Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Heart Failure

Загружено:

spicychips7Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Heart Failure

Загружено:

spicychips7Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

HEART FAILURE Definition - the state that develops when the heart cannot maintain an adequate cardiac output

or can do so only at the expense of an elevated filling pressure In practice, heart failure may be diagnosed whenever a patient with significant heart disease develops the signs or symptoms of a low cardiac output, pulmonary congestion or systemic venous congestion. Pathophysiology Cardiac output is a function of the preload (the volume and pressure of blood in the ventricle at the end of diastole), the afterload (the volume and pressure of blood in the ventricle during systole) and myocardial contractility. In patients without valvular disease, the primary abnormality in heart failure is impairment of ventricular function leading to a fall in cardiac output. his activates counter-regulatory neurohormonal mechanisms that in normal physiological circumstances would support cardiac function, but in the setting of impaired ventricular function can lead to a deleterious increase in both afterload and preload.

!timulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system leads to vasoconstriction, salt and water retention, and sympathetic activation mediated by angiotensin II, which is a potent constrictor of arterioles both in the "idney and systemic circulation #ctivation of the sympathetic nervous system may initially maintain cardiac output through an increase in myocardial contractility, heart rate and peripheral

vasoconstriction. $owever, prolonged sympathetic stimulation leads to cardiac myocyte apoptosis, hypertrophy and focal myocardial necrosis !alt and water retention is promoted by the release of aldosterone, endothelin (a potent vasoconstrictor peptide with mar"ed effects on the renal vasculature) and, in severe heart failure, antidiuretic hormone (#%$). &atriuretic peptides are released from the atria in response to atrial stretch, and act as physiological antagonists to the fluid-conserving effect of aldosterone. # vicious circle may be established because any additional fall in cardiac output will cause further neurohormonal activation and increasing peripheral vascular resistance. he rate of change of intraventricular pressure (dp'dt) is depressed, with reduced velocity of myocardial fibre shortening and tension development, in patients with heart failure

Types of heart failure A) Left, right and bi entri!ular heart failure Left-sided heart failure- here is a reduction in the left ventricular output and'or an increase in the left atrial or pulmonary venous pressure.e.g mitral stenosis, () Right-sided heart failure. here is a reduction in right ventricular output for any given right atrial pressure e.g chronic lung disease (cor pulmonale), multiple pulmonary emboli and pulmonary valvular stenosis. Biventricular heart failure-e.g dilated cardiomyopathy or ischaemic heart disease ") Diastoli! and systoli! dysfun!tion #ystoli! failure* inability of the ventricle to contract normally, with symptoms resulting from inadequate cardiac output .+,ection fraction ./0 e.g dilated cardiomyopathy, ischaemic heart disease

Diastoli! failure* inability of the ventricle to relax and fill normally, with symptoms from elevated filling pressures .+,ection fraction 1 2/0 e.g hypertension, ischaemic heart disease !ystolic and diastolic dysfunction often coexist, particularly in patients with coronary artery disease. $) A!ute and !hroni! heart failure A!ute heart failure develops following massive myocardial infarction or valve rupture. In acute failure, sudden reduction in cardiac output leads to hypotension without peripheral oedema $hroni! heart failure is seen in slowly progressive valvular heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy and systemic hypertension. in chronic heart failure blood pressure is well maintained but there is oedema over the legs. D) Lo%&output ersus high&output HF Lo%&output HF* cardiac output at rest - 3.3 4'min per m3 (lower limit of normal) and fails to increase normally with exertion e.g myocardial infarction ((I), dilated cardiomyopathy High&output HF* cardiac output 1 5.2 4'min per m3 or upper limit of normal.e.g hyperthyroidism, anemia, pregnancy, arteriovenous fistulas, beriberi, and 6aget7s diseas Pre!ipitating !auses of $$F (yocardial ischaemia or infarction Intercurrent illness, e.g. infection #rrhythmia, e.g. atrial fibrillation Inappropriate reduction of therapy #dministration of a drug with negative inotropic properties (e.g. 8-bloc"er) or fluid-retaining properties (e.g. non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids) 6ulmonary embolism Conditions associated with increased metabolic demand, e.g. pregnancy, thyrotoxicosis, anaemia Intravenous fluid overload, e.g. post-operative i.v. infusion $lini!al features A) #y'pto's () Left heart failure %yspnea with exertion (early) or at rest (late) 9rthopnea %yspnea when recumbent: relief with sitting upright or use of several pillows 6aroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea -#ttac"s of severe shortness of breath and coughing at night: usually awa"ens patient Coughing and whee;ing often persist even with sitting upright.

