Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Design For Social Innovation As A Form of Designing Activism. An Action Format

Загружено:

NestaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Design For Social Innovation As A Form of Designing Activism. An Action Format

Загружено:

NestaАвторское право:

Design for social innovation as a form of designing activism. An action format.

Anna Meroni, Davide Fassi and Giulia Simeone Politecnico di Milano, Department of Design, POLIMI DESIS, Italy Social Frontiers The next edge of social innovation research

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

Main author: Title: Organisation: Country: Email address: Postal Address: Main author: Title: Organisation: Country: Email address: Postal Address: Main author: Title: Organisation: Country: Email address: Postal Address: Anna Meroni PhD, Assistant professor of service and strategic design Politecnico di Milano, Department of Design, Polimi DESIS Lab (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability) Italy anna.meroni@polimi.it via Durando 38a, 20158 Milano, Italy Davide Fassi PhD, Research fellow and professor of product-service-system design Politecnico di Milano, Department of Design, Polimi DESIS Lab (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability) Italy davide.fassi@polimi.it via Durando 38a, 20158 Milano, Italy Giulia Simeone PhD, Research fellow and professor of service design Politecnico di Milano, Department of Design, Polimi DESIS Lab (Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability) Italy giulia.simeone@polimi.it via Durando 38a, 20158 Milano, Italy

Keywords: Service Design, Design Activism, Creative Communities, Public Space, Food Systems Abstract This paper presents and discusses an in-progress action format developed through a reflection on several design experiments aiming to make things happen. It brings to the already rich debate on social innovation a designers perspective mainly focused on action research and field actions. It is an action format of design for social innovation, the Social Innovation Journey, structured on a non-linear sequence of steps and actions that progressively engage a community and help it to set up and prototype a social innovation. This happens through an event-like pilot initiative: a farewell initiative that, while prototyping the innovation, releases its full ownership to the community. The action format is illustrated through research projects and training activities which have brought designers to design with the social innovators, thats to say side by side with the them, in a pretty immersive way. The Social Innovation Journey is an open, in-progress, framework for intervention set up by the Polimi DESIS Lab, the Politecnico di Milano based laboratory of the international network DESIS Design for Social Innovation and Sustainability. It comprises a network of researchers adopting a strategic and systemic approach to design, with a specific focus on designing for services and design activism. It explores how design can enable people, communities, enterprises and organisations to kick off and manage innovation processes by co-designing and setting in place experiments of new services and solutions.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

1 Empowering Creative Communities Since the early 2000s, the international group of researchers and scholars in service and strategic design that, later, would found the DESIS network, started to investigate the phenomenon of creative communities: groups of people doing together small, creative, extraordinary things to change the way of living, so as to bring value to society, the environment and business. EMUDE Emerging User Demand for Sustainable Solution, a research funded in 2004-06 under the 6th FP of the European Commission was one the initial projects of the group (Manzini & Meroni 2007). From that moment on, the research to understand and then empower, through design, social innovators has never stopped. By integrating, more and more, researching and teaching, several applied research projects have been developed. With particular regard to the Polimi DESIS Lab, a few examples of activities are worth mentioning, in order to clarify the typologies of the interventions. This has resulted in growing experience in education and action research projects of design for social innovation: building on this experience, the Lab is today framing an action format that can guide further initiatives, be replicated and evolved. Roughly, the typologies of action can be classified as follows: educational activities developed in service design studios at the Masters level of design programmes: it is a kind of action research that, finding inspiration and commitment in existing or potential research projects, activates the students creativity and capacity to explore new possible areas of work. This is the case, for instance, of Yes Weekend!, a service design studio in 2012 with the students of the Master of Product Service System Design of Politecnico di Milano, to explore tourism in the periurban areas of the Parco Agricolo Sud of Milano, a huge agricultural piece of land bordering the city. Students were asked to co-design with farmers and citizens simple, workable and ready to use services to enable citizens to enjoy their weekend in the local farms. The activity was connected to the existing project Nutrire Milano Feeding Milan (www.nutriremilano.it), that will be presented later on, and resulted in 10 ideas that raised the consciousness of farmers and citizens about the potentiality of the area. Besides the educational purpose, these activities aim at opening up a conversation with selected stakeholders about potential research projects. 1 esearch activities developed through educational ones: it is a kind of action research r that engages students in parts of the projects, asking them to generate ideas that contribute to the general work. This is the case, for instance, of Human Cities, Reclaiming public space, a project supported by the Culture programme of the European Commission (in 2011-12) aimed at activating people and local stakeholders with regard to the public space. Students of the Master of Product Service System Design were involved in the task of designing initiatives and toolkits to enjoy the space of the Campus of the Politecnico di Milano in the neighbourhood of Bovisa, as it is, indeed, a public space (www.humancities.eu). The project resulted in a very good response from the people, which lead to the activation of the project Coltivando the convivial garden at the Politecnico di Milano that will be described later in this paper. This kind of activity, of which Human Cities is a paradigmatic example, is aimed at opening up opportunities for a more creative and exploratory research, thanks to the involvement of students. As for the previous kind of research, it might evolve into unexpected initiatives. research activities developed by professional researchers in response to projects: it is a kind of action research that is mainly managed by teams of experts with the occasional involvement of students. The knowledge produced, then, feeds both research and training. This is the case, for instance, for SPREAD-Sustainable Lifestyles 2050 a multidisciplinary European social platform project that developed a vision for sustainable lifestyles in 2050 (www.sustainable-lifestyles.eu). The design contribution focused on co-designing scenarios with experts and stakeholders, combining social and technological innovation, bottom-up and top-down approaches. This is a design driven approach, which aims at activating social conversations about future perspectives for individuals, communities, enterprises or any kind of private or public organisation.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

