Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Ekinci e Riley 2001 - Validating Quality Dimensions - Cópia

Загружено:

Rafael Pantarolo VazИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ekinci e Riley 2001 - Validating Quality Dimensions - Cópia

Загружено:

Rafael Pantarolo VazАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Pergamon www.elsevier.

com/locate/atoures

Annals of Tourism Research, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 202223, 2001 7 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Printed in Great Britain 0160-7383/00/$20.00

PII: S0160-7383(00)00029-3

VALIDATING QUALITY DIMENSIONS

Yuksel Ekinci Michael Riley University of Surrey, UK

Abstract: This article is primarily methodological and is concerned with the psychological dimensions which form the basis of evaluative judgment on hotels. The study takes six dimensions which have empirical and conceptual support in the literature and attempts to validate them using methods which are different from the now common measuring procedures in this area. The methods applied are Q-Methodology and Guttman procedure. The study highlights the special properties of these methods and shows their utility in hotel evaluation. Of the six dimensions tested only three were found to be valid. Keywords: hotel evaluation, service quality, Guttman Procedure, Q-Methodology, validity. 7 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. sume : La validation des dimensions de qualite . Le pre sent article est surtout Re thodologique, se rapportant aux dimensions psychologiques qui forment la base des me tels. L'e tude prend six dimensions qui sont appuye es jugements evaluatifs des ho rature et essaie de les valider en utilisant empiriquement et conceptuellement dans la litte thodes qui sont diffe rentes des proce dures de mesurage qui sont de ja courantes dans des me thodes qu'on applique sont la me thodologie Q et la proce dure Guttman. ce domaine. Les me tude souligne les proprie te s spe ciales de ces me thodes et montre leur utilite pour L'e valuation des ho tels. Sur les six dimensions qu'on a essaye es, on en a trouve seulement l'e s: tels, qualite de service, proce dure Gutttrois qui etaient valides. Mots-cle evaluation des ho thodologie Q, validite . 7 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. man, me

INTRODUCTION The subject at the center of this methodological study is the evaluation of hotels. Here, hotel evaluation is placed within the literature of service quality and is used as a specic context in which to focus on the question of the existence and functioning of dimensions of evaluation. The literature on service quality and its measurement, which has its roots in psychology, marketing, and operational management, is extensive and includes studies in tourism and hospitality. One of the strongest themes within this literature is the function of psychological constructs or dimensions in the individual's process of evaluation. This study concentrates on these psychological dimensions and attempts to re-examine and re-test

Yuksel Ekinci (Ph.D.) is Lecturer in the School of Management Studies for the Service Sector, University of Surrey (Guildford, Surrey GU2 5XH, UK. Email < yukselekinci@hotmail.com >). His research interests include consumer behavior, and marketing research, with articular research interests in the measurement of service quality and consumer values. Michael Riley (Ph.D.) is Professor of Organizational Behavior at the same school and university. His research interests include tourism employment and skill accumulation patterns.

202

EKINCI AND RILEY

203

some of the past mainstream empirical ndings by using different methodologies to which other validity analyses are then applied. The approaches are Guttman scaling procedure and QMethodology. Using nominated criteria, the study selects a set of established dimensions and applies a different scaling procedure. The rationale for looking again at established dimensions is that they have not displayed a high level of reliability and validity.

THE MEASUREMENT OF SERVICE QUALITY The literature on service quality displays a number of important conceptual and methodological issues which it attempts to resolve, such as the problem of conceptually differentiating consumer satisfaction, or the role of expectations (Buttle 1996; Ekinci and Riley 1998; Oh and Parks 1997). However, at the heart of the concept of an evaluation process is a set of sequential assumptions, which begin with the notion that the process of perception and evaluation is governed by cognitive functioning. The latter is built upon a structure or cognitive schema which governs how one categorizes and evaluates the world. In other words, there is an antecedent structure which inuences evaluative judgments (Tajfel 1978). It follows logically that the dimensions for the evaluation of service quality lie within this basic cognitive structure. From this platform it is then assumed that evaluation is likely to be based on more than one dimension and that there will be a structure of related ones at work. To a degree, this assumption is supported by empirical studies, in that the process was found to be multi-dimensional (Carmen 1990; Cronin and Taylor 1992; Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry 1985). The structure and relationships among the dimensions are the focus of a number of models. A central thrust of the empirical literature, in relation to these and associate modeled relationship, is to question whether the dimensions of evaluation are generic, in the sense that they would apply to all salient service situations, or specic to a single context. It is the genericspecic issue and the multi-dimensional character which have created the empirical drive within the literature to nd and validate such dimensions. There is a suspicion in the empirical studies that either the dimensions themselves did not exist, or that the scaling did not capture the level of abstraction at which they were being utilized (Vogt and Fesenmaier 1995). In general, the empirical studies indicate that, on the one hand, when service quality models were used, only some of the anticipated dimensions were found (Saleh and Ryan 1991) and occasionally subjects composite the anticipated dimensions into new ones (Mels, Boshoff and Nel 1997). On the other hand, in studies where bunches of service attributes were used instead of nominated dimensions, completely unexpected dimensions were found (Lewis 1984a; Oberoi 1989).

204

HOTEL EVALUATION

To an extent, the conceptual and methodological problems which infect quality measurement in general are reected in the most commonly used instrument SERVQUAL. This questionnaire claims to measure service quality in any type of service organization on ve dimensions: tangibles, reliability, assurance, responsiveness, and empathy(Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry 1988). Despite being rened over a period of years (Parasuraman, Berry and Zeithaml 1991; Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry 1994), SERVQUAL continues to display a lack of consistency in replicating these dimensions in different service environments (Babakus and Mongold 1992; Finn and Lamb 1991; Saleh and Ryan 1991). This unreliability also inhabits other scales which measure quality. What these instruments are failing to capture is the antecedent structure of an individual's evaluative process. It is the uncertain performance of these applications, all of which use Likert scales and the extension of probability modeling, which forms the rationale for this study. The problem of inconsistency is addressed by applying Q-Methodology and Guttman scaling as an alternative procedure. The thrust here is to test whether selected dimensions are scalable. It is a conrmatory process in which the methodology seeks the validity of generic evaluative dimensions in the particular context of hotels. What is being attempted is to recover a selected number of those dimensions by a methodology different from those which created them in the rst place. The approach starts from atomized individual dimensions, selected from the literature, and initially makes no assumptions about the relationship among them. In other words, it begins with nominated dimensions which it seeks to substantiate, and only later postulates their relationship. As the study aims to establish the validity and reliability of these dimensions, it is important to state the criteria that would be regarded as evidence. Reliability is ``the relative absence of errors of measurement in a measuring instrument'' (Kerlinger 1992:405). The reliability of scales is checked by an error assessment procedure at the stage of the Guttman analysis, and by the stability of scales when using two different samples. The concept of validity addresses the question of whether the scale measures what is intended to do. Establishing this consists of different stages: face validity, content validity, construct validity, predictive validity (Kerlinger 1992). In this study, the evidence for face and content validity is derived from both content analyses of scale items and through Q-sort procedure. Unidimensionality, which is the evidence for ``the existence of a single trait or dimension underlying a set of observed measures'' (Hattie 1985), is achieved through a Guttman procedure. The discriminant validity between the dimensions is initially checked through the Q-sort procedure and then investigated by a correlation test. All these support construct validity. The predictive validity is based on some behavioral questions.