Cardiac asthma* nocturnal dyspnea, whee;ing and cough due to bronchospasm <atigue and wea"ness )) Right heart failure #bdominal symptoms -#norexia ,&ausea ,#bdominal pain and fullness *)+thers Cerebral symptoms -#ltered mental status due to reduced cerebral perfusion &octuria 6atients with chronic heart failure commonly experience a relapsing and remitting course, with periods of stability and episodes of decompensation leading to worsening symptoms that may necessitate hospitali;ation he clinical picture depends on the nature of the underlying heart disease, the type of heart failure that it has evo"ed, and the neural and endocrine changes that have developed Chronic heart failure is sometimes associated with mar"ed weight loss (cardiac cachexia) caused by a combination of anorexia and impaired absorption due to gastrointestinal congestion: poor tissue perfusion due to a low cardiac output: and s"eletal muscle atrophy due to immobility. Physi!al findings a) ,eneral e-a'ination 4ower-extremity edema =aundice peripheral cyanosis of nails and lips Cold hands and feet Cardiac cachexia 6ulsus alternans -)egular rhythm with alternation in strength of peripheral pulses (ost common in cardiomyopathy, hypertensive, and ischemic heart disease b)$.# )aised =>6, positive abdomino-,ugular reflux Cardiac enlargement (apex beat shifted down and out) )> hypertrophy seen as left parasternal and epigastric pulsation #uscultation - I sound variable, pulmonary component of II sound loud, III and I> sounds may be audible <eatures of primary heart diseases can be seen !) Respiratory syste' ?asal crepitations ?ilateral pelural effusion right 1 left #bdomen enlarged tender liver ascites

$o'pli!ations Renal failure is caused by poor renal perfusion due to a low cardiac output and may be exacerbated by diuretic therapy, #C+ inhibitors and angiotensin receptor bloc"ers. Hypokalaemia may be the result of treatment with potassium-losing diuretics or hyperaldosteronism caused by activation of the renin-angiotensin system and impaired aldosterone metabolism due to hepatic congestion. (ost of the body@s potassium is intracellular and there may be substantial depletion of potassium stores, even when the plasma potassium concentration is in the normal range. Hyperkalaemia may be due to the effects of drug treatment, particularly the combination of angiotensin-converting en;yme (#C+) inhibitors and spironolactone (which both promote potassium retention), and renal dysfunction. Hyponatraemia is a feature of severe heart failure and may be caused by diuretic therapy, inappropriate water retention due to high #%$ secretion, or failure of the cell membrane ion pump. It is a poor prognostic sign, Impaired liver function is caused by hepatic venous congestion and poor arterial perfusion, which frequently cause mild ,aundice and abnormal liver function tests: reduced synthesis of clotting factors may ma"e anticoagulant control difficult. Thromboembolism. %eep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism may occur due to the effects of a low cardiac output and enforced immobility, whereas systemic emboli may be related to arrhythmias, atrial flutter or fibrillation, or intracardiac thrombus complicating conditions such as mitral stenosis or 4> aneurysm. Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias are very common and may be related to electrolyte changes (e.g. hypo"alaemia, hypomagnesaemia), the underlying structural heart disease, and the pro-arrhythmic effects of increased circulating catecholamines and some drugs (e.g. digoxin). !udden death occurs in up to 2/0 of patients with heart failure and is often due to a ventricular arrhythmia. In estigations a) To identify !o'pli!ations +lectrolytes $ypo"alemia from thia;ide diuretics $yper"alemia from potassium-retaining diuretics %ilutional hyponatremia in late $< )enal function -6rerenal a;otemia Arinalysis -#lbuminuria 4iver function testing $epatic en;ymes: frequently elevated +levated direct and indirect bilirubin level (late finding) b) Diagnosis and etiology ?&6 measurement-1 3// pg'm4 supports diagnosis ,- ./ pg'm4 rarely seen in $<

