Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

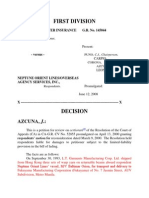

3l/epuhlic of Tbe: Versus

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

3l/epuhlic of Tbe: Versus

Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

3L\epuhlic of tbe

;ilmanila

THIRD DIVISION

WESTWIND SHIPPING

CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

- versus -

UCPB GENERAL INSURANCE

CO., INC. and ASIAN

TERMINALS, INC.,

Respondents.

x---------------------------------------x

ORIENT FREIGHT

INTERNATIONAL, INC.,

Petitioner,

- versus -

UCPB GENERAL INSURANCE

CO., INC. and ASIAN

TERMINALS, INC.,

Respondents.

G.R. No. 200289

G.R. No. 200314

Present:

VELASCO, JR., J., Chairperson,

PERALTA,

BERSAMIN,*

ABAD, and

MENDOZA, JJ.

Promulgated:

November 25, 2013

.

DECISION

PERAL TA, J.:

two consolidated cases challenge, by way of petition for

certiorari under Rule 45 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, the

Designated as Acting Member in lieu of Associate Justice Marvic Mario Victor F. Leonen, per

Special Order No. 1605 dated November 20, 2013.

Decision 2 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

September 13, 2011 Decision

1

and J anuary 19, 2012 Resolution

2

of the

Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. CV No. 86752, which reversed and set

aside the J anuary 27, 2006 Decision

3

of the Manila City Regional Trial

Court Branch (RTC) 30.

The facts, as established by the records, are as follows:

On August 23, 1993, Kinsho-Mataichi Corporation shipped from the

port of Kobe, J apan, 197 metal containers/skids of tin-free steel for delivery

to the consignee, San Miguel Corporation (SMC). The shipment, covered

by Bill of Lading No. KBMA-1074,

4

was loaded and received clean on

board M/V Golden Harvest Voyage No. 66, a vessel owned and operated by

Westwind Shipping Corporation (Westwind).

SMC insured the cargoes against all risks with UCPB General

Insurance Co., Inc. (UCPB) for US Dollars: One Hundred Eighty-Four

Thousand Seven Hundred Ninety-Eight and Ninety-Seven Centavos

(US$184,798.97), which, at the time, was equivalent to Philippine Pesos:

Six Million Two Hundred Nine Thousand Two Hundred Forty-Five and

Twenty-Eight Centavos (6,209,245.28).

The shipment arrived in Manila, Philippines on August 31, 1993 and

was discharged in the custody of the arrastre operator, Asian Terminals, Inc.

(ATI), formerly Marina Port Services, Inc.

5

During the unloading operation,

however, six containers/skids worth Philippine Pesos: One Hundred

Seventeen Thousand Ninety-Three and Twelve Centavos (117,093.12)

sustained dents and punctures from the forklift used by the stevedores of

Ocean Terminal Services, Inc. (OTSI) in centering and shuttling the

containers/skids. As a consequence, the local ship agent of the vessel,

Baliwag Shipping Agency, Inc., issued two Bad Order Cargo Receipt dated

September 1, 1993.

On September 7, 1993, Orient Freight International, Inc. (OFII), the

customs broker of SMC, withdrew from ATI the 197 containers/skids,

including the six in damaged condition, and delivered the same at SMCs

warehouse in Calamba, Laguna through J .B. Limcaoco Trucking (J BL). It

was discovered upon discharge that additional nine containers/skids valued

at Philippine Pesos: One Hundred Seventy-Five Thousand Six Hundred

Thirty-Nine and Sixty-Eight Centavos (175,639.68) were also damaged

1

Penned by Associate J ustice Elihu A. Ybaez, with Associate J ustices Estela M. Perlas-Bernabe

(now Supreme Court Associate J ustice) and Remedios Salazar-Fernando, concurring; rollo (G.R. 200289),

pp. 7-29, (G.R. 200314), pp. 25-47.

2

Rollo (G.R. 200289), pp. 31-33; rollo (G.R. 200314), pp. 49-51.

3

Id. at 79-88, id. at 59-68.

4

Rollo (G.R. 200289), p. 63.

5

Records, p. 343.

Decision 3 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

due to the forklift operations; thus, making the total number of 15

containers/skids in bad order.

Almost a year after, on August 15, 1994, SMC filed a claim against

UCPB, Westwind, ATI, and OFII to recover the amount corresponding to

the damaged 15 containers/skids. When UCPB paid the total sum of

Philippine Pesos: Two Hundred Ninety-Two Thousand Seven Hundred

Thirty-Two and Eighty Centavos (292,732.80), SMC signed the

subrogation receipt. Thereafter, in the exercise of its right of subrogation,

UCPB instituted on August 30, 1994 a complaint for damages against

Westwind, ATI, and OFII.

6

After trial, the RTC dismissed UCPBs complaint and the

counterclaims of Westwind, ATI, and OFII. It ruled that the right, if any,

against ATI already prescribed based on the stipulation in the 16 Cargo Gate

Passes issued, as well as the doctrine laid down in International Container

Terminal Services, Inc. v. Prudential Guarantee & Assurance Co. Inc.

