Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Infraestructure A Political Analysis

Загружено:

reginaxyИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Infraestructure A Political Analysis

Загружено:

reginaxyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

-1-

INFRASTRUCTURE:

A POLITICAL ANALYSIS by

Theodore J. Lowi Department of Government Cornell University

presented at Institute for Civil Infrastructure Systems (ICIS) Coordinated Renewal of the Civil Infrastructure Systems for Sustainable Human Environments April 21-22, 1999

-2-

The enormous American national debt is perfectly justifiable. the Cold War. We used it to pay for victory in World War II and There was waste aplenty, but the need for

redundancy to sustain urgent projects through the unexpected is almost always justifiable. Also justifiable is the financing of

hot war and cold war by long-term debt, because our children and their children should help pay for the victories their parents and grandparents gave them. The same goes for any large public

works, whose financing should be spread across a large portion of its useful life. But $2-4 billion in accumulated and deferred

maintenance costs of the 45,744-mile U.S. Interstate Highway system is evidence of the sheer idiocy of leaving infrastructure to Congress, to cost benefit analysis, to civil engineers and to consulting economists. Moreover, the unplanned and

unanticipated, and, mostly unwanted, social uses of public works, especially arterial highways, have to be taken into account. "war is much too serious a matter to be entrusted to the military" (Clemenceau) we must add that "civil infrastructure is too important to be entrusted to engineers." If "civil infrastructure" is translated back into ordinary language, it is part of what we have traditionally called public works, and this translation reveals the oldest policy activity of the national government of the United States. Moreover the If

politics of this area of public policy is familiar and wellstudied. Thus, it would seem that we ought to be able to draw

-3-

some lessons from this literature that can be applied directly to the phenomena of modern civil infrastructure. My task, as I see

it, is to explore what, if anything, a political analysis can contribute to the understanding of infrastructure, how we got to where we are with it, and how we might improve our chances of getting to a more sustainable future.

WHAT IS INFRASTRUCTURE? The Oxford English Dictionary defines infrastructure as "a collective term for the subordinate parts of an undertaking; substructure, foundation ... the permanent installations forming a basis for military operations ...." William Safire in his

humorous but instructive Political Dictionary, defines it as "skeleton; a political entity's internal administrative apparatus." He correctly characterizes it as a "bit of jargon,"

because its origin and purpose can be specifically identified. Oxford dates the first use with 1927, in a military context, and then attaches it to World War II. By 1950, Churchill stood

before the House of Commons and denounced the word while recognizing that it was probably impossible to expunge it from the English language. military contexts. Adding "civic" or "civil" to it as an adjective to infrastructure focuses the phenomenon on most projects of whatever sort are financed and built by governments, or in a It is still used most frequently in

-4-

mixed public/private endeavor in which the government role is essential. Whatever the case, the general category can and Infrastructure can be readily

should be called public works.

classified as a sub-category of the generic category of public works. I would venture to offer here a criterion for

distinguishing civil infrastructure as a category within public works as follows: Civil infrastructure is a public works project

which occupies such a strategic place in a geographic area or an economically definable one that the project produces intended and unintended consequences out into the indefinite future, with an influence not only on future public and private land uses but on the virtual process of thinking and planning itself, for a large but indefinite space around the project. Such strategically

located projects can be called paradigmatic public works, with secondary and tertiary effects that not only influence investment but thinking and design (i.e., planning) in concentric circles of space and data around the given civil infrastructure project. can follow here what Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart said about pornography: Though we cannot necessarily define civil We

infrastructure to everybody's satisfaction, we know it when we see it.

TOWARD A POLITICAL DEFINITION OF INFRASTRUCTURE POLICY A point made in the previous section could well be considered the governing premise of this endeavor:

-5-

infrastructure policy is an organic part of the category of public works policy and as such is part of the oldest continuing category of public policy in the government of the United States. Just after the conquest of the territory and the defense of the new state, with a bit of an army and some taxation, public works is probably the oldest definable public policy category everywhere -- even before policies protecting private property. (I would consider relevant infrastructure as one of the basic prerequisites of an operating market economy.) Public works

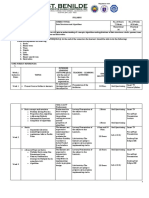

policy is the cornerstone of government and of politics in the United States. To appreciate this, we need a short course in public policy, in order to specify the various kinds of public policies to which public works policies can be compared -- defining what public works policy is and what it is not. I begin here with history Table 1 is a

rather than with a direct definition.

pictorialization of the public policy outputs of each of the levels of government in the United States, from roughly 1800 to 1933. First examine Column 1, the domestic policy output of The first notable The

Congress throughout the 19th century.

impression is that all these items share two common traits. first is common purpose:

the promotion or husbandry of commerce.

So prominent and so well understood was this that many Europeans referred to the early American government as a "commercial republic." And indeed, the coup d'etat that moved us from the

-6-

Articles of Confederation to the Constitution was precisely driven by frustration with the barriers to regional and national commerce under the first American republic. The second common

trait is that all of these items of policy use government in same way: In the promotion of commerce, there is no involvement of All policies are coercive,

direct coercion over individuals.

because they are governmental; but, as we shall see, there are different kinds of coercion. Column 1 is better appreciated in the context of Column 2, policy outputs of state governments. State governments did a lot

of the same kind of promotion of commerce that the national government did, especially through their local creatures, called cities, counties, etc. But the distinctive feature of state

policy outputs, as shown on Column 2, is something else entirely. It does not take much reflection on the items in that long column to find what that is. And I should emphasize that each of

these items is a basket of policies represented by at least one volume in state codes of legislation. The common trait through

those items is referred to in constitutional history as "the police power." The modern rendering of that concept is: This is a particular and distinctive use of

regulatory policy.

state coercion, which involves the imposition of obligations on conduct, backed by sanctions. From that distinction alone, I think we can gain a clear picture of the nature of "public works" as a distinct category of

-7-

policy.