The previously mentioned cases illustrate the effort of design researchers to create and diffuse into society a culture of sustainable innovation by activating reactions that might reach beyond the purpose of the specific projects. In other words, by creating contexts for sharing of experience and practice (Ceschin 2012; Ehn 2008) that enable people to act in a more effective and professional way, a culture of social innovation might emerge. 2 Designer as an Activist Despite the academic context in which these research projects have originated, the approach adopted was, from the beginning, orientated to start processes to make things happen as soon as possible, by putting in place different forms of prototyping and learning from the related mistakes and failures (Brown, 2009). These processes have been conducted by applying service and strategic design tools in a trial and error manner: the main lessons learnt, nevertheless, are not only about the way methods and tools were used, but also are about the way designers approached the stakeholders and the community (Sanders & Stappers 2008; Margolin 2012). One of the first lessons learnt is that loyal dedication and deep diving into the social system are conditions of work for the designer dealing with social innovators. In doing this, the designer becomes part of the team or community attempting to undertake the challenge. Conventional professional advice is here replaced by a situation where the designer is embedded in the community. This allows speaking about design and community coaching: using professional tools to make things happen and enable people to do it (Fuad-Luke, 2009; Fry 2011). Another lesson learnt from the action research experiences is the importance of understanding in which phase of development the social innovations need to get support from designers and for how long it is required so as to make initiatives become self-sufficient and the community competent (Meroni & Sangiorgi 2011). This is a designerly way of intervening into peoples lives, motivating actions, mobilising stakeholders, creating spaces of contest, which reveal and challenge existing configurations and conditions of society (Markussen 2011). This is also a shift from designing for the community, to designing with the community and finally to allow communities to design by themselves (Brown 2009) and it opens up the issue of planning an exit strategy by creating the condition for the innovators to be autonomous and committed enough to take the initiatives further. Looking back at the research projects is an opportunity to reflect about the process, the outcomes and the interaction with the stakeholders, in order to frame an action format that can be further evolved and replicated for a more effective intervention. In the next section of this paper a draft of the Social Innovation Journey is presented, built upon the experience of Polimi DESIS Lab: it systematises activities recurring in the research projects and tries to help designers understand the stage of the social innovations they are dealing with and the potential of following ones. The method leads to the stage of incubation of a social enterprise. As such, it also helps to evaluate and plan the possible intervention according to the various steps. It is worth mentioning that, not being a linear process, it might have various iterations and requires the interaction of a variety of competences. With regard to the design action, in particular, the experiences developed so far have reached the stage of producing a prototype of a special kind. After that phase, on one hand the innovation is somehow released to the owner (either an individual, a group, a community, an enterprise) who might decide to evolve it as a kind of enterprise or replicable model, and on the other hand it needs the support of an incubator with specific skills. The special kind of prototype mentioned above is something that contributes to qualify and distinguish the method: it is, in fact, not a simple functional test of potential innovation, but is an engaging event (or sequence of events) which aims to activate the social innovators to move the initiative ahead and become independent of the designers. It is, in other words, a farewell action that must be carefully planned as a part of the exit strategy of the project. In the following sections the method will be discussed and exemplified through a couple of applied research projects, Coltivando and Nutrire Milano - Feeding Milan. As the method has been built on the experience of these projects (and others), there are occasional inconsistencies and divergences that represent the progress of the approach. Still, it will remain open to evolutions and adaptations according to the different circumstances. It has to be considered, therefore, as action format.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

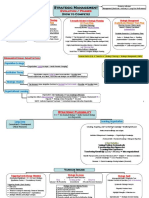

3 Fostering and Supporting Social Innovation: the Social Innovation Journey The Social Innovation Journey can be schematised as in figure 1: it visualises the different steps and the main possible interactions of the process.

Fig. 1: The in-progress Social Innovation Journey (Politecnico di Milano DESIS Lab)

Steps are phases of the development of social innovation (i.e. the degree of development and implementation of the idea) that allow the designer to understand the kind of action to take. We can assume that the passage from a phase to another is a form of up-scaling. Raise awareness Find and activate potential social innovators. This is an in-depth phase to be centred on the explicit or implicit awareness of the social innovators of their role and actions. It allows, in parallel, for light to be shed on hot topics. Awareness could be raised through direct contact with local initiatives and promoters, so as to present them with the possibility of supporting them through the design process/tools/output.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

