Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

79 79 1 PB

Загружено:

nurul0000 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

48 просмотров0 страниц79-79-1-PB

Оригинальное название

79-79-1-PB

Авторское право

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документ79-79-1-PB

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

48 просмотров0 страниц79 79 1 PB

Загружено:

nurul00079-79-1-PB

Авторское право:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 0

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

The Software Industry in Bangladesh and its Links to The Netherlands

Paul Tjia

GPI Consultancy

info@gpic.nl

Abstract

Organizations such as KLM, Philips and Baan in The Netherlands have been collaborating

with IT-suppliers in developing countries. Dutch software projects are now being executed in

many nations, and especially in Asia. India is the most popular country, but some Dutch

companies have chosen to outsource work to lesser-known IT-destinations, such as

Bangladesh. This country has more than 200 software houses and data-entry centres and

numerous computer shops. At present, there are around 20 - 30 Bangladeshi software

developers with foreign clients, some of which are 100% export orientated.

Several years ago, software was identified by the government of Bangladesh as

having important export potential. The total amount of software and IT-services exports is

currently estimated at a maximum of $ 30 million per year. Dijkoraad-hawar, a medium sized

IT company and Metatude, a start- up company are presented as Dutch case studies in this

paper. Each organization has set up a software development centre in Dhaka, and has been

satisfied with the results. One of the main advantages perceived by these users is the potent ial

for significant reduction in project costs. Also, qualified candidates can be found in

Bangladesh and cultural differences had no major impact.

1. INTRODUCTION

For more than 20 years, organizations in The Netherlands have been collaborating with IT-

suppliers in developing countries. There have been two major reasons for global software

outsourcing: the possibility to reduce costs and the availability of IT-skills abroad. Indian

software companies started offering their services to Dutch clients more than twenty years

ago. This country is now the most popular offshore destination and more than 200 Dutch

firms have outsourced IT-work to India. In recent years, vendors from many other countries

have been targeting The Netherlands as well.

Dutch software projects are underway in many developing nations, especially in Asia.

Compared with India however, these projects are much more limited in size and in number.

The IT-sectors of most of these countries are not well-recognised in Holland. For example,

only a few Dutch companies have chosen to outsource work to Bangladesh. The objective of

this article is to give a brief overview of the Bangladeshi IT-sector and its software exports,

and to identify the nature and extent of Dutch IT collaboration with Bangladesh.

2. THE BANGLADESHI IT-SECTOR

With a population of 130 million people, Bangladesh is one of the largest developing

countries in the world. According to BASIS (the Bangladesh Association of Software &

Information Services), some of the advantages of the Bangladeshi IT-sector are low labour

costs, high programmer productivity and a widespread knowledge of English. At present, 42

public and private universities and some institutes and colleges are offering degree courses in

the area of Information Technology. It is estimated that every year, around 3000 IT graduates

are coming out of these institutions. In addition, there are large numbers of IT training

centres, some of which are a foreign franchise. The rough enrolment in these centres is

around 12 thousand per year (BASIS, 2002). In general, basic technical knowledge in

Bangladesh is considered to be adequate. Students from BUET (Bangladesh University of

Engineering and Technology), Dhaka University and some private universities have excelled

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

2

in national and international computer programming competitions. Specific project and

business management skills however need to be upgraded (IBTCI, 2002). Most recruits are

from a technical or engineering background and as they progress in their careers additional

management skills will be required.

In Bangladesh, there are more than 200 software houses (although selling hardware is

often an important part of their services) and data-entry centres and numerous computer

shops. Most of these IT-companies are small or medium- sized; a company of 50 100 people

can be considered large. There are no extremely large enterprises, as is often the case in

neighbouring India. Although exact numbers are not available, the number of foreign IT-

companies is limited.

