Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Borrowing From Peter To Sue Paul - Legal

Загружено:

Christie SmithИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Borrowing From Peter To Sue Paul - Legal

Загружено:

Christie SmithАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

NOW

CITY BAR CENTER CLE WRITTEN

MATERIALS ARE AVAILABLE ON WESTLAW!

City Bar Center for CLE ofers more than 150 live, discrete CLE courses every year. Tese

courses are presented by leading subject-area experts from law frms, corporations, investment

banks, regulatory agencies, academia, and the Bench.

City Bar Center CLEs are national in scope and cover a wide variety of practice areas. City Bar

Center for CLE takes pride in the fact that they ofer courses in core practice areas such as corporate &

securities, as well as niche and emerging areas including fashion law, art succession for estate

planning, and the uses of mobile technology for lawyers.

Whether you are an experienced attorney seeking to refne your skills or a newly admitted attorney

working to build your career foundation, City Bar Center for CLE materials ofer the practical

guidance and strategies you need.

Accessing portions of our materials on Westlaw ofers countless advantages, among them:

- Te ability to search course materials using West proprietary search technology and

quickly focus on the topics that interest you within each course publication

- An opportunity for deeper analysis and increased knowledge in a wide-range of practice

areas

- 24/7 access to the course materials allowing for continuous review

New course materials are added to Westlaw on an ongoing basis.

*Tese course materials do not provide credit towards your states minimum CLE

requirements.

PASSPORT OPTIONS

Choose from:

- Unlimited registration to attend our 150 annual, discreet live programs as well as video replays for a twelve

month period from the date of purchase. A trial membership can be arranged for a period of six months.

- Firms can also purchase our live web casts and online programs through Casemaker

- As a stand alone or as an add on frms can purchase our DVDs with the materials. Te City Bar Center for CLE will

handle all administrative aspects of the CLE accreditation for the attorneys that view the programs.

PROGRAMS

A City Bar passport provides a wide array of programs in virtually every practice area. Te City Bar ofers a plethora of

programs in areas such as Corporate/Securities, Intellectual Property, Estate Planning, Employee Benefts, Labor and

Employment law, Insurance, ADR/Arbitration/Mediation/Negotiation, Real Estate, Tax and Accounting, Energy,

Matrimonial, Consumer Protection, Litigation, etc. We also ofer more ethics programs than other providers and the

programs are both general ethics and practice area specifc. A frm with multiple practice areas is well suited with a City Bar

passport. Our format of shorter, focused programs allows attorneys to earn their credits, learn what they need and spend

time in the ofce. Our Institutes provide excellent networking opportunities.

PROFESSION DEVELOPMENT SERIES

A passport enables frms to also attend programs from our Professional Development Series which are sponsored by frms

and geared towards sof skills training for mid level associates.

SPEAKING OPPORTUNITIES

Many attorneys from frms with passports speak at the programs. Tere is a strong connection with the frms when they

purchase passports.

SATISFACTION GUARANTEED

Our frm passport members have been very satisfed with the program and renew each year.

... the quality of the programs is consistently frst-rate and has resulted in our renewing our

Passport each year. I ofen receive calls from attendees afer they return from a program, telling

me how useful it was... We feel that the subject matters covered enable a broad cross-section of our

practices in New York to take advantage of the Passport. And, the Center is always receptive to

ideas for new programs...

Finally, the price is right. You get much more than you pay for.

Valerie Fitch, Director of Professional Development

Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP

PRICING

Our passport pricing is determined by the size of the frm/organization and previous usage. Our pricing is fexible.

FIRM PASSPORTS

CITY BAR CENTER FOR CLE

cle.nycbar.org

Mandatory CLE information

The City Bar Center for CLE is an accredited CLE provider in the States of New York, California, Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

For live programs, Illinois & Pennsylvania credits differ slightly as they are based on a 60 minute hour.

*You are required to sign in & out on the sign in sheet, indicating the times you arrive and leave.

** If you dont know your New Jersey Bar number you can call 609.984.2111 to obtain it.

*** As Pennsylvania is a paperless State we will not provide you with a CLE certificate. You can get proof of attendance by logging onto the

website, www.asapnexus.org, at least 30 days after the program you attended.

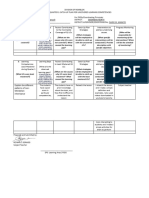

California Illinois New Jersey New York Pennsylvania

*Sign-In

Sheet

NY sign-in sheet IL sign-in sheet NY sign-in sheet NY sign-in sheet NY sign-in sheet

Include Bar

Number on

sign-in sheet

Yes Yes **Yes No Yes

Evaluation

Form

CA Activity Evaluation

Form

NY evaluation form NY evaluation form NY evaluation form NY evaluation form

CLE

Certificate

NY CLE Certificate with

CA Bar Number

IL CLE certificate NJ CLE certificate NY CLE certificate

***CLE certificate not

provided

Website www.calbar.ca.gov www.mcleboard.org www.judiciary.state.nj.us/cle www.nycourts.gov/admin/oca https://www.pacle.org/

Email or

Phone Number

888.800.3400 312.924.2420 609.984.2111

212.428.2105 (CLE)

212.428.2700 (General)

717.231.3230

cle.nycbar.org

The City Bar Center for CLE is an accredited CLE provider in the States of New York, California,

Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. For live programs, Illinois & Pennsylvania credits differ

slightly as they are based on a 60 minute hour.

Mandatory CLE Information

California: Sign-in and out on the New York sign-in sheet at the registration desk. Include your

California Bar number in the appropriate column on the sign-in sheet and we will include it on

your New York CLE certificate. Your CLE certificate will be available at the end of the

program. You are also required to hand-in a completed California Activity Evaluation form,

which will be available at the registration desk. For more information call 888.800.3400 or visit

their website, http://mcle.calbar.ca.gov.

Illinois: Sign-in and out on the Illinois sign-in sheet at the registration desk and include your

Illinois bar number. When you sign-out at the end of the program, your Illinois CLE certificate

will be available. When you sign-out, please make sure to hand-in your completed evaluation

form. For more information call 312.924.2420 or visit their website, http://www.mcleboard.org/.

New Jersey: Sign-in and out on the New York sign-in sheet at the registration desk and include

your New Jersey Bar number in the appropriate column. When you sign out at the end of the

program your New Jersey CLE certificate will be available. When you sign-out, please make

sure to hand-in your completed evaluation form. If you do not have your New Jersey Bar

Number, you can obtain it by calling (609) 984-2111. For more information visit their website,

http://www.judiciary.state.nj.us/cle/index.htm.

New York: Sign-in and out on the New York sign-in sheet at the registration desk. Your CLE

certificate will be available when you sign-out at the end of the program. When you sign-out,

please make sure to hand-in your completed evaluation form. For more information call the New

York Office of Court Administration at: 212.428.2105 (CLE information), 212.428.2700

(general information) or visit their website,

http://www.courts.state.ny.us/attorneys/cle/index.shtml.

Pennsylvania: Sign-in and out on the New York sign-in sheet at the registration desk and

include your Pennsylvania Bar number in the appropriate column. When you sign-out, please

make sure to hand-in your completed evaluation form. As Pennsylvania is a paperless State we

will not provide you with a CLE certificate. You can get proof of attendance by logging onto

www.asapnexus.org at least 30 days after the date of the program. For more information call

717.231.3230 or visit their website, www.pacle.org.