(This, by the way, gives also a clear picture of the

true nature of federalism, as a form of functional division of power.) The classic examples of such policies are housed in a

classic agency, the Army Corps of Engineers, possibly the oldest continuing agency in the national government, with the possible exception of the Postal Service. [PROVIDE DATES OF FOUNDING]

The original assignment of the Corps of Engineers, "Rivers and Harbors," became the trade name for the whole category of public works, whose affectionate popular name became "pork barrel." this brings us closer to a functional definition of the whole category, because the best guess is that "pork barrel" comes from the ante-bellum practice of distributing chunks of salt pork to slaves in large barrels, permitting them to fight over the barrel and grab as many chunks as they could possibly carry away. the pieces of pork in the barrel, promotional policies are policies that actually distribute valued resources to individuals in order to expand their alternatives or enable them to do something they were otherwise not able to do. And these valued Like And

resources can be disaggregated into larger and larger numbers of smaller and smaller chunks, like pork in the barrel. Table 2

labels these "distributive policies," a term chosen in order to distinguish these from regulatory policies and from "redistributive" policies (of which more in a moment). But the

best way to understand the distributive policies is to understand them as a particular use of the state called patronage.

-8-

Patronage has been vulgarized to refer only to the public jobs and other individual privileges that the victorious political party can distribute to the faithful as incentives to work or as rewards for past services. The jobs, construction contracts, and

licenses and other sorts of small chunks of government resources are a small part of the resources available as patronage (distributive policy) by government. The importance of patronage

as a category of policy, or use of the state, can best be conveyed by identifying the practice that gave patronage its name: The feudal lord was patron to the vassals and serfs who

occupied the lord's or baron's or monarch's domain, and these resources were distributed to each dependent individual on a personal, individualized basis, in return for services, loyalty, and reputation for the goodness of the chieftain. The "patron of

the arts" is one of the derivations, seen in the dowager lady or retired philanthropist who distributes his or her resources on a personal basis to deserving artists, performers or other claimants. It is this subdivision of resources and their

distribution on an individualized, personal basis that defines the character of patronage historically and the character of "distributive policy" in the logical scheme of Table 2. Table 2 places this one category in the context of other possible categories of policy, defined logically on the basis of my own conceptualization of the different types of coercion, or "uses of government." Regulatory policy already introduced, is

-9-

also implemented on an individualized basis (see upper axis), but in this case the resources and incentives are not what is being distributed but actually obligations, mainly in the form of rules limiting and restricting individual conduct. Regulatory policy

obviously establishes a relationship between citizen and government far different from the relationship prevailing under conditions of patronage policy. That is, each is a different way

of using government, and therefore each creates the conditions for a very different kind of politics. This is the basis for a

principle guiding my analysis of policy for the past 30 and more years: Policies cause politics.

Two other categories, redistributive and constituent, complete the matrix and exhaust the types of policy governments can produce and the types of politics flowing therefrom. It is

important also to note that this means political systems are not comprised of a single "political process" but are comprised of at least four different political processes, each with its own power structure and political behavior patterns among participants. The four boxes containing the four types of public policy are defined by the two major axes: policies are characterized by

whether the "likelihood of coercion" is remote or immediate (or indirect versus direct). This readily distinguishes the

distributive or patronage policy from the regulatory policy, as shown in the two respective boxes. The second axis looks at

policy in terms of whether the policy seeks to influence conduct

-10-

by working on or through individuals or whether it seeks to influence conduct by manipulating the environment of that conduct or the conditions of its exercise. (Think of micro v. macro.)

For example, on this axis distributive and regulatory policies are in the same dimension -- because both work through the individual (through individual incentives or through individual obligations). The "redistributive" policies can be just as

coercive as the regulatory, but a change in the tax structure or a slight increase or cut in interest rates can seriously alter conduct by altering the conditions of that conduct without ever having to recognize or find out the identity of any individual on whom the impact is influential. Likewise, the creation of new

budgeting methods or central purchasing, or laws having to do with elections or with the re-division of powers among institutions or Branches, are important policies but they are policies concerned with the internal workings of government and how these reforms create new environments for citizens. Then the

linkage from these categories of policy to the most likely political process patterns are visualized on Diagram 2 by the lines running across the matrix to illustrative adjectives outside the matrix. This will be the context and source of criteria for examining and exploring the politics of infrastructure policy. My hope also is that they will help provide a basis for making normative judgments and actual policy recommendations.

-11-

THE POLITICS OF INFRASTRUCTURE POLICY Some Case Studies

New Haven:

It's Not WHO GOVERNS?, Stupid; It's WHAT GOVERNS?