Identify a topic for action Obtain the interest of an existing/potential community of social innovators and stakeholders. This step is about establishing direct contact with the community and developing a first phase of desk research that could support potential areas of interest. Interests could be then highlighted through a proposal by the designers and/or by the informal (or formal) communities themselves who have already framed the action. This step, often, follows the next one. Involve pro-active people & experts Define a vision and scenario. In this step, the most pro-active agents of the community (i.e. the social innovators) who might become the main stakeholders of the project or its driving force, have to be identified and involved to work side by side. This is a crucial step of designing for social innovation, as it implies not to start from scratch, as in a vacuum, but from the capacity and interest of people and groups already active in the specific field. This phase is aimed at framing a vision and a scenario for possible solutions, setting context-specific initiatives, and defining why and how to attract other potential stakeholders. This phase, finally, result in obtaining consensus by the community. Generate & select ideas Develop a first set of draft concepts. In this step, ideas are not yet defined into details but they present possibilities and opportunities to be further developed with a broader community of stakeholders. The generation process is a co-design one that involves (or takes into account the input of) the experts and the pro-active stakeholders, and uses the scenarios as a starting point for the conversation. Define timing, roles & exit strategy Create an action plan for the project. Despite the fact that this plan will be validated only after the next co-design activities and a clearer idea of the solutions, it is of great importance to draft it as soon as possible in the process, so as to carefully plan the use of the resources, the timespan of the project, the expertise, the activation of the stakeholders. As an outcome, the role of the designer has to be clear, as well as the exit strategy that might or might not coincide with the prototyping phase. This step might often anticipate the generation and selection of ideas. Co-design with broader communities Foster the social engagement. Attract additional stakeholders and start a process of engagement with the project. The co-design sessions organised within this step need to involve as many people as possible in order to ignite a social conversation about the ideas and get inputs back. Some of the people engaged in this phase would probably become ambassadors of the ideas within broader communities. By doing so, the ideas could continue to spread in the society and, hopefully, generate a movement that enables people to take action. Develop the solution: roles & rules Define the relationships between the stakeholders. After the co-design sessions, the action plan of the project could be then validated and set in place. In this step the components of the system are designed, including the hardware (i.e. spaces, objects, communication etc.) and the software (i.e. tools, platforms, rules to be followed etc.). At this end of this phase, the value proposition of the solution, its overall sustainability and the benefits for the different stakeholders must be clear. Produce an event-like prototype Involve the community in testing the solution in a way that creates the functional and emotional involvement and attract a broader audience. It might take, in reality, several actions and progressive experiments. It is intended to prove the practicability of the idea while creating an emotional engagement that enables and motivates the community to take full ownership of it, and pursue it over time. Meanwhile, the hardware of the system is tested so as to refine the solutions if needed.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

Take it to an incubator After the prototype phase the solution might be taken to an incubator in order to evolve it as a structured venture or as a start-up. The incubator brings the skills that are likely to be missed, until that phase, into the process: namely business planning, system engineering, market analysis and so forth. The incubator also helps the innovator to make a full assessment of the solution, so as to define its key performance indicators and the conditions for its overall sustainability. This is not a mandatory phase, but it is needed when the solution presents business possibilities and the innovator is keen to move in this direction. The venture might then take the shape of a social enterprise. The incubation provides inputs to re-shape the solution, to model the business, to start up the enterprise and replicate the initiative. When the solution upgrades to a real enterprise, it could be replicated in other contexts. 4 The Social Innovation Journey through Projects Two project developed by the Polimi DESIS Lab are then described in the section to present the implementation of the method. 4.1 Coltivando - The convivial garden at the Politecnico di Milano Coltivando is the community garden set up at the Politecnico di Milano - Bovisa Campus, a collaborative project where the competences of both spatial and product service system designers converged. It has been developed by a team of postgraduate students, supervised by researchers and teachers and co-designed with the local neighbourhood. www.coltivando.polimi.it

Fig. 2 Coltivando (Politecnico di Milano)

Raise awareness Within the framework of the European Research Human Cities, the Polimi DESIS Lab investigated how to open the public space (with considerable green areas) of the Politecnico di Milano - Bovisa Campus to the neighbourhood and the city. This was meeting the needs of the neighbourhood of reclaiming a public space that was part of their culture, since the campus is located in the site of a former manufacture where most of the people living there were working.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

Identify a topic for action In October 2011, after a weeklong workshop held by the Polimi DESIS Lab at the School of Design of Politecnico di Milano, 9 different actions were presented by the students to reconnect the neighbourhood and the campus. They were tested and prototyped during a one-day event: C spazio per tutti - Theres room for everyone. One of these actions was about the creation of a community vegetable garden. It was the most successful one, and many people working at the university and living near the campus showed interest in being a member of the future community garden. Involve pro-active people & experts The results of the previous phases were then taken in consideration by the Polimi DESIS Lab in February 2012. This brought together a team of multi-disciplinary students, staff with expertise in spatial design and service design, a local association involved in community garden (Il Giardino degli Aromi) and the Milanese network of them (Libere Rape Metropolitane) plus a community garden and development practitioner from an Australian social enterprise (Urban Reforestation), so to create a group of experts and pro-active people to develop the project of the garden. Generate and select ideas Since there was room and interest to engage the Politecnico di Milanos students, staff and surrounding community with the public space in the campus, a convivial model was defined as possible answer to the need of having a garden: the gardens vegetables would have grown and then distributed in a shared, communal, way. Spatial and service designers generated ideas to be discussed with the community in co-design activities, so as to better understand how the hardware (beds, shelters, etc.) and the software parts (rules, management, etc.) of the garden could be developed. Define timing, roles & exit strategy These first ideas including a plan of development of the project (to be confirmed after the codesign workshop) and the different roles of the stakeholders involved (researchers, students, associations, citizens) were put in place. In the specific case, due to the location and nature of the project, the exit-strategy of the designers (thats to say the way of releasing of the solution in the hands of the community) was not planned, but the idea was to support the project until its self sufficiency in terms of organization. Co-design with broader communities The team of designers organised workshops to co-design the community garden with its potential users. This has been an important phase of the project because the users of the garden will be giving feedback to the designers on how they think it should look like. Three community consultation sessions were run: 1. May, 2012. An internal meeting with the students and staff of the university to engage them in the project. The aim of this workshop was twofold: from one side, it aimed at informing the academic community about the garden and to collect their feedbacks according to the peculiar expertise; on the other side, the hope was to involve more design disciplines in the project, such as communication, fashion and product. May, 2012. A first external meeting with the local community to spread the word about the project as well as to co-design different elements of the garden with them. The co-design activities focused on the creation of groups of expert and beginner gardeners; they were asked to design the map of the garden, according to some given elements (such as: plants, benches, bushes, tools, convivial spaces); then they were asked to discuss a draft of the membership basic rules. June, 2012 As well as the first co-design workshop, after one month designers replicate it to engage more people from the neighbourhood.