City Bar Center for Continuing Legal Education

THE NEW YORK CITY BAR

42 West 44th Street, New York, New York 10036

Borrowing from Peter to Sue Paul:

Legal & Ethical Issues in Financing a

Commercial Lawsuit

April 15, 2013

6:00 9:00 p.m.

Sponsoring Committees:

Commercial Law & Uniform State Laws

Janet M. Nadile, Chair

Professional Ethics

Jeremy R. Feinberg, Chair

Borrowing from Peter to Sue Paul:

Legal & Ethical Issues in Financing a

Commercial Lawsuit

Program Chair

James M. Haddad

Law Office of James M. Haddad

Faculty

Harvey R. Hirschfeld

Chairman of the

American Legal Finance Association

LawCash

Professor Anthony Sebok

Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law

Selvyn Seidel

Chairman & Principal

Fulbrook Capital Management LLC

Sandra Stern

Nordquist & Stern PLLC

Aviva O. Will

Managing Director

Burford Capital LLC

Borrowing from Peter to sue Paul:

Legal & Ethical Issues in Financing a Commercial Lawsuit

April 15, 2013

AGENDA

6:00 6:05 p.m. Introduction & Overview of Program

James M. Haddad

6:05 6:45 p.m. Legal Lending, Financing, Funding & Investing

Legal & Ethical Issues from the Funders Perspective

How it works, whats available, what it looks like, individual plaintiff vs.

divorce vs. class vs. commercial, etc., ethical concerns and constraints,

regulatory framework, privilege, confidentiality, conflicts, control,

involvement, funder liability, duty to know, duty to advise, lawsuits,

Spitzer agreement, proposed legislation, social policy, etc.

Harvey R. Hirschfeld, Selvyn Seidel & Aviva O. Will

6:45 6:50 p.m. Break

6:50 7:10 p.m. Funders Perspective (continued)

When to use various types of funding, how third party funding impacts

tactics and strategy, privilege, confidentiality & the lenders involvement

& liability

7:10 7:20 p.m. Panel Q&A

7:20 7:25 p.m. Break

7:25 8:00 p.m. Litigation Funding View from the Counsels Table

A view of the practical, tactical, ethical, legal, regulatory, legislative and

social issues from the viewpoint of the practitioner/professional/ethicist.

Professor Anthony Sebok

8:00 8:05 p.m. Break

8:05 8:15 p.m. Panel Discussion & Q&A

8:15 8:20 p.m. Break

8:20 8:50 p.m. Securing, Collecting & Alienating the Collateral

Sandra Stern

8:50 9:00 p.m. Final Q&A Session

Panel

This program will fulfill 3.0 CLE credits total: 1.0 skills & 2.0 ethics for the

MCLE requirement for NY, NJ & CA & 1.0 general credits & 1.75 ethics (pending) for Illinois &

1.0 general credits & 1.5 ethics for PA.

Borrowing from Peter to Sue Paul:

Legal & Ethical Issues in Financing a

Commercial Lawsuit

April 15, 2013

Table of Contents

Time to Pass the Baton? .......................................................................................................1

By: Selvyn Seidel

[Law School's] Duty to Know [and to Teach Third Party Funding] ...................................5

By: Selvyn Seidel

The above two articles are reprinted with permission from

www.CDR-News.com

The Lawyers Duty-to-Know & Duty-To- Tell in Third Party

Party Funding: A Time to Recognise & Respect these [Legal and Ethical] Obligations ....8

By: Selvyn Seidel

Investigating in Commercial Claims; New York Perspectives

NYSBA, New York Dispute Resolution Lawyer .............................................................11

By: Selvyn Seidel

Reprinted with permission from: New York Dispute Resolution Lawyer,

Spring 2011, Vol.4 No. 1, published by the New York State Bar Association,

One Elk Street, Albany, New York 12207

Investment Arbitration Claims Could be Traded like Derivatives .................................16

By: Rebecca Lowe

This article was first published for IBA Global Insight online news

analysis, 8 February, 2013. [available at www.ibanet.org] and is

reproduced by kind permission of the International Bar Association,

London, UK International Bar Association

Third Party Litigation Financing: A New York City Bar

Formal Ethics Opinion .......................................................................................................19

American Bar Association Commission on Ethics 20/20: White Paper

on Alternative Litigation Finance ......................................................................................20

Copyright 2011 by the American Bar Association.

Reprinted with permission.

The New, New Thing: A Study of the Emerging Market in Third-Party

Litigation Funding, November 2010..................................................................................61

Reprinted with permission of Fox Williams LLP.

Professional Responsibility and Third Party Litigation Funding A

Brief Tour of the ABA White Paper ..................................................................................84

By: Anthony J. Sebok

This report was prepared by Anthony Sebok. Reprinted with permission.

American Bar Association Commission on Ethics 20/20: Informational

Report to the House of Delegates ......................................................................................90

By: Anthony Sebok & W. Bradley Wendel

Copyright 2011 by the American Bar Association.

Reprinted with permission.

Litigation Finance: A Market Solution to a Procedural Problem ....................................130

By: Jonathan T. Molot

The above article was reprinted with permission from the author

Jonathan T. Molot and from Georgetown University Law Center

Georgetown Law Journal 2010

Stopping the Sale on Lawsuits: A Proposal to Regulate Third-Party

Investments in Litigation .................................................................................................181

Prepared for the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform by John H. Beisner

& Gary A. Rubin, Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP.

October 2012. All rights reserved.

Litigation Financing .........................................................................................................201

By: Sandra Stern

This section is adapted from Sandra Stern, Structuring and Drafting Commercial

Loan Agreements (copyright 2012 Thompson Media Group). Reprinted with

permission of the publisher and sole copyright owner. All rights reserved. Structuring

and Drafting Commercial Loan Agreements is available at a 10 percent discount

to program participants through June 30, 2013.

To receive the discount when ordering, please go to

http://www.sheshunoff.com/products/Strucutring-and-Drafting-Commerical-Loan-

Agreements.html and enter the code SCLA13.

Or you can contact customer service at 800.456.2340

Notes on the Faculty .................................................................................................................. i

Conference preview

46

THIRD-PARTY FINANCE: CONTROL

long smouldering

issue in the third-party

funding industry relates

to what might be called

the control doctrine.

Control in this

context has generally

been understood to

mean decision making authority, the basic

purport being that decision making must

remain with the claimant, with advice from

their lawyer. Te funder can consult and

advise, but only within that fenced-in area.

The control doctrine and its

current status as an inhibitor

Funders have always been challenged on the

ground that they, as third parties, should

be prohibited from taking over control of

anothers claim.

1

A key fash point has been

the decision regarding whether to settle a case.

Tis decision, which is central to any dispute,

can and does generate conficting interests

and positions between the claimant and the

funder. Te control doctrine says that this

decision remains with the claimant (on advice

of counsel) at all times.

