Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

1 Neck & Greene JSBM

Загружено:

dmaizulАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1 Neck & Greene JSBM

Загружено:

dmaizulАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Small Business Management 2011 49(1), pp.

5570

Entrepreneurship Education: Known Worlds and New Frontiers

jsbm_314 55..70

by Heidi M. Neck and Patricia G. Greene

We explore three worlds that entrepreneurship educators generally teach in and introduce a new frontier where we discuss teaching entrepreneurship as a method. The method is a way of thinking and acting, built on a set of assumptions using a portfolio of techniques to create. It goes beyond understanding, knowing, and talking and requires using, applying, and acting. At the core of the method is the ability for students to practice entrepreneurship and we introduce a portfolio of practice-based pedagogies. These include starting businesses as coursework, serious games and simulations, design-based thinking, and reective practice.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is complex, chaotic, and lacks any notion of linearity. As educators, we have the responsibility to develop the discovery, reasoning, and implementation skills of our students so they may excel in highly uncertain environments. These skills enhance the likelihood that our students will identify and capture the right opportunity at the right time for the right reason. However, this is a signicant responsibility and challenge. The current approaches to entrepreneurship education are based on a world of yesterdaya world where precedent was the foundation for future

action, where history often did predict the future. Yet, entrepreneurship is about creating new opportunities and executing in uncertain and even currently unknowable environments. Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship education have more relevance today than ever before. For many years, it was popular to ask, Can entrepreneurship be taught? As educators, we always said, yes, of course and went on to list the myriad of reasons rehearsed in advance of such questions. Our answers might include, it is a skill set, or we have been doing it for years, or it depends what you mean by entrepreneurship. In reality and

Heidi M. Neck is an associate professor and the Jeffry A. Timmons professor of entrepreneurial studies at Babson College. Patricia G. Greene is Presidents Distinguished Professor in Entrepreneurship at Babson College Address correspondence to: Heidi M. Neck, Babson College, Babson College, 231 Forest Street, Babson Park, MA 02457-0310. E-mail: hneck@babson.edu.

NECK AND GREENE

55

upon reection in looking at the future of entrepreneurship education, we may be willing to admit that we were wrong and willing to consider alternative explanations. Might it be that entrepreneurship, using current popular approaches, cannot really be taught and that realworld experience actually does supersede an expensive college education? Just look at Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Richard Branson, Mary Kay Ash, and Debbie Fields who are all incredibly successful entrepreneurs without a college degree. Should their success signal anything to entrepreneurship educators? Not really. For every Bill Gates, there are a million entrepreneurs who experience in the real world dramatic, life-altering failure that we do not read about in the popular press. We know what you are thinking. First, we say entrepreneurship cannot be taught. Then we suggest that experience supersedes education. Finally, we say ignore Bill, Steve, Richard, Mary Kay, and Debbiethe kings and queens of learning entrepreneurship outside the ivory tower of the academy. Confused? Our confusion is intentional to illustrate where we are as educators in the dynamic, cross-disciplinary eld of entrepreneurship. The academic eld and practical eld of entrepreneurship have consistently been at odds throughout the years, but such conict has led to a rich and diverse pool of collaborative educatorsacademics, entrepreneurs, consultants, investors, full-time, parttime, academically qualied, and professionally qualiedwith a common understanding that entrepreneurship education is important. Across the eld, there are differences in how we approach teaching entrepreneurship. Given the multidisciplinary eld of entrepreneurship, the content covered in most entrepreneurship courses is farreaching. An entrepreneurship educator is often expected to know everything about every eld. It is not uncommon to

teach aspects of strategy, nance, law, human resources, leadership, marketing, accounting, operations, and ethics in any given class. The next class might offer perspectives from sociology, anthropology, and business history. This is at a time when those in the discipline of entrepreneurship also strive for increased legitimacy as an academic eld, pushing for the research rigor that some suggest drives intellectual maturity (Brush et al. 2003). As a eld, entrepreneurship essentially covers prestart-up and beyond, from intellectual property to initial public offering. Though the eld of entrepreneurship has progressed beyond evaluating and describing the entrepreneur as the lone maverick with superhero powers, the entrepreneur is nonetheless a central gure in the emerging stages of business creation. As such, entrepreneurship educators also teach foundation principles, often considered the soft stuff, of living with uncertainty, opportunity identication, entrepreneurial mindset, creating, decision-making, developing empathy, business design, culture, lifework balance, social responsibility, and leveraging failure. The marriage of all of these content areas is value creation and capture entrepreneurship as an engine to create economic, social, and personal value. For many students of entrepreneurship, whereas their peers are pursuing careers, they are pursuing a life path. It looks different, it feels different; it is differentespecially in todays global environment. The purpose of this paper is to present a framework for teaching in a new world. We advance the concept of teaching entrepreneurship as a method, which is in contrast to the current waysthe known worldsin which we are currently teaching entrepreneurship. We are not proposing a particular pedagogy. If anything, we would rmly fall in Forest and Petersons (2006) andragogy camp anyway. On the contrary, we are proposing an entirely different approach

56

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

to teaching entrepreneurship. We are proposing an overarching framework for teaching entrepreneurship that will require many different approaches to teaching and learningsome of which have not yet been discovered or created. We are proposing that teaching entrepreneurship requires teaching a method. The method is teachable, learnable, but it is not predictable. The method is peopledependent but not dependent on a type of person. The entrepreneurship method goes beyond understanding, knowing, and talking and demands using, applying, and acting. Most importantly the method requires practice. Entrepreneurship requires practice. Learning a method, we believe, is often more important than learning specic content. In an ever-changing world, we need to teach methods that stand the test of dramatic changes in content and context. We introduce this method in light of other current approaches to teaching entrepreneurship.

The Known Worlds of Entrepreneurship Education

We present three different approaches used to teach entrepreneurship. Some educators rely on one approach, whereas others incorporate two or even all approaches. Though it is tempting to think our worlds represent the evolution of the eld, we do not think of them strictly in chronological order and recognize that each of these approaches is being used in classrooms today.