BASIS, the Bangladesh Association of Software & Information Services, is the

national association of software and IT firms, and was founded in 1998. It has a rapidly

growing membership, which at the beginning of 2003 stands at 82. BASIS organises

seminars, workshops, a national software programming contest and trade fairs, such as the

SoftExpo Bangladesh 2002. It also participates in foreign IT exhibitions in order to promote

the Bangladeshi IT sector (BASIS, 2002). Another organization is BCS (the Bangladesh

Computer Samity), which is a national association of all types of IT firms, including

hardware and software retailers, wholesalers, assemblers and developers. It has been

established in 1987 and has around 180 members. Some companies belong to both

associations. The BCC (Bangladesh Computer Council) is an autonomous body under the

Ministry of Science and Information & Communication Technology and provides support for

IT related activities as well. Recently, the Internet Service Providers Association of

Bangladesh was formed.

Around a dozen BASIS members are certified to the ISO 9001 quality assurance

standard. Measured against the Software Engineering Institutes Process Maturity Levels

(there are five levels) almost all Bangladeshi software development companies fall in the

lowest level (the Initial Level). To participate in the global software development industry,

the desired minimum level is Capability Maturity Measurement Integration (Level 3). Some

firms are now working towards obtaining a CMMI-Level 3 certification. Dutch companies

have observed that the quality of documentation and testing is sometimes inappropriate and

quality assurance is weak. This means that the software needs to be sent back to Bangladesh

for debugging and re-programming. The Dutch CBI (Centre for the promotion of imports

from developing countries), which is an agency of the Ministry of Development Cooperation,

started in 2002 to organise workshops on software project management for IT-professionals

in the capital Dhaka. This course is offered as part of an integral export promotion program

of CBI, which will also include export marketing assistance for a selected group of

companies.

When software was identified by the government of Bangladesh as an industry with

an important export potential, the Ministry of Commerce established a task force in 1997 to

identify methods by which this sector could be developed. A report, which was submitted by

a committee headed by Mr. Choudhury in September 1997, identified Bangladeshs

competitive advantages as

low labour costs

high programmer productivity

widespread knowledge of English

the availability of a wide range of hardware platforms

existence of an experienced software sector.

The report also ident ified four types of constraints (fiscal, human resources,

infrastructure and marketing). The main constraints were recognised as poor

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

3

telecommunications infrastructure, the insufficient number and capacity of ISPs and the lack

of contacts with international markets.

Of the task forces forty- five recommendations to the government and to the private

sector, twenty- five have been acted upon and nine more are being implemented (Choudhury,

2000). Computer hardware and software imports have been exempt from duties and taxes. A

10-year tax holiday for software and IT service companies has been established. 100%

foreign-owned companies are allowed and a 100% remittance of profit and capital gains for

foreign investors is possible. An IPR (Intellectual Property Rights) law was enacted in 2000

and an Electronic Transactions & Cyber Crimes Law is being drafted. Software and data

processing exporters are also eligible to benefit from the EPBs (Export Promotion Bureau)

market promotion fund.

Recently, with support from the World Bank, the BDXDP (Bangladesh Export

Diversification Project) issued on behalf of the Ministry of Commerce a report on supporting

the IT exports growth (IBTCI, 2002). The BDXDP recommended that a shared sales office

should be set up in the United States (Silicon Valley) to improve the penetration of foreign

markets. Its goal must be to promote and speed up direct contacts between exporters and

potential clients in the world's leading IT-market. This office is planned to be opened at the

end of 2002.

Personal contacts are extremely important in establishing business connections, as, for

example where Indian expatriates working in high- level technical and managerial positions in

the U.S. and U.K. have been very instrumental in the growth of Indian software exports

(Arora, 2001). The BDXDP report also mentioned that the Non-Resident Bangladeshi

community abroad can be a significant asset to Bangladeshi companies entering foreign

markets, e.g. through organizations such as TechBangla, SBIT (Silicon Bangla IT) or the

AABEA (American Association of Bangladesh Engineers and Architects). The focus of

promotional activities should be to create a number of successful exporting companies, rather

than working to create a strong Bangladesh country brand.