A

TIME TO PASS THE

1

f

47

Commercial Dispute Resolution

NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2012

Selvyn Seidel of Fulbrook Capital

Management argues that the long held

control doctrine in third-party financing is

long past its sell-by date, and needs to be

replaced by a new set of guiding principles

for the industry to reach its full potential

www.cdr-news.com

In some jurisdictions such as the UK, the control doctrine also

means that the claim owner might be handicapped or prohibited

altogether from selling the claim in its entirety. In the US, sale of

the entire claim has been condemned in diferent circles such

as where patent claimants sell their claim to a third party to

prosecute it as that partys own. Te buyers in such instances are

ofen non-practicing entities (NPEs), more commonly known as

patent trolls.

For one who runs afoul of the control doctrine, the penalties

can be painful. Tey range from making the funding agreement

unenforceable to imposing sanctions on the funder, exposing

the funder to civil and ethical liability or perhaps even to

criminal sanctions.

Te purpose and policy behind these restrictions and

prohibitions are varied and not subject to convenient and

comprehensive summary. But they seem traceable to at least

several concerns. One is that a claim is personal to the holder, to

have and to hold until death do them part. Te two simply cannot

be delinked through commercial barter or otherwise.

According to some observers, it is also wrong to consider

parting the owner from the claim. Comparisons are sometimes

made with elderly peoples interests in life proceeds from

insurance policies, on grounds that here too the owner

should not be divorced from his or her right. Comparisons

are also made to sales of interests in patents.

Basic champerty concerns have underpinned the purpose

and policy pronouncements. Champerty has from its birth

in the Middle Ages refected concerns that a claimant is

generally in such a helpless position that it is vulnerable to a

third party purchaser taking advantage of it in the transfer.

Te champerty champions also fear that free trade in claims

enhances the possibility that litigation will itself be increased

intolerably by mercenaries.

Te doctrine of control has thus far been respected by

the industry. Actually, it might be said that the industry has

gone overboard in its deference to and fear of the doctrine.

For example, the common position of established members

of the funding industry is that once a case is funded, they

are hands of. Tat position refects champerty-fear at

work.

Despite the doctrines long history and serious challenges

to the funding industry, the doctrine itself is now not only

being challenged, it is in fact being diluted and discarded.

Why the control doctrine is on its way out

Critics of the control doctrine have, in strictly limited

numbers, just started to step up. Moreover, without fanfare,

the doctrine is in reality already gone or rapidly receding

2

Conference preview

48

THIRD-PARTY FINANCE: CONTROL

in important areas. For example, the transfer of control has been

allowed in part or in its entirety in a number of situations, including

when a mortgagee transfers its total interest to a third party (which

has already occurred in New York where the mortgagees have on

default of mortgagor sold the claims to another);

2

in bankruptcy

claims; and in certain European and Far Eastern jurisdictions. In

June, 2010, the New York City Bar Association issued an ethics

opinion on funding, indicating that control was acceptable. Consider

this alongside the contingency law relationship of lawyer to claimant

and claim, where the law in the US has carved an exception of

contingency lawyering from the champerty restrictions.

Further, at the urging of the bench, bar and government in

the UK, a group of funders issued a voluntary Code of Conduct

in November 2011. Despite the drafers expressed position that

restraints on control should in general exist, the Codes language

concerning control appears to leave some ambiguities that allow

for infuence, and more, on the part of the funders.

Te Code provides:

A Funder will . . . not seek to infuence the Litigants solicitor or

barrister to cede control or conduct of the dispute to the Funder. . .

(Clause 7 (c))

Within the four corners of this Code, can the funder accept

control if it does not seek control but the lawyer or barrister ofer it?

Beyond this, can the funder sidestep the lawyer altogether and go

directly to the claim owner itself and ask it to cede control, rather

than going to the lawyers?

Te Code might even be construed as creating an

accommodation for funders seeking infuence. It states

that where there is an irreconcilable diference of opinion between

the funder and the claimant, the parties can agree in their contract

to appoint an independent barrister to resolve the dispute fully and

fnally, and even though contrary to the wishes of the claim owner

(or the funder). Can this provision sustain an attack that it actually

crosses the line, giving the funder too much infuence? It is not too

far-fetched to raise this question when we see that some arguments

have already surfaced claiming that a funder who establishes

certain parameters agreed to at the beginning of the contract

with the claimant that assist in determining whether the case

should be settled, are themselves going too far in controlling a

settlement situation.

Furthermore, there is now a serious development in the industry

where some recently-established funders (including Fulbrook) are

acknowledging they are not hands of, but are hands on. Tey

assert that they are dedicated to supporting the claim afer funding,

from cradle to grave. Tey stop short of control, of course, but turn

the dial from hands of to hands on. Teir premise is that if

the claim is meritorious, then they can, by bringing their human

and capital resources to bear, enhance the value of the claim more

towards its true value.

The doctrine needs a push to finish it exit

Do not these developments and the current situation tell us that it

is time to revisit the doctrine and explicitly clarify, change, or even

discard it? Prior to now, it was probably politically premature to

raise this question too loudly (or at all). Te industry was too new,

struggling with too many issues, and trying to gain some traction

and credibility as a new development, to add a question about a

doctrine which had become so entrenched.

Now, with the industry gaining credibility and use, champerty

concerns fading in the commercial area, the doctrine itself causing

conspicuous problems, and with other developments in the industry

that cushion the removal of the doctrine, it seems to be a reasonable

time to ask this question.

In fact, the time is especially ripe in view of some developments in

the UK. For example, in the UK a law will come into efect in April

2013 which in efect allows lawyers to act as contingency lawyers.

Tis practice has been allowed in the US for a long time; it is

frequently compared to funding insofar as what third parties might

be allowed to do with regard to anothers claim, and it is treated as

an exception to the champerty rules. Tis major development in the

UK refects a mindset that comprehends third-party support of a

claim. Tat should bode well for the funding industry, and

the market.

It is also noteworthy that with the recent launch in the UK of the

Alternative Business Structures Act, third party business and fnance

parties can invest in law frms, and also be partners within such

frms. Among other things, and although there are restrictions on

amounts that can be invested and the degree of involvement of the

third party to make decisions in the lawsuit, this arrangement allows

third parties to put funds behind a claim, and to be involved in the

progress of the dispute. Te law frms can in turn commit capital to

various business ventures. Te Alternative Business Structures Act

is afrming, in one fashion or another, the concept of a third party

non-lawyers involving itself in a lawsuit, and indeed in a law frm.

Interested parties have been quietly and for some time

undermining and abolishing the control rules. A perfect example

can be drawn from the corporate world. Here, there is no doubt that

a third party can buy control of a company through, say, acquiring

30% with a stockholders agreement bestowing control over the

company. Tat control leaves complete control over any litigation

in the company. Te control is vested in a party who likely has little

idea what the litigation is about, let alone the best way to handle it. If

that is acceptable, what justifcation can there be to barring control

in a single case situation, particularly when the control in that case

should be far more informed and benefcial to a meritorious claim?

Similar questions can be asked about a private equity party which

buys a company, and is free to control it and its litigations. In a

forthcoming article, Professor Maya Steinitz, a leading expert on

funding, argues that funders are analogous to venture capitalists,

f

The original purpose of a limitation on a claimants transferring control over the claim protecting

the claimant as a self-appointed trustee is no longer alive because that claimant is not

helpless and in need of a guardian, but commercial

3

and that like such investors they should be

accorded the right to exercise substantial

control over a lawsuit.