The Entrepreneur World We have already acknowledged the importance of the entrepreneur in this eld of study. A large amount of literature has developed around the traits approach, much of it starting with the economic development work of David McClelland (1965). Even today, researchers around the world continue to search

for the monolithic personality of the entrepreneur. Brockhaus and Horwitz (1986) reviewed the early trait literature and concluded that there are four major personality traits of individuals: need for achievement, internal locus of control, high risk-taking propensity, and tolerance for ambiguity. Ten years later, Miner (1996) proposed four psychological personality patterns of entrepreneurs: personal advisors, empathetic super salespeople, real managers, and expert idea generators. Also, most recently, Shane posited the role of the entrepreneurial gene, taking the nature versus nurture discussion to new extremes (Mount 2010). Any discussion of the numerous challenges in this trait line of research can range from problems with dening (who is an entrepreneur and who are we picking to represent successful entrepreneurs), differentiating and explaining (these are traits of successful people in many lines of work) to prediction (do we all not wish we could pick the winners)? In this world, the entrepreneur reigns supreme with almost superhero characteristics. We can consider this approach from three perspectives. First, though it is easy to consider this an early world of entrepreneurship, this is not a timebound discussion. Bill Gartner (1988) gave us a notable moment of punctuated equilibrium that prompted many in the eld to move beyond traits, but it is hard to let go. We are also sure that you still hear, as we do, the you cannot teach entrepreneurship mantra at many of the more practitioner-oriented programs you give or attend. Despite our introduction to this essay, we do beg to differ. After all, this same question has been asked about both leaders and teachers (Quinn and Anding 2005). A second consideration of entrepreneurial content in this world is the fact that most of the characteristics studied were identied in research projects in which the samples were entirely white

NECK AND GREENE

57

males. Methodologically, it is hard to support any sort of generalization from that, and none of our worlds of entrepreneurship are exclusively males. Third, this world, especially in the early days, uses a quite narrow denition of successone that is entirely economically based. It is anchored in the smallest denition of entrepreneurship, the creation of a small business, even if it is one that is intended to grow. As Giacalone (2004) reminded us, Teaching students to use the single-minded materialistic value system distorts the reality of daily life, were we routinely assimilate nonmaterialistic goals (p. 416). The nding that entrepreneurs are motivated by more than money is long-standing and quite robust across studies, and yet, we rarely tie the motivation to the entrepreneurs own denitions of success. The entrepreneur is the champion in this world. On the delivery side, as teachers, we use a variety of entrepreneurial assessments, self-examinations, the do you have the right stuff approach. We probe for those characteristics the early research suggested were important, such as locus of control or need for achievement. Many of these are interesting and valid measures but not necessarily precise for identifying entrepreneurs. Then there are some of the others. Two questions we recently found in an online quiz included the responses (and these would be the ones desirable for entrepreneurs): I like to be wild and uninhibited and go fast. I like to act on impulse. Though these may be extreme examples, the tone is not an unusual part of the discussion. One noted professor describes his explicit goal as making his students spines sweat. On a recent trip to Malaysia, one of the authors of this essay saw a grade sheet posted on a bulletin board with the results of an entrepreneurial assessment. How would the teenage recipient of a 60 on his or her assessment think about entrepreneurship in the future. Are we really

ready to screen people out of entrepreneurship though they are still coming into their own? The entrepreneur world is heavily inuenced by a lecture teaching methodology, basically a stand-and-deliver approach. However, we combine this with the use of many guest speakers, selected with a precise list of criteria reecting again in this worlds particular denition of entrepreneur and success. This means that most of our guest speakers tend to be white males who have started and usually grown their businesses. To be fair, over the years, the examples of role models have become somewhat more diverse along some dimensions, but it is a continuing push. The pedagogical implications of the entrepreneur world are a description of the entrepreneur, neatly tting into an observe, describe, and measure approach, supporting categorizations and some correlations but not able to go beyond (Christensen and Carlile 2009). In some sense, our students taught in this world see entrepreneurship as a box in which they either t or do not. Their concern is that they do not have the right stuff/characteristics to be an entrepreneur. As teachers, our choices of entrepreneurial illustrations set up role models and our students often do not see a reection of themselves. The ironic part is that with all this description, picking the winners does not get any easier.

The Process World Low and MacMillan (1988) called for more causal, process-oriented research. Amit, Glosten, and Muller (1993) reviewed core entrepreneurship research challenges and concluded that given the interdisciplinary nature of entrepreneurship, analytical and empirical tools should be borrowed from other disciplines to develop theory around the process of entrepreneurship. The call

58

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

was echoed in Venkataramans (1997) seminal paper on the distinctive domain of entrepreneurship. The inuence of strategy scholars working in the eld coupled with calls for more rigorous and methodically sound studies led scholars to operationalize entrepreneurship as a process with greater emphasis on the organizational level of analysis. The process view extends the reach of entrepreneurship from rm creation to rm exit; thus, there is increased attention given to capital markets, resource allocation, performance, and growth. The process research results found their way into the classroom, and textbooks today take a more process-oriented approach. The process is presented and taught in a linear fashion as one of identifying an opportunity, developing the concept, understanding resource requirements, acquiring resources, implementation, and exit (Morris 1998). We refer to the process world as one of planning and prediction. The analytical approach of teaching opportunity evaluation, feasibility analysis, business planning, and nancial forecasting is the cornerstone for most entrepreneurship curricula today. Perhaps the process world is so popular to teach in because we can. When most agreed that entrepreneurs did not have specic traits, we were motivated to nd processes to teach. Business plan writing and the case method in this world are the preferred pedagogies. In a eld where we argue that there are no right answers, the process world, from an education perspective, is the closest we can get. Though the business planning process is an attractive and powerful learning process, a disproportionate amount of time is spent honing secondary research skills than actually taking smart action in the real world. Any educator that has used the business plan as a major course project (authors included) understands the inner thoughts of students:

Student 1: The longer the plan the better. A long plan indicates more work and a better grade. Student 2: Its the midpoint of the semester and Im convinced my opportunity is not viable but I have to complete the plan because it represents 30% of my grade. I dont have time to start over. Student 3: Once Im nished with this plan on my new bar Im going to mail it to every venture capitalist in the area. The argument for business plan writing can succinctly be summed up in one sentence: the business plan is required for investment. Gumpert (2002), in his entertaining book, Burn Your Business Plan, questioned why we even write business plans. He points to a growing industry of consultants, software designers, and educators that market business plan writing and have created the perception that it is a required document for every entrepreneur. Though the true premise of his book is about developing relationships with a spectrum of investors, his point is duly noted. Even venture capitalists do not want the business plan novels; they want action and proof of concept rst. As educators, we must ask ourselves if we are forcing students to write a business plan too soon. To complement the planning portion of core entrepreneurship courses, the case method is used so students can learn about the various decision options faced by entrepreneurs. The case study is admittedly a powerful tool that allows the center of learning to be with the students; however, the majority of faculty are never adequately trained in the case method. Teaching using the case method takes an extraordinary amount of timeboth in prep as well as in mastery. Christensen (1991) stated that the case discussion teacher has to master questioning, listening, and response;

NECK AND GREENE

59

these skills are inextricably linked, fail to effectively work in isolation, and require teaching exibility and, we would argue, skills of an improvisation artist. The downside of teaching a case without adequate training is that student learning is compromised. A classroom discussion, as engaging as it may be, is not the same as a case study discussion and does not necessarily lead to the accomplishment of learning objectives. The process world in our view is one of prediction. It focuses on a linear process that if followed correctly, will increase the likelihood of venture success. The steps in the process are generally introduced in introductory entrepreneurship courses, then electives are offered to delve deeper into particular steps. For example, classes on opportunity, entrepreneurial marketing, entrepreneurial nance, and managing growth are commonplace and mainstream in the most developed entrepreneurship programs. The problem is that entrepreneurship is neither linear nor predictable, but it is easy to teach as if it were.