2.

3.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

4.

At the end of the two co-design session, more than 80 people from the neighbourhood were involved and some of them actively took part to the next steps of the process.

Develop the solution: roles & rules Designers collected from the workshops feedbacks to give a final shape to the garden space, as well as to the service model and the garden governance. They put the basis for the first community and for the garden construction in October 2012. As a demonstration to the people of the co-design session, spatial designers build the prototype of the Box Zero, the container for the plants specifically designed for Coltivando and put some tomatoes and basils in it. It was aimed at testing the effectiveness of the box project, as well as to prove the actual interest of the local people in volunteering to take care of the box in the summertime. Produce an event-like prototype On October 13th 2012, the second edition of C spazio per tutti- Theres room for everyone event was held. At this time, students and designers were still working on the event that will last for one week and will end on October, 13th, with the collective construction of the first garden bed, as well as the first community of 25 people. Colivando was not taking into an incubator and it didnt follow the Social Innovation Journey in its complete cycle. The event-like prototype was the starting point for a weekly appointment engaging people on building both the site and the group. This process of affection is still going on and makes emerge some adjustments compared to projects that came out from the previous phase. Coltivando is now a place where people are enjoying their free time, producing their own vegetables and fruits and enriching their social experiences through collateral activities i.e. seminars, schools visits etc.

Fig. 3: the Social Innovation Journey for Coltivando (Politecnico di Milano)

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

10

4.2 Nutrire Milano Feeding Milan: Energy for Change Feeding Milan: Energy for Change is an action research project funded by Fondazione Cariplo, a bank foundation, and developed by a partnership between Slow Food Italia, the Polimi DESIS Lab and the Universit di Scienze Gastronomiche. Started in 2010 and now, in 2013, near to the conclusion, it investigates how design for social innovation can contribute to create a local foodshed that serves to connect local food production in periurban areas (and in particularly in the huge agricultural park bordering the south of the town, the Agricultural Park South) with its consumers in town, through a network of services (Manzini & Meroni 2013; Cant & Simeone 2011). Given that it actually encompasses a number of different services, the following description will focus only on some specific ones and on the framework project. As consequence of its complexity, the project implied several iterations and parallel activities. www.nutriremilano.it

Fig. 4: Feeding Milan (Politecnico di Milano)

Raise awareness In 2007, a small fund from the Italian Ministry of the University and the Research allowed the Polimi DESIS Lab to start a theoretical research about the role of agricultural parks for the sustainable development of regions and towns. It was the opportunity to investigate the reality of the Agricultural Park South of Milano. Partially involving the students of the School of Design of Politecnico, the research resulted in the creation of a scenario for a regional foodshed, combining production and leisure in a network of new short-chain services. It was also the opportunity to get in touch with local stakeholders (authorities, farmers, organisations) already active in the region and operating with this purpose. Identify a topic for action In 2009, when the city of Milan won the competition to host the Expo2015 proposing a food related topic (Feeding the Planet. Energy for Life is the title), the DESIS Lab and the Slow Food association (already collaborating in other activities) decided to conceive a project that, despite any possible initiative of the board of the Expo, would have elaborated and put in place a vision of food sustainability and sovereignty for the city of Milano.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

11

Involve pro-active people & experts The partnership of the DESIS Lab with Slow Food and with the University of Gastronomic Sciences was informally set: in a few weeks, a first vision, an articulated scenario and a detailed project plan were prepared, with the aim of looking for funding. After a few months the financial support was found: an initial grant from Cariplo Foundation was defined, and the partnership officially started to work. The common purpose was making things happen as soon as possible. As the project begun in its general frame and the ideas for specific services where generated, the same activity of involving experts and pro-active stakeholders was repeated for each service in different phases. Generate and select ideas Beginning fall 2010, a co-design workshop was organised between the Polimi DESIS Lab, the Slow Food and the University of Gastronomic Sciences teams in order to move form the scenario to specific services in the field, using existing assets, resources and people. Specific design tools (ideas cards, case studies, etc.) were produced for the purpose of stimulating the brainstorming. A first set of ideas were generated and agreed to be further developed. Among those, the farmers market. Meanwhile, some pivotal editions of the farmers market were set in place, adopting the format of the Earth Markets, the Slow Food concept for it. Define timing, roles & exit strategy A more detailed plan of actions was then defined, targeting 2015 as first scenario for having a number of initiatives in place. Specific roles were set for the research partners, and other specific partners, experts or collaborators were involved. Since the funding scheme was yearly approved by the Cariplo Foundation according to the results of the previous work, it was not possible to plan all the activities with accuracy. Moreover, being at that time the design process still in development and the experience not yet mature, a clear exit strategy wasnt set and this made the use of the resources not as effective as it could be. Co-design with broader communities In December 2010, after around one year from the beginning of the project, the full scenario of Feeding Milan and the outcomes already in place were presented during an open, bold, event organised by the research partnership and the Foundation and open to everybody. For the purpose of that event, a catching storytelling of the scenario and the main service ideas were produced, designing a series of short movies named video-scenarios. It was the beginning of diverse co-design sessions organised in several circumstances to start a technical and social conversation about the project and its specific outcomes. According to the timetable of the design of the various services, open co-design sessions were organised in events, conferences, places and whatever useful circumstance the project partners were involved in. Most of all, the Farmers Market itself was an ice-breaking devise to make the whole project become tangible and reliable in the eyes of a broader community. It is worth mentioning, in particular, the Ideas Sharing Stall at the Farmers Market: a stall, among the others, conceived as an interaction point between the designers and the citizens/farmers/ producers potentially interested in the development of the services. At the stall, every time, a different topic for interaction and co-design was proposed.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

