Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

0720 Nonprofit Rivlin0

Загружено:

Ra ElАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

0720 Nonprofit Rivlin0

Загружено:

Ra ElАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Keynote Address by Alice M.

Rivlin Director, Greater Washington Research at Brookings Non-Profit Survival of the Fittest: Crisis Management and the New Normal Co-hosted by the Center for Nonprofit Advancement, Leadership Greater Washington, and Orr Associates, Inc. July 20, 2010 Survival of the fittest doesnt have a real cheerful ring to it. I think everyone in this room knows that times are tough and are likely to stay that way for quite a while. My job is to try to give you some educated guesses about how economic developments might unfold, both at the national level and here in the Washington region, and how those developments might affect the non-profits that you are trying so hard to lead effectively. Gathered in this room are some of the people I admire mostpeople dedicated to making this corner of the world a better place to live and work; people who work extremely hard and dont get nearly as much credit as they should for it, people have seen their less empathetic former classmates making gazillions of dollars trading derivatives and wondered why the world is organized this waybut not wished they had chosen a different career path. I wish I could bring you major good news on the economic frontsomething to stand up and cheer about--but at the moment the best I can say is that I expect the national economy to improve over the next couple of years (and Washingtons with it), but quite slowly, especially with respect to jobs and unemployment. So your jobs are going to continue to be very hard. Outlook for the National Economy Collectively, we dug ourselves a huge hole and it will take a long time and a big effort to climb out. This is no ordinary recession. It is not a dip in business cycle that will right itself after a few months and let everyone get back to their normal activities. This recession was precipitated by a gigantic financial crash that brought credit to a screeching halt around the world in the fall of 2008, toppled venerable financial institutions, and is still far from over, despite out-sized efforts on the part of governments and central banks to prop up the system and control the damage. We know from centuries of experience

that recessions that result from financial crises are deeper than others and take much longer to recover from. And this crisis was a doozy! It not only started with a staggering financial meltdownthat could have been much worse if national authorities had not intervened so aggressivelybut the nature of the bubble that burst was particularly damaging. Bubbles happen periodically when people lose sight of reality and bid up prices of any assetstocks, land, art worksusually borrowing heavily to do so. They are sure they can pay back easily because the price will keep going up, so they ignore the risks. So prices do go up in a self-perpetuating cycleuntil they stop and the loans have to be paid back. But this burst bubble was particularly damaging because it did not involve stock prices or works of art this time. It was a housing price bubble with an enormous pyramid of bad mortgage debt, and derivatives of that debt, piled on top. Housing is a huge part of Americans household wealth. This burst bubble left us with more houses than we need, diminished household wealth, millions of foreclosures and mountains of underwater mortgages. It a really bad hole to be in. And we did it to ourselves. We didnt have to have this financial crisis. There were a lot of culprits: lax and cruelly predatory lenders, weak regulators, titans of finance that took out-sized risks with other peoples money and revealed not just their greed but their astonishing stupidity, and leaders whose ideological blindness kept them from noticing the perverse incentives that had crept into the financial system. It is important to remember how unnecessary this all was, so we make every effort not to let it happen again. We had not experienced a recession of this depth and pervasiveness since the 1930s, so it took a while for economists and others to recognize how bad it was. The catastrophe was occurring in the summer and fall of 2008, right at the climax of the national election. The economy was still deteriorating when the new team took over in January 2009 amid unrealistic expectations that a change of leadership could put things right in short order. Perhaps if there had been more time to absorb the depth of the economic fallas there was before Roosevelt came to power in 1933there would be less disappointment over the state of the economy now. If the polls are right, much of the public seems to have concluded that if the president and the congressional leadership havent fixed the economy after 18 months, they must be doing something wrong. It just couldnt be that hard! Unfortunately, I think it is that hard. Most of the policies, both fiscal and monetary, have been the right ones. They have kept the recession from getting worse and gotten us on the track to recovery. The stimulus put money in peoples pockets, sustained consumption, kept state and local governments from making even deeper cuts in services and laying off even more workers, and created and preserved millions of private sector jobs. There is plenty of evidence that without the stimulus unemployment would have been worse. The same could be said for the Federal Reserves policies of keeping interest rates low and supporting the mortgage and consumer credit markets.

