Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Cold War Blame

Загружено:

Francisco Fernando ArchiduqueИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cold War Blame

Загружено:

Francisco Fernando ArchiduqueАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Sam Walton

University of Sussex Undergraduate History Journal (No.01/2011)

Who was at fault for the Cold War?

Sam Walton

History and American Studies BA, University of Sussex (Brighton, UK)

Abstract: In this essay I seek to puncture the teleological view of Cold War history. In critiquing the current victorious version propagated by its chief proponent, John Lewis Gaddis, I hope to redeem a debate which Gaddis himself has declared is largely over. I utilise Gaddis own systematic approach but argue that this reflects more unfavourably on the US, and favourably on the USSR, than he would like to admit. I contend that a new, genuine post-revisionism is needed that can cope with nuance and allocates blame fairly to both sides. Keywords: Cold War; John Lewis Gaddis; post-revisionism; US; USSR; Cold War historiography

The happy, dialectal view of Cold War historiography tells the story of academics rejecting fallacious extremes and moving towards a more reasonable synthesis1. There are three main schools of thought on the explanation of the cold war 2. The first is exemplified by George Kennans Long Telegram3. The orthodox interpretation, favoured by the contemporary U.S administration, places the U.S on the moral high ground, simply reacting to Soviet aggression and expansionism. In the 1960s the revisionist school rose in response and instead blamed rampant American economic imperialism, which conflicted with reasonable Soviet security worries. Unimpressed by these simplistic, black and white interpretations a post revisionist school came to the fore. In this explanation both superpowers pushed their own agendas while misunderstanding and distrusting the others intentions. However, it seems to generally owe more to the traditionalist school; while regarding them both as blunderers the U.S was seen as the benevolent actor. In this essay I intend to evaluate the merits of the dominant brand of post-revisionism, which may be more accurately labelled the neoorthodox. I will pay particular attention to the eminent John Lewis Gaddis who seems quite dominant in this area of scholarship. In response to the ideology laced rhetoric of traditionalists some revisionists sought to excuse the Soviet Union as merely exhibiting the behaviour of a traditional great power. They were not forcing a dogma driven world revolution but simply practicing realpolitik. The post-revisionists have found it relatively easy to adjust their critique of soviet expansionism

1

John Lewis Gaddis, The Emerging Post-Revisionist Synthesis on the Origins of the Cold War, Diplomatic History, Volume 7, Issue 3 (July., 1983) 2 Timothy J. White, Cold War Historiography: New Evidence Behind Traditional Typographies, International Social Science Review, Volume 75, Numbers 3/4, (2000) 3 George Kennan, The Long Telegram, February 22, 1946, http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/coldwar/documents/episode-1/kennan.htm, Date Accessed: 24/11/10

Sam Walton

University of Sussex Undergraduate History Journal (No.01/2011)

as traditional grasping for power rather than an ideological war, although Gaddis argues for both4. However, they seek to bracket together Stalins diplomacy with his peculiar domestic operation and thus attribute the Cold War to Stalins paranoia and the very nature of authoritarianism. When Gaddis contends that Americans had begun to suspect... that the internal behaviour of states determined their external behaviour5 he is also indentifying the main thrust of his own argument. Indeed, Vojtech Mastny suggests that Stalins a ctions were a logical extension of the Soviet system which had bred him... that system was the true cause of the Cold War6. Moreover, they are subtly, perhaps insidiously, attempting to bring a moralistic tone back into the debate. Gaddis spends much of his first chapter characterising the two nations, contrasting autocratic tyranny with idealistic democracy. The U.S is then portrayed as carrying this idealism into international relations, a reluctant empire7, their only crime not being harsh enough with the Soviets8. This narrative runs through their interpretation of the evidence but it does not bear close scrutiny. Post revisionists disagree over whether Soviet expansionism was an extension of Stalins personality or his necessary response to powerful forces within his government9. It seems clear that while Stalins power did approach supremacy he was quite willing to use it to limit the expansionist tendencies of his more doctrinaire allies10, in this case in Greece. This seems to indicate Stalin was seeking to adhere to the famous percentages plan as agreed with Churchill, which paints a far more reasonable picture of the man. Much of Gaddis argument places far too much emphasis on Stalins paranoia and mistrust. He contends that Stalins espionage activities in relation to the Anglo-American bomb development project prove that he was a paranoid, unreliable ally11. The fact that two of three wartime allies failed to include the third in developing a revolutionary new weapon seems to escape his notice. Gaddis instead contends that the secrecy of the project was chiefly motivated by concerns over the Nazis12, Stalin being kept in the dark apparently an oversight. Gar Alperovitz draws on numerous U.S government documents to highlight just how central the Soviet Union was to American policy concerning the bomb 13. He reveals that major military authorities concluded that the bomb wasnt necessary to effect a Japanese surrender free of American casualties. These dissenters included Admiral Leahy 14, Supreme Commander Eisenhower15 and the U.S Strategic Bombing Survey16. Moreover, the bombing survey concluded that Japanese surrender may even have been brought about without a Soviet invasion. The bomb was not just designed to limit the expansion of Soviet interests in Asia but to alter the balance of power in Europe. Even Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War,