7

that

a claim for reimbursement for damaged goods must be filed within 15 days

from the date of consignees knowledge. With respect to Westwind, even if

the action against it is not yet barred by prescription, conformably with

Section 3 (6) of the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA) and Our rulings

in E.E. Elser, Inc., et al. v. Court of Appeals, et al.

8

and Belgian Overseas

Chartering and Shipping N.V. v. Phil. First Insurance Co., Inc.,

9

the court a

quo still opined that Westwind is not liable, since the discharging of the

cargoes were done by ATI personnel using forklifts and that there was no

allegation that it (Westwind) had a hand in the conduct of the stevedoring

operations. Finally, the trial court likewise absolved OFII from any liability,

reasoning that it never undertook the operation of the forklifts which caused

the dents and punctures, and that it merely facilitated the release and

delivery of the shipment as the customs broker and representative of SMC.

On appeal by UCPB, the CA reversed and set aside the trial court. The

fallo of its September 13, 2011 Decision directed:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant appeal is hereby

GRANTED. The Decision dated J anuary 27, 2006 rendered by the court a

quo is REVERSED AND SET ASIDE. Appellee Westwind Shipping

Corporation is hereby ordered to pay to the appellant UCPB General

Insurance Co., Inc., the amount of One Hundred Seventeen Thousand and

Ninety-Three Pesos and Twelve Centavos (Php117,093.12), while Orient

Freight International, Inc. is hereby ordered to pay to UCPB the sum of

One Hundred Seventy-Five Thousand Six Hundred Thirty-Nine Pesos and

Sixty-Eight Centavos (Php175,639.68). Both sums shall bear interest at

6

Id. at 1-8; rollo (G.R. 200289), pp. 59-62.

7

377 Phil. 1082 (1999).

8

96 Phil. 264 (1954).

9

432 Phil. 567 (2002).

Decision 4 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

the rate of six (6%) percent per annum, from the filing of the complaint on

August 30, 1994 until the judgment becomes final and executory.

Thereafter, an interest rate of twelve (12%) percent per annum shall be

imposed from the time this decision becomes final and executory until full

payment of said amounts.

SO ORDERED.

10

While the CA sustained the RTC judgment that the claim against ATI

already prescribed, it rendered a contrary view as regards the liability of

Westwind and OFII. For the appellate court, Westwind, not ATI, is

responsible for the six damaged containers/skids at the time of its unloading.

In its rationale, which substantially followed Philippines First Insurance

Co., Inc. v. Wallem Phils. Shipping, Inc.,

11

it concluded that the common

carrier, not the arrastre operator, is responsible during the unloading of the

cargoes from the vessel and that it is not relieved from liability and is still

bound to exercise extraordinary diligence at the time in order to see to it that

the cargoes under its possession remain in good order and condition. The CA

also considered that OFII is liable for the additional nine damaged

containers/skids, agreeing with UCPBs contention that OFII is a common

carrier bound to observe extraordinary diligence and is presumed to be at

fault or have acted negligently for such damage. Noting the testimony of

OFIIs own witness that the delivery of the shipment to the consignee is part

of OFIIs job as a cargo forwarder, the appellate court ruled that Article

1732 of the New Civil Code (NCC) does not distinguish between one whose

principal business activity is the carrying of persons or goods or both and

one who does so as an ancillary activity. The appellate court further ruled

that OFII cannot excuse itself from liability by insisting that J BL undertook

the delivery of the cargoes to SMCs warehouse. It opined that the delivery

receipts signed by the inspector of SMC showed that the containers/skids

were received from OFII, not J BL. At the most, the CA said, J BL was

engaged by OFII to supply the trucks necessary to deliver the shipment,

under its supervision, to SMC.

Only Westwind and OFII filed their respective motions for

reconsideration, which the CA denied; hence, they elevated the case before

Us via petitions docketed as G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314, respectively.

Westwind argues that it no longer had actual or constructive custody

of the containers/skids at the time they were damaged by ATIs forklift

operator during the unloading operations. In accordance with the stipulation

of the bill of lading, which allegedly conforms to Article 1736 of the NCC, it

contends that its responsibility already ceased from the moment the cargoes

were delivered to ATI, which is reckoned from the moment the goods were

taken into the latters custody. Westwind adds that ATI, which is a

10

Rollo (G.R. 200289), pp. 27-28, rollo (G.R. 200314), pp. 45-46. (Emphasis in the original)

11

G.R. No. 165647, March 26, 2009, 582 SCRA 457.

Decision 5 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

completely independent entity that had the right to receive the goods as

exclusive operator of stevedoring and arrastre functions in South Harbor,

Manila, had full control over its employees and stevedores as well as the

manner and procedure of the discharging operations.

