Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Competition in The 'Corruption Market': The Challenge in Curbing Corruption

Загружено:

cornydeeИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Competition in The 'Corruption Market': The Challenge in Curbing Corruption

Загружено:

cornydeeАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

What are the challenges and associated solutions for companies working

together in Collective Action to fight corruption?

By Cornelius Dube, 20 April 2009

Abstract

This paper discusses corruption as referring to the offering, giving, receiving, or

soliciting, directly or indirectly of anything of value to influence improperly the actions

of another party. It focuses on corruption by agents at company level; implying those

corrupt activities financed by the companies and intended to benefit the company rather

than individuals. Participation by companies in these activities has resulted in the

prisoner’s dilemma strategy, where the dominant strategy is to participate in corruption,

as refraining to do so would enhance competitors’ chances of getting the associated

product or service. This has resulted in the creation of another market, the ‘corruption

market’, intertwined with the product or service market.

The paper discusses the challenges that the existence of the ‘corruption market’ poses

towards a collective action by the business in fighting corruption. These include the

difficulty in getting more details on its operations; getting competitors to avoid

participating when each has an incentive to cheat; challenges in initiating the collective

action process; financing of the collective action process and the factors outside the

business sector’s influence such as the pressure exerted by the public sector.

The paper recommends the use of existing bodies and associations in the business sector

in overcoming each of these challenges. This would see the establishment of a Committee

to oversee the whole process, which would also be part of a national reference group to

get buy-in from national stakeholders. Thus, while the efforts by the business sector in

collective action would significantly reduce corruption, an initiative involving all

stakeholders initiated by the business would achieve more. The starting point however

would be the business sector, as they are the most active participant in the corruption

market.

1. Introduction

Normally, when the word corruption is mentioned, what comes into the mind is a

government/public official being involved in underhand dealings with a private entity or

person. This is just one facet of corruption, normally referred to as private-to-public

corruption in that a private player would be paying some additional unofficial payments

to the public official for some business gain. The common definition of corruption as the

abuse of public office for private gain may also be taken to imply that private entities or

players by themselves, away from the public offices can not be corrupt. However, focus

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

on corruption has since moved to all players in the market and not only on public

officials.

On its website, Transparency International defines corruption as the misuse of entrusted

power for personal or private gain. It becomes apparent that any individual who finds

himself with some position of power can be corrupt, regardless of whether the individual

is from the public or private sector. Most importantly, the private sector players may be

involved in corruption on their own without public officials, normally referred to as

private-to-private corruption. Thus arguably the private sector players are the more active

players in the ‘corruption market’ than the public officials.

While understanding the merits of the arguments presented by some authors that there

could be some positive sides to corruption, such as in speeding up processes that could be

delayed by bureaucratic tendencies or its role as a price mechanism to correct

disequilibria in resource allocation (Clarke and Xu, 2001), the negative sides of

corruption are well documented and will far outweigh any purported positives.

Corruption steeply increases business costs, as it adds up to about 10% to the total cost of

doing business globally, up to 25% to the cost of procurement contracts in developing

countries, and its costs constitute more than 5% of global GDP (International Chamber of

Commerce, Transparency International, the United Nations Global Compact and the

World Economic Forum Partnering Against Corruption Initiative, 2008). Corruption

scares away foreign investors, thereby preventing job creation and limiting sustainable

development, and acts as a real barrier to development and business growth over time at

company, industry, national and global levels (World Bank Institute, 2008).

This paper focuses on the business’s role in corruption and how such actions have further

made it more challenging for companies to work together in collective action to fight

corruption. Its focus is on corruption aimed at benefiting the company rather than the

individual, the assumption being that it would be a company sanctioned venture, as the

costs to facilitate it would be financed by the company. The context therefore includes

both private-to-private corruption and private-to-public corruption, and not ‘petty

corruption’, which takes place at lower levels of the administration (Boehm, 2007).