But it could have been worse is not a winning slogan when unemployment is nearly 10 percent and people still live in fear of losing their jobs and homes. The free fall of spending has indeed turned around and GDP has been growing for over a year. But that spending growth itself has been moderate compared with past recessions when growth often spurted in recovery. Restrained spending is not hard to understand coming out of a recession that followed a frenzy of over-spending and over-borrowing, based partly on housing values that proved an illusion. The real mystery to economists is why more jobs have not been created by the sustained moderate growth in aggregate spending. By the rules of past recessions, we should have more jobs by now. But employers appear to have been producing more of whatever they sell with fewer workers (keeping productivity growth high), perhaps partly out of fear that the recovery wont last. This combination of slow spending growth and unusually low job creation relative to that spending is keeping unemployment distressingly high. Recent job numbers have been particularly disappointing and have led some to wonder if we are headed into another recessionthe proverbial double dipespecially now that the stimulus spending is coming to an end. It is hard to be sure, but I doubt it. My guess is that we will see continued slow growth and very gradual improvement in the unemployment rate, but no return to anything we could call full employment for several years. The situation is complicated by the government debt crisis in Greece and some other parts of Europe and fears of a debt tsunami in our own country. It is not news that the federal budget is on an unsustainable track for the next several decades. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid spending will rise faster than the economy can grow and faster than revenues. The combination of an aging population and rising health care spending produces a widening wedge between federal spending and revenues. People like me who worry about the federal budget have seen this coming for a long time. The projected debt trajectory is simply unsustainable. We cant borrow that much more every year without paying much higher interest rates and becoming increasingly vulnerable to a loss of confidence in our credit-worthiness. Before the financial crisis and the recession hit us, we had the illusion that there was time to fix the problem. Our economy was growing pretty strongly; our debt to GDP ratio was not very high. Sure, we faced a long run problem, but no imminent crisis. But the financial crisis and the recession forced us to borrow unprecedented sums very quickly-partly as a result of revenues falling off as they always do in recession and partly to respond to the recession and the financial meltdown. Hence, we find ourselves in very different situation from even two years ago. Debt to GDP has gone from under 40% to more than 60% and is headed rapidly up. The short-run deficits, which will recede as the economy recovers, will be overtaken by the longer run deficits caused by spending related to aging and health care out-running revenue. Quite suddenly we have a debt and deficit problem whose solution cannot be postponed much longer.

In 2010 we face a serious dilemma. We must not derail this fragile recovery. With unemployment still so high we need to extend unemployment benefits, help the states avoid drastic spending reductions, especially in Medicaid, and avoid pervasive tax increases. At this same time we must take real steps to bring down future deficits and reassure our creditors, here and abroad, that we have serious plans to rein in continuing future deficits. This is not a choice between stimulus and restraint. We have to do both at the same time: keep some stimulus going until recovery is assured and simultaneously take action that will reduce the rate of growth of future spending and add more revenues. We cant wait until economy recovers to design the deficit reduction; we have to start now. I am right in the middle of the deficit/debt dilemma because I am a member of the Presidents Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. We are a bipartisan group, co-chaired by Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, with eighteen members, twelve of whom are members of the Senate or the House. I am also co-chairing with my long-time friend, Pete Domenici, a Debt Reduction Task Force, sponsored by the Bipartisan Policy Center. Both are charged with presenting blue-prints for reining in future deficits and stabilizing the rising debt. Will we succeed? I am hopeful, mostly because I believe that more and more people (including many elected officials) realize that the status quo is unsustainable and inaction spells eventual disaster. But over-reacting and cutting deficits too soon could also derail the recovery and be very damaging. I was glad to hear this morning the Senate has acted to extend unemployment compensation. They should also do more to aid the states. Adding to the short-term deficit is not inconsistent with action to reduce deficits in the future. We have to be smart enough to keep two ideas in our heads at once. I have gone into the deficit issue because it is relevant to the economy non-profits will be dealing with in the futureafter the recession is over. We should not imagine that we can get through the recession and then go back to business as usual. Avoiding a future debt crisis will take heavy-duty budget action both on the spending and revenue sides. Federal spending cannot go on rising substantially faster than GDP forever. We have to slow down the growth of spending even if we increase revenues, because continuously raising revenues will eventually undermine economic growth. So we will see measures to reduce growth of Social Security and health care for seniors. We will also probably see restraints and probably freezes on discretionary spending programs. Federal grants will be squeezed and in turn the states will squeeze localities and service providers. This not a temporary situation, because the upward pressure on federal spending from the interaction of aging and health care inflation will not go away. We are facing a permanent squeeze on public spending. This means more responsibility will fall on the private and non-profit sectors. The Washington Area If we turn to the Washington area, the news is a little better, but only in the sense that this area has suffered far less than most other large metropolitan areas (metros). As we have seen, our Washington metro is not immune to recession and its consequences. In the last

