Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Lettering and Type

Загружено:

gonzalolusiИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Lettering and Type

Загружено:

gonzalolusiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

lettering & TYPE

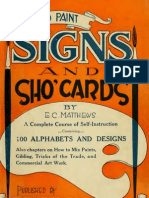

The works of commercial sign

painters often showcase inventive

and accomplished examples of

custom lettering in use.

creating letters and designing typefaces

Princeton Architectural Press, New York

bruce willen nolen strals

With A Foreword By Ellen Lupton

lettering & TYPE

Project Editor: Clare Jacobson

Copy Editor: Zipporah W. Collins

Designer: Post Typography

Additional Designers: Sara Frantzman and Eric Karnes

Primary Typefaces: Dolly and Auto, both designed by Underware

Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Bree Anne Apperley, Sara

Bader, Nicola Bednarek, Janet Behning, Becca Casbon, Carina Cha,

Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Carolyn Deuschle, Russell Fernandez, Pete

Fitzpatrick, Wendy Fuller, Jan Haux, Aileen Kwun, Nancy Eklund

Later, Linda Lee, Laurie Manfra, John Myers, Katharine Myers,

Lauren Nelson Packard, Dan Simon, Andrew Stepanian, Jennifer

Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton

Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657.

Visit our website at www.papress.com.

2009 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

Printed and bound in China

12 11 10 09 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without

written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of

copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Willen, Bruce, 1981-

Lettering & type : creating letters and designing typefaces / Bruce Willen

and Nolen Strals ; with a foreword by Ellen Lupton. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Design briefs)

Includes index.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-56898-765-1 (alk. paper)

1. Type and type-founding. 2. Lettering. 3. Graphic design (Typography)

I. Strals, Nolen, 1978- II. Title. III. Title: Lettering and type.

Z250.W598 2009

686.2'24dc22

2009003470

vi Foreword, Ellen Lupton

viii Preface

xi Acknowledgments

Context

1 Legibility, Context, and Creativity

6 A Compressed History

of the Roman Alphabet

Systems & Type-ologies

16 Systems

20 The Ideal versus the Practical

22 Conceptual Alphabets and Lettering

26 Writing, Lettering, or Type?

30 Letter Structure

33 Type and Lettering Classication

36 Exercise: Fictional Characters

38 Book Typefaces

42 Display Lettering and Type

Creating Letters

46 Thinking before Drawing

49 The Lettering Process

52 Foundations

54 Exercise: Flat-Tipped Pen

56 Creating Text Letters and Book Type

60 Modular Letters

63 Exercise: Modular Alphabet

64 Screen Fonts

66 Handwriting

68 Script Lettering

70 Casual Lettering

72 Distressed Type

74 Interview: Ken Barber

CONTENTS

Making Letters Work

Transforming Type

76 Customizing Type

78 Turning Type into Lettering

81 Exercise: Modifying Type

82 Ligatures and Joined Letterforms

84 Interview: Nancy Harris Rouemy

Lettering as Image

86 The Opaque Word

94 Interview: Shaun Flynn

Designing Typefaces

96 Behind a Face

99 Character Traits

100 Letterform Analysis

101 Lowercase

108 Uppercase

116 Numerals

117 Punctuation and Accents

118 Type Families

120 Spacing and Kerning

122 Setting Text

124 Interview: Christian Schwartz

126 Glossary

128 Bibliography

129 Index

4 1

2

3

vi

viii

xi

1

6

16

20

22

26

30

33

36

38

42

46

49

52

54

56

60

63

64

66

68

70

72

74

76

78

81

82

84

86

94

96

99

100

100

108

116

117

118

120

122

124

126

128

129

Letters are the throbbing heart of visual communication. For all the talk of the death

of print and the dominance of the image, written words remain the engine of infor-

mation exchange. Text is everywhere. It is a medium and a message. It is a noun and

a verb. As design becomes a more widespread and open-source practice, typography

has emerged as a powerful creative tool for writers, artists, makers, illustrators, and

activists as well as for graphic designers. Mastering the art of arranging letters in

space and time is essential knowledge for anyone who crafts communications for

page or screen.

This book goes beyond the basics of typographic arrangement (line length, line

spacing, column structure, page layout, etc.) to focus on the form and construction of

letters themselves. While typography uses standardized letterforms, the older arts of

lettering and handwriting consist of unique forms made with a variety of tools. Today,

the applications and potential of lettering and type are broader than ever before,

as designers create handmade letterforms, experimental alphabets, and sixteenth-

century typeface revivals with equal condence.

Type design is a hugely complex and specialized discipline. To do it well

demands deep immersion in the technical, legal, and economic standards of the type

business as well as formidable drawing skills and a rm grasp of history. This book

provides a friendly, openhearted introduction to this potentially intimidating eld,

offering a way into not only the vocabulary and techniques of font design but also the

sister arts of lettering, handwriting, calligraphy, and logo design. Simple, inventive

exercises expose readers to creative methods, inviting them to explore fresh ways to

understand, create, and combine forms. Throughout the book, the voices of some of

the worlds leading type and lettering artists illuminate the creative process.

Authors Bruce Willen and Nolen Strals are two of the sharpest young minds on

the contemporary design scene. I rst met them as my students at Maryland Institute

College of Art (mica), where they now teach courses in experimental typography and

lettering. Even as students, they were never march-in-line designers. Instead, they

were intellectuals with an iconoclastic edge who pursued their own view of art and

design, connected with music and cultural activism more than with the standard

professional discourse. Along with their maverick spirit, Bruce and Nolen have always

FOREWoRD

ellen lupton

brought an incisive and controlled intelligence to their work, which today ranges

from hand-screened, hand-lettered posters for the Baltimore music scene to sophis-

ticated graphics for the New York Times and the U.S. Green Building Council.

The initial concept and outline for this book were developed in collaboration

with MICAs Center for Design Thinking, which works with its students and faculty

to develop and disseminate design research. The books voice and philosophy reect

the authors unique point of view as artists and thinkers. Letters, they suggest,

are alive and kicking. Anyone who is fueled with a dose of desire and an ounce of

courage is invited to plunge in and take on twenty-six of the worlds most infamous

and inuential characters. The language of letters ranges from the bersophisti-

cation of fonts designed for books to the singular quirks of custom logotypes and

the clandestine mysteries of grafti. Its all there to be explored and grappled with.

Anyone who tries a hand at designing letters will walk away withat the very

leasta deepened respect for the opponent.

Saks Fifth Avenue

Valentine

Lettering, 2008

Marian Bantjes

Words communicate both visual

and written information. These

letters ornate ourishes eclipse

the words themselves to form a

larger image.

vii

Practical information about creating letters and type often amounts to a series of

truisms or guidelines for executing a particular process or style. While a designer

can apply every rule or typographic axiom literally, what makes lettering and type

design endlessly fascinating is the exibility to interpret and sometimes even break

these rules. Lettering & Type aims to present devotees and students of letters with the

background to implement critical lettering and type design principles, discarding

them when appropriate, and to offer readers a framework for understanding and

approaching their own worknot only the how but also the where, when, and

why of the alphabet.

Part of our own fascination with letters comes from the endlessly surprising

nature of these common objects. The ubiquity of letters in our daily lives makes them

a familiar subject matter, ready to be interpreted by generations of designers, artists,

and bored schoolchildren alike. Like many other designers, we have loved letters from

an early age, inventing our own comic book sound effects, illustrating our names in

our notebooks, and drawing rock band logos on our desks during math class. We have

yet to outgrow the enjoyment of losing ourselves inside a lettering or type project.