The report identified that although the number of Internet Service Providers is

growing rapidly, Bangladesh still has one of the lowest tele-densities in Asia (around 1 per

100 people although it has doubled over the last few years with cell phones significantly

contributing to it). Data transfer is poor and very expensive compared with competing

countries. For this reason, a temporary IT Village will be established with all the necessary

telecom facilities to provide temporary front office space to software exporters. An IT

incubator in the heart of Dhaka (at the 5 star Sonargaon Pan Pacific Hotel) has been

operational since November 2002, and tenants are welcomed. Recommendations were also

made in the fields of promoting direct investment (e.g. offering a 20 year tax holiday for

approved projects) and education (e.g. establishing advanced courses on specialist IT industry

management and marketing methods), (IBTCI, 2002).

3. SOFTWARE EXPORTS

International organizations such as the World Bank mentioned the trade opportunities for

developing countries in the field of IT already several years ago (Schware, 1992). A growing

export IT-sector is important for Bangladesh, since it generates foreign exchange and

provides for highly skilled jobs. To achieve this, the education system must produce better-

equipped students and the IT infrastructure should be improved. If such an IT- industry does

not develop, the problem of the brain drain will continue to exist. Around 80% of graduates

and teachers have indicated that they would migrate to other countries if they could

(UNCTAD, 2001). So far, Bangladesh has lost the majority of its scientists, technologists and

engineers to the western world.

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

4

Exporting IT services from developing nations such as Bangladesh is a complicated

process (Tjia, 1999; IBTCI, 2002). Exporting software products is even more difficult. It will

always take a lot of time and effective marketing is essential for any successful market

penetration. It is still difficult for potential Dutch or European clients to find suitable

information about the Bangladeshi IT-sector. Users that collaborate with Bangladesh are

scarce and there are hardly any articles being printed on this subject in magazines. One way

to change this and to conduct marketing and sales activities is to open a marketing office

abroad. More than 300 Indian software firms established offices in Europe, especially in the

U.K. Only with a local presence can marketing be done at an optimal level, but not a single

IT-company from Bangladesh has an office in Europe yet. An alternative is to use l ocal

marketing partners or business agents.

Most successful companies in developing nations have started on a small scale and

built their businesses up gradually. This should be the goal for Bangladesh as well.

Nevertheless, export promotion is both expensive and time-consuming. Firms must be

prepared to invest in marketing, especially in fields such as commercial representation, pre-

sales consultancy, match- making, networking, advertising and travel. Because of these

factors, the market entry costs are high. These high costs are one of the main disadvantages of

the export of IT-services (Heeks, 1992).

In 2003, an estimated 20 - 30 Bangladeshi software developers, some of which are

100% export orientated, are working for foreign clients. Most of these exporters are service

providers or sub-contractors working with overseas software developers; others develop and

market their products direct to end users in the foreign markets. Apart from software

development, also IT-services such as data-processing, GIS, 2D and 3D animation and

multimedia are offered to foreign clients. There are no exact data, but the total software and

IT-services exports are currently estimated at a maximum of $ 30 million per year.

The major export market is the United States, where most of the marketing activities

are taking place. Firms from Bangladesh are regularly attending the Comdex exhibition, both

as visitors and exhibitors. A convention, TechTransfer, organized by a committee

representing the private sector, the government and universities, was held in April 2000 in

Atlantic City, U.S. (TechTransfer, 2000). It brought together resident and non-resident

Bangladeshi IT professionals, to exchange views and knowledge and to discuss ways to

promote the development of IT in Bangladesh. As a follow- up, TechTransfer 2 took place in

December 2000 in Dhaka.

Apart from the United States, Bangladeshi companies also work for clients in various

European countries, such as France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Denmark, U.K., Switzerland

and The Netherlands. The number of projects and the size of contracts however are limited,

even though the working history is relatively long. Already in 1988, a software company was

set up in Dhaka that exported software and IT services to Volvo Motor Company in Sweden.

In 1989 another software company was started that had the large U.K.-based ICI

Pharmaceuticals among its export clients. Unfortunately the tempo of growth of this industry

could not be maintained due to many factors - some political, some infra-structural and some

due to lack of a facilitating policy framework (IBTCI, 2002).