two years unemployment is up, poverty has increased, and more people are turning to public and private agencies for relief from hunger and homelessness. Housing prices are down and foreclosures up. The drop in tax revenues has hit all local and state governments. All of this puts increased pressure on non-profits. To be sure, the recession has hit many other metros harder. The nature of our economy helps protect us. We have hardly any manufacturing and are not a leading financial center. We specialize in knowledge-based activity and services of all kinds, especially high-end business services. We have an unusually well-educated work force. The federal government is the engine that drives this economy, directly or indirectly, accounting for at least a third of economic activity. In response to economic crisis, not to mention two wars, federal activity is actually expanding. A national analysis of the 100 largest metros produced periodically by my colleagues at Brookings shows that all metros have been hurt by the recession, but some have suffered less than others and some are recovering quite strongly. We are one of the lucky ones. About a fifth of all large metros have made a full recovery in output (gross metropolitan product) and have had continuous output growth since the end of 2009. Washington is high on that list. The other favored metros are all state capitals or other centers of government or military activity. Employment, however, has not come back as fast anywhere, and Washington is no exception. Employment in the Washington area is still down about 2.2% from its peak, a relatively small drop in comparison to others. The drop in employment was 17% in Detroit, and Detroit was in bad shape even before the recession. Employment has begun to recover quite strongly in the Washington area, but is not back to its previous peak. However, one of the downsides of being a relatively well-off economy with strong future growth prospects is that we had a bigger housing bubble than most places and, when the bubble burst, a steeper decline and more foreclosures. We built a lot of new houses, especially high end houses, in the outer suburbs, many of which did not sell. We are beginning to work off this inventory of unsold houses, many of them bank-owned, but it will take time. Housing prices are still falling, although not as fast as they were. This is good news for buyers, many of whom took advantage of the temporary federal tax credit, but it is bad news for governments, which depend heavily on real estate taxes to finance services. Averages are misleading, especially in a region with such evident economic and racial/ethnic contrasts. Despite the obvious mixing of cultures and incomes in some parts of the region, the divide between east and west remains sharp. Poverty has risen in the less prosperous parts of the area, especially in the District, and child poverty is remarkably high. All of you can point to signs of hope and progress in schools, health care, housing, crime, and the environment. There is a new consciousness of the importance of green building, containing sprawl, and investing in healthy, walkable urban environments. But this good stuff that you are all engaged in will have to be done in a context of permanently

constrained resources. The combination of the likely slow recovery from the recession and the continuing pressure on public budgets resulting from demographics and rising cost of health care means that tough times are not going to end anytime soon. I believe this difficult economic prognosis has two major implications. First, we must learn to act regionally in deploying both public and private resources. Pollution and traffic congestion, for example, undermine the health and productivity of the region, but they cannot be solved by individual jurisdictions on their own. They are inherently crossborder problems that must be addressed with collective regional action. Second, nonprofits must work together to use their resources more effectively. In the words of a previous speaker, they must conserve, cooperate and consolidate to carry out their missions efficiently. If they do not, they will not be among the fit who survive.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Straw Man RevealedДокумент64 страницыThe Straw Man Revealedapi-1973110983% (60)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Estates and TrustsДокумент56 страницEstates and TrustsRa El100% (4)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Admiralty and Maritime LawДокумент252 страницыAdmiralty and Maritime Lawvran77100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Race Code ListДокумент38 страницRace Code ListRa El100% (1)

- Trusts-Ray StClair 2Документ91 страницаTrusts-Ray StClair 2Ra El100% (5)

