Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Lebowitz hellerMarxNeeds2b

Загружено:

tprugИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Lebowitz hellerMarxNeeds2b

Загружено:

tprugАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

REVIEW ARTICLE

HELLER ON MARXS CONCEPT OF NEEDS* Agnes Heller is one of the most prom inent members of a group of Hungarian theorists who were students, associates and friends of Georg Lukcs and whose work has a common emphasis on Marxism as a philosophy of praxis rooted in a positive value judgm ent.1 Hellers book on M arxs theory of needs, which follows a series of separate essays on related themes (some of which are reprinted in a volume on The Humanisation of Socialism),2 should be seen in this par ticular context as an extension of the argum ent that recognition of a normative model (that of communism) in Marx is necessary both for an understanding of Marx and for the existence of a living Marxism. It is far more than a collection and ordering of M arxs scattered com ments on needs; it is, rather, an attem pt at rediscovery of his theorys original m eaning.3 Thus, the central point which Heller makes in this book is that the leitmotif in Marxs view of needs is the concept of radical needs. What are radical needs? Consider what they are not. They are not the per ceived needs of workers for material products. Such material needs certainly exist, but they exist as part of the capitalist structure of needs, a structure produced as an integral part of capitalism. Not only is their being" part of capitalism, but also their realization. In other words, the struggle of workers to attain their material needs is an affirm ation of capital; it does not itself transcend or contain the possibility of tran scending capitalism. T he reason is that these needs reflect the capi talist system. Only needs which do not belong to capitalism, Heller accordingly argues, can in their realization transcend capitalism. Those needs, des ignated as radical needs, are structural features of societies of associated

* Agnes Heller, The Theory of Need in Marx. New York: St. M artin's Press, 1976. $11.95 (cloth). Pp. 135. 1 O thers include Ferenc Feher, Gyorgy M arkus and Mihaly Vajda. See Feher et at., Notes on Lukites' Ontology, Telos (Fall 1976). 2 A ndras H egedus et at.. The Humanisation of Socialism: Writings of the Budapest School (London, 1976). 3 Feher, op. cit., p. 166.

349

350

SCIENCE

AND

SOCIETY

producers. They include the need for community, for hum an relation ships, for labor as an end (lifes prime want), for universality, for free time and free activity, and for the development of personality. They are qualitative needs in contrast to the needs for material (quantita tive) products, which decline relatively in a society of associated pro ducers (as the need to possess" disappears). If radical needs arc part of the structure of a society of associated producers, wrhat are they prior to, or outside of, that society? They are needs, Heller argues, which represent the consciousness of alienation (p. 94), a consciousness o f alienated social and productive relations which is necessarily generated by capitalism. Thus, radical needs (radi cal in that they go to the root, to hum an beings) are produced by capitalism as a collective O ught which can drive people beyond capi talism toward the realization o f a liberated hum an race. For Heller, this is a goal which is attained not by mere political revolution but only by a true revolution, a revolution in everyday life. Radical needs, thus, point to a utopia one which Heller describes as a fertile utopia when measured against present society. As she says elsewhere about Karel Kosik and also about herself in essays on the future of the family, Agnes Heller writes from the perspective of a communist future.4 In interpreting the concept of needs as playing the hidden but principal role in Marxs economic categories (p. 27), Heller offers an im portant alternative to readings of Marx which see the process of change as one of natural laws or as hierarchies of structures indepen dent of the real subjects of the process, determ inate hum an beings. This emphasis on needs of determ inate beings (and consequently their strivings to realize their particular needs) allows a focus on class strug gle as central to an understanding of the laws of motion of specific societies. Unfortunately, Heller does not root her analysis of needs in deter minate hum an beings. Consideration of production and relations of production as the point of departure and the dom inant moment in the relationship between production and needs, which is central to Marxs concept of needs, is missing.5 Hellers stress on the primacy of radical needs over quantitative, material needs flows from her conception of a society of associated producers, a conception in which material needs indeed, the entire realm of material production are matters appro priate to the realm of necessity, not to the realm of freedom (pp. 34,

4 A. Heller, "On the New A dventures o f the Dialectic, Telas (Spring 1977); A. Heller, T he Future of Relations Between the Sexes, in Hegedus, op. (it., p. 27; A. Heller and M. Vajda, Communism and the Family, ibid. 5 K. Marx, Grundrisee (Middlesex, 1973), pp. 94, 99.