Robert Dahl's classic study of New Haven, Who Governs?, was virtually the birth of the empirically-grounded pluralist theory of politics in America. Pluralist theory describes a special

form of democracy, not directly of the people but one in which power is kept open and relatively decentralized by competition and bargaining among leaders, especially leaders of groups, making for multiple elites, based in pluralities of independent power centers or "nuclei." Governments were conducted, policies

got made, and political equilibrium of sorts was maintained through bargaining. And those bargains between major private

interest groups and other qualified players and public officials were formally inscribed as the public policies that were more likely to serve the public interest than any other realistic alternative. (This is directly inspired by the "invisible hand" Dahl found the motherlode of

dynamic of classical economics.)

pluralist political theory in the actual practices of the city of New Haven and the policies of urban development and redevelopment by carefully studying them for several years during the height of federal aid to urban infrastructure in the 1950s. By the mid-60s, New Haven had spend $790.25 in federal funds

-12-

per capita on urban redevelopment, compared to the average for all cities of $453.51 [Wolfinger, The Politics of Progress, 1974, p. 195]. And the energy of its progress and the placement

decisions in New Haven were being made by a plurastic process centered on the mayor. All this is well-documented by books and But

articles arising out of the best-studied city in America.

the bomb that started all this came not from within the city at all ("as a political system") but from a single decision made by the lobbying efforts of the mayor of New Haven and the governor of Connecticut, concentrating on the federal highway authorities and their Connecticut congressional delegation to add one exit off the new Interstate Highway 95. It came off just adjacent to

an interchange already planned and in construction, and it was designed and built to run directly through the dead center of downtown New Haven, ending abruptly at a dead end intersection with a normal cross-street just a few blocks beyond the downtown. Why? Because the interchange ran through and wiped out the

worst slum in the city, a neighborhood of dilapidated, low-rent flats and shops sprawled out between Yale University/New Haven Common on the one side and Grace-New Haven/Yale University Hospital on the other. Leaving aside the wisdom of that particular piece of infrastructure, its role in driving the New Haven re-development story for its decade as the most admired as well as the most studied city bring severe doubt on the whole theory and practice

-13-

of pluralism in cities.

The whole story of New Haven re-

development could be re-told as a story of "national power structure" with cities as dependent units, far from the autonomous political systems by which they are usually characterized. This is not offered as a reversal or disconfirmation of Dahl's pluralistic heaven, but an amendment: When public works

programs (and other programs too, but especially public works) are devolved from national or state governments, leaving discretion in the hands of city officials as to how to implement the programs and use the grants-in-aid money, the officials can build coalitions around these resources to carry out local plans and objectives they already had but didn't otherwise have the means. Two important points need to be added here. First,

cities are inherently conservative -- in the sense that their obligations under state "police power" are "to maintain the health, safety and morals of the community," largely through keeping different classes, races and ethnic groups apart from each other. Second, the use of development money and discretion

devolved from above is, in consequence, conservative. Conservatives are the best planners because their plans are for maintenance and conservation of existing social values and social structures, not, as with liberals, for their alteration. constitutes Lesson #1, or the moral, of the story: This

When you

commit to a piece of public works, especially if it is

-14-

infrastructure (having a strong paradigmatic element) you have to have a social as well as a construction plan -- or someone else, unauthorized, will use the resources to make their own social plan, usually contrary to the one the planners would have had if they had developed one. This goes well beyond New Haven. All we have to do is look For

at the typical big city, as well as the middle size one.

example, the arterial highways in and around Chicago, built also in the 1950s and 60s, were definitely the engine for much of urban re-development in that city, which came to be called "Negro removal," "slum renewal," and "white and black, shoulder to shoulder, again the working classes." Nationally financed Dan

Ryan Expressway (I-90 and I-94) plus the state-financed University of Illinois/Chicago campus, shoulder to shoulder, wiped out Chicago's largest downtown slum, the Maxwell Street slum. The University of Illinois/Chicago campus is called "the

circle campus" because it was built on lands acquired and cleared in a stretch far beyond the gigantic interchange itself, comprised of concentric circles where north-bound Ryan meets west-bound I-290 (the Eisenhower Expressway). Another East-West

connector had been planned to cut across one of the largest black neighborhoods in Chicago -- south of 63rd Street, Woodlawn, bordering on the University of Chicago; but by the 1960s, when construction and removal were to begin, the all-black Woodlawn Organization had developed sufficient strength and popular

-15-

support to block it.

Chicago is more segregated along race and

class lines after the urban re-development/Interstate Highway era than before.

Iron City: Planners

Another Look at Why Conservatives Make the Best

Iron City is a middle-size southern industrial city, near Birmingham and a small clone of Birmingham.1 What happened to

infrastructure there happened almost everywhere else, but it is easier to see and to document in a smaller city, especially one that was so explicit about its own plan for how it would use the resources it would get from federal programs involving grants-inaid for urban infrastructure. In 1950, 20 percent of Iron City's population was black, but, unlike northern cities, blacks did not live in those concentrated neighborhoods that came to be called black ghettos. Like most southern cities, mainly because of slow general growth and slow and steady black immigration from nearby rural areas, and particularly because so many, especially the women, worked as domestic servants in white households (before the universality of the automobile), white neighborhoods were interlarded with black. "Close quarters" it was often called. This was altogether

stable and comfortable until the whole system of legal This account is drawn entirely from Lowi, The End of Liberalism, 1969, revisited 1979.