3

In such a setting, is explicitly

acknowledging the right to control such a

revolutionary step? Mortgage, bankruptcy,

and patent cases already say the claim can

be transferred lock, stock and barrel, or that

a partial interest can be taken by a third

party. Contingency law supports the same

conclusion. Some courts both within and

outside the UK and US have already indicated

that this is possible. Te New York City Bar

association has indicated support

for a funders taking control under

circumstances that otherwise comply with

a lawyers ethical duties.

In this context it is worth noting that

the doctrine of champerty itself has been

debunked in the UK with legislation and

court decisions. It has, overall, fared

somewhat badly in the US as well, with at

least half the states abolishing the doctrine

altogether, and others restricting severely or

prohibiting its application when commercial

cases are involved.

4

As a result, champerty and maintenance

no longer can be used as they were to argue

that funding is by nature illegal and unethical.

Courts in the UK, the US and Australia leave

little doubt here.

Champertys marginalisation in the

commercial setting is well justifed. Te

original purpose of a limitation on a

claimants transferring control over the

claim protecting the claimant as a self-

appointed trustee is no longer alive because

that claimant is not helpless and in need of a

guardian, but commercial.

Indeed, it is the claimant that ofen wants

the option to transfer control, in return for

cash or other consideration. Te prohibition

is in fact a restraint on freedom of contract.

Moreover, it turns a deaf ear to the market. If

an informed market wants access to funding,

and thus to all the potential features of a

funding arrangement, who in the government

should be authorised to thwart that wish and

to deny access as a matter of public policy?

Second, since the predicate of a funded

case is its merit, the doctrine of champerty

serves no public policy purpose. True, the

courts may be overcrowded, but that is not a

reason to bar access by good claimants with

good claims. To the extent that there is a fear

that bad funders will support bad claims

and increase the frivolous population in the

courts, it should be addressed sufciently

by safeguards and rules already in the legal

system, and other rules that if needed can

be devised.

Tird, supporting good claims by

supporting good funding adds a fnancial

instrument and service to an economic

environment that needs them. Tese add to

both commercial and civil justice, and this

virtue is at the heart of the value of funding.

Exit a doctrine,

enter some new rules

It is thus submitted that no genuine

question should exist about whether the

control doctrine deserves to be buried. Te

only valid questions here are how related

rules and other protections that already exist

can be co-ordinated with this development,

and what new rules and protections might be

put in place. Tese questions can be illustrated

by asking how control enhances the funders

exposure to:

- liability for costs and fees if the claim loses

- sanctions along with the claimant, for

asserting a claim that turns out to be frivolous

- being treated as a full-fedged party for

various purposes, such as in determining

whether there is jurisdiction under an ICSID

Treaty, which requires or prohibits nationals

of certain countries, or someone subject to

discovery, or in determining the applicability or

non-applicability of the attorney-client privilege

or work product doctrines

- possible fduciary or other responsibilities,

such as from a controlling funder to a claimant

who is not in a control position, just as a

majority shareholder might have certain duties

imposed on it relating to the minority

W

ith the industry and market

active and growing, this

project cannot be put

on the back burner. All

stakeholders in the market, industry, and

among the defendant community, should

step up in this efort it afects each and

every interest.

Hopefully enough individuals will take an

ownership interest in the area and make an

efort to study the issues and help to enact

good rules that will protect the market, the

funders, and the defendants. Te time to start

this is today, not tomorrow.

www.cdr-news.com

49

Commercial Dispute Resolution

NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2012

About the author

Selvyn Seidel is the

founder, chairman and

CEO of Fulbrook Capital

Management LLC. He was

previously a co-founder and

chairman of the Burford

Group. Sandra Sherman

of Fulbrook assisted in the

production of this article.

1

See S. Seidel, Control, Commercial

Dispute Resolution Magazine,

September 2011.

2

S. Seidel, Investing in Commercial

Claims: New York Perspective, NYSBA

New York Dispute Resolution Lawyer,

Spring, 2011

3

Maya Steinitz, Te Litigation Finance

Contract, forthcoming, William &

Mary L. Rev. __ (2012), http://papers.

ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract-

id=2049528, comparing Funders to

Hedge Funds and Private Equity entities,

and indicating that these comparisons

support allowing greater infuence

by Funders coupled with greater

responsibilities.

4

See e.g., Anthony Sebok, Te

Inauthentic Claim, 64 Vanderbilt

Law Review 61, 30 January 2011,

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.

cfm?abstract_id=1593329.. http://

papers. Ssrn.com/sol3/papers.

cfm?abstract-id=1593329##

4

Third-party finance

xx

EDUCATING THE WORLDS FUTURE LAWYERS

or much of its life, third-party funding has

been an industry known to only a few, most

of whom were the funders themselves. Te

rest were essentially lawyers scattered here

and there. In fact, the industry was so young

that it somewhat embarrassingly struggled

to invent terminology defning its own

activities. Tis situation made third-party

funders vulnerable to those in more established quarters

who wished to challenge the industry, scare the market and

inspire regulators to action. Lack of public awareness and

understanding were for a long time public enemy number one.

Tis situation has however changed. Over time and afer

some heated debates and various studies the industry has

caught the eye and pen of the news media. It is also on the

agenda of conference planners who are launching ever-more

frequent events on the topic. Te market is learning, wants to

know more, and more parties are turning to funders to access

justice. Regulators are starting to sit up and take serious notice.

A growing number of insiders and interested observers alike

seem to have concluded that regulators should be involved

in some form or another. In the UK, for example, we see an

association of funders being formed to impose voluntary

rules and regulations. Additionally, in the US, we see Bar

organisations (the American Bar Association, the New York

City Bar Association, other state Bar associations) writing

reports and issuing guidelines, and some state legislators

starting to enact some legislation. Similar moves are afoot in

Australia, where the modern funding industry started more

than a generation ago.

Much however remains to be done. Tis articles position

is that while the overall process and these developments are

healthy, laudable and must continue, nobody should be resting

on their laurels just yet.

Lawyers duties and position

A critical part of this forward push is the drawing in of other

stakeholders. Lawyers have a robust duty here. With some

oor m

bbeen

of w

rrest

aand

that

to in

activ

fu fu fund nd nder ers vulnerable to t

who wished to challen

F

Lawyers need to start spreading the message about third-party finance options to the

clients, says Selvyn Seidel of Fulbrooke Capital Management. But in order to engender

this new awareness, the process has to start in the classroom at law schools

5

f

xx

Commercial Dispute Resolution

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2012

www.cdr-news.com

resistance and some expressed chagrin,

this author has written journal articles,

supposedly discovering, and then

emphasizing this discovery in conferences

and other presentations, a duty to know

and duty to tell on the part of lawyers

a duty to know about funding and to

adequately inform their clients so the

clients can choose whether to pursue

funding. Tis publication has been

among the frst to give due attention to

and regularly cover this feld. Indeed, in

a prior articles it has canvassed private

practitioners and others for their views,

and the results have revealed the truth and

beneft of this duty).

But sadly, most clients currently are not

adequately informed about funding or are

not informed at all. Linked with this is the

fatal fact that most lawyers are not yet able

to explain the concepts and pros and cons

in sufcient depth or in some cases at all.