T H E CONCEPT OF NEEDS

351

99, 110). Heller thus tends to distort the concept of needs in M arxs work, and instead of analyzing the relation between needs and praxis under real conditions, she presents a critique of all that exists as not truly hum an. Hellers minimization of the importance of quantitative, material needs and her stress on radical needs in her reconstruction of Marxs theory produce problems with respect to the analysis of capitalism and its transcendence. W hat can we say about the struggle of workers to satisfy their quantitative needs? Is this a m ere economism in which the exploited classes generally ask for no more than a better satisfaction of the needs assigned them (p. 97)? As Heller notes, the dem and for higher wages does not in itself transcend the capital/wage labor rela tion. Yet it was Marxs view that this striving for needs which do not themselves go beyond the boundary plays a significant role in the de velopment of the working class itself:

But in reality the proletarians arrive at this unity only through a long process of devel opm ent in which the appeal to their right [equal enjoyment] also plays a part. Inci dentally, this appeal to their right is only a means of making them take shape as they, as a revolutionary, united mass.*

If the struggle for quantitative, material needs plays a part in pro ducing the working class as a class-for-itself, what part is played by radical needs, w'hich, by definition, transcend capitalism? A re revolu tionary workers who attem pt to satisfy their material needs (and to make certain aspects of the ruling classs system o f needs realisable for themselves and, who, furthermore, overturn the existing social order to achieve these goals the bearers of radical needs? No by Hellers definition. While Heller recognizes that the attem pt to obtain satisfaction of material needs can produce the overturning of a social order (a political revolution), she argues that needs that transcend the present in this sense are not radical needs because they transcend only the existing division of needs and not the system o f needs as a whole (p. 97). Who, then, are the bearers of radical needs, which transcend capi talist society and whose bearers are called upon to overthrow capi talism (p. 58)? For Marx, as Heller notes, it was clearly the working class; but not, it seems, for Heller: It does not detract from Marxs greatness that the bearers of these radical needs today are not, or rather not exclusively, the working class (p. 86). While The Theory of Need in Marx is noncommittal on the identifica tion of the bearers of radical needs, elsewhere Heller has been explicit

6 K. Marx and F. Engels, The German Ideology, Collected Works (New York, 1976), Vol. 5, p. 323.

352

SCIENCE

AND SOCIETY

they are students, young people, people in communes, who aban don the refrigerator, car, and prestige-values of their parents; it is only people who consciously organise themselves in communities who can carry through the formation of this new structure of needs.7 Only in the context of a network of pluralistically developed communal life styles is the development of the entire spectrum of qualitative-radical needs .. . thinkable.8 Hellers inclination to identify students and others who presumably reject material needs as the bearers of radical needs flows from the conception of radical needs as rooted in consumption activity rather than in productive activity. Yet it is possible to identify a need (as Marx repeatedly does) whose realization entails the negation of capitalist rela tions and at the same time retain Marxs emphasis on productive activ ity. Such a need, the need of workers to dominate the conditions and results of their labor, clearly expresses Marxs view of the relationship between the working class as bearer of radical needs and the liberation of all humanity. With this alternative formulation of a need whose bearers are called upon to overthrow capitalism, the uncertain relationship be tween radical needs (a$ defined by Heller) and the real process of tran scending capitalism disappears as a problem. For although Heller urges revolutionaries to place radical needs on the agenda, she admits that history has not answered the question of whether capitalist society in fact produces radical needs (p. 95). Indeed, she appears to affirm Marxs view that the abolition of private property (the transcendence of aliena tion) is possible only after the immediate transcendence of capitalism; at one point she says that historical experience up to the present has demonstrated that radical needs do not develop in the masses without an end to the bourgeois way of life and the bourgeois structure.9 While Hellers view of the role of radical needs in the overthrow of capitalism is uncertain, this cannot be said of the importance she attrib utes to them after a political revolution. This indeed is the central point of her argum ent the criticism of actually existing socialism from the perspective of the system of needs in a society of associated producers. It is a criticism both of the continued existence of the capitalist struc ture of needs, of alienate needs, within socialism, and also of perspec tive, of the technocratic world-view, wrhich sees its goal mainly as one of increased satisfaction of everyday needs, the needs to possess.10 In

7 A. Heller, Theory and Practice From the Point of View of Human Needs, in Hegedus, op. cit., p. 74. 8 Ferenc Feher and A. Heller, Forms of F^uality," Telos (Summer 1977), p. 25. 9 A. Heller in Hegedus, op. cit.. pp. 57, 73-4. 10 A. Heller in ibid., p. 44.