Corruption in this context is therefore the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting,

directly or indirectly of anything of value to influence improperly the actions of another

party (IFI Anti-corruption Task Force, 2006).Thus corruption discussed here could be

with respect to bribery, extortion, or even state capture but the participants would be

doing so in their capacity as representatives of companies.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes how business has

managed to create a ‘corruption market’ and the associated challenges that this brings

towards a collective approach to fighting corruption. Section 3 proposes some

mechanisms through which companies, in consultation with other stakeholders, can use

to address such challenges. Concluding remarks then follow in section 4.

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

2. Business Challenges in fighting corruption

2.1 The ‘Corruption Market’

Companies generally engage in corruption as a way of beating their rivals to a service. In

other words, corruption is regarded as a way of surviving competition albeit unfairly. As

such it is business that is both the victim and the perpetrator; while one company is

successful in landing a bid or service through the use of corruption; others are counting

their losses due to this unfair competition. It is also apparent that companies are very

much aware of instances in which they have lost out because of corruption, either

because they have also participated before or because they have been informally

informed. PricewaterhouseCoopers International (2008) reported that in a survey almost

45% of respondents say they have not entered a specific market or pursued a particular

opportunity because of corruption risks. In other words, due to fear that they can not

fairly compete in the corruption prone market, the number of players is substantially

lower than its potential, giving higher probability of success for corruption to the

remaining companies. About 39% also said their company has lost a bid because of

corrupt officials, and 42% say their competitors pay bribes. If such a high percentage is

victims of corruption, it is difficult to imagine that there could only be one or two

companies that have so many victims. Rather it is apparent that there are many

companies that are involved, some preferring to compete all the way along. In such a

process, companies are now also competing for corruption in addition to the associated

service or product; hence the existence of a ‘corruption market’.

It is not difficult to understand how the competition for corruption comes about even

though the ‘corruption market’ can be difficult to delineate outside the associated

product/service market. A firm will not necessarily know the number of firms who will be

willing to participate in corruption, even though the number of firms in the market is

known. Thus a prisoner’s dilemma situation would come out, where a firm has to decide

whether to pay the corruption cost (say a bribe for example) or not. The firm will know

that if any of its competitors pay the bribe, then its chance will decrease, hence the

strategy to pay the bribe would enhance its chances. Thus it is not too off the mark to

assume that in markets that are more prone to collusion such as procurement and

constructions markets, a significant number would opt to pay bribes. This knowledge that

competitors will also pay bribes eventually creates a platform where firms will bid up the

bribe as well; hence the costs of corruption would be directly proportional to the number

of players in the corruption market. This makes the competition twofold; the product

competition and the ‘corruption’ competition.

It can be generally argued that it is difficult to separate corruption and collusion, given

that the same markets susceptible to cartels are also vulnerable to corruption. There is

much in common between cartels and corruption, as both strive to create an uneven

playing field for competitors in the market. It is during the process of bribe

competition where awareness of competitors and the nerve for cartel activities, such as

schemes for bid-rigging, price fixing or market allocation activities,

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

emerge. It would not be surprising for investigations that uncover illegal

payments to also uncover cartel activity involving multiple firms and their executives.

As the cost of corruption goes up with the number of participants in the ‘corruption

market’, there are high barriers to entry into the corruption game. This is also

compounded by the fact that there are also transaction costs of corruption, which are high

due to the need to avoid detection and the penalties once caught. This may lead to

situations where risk averse or honest firms exit the market, leaving fewer players in the

market. A combination of high entry barriers and few players in the market is a recipe for

cut-throat competition; hence there is basis to assume that the ‘corruption market’ would

be highly concentrated with those firms with financial muscles being able to ‘out-corrupt’

others and winning most of the corrupt business arrangements. This also leads to the

same scenario normally witnessed in the goods market, where fierce competition will

result in firms opting for collusive behaviour. Thus it is also not far fetched to expect to

find ‘corruption cartels’ in susceptible markets.