Compared with India, the IT-sector of Bangladesh is hardly visible in Europe. The

public presence of vendors from Bangladesh was mainly limited to participations at the

CeBIT in Hannover, Germany, which is the largest IT-exhibition in the world. In recent

years, stalls at this fair are being sponsored by the DCCI (Dhaka Chamber of Commerce) and

the EPB (Export Promotion Bureau). Also the Dutch CBI (Centre for the promotion of

imports from developing countries) sponsored the participation at CeBIT of IT-companies

from Bangladesh for several years. This was part of a marketing support project which started

in 1995 and ended in 2000, when five companies (CITech Communications, Computer

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

5

Services, DECODE, Leads Corporation and Texas Electronics) presented themselves at the

exhibition.

Companies from Bangladesh can sometimes be seen at other occasions. A recent IIR

Offshore Outsourcing conference in London (May 2002) was sponsored by BASIS and some

of the largest Bangladeshi firms including TechnoVista, Flora Systems, TCL, CreateMatix

and CSL Software Resources were participating at the seminar. A software marketing

delegation arranged by the Export Promotion Bureau visited several European countries,

including The Netherlands, during October 2002.

4. THE CONNECTION WITH THE NETHERLANDS

Germany is the largest national market for Information Technology in Europe, followed by

the United Kingdom, France and Italy. The Netherlands ranks number five in size (EITO,

2000). For more than 20 years, companies in The Netherlands have been using the services of

IT-suppliers in developing countries. The Dutch, who have been international traders for

centuries and who, compared with other European countries, have an international outlook

are often willing to cooperate with foreign companies. An important advantage of offshore

outsourcing is the possibility to reduce costs. Until the current economic recession, there has

been a serious shortage of specialised IT-skills in The Netherlands for many years (FENIT,

2001). In developing countries, low cost and experienced software engineers are available in

large numbers.

Dutch enterprises limit their orders primarily to India. Although the Dutch IT- market

is relatively small, more than 200 Dutch companies have had their software developed in

India. On a more incidental basis, software orders have also gone to many other developing

countries and especially to Asia (Tjia, 1999). Dutch software destinations in Asia are Turkey,

Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia (a

former Dutch colony), China and North Korea (also attractive for its advanced animation

sector).

Four types of international IT-collaboration can be distinguished:

The client works temporarily together with a foreign software house for the duration of

one or more projects. This is relatively uncomplicated and is the most popular way. Dutch

based companies such as ABN Amro Bank, Atos Origin, the KLM and ING Group are

working like this. In these cases, most of the work is being done offshore; on-site

assignments are less popular.

Joint ventures with foreign IT companies. This will intensify the relationship between the

two organizations. An example of this is OTS (Orange Telecom Software), a joint venture

that was started in 1991 between the Dutch KPN Telecom and TCIL of India. Joint

ventures in the field of software development are still very rare; OTS has been closed

recently.

Dutch companies establish subsidiaries abroad. This is useful if large amounts of software

need to be created. For this purpose, enterprises such as Philips, Vanenburg and

Invensys/Baan have set up subsidiary companies in India. The ABN Amro Bank operated

a software facility in Lahore (Pakistan). Another IT- firm recently set up an office in

Kathmandu (Nepal).

Foreign IT specialists can be employed directly and work on site. This method is not

often used but, because of the scarcity of certain qualified personnel, some Indians are

living and working in The Netherlands.

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

6

In recent years, some Dutch companies decided to outsource software projects to

Bangladesh. The author estimates that not more than five Dutch organizations have had IT-

experiences with this country. The author discussed this with three of these companies.

The level of IT-education in Bangladesh is in general sufficient for the Dutch firms. Although

these clients were relatively small and internationally unknown, they had no problems in

finding qualified candidates in Bangladesh. The total costs per programmer are much lower

than in India and compared to The Netherlands, cost savings of more than 50% (including

overhead) could be achieved. There is a risk that staff leaves for a position abroad (especially

the U.S. is a popular destination). However, they will tend to stay if the project is challenging

(e.g. using new technology) or if a better working condition, additional training and other

incentives can be offered.