T H E CONCEPT OF NEEDS

353

naming and elevating the concept of radical needs, Heller argues that for socialism to truly liberate itself from its antecedent, it is necessary to struggle against alienation and to create institutions which directly em body the realization of radical needs. Even if one accepts the basic point that Marx envisioned a new set of needs within communism and recognizes the importance of the ruthless criticism of all that exists (as Marx advocated), it does not follow that Hellers indictment of the defects of socialism is satisfactory. Writing from the vantage point of a communist future, a society of associated producers, she tends to blur the essential distinction betwreen capitalism and socialism, and between the low*er and upper phases o f communism. A central problem in The Theory of Need in Marx is that Hellers concept of the capitalist structure of needs is faulty. T he capitalist structure of needs, properly defined (in a m anner which perm its a relation between the system of needs and the system of labor), necessar ily includes the needs for objects of productive consumption as well as for those of individual consumption. It must encompass the need of capital for surplus value in addition to the need of w'orkers (and capi talists) to possess use-values. Indeed, it is this form er need, the need of capital to grow, which is the distinctive characteristic o f the capitalist structure of needs; its existence and the associated praxis, the drive to accumulate, produce the non-realization of the needs of workers, as Marxs study of capitalism demonstrated. T he capitalist structure of needs, properly defined, thus includes the needs of capital, the needs of workers, and the relation between the two; it reflects the relations of capitalist production within the sphere of needs. By limiting her defini tion to one aspect (the need to possess material objects), by reducing the whole structure to the need for possession (p. 96), Heller has obscured the differentia specifica of the capitalist structure of needs. Since Heller clearly does not describe socialism as characterized by the need for surplus value as its dom inating principle, it is entirely inappropriate for her to describe the structure of needs within so cialism as capitalist. Even given the continued desire to possess material objects, a structure of needs which does not contain the need of capital for surplus value transcends capitalism and the capitalist structure of needs. T he true object of Hellers critique thus is not capitalism in any sense but its immediate negation, the lower phase o f communism. However, Heller does not attem pt to examine, on the basis of Marxs comments, the model of the lower phase of communism its structure of needs and the relationship between that structure and the sphere of production; rather, her purpose is to delineate the features of a society of associated producers, the first non-alienated society, the

354

SCIENCE

AND

SOCIETY

realm of freedom / from the perspective of the theory of needs (pp. 97, 100). Focusing only on an aspect of the higher phase of com munism, she does not explore the transition from the lower to the higher phase of communism and the role of needs (radical or other wise) in that transition. Indeed, she disavows any attem pt at consider ing transition (p. 100); but this disclaimer is unsatisfactory, given her very concept of radical needs as needs whose bearers are called upon to overthrow' capitalism. Implicitly, Hellers argum ent is that radical needs develop within the lower phase of communism and, as such, become the basis for a movement to a society of associated producers. But why do radical needs develop here? Is this due to the success of the lower phase which, no longer constrained by the needs of capital, expands productive forces and productivity, perm itting a relative saturation of material needs? Heller would deny this, arguing that the focus of the techno cratic world-view on increased satisfaction of everyday needs cannot provide the basis for a natural transition because alienated production produces new needs to possess (p. 52). Is it, then, that radical needs become more intense in this lower phase? T o answ'er this (and, indeed, to choose between possible expla nations for a growth in radical needs) requires consideration of the nature of relations o f production in the lower phase of communism. H ellers failure to explore this aspect means that she does not sec M arxs analysis as the real basis for the development of radical needs in the lower phase of communism. Ultimately, Hellers failure to root her analysis in production indi cates that, despite genuflection to this concept, her analysis starts from consumption rather than production, from hum an essence rather than real living conditions of determ inate hum an beings. Thus, Heller writes as a true socialist and what is lost is M arxs emphasis on the real conditions that transform utopias into genuine movements for social change.11 Despite this general criticism, it is essential to point out that there is much that is worthwhile in this short, provocative and often infuriating book which we have not considered in this attem pt to deal with the main tendency in Hellers argum ent. H er discussion of social needs, of the relation of interests and needs, and in particular her conception of the realm of freedom , are all issues w'hich could be explored at length. And that is a testimonial to the potential wealth of The Theory of Need in Marx. For in addressing herself directly to the question of needs, Heller introduces concepts (such as that of the capitalist struc11 M arx and F.ngels, The German Ideology. T ru e Socialism. passim, but especially p. 518.