Te lawyer however cannot decide

autonomously whether or not to inform

their clients, simply because they have

no choice in the matter. Tey must. Tey

have a legal and ethical duty to be aware

of third-party funding and to inform their

clients of its existence and purpose.

Tis is especially pivotal in a world

where lawyers potential vulnerability to

allegations of negligence is the topic of the

day. Continued tough economic times are

still afecting the legal market, with frms

downsizing, placing extra workloads on

those that remain and potentially teeing up

an environment for overworked lawyers to

get themselves into trouble.

The law schools duties

In order to help attack the knowledge

vacuum among private practitioners, law

schools must start seriously educating

their students about funding so that

when students qualify the concept will

be already familiar. It will have been a

learned tool and skill they can, from the

start, use to assist their clients to the extent

of their abilities. In addition, it will also

be knowledge that can protect them as

practicing professionals.

Without trying to be overly dramatic,

the need in this area is fundamental,

particularly given the development of the

industry and the markets growing appetite

for funding, as well as the responsibilities

and vulnerabilities, noted above, faced by

lawyers. While no scholarly study has yet

6

f

Third-party finance

xx

EDUCATING THE WORLDS FUTURE LAWYERS

been done here, it is safe to assume that no leading law school in

the world has a course on third-party funding. A brief although

not exhaustive survey of course oferings among the leading law

schools in the US, UK, Australia and Germany supports this.

Nor have we seen (although this is harder to detect) the use of

third-party funding taught as a module within a larger and more

comprehensive course, such as courses on law and fnance, or law

and business.

Tis is particularly worrisome and puzzling given the pace at

which third-party funding is developing. It is hardly profound

to say that the future demands made by the integration

of law, fnance and business with each other and with the

transformations going on inside each of these disciplines, mean

that law schools also need to keep up with todays evolutions to

provide students with an education that will be relevant to the

needs of tomorrow.

It might be noted that this need obviously applies beyond

third-party funding. Law schools in general have to become

more attuned to the current and future needs of their students.

Teaching what was good in the past does not do the trick.

Students need to become all-around practitioners, equipped to

understand and handle both issues and challenges, present and

future. Having a frm grasp of the nexus between law and fnance

as well as other areas of business and economics is essential.

Law Schools know this. Oxford Laws new joint degree

program of law and fnance, sponsored and run as a joint venture

between Oxford Law and the the Oxford Business School (Said

Business School), is perfect evidence of a willingness to move

with the times and lead the way into the future.

Te stakeholders of the legal education world are not oblivious

to the need to improve. In fact, the balance of evidence suggests

that they are, such as the recent 18-person study group assembled

by the American Bar Association to analyse over the next two

years the needs of the law school community to be more current

in its approach.

At the same time, we see reports coming out predicting an

increase of claims against lawyers as a result of challenging

economic conditions. Tis trend should be coupled with the fact

that law frms themselves are sufering from reduced profts and

diminished opportunities, a fact which can encourage lawyers

and law frms to travel a bridge too far in terms of their push for

greater efciency in client service and greater proftability, thus

enhancing their potential vulnerability to claims of malpractice

and other forms of misfeasance.

The takeaway

Law Schools everywhere need to open a new chapter perhaps

even write a new book. Just as lawyers have a duty to know and

a duty to tell, so do law schools or rather a duty to know and

a duty to teach. But semantics aside, the obligations are clear,

present and compelling.

Law schools can do a host of things to start this process. Tey

can, as suggested as an example by one of the leading US law

professors and experts in third-party funding, professor Maya

Steinitz of Iowa Law School, have teachers put together syllabi on

this topic to use as a module within another related course. On

the other hand, there is defnitely scope for full courses on the

topic, and lectures by lawyers or funders would be helpful. Online

courses might be another path for some. But these are just a

sample of what seem like manifold possibilities.

Te Bar should also be demanding more from law schools,

and the schools in turn should be demanding it from themselves.

Students, equipped with sufcient awareness, would be the most

vocal and important community of all. Once they start to learn

then their collective voice, as with young people in general,

should carry the day and point the way to the future.

About the author

Selvyn Seidel is the founder, chairman and

CEO of Fulbrook Capital Management LLC.

He was previously a co-founder and chairman

of Burford Capital. Clementine Travis, Bahar

Semani and Inge Mecke of Fulbrook Capital

Management all assisted with this article.

f

7

The Lawyers Duty-to-Know & Duty-to-

Tell in Third Party Funding: A Time to

Recognise & Respect these Obligations

Posted: 30th July 2012 08:53

By Selvyn Seidel

Introduction & Overview

A lively focal point in the Third Party Funding industry has been the obligations of the Funders. In the UK that

interest and related inquiries and analyses have resulted, after three years of study and debate, in the November

2011 launch of a UK Code of Funding about the Funders obligations. In the US, we have seen similar studies by

the American Bar Association and others, with publications of white papers and other reports relating to Funders

obligations.

It is now time that the obligations of others in the market and industry receive equal attention and helpful

guidelines. In this respect, the spotlight should fall, as a priority, on the legal and ethical obligations of the

lawyers for the claimants. In a recent media article, the question of lawyers obligations was raised with various

professionals, and those interviewed said that there should be obligations imposed on the lawyers. This article

was first published by Commercial Dispute Resolution, a leading journal on litigation, arbitration and funding, on

9

th

July 2012.

To kick off what hopefully will be a deep research dive into the area, this article contends that lawyers have what

should be called a Duty-to-Know, and Duty-to-Tell their clients about Third Party Funding. Only if the lawyer

has and fulfills these duties can their clients be given what they need to decide whether or not to seek Funding,

and if so, how? what kind? and from whom?

Ethical Duty

The duty seems to be both an ethical duty and a separate legal one. This is the case at least if one focuses on

the two most active litigation and funding jurisdictions in the world, the UK and the US. The ethical duty might be

found in various explicit and implicit rules in various jurisdictions. For example, in the UK, the newly modified (15

June 2011) Ethical Code of Conduct for Solicitors, the SRA Code of Conduct 2011, lays down this requirement.

Here, in the Code as well as the Indications of Behavior to the Code, there are any number of separate and

independent provisions that identify and generate these duties. Collectively, they say the same thing. (The prior

Code also contained a provision, RULE 9 that was often read to carry the same obligation).

Indeed the Code emphasises, as does this Article, the overriding importance that the public interest plays in this

situation (as in others). It reads:

Where two or more Principles come into conflict the one which takes precedence is the one which best serves

the public interest in the particular circumstances, especially the public interest in the proper administration of

justice. Compliance with the Principles is also subject to any overriding legal obligations.

8

The situation in the U.S. is similar. In general, lawyers of course owe clients a variety of ethical duties with

regard to Funding. This was discussed in an important and far reaching ethical opinion issued in June of 2010

by the Ethics Committee of the New York City Bar Association. (For example, the lawyer and the client may face

a conflict of interest when the lawyer is negotiating a financing agreement with the Funder.) Among the ethical

duties a US lawyer has, it would not be hard to spell out explicitly and/or by inference the Duty to Know about

third party funding and when appropriate, the Duty to Tell the client about it.