12

Develop the solution: roles & rules The specific services creating the network of Nutrire Milano had different timetables and plans of development. For each one, specific stakeholders were involved, different target identified and codesign sessions accordingly organised. Each one went through diverse generation and development phases, very often involving the students of the Master of Product Service System Design as active participants. Main services designed are the Farmers Market, the Farmer Food Box, the Local Bread Chain, the Local Tourism, the Local Distribution System. Produce an event-like prototype Considering the complex articulation of the project, the already mentioned lack of a detailed planning and a related exit strategy, the timespan of prototyping was different from one service to another. The Farmer Food Box, for example, went through 2 main cycles of prototyping, each one involving many people. It can be criticised that none of them was planned enough to effectively engage the main stakeholders and let them take the full ownership of it. Therefore, the solution still needs to fix several issues. The Farmers Market, instead, was successful to the extent that, when it was moved from one neighbourhood into another, a huge group of citizens started an action toward the public administration to have it back. Even if this action was not successful, it was the beginning of another story that the Polimi DESIS Lab begun in the neighbourhood in order not to waste the positive energy of the inhabitants. As an outcome, thus, the activism of the project team mobilised the people and really empowered the existing of prospective social innovators.

Fig. 5: the Social Innovation Journey for Feeding Milan. (Politecnico di Milano)

5 Next Steps: Discussion and Thinking About the Future The Social Innovation Journey is not a foolproof method to be replicated here and there to make things happen. It is, instead, an in-progress first attempt to guide the designer in understanding the different phases and statuses of a social innovation. In fact, by attempting to formalise the various, typical and recurring, phases of development of a social innovation, it helps also in defining the expected outcomes of each one and how the designer can act to help achieving them. A couple of general reflections can be, so far, presented. First, we can say that it is a design-led method, in the sense that it assumes the role of the designer as an early promoter of the ideas, often in conjunction with other pro-active subjects involved in the project. In other words, in the experiences so far matured by the Polimi -DESIS Lab, designers have had the role of provoking and steering, in a way, the debate around an idea by providing initial creative inputs and sacrificial concepts (Brown, 2009). Second, we can observe that the co-design activities conducted along the journey can be classified in two ways: an in depth co-design activity with selected stakeholder, pro-active subjects and experts, aiming at precisely developing the ideas; and an extensive, quick, co-design activity with wider communities of potential users/innovators aiming at getting feedback about ideas and, most of all, producing social engagement, as this is crucial for social innovation. Over the next months, the Polimi DESIS Lab will test, elaborate and evolve the method in research and training projects, in order to assess it.

Social Frontiers

Design for Social Innovation as a form of Design Activism: An action format.

13

6 References

Fuad-Luke, A 2009, Design Activism: Beautiful Strangeness for a Sustainable World, Earthscan, London. Fry, T 2011, Design as Politics, Berg, New York Brown, T 2009, Change by Design, HarperCollins, New York. Ceschin, F 2012, Critical factors for implementing and diffusing sustainable product-Service systems: insights from innovation studies and companies experiences. Journal of Cleaner Production, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.05.034, pp. 1-15 Ehn, P 2008, Participation in design things. In Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design 2008 (PDC 08), eds. D. Hakken, J. Simonsen, T. Robertson T. Bloomington, pp. 92-101 Markussen, T 2011, The disruptive aesthetics of design activism: Enacting design between art and politics. In Making Design Matter!: Proceedings of the 4TH Nordic Design Research Conference, eds I. Koskinen, T. Hrksalmi, R. Maz, B. Matthews, JJ. Lee, Helsinki, pp. 102-110 Manzini, E & Meroni, A 2007, Emerging User Demands for Sustainable Solutions, EMUDE, in Design Research Now: Essays and Selected Projects, ed. R. Michel, Birkhuser, Basel, pp. 157-185 Manzini, E & Meroni, A 2013, Design for territorial ecology and a new relationship between city and countryside. The experience of the Feeding Milan project. In The handbook of sustainable design, eds. S. Walker, J. Giard, Berg Publishers, Oxford. Margolin, V 2012, Design and Democracy in a Troubled World. Lecture at the School of Design, Carnegie Mellon University, April 11 Meroni, A 2013, An inventory of creativity necessary for the future, Inventario, n.07, pp. May, pp. 132-145 Meroni, A & Sangiorgi, D 2011, Design for Services, Gower Publishing Limited, Farnham. Sanders, E & Stappers, P 2008, Co-creation and the new landscapes of Design, Codesign, 4(1), pp. 5-18 Simeone, G & Cant, D 2011, Feeding Milan. Energies for change. A framework project for sustainable regional development based on food demediation and multifunctionality as Design strategies, In Young Creators For Better City & Better Life: proceedings of the Cumulus Shanghai Conference, eds. Y. Lou, X. Zhu. Shanghai, pp. 457-463