EKINCI AND RILEY

205

The Rationale for Q-Methodology and Guttman Scaling At the outset of the research the status of the hypothesized dimensions is that of a ``latent variable or construct'' (DeVellis 1991). Most of the dimensions nominated by models of quality have ``common sense validity'' in that they accord with daily observation; but this is not enough. When the researcher is armed only with a suspicion and a few observations that a social entity exists, and when faced with the complication that, even if it were established, it could be described in a variety of ways, the technique required is one that captures subjectivity. These are the circumstances that can benet from Q-Methodology. Exploratory work, where subjective judgments of an indescribable object are the order of the day, exactly suits the methodology and its procedure, Q-sort technique (Stephenson 1953). This very versatile procedure is often directed at priorities and suspected rank orders (Tractinsky and Jarvenpaa 1995). It is especially suited to cases where the very existence of concepts has not been established and where, in addition, the concepts are postulated to be multidimensional in character. Evaluation of service quality would t this prole. In fact this process was, on reection, suggested by Parasuraman et al (1991:443) when the factor analysis on SERVQUAL data failed to discriminate. The free sort test they suggest amounts to an ``after-the-fact'' Qsort technique. Techniques related to cognition, such as Repertory Grid, can capture objects in the mind and their relationship to each other; however, these cognition based approaches carry the assumption of a schema that can be retrieved. In a sense, Personal Construct Theory, which is the basis of repertory grid, shares the same territory as Q-Methodology but with some important differences. The most important difference is the assumption of well worn ``channels'' in the mind that can only have been put there by experience (Kelly 1955). For example, in the case of evaluating hotels, if subjects were professional hotel inspectors, then the assumption would be valid. It would be unlikely to be so for occasional hotel users. The output of a sample of Q-sort tests should be seen as evidence of a ``reliable schematic'' or a cognitive pattern (Thomas and Baas 1992). It plays the role of setting up empirical approaches so that theory can be tested (Kerlinger 1992). Essentially, Q-sort is about nding concepts and categories, which capture an entity, by nding stimuli that can be clustered to form a description of it. If people can describe it, then it may exist. It is a ``dimensionless'' task in which subjectivity and objectivity grope around to nd each other (Coxon and Jones 1978:65). The rationale for using Guttman procedure is the assumption of discrete dimensions, the evidence for which would be their unidimensionality. The study follows the line of Gerbing and Anderson (1988) and accepts that exploratory factor analysis is unsuitable for conrming unidimensionality. The two main properties of Guttman scaling are that it is simultaneously ordinal (hierarchical) and

206

HOTEL EVALUATION

cumulative. For example, salt, rock, and diamond can be ordered according to hierarchical order based on the degree of hardness. Furthermore, the structure of cumulation can be checked according to a predetermined criterion, which in this example is hardness. On a purely unidimensional scale, if a person accepts that salt is hard, they must accept that rock is harder. Therefore, in the Guttman procedure, unidimensionality is established by displaying both hierarchical and cumulative properties of the data (Guttman 1944; McIver and Carmines 1981; Oppenheim 1966). The application of Guttman utilized in the study uses a template in the form of an expected or ``ideal'' response category. Just as in the rock example, materials are also ranked by hardness; thus, in this study, responses are sequences set against a template and the degree of error is then computed. As to the study methods, the design consisted of a series of procedures, which ultimately led to a questionnaire incorporating the Guttman principle. These were the selection of dimensions and denitions from the literature; a Q-sort procedure for generating and validating item statements; and a sequencing procedure (equivalent to salt, rock, diamond) to establish rules for scaling. The resultant questionnaire was tested in a eld study. Selection of Dimensions for Testing There are two sources of dimension development, those formed conceptually through argument and those derived from factor analysis. These dimensions are, for the most part, set within models nroos 1984; Parasuraman, Zeithaml and Berry 1988) and are, (Gro therefore, constructed in multi-dimensional sets. Early work displayed a profusion of dimensions and a degree of duplication. This led to the remodeling of sets in which dimensions were composited into simpler models. Table 1 illustrates the range of dimensions found in the literature. Its matrix is a conguration of service quality dimensions taken from consumer behavior and hotel evaluation studies. It cross-references the dimensions found in hotel evaluative studies with those in generic service quality research to form a structural framework. The horizontal axis is taken from the model by Lehtinen, Ojasolo and Ojasolo (1996), which was itself derived from the composite model by Lehtinen and Lehtinen (1991). It categorizes dimensions according to two levels of abstraction: generic and specic. The vertical axis gives the frequency of occurrence of each dimension in hotel evaluation studies. This matrix was used in conjunction with a review of the hotel evaluation literature to nd dimensions, which would be worth testing. In the matrix, the hotel ones are cross-referenced against their nearest equivalent generic dimension. Where there was not an exact match, a process of conceptual alignment was used. For example, consistency is here part of the reliability dimension since Parasuraman et al (1985) argue that reliability is the consistency and dependability of service organization. If no match was possible,

EKINCI AND RILEY

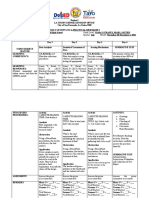

Table 1. Hotel Evaluation Matrixa

Studies in Hospitality Literature Physical Quality Acc Fick and Ritchie (1991) Farsad and LeBurto (1994) Nightingale (1985) Saleh and Ryan (1992) Clow, Garretson and Kurtz (1994) Lewis (1984a) Cadotte and Turgeon (1988) Lewis (1984b) Tan X X XX X X X XX X XX XXX X X X X X X X Interactive Quality Res Pro Staff Com Und Corporate Quality Rec Time Rel Ot Im Ass X

207

Unique

Empathy

X X

Expectation Price Service Q., Convenience, Quiet, Price, Process Value for money

Lockwood, Gummesson, Hubrecht and Senior (1992) Oberoi (1989) Haywood (1983) Barsky and Labach (1992)

X X X XX XX X XX XXX X XX 28

X X

X X

Maintainability Price, Service

Lewis and Owtram (1986) Knutson (1988) Moreno-Perez (1995) Total frequency

X X

X X 2 X 7 X 4

Price

a Acc: Accessibility, Tan: Tangibles, Res: Responsiveness, Pro: Professionalism, Staff: Staff behavior and attitude, Com: Communication, Und: Understanding, Rec: Recovery, Time: Timeliness, Rel: Reliability, Ot: Other Guests, Im: Image, Ass: Assurance, Unique: Unique dimensions.

the hotel evaluative dimensions were considered unique and listed on the right of the matrix. From Table 1, dimensions are extracted on the basis that they had been frequently used in connection with hotels using f 3 as the arbitrary entrance rule. According to the vertical axis, the six dimensions of tangibles f 28), accessibility f 8), staff behavior and attitude f 7), reliability f 3), image f 4), and assurance f 3 are the most frequently quoted ones for the evaluation of hotels. The literature suggested that the dimensions of assurance and image should combine to form ``output quality'' (Bitner, Booms and Tetrault 1990; Lehtinen and Lehtinen, 1991). With this adjustment, and with the inclusion of a nominated dimension called timeliness (Dawes and Rowley 1996; Taylor 1994), the study adopted for testing six service quality dimensions for evaluating hotels: physical quality (tangibles), accessibility, staff behavior and attitude, reliability, output quality, and timeliness. In adopting staff behavior as a dimension, the study followed the line of Moreno-Perez (1995)