The Cognition World Again, let us state that our approach here is not evolutionary or linear, but there is an undeniable time element in that the cognitive approach emerged more recently than our other two worlds. In fact, the cognitive approach has even been described as emerging as a response to the failure of past entrepreneurial personality based research to clearly distinguish the unique contributions to the entrepreneurial process of entrepreneurs as people (Mitchell et al. 2002, p. 93). This description is interesting in that it recognizes not only the earlier research focus on the person but also the role of the entrepreneurial process. The cognitive approach in entrepreneurship is really only about 15 years old and with a few exceptions, has only

started to make its way into the classroom in the last ve years. In this world, we are again focusing on the entrepreneur or the entrepreneurial team but in a quite different way. This newer focus on the person is in a more dynamic way that recognizes the potential for learning how to think entrepreneurially. If we start from Neissers 1967 denition of cognition as the processes that allow sensory inputs to be transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, retrieved, and used, we can then advance, at least for our purposes, to the entrepreneurial cognition approach. Now we look at the knowledge structures that people use to make assessments, judgments, or decisions involving opportunity evaluation, venture creation, and growth (Mitchell et al. 2002, p. 97). As educators, we can work with knowledge structures. The early questions in cognitive entrepreneurship focused on topics such as how do entrepreneurs think and is that a potential competitive advantage? (Mitchell et al. 2002). This approach brings us back to the question of who is the entrepreneur or when is someone an entrepreneur? The more helpful question is how do people think entrepreneurially? This is a much more useful construct to guide our educational and research activities in the eld, recognizing the great diversity in the ways people can be entrepreneurs. We were recently asked quite seriously about the role of gut in teaching entrepreneurship, and it is a very fair question. The mental models underlying the cognitive approach (Krueger 2007) provide us with the ways and means to address such questions, leading toward the potential of providing both skills and increased condence to our students. In this way, our focus expands to include both doing and thinking. So, what and how do we teach in this world? We pay attention to different things, including the decision to become an entrepreneur and how to understand that decision. We investigate the entre-

60

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

preneur and most certainly now include the team. We spend more time on discovery, specically on the identication and exploitation of opportunities, and we explore what we believe to be the central question of this world: how do people think entrepreneurially. Part of our emphasis to guide pedagogy is therefore on the think . . . do. In order to do this, we use cases and simulations, but we use them in a different way. When we focus on the entrepreneur as the protagonist, we are exploring not only the venture process but the decision-making process. Others are using the writing of narratives and scripts using the Mitchell et al. (2000) approach of arrangement, willingness, and ability to further the students understanding of how they process information about entrepreneurship. We also have seen a number of great approaches, exercises, and classes on the search for opportunities, including Jim Fiets systematic search (Fiet and Patel 2006; Nixon et al. 2006) and DeTienne and Chandlers 2004 opportunity identication exercise. Overall, in this world, we are focusing on entrepreneurial decisions and we do it by discussing the role of expert scripts, heuristics, and schema, leading to the construction of entrepreneurial mental models. In summary, the entrepreneur world has clearly informed us that there is no one type of entrepreneur. This means one of the challenges of the cognitive world is to avoid the trap of the entrepreneur world and therefore be able to recognize the richness of a diversity of cognitive approaches, again linked to a diversity of entrepreneurial motivations and desired outcomes or denitions of success. At the same time, with an overreliance on teaching entrepreneurship as a process, the process world appears linear and predictable. Innovation is often absent because we teach and applaud the use of existing business models often arguing that using proven

models reduces the risk of failure. The vast majority of our students plans are not based on a truly innovative product or service. Even more absent is the innovation in business models. This leaves us in the position of largely replicating existing forms of businesses and therefore, even existing kinds of economies. The cognition world is growing in popularity because it recognizes the importance of the mind and the dynamic approach to learning how to think entrepreneurially.

New Frontiers: Entrepreneurship as a Method

Why do we support entrepreneurship as a method? Because a process implies that you will get to a specic destination. Entrepreneurship is often thought of as a processa process of identifying an opportunity, understanding resource requirements, acquiring resources, planning, and implementing. However, the word process assumes known inputs and known outputs as in a manufacturing process. For example, building a car on an assembly line is a manufacturing process. You know all the parts; you know how they t together; and you know the type of car you will have at the end. A process is quite predictable. Entrepreneurship is not predictable. On the other hand, a method represents a body of skills or techniques; therefore, teaching entrepreneurship as a method simply implies that we are helping students understand, develop, and practice the skills and techniques need for productive entrepreneurship. Figure 1 contrasts teaching entrepreneurship as a process and a method. Teaching entrepreneurship as a method requires going beyond understanding, knowing, and talking; it requires using, applying, and acting. Entrepreneurship requires practice. Learning a method may be more important than learning

NECK AND GREENE

61

Figure 1 Process versus Method

Entrepreneurship as a Process Known inputs and outputs Steps Predictive Linear Precision Tested Entrepreneurship as a Method A body of skills or techniques Toolkit Creative Iterative Experimentation Practiced

content. In an ever-changing world, we need to teach methods that stand the test of dramatic changes in content and context. Rather than viewing practical or pedagogical knowledge as derivative of scientic knowledge, it is more appropriate to view practice and teaching as distinct modes of knowing in their own respects (Van de Ven and Johnson 2006). Knowledge of teaching and practice take their place alongside of science as distinct and complementary elements of professional knowledge (Kondrat 1992 in Van de Ven and Johnson 2006). When each of these different kinds of knowledge are together focused on the worlds complex problems, they have the potential to produce a deeper understanding than any one type of knowledge applied alone (Van de Ven and Johnson 2006). Perhaps, this is ultimately the nature of entrepreneurship education. Approaching entrepreneurship as a method means teaching a way of thinking and acting built on a set of assumptions using a portfolio of techniques to encourage creating. The method forces students to go beyond understanding, knowing, and talking. It requires using, applying, and acting. The method requires practice. Therefore, our

underlying assumptions of the method include the following: (1) Applies to novice and experts: the assumption is that the method applies across student populations and works regardless of experience level. What is important is that each student understands how he or she views the entrepreneurial world and his or her place in it. It represents the foundation of the method. (2) The method is inclusive, meaning that the denition of entrepreneurship is expanded to include any organization at multiple levels of analysis. Therefore, success is idiosyncratic and multidimensional. (3) The method requires continuous practice. The focus here is on doing, then learning, rather than learn then do. As a result a reective practice component is incredibly important to learning. (4) The method is for an unpredictable environment. The Method approach rmly recognizes that entrepreneurship is teachable. Similar to the approach to leadership discussed in Quinn and Anding, We can be in a normal, reactive state or an extraor-

62

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

dinary, creative state. Anyone can move from where they are now to a more reactive or more creative state (1999, p. 489). The question is how to do this. For us, it means experimenting with a pedagogical portfolio that emphasizes the dimensions of the method. We suggest a portfolio here that includes starting businesses as part of coursework, serious games and simulations, design-based learning, and reective practice.