1

-16-

segregation came into crisis, and then it became clear to the local elites that there would be no possible way Iron City could keep its public schools racially segregated by drawing school district lines that would pass judicial review or administrative review by the grant givers. The local planners were visionary in

this, because they stepped into the crisis by forming the Iron City Planning Commission in 1951, and by 1952 the Commission had a handsome master plan, in full color, with transparent overlays and all the fancy design that mark professional planning. laid out quite explicitly a five-point plan. It

(1) An all black

neighborhood but with too small a population to warrant proper recreational, school or social services. (2) An all black

neighborhood also with blighted and substandard housing but occupied by people not eligible for relocation in public housing or who personally preferred single-family homes. (3) An area

also of "blighted and depreciating" housing but "growing as the focal point of Negro life." (4) An all black neighborhood

sparsely filled by shacks with outside toilets but strung along the river on prime property slated for civic development. happened also that #1 was located just behind the white neighborhood with the highest assess valued white housing and also abutting the largest all-white junior high school. Area It

designated #2 was located directly behind the central (white) high school. Area #3 was an all-black neighborhood, sparsely

filled by shacks with outside toilets but strung along the river

-17-

on property designated as prime property slated for civic development. Area #4 was "across the tracks;" it was the largest

all-black neighborhood and also "blighted and depreciated" but was "growing as the focal point of Negro life." It happened also

to be located next to the one all-black high school, junior high school and primary school. Area #1 was completely "urban renewed." A regular street

plan replaced the dead-end alleys, and middle-class single-family homes replaced the shacks. This project more than met the

planning criteria of federal urban policy, inasmuch as slums were cleared and a very significant amount of property was returned to the city tax base. The increased white population in the new

area was accommodated by the expansion of the next-door junior high school and the addition of an elementary school with new playgrounds. money. Area #2, directly behind the Central High School, was wiped out and replaced by public housing, all-white. Area #4 was also Urban re-development and community facilities

completely wiped out; part of the cleared land became the site for the new city hall and city jail, beautifully overlooking the river, and the rest was landscaped for "city beautiful." community facilities money. The

Area #3 did indeed expand as "the

focal point of Negro life," with public housing and with singlefamily homes financed by federal public housing grants-in-aid and federal urban re-development grants-in-aid keeping the cost of

-18-

single-family homes and duplexes at rock bottom prices. Thus, the apartheid plan was a complete success. Iron City

had its ghetto and the almost complete racial segregation of the population. And it was all done legally, explicitly, and with In fact it had not been possible without Between 1957 and 1961, when the plan was

federal assistance. federal assistance.

virtually complete, federal grants-in-aid came to almost exactly 20 percent of Iron City's annual government budget. And this

does not count an undetermined amount of federal highway assistance that had contributed to the removal of smaller and separated black neighborhoods that were not part of the original Iron City plan. It also does not count FHA and VA private

financing for the lovely homes built in Area #1 or some of the homes built in the all-black area. It does count the building of

the new all-black auditorium and the church that had been picked up from Area #1 and moved, with the black population, over to Area #3 to join the other focal points of Negro life. Moral to the story: If you want to be sure your city plan

is a success, use the secondary and tertiary effects of infrastructure, and be sure there is plenty of money outside the local tax base.

Death of a Village:

Do Pure Scientists Make Good Planners?

This story took place in the 1960s, and at that time we looked at it as an intimation of the future, because it involved

-19-

pure scientists as planners and builders.

It was a look at the

future because more and more scientists were going to be involved, either as builders and planners themselves or as analysts and consultants to builders who would increasingly need a research and analysis base for any large project, especially one that was likely to be a paradigmatic, infrastructure project. It was clear by the time we finished the research and writing for the book that we were already living our future. Thirty

years and a second edition have passed since then, and we are certainly living our future now.2 The National Accelerator

Laboratory, FermiLab is located on 6800-acre site, 30 miles due west of the center of Chicago on what used to be 71 farms occupied by 71 farm families. It was, until recent years, the

world's largest atom smasher, and it was a proud and comfortable location in DuPage County, one of America's most prosperous counties, near wealthy suburbs and also near mansion and horse country where, at least until recently, people still got together for fox hunts. Our story begins in 1959, when one farm owner decided to sell her 420-acre farm to a developer, who immediately sought permits from the county to subdivide the property and build 100 low-cost single family homes at prices accessible to workingThis account is based entirely on Lowi et al., Poliscide -Big Government, Big Science, Lilliputian Politics (Macmillan, 1976; 2nd ed., University Press of America, 1990).

2

-20-

class people.

All hell broke loose.

This was seen as a tipping

point, because the baby boom growth was in this direction, and many other farmers were caught in a vise: unable to make a

living without an outside job to supplement farm income, and suffering a rate of taxation at suburban rather open-country levels. Every device available to local government was used to

stop the developer, who was already beginning to advertise the new village of Weston, Illinois, for the good, solid working classes. Following some court victories, and the meeting of the

stiff county criteria for access roads, plumbing and sewerage, construction codes, etc., the Weston developers found themselves unable to beat the conspiracy of banks and other private interests to block local financing. The developer persevered,

finding outside financing -- which turned out to be Mafia money, but this only came out later, with the publication of our book. In order to meet the local construction criteria, each Weston home would have to be marketed at $30,000-plus, far above working-class capacity in 1959.3

3

But the county planner knew

And there was still another impediment that would push the Weston home financing upwards: The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veterans Administration (VA) officials refused to provide insured mortgages for Weston homeowners. This is consistent with FHA and VA policy, first to cooperate with local authorities, and second, to refuse to insure home investments in urban slums. Another impediment was the refusal that the county got from the U.S. Post Office to make house-to-house delivery to the Weston homes, thus requiring that nearly a hundred mailboxes would be strung along the county highway, several hundred feet from the entrance to the village.