In a world governed by increasingly short deadlines, instant communications, and

machines that let us do more with less, spending an entire day drawing a handful of

letters is indeed a beautiful and luxurious act.

In Lettering & Type we have sought to create a book with a wide focus on

both the methods and the reasons for making letters, something that will appeal to

students of type design, ne artists, graphic designers, letterers, and anyone else with

a curiosity about the forms and functions of the alphabet. Our approach to Lettering

& Type comes from our experience teaching at the Maryland Institute College of Art,

as well as our own practice, which often extends into graphic design, illustration,

lettering, and type design. We have augmented our rsthand knowledge with the

inspiring work of contemporary designers and artists, and with lessons absorbed

from a wide range of theorists and historians.

Compliments of the B&O

Railroad Company

Dinner menu, 1884

Letters and design respond to

new ideas and technologies.

This illustration and its electric

lettering herald a newly

connected world, accessible by

the telegraph and railroad.

Library of Congress, Rare Book and

Special Collections Division.

PREFACE

Lettering & Type is organized into four sections, which build a broad, theoretical

overview of lettering, typography, and the roman alphabet into a many-bladed

reference tool for designing letters and typefaces.

Section One, Context, investigates the ideas and history that inform lettering

and typography, exploring the concepts of legibility, context, and creativity while

illuminating the alphabets complex evolution. This intellectual and historical

context sets the stage for Section Two, Systems & Type-ologies, which discusses the

systems underlying every typeface or lettering treatment and outlines a framework

for approaching, analyzing, and creating the attributes and elements of lettering and

type. Section Three, Creating Letters, dives deeper into the realities of constructing

letterforms, expanding the theoretical approach into a practical discussion of specic

methods and styles. Section Four, Making Letters Work, looks at letters as they are

appliedin situations from type design, logos, and lettering treatments to psyche-

delic posters and fantastic illustrative alphabetsproviding a practical and inclusive

foundation for designing typefaces and implementing lettering in the real world.

Accompanying the concepts discussed in the text, many contemporary and

historical examples of typefaces, graphic design, and lettering appear throughout

Lettering & Type. Supporting these illustrations are diagrams and exercises meant

to expand on specic ideas while dispensing lessons and advice that can be applied

to the readers own work. Interviews with skilled practitioners in the elds of type

design, lettering, ne art, and graphic design present contemporary perspectives and

approaches to designing and working with letters.

Envisioning, writing, and assembling all of these elements to create Lettering

& Type has been an enlightening and energizing process for us, as we have immersed

ourselves in the history and minutiae of lettering and type design. We hope that

readers will nd similar insight and inspiration within these pages, no matter what

their relationship is to the alphabet.

Opposite:

B vs RUCE

Drawing by the author, age ten.

Geometric Alphabet

Book cover (detail), 1930

William Addison Dwiggins

Parallel to similar explorations

in modern art and architecture,

lettering and type creations by

many early-twentieth-century

designers celebrated geometric

and mechanical shapes.

Lettering & Type would not have been possible without

the generosity of the design community and of this

volumes many contributors. We dedicate Lettering & Type

to everyone who has contributed artwork, wisdom, and

editorial suggestions, and those who have supported us

along the way. In particular we thank Ellen Lupton for her

condence in our abilities and her constant encouragement

and guidance in many of our creative endeavors. Her

extraordinary Thinking with Type was the inspiration and

exemplar for this volume and sets a high benchmark for

every typography treatise that follows it.

In addition we wish to the thank the following

people whose contributions, guidance, and assistance

have helped us realize Lettering & Type: Clare Jacobson at

Princeton Architectural Press and copy editor Zipporah

Collins, whose incisive guidance and editing have

brought this project to fruition; Ken Barber, Ryan Brown,

John Buchtel, Lincoln Cushing, Jennifer Daniel, Cara Di

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Edwardo, John Downer, Mike Essl, Shaun Flynn, Brendan

Fowler, Sara Frantzman, Laura Gencarella, Sara Gerrish, Isaac

Gertman, Sibylle Hagmann, Nancy Harris Roeumy, Kathryn

Hodson, Chris Jackson, Denis Kitchen, Tal Leming, Barry

McGee, Matt Portereld, Christian Schwartz, Underware,

Kyle Van Horn, Armin Vit, as well as all our other friends,

family, supporters, clients, and collaborators throughout

the years, including our former instructors and current

colleagues at the Maryland Institute College of Art and the

supportive MICA community at large, and especially our

studentswho have in turn educated usand whose work

graces these pages.

Most deeply of all we thank Sarah Templin and Sara

Tomko (for their enormous patience and tireless support),

Richard and Margaret Willen (for the invaluable advice

and editing), Katie Strals, Pete and Lou Strals, Chris Strals,

Mema, Papa, Grandma, all the Willens, Cohens, Needles, and

Moores, and all the Browns, Mumms, and Carlowes.

Main Drag

Installation, 2001

Margaret Kilgallen

Photo courtesy of Barry McGee

CONTEXT

Legibility, Context, and Creativity

Letters and the words that they form are homes for language and ideas. Like buildings,

letterforms reect the climate and the cultural environment for which they are

designed while adopting the personality of their content and designers. Although

letters are inherently functional, their appearance can evoke a surprisingly wide range

of emotions and associationseverything from formality and professionalism to

playfulness, sophistication, crudeness, and beyond. Designers and letterers balance

such contextual associations with the alphabets functional nature, melding the

concerns of legibility and context with their own creative voices.

As in all applied arts, functionality lies at the heart of lettering and typography.

Legibility is what makes letterforms recognizable and gives an alphabet letter the

ability and power to speak through its shape. Just as the distinction between a building

and a large outdoor sculpture is occasionally blurred, a written or printed character

can be only so far removed from its legible form before it becomes merely a conuence

of lines in space. Legible letters look like themselves and will not be mistaken for other

letters or shapesan A that no longer looks like an A ceases to function.

Letters or words whose visual form confuses or overwhelms the viewer disrupt

communication and diminish their own functionality. Such disruptions are generally

undesirable, but the acceptable level of legibility varies according to context. Some

letterers and designers pursue an idea or visual style rather than straightforward

utility. In these cases, the appearance of the letters themselves can take on as much

importance as the text they contain or even more. When used appropriately, less

legible letterforms ask the reader to spend time with their shapes and to become a

more active participant in the reading process. Unusual, illustrative, or otherwise

hard-to-read letters often convey a highly specic visual or intellectual tone and are

meant to be looked at rather than through.

Letter Box Kites

Alphabet, 2008

Andrew Byrom

The letters of the alphabet do

not always exist in two dimen-

sions. Letters can be structural,

functional, time-based, or even

interactive.

Unlike contemporary arts voracious quest for new forms, the impetus to

create unconventional or groundbreaking letters is generally less urgent to type

designers and letterers, whose subject matter is based on thousands of years of

historical precedent. As a letterform becomes more radical or unorthodox, it

begins to lose its legibility and usefulness, requiring designers to balance the new

with the familiar. This has not prevented letterers, artists, and designers from

creating an endless variety of novel and experimental alphabets. New forms and

experiments slowly widen the spectrum of legibility, shifting and expanding the

vocabulary of letters.