Legal Duty

Beyond ethics, a legal obligation can be taken from various possible legal sources. In the UK, an illustration of a

court decision supporting this position is the Queens Bench decision in 2010,Adris v. Royal Bank[2010] EWHC

941 (QB). There, the Court found that a solicitors failure to obtain costs insurance for his client, protecting

against adverse costs that later were incurred, was a gross breach of the Consumer Credit Act of 1974 s. 78.

Such a duty here, as in the area of Funding, is one that is rooted in the basic requirement that a lawyer be

competent in what the lawyer is doing, and provides his or her client with competent advice. The branches of this

fundamental requirement spread far and wide.

Specific Questions & Duties

Within the general duties posited, there is also a need to address concrete specific questions that abound. Can a

lawyer avoid culpability for lack of knowledge on the back of an argument that the industry is a young one

unknown to many or indeed most lawyers? Is actual knowledge the test, versus should have known? Is there

mandated knowledge, and automatic liability?

Does a duty apply in the UK not only to solicitors but also to barristers under the ethical and legal rules that apply

to barristers? Can an unknowing barrister maintain that knowledge and guidance here is the responsibility of the

solicitors only.

What do the duties entail? How much must be known? Must one know all the basic subtleties that go into

Funding? Should, for example, the lawyer be concerned about his or her potential lack of experience or capacity

to adequately understand and advise on the topic? What about an actual or potential conflict of interest?

Should independent advice be sought by the lawyer on behalf of the client?

What differences exist between common law systems as found in the U.S. and U.K., and civil law systems, as

found in Germany and France? What about nuanced differences within different legal systems? How are

conflicts resolved or harmonised?

In the study that should go into this area, there should of course be an opportunity for all stakeholders to voice

their views. The lawyers are of naturally at the head of the queue among that group. So also is anyone who has

challenged the industry on various grounds. The most vocal and well known one is the U.S. Chamber of

Commerce. It and any kindred spirit should have the chance to voice their views.

Conclusions & Recommendations

This article is of necessity short and summary, but that should not mask the scope of the need and

responsibilities to fill they are broad and deep. The market and industry are young. The guidelines are

relatively few, and a work in process. The emphasis to date has been on the requirements imposed on the

funders.

That emphasis on funders is producing results. However, alone, the results are inadequate. The market and

industry requirements weave a seamless web. The time has come to expand the emphasis to the other

stakeholders. The legal communitys duties are compelling, as ones instincts can confirm. Those duties should

be spelled out. The health of the market and industry need this. So does the legal community itself. The project

is not a small one. It requires collaboration of the different participants in the industry, clarifying the duties and

rights of each segment.

But most of all it takes leadership and time from the legal community. The Law Society in U.K., the bar

associations in the U.S. and elsewhere, are logical candidates to take this forward, as they have taken forward so

many other projects effecting the law and legal services. The industry should work hand in hand with these

groups.

In fact, the duties here go well beyond the practicing lawyers. Law schools and educational programs should be

informing their students about the industry and market, and how to act within them. A few are starting to do this.

But very few. At one point all the law schools should put this topic on their standard teaching programs.

In the meantime, regardless of the actual state of the ethical and legal responsibilities, it seems sensible to

assume there is a duty to adequately know, with a corresponding duty to tell. The assumption in practice will, in

9

the end, not only better serve the client, the market, and the industry. It will, in the end, better serve the lawyer.

It will also by itself provide impetus to the overall and more formal analysis of and reporting on the situation.

Selvyn Seidel is Founder and Chairman of Fulbrook Management LLC, and Co-Founder and former Chairman of

Burford. Clementine Travis, an associate at Fulbrook, contributed valuable assistance.

Selvyn Seidel can be contacted via email at sseidel@fulbrookmanagement.com

10

11

12

13

14

15

Investment arbitration claims could be

traded like derivatives

By Rebecca Lowe

Third-party funding of investment arbitration disputes is

rapidly growing into a lucrative financial market where cases

could ultimately be traded like derivatives, according to

insiders. And serious ethical concerns remain over the

growing power of an industry lacking both transparency and

regulation.

Funding bodies for both litigation and arbitration have

multiplied over recent years, but it is investment arbitration

funding that has provoked the most controversy. Proponents

say the funds improve access to justice and help keep costs down. Opponents argue they

encourage frivolous claims, create potential conflicts of interest and give funders

unwarranted control over public policy.

Selvyn Seidel, who co-founded Burford Group in 2009 one of the worlds biggest third-

party funders and has since founded Fulbrook Capital Management, describes the

change in the industry over the past two years as like night and day. I see it in front of

me, growing and growing, getting more credibility and spreading, he tells IBA Global

Insight. It is no longer an emerging industry, it is maturing, and in my view it will

inevitably reach maturity and be a good part of financial day-to-day life.

A commercial claim is no different from any other asset, Seidel explains, and can be

compared to a security or share. They can be bought, sold, financed, pledged. I think

they will eventually be part and parcel of derivatives. Some people say, isnt that a bad

thing? Well, they are good and bad. They can be good just like any other derivatives.

[Third-party funding] is no longer an emerging industry; it is

maturing, and in my view it will inevitably reach maturity and be a good

part of financial day-to-day life.

Selvyn Seidel

Co-founder, Burford Group; founder, Fulbrook Capital Management

Related links

x Have your say

x IBA Dispute

Resolution Section

x The impact of

third-party fundng

- DRI 6:1

16

Maya Steinitz, associate professor of law at the University of Iowa and a leading scholar

on third-party funding, believes the rise in interest in investment arbitration funding was

prompted by the global financial crisis. In forthcoming, unpublished research she draws a

parallel between investment arbitration funders and the so-called vulture funds that

grew up in the 1990s, which buy the debt of struggling nations at a discounted rate and

then claim for a higher rate than the creditor expected to receive.

There are certainly hedge funds and other entities that are paying close attention to see if

therell be the kinds of opportunities that the sovereign debt crisis in the 90s presented,

she says. The vulture funds that bought the arbitration awards against states [which gave

them control over the debt] are in a way what started this. Other investors thought, why

wait until there is an award? Why not get involved earlier?

Robert Volterra, co-founding partner of Volterra Fietta law firm and one of the worlds

top public international law specialists, is sceptical about the vulture fund argument. In

terms of third-party funders, I do not see the overlap with vulture funds, he says.

Apart from the fact that some NGOs do not like the fact that they are part of a process

that makes governments keep their promises and punishes them for stealing from foreign

investors without paying compensation.

Steinitz stresses that her research is in the early stages and she is yet to make a judgement

on the full ethical implication of investment arbitration funding. She is however clear that

it should be subjected to more rigorous scrutiny than the funding of commercial

arbitration due to the public policy issues at stake. Investment arbitration is waged

against governments, which means that it is ultimately the public who end up paying

when there is a loss. It is a different dynamic. Traditionally we have regarded states as

having sovereignty over deciding how to deal with public policy issues such as a

financial crisis. Now they have to deal with third-party funders who, unlike the original

claimant, never had a direct stake in the country.

The funder will have an influence over the case, but lawyers have to be

very, very careful in saying my duty is to the client, not to the funder,

There are very serious ethical issues that have to be looked at here.