(3) Students use information technology (IT) for decision-making and productivity and learn that IT is essential in supporting all areas of a business. (4) Students experience social responsibility and philanthropy through the donation of their time (six hours minimum) and business prots to charitable organizations. Many business schools today have incorporated the real-world practice of business creation into their entrepreneurship curriculum. For example, the 2010 United States Association for Small Business and Entrepreneurship winner for model entrepreneurship course was awarded to Monmouth University for its capstone experience where students work in teams to start businesses. However, as we talk about a pedagogy of practice within the entrepreneurship method, we are advocating for realworld venture creation courses to take place at the beginning and not at the end of entrepreneurship programs. We suggest this because at the undergraduate level, students have little business experience and to truly develop empathy for the entrepreneur, one must experience new venture creation before he or she can study business management or other disciplinary areas. Furthermore, a level of condence is generated from the doing experience and students begin to experience success and failure as well as practice methods for navigating unknown territories. Students experience the ups and downs of entrepreneurship and learn about the sweat equity associated with a start-up. They gain knowledge of the importance of leadership yet struggle with nding and developing their own style. They practice entrepreneurship and through experience, learn about the power of human agency, yet effectively managing and utilizing human resources is more art than science. Students feel defeat after making

Starting Businesses Starting businesses as part of coursework has become more mainstream over the past few years. Babson College, for example, started its Foundations of Management and Entrepreneurship (FME) course in 1996 where rst year, undergraduate students are required to start a business during their rst year at the college. The focus of FME is on opportunity recognition, resource parsimony, team development, holistic thinking, and value creation through harvest. The vehicle of learning is a limited duration business start-up steeped in entrepreneurial thinking and a basic understanding of all functions of business. Because FME is a required course, all rst-year undergraduates experience the entire cycle of entrepreneurship. The course is a blend of theory and practice, which forms the basis for the entire Babson undergraduate core curriculum. The overall purpose of the course is to allow students to practice business and entrepreneurship so the content comes alive. The objectives of the course include:

(1) Students practice entrepreneurship and generate economic and social value. (2) Students understand the nature of business as an integrated enterprise and knowledge of all key business areas is essential in developing a well-rounded business aptitude in preparation for the real world.

NECK AND GREENE

63

poor decisions and experience elation over small wins. In hindsight, they underestimate the role of trust between managers and employees and learn delegation is not a choice. In the end, they nally learn that the best opportunity in the world is of little value without a strong team that can execute. Such strength is derived from open and constant communication, shared but challenging goals, and the ability to adapt in uncertain environments.

Serious Games and Simulations To play or not to play? That is indeed the question. The inuence of computer games and gaming on the rising generations is under investigation with consideration of the applications in both the academic and professional worlds. There is a large variety of denitions of serious games, with most sharing two common grounding assumptions (Greene, Forthcoming). First, there is an element of game usually dened as having rules and a sense of gameplay. Second, there is the expectation of fun. Gaming aligns learning, play, and participations while exposing students to real challenges in a virtual world. Todays games require 50100 hours to master, which equals the amount of time a student spends on a semester-long course (Pink 2006). There is indeed a rising use of games in spaces where simulations were prevalent but with that added expectation of the gameplay and fun elements. We both attended a Serious Game Summit as part of the annual Game Developers Conference and heard the presentations on how Hilton Garden Inn is using games to train its staff on customer service. We learned how Intel uses games for network training, and for one of the most far-reaching examples, how the U.S. Army and the Canadian Army each use computer games and alternative reality games for recruiting and training purposes. Babson, similar to a few other schools, has been investigating and

experimenting with the use of serious games in our entrepreneurship curriculum for some time. To date, our focus has been on three main areas. First, we developed and tested a social media alternative reality game for teaching social media to faculty members. The intent was to help faculty understand what is available, how it can be helpful to entrepreneurs, and how it can be useful in teaching entrepreneurship. The framework of the game was an elaborate treasure hunt that required the faculty/ students to not only visit social media sites but to use each one of them in a way that would benet an entrepreneur (or entrepreneurship student). The ultimate treasure was a hidden chest containing what was labeled Roger Babsons Secret Entrepreneurship Curriculum and was in reality a list of resource materials for teaching serious games. Another one of our game experiments was the use of an off-the-shelf computer game. The Sims, and the expansion packet, Open for Business. The purpose of the game was to compact the business creation process in order to map the creation of organizational culture, particularly through the way the student/ entrepreneur/player used his or her time and his or her money in relation to the business, the employees, and the community. The course is based on a combination of institutional- and resourcebased theories to provide guidance for students in creating culture as a resource. The greatest challenge was to get students to stop playing the game. Finally, we developed a video game to support learning about how entrepreneurs think under conditions of risk, uncertainty, and unknowability. The game is based on the theory of effectuation (Sarasvathy 2008) and is designed to replace a case study for an in-class discussion on entrepreneurial thinking. Overall, the use of serious games is part of the method approach; it allows stu-

64

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

dents a different environment to practice entrepreneurship. It is a playful approach for serious results.

Design-Based Learning The basic argument is that entrepreneurs think, and perhaps act, similar to designers. In our quest to dene, understand, and even measure the entrepreneurial mindset, the world of design is a good starting point for our inquiry. Entrepreneurship is an applied discipline, yet we are teaching and researching as if it was part of the natural sciences (Simon 1996). Furthermore, the impact of entrepreneurship research is limited and little has been performed to assess the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education. Herb Simon argued that applied disciplines are better served by design-based curricula. Design is a process of divergence and convergence requiring skills in observation, synthesis, searching and generating alternatives, critical thinking, feedback, visual representation, creativity, problem-solving, and value creation. Teaching entrepreneurship through a design lens can help students identify and act on unique venture opportunities using a toolkit of observation, eldwork, and understanding value creation across multiple stakeholder groups. At the core of entrepreneurship is the identication and exploitation of opportunities (Shane and Venkataraman 2000), yet the majority of entrepreneurship courses assume that the opportunity has been identied. In the process world, we talked about case studies and business plan writing. The majority of entrepreneurship case studies focus on opportunity evaluation, but little attention is given to how the opportunity was identied beyond a surface-level discussion related to the life history of the entrepreneur. In a traditional business plan course, very little time is given to practicing tools of creativity and idea generation. Overall, very little is done to train a

student to think more entrepreneurially and creatively participate in opportunity discovery. We argue that such a discovery process should be grounded in fundamental design principles so students are equipped with tools to not only nd opportunities but to also make opportunities (Sarasvathy 2008).

