Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Marks-Manship Bullshit

Загружено:

ksat909729Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Marks-Manship Bullshit

Загружено:

ksat909729Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Marks-manship bullshit

Some thoughts about what marks represent in education By Chia Wei I am barely a few months into being a teacher and the perversion of marks has me reeling in disgust. Its less the disgust against the idea of marks, but rather what they stand for in the current education system. In the present tertiary education, students fawn and obsess over the idea of having bonus marks and choice -based assessments; and groan over the idea of projects, assignments and essay-based assessments. Academic departments furl up their brows thinking about moderating scores to fit into a nice bell curve, with talks about pass rates, turnovers,and student feedback. That has triggered a chain of thoughts about the current system of assessment, and the representation of marks and grades.

Let us first examine what do marks represent:

What does it mean if you have scored 75 out of 100 in say, MECH111 Mechanics? Ideally, it means that you have achieved roughly a 75% mastery of what the course needs you to know and apply in this subjectincluding objectives such as calculation, problem solving, and practical application of said knowledge. It is usually composed of a final exam, usually a test of knowledge, and project and assignments that could assess the course objectives that is

relevant to the application of such knowledge. The individual marks of the component should thus correspond to an assessment of the skill or knowledge of the person, and the composite grade a weighted average of these components. If and when an external party should ask about the grade (say in this case 75%), the grade should thus give an approximation of the skill and knowledge of the person. A person that obtained a High Distinction, or an A+/A8, should indicate that the person understands and is able to apply proficiently such knowledge to problems in the subject matter. In extension, the fine line between fail and pass should serve to indicate the suitability of the person in being able to reliably use the knowledge and skill. The definition of fail/pass varies between fieldsfor example in certain Medicine courses, a pass is only given if the student can obtain a 70% grade. Obviously, one would only trust a doctor who could reliably perform a particular operation or diagnosis and perform suitable treatments for the patient. Yet, even if a particular course requires students to score a 50% only in the subject, it should still serve to delineate those that can versus those who cannot. Would you live in a house that is built by an engineer whose houses are sometimes designed and built reliably. Only 4 out of 10 houses collapsethats a 60% success rate, which is a pass right?

Perhaps what a pass in a subject means is that the student is able to reliably demonstrate knowledge and application of the core components of the subject. If a student passess electronics, he should be able to construct a basic closed circuit that switches a light on and off, every single time he is asked to. Perhaps he is not well versed with very complicated circuits, but at least there is a basic competency to the subject. How would an external party know how is the student assessed? Is there a common consensus between educational institutes? Does society and the public have to put every single person to the test again even if they have a formal acknowledgement of competency (e.g. a degree, diploma, certificate)? Just some food for thought.

This brings us to the topic of the adjustment of marks:

Teachers occasionally award bonus marks to students they feel should deserve extra academic credits. These extra effort demonstrated by students could take the form of participating in out-of-class activities that ideally should be related to the subject matter. Usually, this serves to reward students who are already proficient in the subject and are able to demonstrate their capabilities beyond what the course requirements measure.

The issue arises when students who tread between the pass and fail gap are awarded bonus marks which allows them to pass a subject, which they technically would be failing. Have they at least demonstrated the knowledge or skill of the core components of the subject? It is unlikely. Should such students deserve to fail or pass the subject? On the flip side, how about students whose marks are deducted because of a departmental policies that unfortunately penalizes students based on the fault of the student, but which is unrelated to the subject? Should they deserve to pass or fail? In certain countries or education systems, marks are adjusted against the mean/median, such that there will be a proportionate part of students that obtain the distribution of grades. For example, in the Malaysian high school graduate exams, the subject of Additional Mathematics is infamously known for having just a passing score of about 30 marks. If you obtain 60 marks, it is likely that you would have scored an A, or a distinction. Based on the discussion of the representation of marks above, would this be a fair adjustment? In this particular scenario, it is just a high school examination, so arguably it is not of a life/death importance. Certain courses and universities are also known to practice such adjustments. Should society be concerned?

The (possible) implications of condoning such lax representation of marks:

Assessments and marks are a core pillar of most education systems in the world, especially countries whose education is largely derived from the British. A vague and misrepresented assessment system might have various effects on society. Students could graduate into work without knowing their own capabilities, and thus create a mismatch of expectations between students and jaded employers. Bosses comment, A degree is not worth much anymore, since any Tom, Dick, or Harry can obtain one nowadays. In othe r cases, services and products might be of sub-par standardsmalpracticing doctors, collapsing structures. Of course, these are relatively far-fetched claims, and there are many factors such as societal expectations and the enforcement of minimum levels of service. However, without a particular reference standard in education, proliferate mediocrity (or worse, incompetency) can influence the general expectation, work ethics, and culture of a particular field. Who should be the one to fix this? Society? Employers? The government? Educational Institutes? Families? I believe it is a network of expectations and perspective. In dear Malaysia, many would attribute it to the government and its policies of implementing an adjusted nationwide high school examination, as well as the quota system which purpose is to graduate particular groups of student as a representation

of a successful education system (i.e. 70% of people have obtained a university degree; and not a focus on excellence or standard). I believe educational institutes and society too have a part to playwhy the focus on marks and it alone? Should marks and assessment not be an indication of the competency of the student? I write this article in hopes of getting people to think about the education system. Marks, assessments, grades and what they represent only covers a particular aspect of where education seems to be failing in providing society the productive people it needs, and individuals the learning and growth they need. Change can start from individualsI am just one teacher, but if I put thought into educating others, and inspire others to do so, we can slowly but surely make changes in education.