Two thousand years of reading and writing the roman alphabet have shaped

the standards of legibility and continue to sculpt it today. What was regarded as

a clear and beautiful writing style for a twelfth-century Gothic manuscript is to

todays readers as difcult to decipher as a tortuous grafti script. Nineteenth-

century typographers considered sans serif typefaces crude and hard to read,

yet these faces are ubiquitous and widely accepted in the twenty-rst century.

Familiarity and usage dene what readers consider legible.

The tastes and history that inform legibility are part of the context in which

letters live and work. Often hidden but always present, context comprises the what,

where, when, who, and how of lettering and type. At its most basic, context relates

to the ultimate use of any letter: What message will the letterforms communicate?

Where and when will they appear? How will they be reproduced? Who will view

them? But context also represents the broader cultural and social environment in

which letters function. Nothing is more important to an artist or designer than

context, because it provides the structure from which to learn and work.

Centuries of baggage have colored different styles of letters with a wide

array of associations, as contextual relationships are continually forged and

forgotten. When creating and using letterforms, designers harness, reinforce,

and invent these social and cultural associations. Long before the development of

movable type, the stately capital lettering styles of the Romans stood for power,

learning, and sophistication. As early as the ninth century, scholars, artists, and

politicians associated these qualities with Imperial Rome and sought to invoke

them by adopting Roman lettering styles. Even today, graphic designers employ

typefaces such as Trajan, based on Roman capitals, to convey an air of classical

Opposite top:

Les Yeux Sans Visage

T-shirt graphic and typeface,

2006

Wyeth Hansen

Hansens typeface, Didont,

pushes the high-contrast forms

of eighteenth-century modern

type to their natural extreme.

Despite the disappearance of

the letters thin strokes, the

characters underlying forms

can still be discerned.

Laptop for Sale

Photocopied yer, 2008

Rowen Frazer

This yer plays with context

through a tongue-in-cheek,

hand-drawn interpretation of

pixel lettering.

helvetica, 1957, Max Miedinger blur, 1992, Neville Brody

trace, 2008, COMA broadcloth, 2005, Post Typography

post-bitmap scripter helvetica, 2004, Jonathan Keller the clash, 2006, COMA

helvetica drawn from memory, 2006, Mike Essl signifcient, 2007, Jonathan Keller

These fonts all take the typeface Helvetica as their point of departure.

By redrawing, distorting, or digitally reprogramming its letterforms,

the designers reinterpret this ubiquitous font in new ways.

3 context

Practice and Preach

Poster, 2004

Ed Fella

The individuality of hand lettering can allow the artists drawing

style to act as a visual signature. Both of these posters are cohesive

despite their assortments of disparate letterforms.

Hotdogs and Rocket Fuel

Poster, 2007

Jonny Hannah

lettering & type 4

sophistication. Similarly, the crude stencil lettering painted on industrial and military

equipment now appears on T-shirts, advertisements, and posters where the designer

wishes to present a rough and rugged image. Even the most isolated or academically

constrained letterforms inevitably evoke cultural and historical associations.

Letters connotations and contextual relationships shift over time. Unexpected

usage of a specic style of type or lettering can create an entirely new set of associa-

tionspsychedelic artists of the 1960s co-opted nineteenth-century ornamental type

styles as a symbol of the counterculture. More routinely, the connotations of fonts

change through hundreds of small blows over the years. Type styles like Bodoni,

which were considered revolutionary and difcult to read when rst introduced, are

today used to imply elegance and traditionalism. Likewise, the degraded lettering

of the underground punk culture in the 1970s and 1980s is now associated with the

corporate marketing of soft drinks, sneakers, and skateboards.

While these contextual relationships often suggest a specic style or approach

to a lettering problem, the unlimited possibilities of lettering and type accommodate

numerous individual interpretations. Even subtle changes to the appearance of letters

can alter the contents voice. Designers sometimes add new perspectives or layers

of meaning by introducing an unexpected approach or contrast. Lettering a birth

announcement as if it were a horror movie poster might not seem entirely appro-

priate, but, depending on how seriously the new parents take themselves, it may

express the simultaneous joy and terror of birth and child rearing. The voice of the

designer or letterer, whether loud or soft, can add as much to a text as its content or

author. The designers ability to interpret context and address legibility underlies the

creative success and the ultimate soul of lettering and type.

Individual artists and designers inject creativity into the process of making

letters through their concept, approach, and personal style. Sometimes this individu-

ality takes a very visible form: an artists emblematic handwriting or lettering

technique acts as a unifying visual voice to words or letterforms. More frequently,

a particular idea or discovery informs creative type and lettering: a type designer

stumbles upon an especially well-matched system of shapes for a new typeface, or a

letterer adds a subtle-yet-decisive embellishment to a word.

Despite the countless numbers of letterforms that have been written, designed,

and printed, the possibilities of the roman alphabet have yet to be exhausted. The

skills, motives, and knowledge of letterers and type designers continue to inuence

the way that text is understood and perceived, placing the creation of letters within

both visual and intellectual spheres. The designers ability to balance and control

legibility, context, and creativity is the power to shape the written word.

5 context

A Compressed History of the Roman Alphabet

As tools and symbols that exist at the nexus of art, commerce, and ideas, letters

reect the same cultural forces that inform all other aspects of society. Institutions

and authorities from the Catholic Church to the Bauhaus to the Metropolitan

Transportation Authority have used their political and cultural clout to inuence,

manipulate, and establish the alphabets prevailing forms. Letters are not created in

a vacuum, and their appearance is as subject to the whims of power and taste as any

other feature of society. The roman alphabets history cannot be separated from the

history of Western civilization.

The shapes of the alphabet as we recognize them today became standardized

and codied in the fteenth century. Working during a period of commercial

expansion and technological innovation, Renaissance typographers took handwriting

and lettering styles and systematized them into movable type, a set of elements that

could be rearranged and reproduced. Type had already been in use for centuries in

China,

1

but the compact and efcient character set of the roman alphabet made

it especially adaptable to printing. This powerful combination would spread the

alphabet and literacy across the Western Hemisphere.

The roman alphabets phonetic nature makes it ideally suited to typog-

raphy. Where Chinese languages employ a logographic alphabet comprising tens of

thousands of distinct characters, the roman alphabet consists of twenty-six easy-to-

learn letters and their variants. Each letter corresponds to specic sounds of speech.

Though not perfectly phoneticsome phonemes are conveyed through combinations

like th, and many letters represent multiple soundsthe roman alphabet is a potent

system for transcribing written language. The ancient Greeks, whose own writing

system eventually cross-pollinated with the Romans, referred to the alphabet as

stoicheia (elements), in recognition of its powerful and fundamental nature.

2

Greece adapted its written alphabet from Phoenicias,

conforming Phoenician

characters to the Greek language. This early Greek writing system ltered through

the Etruscan civilization to the Romans, who rened and codied it to such a degree

that the Roman alphabet inuenced later evolutions of Greek. By the rst century

ad, the Roman uppercase was fully developed, and its forms are documented in the

formal inscriptions carved on edices throughout the Roman Empire. This ancient

Opposite:

Lindisfarne Gospels, Saint

Marks Gospel opening

Illuminated manuscript,

710721

Eadfrith, Bishop of

Lindisfarne

Insular medieval artists in the

British Isles departed from the

Roman forms of the alphabet,

creating inventive and highly

decorative letterforms such as

the INI that dominates this

incipit page.

The British Library Board.

All Rights Reserved. Cotton Nero D.

IV, f.95. British Library, London.

The letters of the roman alphabet have adopted many

forms and styles over several millennia. These are just

some of the common variants of the letter A.