2.2 The challenges

Having discussed how the private sector actively participates in the corruption market, it

may not be difficult to understand the need for the players to work together in collective

action to fight corruption. Given that corruption has resulted in the creation of the

secondary market, which is deeply entangled with the genuine market and hidden;

ridding corruption becomes beyond the scope of individual corporations. Actions by one

company will not have significant impact in the corruption market unless complemented

by the others. This definitely calls for a collective approach to the situation, where both

actual and potential players in the two markets (good and corruption) have to work

together to be rid of the vice. The success of such an approach depends on the

development of a collaborative and sustained process of cooperation in fighting

corruption between all stakeholders.

This is prone to several challenges, none which is fortunately insoluble. Firstly, it is

difficult for firms to accept that they are participants in the corruption market, for they are

not immune to prosecution, even if they admit it as part of solution seeking. Thus a more

detailed disclosure on the operation of the market, which would form basis for collective

action solutions, is difficult to comprehend.

Secondly, getting firms who are used to working outside the competitive framework to

work together is always difficult, as each has an incentive to cheat fair competition

principles. Competing firms will always regard each other with suspicion if one of them

takes an active role in calling and trying to organise the framework for collective action.

Thirdly, it would be difficult for the firms to work together in the elimination of this

implicitly defined corruption market, and avoid the same for the explicitly defined

product market, give that the two markets are intertwined. Thus developing collective

strategies for the corruption market may easily result in collusive behaviour in the

product market, on which competition laws can descend heavily.

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

Fourth, it is also important to understand that the interests of the companies can rarely

converge; victims of corruption would want the practice to end while those that have

benefited most have incentives to see the trend continuing. Small companies with little

resources to finance corruption or to finance the compounded penalties once caught,

would be interested more in participating in the collective action while big firms with

deep pockets would reluctantly participate. The collective action plan therefore needs to

give incentives for all companies to take part.

Fifth, some resources are obviously required in mobilising stakeholders for such an

approach to evolve and get buy-in by all companies and stakeholders. Such resources

would need financing and the challenge is to ensure that while the resources are being

sought, no big dents are made to the firms’ pockets; otherwise they would prefer to be

free riders, knowing that the enjoyment of the ultimate benefit of a corruption free market

would be non-exclusive.

Finally, it would be difficult for business to have a strategy without taking into account

the potential reactions of the other party involved; that is the public sector. As long as the

public office abusers are totally left out of the process, they will continue to put spanners

on the strategies, to continue getting their shares. As Mitra (2003) argues, corruption in

the public office is difficult to stop as it is also a result of corruption; a cycle which is in

the interest of the players to preserve. Most of the agents participate in the corruption

market as a way of recouping the costs of corruption that they also paid in gaining their

position. This includes examples where agents borrow money to finance corruption, and

the repayment, with interest, will also have to be financed by corruption as the formal

earnings would not be enough. Thus collective action not endorsed by public agents will

be highly prone to sabotage.

A collective action plan for companies to work together should therefore be developed

with these challenges in mind.

3. Possible strategies for collective action

Lack of transparency and accountability in the public sector is normally a recipe for

corruption. So too is the existence of loopholes in the regulatory regime and enforcement

of various laws, including the anti-corruption law. It is the private sector which has first

hand information concerning the level of transparency and accountability in the public

sector, as it deals with the public sector regularly. It is also the private sector which is best

suited to judge the strength of the anti-corruption regulatory regime in the country, as

their strategies in corruption would have been modelled taking advantage of those

weaknesses. Thus efforts to improve transparency and accountability, as well as the

strength of the regulatory regime in curbing corruption have a huge probability of success

if the private sector views are taken into account. Similarly, it is the private sector that is

more suited to expose the various economic opportunities for which corruption is being

used as a tool to exploit. Thus the importance of the private sector as a player in anti-

corruption efforts can not be trivialized, and a strategy is required to gather this

knowledge for use in the anti-corruption drive.