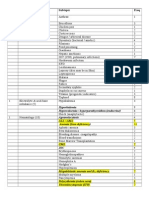

+CB -#ids in determining etiology: e.g. abnormal C waves in old (I, left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension chest D-ray cardiomegaly pulmonary congestion abnormal distension of the upper lobe pulmonary veins- rise in pulmonary venous pressure from left-sided cardiac failure interstitial oedema causes thic"ened interlobular septa and dilated lymphatics. hese are evident as hori;ontal lines in the costophrenic angles (septal or @Eerley ?@ lines) 3-dimensional echocardiography with %oppler flow o determine underlying causes o assess severity of ventricular systolic and'or diastolic dysfunction, valvular dysfunction Cuestion diagnosis if all cardiac chambers normal in volume, shortening and wall thic"ness Fra'ingha' !riteria for diagnosis of !ongesti e heart failure /$HF) o establish a clinical diagnosis of C$< by these criteria, at least F ma,or and 3 minor criteria are required. 0a1or !riteria 6aroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea &ec" vein distention )ales Cardiomegaly #cute pulmonary edema !5 gallop Increased venous pressure 6ositive hepato,ugular reflux 0inor !riteria +xtremity edema &ight cough %yspnea on exertion $epatomegaly 6leural effusion >ital capacity reduced by one-third from normal achycardia (G F3/ beats'min) 0a1or or 'inor !riterion Height loss G ..2 "g over 2 days of treatment

#tages of heat failure #tage A #t high ris" for $<, but no evident structural heart disease or symptoms of $< +xamples $ypertension, Coronary artery disease ,%iabetes mellitus #tage " !tructural heart disease without symptoms of $< +xamples -6revious (I ,4eft ventricular systolic dysfunction, as in longstanding hypertension ,#symptomatic valvular disease ,%ilated, hypertrophic, or restrictive cardiomyopathy #tage $ !tructural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of $< li"e !hortness of breath ,<atigue ,)educed exercise tolerance #tage D )efractory $< requiring speciali;ed interventions (ar"ed symptoms at rest despite maximal medical therapy (e.g., recurrent hospitali;ations or unable to be safely discharged from hospital without speciali;ed interventions) 0anage'ent he ideal approach would be to treat the underlying cause, e.g. control systemic hypertension, surgical correction of valvular defects, treatment of I$%. ,eneral 'easures reat hypertension. reat lipid disorders. +ncourage smo"ing cessation. %iscourage alcohol inta"e and illicit drug use. )ecommend influen;a and pneumococcal vaccines. #chieve optimal weight. #ctivity

)egular isotonic exercise in compensated $< In moderately severe chronic $<* additional rest on wee"end, scheduled naps or rest periods, avoidance of strenuous exertion #void temperature extremes and tiring trips. Diet )educe sodium inta"e (normal diet contains IJF/ g of sodium daily) 4ate in course* often, both sodium and water inta"e must be restricted Drug therapy Cardiac function can be improved by increasing contractility, optimising preload or decreasing afterload %rugs that reduce preload are most appropriate in patients with high end-diastolic filling pressures and evidence of pulmonary or systemic venous congestion (bac"ward failure). %rugs that reduce afterload or increase myocardial contractility are more useful in patients with signs and symptoms of a low cardiac output Thia2ides Indications Ase thia;ides alone in mild !tage C $< and in combination with other diuretics in late, severe !tage C $< or !tage % !ide effects $ypo"alemia $yponatremia (etabolic al"alosis !pecific agents $ydrochlorothia;ide -%osage* 32 mg'd to 32 mg qid Chlorthalidone %osage* 2/JF// mg'd Loop diureti!s Indications for loop diuretics #ll forms of $<, particularly in patients with severe or refractory $< and pulmonary edema !ide effects (etabolic al"alosis $ypo"alemia $yperuricemia !pecific drugs Furosemide -initial dose, 3/ mg (maximum, K/ mg) Torsemide -initial dose, 2 mg (maximum, 3/ mg) +ther diureti!s Metolazone %osage* 3.2 mg FJ3 times daily (maximum, F/ mg'd) #ctions and indications similar to thia;ides