5. CASE STUDIES OF DUTCH-BANGLADESH OUTSOURCING

Dijkoraad-hawar is a medium sized Dutch IT company specialized in the integration of

graphical and alphanumerical information in technical environments (e.g. Computer Aided

Design, Geographical Information Systems, Facilities Management). It has five offices in

Holland. Providing IT-services is one of their activities and since 1998, they are working with

a partner in Bangladesh. In Dhaka, the capital of the country, a small team of 5 programmers

is producing software for the (Dutch) clients of Dijkoraad-hawar. One of their recent products

was a service management module to be used by the Dutch national airline KLM. The choice

for Bangladesh was by coincidence. One of the founders of the company, who later pursued

his career in development-aid related projects, had an assignment in Bangladesh. When he

came in contact with local software companies, he was surprised by their experiences and

skills. He succeeded in establishing an initial relationship between one of these firms and

Dijkoraad-hawar. The cooperation started when a staff member from Bangladesh spent

several months in The Netherlands for training and familiarisation. After this period, all

communication could take place through the Internet and by telephone. So far, no need was

felt for Dutch staff to travel to Dhaka. In 2002, Dijkoraad-hawar started a second activity in

Dhaka: data processing.

Another Dutch example is Amsterdam-based Metatude, which was set up in the

beginning of 2000. It produces and markets software products, that allow its clients to

develop on- line dialogues with stakeholders (e.g. surveys through the Internet). The founders

of the company had planned to do all the software development activities in Amsterdam and

rented a large office space for this purpose. In 2000 however, in the middle of the Internet-

hype, it was not possible to recruit the required number of staff. Nobody seemed to be willing

to work for an unknown start- up and the management was forced to consider offshore

alternatives. They hired the assistance of a consultant of GPI Consultancy, and initially, three

countries were looked at: Bulgaria (a Bulgarian IT-promotion project was active at that time),

India (well-known) and Bangladesh (where the consultant had contacts). In each country,

several software companies were contacted through e- mail. The feedback from Bulgaria was

poor and not very convincing. India had a large choice of qualified suppliers but seemed to be

expensive for a start-up with limited funding. Rather surprisingly for Metatude, the answers

received from Bangladesh were detailed and responsive.

To gain more information, the next step for Metatude was to travel to Dhaka. During

two weeks, meetings took place with ten local IT-service providers, some foreign companies

and the Dutch Embassy. It was found out that sufficient IT-staff were available and that the

costs to develop software were low compared to Holland. There did not seem to be a very

large turnover of staff as was the case in India, also because of the low number of foreign

companies in Bangladesh. It was also noticed that the international experience of firms in

Bangladesh was limited and that the infrastructure was not very sophisticated. At the end of

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

7

the visit, three local companies were invited to work out a RFP (Request For Proposal).

Finally, one partner, the owner of a small IT services company, was chosen. This person and

his team were to be employed by Metatude and at the end of 2000, a subsidiary organization

was set up in Dhaka. It was a disappointment that a senior architect could not be found

locally (not even in nearby Calcutta in India). This meant that the Dutch project leader had to

stay in Dhaka for a much longer period than originally planned. Dhaka was considered a safe

place with less crime than in Amsterdam, but the nois y city is not always particular attractive

for foreigners for a long stay.