As for OFII, it maintains that it is not a common carrier, but only a

customs broker whose participation is limited to facilitating withdrawal of

the shipment in the custody of ATI by overseeing and documenting the

turnover and counterchecking if the quantity of the shipments were in tally

with the shipping documents at hand, but without participating in the

physical withdrawal and loading of the shipments into the delivery trucks of

J BL. Assuming that it is a common carrier, OFII insists that there is no need

to rely on the presumption of the law that, as a common carrier, it is

presumed to have been at fault or have acted negligently in case of damaged

goods considering the undisputed fact that the damages to the

containers/skids were caused by the forklift blades, and that there is no

evidence presented to show that OFII and Westwind were the

owners/operators of the forklifts. It asserts that the loading to the trucks were

made by way of forklifts owned and operated by ATI and the unloading

from the trucks at the SMC warehouse was done by way of forklifts owned

and operated by SMC employees. Lastly, OFII avers that neither the

undertaking to deliver nor the acknowledgment by the consignee of the fact

of delivery makes a person or entity a common carrier, since delivery alone

is not the controlling factor in order to be considered as such.

Both petitions lack merit.

The case of Philippines First Insurance Co., Inc. v. Wallem Phils.

Shipping, Inc.

12

applies, as it settled the query on which between a common

carrier and an arrastre operator should be responsible for damage or loss

incurred by the shipment during its unloading. We elucidated at length:

Common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons

of public policy, are bound to observe extraordinary diligence in the

vigilance over the goods transported by them. Subject to certain

exceptions enumerated under Article 1734 of the Civil Code, common

carriers are responsible for the loss, destruction, or deterioration of the

goods. The extraordinary responsibility of the common carrier lasts from

the time the goods are unconditionally placed in the possession of, and

received by the carrier for transportation until the same are delivered,

actually or constructively, by the carrier to the consignee, or to the person

who has a right to receive them.

For marine vessels, Article 619 of the Code of Commerce provides

that the ship captain is liable for the cargo from the time it is turned over

to him at the dock or afloat alongside the vessel at the port of loading,

12

Id.

Decision 6 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

until he delivers it on the shore or on the discharging wharf at the port of

unloading, unless agreed otherwise. In Standard Oil Co. of New York v.

Lopez Castelo, the Court interpreted the ship captains liability as

ultimately that of the shipowner by regarding the captain as the

representative of the shipowner.

Lastly, Section 2 of the COGSA provides that under every contract

of carriage of goods by sea, the carrier in relation to the loading, handling,

stowage, carriage, custody, care, and discharge of such goods, shall be

subject to the responsibilities and liabilities and entitled to the rights and

immunities set forth in the Act. Section 3 (2) thereof then states that

among the carriers responsibilities are to properly and carefully load,

handle, stow, carry, keep, care for, and discharge the goods carried.

x x x x

On the other hand, the functions of an arrastre operator involve the

handling of cargo deposited on the wharf or between the establishment of

the consignee or shipper and the ship's tackle. Being the custodian of the

goods discharged from a vessel, an arrastre operator's duty is to take good

care of the goods and to turn them over to the party entitled to their

possession.

Handling cargo is mainly the arrastre operator's principal work so

its drivers/operators or employees should observe the standards and

measures necessary to prevent losses and damage to shipments under its

custody.

In Firemans Fund Insurance Co. v. Metro Port Service, Inc., the

Court explained the relationship and responsibility of an arrastre operator

to a consignee of a cargo, to quote:

The legal relationship between the consignee and the

arrastre operator is akin to that of a depositor and

warehouseman. The relationship between the consignee

and the common carrier is similar to that of the consignee

and the arrastre operator. Since it is the duty of the

ARRASTRE to take good care of the goods that are in its

custody and to deliver them in good condition to the

consignee, such responsibility also devolves upon the

CARRIER. Both the ARRASTRE and the CARRIER

are therefore charged with and obligated to deliver the

goods in good condition to the consignee. (Emphasis

supplied) (Citations omitted)

The liability of the arrastre operator was reiterated in Eastern

Shipping Lines, Inc. v. Court of Appeals with the clarification that the

arrastre operator and the carrier are not always and necessarily solidarily

liable as the facts of a case may vary the rule.

Thus, in this case, the appellate court is correct insofar as it

ruled that an arrastre operator and a carrier may not be held

solidarily liable at all times. But the precise question is which entity

had custody of the shipment during its unloading from the vessel?

Decision 7 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

The aforementioned Section 3 (2) of the COGSA states that

among the carriers responsibilities are to properly and carefully load,

care for and discharge the goods carried. The bill of lading covering

the subject shipment likewise stipulates that the carriers liability for

loss or damage to the goods ceases after its discharge from the vessel.

Article 619 of the Code of Commerce holds a ship captain liable for

the cargo from the time it is turned over to him until its delivery at the

port of unloading.

In a case decided by a U.S. Circuit Court, Nichimen Company

v. M/V Farland, it was ruled that like the duty of seaworthiness, the

duty of care of the cargo is non-delegable, and the carrier is

accordingly responsible for the acts of the master, the crew, the

stevedore, and his other agents. It has also been held that it is

ordinarily the duty of the master of a vessel to unload the cargo and

place it in readiness for delivery to the consignee, and there is an

implied obligation that this shall be accomplished with sound

machinery, competent hands, and in such manner that no

unnecessary injury shall be done thereto. And the fact that a

consignee is required to furnish persons to assist in unloading a

shipment may not relieve the carrier of its duty as to such unloading.

x x x x

It is settled in maritime law jurisprudence that cargoes while

being unloaded generally remain under the custody of the carrier x x

x.