1. Robert Bringhurst, The

Elements of Typographic

Style, version 2.5 (Point

Roberts, WA: Hartley and

Marks, 2002), 119.

2. Johanna Drucker, The

Alphabetic Labyrinth:

The Letters in History and

Imagination (New York:

Thames and Hudson, 1999).

lettering & type 6

300 B.C. 200 B.C. 100 B.C.

FORMAL GREEK ALPHABET

Classical Ionic/eastern alphabet adopted

and used in Athens.

ROMAN ALPHABET

Early formal lettering styles, as preserved

on Roman inscriptions.

greek

Roman alphabet is a direct ancestor of contemporary letterforms, and its composition

appears surprisingly similar to our own roman uppercase. The term capital letters even

derives from the location of inscriptions on Roman monuments, where this style of

letter is typically found.

Unlike the uppercase alphabet, which has clear origins, the roman lowercase

has a more convoluted background. The Romans considered their inscriptional,

uppercase alphabet a form and style distinct from their informal writing scripts

and cursives. Carefully built from multiple strokes of the chisel or brush, the stately

Roman capitals are lettering, as opposed to the handwriting used for books and legal

documents. Just as contemporary designers choose specic fonts for different situa-

tions, the Romans chose divergent styles and even different artisans for each unique

application. Contemporary roman uppercase comes from lettering, while the roman

lowercase forms are based on handwriting.

As Christianity became a dominant force in the Roman Empire, the church

deliberately began to distinguish its writing and lettering from the styles it associated

with Romes pagan past. Greekwhich was the churchs ofcial languageand its

lettering inuenced early Christian inscriptions, adding more freedom and looseness

to the Romans balanced alphabet. Emperor Constantine gave his blessing to a writing

style called uncial, which became the standard hand for many Christian texts. These

Greco-Christian inuences from within the empire collided with the writing styles

and runic forms of invading northern European tribes, who by the fth century had

overrun Rome several times.

The years after the fall of the Roman Empire were a turbulent time for Europe

and for the alphabet. Such periods of social, political, and technological upheaval

A Rough Timeline of the

Roman Alphabet

The alphabets evolution is not

linear. Divergent styles, schools,

and practices have coexisted

and overlapped throughout the

history of the roman alphabet.

This timeline loosely traces

the history of some styles and

movements that are key to the

evolution of the alphabet. Many

of these writing, lettering, and

typography styles correspond

with important historical

trends, reecting the external

forces that shape the alphabets

prevailing forms.

lettering & type 8

100 A.D. 200 300

OLD ROMAN CURSIVE

An early script used for informal writing.

ROMAN RUSTICS

Quicker, slightly less formal styles than Trajan letters

typically written with a pen or brush.

CLASSICAL ROMAN LETTERING

Formal Roman alphabet fully developed and in use, as exemplied

by the inscription on Trajans Column in Rome.

roman

often correspond with challenges and revisions to social and artistic standardsthe

Industrial Revolution, the years between the two world wars, and the development of

the personal computer all correspond to fertile and experimental periods in lettering

and typography. The early Middle Ages were no exception, as a wide variety of new

lettering styles and alphabets proliferated in Europe. Since the central authority and

inuence of Rome had dissolved, an increasing number of regional variations on the

alphabet developed around local inuences, Christian writing styles, and the angular

letterforms of northern Europe.

During this time, monks and scribes kept alive the basic structure of the

roman alphabet through the copying of manuscripts and books, including Greek,

Roman, and especially Christian texts. Some of these source manuscripts contained

ornamental initial capitals at the beginnings of pages or verses. As monks transcribed

the words of the gospels and manuscripts, they began, particularly in the British

Isles, to create extravagantly embellished initials and title pages whose lettering owed

little to the Roman tradition. These Insular artists treated letters abstractly, distorting

and outlining their forms to ll them with color, pattern, and imagery. Some of the

wildly inventive shapes are more decorative than legiblethese pages were meant

to be looked at more than read. The clergy, who already knew the gospel openings by

heart, and a predominantly illiterate society could view the exquisite lettering of these

incipit (opening) pages as visual manifestations of Gods word.

The wide variety of highly personalized, decorative, and irregular letters

that proliferated during these years reect Europes fractured and isolated political

environment. In 800 ad, Charlemagne briey reunited western Europe under

the banner of the Holy Roman Emperor. Consciously invoking Imperial Rome,

For more on the evolution of the

roman alphabet and typography,

see Nicolete Gray, A History

of Lettering (Oxford: Phaidon

Press, 1986); Johanna Drucker,

The Alphabetic Labyrinth

(New York: Thames and

Hudson, 1999); Gerrit Noordzij,

Letterletter (Point Roberts, WA:

Hartley and Marks, 2000); and

Harry Carter, A View of Early

Typography (London: Hyphen

Press, 2002).

9 context

500 600 700

HALF-UNCIALS

Alphabets with ascenders and descenders that use

both cursive and uncial forms.

INSULAR, MEROVINGIAN STYLES

New styles from the British Isles and

France that are less rooted in Roman

tradition.

CHRISTIAN STYLES

Looser compositions and lettering

inuenced by the Greek alphabet.

late roman & christian insular

UNCIALS

Formal book hands that synthesize elements of

Roman capitals, cursives, and rustics.

Charlemagne revived political and social practices of the Roman Empire, including

Roman lettering styles. His court letterers resurrected the forms of classical Roman

capitals, using the letters intellectual associations to give the Holy Roman Empire a

mantle of legitimacy.

The major alphabetic legacy of this Carolingian period is its minuscule writing

style. Distantly related to half-uncial scripts used by the Romans, the Carolingian

minuscule developed as a standard book hand meant to replace the fragmented

writing styles of western Europe. Carolingian minuscule is a clear, classical writing

style whose steady rhythm is punctuated by straight and decisive ascenders and

descenders. The minuscule would eventually evolve into the contemporary lowercase

alphabet, and todays readers can easily read and recognize most of its shapes.

Although the minuscule did not immediately catch on throughout the

continent, its impact was felt centuries later through the work of Renaissance writers

and artists. Italian humanist scholars and letterers moved away from the prevailing

gothic styles that had supplanted the Carolingian minuscule, turning once again to

ancient Rome and its classical letterforms. Their new, humanist writing style synthe-

sized minuscule and Romanesque gothic forms with the roundness, openness, and

regularity of classical Roman lettering. These lettera antica reect a renewed interest

in classical Roman and Greek art, literature, and design. It was this style that Italian

printers would translate into type later in the fteenth century.

While the rst European metal typefaces directly copied the pen-written

structure of gothic letters, some Italian typographers were beginning to distill

typographic letterforms from their handwritten cousins. Venetian printers such

as Nicolas Jenson (c. 14201480) and Aldus Manutius (c. 14501515) designed and

Gothic lettering, c. 1497

Giacomo Filippo Foresti

Sharp, pen-drawn gothic

lettering was used throughout

Europe in the late Middle Ages.

Writing and lettering styles

such as Rotunda, Bastarda,

Fraktur, and Textura (shown

here) were translated into

some of the earliest European

typefaces, and they remained in

use in some countries well after

the popularization of humanist

letterforms.

1000 1100 900

CAROLINGIAN STYLES

Along with Carolingian minuscule, a general

revival of classical Roman letter styles.

POST-CAROLINGIAN STYLES

Forms inuenced by, but starting to diverge from, Carolingian traditions.