T H E CONCEPT OF NEEDS

355

ture of needs and of radical needs) which, explored from the perspec tive of productive activity, are potentially very fruitful. In short, this is a book worth struggling through, one which opens rather than closes the consideration of the theory of need in Marx. Simon Fraser University Burnaby, Canada

MICHAEL A. LEBOW ITZ

Вам также может понравиться

- Classical Theories of Social StratificationДокумент12 страницClassical Theories of Social StratificationkathirОценок пока нет

- Marxist Conflict TheoryДокумент8 страницMarxist Conflict TheoryRolip Saptamaji100% (1)

- Consecration of TalismansДокумент5 страницConsecration of Talismansdancinggoat23100% (1)

- 12 Step Worksheet With QuestionsДокумент26 страниц12 Step Worksheet With QuestionsKristinDaigleОценок пока нет

- VOTOL EMController Manual V2.0Документ18 страницVOTOL EMController Manual V2.0Nandi F. ReyhanОценок пока нет

- Strategic Management SlidesДокумент150 страницStrategic Management SlidesIqra BilalОценок пока нет

- Comparisons and Contrasts Between The Theories of Karl Marx and Max Weber On Social ClassДокумент4 страницыComparisons and Contrasts Between The Theories of Karl Marx and Max Weber On Social ClassEmily Browne100% (1)

- Althusser Contradiction and Over DeterminationДокумент8 страницAlthusser Contradiction and Over DeterminationMatheus de BritoОценок пока нет

- National Interest Waiver Software EngineerДокумент15 страницNational Interest Waiver Software EngineerFaha JavedОценок пока нет

- Branko Horvat, Tekstovi 1959-1996Документ795 страницBranko Horvat, Tekstovi 1959-1996tprugОценок пока нет

- PDS DeltaV SimulateДокумент9 страницPDS DeltaV SimulateJesus JuarezОценок пока нет

- Submitted By: Peter Karl MarxДокумент5 страницSubmitted By: Peter Karl MarxPeter ShimrayОценок пока нет

- Xiaoping Wei, THE INTERPRETATION OF CAPITAL: AN INTERvIEW WITH MICHAEL HEINRICH (WRPE, 2012)Документ21 страницаXiaoping Wei, THE INTERPRETATION OF CAPITAL: AN INTERvIEW WITH MICHAEL HEINRICH (WRPE, 2012)tprugОценок пока нет

- Life and Works of Jose Rizal Modified ModuleДокумент96 страницLife and Works of Jose Rizal Modified ModuleRamos, Queencie R.Оценок пока нет

- Waste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFДокумент11 страницWaste Biorefinery Models Towards Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy Critical Review and Future Perspectives2016bioresource Technology PDFdatinov100% (1)

- Marxism and Literary Theory by Nasrulah MambrolДокумент13 страницMarxism and Literary Theory by Nasrulah MambrolIago TorresОценок пока нет

- The Most Important Concepts of Karl MarxДокумент3 страницыThe Most Important Concepts of Karl MarxGantyala SridharОценок пока нет

- Karl MarxДокумент15 страницKarl MarxJubert NgОценок пока нет

- Marxist Theories of LawДокумент91 страницаMarxist Theories of Lawpablo mgОценок пока нет

- Marxist Conception of HistoryДокумент3 страницыMarxist Conception of HistoryUdhey MannОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx and The Origins of The Social Theory of Class StruggleДокумент51 страницаKarl Marx and The Origins of The Social Theory of Class StruggleFaruque Khan YumkhaibamОценок пока нет

- Barker2013 Marxism and Social MovementsДокумент9 страницBarker2013 Marxism and Social MovementsBruno Rojas SotoОценок пока нет

- Part One Marxism NotesДокумент17 страницPart One Marxism NotesBright MutalemwaОценок пока нет