13

In Regional Container Lines (RCL) of Singapore v. The Netherlands

Insurance Co. (Philippines), Inc.

14

and Asian Terminals, Inc. v. Philam

Insurance Co., Inc.,

15

the Court echoed the doctrine that cargoes, while

being unloaded, generally remain under the custody of the carrier.

We cannot agree with Westwinds disputation that the carrier in

Wallem clearly exercised supervision during the discharge of the shipment

and that is why it was faulted and held liable for the damage incurred by the

shipment during such time. What Westwind failed to realize is that the

extraordinary responsibility of the common carrier lasts until the time the

goods are actually or constructively delivered by the carrier to the consignee

or to the person who has a right to receive them. There is actual delivery in

contracts for the transport of goods when possession has been turned over to

the consignee or to his duly authorized agent and a reasonable time is given

him to remove the goods.

16

In this case, since the discharging of the

containers/skids, which were covered by only one bill of lading, had not yet

been completed at the time the damage occurred, there is no reason to imply

13

Philippines First Insurance Co., Inc. v. Wallem Phils. Shipping, Inc., supra note 11, at 466-472.

(Emphasis supplied)

14

G.R. No. 168151, September 4, 2009, 598 SCRA 304.

15

G.R. Nos. 181163, 181262 and 181319, J uly 24, 2013.

16

Samar Mining Company, Inc. v. Nordeutscher Lloyd and C.F. Sharp & Company, Inc., 217 Phil.

497, 506 (1984), citing 11Words and Phrases 676, citing Yazoo & MVR Company v. Altman, 187 SW 656,

657.

Decision 8 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

that there was already delivery, actual or constructive, of the cargoes to ATI.

Indeed, the earlier case of Delsan Transport Lines, Inc. v. American Home

Assurance Corp.

17

serves as a useful guide, thus:

Delsans argument that it should not be held liable for the loss of

diesel oil due to backflow because the same had already been actually and

legally delivered to Caltex at the time it entered the shore tank holds no

water. It had been settled that the subject cargo was still in the custody of

Delsan because the discharging thereof has not yet been finished when the

backflow occurred. Since the discharging of the cargo into the depot has

not yet been completed at the time of the spillage when the backflow

occurred, there is no reason to imply that there was actual delivery of the

cargo to the consignee. Delsan is straining the issue by insisting that when

the diesel oil entered into the tank of Caltex on shore, there was legally, at

that moment, a complete delivery thereof to Caltex. To be sure, the

extraordinary responsibility of common carrier lasts from the time the

goods are unconditionally placed in the possession of, and received by, the

carrier for transportation until the same are delivered, actually or

constructively, by the carrier to the consignee, or to a person who has the

right to receive them. The discharging of oil products to Caltex Bulk

Depot has not yet been finished, Delsan still has the duty to guard and to

preserve the cargo. The carrier still has in it the responsibility to guard and

preserve the goods, a duty incident to its having the goods transported.

To recapitulate, common carriers, from the nature of their business

and for reasons of public policy, are bound to observe extraordinary

diligence in vigilance over the goods and for the safety of the passengers

transported by them, according to all the circumstances of each case. The

mere proof of delivery of goods in good order to the carrier, and their

arrival in the place of destination in bad order, make out a prima facie case

against the carrier, so that if no explanation is given as to how the injury

occurred, the carrier must be held responsible. It is incumbent upon the

carrier to prove that the loss was due to accident or some other

circumstances inconsistent with its liability.

18

The contention of OFII is likewise untenable. A customs broker has

been regarded as a common carrier because transportation of goods is an

integral part of its business.

19

In Schmitz Transport & Brokerage

Corporation v. Transport Venture, Inc.,

20

the Court already reiterated:

It is settled that under a given set of facts, a customs broker may be

regarded as a common carrier. Thus, this Court, in A.F. Sanchez

Brokerage, Inc. v. The Honorable Court of Appeals held:

The appellate court did not err in finding petitioner, a

customs broker, to be also a common carrier, as defined

under Article 1732 of the Civil Code, to wit,

17

530 Phil. 332 (2006).

18

Delsan Transport Lines, Inc. v. American Home Assurance Corp., supra, at 340-341.

19

Loadmasters Customs Services, Inc. v. Glodel Brokerage Corporation, G.R. No. 179446, J anuary

10, 2011, 639 SCRA 69, 80.