Some other food for thought:

In some disciplines, assessments cannot be even graded against a 100% cap. Marks represent what you need to achieve in the course, and does 100% represent full mastery of the subject? What about divergent, creative skills such as writing, performing, inventing? Can they be fairly graded against a 100% cap? There are other questions about educationis the focus on assessment and marks diverting our attention away from the most crucial aspect of education the process of learning

and thinking? A select few countries have already made the change to educating children in elementary and high school differently (see Education in Finland), and even without formal nation-wide assessments, the Finnish are considered one of the most highly ranked in international student assessments. Who and what does education ultimately serve? Should there be multiple channels of further education? I hope to cover these topics in the future. Stay tuned.

Вам также может понравиться

- 4 Steps To A Happy StartupДокумент32 страницы4 Steps To A Happy Startupksat909729Оценок пока нет

- Robert Frank - The Americans (1958)Документ84 страницыRobert Frank - The Americans (1958)nahuelmura555956495% (37)

- Coherent Extrapolated VisionДокумент38 страницCoherent Extrapolated VisiongraycrawfordОценок пока нет

- Irving Chernev - Logical Chess: Move by MoveДокумент256 страницIrving Chernev - Logical Chess: Move by Moveksat909729100% (11)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5783)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- TDS Tetrapur 100 (12-05-2014) enДокумент2 страницыTDS Tetrapur 100 (12-05-2014) enCosmin MușatОценок пока нет

- Introduction to Networks Visual GuideДокумент1 страницаIntroduction to Networks Visual GuideWorldОценок пока нет

- Master Your FinancesДокумент15 страницMaster Your FinancesBrendan GirdwoodОценок пока нет

- Edpb 506 Intergrated Unit Project RubricДокумент1 страницаEdpb 506 Intergrated Unit Project Rubricapi-487414247Оценок пока нет

- Tattva Sandoha PujaДокумент2 страницыTattva Sandoha PujaSathis KumarОценок пока нет

- AmulДокумент4 страницыAmulR BОценок пока нет

- Statement. Cash.: M.B.A. Semester-Ill Exadinatioh Working Capital Management Paper-Mba/3103/FДокумент2 страницыStatement. Cash.: M.B.A. Semester-Ill Exadinatioh Working Capital Management Paper-Mba/3103/FPavan BasundeОценок пока нет

- Maurice Strong by Henry LambДокумент9 страницMaurice Strong by Henry LambHal ShurtleffОценок пока нет

- Blood Culture & Sensitivity (2011734)Документ11 страницBlood Culture & Sensitivity (2011734)Najib AimanОценок пока нет

- Bhojpuri PDFДокумент15 страницBhojpuri PDFbestmadeeasy50% (2)

- TAFC R10 SP54 Release NotesДокумент10 страницTAFC R10 SP54 Release NotesBejace NyachhyonОценок пока нет

- Chapter 8 - Field Effect Transistors (FETs)Документ23 страницыChapter 8 - Field Effect Transistors (FETs)CHAITANYA KRISHNA CHAUHANОценок пока нет

- Cycling Coaching Guide. Cycling Rules & Etiquette Author Special OlympicsДокумент20 страницCycling Coaching Guide. Cycling Rules & Etiquette Author Special Olympicskrishna sundarОценок пока нет

- Eurythmy: OriginДокумент4 страницыEurythmy: OriginDananjaya PranandityaОценок пока нет

- Training of Local Government Personnel PHДокумент5 страницTraining of Local Government Personnel PHThea ConsОценок пока нет

- Supplier of PesticidesДокумент2 страницыSupplier of PesticidestusharОценок пока нет

- Corporate Office Design GuideДокумент23 страницыCorporate Office Design GuideAshfaque SalzОценок пока нет

- ACCOUNTING FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION FUNDSДокумент12 страницACCOUNTING FOR SPECIAL EDUCATION FUNDSIrdo KwanОценок пока нет

- BOM - Housing Template - 6.27.22Документ4 страницыBOM - Housing Template - 6.27.22Eric FuentesОценок пока нет

- Critical Growth StagesДокумент3 страницыCritical Growth StagesSunil DhankharОценок пока нет

- Block 2 MVA 026Документ48 страницBlock 2 MVA 026abhilash govind mishraОценок пока нет

- Scantype NNPC AdvertДокумент3 страницыScantype NNPC AdvertAdeshola FunmilayoОценок пока нет

- Business Data Communications and Networking 13Th Edition Fitzgerald Test Bank Full Chapter PDFДокумент40 страницBusiness Data Communications and Networking 13Th Edition Fitzgerald Test Bank Full Chapter PDFthrongweightypfr100% (12)

- FOREIGN DOLL CORP May 2023 TD StatementДокумент4 страницыFOREIGN DOLL CORP May 2023 TD Statementlesly malebrancheОценок пока нет

- ICE Learned Event DubaiДокумент32 страницыICE Learned Event DubaiengkjОценок пока нет

- Special Blood CollectionДокумент99 страницSpecial Blood CollectionVenomОценок пока нет

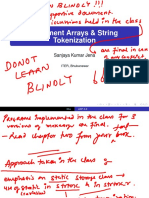

- USP 11 ArgumentArraysДокумент52 страницыUSP 11 ArgumentArraysKanha NayakОценок пока нет

- Torts and DamagesДокумент63 страницыTorts and DamagesStevensonYuОценок пока нет

- Latest Ku ReportДокумент29 страницLatest Ku Reportsujeet.jha.311Оценок пока нет

- Successfull Weight Loss: Beginner'S Guide ToДокумент12 страницSuccessfull Weight Loss: Beginner'S Guide ToDenise V. FongОценок пока нет