Around sixteen people are now working for the project and the overall outlook is

positive. An important reason for the success was the involvement of an experienced local

partner. The cultural differences had no major impact and appeared to be less than with

Indians. The working environment was friendly and has an informal atmosphere. No

experiences with corruption were encountered. Nevertheless, a lot had to be learned since the

team in Dhaka had not developed packaged software for a foreign client earlier. There was

not much experience with managing complex projects either. The infrastructure was

sometimes disappointing (e.g. slow Internet access). This all had a negative impact on the

communication between the Dutch team and the staff in Dhaka, and especially in the

beginning. This meant that much more time and effort was required than originally expected,

which resulted in delays. The first version of the product has now been delivered and work

has started on the updates.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Bangladesh can be considered a potential destination for software outsourcing. The Dutch

companies that worked with a partner from Bangladesh were satisfied with the results. One of

the most interesting advantages is the potential to achieve a significant reduction in project

costs. There is not a very large turnover of staff and the cultural differences had no major

impact. These are advantages Bangladesh has over competing countries in the region, such as

India.

The IT sector of Bangladesh is not yet well known internationally and the software

exports are still limited. Many of the local IT companies do not yet have international

experience. To improve this situation, export promotion should be a major goal for

Bangladesh. Firms must be prepared to invest in marketing activities such as commercial

representation, networking and advertising. If that is the case, then more companies from

Bangladesh might be able to generate revenue from the Dutch market for global software

outsourcing.

7. REFERENCES

Arora, A. (2001). The Software Industry and Indias Economic Development. United

Nations University/WIDER, Helsinki.

BASIS (2002). Think offshore, think Bangladesh, Dhaka. Presentation at the IIR

Offshore Outsourcing conference, London 27 - 28 May.

Choudury, N., A.J. M. Akkas (2000). Selling Software, in: PC Quest, Dhaka,

September.

EITO (2000), European Information Technology Observatory, Frankfurt/Main.

FENIT (2001). Federation Dutch IT, ICT Market Monitor, Woerden.

Heeks, R. (1992). Shortcomings of the Software Export Model. In: Cyranek, G. and

Bhatnagar, S.C. (ed.), Technology Transfer for Development. New Delhi, Tata McGraw-Hill.

IBTCI (2002). A Market Study on Diversification of Bangladesh Software Exports.

Compiled by International Business and Technical Consultants Inc., on behalf of BDXDP

(Bangladesh Export Diversification Project), Dhaka.

EJISDC (2003) 13, 5, 1-8

The Electronic Journal on Information Systems in Developing Countries,

http://www.ejisdc.org

8

Schware, R. (1992). The World Software Industry and Software Engineering:

Opportunities and Constraints for NIEs. World Bank Technical Paper nr. 104, Washington,

The World Bank.

TechTransfer (2000). Atlantic City. Bangladesh, a bond through technology,

Bangladesh Organizing Committee, Dhaka.

Tjia, P. (1998). Offshore Software Development. CBI News Bulletin, Rotterdam, nr.

259.

Tjia, P. (1999). Computer software and IT services: a survey of the Netherlands and

other major markets in Europe. A handbook for exporters from developing countries. CBI

(Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries), Rotterdam.

UNCTAD (2001), E-commerce and Development Report 2001, United Nations, New

York/Geneva.

8. APPENDIX

The following webpages have been accessed on April 15, 2003:

Bangladesh Government: www.bangladeshgov.org

BASIS: www.basisb.org

Bangladesh Computer Council: www.bccbd.org

Bangladesh Computer Samity: www.bcs-bd.org

Export Promotion Bureau: www.epbbd.org

The Federation of Bangladesh Chambers

of Commerce and Industry: www.fbcci-bd.org

Cyber Bangladesh: www.cyberbangladesh.org

Portal on Bangladesh: www.bangla2000.com

Author Bio:

Paul Tjia has degrees in Cultural Anthropology and Information Technology. He has more

than 15 years experience in IT and is specialised in global IT outsourcing. He works as a

senior consultant at GPI Consultancy in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. This company, which

he founded in 1994, is one of the few independent Dutch consultancy firms in the field of

offshore IT outsour cing. Paul conducts research on this subject and has written several

articles in Dutch magazines. He is also a speaker at (international) seminars.

He promotes global outsourcing in Holland through seminars and study tours. He assists

Dutch clients with feasibility study and country and partner selection (e.g. in Central and

Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Asia). He conducts workshops in dealing effectively

with different cultures (e.g. 'how to deal with the Dutch culture' for Indian IT-staff and 'how

to deal with the Indian culture' for Dutch users).