20

496 Phil. 437 (2005).

Decision 9 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

Art. 1732. Common carriers are persons, corporations,

firms or associations engaged in the business of carrying or

transporting passengers or goods or both, by land, water, or

air, for compensation, offering their services to the public.

x x x x

Article 1732 does not distinguish between one whose

principal business activity is the carrying of goods and one

who does such carrying only as an ancillary activity. The

contention, therefore, of petitioner that it is not a common

carrier but a customs broker whose principal function is to

prepare the correct customs declaration and proper shipping

documents as required by law is bereft of merit. It suffices

that petitioner undertakes to deliver the goods for pecuniary

consideration.

And in Calvo v. UCPB General Insurance Co. Inc., this Court held

that as the transportation of goods is an integral part of a customs broker,

the customs broker is also a common carrier. For to declare otherwise

would be to deprive those with whom [it] contracts the protection which

the law affords them notwithstanding the fact that the obligation to carry

goods for [its] customers, is part and parcel of petitioners business.

21

That OFII is a common carrier is buttressed by the testimony of its

own witness, Mr. Loveric Panganiban Cueto, that part of the services it

offers to clients is cargo forwarding, which includes the delivery of the

shipment to the consignee.

22

Thus, for undertaking the transport of cargoes

from ATI to SMCs warehouse in Calamba, Laguna, OFII is considered a

common carrier. As long as a person or corporation holds itself to the public

for the purpose of transporting goods as a business, it is already considered a

common carrier regardless of whether it owns the vehicle to be used or has

to actually hire one.

As a common carrier, OFII is mandated to observe, under Article

1733 of the Civil Code,

23

extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the

goods

24

it transports according to the peculiar circumstances of each case. In

the event that the goods are lost, destroyed or deteriorated, it is presumed to

21

Schmitz Transport & Brokerage Corporation v. Transport Venture, Inc., supra, at 450-551.

22

TSN, February 1, 1999, p. 11.

23

Art. 1733. Common carriers, from the nature of their business and for reasons of public policy, are

bound to observe extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods and for the safety of the

passengers transported by them, according to all the circumstances of each case.

x x x x

24

In Compania Maritima v. Court of Appeals (G.R. No. L-31379, August 29, 1958, 164 SCRA 685,

692), the meaning of extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over goods was explained, thus:

The extraordinary diligence in the vigilance over the goods tendered for shipment requires

the common carrier to know and to follow the required precaution for avoiding damage to, or

destruction of the goods entrusted to it for safe carriage and delivery. It requires common

carriers to render service with the greatest skill and foresight and to use all reasonable means to

ascertain the nature and characteristic of goods tendered for shipment, and to exercise due care

in the handling and stowage, including such methods as their nature requires.

Decision 10 G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314

have been at fault or to have acted negligently, unless it proves that it

observed extraordinary diligence.

25

In the case at bar, it was established that,

except for the six containers/skids already damaged, OFII received the

cargoes from ATI in good order and condition; and that upon its delivery to

SMC, additional nine containers/skids were found to be in bad order, as

noted in the Delivery Receipts issued by OFII and as indicated in the Report

of Cares Marine & Cargo Surveyors. Instead of merely excusing itself from

liability by putting the blame to ATI and SMC, it is incumbent upon OFII to

prove that it actively took care of the goods by exercising extraordinary

diligence in the carriage thereof. It failed to do so. Hence, its presumed

negligence under Article 1735 of the Civil Code remains unrebutted.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the petitions of Westwind and

OFII in G.R. Nos. 200289 and 200314, respectively, are DENIED. The

September 13, 2011 Decision and January 19, 2012 Resolution of the Court

of Appeals in CA-G.R. CV No. 86752, which reversed and set aside the

January 27, 2006 Decision of the Manila City Regional Trial Court, Branch

30, are AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

WE CONCUR:

PRESBITERO J VELASCO, JR.

Associ e Justice

C irperson

ROBERTO A. ABAD

Associate Justice

25

Art. 1735. In all cases other than those mentioned in Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 of the preceding article,

if the goods are lost, destroyed or deteriorated, common carriers are presumed to have been at fault or to

have acted negligently, unless they prove that they observed extraordinary diligence as required on Article

1733.

Decision

11 G.R. Nos. 200289 and200314

ENDOZA

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of the opinion of the

Court's Division.

Ass iate Justice

Chairpe on, Third Division

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution and the

Division Chairperson's Attestation, I certify that the conclusions in the

above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was

assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court's Division.

MARIA LOURDES P.A. SERENO

Chief Justice

Вам также может понравиться

- Logistics TerminologyДокумент10 страницLogistics Terminologyquanghuy061285Оценок пока нет

- Judgments of the Court of Appeal of New Zealand on Proceedings to Review Aspects of the Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Mount Erebus Aircraft Disaster C.A. 95/81От EverandJudgments of the Court of Appeal of New Zealand on Proceedings to Review Aspects of the Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Mount Erebus Aircraft Disaster C.A. 95/81Оценок пока нет

- Payslip On DeputationДокумент86 страницPayslip On DeputationAnonymous pKsr5vОценок пока нет

- Master CardДокумент22 страницыMaster CardAsef KhademiОценок пока нет

- 10135Документ7 страниц10135The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- Double Taxation Prohibition in Manila Revenue CodeДокумент8 страницDouble Taxation Prohibition in Manila Revenue CodeAna leah Orbeta-mamburamОценок пока нет