208

HOTEL EVALUATION

who included professionalism within that dimension. The six dimensions then went into the Q-sort procedure. Q-sort and Sequencing Procedure At this stage the objective is to see if the six dimensions can be exclusively described and differentiated. The tasks of the Q-sort are to create denitions that capture the conceptual meaning of each dimension; to generate a bank of descriptive statements which ostensibly represent the dimensions; and to conduct experimental tests to ascertain whether the stimuli, generated in the latter procedure, can be matched against the conceptual denitions. This is a preliminary test of whether the six dimensions are valid as evaluative constructs. Their concepts were taken from the literature and the stimuli generated in accord with the denitions. For example, the following is the denition of staff behavior and attitude:

It is the hotel employees' degree of demonstrated competence in the performance of their tasks and the quality of empathy displayed in interaction with customers.

The initial set of stimuli were derived directly from the literature and revised by a senior hotel inspector and by the researchers. The denition of dimensions and the stimulus were rened until they were sufciently clear to be operational in a Q-sort test. The procedure started with 155 stimuli consisting of 31 ``sets of ve''. This set format was ordered from the most acceptable to least acceptable. In the rst procedure, 41 subjects (49% female, 51% male) were asked to associate the 155 statements arranged randomly on cards against six denitions and a ``don't know'' category. At this preliminary stage of the procedure, the selection of subjects was limited to two criteria; that they were over 20 years of age and that they had stayed in a hotel within the last 12 months. The rules of the procedure are that a denition only exists if the statements describe it and that at least 60% of the sample allocate the same descriptors to the denition (Hinkin and Schriesheim 1989). The logic which underpins this test is circular. Proof that a dimension exists is through nding stimuli, which describe them. The output of this stage was that of the original 155 statements, 35 were found to represent the six dimensions under the rules. This meant that each of the dimensions had ve statements assigned to them as descriptors. The dimension of physical quality was the exception in that it had two sets of ve statements. At this juncture, the product of the Q-sort has to be integrated with the scaling principle which underpins the nal questionnaire. This principle links unidimensionality, (the measurement of a single dimension) to the actual task of evaluation. This is achieved through a sequencing procedure. This format, based on the Guttman principle of most to least acceptable, maintains the principle of unidimensionality. But it uses a template, which orders items along a single dimension with a criterion that has most and

EKINCI AND RILEY

209

least acceptable poles (at the Q-sort stage, the sorting was on the basis of most favorable to least favorable). Edwards denes this as a psychological continuum of the measured dimension, which is believed to exist (1957:19). In the previous analogy, hardness was the dimension which enabled a set of materials to be sequenced. In this study, each of the six dimensions is hypothesized to play the role of hardness. The main difference is that the template is both hierarchical cumulatively horizontal. To apply the results of the Q-sort to a sequencing procedure, the study used a different set of subjects from the rst stage of the procedure. The new sample consisted of 40 subjects (50% female, 50% male) and a control sample of 25 professional hotel inspectors from a national motoring organization. Each subject was asked to rank each of the ``set of ve'' statements, which passed the Q-sort, test into an order from most acceptable (1) to least acceptable (5). Table 2, as an example, consists of ve statements intended to represent the physical quality dimension. As a result of the sequencing procedure, the statements in Table 2 have been ordered as shown by their rank number. A consensus was approved by application of the Q-sort rules. No signicant difference was found between the two samples (both were above 70% agreement with the template). The items were then transferred, in random order, to the main survey. If the items had not passed this sequencing test the later use of Guttman scaling would not be possible, because the basis of the psychological task is to recapture the sequences. Main Survey Design and Sample The main survey was conducted by a questionnaire containing all 35 questions derived from the previous procedures. Table 3 shows the dimensions of its statements. The questions were randomized and subjects were asked to respond in terms of ``yes'' or ``no'' to how they felt about the hotel they had just stayed in. The design principle is simply that the dimension would be validated if the responses to the randomized order were in line with the seven templates. By way of illustration, Table 4 (based on Table 2) shows one ``ideal'' and one error response on the ve questions. Response pattern 1 is correct because there are no contradictions in the

Table 2. The Order of Statements Representing Physical Quality Dimension

Statements Degree of Evaluation Most acceptable Acceptable Neutral Unacceptable Least acceptable Rank Order in Pilot Study 1 2 3 4 5

The The The The The

hotel was clean and tidy hotel was clean but a bit messy cleanliness of the hotel was just about tolerable hotel did not seem to have been cleaned properly hotel was dirty and unhygienic

210

HOTEL EVALUATION

Table 3. The Sequence of Statementsa

Number

Dimensions and Scales

Physical Quality: Scale I 1 The decor was beautifully coordinated with a great attention to detail and clear vision 2 Some thought had gone into the decor, it had an obvious style 3 There was some style in the decor, but it was not beautiful 4 The decor was let down by lack of thought and lack of style 5 The decor was a tasteless jumble Physical Quality: Scale II 6 The hotel was clean and tidy 7 The hotel was clean but a bit messy 8 The hotel cleanliness was just about tolerable 9 The hotel did not seem to be cleaned properly 10 The hotel was dirty and unhygienic Staff Behavior and Attitude 11 Staff were really good, they displayed effortless expertise 12 Staff were competent and had obviously received some training 13 Staff competence tended to breakdown when under pressure 14 Staff were not very competent and had not been trained properly 15 Staff were incompetent and did not know what they were doing Output Quality 16 The whole experience of the hotel was exceptionally good, simply wonderful 17 I think the whole experience in the hotel was just better than I expected 18 The hotel was OK and pretty typical of its type 19 The hotel did not make any impression on me 20 I did not like the hotel at all Accessibility 21 It was very easy to nd your way around the hotel 22 If you looked around there were directions and information to help you nd things 23 You had to search hard for directions and information to nd things 24 You searched without success for information and direction 25 It was impossible to nd your way around the hotel because it was a complete maze Timeliness 26 The meal service was well timed and efcient 27 The meal service was quite punctual 28 The speed of meal service was adequate 29 The meal service was much slower than I expected 30 The meal service was too slow to endure Reliability 31 The hotel always delivered exactly what it promised 32 The hotel delivered on most of its promised services exactly but some were minimal 33 The hotel supplied the promised services, but it was only minimum requirement 34 Although promised, services provided were minimal, even following my persistent request 35 The hotel did not deliver any of its promises The statements shown are listed in ``template sequence''. In the questionnaire they were presented in random order. Respondents were asked to rate each item either ``yes'' or ``no''.

a

EKINCI AND RILEY

211

Table 4. The Statements of Physical Quality Dimensions and the Score Pattern

Statements The hotel was clean and tidy The hotel was clean but a bit messy The cleanliness of the hotel was just about tolerable The hotel did not seem to have been cleaned properly The hotel was dirty and unhygienic