Sitography

www.coltivando.polimi.it www.desis-network.org www.humancities.eu www.nutriremilano.it www.sustainable-lifestyles.eu

Вам также может понравиться

- Design Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and ShowroomОт EverandDesign Research Through Practice: From the Lab, Field, and ShowroomРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (7)

- Zeisel John - Chs 1, 2 Inquiry by Design (1984)Документ34 страницыZeisel John - Chs 1, 2 Inquiry by Design (1984)mersenne2Оценок пока нет

- This Study Resource Was: AnswerДокумент2 страницыThis Study Resource Was: Answerteme beya100% (2)

- Transportation and Sustainable Campus Communities: Issues, Examples, SolutionsОт EverandTransportation and Sustainable Campus Communities: Issues, Examples, SolutionsОценок пока нет

- DesignEthnography MacNeilДокумент37 страницDesignEthnography MacNeilAldo R. AlvarezОценок пока нет

- The Impact of National Design Policies On Countries CompetitivenessДокумент24 страницыThe Impact of National Design Policies On Countries CompetitivenessmiguelmelgarejoОценок пока нет

- User Experience in the Age of Sustainability: A Practitioner’s BlueprintОт EverandUser Experience in the Age of Sustainability: A Practitioner’s BlueprintРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- Building The Digital Talent PipelineДокумент28 страницBuilding The Digital Talent PipelineNesta100% (1)

- Interview Question AnswersДокумент2 страницыInterview Question AnswersSushilSinghОценок пока нет

- Design and Social ImpactДокумент41 страницаDesign and Social Impactchriskpeterson100% (2)

- For Social Innovation: Author Kyriaki PapageorgiouДокумент72 страницыFor Social Innovation: Author Kyriaki PapageorgiouMonica Grau SarabiaОценок пока нет

- Architecture As Human InterfaceДокумент201 страницаArchitecture As Human InterfaceziadaazamОценок пока нет

- Youth Innovation CenterДокумент4 страницыYouth Innovation CenterSanjanaОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Public Participation in Spatial PlanningДокумент34 страницыGuidelines For Public Participation in Spatial PlanningSadije DeliuОценок пока нет

- Close Encounters With BuildingsДокумент7 страницClose Encounters With BuildingsAdrian TumangОценок пока нет

- Reyner Banham - A Throw-Away AestheticДокумент4 страницыReyner Banham - A Throw-Away AestheticclaudiotriasОценок пока нет

- Mapping Design Research at RMITДокумент41 страницаMapping Design Research at RMITPeter ConnollyОценок пока нет

- Design for Social Innovation: An Interview With Ezio ManziniДокумент8 страницDesign for Social Innovation: An Interview With Ezio Manzini1234embОценок пока нет

- A Meta-Theoretical Structure for Design TheoryДокумент21 страницаA Meta-Theoretical Structure for Design TheoryOscarОценок пока нет

- Literature Collection For Universal DesignДокумент43 страницыLiterature Collection For Universal DesignRiddhi Sanghvi100% (1)

- Design ThinkingДокумент25 страницDesign Thinkingnathalie13991Оценок пока нет

- Manzini - Design Culture and Dialogic Design - 2016Документ9 страницManzini - Design Culture and Dialogic Design - 2016Alberto PabonОценок пока нет

- Proportions and Cognition in Architecture and Urban Design: Measure, Relation, AnalogyОт EverandProportions and Cognition in Architecture and Urban Design: Measure, Relation, AnalogyОценок пока нет

- Design Informed: Driving Innovation with Evidence-Based DesignОт EverandDesign Informed: Driving Innovation with Evidence-Based DesignОценок пока нет

- Toolkit For Social InnovationДокумент396 страницToolkit For Social InnovationWauters BenedictОценок пока нет

- Education Eeuu PDFДокумент446 страницEducation Eeuu PDFWilson Andres Laguna GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Participatory Urban Planning: Bringing People Into the ProcessДокумент346 страницParticipatory Urban Planning: Bringing People Into the ProcessSlađana RadovanovićОценок пока нет

- Co-designing Infrastructures: Community collaboration for liveable citiesОт EverandCo-designing Infrastructures: Community collaboration for liveable citiesОценок пока нет

- Design Things and Design Thinking PDFДокумент16 страницDesign Things and Design Thinking PDFpceboliОценок пока нет

- Architecture As MATERIAL CULTURE PDFДокумент13 страницArchitecture As MATERIAL CULTURE PDFArqalia100% (1)

- Innovation Urban Mobility en 0Документ28 страницInnovation Urban Mobility en 0fuggaОценок пока нет

- A Social Model of Design - p24 - SДокумент7 страницA Social Model of Design - p24 - SevaclarensОценок пока нет

- Placemaking in The Digital AgeДокумент23 страницыPlacemaking in The Digital AgeSakthiPriya NacchinarkiniyanОценок пока нет

- 36 - Democratising GD Full PaperДокумент14 страниц36 - Democratising GD Full PaperKate Chmela-JonesОценок пока нет

- Illuminating-Natural Light in Residential Architecture (Art Photo)Документ232 страницыIlluminating-Natural Light in Residential Architecture (Art Photo)Cao Nhăn ĐứcОценок пока нет

- IDEO HCD Toolkit PreviewДокумент17 страницIDEO HCD Toolkit Previewkatieclark6Оценок пока нет