Andrea Dahlberg

Arbitration practice manager, Allen & Overy

The US Chamber of Commerce has been one of the most vehement critics of third-party

litigation funding, arguing that it increases the volume of unmeritorious claims as funders

17

are willing to bet money on weak cases that have a chance of a large reward something

Seidel and other funders strongly deny. It also compromises the independence of lawyers,

the Chamber claims, by making them feel an obligation to funders rather than their

clients.

While the UK and US have voluntary regulation in place for third-party funding,

international investment arbitration remains unregulated. There are no requirements for

disclosure or the amount of control a funder can take over a case, and concerns remain

over potential conflicts of interest between arbitrators, counsel and funders.

Even lawyers who support arbitration funding in principle concede that such issues need

urgently to be resolved. The funder will have an influence over the case, but lawyers

have to be very, very careful in saying my duty is to the client, not to the funder, warns

Andrea Dahlberg, arbitration practice manager at Allen & Overy. There are very serious

ethical issues that have to be looked at here.

Seidel agrees that third-party funding should be disclosed. This would not only improve

transparency, he believes, but potentially speed up settlements and increase their value.

If its a respectable funder, it may give the defendant cause to think it is dealing with a

meritorious and credible claim, he says. So it may make it more likely to settle.

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

Released by the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform, October 2012

STOPPING THE SALE ON

LAWSUITS: A PROPOSAL

TO REGULATE THIRD-

PARTY INVESTMENTS

IN LITIGATION

181

Prepared for the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform by:

John H. Beisner and Gary A. Rubin

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP

All rights reserved. This publication, or part thereof, may not be reproduced in anyform without the written

permission of the U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform. Forward requests for permission to reprint to:

Reprint Permission Office, U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform, 1615 H Street, N.W., Washington, D.C.

20062-2000 (202-463-5724).

U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform, October 2012. All rights reserved.

182

Third-party investments in litigation

represent a clear and present danger to

the impartial and efcient administration

of civil justice in the United States. Such

third-party litigation nancing (TPLF)

occurs when a specialized investment

company provides money to a plaintiff

(or counsel) to nance the prosecution

of a complex tort or business dispute. In

exchange for this nancial assistance,

the plaintiff (or counsel) agrees to pay

the investor a portion of any proceeds

obtained through the litigation.

TPLF investments create the threat

of at least four negative public policy

consequences for the administration

of civil justice:

TPLF investments can be expected

to increase the volume of abusive

litigation. TPLF companies view

disputes as investments and they

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

can hedge any investment against

their entire portfolio of cases. This

makes them more willing to put

money into cases that are weak

on the merits but have at least a

chance of a large award.

TPLF undercuts plaintiff and lawyer

control over litigation because the

TPLF company, as an investor in the

plaintiffs lawsuit, presumably will seek

to protect its investment, and can

therefore be expected to try to exert

control over the plaintiffs and counsels

strategic decisions.

TPLF investments prolong litigation by

deterring plaintiffs from settling. The

TPLF investor is a third party that,

like the plaintiff and the plaintiffs

lawyer, demands a share of any

litigation proceeds. The plaintiffs

obligation to satisfy this extra demand

STOPPING THE SALE ON

LAWSUITS:

A PROPOSAL TO REGULATE

THIRD-PARTY INVESTMENTS

IN LITIGATION

183

2

makes reasonable settlement

offers less attractive.

TPLF investments compromise the

attorney-client relationship and diminish

the professional independence of

attorneys by injecting a third party

into disputes. Lawyers will inevitably

feel at least some obligation to the

TPLF investors, who are paying their

bills and who might be a source

of future business. As a result,

counsel may give less attention to

the clients interests, which should be

counsels sole concern.

Given the risks inherent in third-party

investments in litigation, the U.S. Chamber

Institute for Legal Reform (ILR)

supports establishing a robust oversight

regime to govern this type of TPLF at

the federal level. The risks of TPLF are

simply too acute to be left to industry self-

regulation. And since TPLF substantially

affects interstate commerce and the

federal courts, the federal government

has jurisdiction to oversee TPLF on a

uniform, nationwide basis.

The focus of a federal oversight regime

should be on TPLF investors. The lawyers

involved in TPLF-funded cases should

continue to be governed by state bar

associations and courts, and the states

respective rules of professional conduct.

ILR has engaged vigorously in recent

and ongoing debates about the impact

of TPLF investments on professional

conduct issues and will continue to do

so. But at this point, the most pressing

need is for investor oversight.

ILR favors legislation that appoints a federal

agency to regulate third-party investments

in litigation an agency empowered to

make rules and regulations in pursuit of its

mandate and to enforce any laws, rules, or

regulations governing TPLF. Substantively,

the federal oversight regime should include

legislative and rule-based safeguards against

the risks inherent in TPLF, including statutes

and court rules requiring the disclosure

of TPLF investments and requiring TPLF

investors to pay costs associated with

the litigation they generate (particularly

defendants discovery costs).

TPLF investments compromise

the attorney-client relationship

and diminish the professional

independence of attorneys by injecting

a third party into disputes.

184

3

has no other connection. In exchange,

the investor is promised a portion of any

recovery from the dispute. The nominal

borrower in these cases may be a

company involved in commercial litigation

or an individual or group of individuals.

In cases involving individuals or groups,

the plaintiffs law rm typically is heavily

involved in nding and securing the third-

party nancing and, in some instances,

is the real party in the TPLF relationship

that receives the funds.

In TPLF investment nancing, the investors

return is usually a portion of any recovery

that the plaintiff receives from the resolution

of the dispute, whether through litigation

or settlement. The amount of recovery the

TPLF provider will receive usually turns on

several factors, including the amount of

money advanced, the length of time until

recovery, the potential value of the case

and whether the case is resolved by trial

or settlement. In this type of TPLF, the

nancing entity essentially invests money in

the outcome of the plaintiffs case, betting

that it will be successful. TPLF nancing

arrangements generally are nonrecourse (in

whole or in part); the recipient of the funds

obtains money to pursue a proceeding and

is required to provide a return to the TPLF

company only if the recipient is awarded

damages at trial or settles on favorable

terms.

1

Third-party litigation nancing (TPLF)

describes the practice of a stranger

to a lawsuit providing money to a

party in connection with the lawsuit

for prot. TPLF generally falls into

two broad categories:

Consumer Lawsuit Lending, which

typically involves individual personal-

injury cases, and

Investment Financing, which

includes investments in large-

scale tort and commercial cases

and alternative dispute-resolution

proceedings.

In consumer lawsuit lending, a lawsuit

lending company advances money to

an individual plaintiff to cover living or

medical expenses essentially giving

him or her upfront cash while his

or her lawsuit is still pending. The

plaintiff agrees to repay the lender, with

interest, out of any proceeds from the

lawsuit. Interest rates on these loans

are commonly in the range of 3-5% per

month (which, even without compounding,

can mean 60% annually). These loans

are generally nonrecourse, which means

the plaintiff need not repay the loan if the

lawsuit is not successful.