Degree of Evaluation Most acceptable Acceptable Neutral Unacceptable Least acceptable

Rank Order in Pilot Study 1 2 3 4 5

Response Pattern 1 no no no yes yes

Response Pattern 2 no yes yes yes yes

sequence. It is unambiguously negative. By contrast, response pattern 2 displays a contradiction in that saying ``yes'' to the item ``the hotel was clean but a bit messy'' goes against the remaining three negative statements. Following this example, the principle that guides the analysis is that for each dimension there is a template ``hidden'' within the randomization. The test of unidimensionality is whether subjects in the main sample answer questions in line with the templates. This requires a statistical rule to judge the acceptable degree of deviation from ``perfect'' template responses. The nature of this rule is ``error assessment''. The principle involved is that the performance of each scale item is compared with an ideal or optimal cumulative scale. Through this comparison the number of errors (or the number of times the cumulative scale of the item diverges from the ideal template) can be calculated. Guttman (1950) set the standard of 10% error as the maximum; thus, an item needs a coefcient of reproducibility (CR) of 90%. By a successive process of elimination the output is a set of items (or a scale) that reaches the 90% level. The CR value has two important properties. First, it is used as an indicator of unidimensionality. Second, it is an indicator of reproducibility or reliability. Therefore, according to Guttman, if a scale has a unidimensional structure while producing up to 10% error, it is reliable. This property of the measure is slightly different from the Cronbach's Alpha which does indicate internal scale consistency or reliability but does not indicate unidimensionality or any form of internal or external validity (Gerbing and Anderson 1988). It is worth noting the contrast between the use of Likert and Guttman scaling. With the former, reliability is assessed by the homogeneity of scale items (usually tested by linear correlation) and error is computed through summation across the total sample. By contrast, Guttman computes error for each individual on the basis of the hierarchical and cumulative structure of the scale (or unidimension-

212

HOTEL EVALUATION

ality) (Edwards 1957). Here, a scale is valid, internally consistent or reliable if 90% (CR value) of the sample provides this structure. In this study, the reliability (indirectly, reliability of dimensions) is also examined by looking at the stability of scales in two different samples: the sample used for the Q-sort tests and the main questionnaire sample. In contrast to exploratory studies, where the intention is to identify a dimension, here the dimensions are known and their validity is established through the Q-sort study. Hence, in the main sample, the same structure is expected in order to substantiate their reliability. With reference to Table 4, the physical quality dimension is scaled with the ve items along a single continuum ranging from positive to negative evaluation. The data analyzing process involves checking the respondent score against the perfect scale. Subject one displays an unfavorable response pattern; therefore, no error is produced. In substantive terms, it is also possible to interpret the response pattern in terms of whether the subject is positive, neutral, or negative. The principle of Guttman is applied in the two cumulative stages. The rst stage involves whether respondents discriminate the scale properly against the perfect template. For example, subject two in Table 4 made an error since this evaluation is contradictory. This respondent thinks that the hotel is clean and dirty at the same time. This produces an error in the scoring. The scoring procedure has itself two main components: its error count against the perfect scale and the direction of the score on a positivenegative continuum. The components produce combinations which are, on the positive side , , and for the negative side , , with as a neutral pattern. If a scale qualied in the rst stage, it is transferred to the next stage. In the second stage, unidimensionality of the scale is tested within the two samples. In the positive sample, dened by the scale's two positive items, the perfect scale pattern contains three possible response patterns , , . This means that a subject does or does not endorse both items. In this respect, the subject may endorse only the less favorable item. If, however, the subject endorses the most favorable item, which is the extreme item of the scale, it is expected that the other favorable item is also endorsed. If not, this is an error . The same analysis is valid for the negative sample where the perfect scale pattern would be , , and the error . Both samples should produce a unidimensional structure in order to validate the dimensions. In order to meet predictive validity criteria, the study incorporated questions to test whether the dimensions predicted behavior intentions. The questions were ``Would you return to this hotel?'' and ``Would you recommend this hotel to your friends?'' The survey was conducted by a questionnaire on a sample of hotel users. Randomization of the sample was achieved through using, as a basis of distribution, the reservation system operated by the largest motoring organization in the United Kingdom. A total

EKINCI AND RILEY

213

of 600 questionnaires were sent out to subjects who telephoned the reservation service. This method ensured a geographical spread across the country. A response of 255 was achieved (43%). The questionnaire itself contained a number of demographic and categorical variables. The gender distribution was 47% female, 53% male. Other variables measured included age, purpose of travel, income, frequency of hotel usage, and hotel class. Study Findings The outcome of this research is to verify the unidimensionality of the nominated dimensions in two stages. This is secured, under the technique adopted, by an error count of less than 10% (or a CR value of over 90%). Stage 1. Table 2 contains the actual questions and displays how they were sequenced by the sample from most acceptable to least acceptable. The error count for each of the six nominated dimensions is also shown. The far right column of Table 5 shows that, at this stage, each dimension has qualied. However, when demographic and categorical variables were applied to this table, one of the dimensions dropped out. These variables consisted of age (ve categories), income level (four categories), purpose of travel (leisure or business), and frequency of stay (four categories). Further analysis revealed that in two categoriespurpose of travel CR 0:74 in leisure class, n 31 and frequent hotel users (in two groups of this category CR 0:79, n 24, and CR 0:63, n 22)the dimension of reliability showed too much diversity and failed to meet the minimum CR value. As this error was not random but biased to these categories, the reliability dimension, which comes from SERVQUAL, is rejected as a valid dimension. Stage 2. At this juncture, the respondents are segmented into positive, negative, and neutral categories. The unidimensionality of

Table 5. Dimensions and Error Count n 255)

Dimensions The Content of the Scale The Order of the Statements from Positive to Negative Evaluation Most Acceptable Physical quality 1 Physical quality 2 Staff behavior Output quality Accessibility Timeliness Reliability Decor Cleanliness Competence of the staff Overall experience Accessibility of hotel facilities Speed of service Keeping promises Q1 Q6 Q11 Q16 Q21 Q26 Q31 Acceptable Neutral Unacceptable Least Acceptable Q5 Q10 Q15 Q20 Q25 Q30 Q35 17 17 9 23 9 24 0.93 0.93 0.96 0.90 0.96 100 0.90 Error in Sample CR

Q2 Q7 Q12 Q17 Q22 Q27 Q32

Q3 Q8 Q13 Q18 Q23 Q28 Q33

Q4 Q9 Q14 Q19 Q24 Q29 Q34

214

HOTEL EVALUATION

each scale is then checked by using the GoodenoughEdwards error counting technique in both samples (McIver and Carmines 1981). A major criticism of the Guttman scale is that high CR values can be obtained by items not discriminating on each pole (McIver and Carmines 1981:50). In other words, differences among most favorable are lost. Minimal marginal reproducibility and coefcient of scalability are two criteria used to check the internal consistency of the structure of the scale. The former score should not be excessively high, or at least should be less than CR. Similarly, the coefcient of signicance should be greater than 0:60 if a scale has a balanced structure (Dunn-Rankin 1983). Table 6 compares the three measures of the scale across two samples. These samples consist of those subjects who rated the hotels in positive terms and those who gave a negative evaluation. It has been pointed out that the form of error counting differs between stages 1 and 2 and it is for this reason that the CR values in Table 6 will be different from those in Table 5. The analysis in Table 6 suggests that only physical quality 1, staff behaviorattitude, and output quality have qualied across the three criteria. However, the problems related to physical quality 2 may be accounted for by the use of double-barreled terminology. While accessibility and timeliness produce high CR scores, the unidimensional structure of these scales is not supported by minimal marginal reproducibility and coefcient of scalability scores. The dimension of reliability was eliminated at the error assessment stage because it showed bias in certain categories. However, this was re-checked in the positivenegative samples where again it failed to reach the required CR value of 0.90. CR score for the reliability dimension in the positive sample is 0.37 n 207), in the negative sample is 0.83 n 12).