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

The most critical requirement is for companies to speak with one voice in the fight

against corruption. The business sector needs to look at itself first and put its house in

order before shifting attention to its corrupt counterparts from the public sector. The

private sector needs to own up to its critical role in promoting and sustaining corruption

in order to understand its need to play the most critical role in nipping the vice in the bud.

Corruption can easily be eradicated if players from the private sector refrain from

participating in corrupt activities. However the prisoner’s dilemma situation brought

about by the uncertainty on fellow competitors’ action makes this difficult. Thus

companies have to collectively make the decision, through open and transparent

commitments and pledges which can be easily monitored. This apparently implies that

companies have to engage in discussions among themselves to outline the numerous

benefits that accrue to the sector as a whole as a result of the movement of resources from

corrupt officials back into the business coffers. If companies can find means of sitting

together clandestinely to conspire against the consumers through illegal cartels despite

strict competition laws, it can surely not be difficult for competitors to have an open

meeting to fight corruption! Such meetings may be analogous to a cartel in the

‘corruption market’, the only difference being that this would be an anti-corruption cartel,

with no harm to consumers but to corruption.

It would be difficult for buy-in if such a platform is initiated by individual companies, but

it will not be difficult if existing structures that business already has in place, through

various associations and body representatives including association of small scale

enterprises, are used. Thus the existing structures would be used as the avenue through

which all inclusive anti-corruption meetings and actions would be devised and this can

work through the following process.

The bodies, through their own structures across the whole country, would each call up

meetings with their constituencies and discuss the various facets through which

corruption exists and some means of closing off these facets, which would form the basis

for collective action. All companies would therefore get opportunities to sit together and

outline the requirements for collective actions that can be undertaken to fight corruption.

Selected representatives from these bodies would become members of the Anti-

Corruption Business Committee, which would meet to discuss the collective action

strategies that each representative would table. The Committee would come up with

explicit steps and action plans for the collective action approach and identify all possible

concerns that have to be addressed for this to happen, including policy and paradigm

shifts on the part of the government and other stakeholders. Thus the objective of the

Committee would be to recommend strategies, acceptable to all players, which each

business unit can adopt to instil a corruption free culture into the economic activities. The

Committee would also fare better in soliciting views and first hand information on the

operation of the various corruption syndicates, with firms free to give the information

without fear of prosecution.

There is always a limit on the extent to which anti-corruption action by the private sector

on its own can succeed without the involvement of the other corrupt arm; the public

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

sector. Thus collective action by the private sector has to lead to incorporation of the

public sector; hence establishment of a platform where views of the public sector can be

discussed and harmonized is a crucial step. The same applies to other critical stakeholders

like civil society representatives and independent regulatory authorities, who can also

influence positively the anti-corruption efforts. Collective action by the business also has

higher chances for success if it receives buy-in from all the other stakeholders.

Thus the other task of the Committee therefore would be to play a critical role in

lobbying for the establishment of a National Anti-Corruption Reference Group (NARG),

which would include members from the Committee and representatives from the public

sector and civil society. This would also include members from the anti-corruption

authorities and competition authorities in addition to the policy makers to ensure intense

debate on corruption matters within the confines of other laws. The purpose of NARG

would be simply to ensure that the collective action approach taken by the business

receives a complementary response from other stakeholders whose action have an impact

in the corruption market. Thus NARG would discuss the merits for the various concerns

and recommendations made by the Committee and recommend complementary roles that

the players from the public sector and civil society can play in eliminating corruption.

The reference group would also make policy recommendations for the strengthening of

the regulatory regime governing corruption.