Spironolactone -potassium-sparing diuretics %ose* F3.2 to 32 mg'd: max* 32 mg twice daily Ase with loop diuretic Hea" diuretic, but has been shown to prolong life in !tage C $< !ide effects* $yper"alemia ,Bynecomastia Contraindications - 6otassium level 1 2 mmol'4 ,)enal failure A$E inhibitors #C+ inhibitors have a central role in prevention and treatment of $< at all stages. Contraindications - hypotensive, pregnant, renal failure, hyper"alemia !ide effects -Cough ,renal failure, hyper"alemia, #ngioneurotic edema , eratogenic effects in first trimester !pecific agents +nalapril maleate - 3.2 mg bid (maximum, F/J3/ mg bid) Lisinopril -Initial dosage* 3.2J2./ mg'd (maximum, 3/J./ mg'd) Ramipril -Initial dosage* F.32J3.2 mg'd (maximum, F/ mg'd) Angiotensin re!eptor blo!3ers Indications -Intolerance to #C+ inhibitors !pecific agents Losartan- Initial dosage, 32 mg qd: target dosage, 2/ mg bid Valsartan -Initial dosage, ./ mg bid: target dose, FI/ mg bid Candesartan -Initial dosage, . mg qd, target dose, 53 mg qd "eta blo!3ers Indications for beta bloc"ers* patients in !tage C $< !tabili;e first with #C+ inhibitor, diuretics, and possibly digoxin. ?egin with low doses.9bserve closely for hypotension, bradycardia, and worsening $<. Contraindications - $ypotension ,!evere fluid overload ,!inus bradycardia #trioventricular bloc" ,?ronchospastic disorders !pecific agents Carvedilol -Initial dosage, 5.F32 mg bid (maximum, 32J2/ mg bid) (etoprolol C)'D4 -Initial dosage, F3.2J32 mg'd (maximum, 3// mg'd) Digo-in Indications for digoxin !ystolic $< complicated by atrial flutter and fibrillation and rapid ventricular rate !ystolic $< and sinus rhythm )educes symptoms of $< and need for hospitali;ation 9ral dosage* /.2/ mg'd for 3J5 days, then /.F32 mg every other day to /.32 mg'd (maximum, /.2/ mg'd to avoid toxic effects) Digitalis into-i!ation )is" factors for complication #dvanced age ,$ypo"alemia ,)enal insufficiency !igns and symptoms

#norexia ,&ausea and vomiting ,Bynecomastia %elirium (ost frequent disturbances of cardiac rhythm &onparoxysmal atrial tachycardia and'or variable atrioventricular bloc" >entricular premature beats, bigeminy >entricular tachycardia or rarely ventricular fibrillation reatment %iscontinue digoxin therapy. 8-adrenoceptor bloc"er or lidocaine 9ral potassium replacement (if hypo"alemic) <ab fragments of purified, intact digitalis antibodies (if life threatening) +ther asodilators Indications Chronic $< with systemic vasoconstriction despite #C+ inhibitor therapy !pecific agents Isosorbide dinitrate Initial dosage, F/ mg tid daily (maximum, K/ mg tid) !ublingual isosorbide %osage* 3.2 mg as needed or before exercise to decrease dyspnea Hydralazine Initial dosage, 32 mg tid (maximum, F2/ mg qid) Anti!oagulants Warfarin Indications !evere $< $< and #trial fibrillation 6revious venous thrombosis 6ulmonary or systemic emboli A'iodarone $is is a potent anti-arrhythmic drug which has little negative inotropic effect and may be valuable in patients with poor left ventricular function It is only effective in the treatment of symptomatic arrhythmias, and should not be used as a preventative agent in the asymptomatic I'plantable !ardia! defibrillators and resy!hronisation therapy 6atients with symptomatic ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure have a very poor prognosis. Irrespective of their response to anti-arrhythmic drug therapy, all should be considered for implantation of a cardiac defibrillator In patients with mar"ed intraventricular conduction delay, prolonged depolarisation may lead to uncoordinated left ventricular contraction.