Table 6. Three Measures of the Scale Across Two Samplesa

Dimensions (n ) Physical Q1, decor Physical Q2, cleanliness Staff behav./attitude Output quality Accessibility Timeliness 185 222 224 120 224 199

Positive Sample CR 0.98 0.19 0.98 0.93 0.94 0.98 MMR 0.70 0.52 0.86 0.74 0.93 0.97 CS 0.93 0.92 0.75 0.73 0.14 0.33 (n ) 22 7 16 45 12 21

Negative Sample CR 0.95 0.86 100 0.91 100 100 MMR 0.75 0.64 0.81 0.55 0.96 0.73 CS 0.80 0.61 1 0.80 1 1

a CR: coefcient of reproducibility; MMR: minimal marginal reproducibility; and CS: coefcient of scalability.

EKINCI AND RILEY

215

External Validity With support for three of the initial six dimensions, the next stage was to ascertain if the three dimensions could predict the behavioral intentions specied in the questionnaire. A logistic regression procedure was conducted on the dimensions to see if they predict ``return'' and ``recommend'' behavior (Norusis 1993). As this procedure is based on the validated sample those subjects who produced errors in the rst stage are eliminated. This procedure was different for each dimension and the numbers subtracted from 255 are shown in the ``error in sample'' column of Table 5. As the questionnaire was originally scored on the basis of ``yesno'' response pattern, each subject on each dimension was rescored along the most acceptableleast acceptable continuum (such as 2 1 0 1 2). By this means, a single score per subject and then overall score per dimension was obtained. For instance, if a subject's response pattern is `` '', the score for this will be 1.5 2 1 0 0 0 3=2 1:5). Table 7 shows the results of the logit estimation based on the maximum-likelihood method corresponding to the three scales. The two logit models based on the two behavioral variables indicate a reasonably good t between both variables and the ve scales by chi square and model improvement statistics p < 0:000). Measured in terms of classication rate (or the agreement degree between the direction of the behavioral variable and that of the dimension variable), there is a reasonably good t. The overall classication rate is, for ``intention to return'', 81% (44% for non-return and 91% for return to hotel). The rate for ``intention to recommend'' is 84% (52% for non-recommend and 92% for recommend). In other words, there was a good t between intentions and positive and negative evaluations on the dimensions. Both variables (64 and 65%, respectively) exceeded the rate of proportional chance criterion (Morrison 1969), which indicates a discriminating power. However, the rate of 44% for the ``non-return'' group is of some cause for concern for Model 1. The implication is that valid service quality dimensions

Table 7. Logistic Regression Analysis Dimensions

Dimensions

Intention to Return

Intention to Recommend Sig.

Coeff. Wald statis. Sig. Coeff. Wald statis. Physical quality 1 0.32 1.31 Staff behavior 0.16 0.20 Output quality 1.41 25.22 Constant 0.78 3.24 Model 1: Model chi-square sig.: 0.000 (3 d.f.) Improvement sig.: 0.000 (56.94, 3 d.f.) Correct classication rate: 81.2% 0.25 0.64 0.00 0.08

0.26 0.88 0.34 0.46 1.43 0.23 1.38 22.59 0.00 0.23 0.23 0.62 Model 2: Model chi-square sig.: 0.000 (3 d.f.) Improvement sig.: 0.000 (62.25, 3 d.f.) Correct classication rate: 84.0%

216

HOTEL EVALUATION

can exist without any connection to the ``intention to return'' variable. While this does not invalidate the logit model, it does reduce its predictive power. But two arguments offer explanation. These are, one, whatever the assessment of quality, people may have other non-evaluative motives (such as the desire for a change) for not returning and, two the claim for the power of evaluative dimensions is only that they give direction to behavioral intentions. It is clear from Table 7, that not all of the variables are signicant in predicting the respondents' behavioral intention. Only output quality has predictive power between the choices of ``return and non-return to the hotel'' p < 0:000). Further analysis on output quality reveals that it is correlated with physical quality and staff behavior and attitude (0.62 and 0.57, respectively) and in addition that these two dimensions are themselves correlated (0.52). Taking these intercorrelations into account, it can be inferred that output quality is operating at a different level of abstraction. Although it was beyond the study's remit, when output quality was removed and a further logistic regression applied, the remaining dimensions were signicant. This proves that they had predictive value. The ``intention to return'' model also tted well (model chi square: 34, p 0:00, improvement: 34.0, p 0:00, 82% correctly classied, staff behavior and attitude: Wald statistics 6:05, beta 0:66, p < 0:01, physical quality: Wald statistics 11:8, beta 0:75, p 0:00, constant: Wald statistics 0:17, beta 0:14, p 0:68 and the intention to recommend model displays a good t (model chi square: 47.9, p 0:00, improvement: 47.9, p 0:00, 84% correctly classied, staff behavior and attitude: Wald statistics 12:0, beta 1:12, p < 0:001), physical quality: Wald statistics 11:5, beta 0:77, p < 0:001, constant: Wald statistics 1:58, beta 0:54, p 0:20). This may support the argument that output quality operates at a different level of abstraction in that it has connections to the other dimensions, but is the only one to have predictive power. In the nal stage, the discriminant validity of the scales was also checked by paired sample t-test. This analysis suggested that the mean scores of dimensions were statistically different p < 0:00). CONCLUSION One possible view of the literature of service quality measurement is that although it demonstrates considerable progress it still contains all the conceptual and methodological problems it started with. This study does not change that position. But if the establishment of reliable constructs enhances the security of the concepts involved in the measurement of quality, then the study has made a small contribution to this literature. The previous empirical thrust has been consistently along the lines of probabilistic measurement, but it is suggested here that alternative ways of tackling measurement would be fruitful. In methodological terms, the study attempts to show the merits of using two techniques that are not often applied and rarely used