ROMANESQUE

New, experimental forms showing

increased contrastprecursors to

gothic styles.

carolingian / holy roman empire romanesque

CAROLINGIAN MINUSCULE

A new alphabet partially based on half-uncial scriptthe

origins of todays lowercase alphabet.

commissioned some of the early and most inuential roman typefaces. Though

informed by lettera antica, these typographers did not merely imitate existing

writing. Instead, they regularized their letters into shapes that are more sculpted

than handwritten. This transformation from writing to type reected a classical and

rationalist approach, but, as signicantly, it emphasized the new tools and methods

used to produce type. Carving and ling away the shapes of metal typefaces brought a

new mechanization to letters that untethered type from the pen and set the stage for

developments that followed.

Fifteenth-century Venice was a center of Renaissance trade and printing, and

the widely admired designs of the Venetian printers roman type spread throughout

Europe. Looking beyond the handwritten form, European printers and typographers

continued to rationalize the alphabet. From the sixteenth through the eighteenth

century, type became progressively more structured and abstract. Type designers such

as William Caslon, Pierre Simon Fournier, and John Baskerville created typefaces that

moved farther away from the pen-written letter. Giambattista Bodoni, Firmin Didot,

and others developed intensely rationalist typefaces that owe more to mechanical

construction than to the uidity of handwriting. These transitional and modern

typefaces include few of early types ligatures and alternate glyphs, which were meant

to impersonate the motion and eccentricities of handwriting.

As typography became more rationalized, some letterers moved in the

opposite direction. By the sixteenth century, type had eliminated much of the need

for scribes and copyists. To distinguish their art from typography, master letterers

created writing manuals that taught intricate forms of cursive handwriting to an

expanding literate class. These writing and lettering styles exhibit Mannerist and

Ornate gothic capitals,

c. 1524

Giovanni Antonio Tagliente

The decorative ourishes

and geometric motifs of this

Mannerist calligraphy are

a prelude to the even more

amboyant lettering that

European writing masters

would create in the following

century.

11 context

1300 1400 1500

GOTHIC

Angular, compressed book hands that are

often paired with ornate, rounded capitals.

HUMANIST

A balanced writing style synthesizing Carolingian and

Romanesque hands with classical Roman forms and proportions.

RENAISSANCE TYPE

Movable type expressing Italian printers

classical and humanist design sensibilities.

ITALICS, MANNERISM

Script hands and type with more

exaggerated forms and axes.

renaissance gothic

Baroque tendenciesexaggerations in form and axisand their scripts incorporate

ornamental swashes and elaborate ourishes that cannot be mistaken for metal

type. Fraktur, the gothic counterpart to Mannerist and Baroque styles, mixes angular

pen-drawn forms with high-contrast, often extraneous embellishments. Created as

both lettering and type, Frakturs broken letters remained popular in the Germanic

countries long after roman styles became the norm elsewhere in Europe.

As the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

accelerated Western societys commercial aspect, it dramatically affected the forms

and uses of type and lettering. Signage for businesses and buildings took on a more

prominent role, and the demand for novel letterforms increased. During this period,

type designers began looking beyond traditional typography and classical writing to

the less-restrained work of lettering artists and sign painters. Certain gothic styles

were revived, and new, fanciful takes on decorative lettering found widespread use.

Making use of technologies such as wood type, foundries and designers exaggerated

and reinterpreted modern letters in outrageous and inventive ways, creating radically

bold fat faces, whose thick, ink-hungry strokes made them a prominent xture on

advertisements and other printed materials.

Fat faces and other imaginative new styles made the nineteenth century one

of type designs most fertile periods and laid the groundwork for contemporary

display lettering. Perhaps the most important development of this time was the

sans serif letter. While classical and isolated instances of sans serif lettering exist

throughout Western history (many Greek inscriptions lack obvious serifs) unserifed

forms had not caught on among letterers or type designers. A neoclassical revival of

Greek culture and architecture coincided with the insatiable desire for fresh styles

lettering & type 12

3. Nicolete Gray, A History of

Lettering (Oxford: Phaidon

Press, 1986), 173.

4. William Morris, Art and

Its Producers (republished

from the essay of the same

title, 1901, by the William

Morris Internet Archive, www.

marxists.org/archive/morris).

1700 1800

1900 2000

FRAKTUR

A gothic blackletter style used mainly in

northern European countries.

BAROQUE, ROCOCO

Letters in which the axis varies widely as type

moves farther from its origins; increasingly

embellished letters.

MODERN/NEOCLASSICAL

Rationalized letterforms with a vertical

axis and increased stroke contrast.

ADVERTISING TYPE

Bold, extreme, and experimental letters,

often ornamental or geometric.

ARTS AND CRAFTS

A revival of handcrafted forms inspired

by classical and medieval styles.

nineteenth-

centURY

neoclassical baroque

modern movements

ART NOUVEAU

Organic, uid, and expressive

letterforms.

DE STIJL

Elemental, geometric, and

grid-based letters.

BAUHAUS

MODERNISM

Geometric and

mechanical forms.

Rationalized, precise

forms, putting Bauhaus

ideals into practice.

PSYCHEDELIA,

POP REVIVALISM

Warped letterforms and

a revival of nineteenth-

century styles.

POSTMODERNISM

Deconstructed type and

digital experiments.

DADA

Lettering and type that celebrate

the chaotic and absurd.

and likely played a role in the invention of nineteenth-century sans serif

letters,

3

which began to appear in the work of sign painters and letterers.

New media and applications such as router-cut wood type and sculptural

signage were ideally suited to no-nonsense sans serif forms.

The unbridled commercialism and laissez-faire approach to

nineteenth-century letters inevitably provoked a backlash. Artists of the

Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, and similar movements returned in the

late 1800s to the artisan production values of the early Renaissance and

pre-printing era, emphasizing craft above commercialism. Calligraphers

and typographers like Edward Johnston (18721944) and William Morris

(18341896) dismissed the mass-produced, typically crude fat faces

in favor of humanist, often hand-drawn letterforms. Many of these

artists viewed their work in a communitarian lightWilliam Morris

saw handcraft as a tool to vanquish the great intangible machine

of commercial tyranny which oppresses the lives of all of us.

4

Such

renewed faith in the handmade caused letterers to gravitate toward a

more personal and organic alphabet, reviving both gothic and humanist

traditions. An increasing number of artists, architects, and other

A Lecture!

Broadside, 1853

In place of classical typographys reserved palette

of font styles, nineteenth-century printers

combined many outlandish, unrelated fonts. This

American poster mashes together novel styles such

as slab serifs, fat faces, and decorative typefaces.

Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections

Division.

nontraditional letterers began to move letterforms into a more abstract realm beyond

the conventional shapes of the roman alphabet.

The mechanized brutality of World War I effectively ended the Art Nouveau

movement and ushered in several new strains of lettering and typographic experi-

mentation. Dadaists and Futurists sought to destroy the meaning of language by

pushing the boundaries of legibility and readability. Modernist designers in the

de Stijl movement and at the Bauhaus experimented with scrupulously geometric

interpretations of the alphabet that removed all humanist traces from their letter-

forms. Melding the machine age with populist and socialist ideals, Bauhaus designers

attempted to create pure and mechanical forms of the alphabet, unencumbered by

historys baggage.

Like the renements applied to the roman alphabet in the late Renaissance, the

technological advances and experimentation of the avant-garde found a more rened

and practical voice in the mid-twentieth century. Typefaces like Helvetica and Univers

embody a modernized, postwar society pushing toward a more utopian outlook. It

is not too much of a stretch to say that the same forces of order and afuence that

midwifed the Roman uppercase and Renaissance typography informed midcentury

modernist type design.