-21-

that, once Weston got its incorporation, it would have power to carve 3 60-foot lots out of each pair of 90-foot lots, enabling the developers to offer Weston homes well below the regulated county housing market. By 1965, Weston was an operating community, with almost all of their houses occupied and fully financed. It appeared that

the private developers had beaten the gigantic DuPage county government, despite all of its own formidable authority and despite the collateral help it had gotten in conspiracy with local private developers, banks, gentlemen farmers, and the like. But help was on the way. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was

engaged in a nationwide search for the site for what was to be the world's largest atom smasher. Immediately the AEC was

deluged with over 200 proposals from 46 states, and the competition was intense, because the stakes were high: The 200-

billion electronvolt (BeV) accelerator would be a highly desirable "clean industry," whose construction would cost over $1 billion, whose operating needs would lead to the employment of an indeterminate but very large number of quality workers in stable, quality jobs -- not to count the large number of resident scientists and technicians, many of whom were expected to live in that vicinity. On December 15, 1966, Chicagoans learned they would soon be the proud neighbor of the world's largest atom smasher. It was

to be located virtually on top of the village of Weston, whose

-22-

inhabitants had been promised that their homes would be picked up bodily and moved to a nearby location and would become the "service city" for the science installation. The mayor even

arranged for the construction of an enormous billboard sign pointing attention to Weston, the country's first "atomic village." Almost exactly 20 months after the announcement that

the Weston site could be selected by the AEC, no legal trace of the village or the farms remained. National Accelerator

Laboratory (NAL) personnel occupied the village homes and the farmhouses while supervising construction of the underground ring, two miles in diameter. This was the village that was to And it was to

have been moved with all of its occupants intact.

be moved because the villagers had been told that the accelerator ring, for geological reasons, would have to be put directly on top of the village itself. This was a conspiracy to beat all conspiracies. It was a

conspiracy with DuPage county officials at the center, with the State of Illinois Department of Business and Economic Development (DBED) as a key ax-wielder, with Mayor Daley's political troops in Chicago dealing directly with Chicago banks, with Chicago and county newspapers agreeing to have their real estate editors refuse advertisements promoting the Weston development, and several agencies of the U.S. national government, whose enormous largess for "science infrastructure" was being made available at the discretion of the local authorities on the scene.

-23-

What is even more significant is the fact that the scientists -- both the visionary designers of the accelerator, including Cornell's most famous Robert Wilson -- and the science planners at AEC and at the National Academy of Science, and all the other sciences in the mid-West who had sought so hard to bring the great accelerator there instead of losing out once again to the East Coast or the West Coast scientists -- all of these people, one and together, singly and collectively, were totally ignorant of the secondary and tertiary uses to which the accelerator opportunity was being put. Judging from scores of

interviews prior to publication, and almost as many reactions to our book when it was sent directly to a great number of the participants, the scientists never knew what hit them. Professor

Robert Wilson, who had years earlier proposed a much cheaper alternative that could meet most of the needs of the giant atom smasher was, as a consequence, made the designer, supervisor and first director of FermiLab. And this very humane, very

humanistic scientist-poet not only provided for the building of the accelerator at the lowest possible cost, but also engaged in a most enlightened hiring policy, in terms of race as well as class. And since the county had granted the NAL more than twice

as much land as the original specifications required (6800 instead of 3,000 acres, in order to include all the likely farms that would tip over into development), Dr. Wilson dedicated several acres of the surplus property to the construction of a

-24-

model farm to be run by "Farmer Bob," a farm manager with a Ph.D., to help preserve "the only vestige of rural living in this area ...." They even installed a small herd of buffalo on the

land that had been cleared from every vestige of natural rural life. Moral to the story: Scientists, just like highway

developers, tend to be so project-oriented that they say to local planners, in effect, "Give us our toy, but don't tell us how you got it." When the center doesn't plan, the periphery will,

usually with the imposition of local values, no matter how far removed they are from central values. plan, they are socialists. "city fathers." When central planners

When local planners plan, they are

You cannot have a strategic public work, any If you don't make the plan,

public work, without a plan. somebody else will.

With your dough.

Back to the Twelfth Century: Cathedrals

International Airports, the Modern

[In the interest of time and space, this case will be added after the Conference, for the final draft.]

REFLECTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS My reflections have been anticipated in the moral at the end of each of the cases. By the very nature of public works

policies -- especially infrastructure policies, if the

-25-

paradigmatic element is understood to be present -- there will be secondary and tertiary effects. These will always be social and And the social and

political as well as economic and technical.

political will be the most extensive and will involve the largest range of "unanticipated consequences." Infrastructure -- again

by its very nature -- will always be inhabited by local interests, and local interests will be far more intensely pursued than the regional, national, or other broader "public interests." Table 2 is reproduced from Poliscide and, as in the book, it is designed to be generalizable in large part to all large public works projects, especially those involving all three levels of government in the federal system. In fact, the larger the scale

and cost of a public works project, the more likely all the levels of government in the federal system will be involved, with greater money provided from above and more discretion in implementation devolved downward. That is, the greater the

distance from the money provider, the more discretion in the hands of the money distributor. The names of the players will

not be the same as those on Table 2, but the roles and the perspectives flowing from each role remain about the same. Now back to the policy scheme introduced earlier. Putting

this together within the federal system, we are well-advised to attach a label to all public works projects: project can be harmful to your health. Beware: This

Public works policies That

make resources available on a highly disaggregable basis.