- Marx SiДокумент51 страницаMarx SiRadha CharpotaОценок пока нет

- THE German Ideology: "As Individuals Express Their Life, So They Are."Документ14 страницTHE German Ideology: "As Individuals Express Their Life, So They Are."Anand YamarthiОценок пока нет

- Class Conflict Theory of Karl Marx: 1.4 Political ScienceДокумент11 страницClass Conflict Theory of Karl Marx: 1.4 Political ScienceYukti ShiwankarОценок пока нет

- Review of Related LiteratureДокумент15 страницReview of Related LiteratureVal ValenceОценок пока нет

- An Unfinished Project: Marx's Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of RightДокумент2 страницыAn Unfinished Project: Marx's Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of RightAlvaro MedinaОценок пока нет

- Title: Alienation and Its Intricate Link To Class Struggle: A Critical Analysis of Marxist ThoughtДокумент9 страницTitle: Alienation and Its Intricate Link To Class Struggle: A Critical Analysis of Marxist Thought22501334namrataranaОценок пока нет

- Hegemony Entry Patrick DoveДокумент19 страницHegemony Entry Patrick DovePatrick DoveОценок пока нет

- Marx and WeberДокумент11 страницMarx and WeberOnur OksanОценок пока нет

- Print WSWS Summary PlusДокумент35 страницPrint WSWS Summary Plusxan30tosОценок пока нет

- Critical Review of Revolution Ideas of Karl MarxДокумент6 страницCritical Review of Revolution Ideas of Karl MarxUmairОценок пока нет

- Notes On Marcuse The Aesthetic DimensionДокумент11 страницNotes On Marcuse The Aesthetic DimensionkurtnewmanОценок пока нет

- Lowy Figuras Do Marxismo WeberianoДокумент11 страницLowy Figuras Do Marxismo WeberianoAriane VelascoОценок пока нет

- Contemporary Literary TheoryДокумент11 страницContemporary Literary TheorysadiasarminОценок пока нет

- Alienation Karl MaxДокумент9 страницAlienation Karl MaxSakina VohraОценок пока нет

- MarxAgainstFreud (Wolfenstein Excerpt)Документ34 страницыMarxAgainstFreud (Wolfenstein Excerpt)Ioannis ChamodrakasОценок пока нет

- Classical Theories of Social StratificationДокумент12 страницClassical Theories of Social StratificationkathirОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx Theory of Alienation and Its R PDFДокумент5 страницKarl Marx Theory of Alienation and Its R PDFBagas Ditya MaulanaОценок пока нет

- The Dialectical SomersaultДокумент12 страницThe Dialectical SomersaultHeatherDelancettОценок пока нет

- Introduction To MarxismДокумент16 страницIntroduction To MarxismJoshua Benedict CoОценок пока нет

- Contribution of Marx and Durkheim To SociologyДокумент10 страницContribution of Marx and Durkheim To SociologyStrikerОценок пока нет

- Class StruggleДокумент12 страницClass StruggleRajesh BethuОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент2 страницыUntitledanrassОценок пока нет

- MARXISMДокумент22 страницыMARXISMJenievieve Sanguenza MedranoОценок пока нет

- 3 - The Social Theorising of Karl Marx (1818-1883)Документ11 страниц3 - The Social Theorising of Karl Marx (1818-1883)Tanya ShereniОценок пока нет

- 65th Anniversary of Marcuse's Reason and RevolutionДокумент15 страниц65th Anniversary of Marcuse's Reason and RevolutionDiego Arrocha ParisОценок пока нет

- Lebowitz FINAL - 1Документ9 страницLebowitz FINAL - 1mlebowitОценок пока нет

- Conflict Perspective 1Документ5 страницConflict Perspective 1Rajnish PrakashОценок пока нет

- DR Sukriti Ghosal: MUC Women's College, BurdwanДокумент34 страницыDR Sukriti Ghosal: MUC Women's College, BurdwanSourav SankiОценок пока нет

- 55-Article Text-4461-1489-10-20210416Документ9 страниц55-Article Text-4461-1489-10-20210416Bonita Marsella azanОценок пока нет

- Socio Sem IДокумент16 страницSocio Sem ISwatantraPandeyОценок пока нет

- Alienation ThesisДокумент81 страницаAlienation ThesisMuir HoustonОценок пока нет

- 2litcrit Prakriti 3429Документ4 страницы2litcrit Prakriti 3429Prakriti KohliОценок пока нет