Through the twentieth century and to the present, cycles of experimentation

and codication have grown progressively shorter. Midcentury modernism was

rejected by the psychedelic styles of the 1960s. Psychedelia was in turn co-opted

as pop typography and was followed in quick succession by postmodernism and

digital typography. The compression of typographic history is reected in contem-

porary lettering and type. The 1990s modernist revival, digital experimentation, and

a reinvigoration of handmade lettering have all taken place against the backdrop

of the internet, where the entire history of type and lettering rests at designers

ngertips. Myriad styles live side by side in an exponentially growing volume of

online content, while words and letters play an even more central role in day-to-day

life. Simultaneously, the knowledge and tools for conceiving lettering and type have

become more accessible, spreading to a more diverse section of the population.

Although the power to dene and dictate the standards of the alphabet is less concen-

trated, it is no less potent.

Typographic Collage

from Les mots en libert

futuristes

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti,

1919

Jan Tschicholds universal alphabet, designed in

1929, uses only straight lines and circles to build the

letters and phonetic marks of this single-case font.

Opposite:

Biennale de la Jeune

Creation

Fannette Mellier, 2006

Digital color calibration marks

become lettering on this art

exhibition poster.

15 context

systems &

type-ologies

Systems

Any lettering or type is based on a system. Like a moral code for the alphabet,

typographic systems are sets of visual rules and guidelines that govern the actions

and decisions involved in creating letters. These implicit systems enable characters to

work together, by regulating and dening their appearancedictating their shapes

and sizes, how they t together, and their visual spirit, as well as all other underlying

tenets of the letters. Lacking a strong code, a lettering treatment or typeface rarely

leads a successful life.

Analyzing and dening a typographic system is a bit like playing Twenty

Questions. Instead of Animal, vegetable, or mineral? one might ask, Serif, sans

serif, or mixed? Are the characters all the same width, or do they vary from letter to

letter? If there are serifs, what shapes do they take? Are the round characters at sided

or curved? Do the letters lock together, or are the spaces between them irregular?

The more questions one asks and answers, the better one can understand or create a

typographic system. A well-established system constitutes the core of any typeface.

Either consciously or unconsciously, type designers build and follow rules

that direct the myriad choices involved in creating a font. If a designer elects to draw

letters with very round curves, this decision affects every curved character in the

alphabet. If one or two letters do not reect the systems curves, they appear uncom-

fortable and out of place within the font. Even relatively minor choices like the size

of an is dot are telegraphed throughout the character set. Each decision that affects

an alphabets visual code or the way that any letters relate to each other is part of the

typographic system. By closely adhering to a system, a designer creates a typeface

whose characters interact in a natural and consistent way.

Matchstick Alphabet

(detail)

Alphabet, 2008

Lusine Sargsyan

Matchsticks radiate from

letter skeletons formed by the

bright red match tips, creating

an almost three-dimensional

effect. The unusual material

unites (and potentially ignites)

the eccentric characters of this

ammable alphabet.

Above:

Miss Universum

Typeface, 2005

Hjrta Smrta

Right:

Neon letters

Alphabet, 2008 (ongoing)

Hjrta Smrta

Like a ransom note, each of

these alphabets employs a

palette of mismatched letters,

building an unconventional

typographic system based on

the random and the unique

qualities of each character.

A shared physical material

rather than the forms of the

letters unies the recycled

neon sign alphabet.

lettering & type 18

Typographic systems do not always remain static. Only the most rigid idea-

driven systems of conceptual alphabets stay completely true to their origins. For

the typical lettering treatment, alphabet, or font, the designer constantly renes

and revisits the governing system as the project progresses. Sometimes a specic

character presents new challenges to the system, forcing the designer to revise the

parameters. New letters or words might suggest improved solutions to previously

drawn forms. Creating lettering and type is a lengthy process involving numerous

revisions to individual characters as well as to the typographic system.

As one-of-a-kind creations, lettering and handwriting accept more elastic

relationships between the characters, but systems govern them much as they do

typefaces. Unlike type, each lettered or written character is created for the specic

instance or word in which it is used, allowing the designer greater leeway to dene

the system. Since the letters themselves do not have to adapt to multiple situations,

their forms can be much more specic or unique. A lettering treatment may even

contain many versions of a single character that are visually united through the style

or personal hand of the letterer. Since the visual relationships between letters are the

engine of any lettering system, a consistent visual framework drives lettering just as

much as it does typesystems make letters work.

Freight Text

Typeface, 2005

Joshua Darden

Freights italic combines softly curved forms with angled, chiseled edges.

Sharp, wedge serifs are juxtaposed with rounded, ball-shaped terminals,

reinforcing the typefaces overall palette of round and faceted shapes.

Composite

Typeface, 2002

Bruce Willen

Distinctively shaped counters,

at-sided characters, and

selective use of slab serifs dene

the system of Composite. A

typographic system is developed

by applying these traits consis-

tently throughout the alphabet.

19 systems & type-ologies

bending the rules

Sometimes introducing

counterintuitive elements

into a typographic system

yields unexpected results.

While some other sans serifs

from the turn of the twentieth

century, such as Akzidenz

Grotesk, include a more

appropriate single-story

version of the letter, Franklin

Gothics anomalous g and the

fonts slightly exaggerated

stroke contrast give the

typeface added warmth and

individuality.

Futura: Preliminary Drawings and Final Lowercase Type

Drawings, 1925. Typeface, 1927

Paul Renner

Like similar experiments by other modernist designers, the letters of

Futura began with purely geometric circles and straight lines. The

nal typeface makes accommodations to legibility and typographic

tradition, adapting its geometric concept to the world of functional

typography. Futuras ne balance between the ideal and the

practical has sustained the typefaces popularity since its debut.

Even Futuras famously

geometric O is not perfectly

round. Slight adjustments

in stroke weight add proper

emphasis to the vertical sides

of the character.

Although Futura is based on geometric ideals, concessions such as

narrowing the width of letters and tapering strokes at connection

points improve the fonts legibility and overall functionality.

lettering & type 20

Romain du Roi

Engraved alphabet, 16921702

Louis Simonneau

The Ideal versus the Practical

Attempts to rationalize and standardize the alphabet are a recurring theme

throughout the history of lettering and typography. Countless artists, designers,

scientists, and even governments have developed model letterforms that embody

their philosophy or ideals of beauty and reect the social and technological context of

their eras.

Renaissance scholars and artists applied a newly analytical approach to

science, art, and the alphabet, drafting complex geometric templates to construct

idealized roman letters. As typography spread throughout Europe, these exercises

further deemphasized the handwritten origin of the alphabet, a trend that continued

through the following centuries.

In the 1690s at the behest of the French Acadmie des Sciences, a royal

committee began studying letter design, with the goal of developing an ofcial royal

alphabet. More than a decade later, the committee presented the resulting romain du

roi (kings roman) against a nely engraved grid (to which the letters did not always

conform). Robert Bringhurst designates the romain du roi as the rst neoclassical

typeface, because of its strict vertical axis, and the alphabets italic includes early

examples of sloped roman forms.