- Withholding Compensation - 1601Cv2018 FormДокумент1 страницаWithholding Compensation - 1601Cv2018 FormReynaldo PogzОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 92735 Monarch V CA - DigestДокумент2 страницыG.R. No. 92735 Monarch V CA - DigestOjie Santillan100% (1)

- Jan-19 PDFДокумент2 страницыJan-19 PDFPriya Gujar100% (1)

- Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs IACДокумент15 страницEastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs IACDarwin SolanoyОценок пока нет

- Encyclopaedia of International Aviation Law: Volume 3 English and French Version Version Englaise Et Française 2013 EditionОт EverandEncyclopaedia of International Aviation Law: Volume 3 English and French Version Version Englaise Et Française 2013 EditionОценок пока нет

- WestWind vs. UCPB General InsuranceДокумент9 страницWestWind vs. UCPB General InsuranceAnalyn Grace Yongco BasayОценок пока нет

- Westwind - Shipping - Corp. - v. - UCPB - General20210614-12-MytdhaДокумент10 страницWestwind - Shipping - Corp. - v. - UCPB - General20210614-12-MytdhaGina RothОценок пока нет

- Terminal Services, Inc. v. Prudential Guarantee & Assurance Co. IncДокумент4 страницыTerminal Services, Inc. v. Prudential Guarantee & Assurance Co. IncMae MaihtОценок пока нет

- Westwind Vs UcpbДокумент5 страницWestwind Vs UcpbHiezll Wynn R. RiveraОценок пока нет

- The Facts and Antecedent ProceedingsДокумент6 страницThe Facts and Antecedent Proceedingsmieai aparecioОценок пока нет

- Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc., Petitioner vs. Bpi/Ms Insurance Corp., and Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance CO., LTD., RespondentsДокумент59 страницEastern Shipping Lines, Inc., Petitioner vs. Bpi/Ms Insurance Corp., and Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance CO., LTD., RespondentsspecialsectionОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 147246Документ6 страницG.R. No. 147246JUAN GABONОценок пока нет

- Westwind Vs UCPBДокумент3 страницыWestwind Vs UCPBDamnum Absque InjuriaОценок пока нет

- GR 75118 Sea-Land Service Inc Vs IACДокумент12 страницGR 75118 Sea-Land Service Inc Vs IACJessie AncogОценок пока нет

- Carriers Liable for Damages Subject to LimitationДокумент6 страницCarriers Liable for Damages Subject to LimitationKier Christian Montuerto InventoОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 193986 - Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. v. BPI - MS Insurance Corp - PDFДокумент7 страницG.R. No. 193986 - Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. v. BPI - MS Insurance Corp - PDFAmielle CanilloОценок пока нет

- Cargo liability dispute between shipping lines and insurersДокумент7 страницCargo liability dispute between shipping lines and insurersAmielle CanilloОценок пока нет

- Crescent Vs M Vlok Mahesh I War IДокумент12 страницCrescent Vs M Vlok Mahesh I War IJarel ManansalaОценок пока нет

- New World International Development (Phils.), Inc. vs. NYKFilJapan Shipping CorpДокумент12 страницNew World International Development (Phils.), Inc. vs. NYKFilJapan Shipping CorpAaron CarinoОценок пока нет

- CA upholds RTC ruling holding Unitrans liable for damaged musical instrumentsДокумент7 страницCA upholds RTC ruling holding Unitrans liable for damaged musical instrumentsVener MargalloОценок пока нет

- Court upholds carrier liability for sunken cargoДокумент4 страницыCourt upholds carrier liability for sunken cargoAriann BarrosОценок пока нет

- Crescent Petroleum vs. MV Lok MaheshwariДокумент11 страницCrescent Petroleum vs. MV Lok MaheshwariAres Victor S. AguilarОценок пока нет

- Transpo 2008Документ69 страницTranspo 2008Lois DОценок пока нет

- Aboitiz Shipping Corporation v. CA (569 SCRA 294) - FULL TEXTДокумент16 страницAboitiz Shipping Corporation v. CA (569 SCRA 294) - FULL TEXTAdrian Joseph TanОценок пока нет

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Del Rosario & Del Rosario Law Office Quasha, Asperilla, Ancheta, Peña, Marcos & NolascoДокумент3 страницыPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Del Rosario & Del Rosario Law Office Quasha, Asperilla, Ancheta, Peña, Marcos & NolascoSiegfred G. PerezОценок пока нет

- 21 Asian Terminals vs. First LepantoДокумент9 страниц21 Asian Terminals vs. First LepantoMichelle Montenegro - AraujoОценок пока нет

- 36 Unsworth V CAДокумент5 страниц36 Unsworth V CAMarioneMaeThiamОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 185964Документ6 страницG.R. No. 185964ejpОценок пока нет

- New World International Dev, Inc V NYK-FilJapan Shipping CorpДокумент7 страницNew World International Dev, Inc V NYK-FilJapan Shipping CorpMacy TangОценок пока нет