- Womans WitchcraftДокумент88 страницWomans WitchcraftRa El50% (4)

- A Varactor Tuned Indoor Loop AntennaДокумент12 страницA Varactor Tuned Indoor Loop Antennabayman66Оценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Wapnick Kenneth A Course in MiraclesДокумент1 754 страницыWapnick Kenneth A Course in MiraclesCecilia PetrescuОценок пока нет

- How To Attain Success Through The Strength of The Vibration of NumbersДокумент95 страницHow To Attain Success Through The Strength of The Vibration of NumberszahkulОценок пока нет

- Manual Generador KohlerДокумент72 страницыManual Generador KohlerEdrazGonzalezОценок пока нет

- Henry Makow EssaysДокумент26 страницHenry Makow EssaysspectabearОценок пока нет

- LEASE BASIC RENTAL AGREEMENT or RESIDENTIAL LEASE This Rental Agreement or Residential Lease Shall Evidence the Complete Terms and Conditions Under Which the Parties Whose Signatures Appear Below Have AgreedДокумент4 страницыLEASE BASIC RENTAL AGREEMENT or RESIDENTIAL LEASE This Rental Agreement or Residential Lease Shall Evidence the Complete Terms and Conditions Under Which the Parties Whose Signatures Appear Below Have AgreedJaycee BernardoОценок пока нет

- LEASE BASIC RENTAL AGREEMENT or RESIDENTIAL LEASE This Rental Agreement or Residential Lease Shall Evidence the Complete Terms and Conditions Under Which the Parties Whose Signatures Appear Below Have AgreedДокумент4 страницыLEASE BASIC RENTAL AGREEMENT or RESIDENTIAL LEASE This Rental Agreement or Residential Lease Shall Evidence the Complete Terms and Conditions Under Which the Parties Whose Signatures Appear Below Have AgreedJaycee BernardoОценок пока нет

- Shakespeare Kabbalah and The OccultДокумент11 страницShakespeare Kabbalah and The Occultillumin7100% (2)

- Summary - A Short Course On Swing TradingДокумент2 страницыSummary - A Short Course On Swing TradingsumonОценок пока нет

- Pharmaceutical Microbiology NewsletterДокумент12 страницPharmaceutical Microbiology NewsletterTim SandleОценок пока нет

- Answer To 3 RD ComplaintДокумент2 страницыAnswer To 3 RD ComplaintRa ElОценок пока нет

- Tekla Structures ToturialsДокумент35 страницTekla Structures ToturialsvfmgОценок пока нет

- Attention:: Order Information Returns and Employer Returns OnlineДокумент6 страницAttention:: Order Information Returns and Employer Returns OnlineRa ElОценок пока нет

- Spa ClaimsДокумент1 страницаSpa ClaimsJosephine Berces100% (1)

- B 006D 1207fДокумент2 страницыB 006D 1207fRa ElОценок пока нет

- Certificate of Adoption Form 3927Документ1 страницаCertificate of Adoption Form 3927Ra ElОценок пока нет

- Alcohol Beverage Public InstructionsДокумент4 страницыAlcohol Beverage Public InstructionsRa ElОценок пока нет

- B 001 CN Cum - pdf6Документ8 страницB 001 CN Cum - pdf6Ra ElОценок пока нет

- Gace Program AdmissionДокумент109 страницGace Program AdmissionRa El100% (1)

- Demand LetterДокумент1 страницаDemand LetterRa ElОценок пока нет

- Answer and 3 RD ComplaintДокумент2 страницыAnswer and 3 RD ComplaintRa ElОценок пока нет

- Works of Ralph Waldo EmersonДокумент481 страницаWorks of Ralph Waldo EmersonRa ElОценок пока нет

- Teens and Technology 2013Документ19 страницTeens and Technology 2013aspentaskforceОценок пока нет

- AnswerДокумент2 страницыAnswerRa ElОценок пока нет

- The Tell El Amarna Tablets in The BritisДокумент406 страницThe Tell El Amarna Tablets in The BritisRa ElОценок пока нет

- Jury InstructДокумент3 страницыJury InstructRa ElОценок пока нет

- Aristotle S Treatise On RhetoricДокумент446 страницAristotle S Treatise On RhetoricRa ElОценок пока нет