1

The romain du roi sought much of its inspiration in classical Roman letter-

formsconsidered the pinnacle of letter design by many artists and typographers

and idealized Roman lettering continued to inspire constructed alphabets from a

variety of sources. In the early twentieth century a new utopian model took hold, as

modernist experimenters reduced the alphabet to basic geometries of circles and

straight lines. Inuenced by the logic and efciency of modernism, designers such

as Jan Tschichold (19021974) and the Bauhauss Herbert Bayer (19001985) created

highly rationalized geometric letterforms. These alphabets were far removed from

the alphabets handwritten origins, as they imagined the letter reduced to its purest

mechanical forms.

Creating lettering or type is a tug-of-war between the ideal and the practical

the systems concept versus its functionality. The most successful typefaces and

lettering treatments nely balance the aspirations and constrictions of their concept

with the compromises, idiosyncrasies, and practicalities of application and legibility.

Renaissance designers of utopian alphabets discovered the limitations of applying an

inexible and uniform system to a fundamentally subjective and irrregular subject.

Likewise, the rigid geometries of the Bauhaus experiments found a more practical and

applicable voice in modernist typefaces such as Futura, Helvetica, and Univers, which

Underweysung Der

Messung

Constructed alphabet, 1525

Albrecht Drer

German artist Drer wrote

several treatises that

mathematically analyze

subjects as diverse as the human

form, perspective drawing,

and the alphabet. While

Drer managed to rationalize

many of the characters in this

gothic alphabet, when he was

confronted with less regular

forms, the idiosyncrasies of

handwriting crept into his

formula.

21 systems & type-ologies

1. Robert Bringhurst, The

Elements of Typographic Style,

version 2.5 (Point Roberts,

WA: Hartley and Marks,

2002), 129.

Perhaps an ultimate expression

of mechanically inspired

type, the forms of OCR and

MICR fonts (optical character

recognition and magnetic ink

character recognition) were

rst developed in the 1950s and

1960s specically to be read by

digital scanners.

successfully infuse the hand-derived forms of the roman alphabet with rationalized

qualities. Most type designers and letterers take this pragmatic approach, balancing

their ideal system with the requirements of legibility, utility, and context.

Conceptual Alphabets and Lettering

While the majority of fonts and lettering treatments accept the practicalities of

legibility, some designers refuse to compromise their original vision and system.

These conceptual letters or alphabets rarely aim to create the most readable text,

and their letterforms occasionally lack recognizably alphabetic characteristics.

Instead, conceptual alphabets illustrate or embody ideas, sets of constraints, and

editorial perspectives, illustrating their concepts through letterforms rather than

strictly pictorial means.

All type and lettering treatments begin with a concept, whether straight-

forward or elaborate. What sets conceptual letters apart is a rigid adherence to

their guiding principles above other concerns. Sometimes these alphabets tackle

complex subjects or associations, typographically translating an abstract idea,

opinion, or process. Other conceptual letters, such as the geometrically constructed

alphabets of the Renaissance, apply a rigid formula to their structure, forcing their

forms into the constraints of an inexible system. Like performance art, many

conceptual alphabets emphasize their creation process, with the end result being

less important than how they get there. A process-oriented alphabet may force

its designer to create letterforms under a very specic set of conditions or with a

particular, sometimes unusual, set of tools.

Unlike typical fonts or letters, some conceptual alphabets do not strive to

convey a particular lettering style or look, and the result may surprise even the

alphabets creator. Conceptual letters can take the form of a lettering treatment,

word, or poster created for a particular application. Others exist only in AZ form

and are never arranged into words. An increasing number of contemporary artists

and designers view the alphabet as a subject for art and experimentation, not just a

set of tools used to convey language. Conceptual letters are dedicated to their idea

above all else.

Opposite:

Having Guts

Lettering installations, 2003

Stefan Sagmeister with

Matthias Ernstberger, Miao

Wang, and Bela Borsodi

The words in this series of

constructed lettering treat-

ments appear and vanish as

the camera angle, lighting, or

arrangement of objects changes.

Photos by Bela Borsodi.

Fire in the Hole

Alphabet, 2006

Oliver Munday

Burned and disgured toy

soldiers summon a host of outside

associations to this alphabet.

lettering & type 22

lettering & type 24

Opposite:

Slitscan Type Generator

Adobe Illustrator script, 2006

Jonathan Keller

A custom computer script automatically generates this alphabet by

slicing and recombining the letters of every font on a users computer.

The script produces different results depending on the quantity and

styles of fonts that a particular user has installed.

Below:

Years of Love

Lettering installation, 2008

Hayley Grifn

Using birdseed as her medium, the designer

executed several lettering treatments in a

Baltimore park and photographed them over

three days.

Far right:

Conjoined Font

Typeface, 2006

Post Typography

Each character in this typeface connects to

others on a square grid, turning text into a

semi-abstract typographic pattern.

Right:

Imageability: Paths, Edges, Nodes,

Districts, Landmarks

Font family, 2002

Michael Stout

Based on Kevin Lynchs classic urban planning

book, Image of the City, this series of fonts

charts the forms of the alphabet through Lynchs

ve identiers for mapping and navigating the

urban environment.

Writing, Lettering, or Type?

Writing, lettering, and type represent three distinct methods of creating letters. A

written letter or word is created with very few strokes of the writing implement

think of cursive handwriting or a hastily scrawled note. Lettering builds the form of

each character from multiple, often numerous, strokes or actionsa love note metic-

ulously carved into a tree trunk or a hand-drawn letterform in grafti, for instance.

Type is a palette of ready-made shapes, enabling the reproduction of similar- or

identical-looking letters through a single actionlike summoning digital characters

from a keyboard or pressing a rubber stamp on a sheet of paper.

Writing emphasizes quick communication and execution above appearance.

Until the development of typography and, crucially, the spread of digital correspon-

dence, handwritings relative speed and ease made it the most reasonable method for

written communication. Imagine how long it would take to carefully draw each letter

of a grocery list, and the advantages of a legible and efcient writing system become

clear. This is not to suggest that writing is unconcerned with the aesthetics of letters.

On the contrary, many handwriting methods and primers throughout the centuries

have espoused the handwriting styles that their authors considered most beautiful or

legible. The ability to write well, in terms of aesthetics as well as articulateness, was

regarded as an integral part of literacy and education.

Lettered characters are constructed through multiple actions and may

involve several tools or processes. A digitally drawn logo, a neon sign, and a chiseled

inscription on a church doorway are all examples of lettering. Like writing, lettering

is a one-of-a-kind creation, designed for a specic application. Even master letterers

cannot duplicate exactly the same form from one instance to anothervariations

inevitably occur. Lettering differs from handwriting in that its main focus is usually

on technique and visual appearance. While speed may be important, it is generally

less so than the end product. More than it does in writing and type, context inuences

the way lettering looks. The uniqueness of each lettering treatment allows its designer

exibility and creativity to respond to a given context in very specic ways. Letters

can be compressed, warped, or interlocked to t a particular space. Words can be

built from the most appropriate medium or material, from pencil to stainless steel to

chocolate syrup.

This faded, hand-lettered

sign reveals the multiple

brushstrokes used to build each

character. Although it lacks

the dening characteristics

of type, careful lettering can

mimic typography.

27 systems & type-ologies

No War

Monumental lettering, 2003

Verena Gerlach

Designed to protest the war in Iraq, this lettering installation

uses a matrix of lit windows to form letters. The words

become legible as building occupants leave for the evening

and switch off (or leave on) the lights in each room.