In the investment nancing variant of

TPLF, which is the subject of this paper,

a specialized investment rm provides

nancing to plaintiffs or their attorneys for

litigation costs (including attorneys fees,

court costs, and expert-witness fees)

regarding litigation to which the investor

II. INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS TPLF?

185

4

As noted in the executive summary,

TPLF investments have at least four

negative consequences for the sound

administration of civil justice. Several

ILR publications, as well as commentary

by other authors, have explained these

consequences in more detail. Briey,

however, they are as follows:

First, TPLF can be expected to prompt

an increase in the ling of questionable

claims. TPLF companies are mere

investors and they base their funding

decisions on the present value of their

expected return, of which the likelihood of

success at trial is only one component. In

addition, TPLF providers can mitigate their

downside risk by spreading the risk of any

particular case over their entire portfolio

of cases and by spreading the risk among

their investors. For these reasons, TPLF

providers can be expected to have higher

risk appetites than most contingency-fee

attorneys and to be more willing to back

claims of questionable merit.

2

The most notorious example of this

problem was the investment by a fund

associated with Burford Capital Limited

in a lawsuit against Chevron led in an

Ecuadorian court alleging environmental

contamination in Lago Agrio, Ecuador.

Burford made a $4 million investment with

the plaintiffs lawyers in the Lago Agrio suit

in October/November 2010 in exchange

for a percentage of any award to the

plaintiffs. In February 2011, the Ecuadorian

trial court awarded the plaintiffs an $18

III. PROBLEMS POSED BY TPLF INVESTMENT

FINANCING

billion judgment against Chevron, which

is on appeal.

3

In March 2011, Judge Lewis

Kaplan of the Southern District of New York

issued an injunction against the plaintiffs

trying to collect on their judgment because

of what he called ample evidence of

fraud on the part of the plaintiffs lawyers.

4

Indeed, long before Burford had made

its investment in the case, Chevron had

conducted discovery into the conduct

of the plaintiffs lawyers under a federal

statute that authorizes district courts to

compel U.S.-based discovery in connection

with foreign proceedings, and at least four

U.S. courts throughout the country had

found that the Ecuadorian proceedings

were tainted by fraud.

5

According to a December 2011 press

release, as a result of [f]urther

developments, Burford conclude[d] that

no further nancing w[ould] be provided

in the Lago Agrio case.

6

Nevertheless,

its year-long involvement and its initial

decision to invest $4 million with the

plaintiffs lawyers despite allegations of

fraud in the proceedings powerfully

demonstrate that TPLF investors have

high risk appetites and are willing to back

claims of questionable merit.

Second, TPLF changes the traditional

way litigation-related decisions are made.

When no TPLF investment has been made,

the plaintiff, advised by counsel, decides

the legal strategy for pursuing the claims

asserted. TPLF can be expected to change

that dynamic. As an investor in the plaintiffs

186

5

lawsuit, the TPLF company presumably

will seek to protect its investment, and

can be expected to try to exert control

over the plaintiffs strategic decisions. The

plaintiffs lawyer, as the person being paid

by and possibly even retained by the

investor, may accede to those efforts.

Even when the TPLF providers efforts

to control a plaintiffs case are not overt,

the existence of TPLF funding naturally

subordinates the plaintiffs own interests

in the resolution of the litigation to the

interests of the TPLF investor.

Recent commercial arbitration between

a company called S&T Oil Equipment

& Machinery Ltd. and the Romanian

government provides an example. S&T had

sought nancing for its case from Juridica

Investments Limited, and, under their

agreement, Juridica paid some legal fees

for S&T in exchange for a percentage of

arbitration proceeds. After Juridica withdrew

funding, causing S&Ts case to collapse,

a sealed complaint led by S&T against

Juridica in Texas federal court alleged that

S&Ts own lawyers had begun seeking legal

advice from Juridica after Juridica began

paying their fees, and that Juridica required

the lawyers to share with Juridica their legal

strategy for the arbitration and any factual or

legal developments in the case.

7

The lawsuit-investment industry makes

no secret of its interest in protecting

litigation investments by inuencing cases.

A principal of investor BlackRobe Capital

Partners, LLC, was quoted as saying his

rm would take a pro-active role in

lawsuits.

8

A former Burford chairman said

that his new investment company would

not control litigation, but would do[]

more than was done before.

9

Third, TPLF prolongs litigation by deterring

settlement. A plaintiff who must pay a

TPLF investor out of the proceeds of any

recovery can be expected to reject what

may otherwise be a fair settlement offer,

hoping for a larger sum of money.

10

This

problem is illustrated by litigation between

a network-security company called Deep

Nines and a TPLF provider that had invested

in Deep Niness prior commercial litigation

against a software company. Deep Nines

had entered into an agreement with the

TPLF company to nance patent litigation

with an $8 million investment. Deep Nines

had a strong case, and eventually, the case

settled for $25 million. After paying off the

investor, as well as paying its attorneys and

court costs, how much did Deep Nines

actually keep? $800,000 about three

percent of the total recovery. The TPLF

investor took $10.1 million (the return of

its $8 million investment, plus 10% annual

interest, plus a $700,000 fee). Remarkably,

though, the investor wasnt satised

and sued Deep Nines in New York state

court for even more money.

11

More than

four years after the TPLF company rst

invested in Deep Niness suit, the parties

nally settled in May 2011. No settlement

terms were disclosed.

12

The Chevron/Lago Agrio case also

powerfully demonstrates this problem.

The investment agreement in that case

included a waterfall repayment provision,

which provided for a heightened percentage

recovery on the rst dollars of any award.

Under the agreement, Burford would receive

187

6

approximately 5.5% of any award, or about

$55 million, on any amount starting at $1

billion.

13

But, if the plaintiffs settled for less

than $1 billion, the investors percentage

would go up in fact, all the way down to a

mathematical oor of about $70 million, the

investor would get the same $55 million.

The effect of a waterfall is to maximize

the investors recovery early on, but it

incentivizes plaintiffs to continue litigating

in hopes of a higher settlement.

Fourth, TPLF investments compromise

the attorney-client relationship and diminish

the professional independence of attorneys

by inserting a new party into the litigation

equation whose sole interest is making a

prot on its investment. In recent litigation

regarding injuries to 9/11 Ground Zero

workers, for example, one of the plaintiffs

rms representing the workers was nanced

by a TPLF investment that provided for

passing the interest on the investment on to

the plaintiffs, to be paid out of any recovery

by them. After settling with the defendants,

the rm sought to pass along $6.1 million

in interest payments to the plaintiffs. The

plaintiffs lawyers argued strenuously

in support of their position. The judge

overseeing the settlement acknowledged

that passing on the interest to the plaintiffs

may be permissible, but disapproved doing

so in this case because it wasnt clear that

the plaintiffs had understood or approved the

charges.

14

Investor

5.5% of

any award

Plaintiffs

[I]f the plaintiffs

settled for less than $1

billion, the investor's

percentage would

go up...

188

7

for attorneys are not compromised, and

to continue to build awareness of the

dangers of TPLF and the need for reform.

While ILR addresses the ethical dangers

of TPLF with the ABA, it is simultaneously

addressing TPLFs other policy dangers

through public advocacy, including the

proposals contained in this paper.

B. Government Oversight

Is Necessary

ILR proposes to implement safeguards

against the dangers inherent in TPLF

through a regime of government oversight

and regulation. ILR believes that the

risks posed by TPLF investments are so

serious, and the incentives for misconduct