- Rosen On MarxДокумент23 страницыRosen On Marxchandru675Оценок пока нет

- Sociological TheoryДокумент5 страницSociological TheoryACCIStudentОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx, in Full Karl Heinrich Marx, (Born May 5, 1818, Trier, RhineДокумент4 страницыKarl Marx, in Full Karl Heinrich Marx, (Born May 5, 1818, Trier, RhineCookie CharmОценок пока нет

- Ralf DahrendorfДокумент13 страницRalf DahrendorfMamathaОценок пока нет

- Močnik Restauration-TamásДокумент10 страницMočnik Restauration-TamásRastkoОценок пока нет

- Communist ManifestoДокумент16 страницCommunist ManifestoWisdomОценок пока нет

- AlienationДокумент3 страницыAlienationlifemeansmorewithme100% (1)

- Discuss The Analysis of Class As Given by Karl Marx and Max WeberДокумент5 страницDiscuss The Analysis of Class As Given by Karl Marx and Max Webernerdsonloose0906Оценок пока нет

- Compare and Contrast The Neo - Classical Understanding of The Economy With Marxist Political EconomyДокумент5 страницCompare and Contrast The Neo - Classical Understanding of The Economy With Marxist Political EconomyJay TharappelОценок пока нет

- Sean Sayers: I The Historical Materialist ApproachДокумент24 страницыSean Sayers: I The Historical Materialist ApproachevanОценок пока нет

- Toward Class Consciousness Next Time - Marx and The Working Class by Bertell Ollman PDFДокумент18 страницToward Class Consciousness Next Time - Marx and The Working Class by Bertell Ollman PDFbairagiОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx About Rich PeopleДокумент8 страницKarl Marx About Rich Peopleartur.dregartОценок пока нет

- Karl Marx: Literary Analysis: Philosophical compendiums, #7От EverandKarl Marx: Literary Analysis: Philosophical compendiums, #7Оценок пока нет

- Against The Day - Rebellious Subjects, The Politics of England's 2011 Riots SAQ 2013Документ49 страницAgainst The Day - Rebellious Subjects, The Politics of England's 2011 Riots SAQ 2013tprugОценок пока нет

- The Today Programme and The Banking CrisisДокумент18 страницThe Today Programme and The Banking CrisistprugОценок пока нет

- Paul Smith - Domestic Labour and Marx's Theory of ValueДокумент22 страницыPaul Smith - Domestic Labour and Marx's Theory of Valuetprug100% (2)

- Re-Municipalisation in Europe PSIRU, by Hall, Lobina, Terhorst - Dec 2012Документ29 страницRe-Municipalisation in Europe PSIRU, by Hall, Lobina, Terhorst - Dec 2012tprugОценок пока нет

- Printable Conference Programme, Paris July 2012Документ15 страницPrintable Conference Programme, Paris July 2012tprugОценок пока нет

- Catherine Samary: Plan, Market and Democracy (1988, NSR N.7/8)Документ66 страницCatherine Samary: Plan, Market and Democracy (1988, NSR N.7/8)tprugОценок пока нет

- Hersel Troost LINKE How A Socialisation of The Banks Might LookДокумент21 страницаHersel Troost LINKE How A Socialisation of The Banks Might LooktprugОценок пока нет

- IS-LM: An Explanation - John Hicks - Journal of Post Keynesian Economic - 1980Документ16 страницIS-LM: An Explanation - John Hicks - Journal of Post Keynesian Economic - 1980tprug100% (2)

- Pensions and Class StruggleДокумент26 страницPensions and Class StruggletprugОценок пока нет

- Review of Radical Political Economics Special Issue Economic Democracy, March 2012Документ127 страницReview of Radical Political Economics Special Issue Economic Democracy, March 2012tprugОценок пока нет

- American Intervention in Greece ReviewДокумент13 страницAmerican Intervention in Greece ReviewxeiristosОценок пока нет

- What Is Economics RosaLuxemburg OcrДокумент30 страницWhat Is Economics RosaLuxemburg OcrtprugОценок пока нет

- Rob Johnson: Paradox of Risk AversionДокумент18 страницRob Johnson: Paradox of Risk AversiontprugОценок пока нет

- Martin Hart-Landsberg: ALBA and Cooperative DevelopmentДокумент40 страницMartin Hart-Landsberg: ALBA and Cooperative DevelopmenttprugОценок пока нет