EKINCI AND RILEY

217

in tandem. The suggestion has been that they are an alternative approach to the more commonly used Likert scaling procedure. In terms of the existing empirical literature, the combination of Q-sort technique and Guttman scaling is an alternative way of establishing unidimensionality. Although Likert scaling allows for more extensive analysis for modeling dimensions, if the task is going after hypothesized single traits, as in the study described, then the main advantage of Guttman is that it has two parameters in establishing a unidimensional scale. The scale is hierarchical and cumulative. This means that respondents are grouped according to scale items and items grouped according to respondents, whereas only respondents are grouped according to scale items in the Likert scaling (McIver and Carmines 1981:87). If the task is conrmatory, then the deterministic character of Guttman is more appropriate than the probabilistic nature of Likert. The principal contribution of the study to methodological approaches lies in its emphasis on content validity as the basis for scale construction and in seeing the establishment of construct validity in terms of a total process, rather than as an outcome of statistical ndings (Peter 1981). By means of Q-sort technique face validity and, to a degree, content validity of the scales is developed at the initial stage and is not entirely reliant upon statistical ndings. The study has attempted to establish reliability and construct validity by adopting a procedure that builds such properties into the scaling process itself. This approach was adopted because content validity was a critical issue in the literature of service quality measurement (Buttle 1996). Furthermore, a contribution is made by adopting the premise that the whole process can be designed without postulating a model with implications of relationships among dimensions. By this means the focus of achieving construct validity through unidimensionality was maintained. It is this design that explains the absence of exploratory factor analysis. One of the key limitations of the study was that no causal relationship was assumed. The search was for single independent dimensions. Therefore, although conrmatory factor analysis is still possible, it was not undertaken because of the limits set by the study's assumptions. Further research could model these validated dimensions. Although the primary focus of this study has been methodological, it is important to place its empirical ndings in relation to the methodology used, to other empirical work, and to the theoretical context. In this respect the discussion will concentrate on what are possibly its two most signicant ndings: that single dimensions are shown to have the capability of acting independently and the emergence of output quality as possibly a super-ordinate dimension. The empirical purpose of the study was to attempt to validate a number of evaluative dimensions taken from earlier empirical and conceptual studies. The ndings, in part, offer support to earlier empirical studies and generic service quality models in that they validate some of the dimensions. However, those validated by other studies were not replicated here. Of the two dimensions taken from

218

HOTEL EVALUATION

SERVQUAL, only one was substantiated. The reason may be that this scale is specic to retail environment. For future research, it is worth noting here that the dimension of staff attitude and behavior, which, does not appear in other studies, was validated. Perhaps the most interesting nding of the study is the emergence of the dimension of output quality. In the literature this dimension was conceived as a composite of image, assurance, and benets. In some respects, this dimension is the closest to the one concept left out of the study questionnaire: that of overall quality. However, a dimension of output quality is, in fact, not the equivalent of a question on overall quality. By going directly from dimensions to behavioral validity, it was attempted to strengthen the case for arguing the power of the dimensions themselves to discriminate behavior. This position is consistent with the notion that an overall perspective on quality can best be constructed through the converging structure of valid dimensions rather than by a single expression which is supported by the ndings. Output quality has a character, which is both appreciative, in the sense of ``I like it'' and calculative, in the sense of ``it gives me what I want''. This dual character is suggestive of the model of service nroos (1984). His conceptualization emphaquality devised by Gro sizes what people get and how they get it as a functional process. There is also a suggestion that the image of the organization (hotel in this case) is being evoked, which is in line with the same model. However, what is important to the general debate is that output quality was found to have predictive power when correlated with valid dimensions not so empowered. This is both suggestive of a super-ordinate dimension and is in line with simple compensatory models, which assume that dimensions work independently without any compensatory trade-off (Hawkins, Best and Coney 1983). Given these ndings, it might be appropriate to put them in the perspective of the debate on the nature of what constitutes a generic dimension. Having adopted the genericspecic dichotomy, the literature has invited a number of problems, including what ``generic'' means in the realm of perception and evaluation; whether it is a question of recognizing similarity between attributes that occur across a range of service contexts; whether it is a matter of superordinate dimensions which hover above attributes; and if so, whether they are discrete or the product of accumulated sub-ordinate dimensions. By contrast, it is important to ask if the term ``specic'' is a discontinuity of perceptual categorization and/or the uniqueness of attributes to a context. To add to this complexity is the issue of levels of abstraction which implies that the above questions can all be answered in the afrmative at different levels of abstraction. For the most part, the empirical response to these issues has been to nd and validate dimensions and to interpret the level of abstraction through the correctional relationships between the dimensions. If a generic dimension is found to be valid in different situations or, found to be super-ordinate to dimensions which are dened by

EKINCI AND RILEY

219

attributes of the product or service, then it is also appropriate to ask how the dimension of output quality can be interpreted. The rst criterion was not an issue in the research design and thus it is inapplicable. But by the second criterion, output quality might be a contender. What is important, however, is that when measured in a strictly dened context, a dimension without a specic character emerges. It may well be that whatever dimensions are ``in action'' in a particular context, being generic or specic, they may be more likely to be validated in a specic context because the descriptors, which form the basis of the scale, are context specic. Thus, in the case where scaling is to a specic context, failure to nd a dimension does not infer that it does not exist at all but merely that it is not valid, and by implication not scalable. Therefore, a failure to nd a dimension, which happens to be generic, does not mean it does not exist and cannot be used in other situations. The situation could have inuenced the outcome. This possibility was a limitation of the study. To add a different perspective, it is interesting and salient to the debate on genericspecic dimensions, to consider the way these issues are seen by cognitive science. Cognitive studies based on Personal Construct Theory, for example, have shown that grids tend to be purpose specic but are capable of sharing dimensions with other schema when it is appropriate. In the perception and categorization literature dimensions which appear in different schema, are not, as in market research and the quality literature, denoted as generic. They are simply what they are: just another dimension of a particular schema. In other words, dimensions are seen as portable across specic contexts. A complementary picture of the complexity of levels of abstraction emerges if it is seen as a process of perceptual categorization. Here dimensions are seen as part of group categorization processes. The rationale for this is that those evaluative criteria follow perceptual categorization and that there are such things as pre-evaluated categories of which stereotypes would be examples (Tajfel 1978). Further, categorization is a grouping process but one which transforms differences into similarities and vice versa. In this light, it is possible to see levels of abstraction as part of the categorization process, taking the form of levels of inclusiveness of categories, inclusionexclusion from a category, and degree of prototypicality within a category. The organizing principles would be either similarity and difference or meta-contrast, the difference between differences (Oakes, Haslam and Turner 1998). For example, a person in a budget hotel might be judging it from one perspective within a set of group categories of ever decreasing inclusiveness such as service operations in general hotels or budget hotels. If the person was indeed using budget hotels, then comparisons may be between this category and some other groups of hotels such as four-star or, it may be between the object hotel and the person's prototypical example of a budget hotel. To make matters more complicated, dimensions are not necessarily specic to cat-

220

HOTEL EVALUATION

egories and the person may bring concepts to the judgment of the hotel dimensions, which are larger than the category the hotel is placed in. The key assumption in all this is that the evaluation depends on where the object is psychologically ``placed''. There is no contradiction here between the notion of generic dimensions and categorization if the former are seen as portable across categories. However, in reviewing the literature on service quality, Ekinci and Riley (1998) make the suggestion that if there are to be advances in the measurement of service quality, bridges need to be made which link back to the cognitive literature so that some of the techniques therein can be applied.&

Acknowledgments This research was made possible by grants from Adnan Menderes University.