It is also important for a strategy to be developed to mobilise resources towards financing

of the various initiatives and meetings to enable the Committee to perform its task. This

might call for business to contribute to a fund in the event that donor support can not be

mobilised, whose proceeds would be used strictly to facilitate the collective action

programme. However, the contribution requirement has to be conscious of the different

sizes of companies. Thus it is important for companies themselves to agree on the mode,

preferably a fixed percentage linked to assets, turnover or profits, which can be paid as

contributions towards the fund. It would also be left to business to decide whether all

companies, including SMEs should contribute or there would be a size cut-off on eligible

companies. Government funding can also be sourced at the NARG stage.

Even though the Committee may fail to lobby for the formation of NARG, the collective

efforts by the business sector alone would have a chance of success if strategies are

developed to counter the pressure the public sector would continue to exert in seeking to

continue with the corruption drive. As NARG is outside the control of business, more can

still be done at the Committee stage as long as incentives can be developed to try and

discourage firms from cheating the agreed collective action norms. Thus in the event that

NARG fails to materialise, that should not be an excuse to ditch the collective action

approach.

4. Conclusion

Corruption is both demand driven and supply driven. While the public sector’s role in

facilitating corruption through demands for extra payments and facilitations outside the

normal payment schedules is well appreciated, the role of the private sector in offering to

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

indulge in corrupt activities as a way of beating competition can not be ignored. In

addition, while corruption among players from the public sector among themselves is

negligible, the same can not be said about corruption among private sector players on

their own. Thus, the most active participants in the corruption market are players from the

business sector.

Being the dominant players in the corruption market, no successful efforts towards the

elimination of corruption can be embarked on without involving the business sector.

Moreover, as they are the most corrupt player; action by the private sector that is not

imposed upon them but embarked upon at their initiation, will work best in eliminating

corruption. The call for collective action by the business in the fight against corruption is

therefore not misplaced.

Collective action towards a common objective of corruption elimination by the business

sector therefore has high chances of success. But for the call for collective action to be

imbibed, conviction is needed that it is in the interest of all stakeholders to pursue it.

Businesses have to be made aware of the numerous benefits of a corruption free society

to the business sector as a whole, and how it is in their interest to help in attaining it.

Such a collective action is also not without some short run costs to some companies; the

opportunity cost in terms of the potential to lose out contracts as a result of competition,

which corruption was being used to shield, may be real. However these are far

outweighed by the benefits to accrue to companies and the economy in general through

the elimination of corruption. Costs incurred in the collective action process, through

opportunity costs or directly, should therefore not be used as an excuse to shy away from

the process.

References

• Boehm, F (2007), ‘Regulatory Capture Revisited –Lessons from Economics of

Corruption’, Working paper, JEL: K42, L97, B52, D73.

• Clarke, G. R.G and Xu L C (2001), ‘Ownership, Competition, and Corruption:

Bribe Takers Versus Bribe Payers’, Journal of Economic Literature.

• IFI Anti-corruption Task Force (2006), ‘Uniform Framework for Preventing And

Combating Fraud and Corruption’, African Development Bank, Asian Development

Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development European Investment Bank,

International Monetary Fund, Inter-American Development Bank and World Bank.

• International Chamber of Commerce, Transparency International, the United Nations

Global Compact and the World Economic Forum Partnering Against Corruption

Initiative (2008), ‘The Business Case against Corruption’, (a joint publication).

• Mitra, S (2003) “Corruption as cascades”, Social Change, Volume 33, No. 4

• PricewaterhouseCoopers International (2008), ‘Confronting corruption: The business

case for an effective anti-corruption programme’, PricewaterhouseCoopers.

• World Bank Institute (2008), ‘Business Case for Collective Action Against

Corruption’, World Bank.