Reective Practice The idea of encouraging reection is certainly not new, and if anything, is regaining its currency as a critical component of the overall learning experience. From Socrates, through Thoreau to the present day, the emphasis on taking time to think often resonates and yet seems difcult to inject into an actionbased curriculum in an overarching and meaningful manner. For many of our students, simply sitting still and thinking does not come naturally or easily, and yet, the power of the potential outcomebeing aware of our actions so we can evaluate them (Brockbank and McGill 2007, p. 85) seems clear. Reection is an important process by which knowledge is developed from experience. When reecting, one considers an experience that has happened and tries to understand or explain it, which often leads to insight and deep learningor ideas to test on new experiences. Reection is particularly important for perplexing experiences, working under conditions of high uncertainty, and problem-solving. As a result, it should not be a surprise that reection is an integral component of entrepreneurship education and also a way of practicing entrepreneurship. Donald Schn (1983, 1987) coined the term reective practice while studying applied university programs such as medicine, law, and architectural design. He argued that the knowledge acquired through coursework, what he called propositional knowledge, was limited in its impact because it did not take into consideration the reality of practice. Yet,

NECK AND GREENE

65

he discovered that professionals graduating from applied programs were still effective despite how they were taught. Schn learned that professionals enhanced their practice through engagement and developed practice experience (Brockbank and McGill 2007). Schn distinguished reection-onpractice (dolearnthink as a process) from reection-in-practice (dolearn think as a behavior). Both are important and represent a continuous cycle of learning. Schn found the teachers and students engaged in reection on emergent practice that was to underpin their learning and therefore enhance their practice. Putting it more simply, students learned by listening, watching, doing and by being coached in their doing. Not only did they apply what they had heard and learned from lectures, books, and demonstrations but when they did an action that was part of their future profession, for example using a scalpel, they also learned by reecting themselves and with their [teachers], how the action went. They reected on their practice. In addition, they would take with them that reection on their previous actions as a piece of knowledge or learning when they went into the action the next time. Thus in the next action they would be bringing all their previously acquired understanding and practice and be able to reect in the action as they did it, particularly if a new circumstance came up. (Brockbank and McGill 2007, p. 87) Given the nature of entrepreneurship as a continuous cycle of action, learning, testing, and experimenting, developing students as reective entrepreneurs

requires reection-on-practice and reection-in-practice as part of a pedagogy portfolio. A primary objective of reection is deep learning. Marton (1975) categorized learning as surface or deep. Surface learning is associated with a more passive approach that is premised on a model of education that is dependent on learning, absorbing, and regurgitating. Deep learning is associated with a more active approach characterized by a desire to grasp and synthesize information for valuable and long-term meaning.

Conclusions

There is agreement, at least in theory but not in practice, that entrepreneurship courses should be taught differently from the traditional management courses (Vesper and McMullen 1988). Kent (1990) even stated that entrepreneurship education must be entrepreneurial (p. 284), whereas early writings by Plaschka and Welsch (1990) pointed to emerging structures in entrepreneurship education: As the criticisms of business education show, current analyticalfunctional quantitative, toolsoriented, theoretical, left-side of the brain, overspecialized, compartmentalized, approaches are not adequate to begin solving illdened, unstructured, ambiguous, complex multidisciplinary, holistic, real world problems. (p. 61) Table 1 summarizes the known worlds (entrepreneur, process, cognition) that we teach in today as well as the new frontier presented here entrepreneurship as a method. Our purpose was to acknowledge that we teach in several different worlds. Many teach in more than one world, but the environment for entrepreneurship is changing whereas education for entrepreneurship is not. We are living in a

66

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

Table 1 Known Worlds and New Frontiers

Process World Planning and prediction New venture creation Decision-making to engage in entrepreneurial activity Entrepreneur and team Cases, simulations, scripting Thinking and doing Cognition World Method World Value creation Portfolio of techniques to practice entrepreneurship Entrepreneur, team, and rm Serious games, observation, practice, reection, cocurricular, design Expert scripts, heuristics and decision-makings, schema, mental models, knowledge structures Decision Practice, self-knowledge, t, action, dolearn, cocreation, create opportunities, expect and embrace failure Action

Entrepreneur World

World of . . .

Heroes, myths, and personality proling

Focus

Traits; nature versus nurture

Level of Analysis Cases, business plans, business modeling

Entrepreneur

Firm

NECK AND GREENE Hockey stick projections, capital markets, growth, resource allocation, performance Prediction

Primary Pedagogy

Business basics, lectures, exams, assessment

Language

Locus of control, risk-taking propensity, tolerance for ambiguity, n-ach

Pedagogical Implications

Description

67

world characterized by increasingly greater levels of uncertainty and even unknowability. We are advocating for an entrepreneurship method approach for three reasons: First, entrepreneurship education is incredibly important, but current, mainstream approaches are dated. Second, real-world experience contributes signicantly to learning, but sometimes, the cost of failing in the real world is too high. Finally, and because of points 1 and 2, entrepreneurship within a formal education structure requires a new approach based on action and practice. As you can see from our example pedagogy portfolio, the method is teachable, learnable, but it is not predictable. Starting businesses help students feel what it is like to assume the role of an entrepreneur. Serious games and simulations allow students to play in virtual worlds that mirror reality. Designed-based learning encourages student to observe the world through a different lens and create opportunities. Finally, reective practice gives permission to our students to take time, think, and absorb the learning of their practice-based curriculum. Together, our portfolio of feeling, playing, observing, creating, and thinking is the entrepreneurship method and a prescription for practice. The method is people-dependent but not dependent on a type of person. The entrepreneurship method goes beyond understanding, knowing, and talking and demands using, applying, and acting. Most importantly, the method requires practice. Entrepreneurship requires practice. Learning a method, in our opinion, is often more important than learning specic content. In an ever-changing world, we need to teach methods that stand the test of dramatic changes in content and context. At the end of the day, perhaps we do not teach entrepreneurship the discipline. Perhaps we teach a method to navigate the discipline.

References

Amit, R., L. Glosten, and E. Muller (1993). Challenges to Theory Development in Entrepreneurship Research, Journal of Management Studies 30(5), 815834. Anding, J. (2005). An Interview with Robert E. Quinn. Entering the Fundamental State of Leadership: Reections on the Path to Transformational Teaching, Academy of Management Learning & Education 4(4), 487495. Brockbank, A., and I. McGill (2007). Facilitating Reective Learning in Higher Education, 2nd ed. New York: Open University Press. Brockhaus, R., and P. Horwitz (1986). The Psychology of the Entrepreneur, in The Art & Science of Entrepreneurship. Eds. D. Sexton and R. Smilor. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 2548. Brush, C. G., I. M. Duhaime, W. B. Gartner, A. Steward, J. A. Katz, M. A. Hitt, S. A. Alvarez, G. D. Meyer, and S. Venkataraman (2003). Doctoral Education in the Field of Entrepreneurship, Journal of Management 29(3), 309331. Christensen, C. M., and P. R. Carlile (2009). Course Research: Using the Case Method to Build and Teach Management Theory, Academy of Management Learning & Education 8(2), 240251. Christensen, C. R. (1991). The Discussion Teacher in Action: Questioning, Listening, and Response, in Education for Judgment: The Artistry of Discussion Leadership. Eds. C. Roland Christensen, D. A. Garvin, and A. Sweet. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 153174. DeTienne, D., and G. Chandler (2004) Opportunity Identication and Its Role in the Entrepreneurial Classroom: A Pedagogical Approach and Empirical Test, Academy of Management Learning and Education 3(3), 242257.