Sketchbook pages

Calligraphy, 20062007

Letman (Job Wouters)

Some calligraphy blurs the line between handwriting and

lettering. As letterforms grow more polished and embellished,

they become more lettering-like. In some cases the artists

intent may be the only distinction between an expertly

written paragraph and a quickly lettered word.

lettering & type 28

Lettered or written characters that can be reproduced and rearranged become

type. Type unites the detail and formality of lettering with the speed and ease of

handwriting. The ability to create and reproduce preexisting characters through a

single action differentiates type from writing and lettering. Reproduction methods

have varied and evolved over the centuries. Metal and wood typefaces, rub-down

transfer letters, typewriters, rubber stamps, stencils, photo lettering, and digital

fonts are all examples of type. Types strength and beauty lie in its ability to look the

same in any context. One can type an A thousands of times and achieve a consistent

result, yet writing or lettering the same character will produce variations. Type also

constitutes a system of powerful relationships, which transform a palette of shapes

into a true kit of parts capable of endless recombinations. Like any set of tools, type

has power that is measured not just by individual elements but also by how the parts

work together. Unlike lettered and written characters, each typographic glyph must

be ready to redeploy into a new word formation at any time.

Thanks to digital technologies, typography has usurped many of writings

long-held roles. It is much faster and more practical to write letters, take notes, or

chart nances by typing on a computer than by handwriting these communications.

Likewise, graphic designers have replaced lettering artists with digital fonts that

can quickly reproduce effects similar, though not usually equal, to custom lettering.

The loss of personality and individuality found in handwriting and lettering is an

unfortunate side effect of the proliferation of type. Nonetheless, an exponentially

growing library of new and more sophisticated typefaces keeps increasing the range

of types voice.

Los Feliz

Typeface, 2002

Christian Schwartz with

Zuzana Licko and Rudy

VanderLans, Emigre.

Original sign lettering by

Cosmo Avila

Los Feliz is based on hand-

lettered signs on an auto parts

store in Los Angeles. The nal

typeface retains many of the

idiosyncrasies of the original

lettering, but standardizes

them into a more regular

system.

Photos by Matthew Tragesser.

Quick cursive and print hands

are two common forms of

writing. As characters become

more painstakingly executed

or constructed, they become

lettering. Type occasionally

mimics writing or lettering

styles with its ready-made

palette of shapes.

writing

lettering

type

29 systems & type-ologies

taper The thinning in or out of a

stroke, usually found at a join

cap height

x-height

baseline

ascender

descender

counter

serif

stem / vertical stroke

bowl

join The area where two strokes intersect

dot

apex

vertex

diagonal / diagonal stroke

leg

waist

spine

arm

tail

shoulder

eye

spur

nial

aperture

accent mark / diacritic

stroke A single mark and motion of the writing

implement; when applied to type or built-up

lettering, the term is more gurative

swash

connecting stroke

beak

punctuation

nial

tail

crossbar

crossbar /

horizontal stroke

terminal

descent

foot For more lettering and type

terms and denitions, see the

Glossary on pages 126127.

lettering & type 30

letter structure

reexive A serif that implies an abrupt

change in the direction of the

stroke, such as that found at the

feet of most roman letters

A serif that suggests a

continuous motion into or

out of a stroke, such as on

most italics

bilateral serif unilateral serif

unbracketed / abrupt serif bracketed / adnate serif

transitive

calligraphic serif,

asymmetrical

bracketed

serif

cupped serif

wedge serif unbracketed

serif

slab serif

clarendon

(bracketed slab)

latin

tuscan

antique tuscan

teardrop

terminal

ball terminal,

bracketed

ball terminal,

unbracketed

sheared

terminal

beak

text serifs

display serifs and nineteenth-century styles

terminals

serifs and terminals

represent the entrance and exit

marks of the pen. The origins

of various serif shapes relate to

different writing styles, tools, pen

angles, and amounts of pressure.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries, the forms of serifs and

terminals had become detached from

their calligraphic origins, as type

designers and sign painters treated

serifs as separate ornamental or

geometric elements.

31 systems & type-ologies

axis refers to the angle of emphasis

within a letter or stroke. Letters or

typefaces with modulated strokes

have areas of thicks and thins,

visible in rounded characters like

the o or a. Typefaces derived from

broad-nibbed pen writing typically

have a diagonal axis that reects the

angle of the pens tip. Multiple axes

can exist within the same font or

letter. Axis differs from slope, which

refers to the angle or slant of an

italic or oblique font.

(See also Angle of Translation

on page 52.)

contrast is the amount of

variation from thick to thin

within and between the strokes of

a character. Without any contrast

or stroke modulation, letters

suffer from uneven color, and their

horizontal strokes appear optically

thicker than their stems.

The x-height is the vertical

measurement of a lowercase letters

main body, usually dened by

the x. It differs from typeface to

typeface. Increasing a fonts x-height

increases the apparent size of the

letters and generally improves

legibility at small sizes. An exces-

sively large x-height can have the

opposite effect, reducing the overall

readability of word shapes and

making the letters seem graceless.

An x-height that is too small can

produce letters that look top-heavy

or stunted.

Rounded characters and pointed serifs extend slightly

above the cap height or x-height and dip just below the

baseline. These subtle overshoots optically compensate

for the softness or pointedness of the formswithout

an overshoot these characters would appear smaller

than the at or squared letters.

Ascenders may

be taller than

the cap height.

The x-height is

generally greater

than half of the

cap height.

lettering & type 32

adobe garamond adobe jenson dolly

baskerville didot futura helvetica

scala sans

low contrast

scala

medium contrast

Letters drawn with no

stroke contrast

didot

high contrast

Type and Lettering Classification

Like scientic classication, the categorization of letters and type enables one to

better analyze and understand their traits, forms, and history. Printers and type

historians rst devised classication systems in the nineteenth century, providing

order and categorization to an exploding menu of new type styles. The categories

generally correspond to periods of art and intellectual history, from the humanist

faces rst used during the Renaissance to the transitional fonts of the neoclassical

period. Different type foundries and scholars gave their own labels to letter classes,

and the specic names and descriptions continue to generate disagreement today.

Sans serif letters alone have been referred to as grotesks, grotesques, gothics, dorics,

antiques, and lineals. The actual terms of classication, however, are less important

than the characteristics and systems that they represent. One does not have to know

the scientic term for a dog to know that it barks.

At their most useful, categories of lettering and type represent sets of

attributes shared by many typefaces and lettering treatments. These classes give

designers and typographers a solid starting point for discussing and analyzing

typographic systems. Type categories are guideposts only, since their borders are not

absolute. While most letter examples can t into a single category, many defy neat

classication. Just because the attributes of scripts and slab serifs seem incom-

patible does not mean that slab serif script letters do not exist. Some transitional

or geometric sans serifs exhibit humanist inuences, while semi serif or mixed

serif fonts live with one foot in the serif and the other in the sans serif world. As

experimentation continues, letterers and type designers are not constrained by the

boundaries of traditional type categories.

33 systems & type-ologies

Humanist / Old Style

Renaissance- and Baroque-era type designers looked to Roman lettering and calligraphy as

inspiration for their typefaces. These humanist letterforms incorporate elements of calligraphic

handwriting such as the diagonal axis of the broad-nibbed pen and the softened, wedge serifs that

replicate the pen strokes starting point. Type designers continue to create contemporary revivals

and interpretations of humanist forms.

Transitional / Neoclassical

Transitional serif letters retain humanist traces, yet their forms are more ordered and rationalized

than old style characters. These rationalized features usually include a vertical axis, increased stroke