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

Cornelius Dube, April 2009

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- 2 Ricardian ModelДокумент51 страница2 Ricardian Modelkeshni_sritharan100% (1)

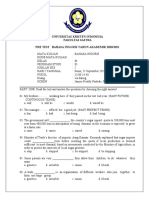

- Pre Test of Bahasa Inggris 21 - 9 - 2020Документ5 страницPre Test of Bahasa Inggris 21 - 9 - 2020magdalena sriОценок пока нет

- Strategic Management in Tourism 3rd Edition Chapter 3Документ9 страницStrategic Management in Tourism 3rd Edition Chapter 3Ringle JobОценок пока нет

- Steel CH 1Документ34 страницыSteel CH 1daniel workuОценок пока нет

- Daimler Chrysler MergerДокумент23 страницыDaimler Chrysler MergerAdnan Ad100% (1)

- Lesson 1 Business EthicsДокумент21 страницаLesson 1 Business EthicsRiel Marc AliñaboОценок пока нет

- Your Account Summary: Airtel Number MR Bucha Reddy AДокумент8 страницYour Account Summary: Airtel Number MR Bucha Reddy AKothamasu PrasadОценок пока нет

- Jagath Nissanka,: Experience Key Roles and ResponsibilitiesДокумент2 страницыJagath Nissanka,: Experience Key Roles and ResponsibilitiesJagath NissankaОценок пока нет

- Turquía 7.25% - 2038 - US900123BB58Документ61 страницаTurquía 7.25% - 2038 - US900123BB58montyviaderoОценок пока нет

- Comparative Analysis of Public & Private Bank (Icici &sbi) - 1Документ108 страницComparative Analysis of Public & Private Bank (Icici &sbi) - 1Sami Zama100% (1)

- Chapter One - Part 1Документ21 страницаChapter One - Part 1ephremОценок пока нет

- Economic History of The PhilippinesДокумент4 страницыEconomic History of The PhilippinesClint Agustin M. RoblesОценок пока нет

- 21936mtp Cptvolu1 Part4Документ404 страницы21936mtp Cptvolu1 Part4Arun KCОценок пока нет

- IBT-REVIEWERДокумент10 страницIBT-REVIEWERBrenda CastilloОценок пока нет

- Portfolio Management 1Документ28 страницPortfolio Management 1Sattar Md AbdusОценок пока нет

- FormatДокумент2 страницыFormatbasavarajj123Оценок пока нет

- Blades in The Dark - Doskvol Maps PDFДокумент3 страницыBlades in The Dark - Doskvol Maps PDFRobert Rome20% (5)

- Iraqi Dinar - US and Iraq Reached On Agreement To IQD RV - Iraqi Dinar News Today 2024Документ2 страницыIraqi Dinar - US and Iraq Reached On Agreement To IQD RV - Iraqi Dinar News Today 2024Muhammad ZikriОценок пока нет

- Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited: Price ListДокумент10 страницHindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited: Price ListVizag Roads33% (3)

- Optional Credit RemovalДокумент3 страницыOptional Credit RemovalKNOWLEDGE SOURCEОценок пока нет

- 1 Fmom - Basic Supporting DocumentДокумент50 страниц1 Fmom - Basic Supporting DocumentArnold BaladjayОценок пока нет

- Types of EntrepreneursДокумент32 страницыTypes of EntrepreneursabbsheyОценок пока нет

- Deed of Sale 2Документ6 страницDeed of Sale 2Edgar Frances VillamorОценок пока нет

- TCC Midc Company ListДокумент4 страницыTCC Midc Company ListAbhishek SinghОценок пока нет

- Annotated BibliographyДокумент9 страницAnnotated Bibliographyapi-309971310100% (2)

- Mark Scheme Economics Paper 2 Igcse 2020Документ23 страницыMark Scheme Economics Paper 2 Igcse 2020Germán AmayaОценок пока нет

- Book Building Process and Types ExplainedДокумент15 страницBook Building Process and Types ExplainedPoojaDesaiОценок пока нет

- Directory of Cao 01042018Документ154 страницыDirectory of Cao 01042018Shyam SОценок пока нет

- Solar Crimp ToolsДокумент4 страницыSolar Crimp ToolsCase SalemiОценок пока нет

- Fisker Karma Specs V2Документ1 страницаFisker Karma Specs V2LegacyforliveОценок пока нет