Вам также может понравиться

- Driving Digital Innovation For A Sustainable Inclusive GrowthДокумент209 страницDriving Digital Innovation For A Sustainable Inclusive Growthnurul000100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Appointment of External Auditors in Financial Institutions - Apr302015dfim04eДокумент3 страницыAppointment of External Auditors in Financial Institutions - Apr302015dfim04enurul000Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Name Change - Feb032019dfiml01Документ1 страницаName Change - Feb032019dfiml01nurul000Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Stamp RequisitionДокумент20 страницStamp Requisitionnurul000Оценок пока нет

- Write Off - Apr082015fid03Документ1 страницаWrite Off - Apr082015fid03nurul000Оценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Avoidance of High Expenses For Luxurious Vehicles and Decoration - Nov182015dfim12eДокумент1 страницаAvoidance of High Expenses For Luxurious Vehicles and Decoration - Nov182015dfim12enurul000Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Cheque Clearing FeeДокумент1 страницаCheque Clearing Feenurul000Оценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Bankers' Book Evidence Act, 1891Документ4 страницыThe Bankers' Book Evidence Act, 1891nurul000Оценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Sep182018dfim03Документ4 страницыSep182018dfim03nurul000Оценок пока нет

- Application - Form of BkmeaДокумент3 страницыApplication - Form of Bkmeanurul000Оценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Table-A: CAF (For Asset-Side Products) : Description of Loan/Lease FacilityДокумент4 страницыTable-A: CAF (For Asset-Side Products) : Description of Loan/Lease Facilitynurul000Оценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Bank Asia ATM LocationsДокумент4 страницыBank Asia ATM Locationsnurul000Оценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Payment Settlements R 2009Документ8 страницPayment Settlements R 2009nurul000Оценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- ALM Maturity Profile 1Документ8 страницALM Maturity Profile 1nurul000Оценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Forfaiting: Dr. Prashanta K. BanerjeeДокумент4 страницыForfaiting: Dr. Prashanta K. Banerjeenurul000Оценок пока нет

- Know Your Marketability Know Your Marketability Know Your Marketability Know Your MarketabilityДокумент22 страницыKnow Your Marketability Know Your Marketability Know Your Marketability Know Your Marketabilitynurul000Оценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- An Overview of ITPFДокумент3 страницыAn Overview of ITPFnurul000Оценок пока нет

- Rate of Interest PhonixДокумент1 страницаRate of Interest Phonixnurul000Оценок пока нет

- Schedule of Charges Credit CardДокумент2 страницыSchedule of Charges Credit Cardnurul000Оценок пока нет

- United Commercial Bank LTD: For The Year Ended 31st December 2005Документ1 страницаUnited Commercial Bank LTD: For The Year Ended 31st December 2005nurul000Оценок пока нет

- Poisson Probability Distribution 97 2003Документ6 страницPoisson Probability Distribution 97 2003nurul000Оценок пока нет

- Segmenting Targeting & PositioningДокумент21 страницаSegmenting Targeting & Positioningnurul000Оценок пока нет

- Sample 7: Acceptance Letter (Full Block Format) : (Written Signature)Документ1 страницаSample 7: Acceptance Letter (Full Block Format) : (Written Signature)nurul000Оценок пока нет

- AMAEducation System Student Handbook - 2019 PDFДокумент300 страницAMAEducation System Student Handbook - 2019 PDFMichelle BonghanoyОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Faculty Should Have One's Own Room For Effective Teaching Without Hectic Work Load and Undetermined Hours - A Study in A Marxist PerspectiveДокумент6 страницFaculty Should Have One's Own Room For Effective Teaching Without Hectic Work Load and Undetermined Hours - A Study in A Marxist PerspectiveIJRASETPublicationsОценок пока нет

- Theme 3 Pervaiz Hudbouy 1Документ31 страницаTheme 3 Pervaiz Hudbouy 1Sultan AbbasОценок пока нет