REFERENCES

Babakus, E., and W. G. Mongold 1992 Adapting the SERVQUAL Scale to Hospital Services: An Empirical Investigation. Health Services Research 26:767786. Barsky, J. D., and R. Labach 1992 A Strategy for Customer Satisfaction. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 33(5):3240. Bitner, M. J., B. H. Booms, and M. S. Tetrault 1990 The Service Encounter: Diagnosing Favorable and Unfavorable Incidents. Journal of Marketing 54(2):7184. Buttle, F. 1996 SERVQUAL: Review, Critique, Research Agenda. European Journal of Marketing 30:832. Cadotte, E. R., and N. Turgeon 1988 Key Factors in Guest Satisfaction. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 28(4):4551. Carmen, J. M. 1990 Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality: An Assessment of The SERVQUAL Dimensions. Journal of Retailing 66:3355. Clow, K. E., J. A. Garretson, and D. L. Kurtz 1994 An Exploratory Study into the Purchase Decision Process Used by Leisure Travelers in Hotel Selection. Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing 2(4):5372. Coxon, A. P., and C. L. Jones 1978 The Images of Occupational Prestige. London: Macmillan. Cronin, J. J. Jr., and S. A. Taylor 1992 SERVPERF versus SERVQUAL: Reconciling Performance-Based and Perception-minus-Expectations Measurement of Service Quality. Journal of Marketing 58(3):15131. Dawes, J., and J. Rowley 1996 The Waiting Experience: Towards Service Quality in the Leisure Industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 8(1):1621. DeVellis, R. F. 1991 Scale Development: Theory and Applications. London: Sage. Dunn-Rankin, P. 1983 Scaling Methods. New Jersey: Hillsdale. Edwards, A. L. 1957 Techniques of Attitude Scale Construction. New York: Appleton-CenturyCrofts. Ekinci, Y., and M. Riley 1998 A Critique of the Issues and Theoretical Assumptions in Service Quality

EKINCI AND RILEY

221

Measurement in the Lodging Industry: Time to Move the Goal-Posts? International Journal of Hospitality Management 17:349362. Farsad, B., and S. LeBurto 1994 Managing Quality in the Hospitality Industry. Hospitality Tourism Education 6(2):4249. Fick, G. R., and J. R. B. Ritchie 1991 Measuring Service Quality in the Travel and Tourism Industry. Journal of Travel Research 30(2):29. Finn, D. W., and C. W. Lamb 1991 An Evaluation of the SERVQUAL Scales in a Retailing Setting. Advances in Consumer Research 18:483490. Gerbing, D. W., and J. C. Anderson 1988 An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and its Assessment. Journal of Marketing Research 15:186192. nroos, C. Gro 1984 A Service Quality Model and its Marketing Implications. European Journal of Marketing 18(4):3644. Guttman, L. 1944 A Technique for Scale Analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement 4:179190. 1950 The Basis for Scalogram Analysis. In Measurement and Prediction, S. A. Stouffer, L. Guttman, E. A. Suchman, P. F. Lazarsfeld, S. A. Star and J. A. Claussen, eds., pp. 6090. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Hattie, J. 1985 Methodology Review: Assessing Unidimensionality of Tests and Terms. Applied Psychological Measurement 9(2):139164. Hawkins, D. L., R. J. Roger, and K. A. Coney 1983 Consumer Behavior: Implications for Marketing Strategy. Texas: Business Publications. Haywood, K. M. 1983 Assessing the Quality of Hospitality Services. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2:165177. Hinkin, T. R., and C. A. Schriesheim 1989 Development and Application of New Scales to Measure the French and Raven (1959) Bases of Social Power. Journal of Applied Psychology 74:561 567. Kelly, G. A. 1955 The Psychology of Personal Constructs. New York: Norton. Kerlinger, F. 1992 Foundations of Behavioral Research. New York: Harcourt Brace Collage. Knutson, B. 1988 Ten Laws of Customer Satisfaction. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 29(3):1417. Lehtinen, U., and J. R. Lehtinen 1991 Two Approaches to Service Quality Dimensions. The Service Industries Journal 11:287303. Lehtinen, U., J. Ojasalo, and K. Ojasolo 1996 On Service Quality Models, Service Quality Dimensions and Customer's Perceptions. In Managing Service Quality, P. Kunst and J. Lemmink, eds., pp. 109115. London: Paul Clapman. Lewis, B., and B. Owtram 1986 Customer Satisfaction with the Package Holidays. In Are They Being Served?, B. Moores, ed., pp. 201213. Oxford: Philip Allan. Lewis, R. C. 1984a Getting the Most from Marketing Research III: The Basis of Hotel Selection. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 25(1):5469. 1984b Getting the Most from Marketing Research IV: Isolating Differences in Hotel Attributes. The Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 25(3):6477.

222

HOTEL EVALUATION

Lockwood, A., E. Gummesson, J. Hubrecht, and M. Senior 1992 Developing and Maintaining a Strategy for Service Quality. In International Hospitality Management Corporate Strategy in Practice, R. Teare and M. D. Olsen, eds., pp. 312339. London: Pitman. McIver, J. P., and E. G. Carmines 1981 Unidimensional Scaling: Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. London: Sage. Mels, G., C. Boshoff, and D. Nel 1997 The Dimensions of Service Quality: The Original European Perspective Revisited. The Service Industries Journal 17:173189. Moreno-Perez, R. J. 1995 Service Quality and its Importance: A Study of Critical Incidents. M.Sc. dissertation in Hospitality Management, University of Surrey. Morrison, D. G. 1969 On the Interpretation of Discriminant Analysis. Journal of Marketing Research 6:156163. Nightingale, M. 1985 The Hospitality Industry: Dening Quality for a Quality Assurance Program: A Study of Perception. The Service Industries Journal 5:922. Norusis, M. J. 1993 SPSS for Windows: Advanced Statistics Release 6.0. Chicago: SPSS. Oakes, P., S. A. Haslam, and J. C. Turner 1998 The Role of Prototypicality in Group Inuence and Cohesion: Contextual Variation and the Graded Structure of Social Categories. In Social Identity: International Perspectives, S. Worchel, F. P. Morales, J. F. Paez and D. Deschamps, eds., pp. 7592. London: Sage. Oberoi, U. 1989 Quality Assessment of a Service Product: An Empirically Based Study of UK Conference Hotels. Ph.D. dissertation in Hospitality Management, University of Bournemouth. Oh, H., and S. Parks 1997 Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality Critical Review of the Literature and Research Implications for the Hospitality Industry. Hospitality Research Journal 20(3):3564. Oppenheim, A. N. 1966 Questionnaire Design and Attitude Measurement. London: Heinemann. Parasuraman, A., V. A. Zeithaml, and L. L. Berry 1985 A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its Implications for Future Research. Journal of Marketing 49(4):4150. 1988 SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perception of Service Quality. Journal of Retailing 64:1340. Parasuraman, A., L. L. Berry, and V. A. Zeithaml 1991 Renement and Reassessment of the SERVQUAL Scale. Journal of Retailing 67:421450. Parasuraman, A., V. A. Zeithaml, and L. L. Berry 1994 Alternative Scales for Measuring Service Quality: A Comparative Assessment Based on Psychometric and Diagnostic Criteria. Journal of Retailing 70(3):193199. Peter, P. 1981 Construct Validity: A Review of Basic Issues and Marketing Practices. Journal of Marketing Research 18:133145. Saleh, F., and C. Ryan 1991 Analyzing Service Quality in the Hospitality Industry Using the SERVQUAL Model. The Service Industries Journal 11(3):324343. 1992 Client Perception of Hotels: A Multi-Attribute Approach. Tourism Management 13:163168. Stephenson, W. 1953 The Study of Behavior. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Tajfel, H. 1978 Differential between Social Groups. New York: Academic Press.