68

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

Fiet, J. O., and P. C. Patel (2006). Entrepreneurial Discovery as Constrained, Systematic Search, Small Business Economics 30, 215229. Forest, S., and T. Peterson (2006). Its Called Andragogy, Academy of Management Learning & Education 5(1), 113122. Gartner, W. B. (1988). Who Is an Entrepreneur? Is the Wrong Question, American Journal of Small Business 12(4), 1132. Giacalone, R. A. (2004). A Transcendent Business Education for the 21st Century. Academy of Management Learning & Education 3(4), 487 495. Greene, P. G. (forthcoming). The Emergence of the Serious Game Industry, ISBE Annual Conference, Liverpool, Oct 2009. Gumpert, D. E. (2002). Burn Your Business Plan! Needham, MA: Lauson Publishing. Kent, C. A. (1990). Introduction: Educating the Heffalump. Entrepreneurship Education: Current Developments, Future Directions. New York: Quorum Books. Kondrat, M. E. (1992). Reclaiming the Practical: Formal and Substantive Rationality in Social Work Practice, Social Service Review 166, 237255. Krueger, N. R. (2007). What Lies Beneath? The Experiential Essence of Entrepreneurial Thinking, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31(1), 123138. Low, M. B., and I. C. MacMillan (1988). Entrepreneurship: Past Research and Future Challenges, Journal of Management 14(2), 139161. Marton, F. (1975). What Does It Take to Learn? in How Students Learn. Eds. N. Entwistle and D. Hounsell. Lancaster: Institute for Research and Development in Post Compulsory Education, 125138. McClelland, D. (1965). Need Achievement and Entrepreneurship: A Longi-

tudinal Study, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1, 389392. Miner, J. B. (1996). The 4 Routes to Entrepreneurial Success. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler. Mitchell, R. K., L. Busenitz, T. Lant, P. McDougall, E. A. Morse, and B. Smith (2002). Toward a Theory of Entrepreneurial Cognition: Rethinking the People Side of Entrepreneurship Research, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27, 93104. Mitchell, R. K., J. B. Smith, K. W. Seawright, and E. A. Morse (2000). CrossCultural Cognitions and the Venture Creation Decision, Academy of Management Journal 53(5), 974993. Morris, M. H. (1998). Entrepreneurial Intensity: Sustainable Advantages for Individual, Organizations, and Societies. Westport, CT: Quorum. Mount, I. (2010). Nature vs. Nurture: Are Great Entrepreneurs Born . . . Or Made? Fortune Small Business, December 09/January 10, 2526. Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Nixon, R. D., K. Bishop, Van G. H. Clouse, and B. Kemelgor (2006). Prior Knowledge and Entrepreneurial Discovery: A Classroom Methodology for Idea Generation, International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education 4, 1936. Pink, D. (2006). A Whole New Mind. New York: Riverhead Books. Plaschka, G. R., and H. P. Welsch (1990). Emerging Structures in Entrepreneurship Education: Curricular Designs and Strategies, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 14(3), 5571. Sarasvathy, S. D. (2008). Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. Schon, D. (1983). The Reective Practitioner. New York: Basic Books. (1987). Educating the Reective Practitioner. London: Jossey-Bass. Shane, S., and S. Venkataraman (2000). The Promise of Entrepreneurship as

NECK AND GREENE

69

a Field of Research, Academy of Management Review 25(1), 217227. Simon, H. A. (1996). The Sciences of the Articial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Van de Ven, A. H., and P. E. Johnson (2006). Knowledge for Theory and Practice, Academy of Management Review 31(4), 802821. Venkataraman, S. (1997). The Distinctive Domain of Entrepreneurship

Research, in Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth. Eds. G. T. Lumpkin and J. Katz. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 119 138. Vesper, K. H., and W. E. McMullen (1988). Entrepreneurship: Today Courses, Tomorrow Degrees? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 13(1), 713.

70

JOURNAL OF SMALL BUSINESS MANAGEMENT

Вам также может понравиться

- Assignment Sheet - Analytical ReportДокумент2 страницыAssignment Sheet - Analytical Reportapi-206154145100% (1)

- Digital Marketing Strategy ReportДокумент12 страницDigital Marketing Strategy Reportcyrax 3000Оценок пока нет

- Cadbury ReportДокумент7 страницCadbury ReportSumeet GuptaОценок пока нет

- Tesco Case StudyДокумент8 страницTesco Case StudyWenuri KasturiarachchiОценок пока нет

- Scei ModelДокумент9 страницScei ModelCalistus Eugene FernandoОценок пока нет

- Final Examination (21355)Документ13 страницFinal Examination (21355)Omifare Foluke Ayo100% (1)

- Successful Application of Organ BehaviorДокумент4 страницыSuccessful Application of Organ BehaviorcascadedesignsОценок пока нет

- Technopreneurship marketing plan summaryДокумент5 страницTechnopreneurship marketing plan summaryKeith Tanaka MagakaОценок пока нет

- Keller's Brand Equity ModelДокумент7 страницKeller's Brand Equity ModelVM100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Employee Training and DevelopmentДокумент20 страницChapter 1 Introduction To Employee Training and DevelopmentSadaf Waheed100% (1)

- A Study On Tata Consultancy ServicesДокумент4 страницыA Study On Tata Consultancy Servicesarun kumarОценок пока нет

- Consumer Behavior Group Platform EditedДокумент23 страницыConsumer Behavior Group Platform EditedAvijit ChakrabortyОценок пока нет

- Knowledge Creation Process PPT at Bec Doms Bagalkot MbaДокумент14 страницKnowledge Creation Process PPT at Bec Doms Bagalkot MbaBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)Оценок пока нет

- Kidzania Shaping A Strategic Service Vision For The FutureДокумент34 страницыKidzania Shaping A Strategic Service Vision For The FutureAdrian NewОценок пока нет

- Leadership Skills of Satya NadellaДокумент3 страницыLeadership Skills of Satya NadellaSai PrasannaОценок пока нет

- Case 3 Aviall Inc PDFДокумент2 страницыCase 3 Aviall Inc PDFRamzan IdreesОценок пока нет