- Universities For Girls in UAEДокумент11 страницUniversities For Girls in UAEGosia PiotrowskaОценок пока нет

- Ivy LeagueДокумент75 страницIvy LeagueSam CooperОценок пока нет

- MBA Handbook 19 20Документ247 страницMBA Handbook 19 20Bhupender YadavОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Malaysia PDFДокумент39 страницMalaysia PDFLeeahna JkОценок пока нет

- Judgement - Erb Vs MmustДокумент50 страницJudgement - Erb Vs Mmustnjerumwendi100% (1)

- JGU Anti-Ragging Ordinance & Rules Against Sexual Harassment PDFДокумент160 страницJGU Anti-Ragging Ordinance & Rules Against Sexual Harassment PDFYashmita BhallaОценок пока нет

- Case Study - St. Francis College of CommerceДокумент2 страницыCase Study - St. Francis College of CommerceHazelyn YuОценок пока нет

- Aturan Pendirian PTS ThailandДокумент28 страницAturan Pendirian PTS ThailandChristy JojobaОценок пока нет

- Yayasan Al BukharyДокумент11 страницYayasan Al Bukharyنور شهبره فانوتОценок пока нет

- Megha Sinha - Capstone Project 2021 - PHASE-2Документ69 страницMegha Sinha - Capstone Project 2021 - PHASE-2Megha SinhaОценок пока нет

- The Weakest LinkДокумент94 страницыThe Weakest Linkmariam_sabriОценок пока нет

- List of Central Luzon Colleges and UniversitiesДокумент30 страницList of Central Luzon Colleges and UniversitiesPaolo NgОценок пока нет

- Survey Report Without Survey Method (Group-2)Документ27 страницSurvey Report Without Survey Method (Group-2)Zawyar ur RehmanОценок пока нет

- Bus4090 Term PaperДокумент11 страницBus4090 Term PaperJosh GichohiОценок пока нет

- AmityДокумент101 страницаAmityPrashant TyagiОценок пока нет

- Assignment On Corporate GovernanceДокумент11 страницAssignment On Corporate Governanceiftekharul alamОценок пока нет

- Quality Assurance Practices in Higher Education in AfricaДокумент53 страницыQuality Assurance Practices in Higher Education in AfricaLuvonga CalebОценок пока нет

- Rti CMJ UniversityДокумент2 страницыRti CMJ UniversityAbhijit Kulshreshtha100% (2)

- Handbook For Quality Assurance and Accreditation in Saudi Arabia - 3Документ75 страницHandbook For Quality Assurance and Accreditation in Saudi Arabia - 3Majmaah_Univ_PublicОценок пока нет

- General Manual of Accreditation PDFДокумент57 страницGeneral Manual of Accreditation PDFkannambiОценок пока нет

- Compare and Contrast Between Private and Public Universities in DhakaДокумент2 страницыCompare and Contrast Between Private and Public Universities in DhakaMd. Mahade Hasan (153011061)Оценок пока нет

- Malaysian Private Higher Education: A Need To Study The Different Interpretations of QualityДокумент5 страницMalaysian Private Higher Education: A Need To Study The Different Interpretations of QualitySyazwan Samsol KaharОценок пока нет

- Education System of Peru and AustraliaДокумент2 страницыEducation System of Peru and AustraliaNaomi Ishii TairaОценок пока нет

- Compiled ABS EducationДокумент6 страницCompiled ABS EducationpbariarОценок пока нет

- Stakeholder Groups of Public and Private UniversitДокумент22 страницыStakeholder Groups of Public and Private UniversitPhương VõОценок пока нет

- Numl Front PageДокумент4 страницыNuml Front PageMATEEN AHMEDОценок пока нет

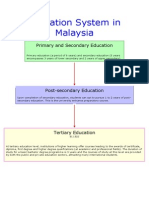

- Education System in MalaysiaДокумент7 страницEducation System in MalaysiaKevinОценок пока нет