EKINCI AND RILEY

223

Taylor, S. 1994 Waiting for Service: The Relationship Between Delays and Evaluations of Service. Journal of Marketing 58(2):5669. Thomas, D. B., and L. R. Baas 1992 The Issue of Generalization in Q-Methodology: Reliable Schematics Revisited. Operand Subjectivity 16(1):1836. Tractinsky, N., and S. Jarvenpaa 1995 Information Systems Design Decisions in a Global Versus Domestic Context. Management Information Systems Quarterly 507534. Vogt, C. A., and D. R. Fesenmaier 1995 Tourist and Retailers' Perception of Services. Annals of Tourism Research 22:763780. Submitted 18 August 1998. Resubmitted 15 November 1998. Resubmitted 11 February 1999. Resubmitted 29 July 1999. Accepted 1 November 1999. Final version 14 February 2000. Refereed anonymously. Coordinating Editor: Juergen Gnoth

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Yuksel 2003 - Writing Publishable PapersДокумент10 страницYuksel 2003 - Writing Publishable PapersRafael Pantarolo VazОценок пока нет

- 3.2 Darbellay and Stock 2012 - Tourism As A Complex Interdisciplinary ResearchДокумент18 страниц3.2 Darbellay and Stock 2012 - Tourism As A Complex Interdisciplinary ResearchRafael Pantarolo VazОценок пока нет

- (RN) Decrop 1999 - Triangulation in Qualitative Tourism ResearchДокумент5 страниц(RN) Decrop 1999 - Triangulation in Qualitative Tourism ResearchRafael Pantarolo Vaz100% (1)

- 4.3 Tribe 2006 - The Truth About TourismДокумент22 страницы4.3 Tribe 2006 - The Truth About TourismRafael Pantarolo VazОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Mini Lecture and Activity Sheets in English For Academic and Professional Purposes Quarter 4, Week 5Документ11 страницMini Lecture and Activity Sheets in English For Academic and Professional Purposes Quarter 4, Week 5EllaОценок пока нет

- Development of Assessment ToolДокумент21 страницаDevelopment of Assessment ToolJudy CoñejosОценок пока нет

- Fernandez Dufey Kramp 2011Документ8 страницFernandez Dufey Kramp 2011Valerie Walker LagosОценок пока нет

- Organizational Diagnostic ModelsДокумент36 страницOrganizational Diagnostic ModelsSHRAVANI MEGHAVATHОценок пока нет

- PR2 November 28-Dec 2Документ3 страницыPR2 November 28-Dec 2Edrin Roy Cachero SyОценок пока нет

- Quality of Life at Green and Non-Green CampusДокумент7 страницQuality of Life at Green and Non-Green CampusGamal HmrswОценок пока нет

- Should I Stay or Should I Go Understanding EmployeesДокумент30 страницShould I Stay or Should I Go Understanding Employeesarthasiri.udaОценок пока нет

- Multidimensional Sexual Approach QuestionnaireДокумент9 страницMultidimensional Sexual Approach QuestionnairePKhAndily Aprilia RahmawatiОценок пока нет

- Chapter1 5revisedДокумент59 страницChapter1 5revisedKrystal Lacson0% (1)

- The Case of Schools in Sidama Zone, EthiopiaДокумент9 страницThe Case of Schools in Sidama Zone, EthiopiaEshetu MandefroОценок пока нет

- Marketing Scales Handbook - Multi-Item Measures For Consumer Insight Research. Volume 7 (PDFDrive)Документ425 страницMarketing Scales Handbook - Multi-Item Measures For Consumer Insight Research. Volume 7 (PDFDrive)Tomy Fitrio100% (1)

- Impact of Western CultureДокумент27 страницImpact of Western CultureShruti VikramОценок пока нет

- Project Report Reliance FreshДокумент32 страницыProject Report Reliance FreshNilesh Sorde75% (4)

- Customer SatisfactionДокумент14 страницCustomer SatisfactionPrem Raj AdhikariОценок пока нет

- Sample PaperДокумент14 страницSample PaperAbu SufyanОценок пока нет

- JCEM Doloi 2013: October 2013Документ14 страницJCEM Doloi 2013: October 2013Tolu BoltonОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S1054139X14001645 MainДокумент8 страниц1 s2.0 S1054139X14001645 MainIsnandar PurnomoОценок пока нет

- BEDEWY D GABRIEL A Examining Perceptions of AcademДокумент10 страницBEDEWY D GABRIEL A Examining Perceptions of AcademLoredanaLola93Оценок пока нет

- Research Data Collection Methods and Tools: Presented by Likhila AbrahamДокумент50 страницResearch Data Collection Methods and Tools: Presented by Likhila AbrahamchetankumarbhumireddyОценок пока нет

- Exploring Mobile Game Addiction, Cyberbullying, and Its Effects On Academic Performance Among Tertiary Students in One University in The PhilippinesДокумент6 страницExploring Mobile Game Addiction, Cyberbullying, and Its Effects On Academic Performance Among Tertiary Students in One University in The PhilippinesJr BagaporoОценок пока нет

- Likertscale Explored ExplainedДокумент8 страницLikertscale Explored ExplainedFauzul AzhimahОценок пока нет

- Likert Scale Statistic ReportДокумент26 страницLikert Scale Statistic ReportAbegail G. ParasОценок пока нет

- Consumer Preference and Loyalty For Purchase of Processed Banana Products in Makassar CityДокумент7 страницConsumer Preference and Loyalty For Purchase of Processed Banana Products in Makassar CityAJHSSR JournalОценок пока нет

- The Learning Environment As A Mediating Variable Between Self-Directed Learning ReadinessДокумент6 страницThe Learning Environment As A Mediating Variable Between Self-Directed Learning ReadinessMagno AquinoОценок пока нет

- Service Quality of HDFC BankДокумент73 страницыService Quality of HDFC BankPreet Josan80% (5)

- Group 5-Development of Assessment ToolsДокумент48 страницGroup 5-Development of Assessment ToolsRhea P. BingcangОценок пока нет

- Comm Research Final PaperДокумент19 страницComm Research Final Paperapi-528626923Оценок пока нет

- Employee Welfare and Satisfaction in Punjab ChemicalsДокумент168 страницEmployee Welfare and Satisfaction in Punjab ChemicalsRaj_59057Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 3Документ1 страницаChapter 3Russel Bea SiasonОценок пока нет

- Measurement and Likert Scales PDFДокумент3 страницыMeasurement and Likert Scales PDFZorille dela CruzОценок пока нет