- Analyzing Design Review ConversationsОт EverandAnalyzing Design Review ConversationsRobin S. AdamsОценок пока нет

- BUCHANAN - 1992 - in Design Thinking Wicked Problems PDFДокумент18 страницBUCHANAN - 1992 - in Design Thinking Wicked Problems PDFleodeb1Оценок пока нет

- Cincinnati Form Based Code - FinalDraft - Web PDFДокумент245 страницCincinnati Form Based Code - FinalDraft - Web PDFlakshmisshaji100% (1)

- Spaces of Capital/Spaces of Resistance: Mexico and the Global Political EconomyОт EverandSpaces of Capital/Spaces of Resistance: Mexico and the Global Political EconomyОценок пока нет

- Humanitarian Design Response To CrisisДокумент18 страницHumanitarian Design Response To CrisisKreativeButterfly100% (1)

- Placemaking As An Approach of Sustainable Urban Facilities ManagementДокумент2 страницыPlacemaking As An Approach of Sustainable Urban Facilities ManagementKeziahjan ValenzuelaОценок пока нет

- Public Places and Spaces. An ProspectiveДокумент328 страницPublic Places and Spaces. An ProspectiveArturo Eduardo Villalpando FloresОценок пока нет

- Jane Jacobs: Mother of Modern Urban PlanningДокумент12 страницJane Jacobs: Mother of Modern Urban PlanningRini Sebastian0% (1)

- A Guide To Making Massive Small Change PDFДокумент62 страницыA Guide To Making Massive Small Change PDFOrestis MichelakisОценок пока нет

- 2011 Productive Public Spaces Placemaking and The Future of CitiesДокумент35 страниц2011 Productive Public Spaces Placemaking and The Future of CitiesAstrid PetzoldОценок пока нет

- How To Make Design BriedfДокумент4 страницыHow To Make Design BriedfNicole Verosil100% (1)

- Behind The Postmodern FacadeДокумент360 страницBehind The Postmodern Facadekosti7Оценок пока нет

- Lectura1 - IDEO - Design Thinking For Social InnovationДокумент4 страницыLectura1 - IDEO - Design Thinking For Social InnovationRossembert Steven Aponte CastañedaОценок пока нет

- DRS2018 Vol 4Документ506 страницDRS2018 Vol 4Muireann McMahon & Keelin Leahy100% (3)

- Designing Interactions - Bill MoggridgeДокумент5 страницDesigning Interactions - Bill MoggridgemazozihuОценок пока нет

- Ezio-Manzini-Design, Social Innovation and SustainableДокумент62 страницыEzio-Manzini-Design, Social Innovation and SustainablejannaynaОценок пока нет

- Design History's Role in Understanding the Development of DesignДокумент18 страницDesign History's Role in Understanding the Development of DesignlluettaОценок пока нет

- Neighbourhood Planning ResearchДокумент69 страницNeighbourhood Planning ResearchJon HerbertОценок пока нет

- Harnessing China's Commercialisation EngineДокумент48 страницHarnessing China's Commercialisation EngineNesta50% (2)

- Social Science Parks - Society's New Super LabsДокумент13 страницSocial Science Parks - Society's New Super LabsNestaОценок пока нет

- Internet As Common or Capture of Collective IntelligenceДокумент46 страницInternet As Common or Capture of Collective IntelligenceNestaОценок пока нет

- CITIE - The Nordic AnalysisДокумент25 страницCITIE - The Nordic AnalysisNestaОценок пока нет

- Innovation Policy Toolkit: Introduction To The UK Innovation SystemДокумент37 страницInnovation Policy Toolkit: Introduction To The UK Innovation SystemNestaОценок пока нет

- Flipped Learning - Using Online Video To Transform LearningДокумент42 страницыFlipped Learning - Using Online Video To Transform LearningNesta0% (1)

- When A Movement Becomes A PartyДокумент53 страницыWhen A Movement Becomes A PartyNestaОценок пока нет

- Collective Intelligence Framework in Networked Social MovementsДокумент81 страницаCollective Intelligence Framework in Networked Social MovementsNesta100% (1)

- D-CENT - Research On Digital Identity EcosystemsДокумент143 страницыD-CENT - Research On Digital Identity EcosystemsNestaОценок пока нет

- Longitude Prize - Infectious FuturesДокумент52 страницыLongitude Prize - Infectious FuturesNestaОценок пока нет

- Skills of The Datavores: Talent and The Data RevolutionДокумент52 страницыSkills of The Datavores: Talent and The Data RevolutionNestaОценок пока нет

- The NHS in 2030 - A People-Powered and Knowledge-Powered Health SystemДокумент48 страницThe NHS in 2030 - A People-Powered and Knowledge-Powered Health SystemNestaОценок пока нет

- Making Digital Work - AccessibilityДокумент16 страницMaking Digital Work - AccessibilityNestaОценок пока нет

- Collective Intelligence in Patient OrganisationsДокумент51 страницаCollective Intelligence in Patient OrganisationsNestaОценок пока нет

- Collective Intelligence - How Does It Emerge?Документ23 страницыCollective Intelligence - How Does It Emerge?NestaОценок пока нет

- D-CENT Managing The Commons in The Knowledge EconomyДокумент111 страницD-CENT Managing The Commons in The Knowledge EconomyNestaОценок пока нет

- Making Digital Work: DataДокумент16 страницMaking Digital Work: DataNestaОценок пока нет