- Evolution of ConceptДокумент23 страницыEvolution of ConceptAndra NeculaОценок пока нет

- Inside IDLC Finance - Management Strategy AnalysisДокумент37 страницInside IDLC Finance - Management Strategy Analysisabdullah islamОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ29 страницChapter 1Mai Lê NguyễnОценок пока нет

- Resume of Sultan Mahmud (1) - Converted757Документ3 страницыResume of Sultan Mahmud (1) - Converted757Sukanto DebnathОценок пока нет

- Human Resource Management at Microsoft: Recruitment and Selection - in The BeginningДокумент5 страницHuman Resource Management at Microsoft: Recruitment and Selection - in The BeginningJayanta 1Оценок пока нет

- Assignment#1 Leadership Skills Analysis INDIVIDUAL 4Документ3 страницыAssignment#1 Leadership Skills Analysis INDIVIDUAL 4Ehigie MOMODUОценок пока нет

- Daily Perc Business Plan SummaryДокумент37 страницDaily Perc Business Plan SummaryAnchit Bhagat0% (1)

- Chapter 07 SMДокумент25 страницChapter 07 SMTehniat HamzaОценок пока нет

- VRIO FinalДокумент26 страницVRIO FinalNicole Villamil AntiqueОценок пока нет

- HaldiramДокумент72 страницыHaldiramGuman SinghОценок пока нет

- Sharon Bell Courses Fall 2013Документ5 страницSharon Bell Courses Fall 2013Sumenep MarketingОценок пока нет

- Digital Transformation in TQMДокумент26 страницDigital Transformation in TQMHarsh Vardhan AgrawalОценок пока нет

- Chapter 3 - Goals Gone Wild The Systematic Side Effects of Overprescribing Goal SettingДокумент10 страницChapter 3 - Goals Gone Wild The Systematic Side Effects of Overprescribing Goal SettingAhmed DahiОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Human Capital Development in Puerto RicoДокумент27 страницAnalysis of Human Capital Development in Puerto RicoMohamad Shahhanaz NazarudinОценок пока нет

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityДокумент7 страницCorporate Social ResponsibilitySri KanthОценок пока нет

- Case Study of StarbucksДокумент3 страницыCase Study of StarbucksAnonymous MZRzaxFgVLОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of The Trends and Issues in Entrepreneurship EducationДокумент9 страницAn Analysis of The Trends and Issues in Entrepreneurship EducationAkporido Aghogho100% (1)

- Strategic Capability StarbucksДокумент13 страницStrategic Capability StarbucksBiren67% (3)

- Why Google Is So Successful?Документ4 страницыWhy Google Is So Successful?Eirini TougliОценок пока нет

- What Are The Key Elements of Jetblue and Azul'S Culture ?Документ1 страницаWhat Are The Key Elements of Jetblue and Azul'S Culture ?Nguyễn ThưОценок пока нет

- New Product Development Unit 1Документ22 страницыNew Product Development Unit 1Vinod MohiteОценок пока нет

- Dell IHRM PresentationДокумент16 страницDell IHRM PresentationLilyMSUОценок пока нет

- Knowledge Management at The World Bank 081218Документ14 страницKnowledge Management at The World Bank 081218Fatin NabihahОценок пока нет

- Apple Company Leadership Change - Edited 1 .EditedДокумент13 страницApple Company Leadership Change - Edited 1 .EditedFun Toosh345Оценок пока нет

- Case study on improving Computer Networking educationДокумент2 страницыCase study on improving Computer Networking educationVIJAY KОценок пока нет

- Impact of Western Culture in BangladeshДокумент10 страницImpact of Western Culture in BangladeshNaimul KaderОценок пока нет

- Research Notes - JassДокумент3 страницыResearch Notes - Jassaries usamaОценок пока нет

- Leadership ManagementДокумент17 страницLeadership ManagementLugo Marcus100% (1)

- eBay's 10 OM Areas & Productivity MeasuresДокумент41 страницаeBay's 10 OM Areas & Productivity MeasuresbusinessdatabasesОценок пока нет

- MHR 722 Entrepreneurial ManagementДокумент14 страницMHR 722 Entrepreneurial ManagementParasPratapSinghОценок пока нет

- Downloadable Solution Manual For Basic Marketing Research 4th Edition Naresh K Malhotra Case 2.2 Baskin Robbins Case v5 1Документ6 страницDownloadable Solution Manual For Basic Marketing Research 4th Edition Naresh K Malhotra Case 2.2 Baskin Robbins Case v5 1hh ggjОценок пока нет

- Docebo E Learning Trends 2019Документ44 страницыDocebo E Learning Trends 2019John WickОценок пока нет

- Ebscohost - Creating Shared ValueДокумент28 страницEbscohost - Creating Shared ValueMario Cardona RojasОценок пока нет

- Corporate University: Glorified Training Departments or More?Документ8 страницCorporate University: Glorified Training Departments or More?Allen AlfredОценок пока нет

- Ajeeth Pingle Brand Extention PlanДокумент17 страницAjeeth Pingle Brand Extention PlanAjeeth PingleОценок пока нет

- Managing People in Organisations Assignment 2 (HRMДокумент3 страницыManaging People in Organisations Assignment 2 (HRM郭杰Оценок пока нет

- Rocking The Daisies - 2011 & 2012 - Case StudyДокумент6 страницRocking The Daisies - 2011 & 2012 - Case StudyPooja ShettyОценок пока нет

- How To Write A Culture First Employee Handbook PDFДокумент15 страницHow To Write A Culture First Employee Handbook PDFAnonymous 3cJVrumSXcОценок пока нет

- The Strategy of Starbucks and It's Effectiveness On Its Operations in China, A SWOT AnalysisДокумент7 страницThe Strategy of Starbucks and It's Effectiveness On Its Operations in China, A SWOT AnalysisIrsa SalmanОценок пока нет

- Managing Britannia: Culture and Management in Modern BritainОт EverandManaging Britannia: Culture and Management in Modern BritainРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- 4 PsДокумент11 страниц4 PsLowell ValienteОценок пока нет

- Role of Creativity and Innovation in Entrepreneur SMEsДокумент9 страницRole of Creativity and Innovation in Entrepreneur SMEsPeter NgetheОценок пока нет

- Impact of Culture on the Transfer of Management Practices in Former British Colonies: A Comparative Case Study of Cadbury (Nigeria) Plc and Cadbury WorldwideОт EverandImpact of Culture on the Transfer of Management Practices in Former British Colonies: A Comparative Case Study of Cadbury (Nigeria) Plc and Cadbury WorldwideОценок пока нет

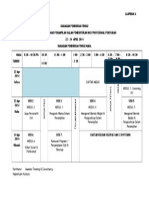

- 38 - Full Schedule Sea GamesДокумент1 страница38 - Full Schedule Sea GamesdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Kolej Profesional MARA Beranang: Chapter 13: Organizational CultureДокумент2 страницыKolej Profesional MARA Beranang: Chapter 13: Organizational CulturedmaizulОценок пока нет