- Asia Lighterage vs. Courts of Appeals G.R. No. 147246, August 19, 2003Документ7 страницAsia Lighterage vs. Courts of Appeals G.R. No. 147246, August 19, 2003RGIQОценок пока нет

- Crescent Petroleum V MV Lok MaheshwariДокумент6 страницCrescent Petroleum V MV Lok MaheshwariJJ CoolОценок пока нет

- Eastern Shipping Lines Vs BPI-MS Insurance CorporationДокумент6 страницEastern Shipping Lines Vs BPI-MS Insurance CorporationEl G. Se ChengОценок пока нет

- Insurance CasesДокумент121 страницаInsurance CasessuijurisОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. 182864, January 12, 2015 Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs BPIДокумент11 страницG.R. No. 182864, January 12, 2015 Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. Vs BPIJavieОценок пока нет

- Eastern Shipping Lines v. IAC (L-69044)Документ6 страницEastern Shipping Lines v. IAC (L-69044)Josef MacanasОценок пока нет

- Loadstar Shipping vs. Pioneer AsiaДокумент7 страницLoadstar Shipping vs. Pioneer AsiaKrisleen AbrenicaОценок пока нет

- Crescent Petroleum Vs MV LokДокумент17 страницCrescent Petroleum Vs MV LokRv LacayОценок пока нет

- 6 Eastern Shipping LinesДокумент4 страницы6 Eastern Shipping LinesMary Louise R. ConcepcionОценок пока нет

- GR No. 145044 - PCIC Vs Neptune Orient LinesДокумент10 страницGR No. 145044 - PCIC Vs Neptune Orient LinesJobi BryantОценок пока нет

- Cases in Transpo 3Документ77 страницCases in Transpo 3Angelique Giselle CanaresОценок пока нет

- Land Transpotation Cases (Recovered)Документ150 страницLand Transpotation Cases (Recovered)Notaly Mae Paja BadtingОценок пока нет

- Insurance Dispute over Damaged Vehicle PartsДокумент16 страницInsurance Dispute over Damaged Vehicle PartsSiegfred G. PerezОценок пока нет

- 16 Asian Terminal V Philam InsuranceДокумент16 страниц16 Asian Terminal V Philam InsuranceFrances Angelica Domini KoОценок пока нет

- Land Transpotation CasesДокумент159 страницLand Transpotation CasesNotaly Mae Paja BadtingОценок пока нет

- 29) Phil First Ins Co., Inc. vs. Wallem Phils. Shipping, Inc., Et Al. G.R. No. 165647, March 26, 2009Документ7 страниц29) Phil First Ins Co., Inc. vs. Wallem Phils. Shipping, Inc., Et Al. G.R. No. 165647, March 26, 2009S.G.T.Оценок пока нет

- ABOITIZ SHIPPING CORPORATION, Vs - INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA, G.R. No. 168402 August 6, 2008Документ9 страницABOITIZ SHIPPING CORPORATION, Vs - INSURANCE COMPANY OF NORTH AMERICA, G.R. No. 168402 August 6, 2008Christopher ArellanoОценок пока нет

- 5Документ11 страниц5Hanifa D. Al-ObinayОценок пока нет

- Shipping Contract Dispute ResolvedДокумент14 страницShipping Contract Dispute ResolvedUfbОценок пока нет

- Phil Charter Ins Corp V Neptune Orient LinesДокумент8 страницPhil Charter Ins Corp V Neptune Orient LinesmcsumpayОценок пока нет

- Transpo To PrintДокумент29 страницTranspo To PrintRajh EfondoОценок пока нет

- UCPB Gen. Insurance vs. AboitizДокумент4 страницыUCPB Gen. Insurance vs. AboitizaudreyОценок пока нет

- Crescent Petroleum, Ltd. v. MV Lok Maheshwari, Et Al G.R. No. 155014Документ8 страницCrescent Petroleum, Ltd. v. MV Lok Maheshwari, Et Al G.R. No. 155014FeBrluadoОценок пока нет

- Evid Cases Feb 4Документ44 страницыEvid Cases Feb 4Louie SalladorОценок пока нет

- Unsworth Transport International (Phils.), Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals - G.R. No. 166250Документ5 страницUnsworth Transport International (Phils.), Inc., Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals - G.R. No. 166250Song OngОценок пока нет

- 051 G.R. No. 137775. March 31, 2005 FGU Corp Vs CAДокумент7 страниц051 G.R. No. 137775. March 31, 2005 FGU Corp Vs CArodolfoverdidajr100% (1)

- NDF Vs CA 164 Scra 593Документ6 страницNDF Vs CA 164 Scra 593CiroОценок пока нет

- AsialighterageДокумент6 страницAsialighteragemieai aparecioОценок пока нет

- Aboitiz V CAДокумент8 страницAboitiz V CAPrincess AyomaОценок пока нет

- 188576-2005-Crescent Petroleum Ltd. v. M V LokДокумент12 страниц188576-2005-Crescent Petroleum Ltd. v. M V LokLynne AgapitoОценок пока нет