- The Book of Adam and EveДокумент289 страницThe Book of Adam and EveRa ElОценок пока нет

- What About?: Questions Ordained Ministers Ask About TaxesДокумент4 страницыWhat About?: Questions Ordained Ministers Ask About TaxesRa ElОценок пока нет

- Georgia State University Graduation Report 03-16-10Документ11 страницGeorgia State University Graduation Report 03-16-10Ra ElОценок пока нет

- Basic Principles and GuidelinesДокумент9 страницBasic Principles and GuidelinesMike SerranoОценок пока нет

- MNO Manuale Centrifughe IngleseДокумент52 страницыMNO Manuale Centrifughe IngleseChrist Rodney MAKANAОценок пока нет

- MPPWD 2014 SOR CH 1 To 5 in ExcelДокумент66 страницMPPWD 2014 SOR CH 1 To 5 in ExcelElvis GrayОценок пока нет

- Hoja Tecnica Item 2 DRC-9-04X12-D-H-D UV BK LSZH - F904804Q6B PDFДокумент2 страницыHoja Tecnica Item 2 DRC-9-04X12-D-H-D UV BK LSZH - F904804Q6B PDFMarco Antonio Gutierrez PulchaОценок пока нет

- Land Use Paln in La Trinidad BenguetДокумент19 страницLand Use Paln in La Trinidad BenguetErin FontanillaОценок пока нет

- Database Management System and SQL CommandsДокумент3 страницыDatabase Management System and SQL Commandsdev guptaОценок пока нет

- Jainithesh - Docx CorrectedДокумент54 страницыJainithesh - Docx CorrectedBala MuruganОценок пока нет

- HW4 Fa17Документ4 страницыHW4 Fa17mikeiscool133Оценок пока нет

- Shares and Share CapitalДокумент50 страницShares and Share CapitalSteve Nteful100% (1)

- ACC403 Week 10 Assignment Rebecca MillerДокумент7 страницACC403 Week 10 Assignment Rebecca MillerRebecca Miller HorneОценок пока нет

- Catalog enДокумент292 страницыCatalog enSella KumarОценок пока нет

- GSMДокумент11 страницGSMLinduxОценок пока нет

- Vocabulary Practice Unit 8Документ4 страницыVocabulary Practice Unit 8José PizarroОценок пока нет

- T R I P T I C K E T: CTRL No: Date: Vehicle/s EquipmentДокумент1 страницаT R I P T I C K E T: CTRL No: Date: Vehicle/s EquipmentJapCon HRОценок пока нет

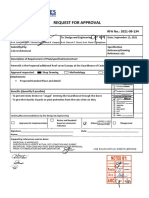

- CEC Proposed Additional Canopy at Guard House (RFA-2021!09!134) (Signed 23sep21)Документ3 страницыCEC Proposed Additional Canopy at Guard House (RFA-2021!09!134) (Signed 23sep21)MichaelОценок пока нет

- Perpetual InjunctionsДокумент28 страницPerpetual InjunctionsShubh MahalwarОценок пока нет

- ADS Chapter 303 Grants and Cooperative Agreements Non USДокумент81 страницаADS Chapter 303 Grants and Cooperative Agreements Non USMartin JcОценок пока нет

- A Study On Effective Training Programmes in Auto Mobile IndustryДокумент7 страницA Study On Effective Training Programmes in Auto Mobile IndustrySAURABH SINGHОценок пока нет

- BBCVДокумент6 страницBBCVSanthosh PgОценок пока нет

- Sun Hung Kai 2007Документ176 страницSun Hung Kai 2007Setianingsih SEОценок пока нет

- CNS Manual Vol III Version 2.0Документ54 страницыCNS Manual Vol III Version 2.0rono9796Оценок пока нет

- Si KaДокумент12 страницSi KanasmineОценок пока нет

- Consultancy Services For The Feasibility Study of A Second Runway at SSR International AirportДокумент6 страницConsultancy Services For The Feasibility Study of A Second Runway at SSR International AirportNitish RamdaworОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1.4Документ11 страницChapter 1.4Gie AndalОценок пока нет