- Open Organizations Poster EnglishДокумент11 страницOpen Organizations Poster EnglishtprugОценок пока нет

- Thimbl Reader March 2012Документ7 страницThimbl Reader March 2012tprugОценок пока нет

- Fisher Productonfunction apervasiveButUnpersuasiveFairytaleДокумент4 страницыFisher Productonfunction apervasiveButUnpersuasiveFairytaletprugОценок пока нет

- KRAS QC12K-4X2500 Hydraulic Shearing Machine With E21S ControllerДокумент3 страницыKRAS QC12K-4X2500 Hydraulic Shearing Machine With E21S ControllerJohan Sneider100% (1)

- Kübler 5800-5820 - enДокумент5 страницKübler 5800-5820 - enpomsarexnbОценок пока нет

- 5.1 Behaviour of Water in Rocks and SoilsДокумент5 страниц5.1 Behaviour of Water in Rocks and SoilsHernandez, Mark Jyssie M.Оценок пока нет

- Bridge Over BrahmaputraДокумент38 страницBridge Over BrahmaputraRahul DevОценок пока нет

- (Gray Meyer) Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits 5th CroppedДокумент60 страниц(Gray Meyer) Analysis and Design of Analog Integrated Circuits 5th CroppedvishalwinsОценок пока нет

- Church and Community Mobilization (CCM)Документ15 страницChurch and Community Mobilization (CCM)FreethinkerTianОценок пока нет

- Accessoryd-2020-07-31-185359.ips 2Документ20 страницAccessoryd-2020-07-31-185359.ips 2Richard GarciaОценок пока нет

- Core CompetenciesДокумент3 страницыCore Competenciesapi-521620733Оценок пока нет

- Marking Scheme For Term 2 Trial Exam, STPM 2019 (Gbs Melaka) Section A (45 Marks)Документ7 страницMarking Scheme For Term 2 Trial Exam, STPM 2019 (Gbs Melaka) Section A (45 Marks)Michelles JimОценок пока нет

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFДокумент12 страницEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFSiphoОценок пока нет

- Installation Instructions INI Luma Gen2Документ21 страницаInstallation Instructions INI Luma Gen2John Kim CarandangОценок пока нет

- Atmel 46003 SE M90E32AS DatasheetДокумент84 страницыAtmel 46003 SE M90E32AS DatasheetNagarajОценок пока нет

- TM Mic Opmaint EngДокумент186 страницTM Mic Opmaint Engkisedi2001100% (2)

- Cap1 - Engineering in TimeДокумент12 страницCap1 - Engineering in TimeHair Lopez100% (1)

- Abnt NBR 16868 1 Alvenaria Estrutural ProjetoДокумент77 страницAbnt NBR 16868 1 Alvenaria Estrutural ProjetoGIOVANNI BRUNO COELHO DE PAULAОценок пока нет

- Spectroscopic Methods For Determination of DexketoprofenДокумент8 страницSpectroscopic Methods For Determination of DexketoprofenManuel VanegasОценок пока нет

- Engineering Ethics in Practice ShorterДокумент79 страницEngineering Ethics in Practice ShorterPrashanta NaikОценок пока нет

- Determinant of Nurses' Response Time in Emergency Department When Taking Care of A PatientДокумент9 страницDeterminant of Nurses' Response Time in Emergency Department When Taking Care of A PatientRuly AryaОценок пока нет

- Đề Tuyển Sinh Lớp 10 Môn Tiếng AnhДокумент11 страницĐề Tuyển Sinh Lớp 10 Môn Tiếng AnhTrangОценок пока нет

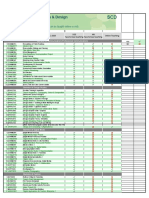

- SCD Course List in Sem 2.2020 (FTF or Online) (Updated 02 July 2020)Документ2 страницыSCD Course List in Sem 2.2020 (FTF or Online) (Updated 02 July 2020)Nguyễn Hồng AnhОценок пока нет

- Importance of Porosity - Permeability Relationship in Sandstone Petrophysical PropertiesДокумент61 страницаImportance of Porosity - Permeability Relationship in Sandstone Petrophysical PropertiesjrtnОценок пока нет

- Installation 59TP6A 08SIДокумент92 страницыInstallation 59TP6A 08SIHenry SmithОценок пока нет