- Asian Terminals, Inc V Philam Insurance Co GR No 181163 July 24 2013Документ15 страницAsian Terminals, Inc V Philam Insurance Co GR No 181163 July 24 2013Kharol EdeaОценок пока нет

- 166995Документ15 страниц166995The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 159926Документ14 страниц159926The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- P 13 3126Документ8 страницP 13 3126The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 187973Документ10 страниц187973The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 183880Документ13 страниц183880The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 164985Документ10 страниц164985The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- RTJ 14 2367Документ7 страницRTJ 14 2367The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 190928Документ11 страниц190928The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 197760Документ11 страниц197760The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 196171Документ5 страниц196171The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 160600Документ8 страниц160600The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- P 12 3069Документ13 страницP 12 3069The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 164246Документ7 страниц164246The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 199226Документ10 страниц199226The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 200304Документ18 страниц200304The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 192479Документ6 страниц192479The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 201092Документ15 страниц201092The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 183204Документ12 страниц183204The Supreme Court Public Information Office100% (1)

- 188747Документ10 страниц188747The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- P 08 2574Документ10 страницP 08 2574The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 198804Документ15 страниц198804The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- RTJ 11 2287Документ10 страницRTJ 11 2287The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 185798Документ10 страниц185798The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 172551Документ17 страниц172551The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 192034Документ18 страниц192034The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 176043Документ18 страниц176043The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 178564Документ12 страниц178564The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- BrionДокумент18 страницBrionThe Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- 183015Документ9 страниц183015The Supreme Court Public Information OfficeОценок пока нет

- XII ScienceДокумент1 страницаXII ScienceShahzaib MughalОценок пока нет

- Branches in Sarawak: Kuching Laksamana MiriДокумент1 страницаBranches in Sarawak: Kuching Laksamana MiridomromeoОценок пока нет

- Bill of LadingДокумент1 страницаBill of Ladingapi-306311564Оценок пока нет

- Growth SaverДокумент9 страницGrowth SaverKugilan BalakrishnanОценок пока нет

- BLR To DelДокумент2 страницыBLR To Del786rohitsandujaОценок пока нет

- Jupiter Thane POДокумент4 страницыJupiter Thane POAnonymous SXTKyUsОценок пока нет

- عسکری بینکДокумент39 страницعسکری بینکNain TechnicalОценок пока нет

- Recurring Deposit Installment Report SummaryДокумент2 страницыRecurring Deposit Installment Report SummaryChiranjeevi GunturuОценок пока нет

- Nursery 1: 4 Weeks To 18 Months: Baby Atelier Nursery & Preschool 2021 Program FeesДокумент1 страницаNursery 1: 4 Weeks To 18 Months: Baby Atelier Nursery & Preschool 2021 Program FeesYap Wai KietОценок пока нет

- CDoc - Taxation Law Project TopicsДокумент3 страницыCDoc - Taxation Law Project TopicsFaizan Bin Abdul HakeemОценок пока нет

- Ship From: Grand TotalДокумент2 страницыShip From: Grand TotalDian Ayu PuspitasariОценок пока нет

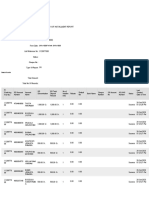

- Account Statement From 1 Feb 2022 To 31 Jan 2023: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceДокумент15 страницAccount Statement From 1 Feb 2022 To 31 Jan 2023: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceAarti ThdfcОценок пока нет

- Comp ProjectДокумент28 страницComp Projectavram johnОценок пока нет

- Tax System in CambodiaДокумент11 страницTax System in CambodiaHang VeasnaОценок пока нет

- Post-Closing Trial BalanceДокумент3 страницыPost-Closing Trial BalanceSuszie Sue70% (10)

- Pre Taipei Cycle ShowДокумент25 страницPre Taipei Cycle ShowGoodBikesОценок пока нет

- Rea Vaya South Africa's First Bus Rapid Transit SystemДокумент3 страницыRea Vaya South Africa's First Bus Rapid Transit Systemdaotuan851Оценок пока нет

- July Adib 2011 ReconciliationДокумент15 страницJuly Adib 2011 ReconciliationgulamdastageerОценок пока нет

- 4ME Brochure Update V2657Документ12 страниц4ME Brochure Update V2657ElijahОценок пока нет

- QTBD SimulationДокумент133 страницыQTBD SimulationSaptarshi BhowmikОценок пока нет

- Strand7 Documentation Order FormДокумент1 страницаStrand7 Documentation Order FormNick BesterОценок пока нет

- PDFДокумент5 страницPDFBuşuMihaiCătălinОценок пока нет

- Uzor, Blessing Amarachukwu: Trans. Date Reference Value Date Debit Credit Balance RemarksДокумент5 страницUzor, Blessing Amarachukwu: Trans. Date Reference Value Date Debit Credit Balance RemarksThank GodОценок пока нет

- Class4-Traffic CharacteristicsДокумент16 страницClass4-Traffic CharacteristicsYihun abrahamОценок пока нет