-26-

is, they can be subdivided into units and the units can be exchanged, traded and cumulated in a relatively fluid, individualized basis. more. Picture once again the pork barrel. But

As observed earlier, this kind of policy uses government

power in a promotional way, with a minimum of coercion and therefore produces a special relationship between government and citizen. This facilitates in turn a special kind of political

process, one in which a very special kind of coalition prevails: logrolling. Logrolling is a vulgar, slang term for one of the Logrolling can be

fundamental types of political relationship.

defined as an agreement of mutual support between two or more people who have absolutely nothing in common -- except the agreement of mutual support. In contrast, coalitions in the

struggle for regulatory policy are the classic compromise-type coalition in which all participants must make their respective interests known and then examine each others' interests, softening their respective demands until genuine accommodations are reached. Coalitions for redistributive policy also require

mutual knowledge but demand broader knowledge than material interest -- reaching levels of broad social class, socio-economic principle, and, in a word, ideology. Logrolling, the only coalition type concerning us here, is the easiest to form and in many ways the most stable, because participants say to each other, in effect, "You support me on X and I'll support you on any issue -- don't tell me about it; just

-27-

tell me when and how to support you."

John Ferejohn, in his

important book-length study of the politics of "pork barrel policies," written many years after my original characterization, emphasizes the same thing: If a bill calling for improvements in a single district is put [forward], it will not pass, since all the districts must pay and only one will benefit. Consequently, only an omnibus bill proposing expenditures in at least a majority of the districts has a chance of passage.4 But Ferejohn limits his observation to single pieces of traditional "rivers and harbors" type legislation (omnibus) in which dozens of individual projects are added up until a majority of districts are represented. But logrolling coalitions are also

formed across several different projects in several different bills in the same session of the legislature or in later sessions, where payoffs of mutual support are made at later times. In fact, it is one of the major functions of the parties,

or party leaders, to keep records of logrolls and to help facilitate later payoffs. Now I move to the immediate and highly predictable consequences of this kind of coalition: The projects and other

items involved in the logrolling coalition are units of exchange that are intensely concentrated on the projects themselves and on the mutual assistance agreed upon.

4

Little if any room is left

John Ferejohn, Pork Barrel Politics, full citation to be provided.

-28-

for considerations of secondary and tertiary effects and for "public goods" beyond the items involved in the transactions, because these introduce other interests and ideologies that interfere with logrolling. Logrolling coalitions are almost on

principle antagonistic to larger public goods (say, in the realm of regulatory policy or redistributive policy) because the types of coalitions involved in those public goods tend to be incompatible with logrolling coalitions. Now add the other tendency identified above, that in our federal system greater discretion is devolved to the local implementing agencies because greater geographic and juridical distances are involved due to the fact that more intervening layers of delegation are involved. Now, any type of policy --

distributive (patronage), regulatory, or redistributive -- that leaves maximum discretion to the local implementors must leave open, virtually absent, the guidelines and standards that are supposed to keep all implementors relatively close to the law's original intent. In other words, maximum discretion equals When the local implementors have this

minimum rule of law.

degree of discretion, they can convert almost any law, program, project into something close to patronage and therefore to logrolling coalitions, because they can disaggregate the policy into units of decision, and therefore units of logrolling in a logrolling coalition. Go back to Diagram 1 or Diagram 2 and draw

a broad, curving arrow through all four boxes, starting with the

-29-

regulation box and curving round to end with the distributive (or patronage) policy box. I call this the "entropic tendency" in

politics, the tendency of any and all types of politics to deteriorate or drain downward toward the logrolling type of political process that prevails in the distributive or patronage policy category. To reveal the nature and dynamics of this peculiar type of coalition politics is not only to reveal the risk, indeed the danger, to society of the highly compartmentalized commitment to public works projects merely based on a positive cost-benefit analysis. It also provides some insight into ways we may combat

the danger and have our infrastructure without the undue social costs and other unanticipated consequences we always seem to have to endure. We jolly well need a large proportion of the public For the sake of argument, our society Yet, we

works projects proposed.

may well need all the infrastructure projects proposed.

cannot outlaw the narrow-minded logrolling coalitions that form in support of these projects and militate against broader considerations of social good. And we cannot preach our way out

by stressing the goodness of the broader, ecology or justice oriented considerations. The logrolling coalition will always We have to

rollover those humane and philanthropic sentiments.

find a way out that is ruggedly equivalent to the way in, fighting fire with fire. First, it seems to me we have to recognize immediately that

-30-

cost-benefit approaches are a trap.

In the hands of project-

oriented interests and their technologist consultants, it is a means of foreclosing debate, not a route toward enlightened policy. We can move the project away from the project mentality

only by requiring that every project embody a genuine and clear policy -- rule of law -- to govern it. If the origin and the

authorization and financing (all or part) are national, the policy must also be national. (If Americans no longer want a

national government or trust a national government, then let the locals finance and construct their own highways and segregate their own populations without federal help.) And the policy

governing the project must be a rule of law carefully oriented toward governing the secondary and tertiary (and broader spillover) effects of the project. We must require this not only

because real policies embodying real rules of law are necessary if we are ever to improve our chances to attain the goals of sustainable development and social equality. Rules of law are

necessary because we are supposed to be a constitutional democracy. policy. Every public works project is freighted with social

The question is not whether public works should embody a

social policy but who shall make the policy -- the law makers or the local elites. When project designers admit that they should

be governed by the social policies of higher political authorities, they are doing more than behaving responsibly toward their positions. They are also setting limits on the extent to

-31-

which local project recipients can abuse, misuse and misdirect these resources. This involves recognition that policy has to be

a standard of responsible conduct for local authorities that are above and beyond their own immediate manipulation. There is still another advantage to attaching explicit social policies to each and every public works project. larger policy works as a limit on the designers and the congressional budget makers themselves. The introduction of a The

larger social policy changes immediately the type of political process involved, and that is precisely the best way out of the danger of project-oriented decision making. This is the only way

to put an end to such policy barons as Bud Shuster, chairman of the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, who has put his congressional district under about six feet of concrete. Exit: the institutionalization of second thoughts:

Public works projects, even including important infrastructure projects, are distinguished by decisions that embody no rule of conduct, because when each unit is discreet and treated discreetly, this is tantamount to saying that no rule or condition binds any of the recipients. It does not matter much

whether the decision makers are political hacks, career bureaucrats, politically appointed lawyers, members of Congress, or high-energy physicists. Once the patronage policy process is On the other

set in train, the behavior series is predictable.

hand, a drastic and immediate change can be made in the decision

-32-

series and the political process by the introduction of an important public policy that guides and sets limits on the goals and secondary and tertiary effects of the project. For example,

when some Senators from some northeastern states sought to apply civil rights considerations to the selection of the national accelerator site, Illinois Senator Everett Dirksen replied: There are 20 states that have open occupancy laws. There are 30 states that have no such laws. If Congress in its wisdom undertakes at any time to draw that line [applying a civil rights condition to a specific public works project], then I want to say ... that line is going to be firmly drawn, and it is going to be equally firmly held. Since no one at that time wanted advances in civil rights badly enough to put an end to the pork barrel process, they withdrew their efforts to impose a civil rights policy on the accelerator. But it is nevertheless extremely important to set up a process whereby law makers are forced to be explicit about the absence of policies governing projects and the fact that policies ought to govern selected aspects of the impact of the project. And if law

makers recognized honestly that the absence of a governing rule established by them will simply leave open the opportunity for local units to make their own governing policies, perhaps they will be more determined to establish their own policies rather than leave all that to the locals. The public works process is certainly one of the worst processes in the American system from almost any and every

-33-

perspective. law.

It is bad in terms of the absence of the rule of

It is bad in terms of the narrowness with which decision And it is measurably the

makers can allocate public resources.

worst to the extent that it enables locals to make social policies that would be definitively rejected if those policies were put before the public as a referendum. A worthy and pregnant conclusion is the simple proposition that it is the rule that makes the difference. When a policy is

attached to a project, the "public works political process" is immediately transformed. The transformed process is a better one

because it requires more "search behavior" on the part of the specialized agencies, search behavior beyond the immediateness of the project. It imposes -- without of course guaranteeing -- a

more regular and nationally consistent consideration of social issues. And it institutionalizes second thoughts. Let the But give

technologies be decided by technological specialists.

them an institution that provides them with the opportunity for second thoughts.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Plant Vs Filter by Diana WalstadДокумент6 страницPlant Vs Filter by Diana WalstadaachuОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Shades Eq Gloss Large Shade ChartДокумент2 страницыShades Eq Gloss Large Shade ChartmeganОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Eu Clinical TrialДокумент4 страницыEu Clinical TrialAquaОценок пока нет

- Useful Methods in CatiaДокумент30 страницUseful Methods in CatiaNastase Corina100% (2)

- Data Structures and Algorithms SyllabusДокумент9 страницData Structures and Algorithms SyllabusBongbong GalloОценок пока нет

- Wall Panel SystemsДокумент57 страницWall Panel SystemsChrisel DyОценок пока нет

- Teacher'S Individual Plan For Professional Development SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021Документ2 страницыTeacher'S Individual Plan For Professional Development SCHOOL YEAR 2020-2021Diether Mercado Padua100% (8)

- Segmentation Analysis PDFДокумент48 страницSegmentation Analysis PDFreginaxyОценок пока нет

- "Vote Self-Prediction Hardly Predicts Who Will Vote, and Is (Misleadingly) UnbiasedДокумент43 страницы"Vote Self-Prediction Hardly Predicts Who Will Vote, and Is (Misleadingly) UnbiasedreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Segmentation Analysis PDFДокумент48 страницSegmentation Analysis PDFreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Primary Model Predicts Trump Victory PDFДокумент4 страницыPrimary Model Predicts Trump Victory PDFreginaxyОценок пока нет

- A Bayesian Prediction Model For The U.S. Presidential ElectionДокумент25 страницA Bayesian Prediction Model For The U.S. Presidential ElectionreginaxyОценок пока нет

- A Comparison of Forecasting Methods: Fundamentals, Polling, Prediction Markets, and ExpertsДокумент25 страницA Comparison of Forecasting Methods: Fundamentals, Polling, Prediction Markets, and ExpertsreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Handbook June 05Документ264 страницыHandbook June 05Dipal PrajapatiОценок пока нет

- Quality of Government Toward A More Complex de NitionДокумент13 страницQuality of Government Toward A More Complex de NitionreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Forecasting The 2006 National ElectionsДокумент14 страницForecasting The 2006 National ElectionsreginaxyОценок пока нет

- What Small Spatial Scales Are Relevants As Electoral Contexts PDFДокумент15 страницWhat Small Spatial Scales Are Relevants As Electoral Contexts PDFreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Big Data Technologies InfographicДокумент1 страницаBig Data Technologies InfographicreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Does Presidential Rethoric MatterДокумент24 страницыDoes Presidential Rethoric MatterreginaxyОценок пока нет

- The Primacy of Race in The Geography of Income-Based Voting - New Evidence From Public Voting Records PDFДокумент84 страницыThe Primacy of Race in The Geography of Income-Based Voting - New Evidence From Public Voting Records PDFreginaxyОценок пока нет

- A Statistical Scientist Meets A Philosopher of ScienceДокумент12 страницA Statistical Scientist Meets A Philosopher of SciencereginaxyОценок пока нет

- Demystifying Big DataДокумент40 страницDemystifying Big DataMarkus CaroОценок пока нет