- Impact Measurement in Impact InvestingДокумент23 страницыImpact Measurement in Impact InvestingNestaОценок пока нет

- Making Digital WorkДокумент150 страницMaking Digital WorkNestaОценок пока нет

- Machines That Learn in The Wild: Machine Learning Capabilities, Limitations and ImplicationsДокумент18 страницMachines That Learn in The Wild: Machine Learning Capabilities, Limitations and ImplicationsNestaОценок пока нет

- CITIE: A Resource For City LeadershipДокумент60 страницCITIE: A Resource For City LeadershipNestaОценок пока нет

- Investing in Innovative Social Ventures: A Practice GuideДокумент42 страницыInvesting in Innovative Social Ventures: A Practice GuideNestaОценок пока нет

- Nesta Annual Review 2015Документ42 страницыNesta Annual Review 2015Nesta100% (1)

- D-CENT: Design of Social Digital CurrencyДокумент59 страницD-CENT: Design of Social Digital CurrencyNestaОценок пока нет

- Rethinking Smart Cities From The Ground UpДокумент72 страницыRethinking Smart Cities From The Ground UpNestaОценок пока нет

- EDHEC 10-2021 - Strategy (1108) - Answers To Real Options PartДокумент7 страницEDHEC 10-2021 - Strategy (1108) - Answers To Real Options PartSASОценок пока нет

- Recruitment and SelectionДокумент44 страницыRecruitment and SelectionRahmatullah PashtoonОценок пока нет

- PT Trakindo Utama: QuotationДокумент3 страницыPT Trakindo Utama: QuotationANISОценок пока нет

- First Things First (1964 & 2000)Документ5 страницFirst Things First (1964 & 2000)MarinaCórdovaAlvésteguiОценок пока нет

- Transcript From The Interview of Atty. Casiano S. Retardo, Jr.Документ1 страницаTranscript From The Interview of Atty. Casiano S. Retardo, Jr.Aure ReidОценок пока нет

- Delta Programmable Logic Controller DVP Series: Automation For A Changing WorldДокумент52 страницыDelta Programmable Logic Controller DVP Series: Automation For A Changing WorldelkimezsОценок пока нет

- Developing an Employment Vocabulary. 7thДокумент18 страницDeveloping an Employment Vocabulary. 7thzoya maryamОценок пока нет

- Request For Permanent WorkДокумент2 страницыRequest For Permanent WorkNirmal BandaraОценок пока нет

- Generating FunctionДокумент14 страницGenerating FunctionSrishti UpadhyayОценок пока нет

- Jetronics IndiaДокумент17 страницJetronics IndiaShikha TОценок пока нет

- Introduction to Entrepreneurship FundamentalsДокумент11 страницIntroduction to Entrepreneurship FundamentalsJearim MalicdemОценок пока нет

- FM - Hosp - Tutorial 5Документ7 страницFM - Hosp - Tutorial 5Sylvia AnneОценок пока нет

- Proof of Cash CelticsДокумент3 страницыProof of Cash CelticsCJ alandyОценок пока нет

- Critical Thinking Exercise: Page 216, Industrial Relations, C. S. Venkata RamanДокумент23 страницыCritical Thinking Exercise: Page 216, Industrial Relations, C. S. Venkata RamanPardeep DahiyaОценок пока нет

- PDBM Fundemental Research AssignmentДокумент5 страницPDBM Fundemental Research AssignmentNtokozo VilankuluОценок пока нет

- AUD 1206 Case Analysis RisksДокумент2 страницыAUD 1206 Case Analysis RisksRОценок пока нет

- Management ScienceДокумент3 страницыManagement ScienceMario HernándezОценок пока нет

- Simu't Sarap in A CupДокумент3 страницыSimu't Sarap in A CupMARY JEANELОценок пока нет

- Muhammad Imran Technical KarachiДокумент5 страницMuhammad Imran Technical KarachiBDO3 3J SolutionsОценок пока нет

- ITC LimitedДокумент16 страницITC LimitedSANJANA BHAVNANIОценок пока нет

- Strategic Management - Chapter (1) - Modified Maps - Coloured - March 2021Документ4 страницыStrategic Management - Chapter (1) - Modified Maps - Coloured - March 2021ahmedgelixОценок пока нет

- Bobcat Compact Excavator E16 Operation Maintenance Manual 6989423Документ14 страницBobcat Compact Excavator E16 Operation Maintenance Manual 6989423andrewshelton250683psa100% (67)

- Ripken Products A Case For Learning Activity-BasedДокумент11 страницRipken Products A Case For Learning Activity-BasedLuisОценок пока нет

- Bartertrade - Io - WhitepaperДокумент41 страницаBartertrade - Io - WhitepaperRandall FlaggОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurship (MGT602) Fall 2020 Assignment No.02 Topic: The Importance of Entrepreneurship BackgroundДокумент2 страницыEntrepreneurship (MGT602) Fall 2020 Assignment No.02 Topic: The Importance of Entrepreneurship BackgroundjenniferОценок пока нет

- Chapter 8 Entry Strategies in Global BusinessДокумент3 страницыChapter 8 Entry Strategies in Global BusinessMariah Dion GalizaОценок пока нет

- Bizhub 40P: Designed For ProductivityДокумент4 страницыBizhub 40P: Designed For ProductivityionutkokОценок пока нет

- Case Study On Failure of Kellogg's in IndiaДокумент10 страницCase Study On Failure of Kellogg's in IndiaPUSPENDRA RANAОценок пока нет