- Guidelines Project Work 2014-15 PDFДокумент9 страницGuidelines Project Work 2014-15 PDFdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Tracer Study-Report (DBS)Документ28 страницTracer Study-Report (DBS)dmaizulОценок пока нет

- Case Study Student Leader Training-Part 3Документ84 страницыCase Study Student Leader Training-Part 3dmaizulОценок пока нет

- Task 1: September 2016 Before 1.00pmДокумент1 страницаTask 1: September 2016 Before 1.00pmdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Senarai Nama Usahawan Dropship: Nama: Nama Perniagaan / Syarikat: No. Telefon: Alamat Email: Produk DropshipДокумент1 страницаSenarai Nama Usahawan Dropship: Nama: Nama Perniagaan / Syarikat: No. Telefon: Alamat Email: Produk DropshipdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Quotation KPM BeranangДокумент1 страницаQuotation KPM BeranangdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Akta 709 PDFДокумент17 страницAkta 709 PDFdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Kolej MARA Beranang Digital Entrepreneurship Report S4&5Документ6 страницKolej MARA Beranang Digital Entrepreneurship Report S4&5dmaizulОценок пока нет

- The Development of Transformational Leadership Amongst The Iban Community Leaders in The Three Resettlement Areas in Kanowit District, SarawakДокумент132 страницыThe Development of Transformational Leadership Amongst The Iban Community Leaders in The Three Resettlement Areas in Kanowit District, Sarawakdmaizul100% (1)

- Notaku 1Документ39 страницNotaku 1dmaizul0% (1)

- ReceiptДокумент1 страницаReceiptdmaizulОценок пока нет

- ImejДокумент1 страницаImejdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Bi PSMДокумент13 страницBi PSMdmaizulОценок пока нет

- PrsentationДокумент1 страницаPrsentationdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Umi Umd 5810Документ121 страницаUmi Umd 5810dmaizulОценок пока нет

- ImejДокумент1 страницаImejdmaizulОценок пока нет

- BabyДокумент1 страницаBabydmaizulОценок пока нет

- 2 Components of ETAДокумент3 страницы2 Components of ETAdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Stress ManagementДокумент11 страницStress ManagementdmaizulОценок пока нет

- Cash Otflow 25-26 JuneДокумент2 страницыCash Otflow 25-26 JunedmaizulОценок пока нет

- Jul - Dec 09Документ8 страницJul - Dec 09dmaizulОценок пока нет

- The Behavioural Science Annual - Online - 2Документ33 страницыThe Behavioural Science Annual - Online - 2David HinojosaОценок пока нет

- Sublimation, Culture, Creativity PDFДокумент29 страницSublimation, Culture, Creativity PDFmarianaОценок пока нет

- ShazeДокумент1 страницаShazeFarshid DaruwallaОценок пока нет

- Conducting A WorkshopДокумент19 страницConducting A WorkshopAnand GovindarajanОценок пока нет

- Saint Joseph College of Sindangan IncorporatedДокумент16 страницSaint Joseph College of Sindangan IncorporatedChrisLord Agpalo BugayОценок пока нет

- MINAДокумент20 страницMINAMax SchleserОценок пока нет

- INFJДокумент8 страницINFJhelen_lai_18100% (10)

- Exploring Music Therapy For Filipino Autistic Children: Marisa MarinДокумент34 страницыExploring Music Therapy For Filipino Autistic Children: Marisa MarinNikki CrystelОценок пока нет

- Problems of Psychology in The 21st Century, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2016Документ57 страницProblems of Psychology in The 21st Century, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2016Scientia Socialis, Ltd.Оценок пока нет

- Ok 936860629 Ok 11 Yds Mart 2019Документ25 страницOk 936860629 Ok 11 Yds Mart 2019gizemcetinОценок пока нет

- 1991 9986754Документ18 страниц1991 9986754macОценок пока нет

- Tom Cosm - Ten Ways To Keep The Creative Juices FlowingДокумент34 страницыTom Cosm - Ten Ways To Keep The Creative Juices FlowingMia Von KlinkerhöffenОценок пока нет

- Art of Powerful QuestionsДокумент18 страницArt of Powerful QuestionsDaisy100% (49)

- Ikea AnalysisДокумент22 страницыIkea AnalysisGayan Laknatha AriyarathnaОценок пока нет

- Saido 2018Документ21 страницаSaido 2018hajra yansaОценок пока нет

- Markus Orlovsky SpeechДокумент3 страницыMarkus Orlovsky Speechattila_dankuОценок пока нет

- Imaginarium Unlocking The Creative Power WithinДокумент27 страницImaginarium Unlocking The Creative Power WithinShacory HammackОценок пока нет

- Council of Architecture: Minimum Standards of Architectural Education Regulations, 2017Документ38 страницCouncil of Architecture: Minimum Standards of Architectural Education Regulations, 2017Saurav SharmaОценок пока нет

- Workflow Creativity v2 PDFДокумент139 страницWorkflow Creativity v2 PDFBrett Doc Hocking67% (3)

- Rubrics For The Unit Project: Subject: Chemistry Class: 7Документ16 страницRubrics For The Unit Project: Subject: Chemistry Class: 7Altamash KhanОценок пока нет

- ADEC - Al Yasat Privae School 2016 2017Документ22 страницыADEC - Al Yasat Privae School 2016 2017Edarabia.comОценок пока нет

- Group PresentationДокумент11 страницGroup Presentationapi-697299769Оценок пока нет

- Ucsp 11 - WLP 2022-2023Документ18 страницUcsp 11 - WLP 2022-2023Lea Camille PacleОценок пока нет

- ST. VINCENT DE FERRER COLLEGE COURSE SYLLABUS IN SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND SOCIETYДокумент19 страницST. VINCENT DE FERRER COLLEGE COURSE SYLLABUS IN SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND SOCIETYJustine FloresОценок пока нет

- Definition of Terms: What Is A Test?Документ21 страницаDefinition of Terms: What Is A Test?Oinokwesiga PinkleenОценок пока нет

- G.D. TopicsДокумент67 страницG.D. TopicsNaveen Kuram0% (1)

- Teaching Model For Integrating CreativityДокумент1 страницаTeaching Model For Integrating CreativitySPOОценок пока нет

- Tulalip Community Policing PrinciplesДокумент3 страницыTulalip Community Policing PrinciplesEmptii BautistaОценок пока нет

- Work Values and Stress Levels of Selected Displaced Filipino Workers of COVID-19 PandemicДокумент9 страницWork Values and Stress Levels of Selected Displaced Filipino Workers of COVID-19 PandemicPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalОценок пока нет

- Week 2 - Types of EntrepreneurДокумент18 страницWeek 2 - Types of EntrepreneurAshly MateoОценок пока нет