Cardiac )esynchroni;ation herapy (C) ) in combination with stable optimal medical therapy, may help the lower chambers of the heart beat together and improve the heart@s ability to supply blood and oxygen to the body C) is designed to help the two lower heart chambers, the right and left ventricles, beat at the same time in a normal sequence treating ventricular dysynchrony. C) is delivered as tiny electrical pulses to the right and left ventricles through three or four leads (soft insulated wires) that are inserted through the veins to the heart. $ere, both the left and right ventricles are paced simultaneously in an attempt to generate a more coordinated left ventricular contraction and improve cardiac output. Re as!ularisation Coronary artery bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention may improve function in areas of the myocardium that are @hibernating@ because of inadequate blood supply. Heart transplantation Cardiac transplantation is an established and very successful form of treatment for patients with intractable heart failure. Coronary artery disease and dilated cardiomyopathy are the most common indications. he use of transplantation is limited by the availability of donor hearts so it is generally reserved for young patients with severe symptoms Conventional heart transplantation is contraindicated in patients with pulmonary vascular disease due to long-standing left heart failure, complex congenital heart disease (e.g. +isenmenger@s syndrome) or primary pulmonary hypertension, because the right ventricle of the donor heart may fail in the face of increased pulmonary vascular resistance. $owever, heart-lung transplantation can be successful for patients with +isenmenger@s syndrome. 4ung transplantation has been used for primary pulmonary hypertension .entri!ular assist de i!es ?ecause of the limited supply of donor organs, ventricular assist devices (>#%s) have been employed as a bridge to cardiac transplantation, or more recently as potential long-term or @destination@ therapy. hey assist cardiac output by using a roller, centrifugal or pulsatile pump that, in some cases, is implantable and portable. hese devices withdraw blood through cannulae inserted in the atria or ventricular apex and pump it into the pulmonary artery or aorta. >#%s are designed not only to unload the ventricles but also to provide support to the pulmonary and systemic circulations. heir more widespread application is limited by high complication rates (haemorrhage, systemic embolism, infection, neurological and renal sequelae) Re!o''ended therapy, by disease stage #tage A reat hypertension.

6rescribe angiotensin-converting en;yme (#C+) inhibition, especially in hypertension +ncourage smo"ing cessation. reat lipid disorders. +ncourage regular exercise. %iscourage alcohol inta"e and illicit drug use. #tage " #ll measures under !tage # #dd beta-bloc"er. #tage $ #ll measures under stages # and ? #dd diuretic. #dd digitalis in systolic $<. #dd spironalactone. )estrict dietary salt to - 3 g'd (eliminate salt-rich foods and added salt in coo"ing or at table) #tage D #ll measures under !tages #, ?, and C %ietary salt restriction to - F g'd (echanical assist devices $eart transplantation Continuous intravenous inotropic infusions for palliation (does not prolong life)

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- E RacerДокумент17 страницE Racerspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Movement DisordersДокумент6 страницMovement Disordersspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Essential Hypertension ManagementДокумент5 страницEssential Hypertension Managementspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- EncephalitisДокумент4 страницыEncephalitisspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- MeningitisДокумент6 страницMeningitisspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Introduction To NeurologyДокумент6 страницIntroduction To Neurologyspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Neuromuscular Junction Disorders: Applied AnatomyДокумент6 страницNeuromuscular Junction Disorders: Applied Anatomyspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Diabetes Mellitus 1Документ7 страницDiabetes Mellitus 1spicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Class StartersДокумент1 страницаClass Startersspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Diabetes Insipidus (Di) : Etiology and ClassificationДокумент6 страницDiabetes Insipidus (Di) : Etiology and Classificationspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Thyroid Disorders: Physiology of Thyroid HarmonesДокумент68 страницThyroid Disorders: Physiology of Thyroid Harmonesspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Surgery Paper 1 Topic Frequency: Eneral UrgeryДокумент3 страницыSurgery Paper 1 Topic Frequency: Eneral Urgeryspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- HypoglycemiaДокумент3 страницыHypoglycemiaspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Adrenal Glands and Addison'sДокумент6 страницAdrenal Glands and Addison'sspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Paper Topic (Marks) Subtopic Freq: Hyperkalemia Hypercalcemia / Hyperparathyroidism (Endocrine) Agranulocytosis All / AmlДокумент5 страницPaper Topic (Marks) Subtopic Freq: Hyperkalemia Hypercalcemia / Hyperparathyroidism (Endocrine) Agranulocytosis All / Amlspicychips7Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Etiology, Classification and Clinical Approach: EndophthalmitisДокумент42 страницыEtiology, Classification and Clinical Approach: EndophthalmitisHieLdaJanuariaОценок пока нет

- List of Philhealth Accredited Level 3 Hospital As of October 31, 2019Документ35 страницList of Philhealth Accredited Level 3 Hospital As of October 31, 2019Lex CatОценок пока нет

