to respondent Vicente Cordero in the amount of P80,000.00 representing the latter's time deposit with petitioner, plus interest thereon at 6% per annum until fully paid, and costs. On July 20, 1967, private respondent opened a one-year time deposit with petitioner bank in the amount of P80,000.00 to mature on July 20, 1968 with interest at the rate of 6% per annum. However, due to its distressed financial condition, petitioner was unable to pay Cordero his said time deposit together with the interest. To enforce payment, Cordero instituted an action in the Court of First Instance of Manila. Petitioner, in its answer, raised as special defense the finding by the Monetary Board of its state of insolvency. It cited the Resolution of August 1, 1968 of the Monetary Board which authorized petitioner's board of directors to suspend all its operations, and the Resolution of August 13, 1968 of the same Board, ordering the Superintendent of Banks to take over the assets of petitioner for purposes of liquidation. Petitioner contended that although the Resolution of August 13, 1968 was then pending review before the 1 Supreme Court, it effectively barred or abated the action of respondent for even if judgment be

ultimately rendered in favor of Cordero, satisfaction thereof would not be possible in view of the restriction imposed by the Monetary Board, prohibiting petitioner from issuing manager's and cashier's checks and the provisions of Section 85 of Rep. Act 337, otherwise known as the General Banking Act, forbidding its directors and officers from making any payment out of its funds after the bank had become insolvent. It was further claimed that a judgment in favor of respondent would create a preference in favor of a particular creditor to the prejudice of other creditors and/or depositors of petitioner bank. After pre-trial, petitioner filed on November 29, 1968, a motion to dismiss, reiterating the same defenses raised in its answer. Finding the same unmeritorious, the lower court denied the motion and proceeded with the trial on the merits. In due time, the lower court rendered the aforesaid decision. Dissatisfied, petitioner appealed to the Court of Appeals, which affirmed the decision of the lower court. Hence, this petition for review on certiorari. The issues raised in this petition are quite novel. Petitioner stands firm on its contentions that the suit filed by respondent Cordero for recovery of his time deposit is barred or abated by the state of insolvency of petitioner as found by the Monetary Board of the Central Bank of the Philippines; and that the judgment rendered in favor of respondent would in effect create a preference in his favor to the prejudice of other creditors of the bank. Certain supervening events, however, have rendered these issues moot and academic. The first of these supervening events is the letter of Julian Cordero, brother and attorney-in-fact of respondent Vicente Cordero, addressed to the Commercial Bank of Manila (Combank), successor of petitioner Overseas Bank of Manila. In this letter dated February 13, 1981, copy of which was furnished this Court, it appears that respondent Cordero had received from the Philippine Deposit Insurance Company the amount of P10,000.00. The second is a Manifestation by the same Julian Cordero dated July 3, 1981, acknowledging receipt of the sum of P73,840.00. Said Manifestation is in the nature of a quitclaim, pertinent portions of which We quote: I, the undersigned acting for and in behalf of my brother Vicente R. Cordero who resides in Canada and by virtue of a Special Power of Attorney issued by Vicente Romero, our Consul General in Vancouver, Canada, xerox copy attached, do hereby manifest to this honorable court that we have decided to waive all and any damages that may be awarded to the above-mentioned case and we hereby also agree to accept the amount of Seventy Three Thousand Eight Hundred Forty Pesos (P73,840.00) representing the principal and interest as computed by the Commercial Bank of Manila. We also agree to hold free and harmless the Commercial Bank of Manila against any claim by any third party or any suit that may arise against this agreement of payment. ... We also confirm receipt of Seventy Three Thousand Eight Hundred Forty Pesos (P73,840.00) with our full satisfaction. ... When asked to comment on this Manifestation, counsel for Combank filed on August 12, 1981 a Comment confirming and ratifying the same, particularly the portions which state: We also agree to hold free and harmless the Commercial Bank any third party or any suit that may arise against this agreement of payment, and We also confirm receipt of Seventy Three Thousand Eight Hundred Forty Pesos (P73,840.00) with our full satisfaction.