- "Blind Retrospection Electoral Responses To Drought, Flu, and SharkДокумент42 страницы"Blind Retrospection Electoral Responses To Drought, Flu, and SharkreginaxyОценок пока нет

- "Blind Retrospection Electoral Responses To Drought, Flu, and SharkДокумент42 страницы"Blind Retrospection Electoral Responses To Drought, Flu, and SharkreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Nonlinear Principal Component Analysis and Related TechniquesДокумент53 страницыNonlinear Principal Component Analysis and Related TechniquesreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Agenda Building As A Comparative Political ProcessДокумент14 страницAgenda Building As A Comparative Political ProcessreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Forecasting Presidential Elections A Comparison of Naive ModelsДокумент14 страницForecasting Presidential Elections A Comparison of Naive ModelsreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Rating The Presidents Washington To ClintonДокумент13 страницRating The Presidents Washington To ClintonreginaxyОценок пока нет

- What Ever Happened To Policy Implementation An Alternative ApproachДокумент26 страницWhat Ever Happened To Policy Implementation An Alternative ApproachreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Where Is The Rally Approval and Trust of The President Cabinet Congress and Government Since September 11Документ7 страницWhere Is The Rally Approval and Trust of The President Cabinet Congress and Government Since September 11reginaxyОценок пока нет

- M&E Systems and The BudgetДокумент8 страницM&E Systems and The BudgetreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Roads Versus SchoolingДокумент24 страницыRoads Versus SchoolingreginaxyОценок пока нет

- Information Values OpinionДокумент24 страницыInformation Values OpinionreginaxyОценок пока нет

- The Rise and Fall of Social ProblemsДокумент27 страницThe Rise and Fall of Social ProblemsreginaxyОценок пока нет

- New Compabloc IMCP0002GДокумент37 страницNew Compabloc IMCP0002GAnie Ekpenyong0% (1)

- Chapter 10 Planetary Atmospheres: Earth and The Other Terrestrial WorldsДокумент27 страницChapter 10 Planetary Atmospheres: Earth and The Other Terrestrial WorldsEdwin ChuenОценок пока нет

- Portfolio Write-UpДокумент4 страницыPortfolio Write-UpJonFromingsОценок пока нет

- Cs Fujitsu SAP Reference Book IPDFДокумент63 страницыCs Fujitsu SAP Reference Book IPDFVijay MindfireОценок пока нет

- Silk Road Ensemble in Chapel HillДокумент1 страницаSilk Road Ensemble in Chapel HillEmil KangОценок пока нет

- D15 Hybrid P1 QPДокумент6 страницD15 Hybrid P1 QPShaameswary AnnadoraiОценок пока нет

- USA Nozzle 01Документ2 страницыUSA Nozzle 01Justin MercadoОценок пока нет

- Name: Mercado, Kath DATE: 01/15 Score: Activity Answer The Following Items On A Separate Sheet of Paper. Show Your Computations. (4 Items X 5 Points)Документ2 страницыName: Mercado, Kath DATE: 01/15 Score: Activity Answer The Following Items On A Separate Sheet of Paper. Show Your Computations. (4 Items X 5 Points)Kathleen MercadoОценок пока нет

- Hailey College of Commerce University of PunjabДокумент12 страницHailey College of Commerce University of PunjabFaryal MunirОценок пока нет

- Lightolier Lytecaster Downlights Catalog 1984Документ68 страницLightolier Lytecaster Downlights Catalog 1984Alan MastersОценок пока нет

- 24 Inch MonitorДокумент10 страниц24 Inch MonitorMihir SaveОценок пока нет

- Ch04Exp PDFДокумент17 страницCh04Exp PDFConstantin PopescuОценок пока нет

- Cash Budget Sharpe Corporation S Projected Sales First 8 Month oДокумент1 страницаCash Budget Sharpe Corporation S Projected Sales First 8 Month oAmit PandeyОценок пока нет

- Comparison of Sic Mosfet and Si IgbtДокумент10 страницComparison of Sic Mosfet and Si IgbtYassir ButtОценок пока нет

- ФО Англ.яз 3клДокумент135 страницФО Англ.яз 3клБакытгуль МендалиеваОценок пока нет

- NIFT GAT Sample Test Paper 1Документ13 страницNIFT GAT Sample Test Paper 1goelОценок пока нет

- CLASS XI (COMPUTER SCIENCE) HALF YEARLY QP Bhopal Region Set-IIДокумент4 страницыCLASS XI (COMPUTER SCIENCE) HALF YEARLY QP Bhopal Region Set-IIDeepika AggarwalОценок пока нет

- Portfolio AdityaДокумент26 страницPortfolio AdityaAditya DisОценок пока нет

- Pepcoding - Coding ContestДокумент2 страницыPepcoding - Coding ContestAjay YadavОценок пока нет

- @InglizEnglish-4000 Essential English Words 6 UzbДокумент193 страницы@InglizEnglish-4000 Essential English Words 6 UzbMaster SmartОценок пока нет

- Development of A Small Solar Thermal PowДокумент10 страницDevelopment of A Small Solar Thermal Powעקיבא אסОценок пока нет

- Thesis Topics in Medicine in Delhi UniversityДокумент8 страницThesis Topics in Medicine in Delhi UniversityBecky Goins100% (2)

- TSC M34PV - TSC M48PV - User Manual - CryoMed - General Purpose - Rev A - EnglishДокумент93 страницыTSC M34PV - TSC M48PV - User Manual - CryoMed - General Purpose - Rev A - EnglishMurielle HeuchonОценок пока нет