- Amnesia ExplanationДокумент2 страницыAmnesia ExplanationMuslim NugrahaОценок пока нет

- NMSRC Sample Research PaperДокумент4 страницыNMSRC Sample Research Paperjemma chayocasОценок пока нет

- GBS Source 1Документ4 страницыGBS Source 1PJHG50% (2)

- Egypt Biosimilar Guidline Biologicals RegistrationДокумент54 страницыEgypt Biosimilar Guidline Biologicals Registrationshivani hiremathОценок пока нет

- Pathophysiology of RHDДокумент4 страницыPathophysiology of RHDshmily_0810Оценок пока нет

- Medical Questionnaire: To Be Filled by Attending PhysicianДокумент3 страницыMedical Questionnaire: To Be Filled by Attending PhysiciansusomОценок пока нет

- Heart Block and Their Best Treatment in Homeopathy - Bashir Mahmud ElliasДокумент13 страницHeart Block and Their Best Treatment in Homeopathy - Bashir Mahmud ElliasBashir Mahmud Ellias50% (2)

- Pulse OximeterДокумент13 страницPulse Oximeteramanuel waleluОценок пока нет

- Euros Core OrgДокумент6 страницEuros Core OrgClaudio Walter VidelaОценок пока нет

- Seminar On Shock: IndexДокумент37 страницSeminar On Shock: IndexGayathri R100% (1)

- Urinary Tract Infection and Bacteriuria in PregnancyДокумент14 страницUrinary Tract Infection and Bacteriuria in PregnancyAbby QCОценок пока нет

- Fracture Blowout OrbitalДокумент6 страницFracture Blowout OrbitalMasitha RahmawatiОценок пока нет

- National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011: Diabetes Affects 25.8 Million People 8.3% of The U.S. PopulationДокумент12 страницNational Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011: Diabetes Affects 25.8 Million People 8.3% of The U.S. PopulationAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGОценок пока нет

- Four-Month Rifapentine Regimens With or Without Moxifloxacin For TuberculosisДокумент14 страницFour-Month Rifapentine Regimens With or Without Moxifloxacin For TuberculosisyanaОценок пока нет

- So My Cat Has Chronic Kidney DiseaseДокумент2 страницыSo My Cat Has Chronic Kidney DiseaseNur Alisya Hasnul HadiОценок пока нет

- Infection Control in ORДокумент10 страницInfection Control in ORaaminah tariqОценок пока нет

- The EBC 46 Cancer TreatmentДокумент9 страницThe EBC 46 Cancer TreatmentAnimefan TheoОценок пока нет

- Barksy - The Paradox of Health PDFДокумент5 страницBarksy - The Paradox of Health PDFdani_g_1987Оценок пока нет

- The Open Brow LiftДокумент8 страницThe Open Brow LiftdoctorbanОценок пока нет

- 2018 Urinary Tract Infections in ChildrenДокумент12 страниц2018 Urinary Tract Infections in ChildrenYudit Arenita100% (1)

- Serosal Appendicitis: Incidence, Causes and Clinical SignificanceДокумент3 страницыSerosal Appendicitis: Incidence, Causes and Clinical SignificancenaufalrosarОценок пока нет

- Carboplatin MonographДокумент9 страницCarboplatin Monographmerkuri100% (1)

- Ipd - Kelas Ac - Kad Dan Hhs - DR - DR.K Heri Nugroho HS, SP - PD, K-EmdДокумент51 страницаIpd - Kelas Ac - Kad Dan Hhs - DR - DR.K Heri Nugroho HS, SP - PD, K-EmdTeresia MaharaniОценок пока нет

- PHARMACOLOGYДокумент44 страницыPHARMACOLOGYshruti sangwan100% (1)

- Intestinal Amoebiasis CSДокумент34 страницыIntestinal Amoebiasis CSabigailxDОценок пока нет

- Serious Adverse Events of Special Interest Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination in Randomized Trials in AdultsДокумент9 страницSerious Adverse Events of Special Interest Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination in Randomized Trials in AdultsLilianneОценок пока нет

- MagnecalmfactsheetДокумент5 страницMagnecalmfactsheetKeith TippeyОценок пока нет

- Phenylketonuria PkuДокумент8 страницPhenylketonuria Pkuapi-426734065Оценок пока нет