4 5 6

7 8 9

10 11 12 13 14 15 16

John Lewis Gaddis, We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, , 1997), pp.13-14 Ibid., p.35 Vojtech Mastny, Russias Road to the Cold War: Diplomacy, Warfare, and the Politics of Communism, 19411945, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979), p.306 Gaddis, We Now Know, pp.36-39 Mastny, Cold War, pp.309-310 Randall B Woods & Howard Jones, Dawning of the Cold War: The United States Quest for Order, (University of Georgia Press, 1991), pp.13-14 Ibid., pp.244-245 Gaddis, We Now Know, p.21; pp.92-96 Ibid., p.93 Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1995) Ibid., p.3 Ibid., p.4 Ibid., p.4

Sam Walton

University of Sussex Undergraduate History Journal (No.01/2011)

was concerned that the bomb was being used as stick to beat the Russians with 17. This not only challenges the idea that the collapse of the wartime alliance was the Soviets fault but seriously undermines the picture of America as an innocent, principled nation. Indeed, the evidence of the bomb highlights the usefulness of taking the PostRevisionist paradigm to its logical conclusion. The idea of foreign policy as an expression of the system, the domestic machine, can be fully extended to the U.S. The simplistic idea that the democratic sentiments of America restricted or stifled imperial tendencies18 seems to rest upon seeing the best in humanity, a naive stance. Woods and Jones suggest the end of mediation was triggered by the Republican partys decision... to challenge the democrats openly on foreign policy issues19. Truman then had to placate the increasingly powerful anti-soviet sentiment to maintain his political power. Daniel Yergin seems to contradict this interpretation of American policy by suggesting the American people were actually more isolationist than the political elite20. However, to gain the support for any coherent foreign policy diplomats like John Hickerson wanted a political speech to electrify the American people21. Sensationalist rhetoric resulted in a political and emotional response that quickly moved beyond the ability of more reasonable politicians to control. It seems that Stalins power was able to absorb irrational pressures on foreign policy far more than a political class who depended on the whims of the populace for their careers. In this post-revisionist narrative Stalins unwillingness to co-operate in the new world order marks him at fault for the Cold War. The two superpowers were ideologically incompatible but it was the communists uncompromising, ultimate aim of world revolution, their picture of all capitalists as exploitative enemies, that was the true problem. Gaddis argues that Wilsons vision of the post war world was one of multilateralism, of collective security22. It was Stalin who refused to embrace this principled vision, his unilateralism meant the U.S.S.R sought to maximise security for itself, while attempting to deny it to others23. It was Stalin again channelling the violent, authoritarian system of Soviet governance that made any rapprochement impossible24, the U.S was seeking to preserve its interests against aggressive Soviet expansionism. However, Melvyn Leffler suggests The American Conception of National Security was far more similar to the Soviet plan 2526 than historians like Gaddis and Bruce Kuniholm like to admit2728. When Leffler reasserts his argument that America planned for American hegemony over the At lantic and Pacific

17 18 19 20

21 22 23 24 25

26

27

28

Ibid., p.429 Gaddis, We Now Know, pp.13-16, 38-39 Woods and Jones, Dawning of the Cold War, p.98 Daniel Yergin, Shattered Peace: The Origins of the Cold War and the National Security State (London: Andre Deutsch, 1978) p.282 Ibid. Gaddis, We Now Know, pp.12-13 Ibid., p.13 Ibid., p.15 Melvyn P. Leffler, The American Conception of National Security and the Beginnings of the Cold War, 194548, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp. 346-381 Melvyn P. Leffler, Reply, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.391-400 John Lewis Gaddis, Comments, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.382-385 Bruce Kuniholm, Comments, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.385-390

Sam Walton

University of Sussex Undergraduate History Journal (No.01/2011)

oceans29 he suggests Gaddis has a limited understanding of the methods of control30. Gaddis explanation of the American empire certainly seems limited31. He portrays it as more of a broad alliance based on political self determination and economic integration than any relationship based on dominance. Indeed, he makes the remarkable contention that America made no systematic effort to suppress Socialism within its sphere of influence 32. In fact as early as 1947 the Americans were willing to extend their commitments in Europe to do exactly this by taking over British responsibilities in Greece33. The broad system of military bases and the numerous regime changes effected by the U.S34 certainly casts doubt on his idealised view of American foreign policy. Moreover, Leffler suggests the fact that American intervention in Greece, before the often cited Turkish and Iranian crises, is crucial35. It shows how America's expansion of its sphere of influence, its empire, was not a reaction to Soviet belligerence but a fear of sweeping radicalism across Europe. It responded to this independent socialist sentiment by using any means to crush the democratic far left. While the Soviet Union was certainly expansionist it was cautious, reactive and even Gaddis agrees that it certainly would have appeared to Stalin that America was remaking the world in its own image36. Misunderstanding and uncompromising visions of national security on both sides helped lead to the Cold War. However, America's view of any socialist activity as Soviet backed certainly helped ramp up the ideological polarisation of the conflict. Stalin was certainly ruthless, autocratic and brutal; a paranoiac and murderous perpetrator of genocide. He was expansionist in the grand tradition of European great powers. However, these traits do not necessarily mean that he, or the Soviet Union, were at fault for the development of the Cold War. The U.S was far less principled and far more aggressive than Gaddis and his colleagues would like to portray. This does not mean an exoneration of the Soviet Union, a return to the problems of the Revisionist school. It instead demands a far more nuanced and balanced approach to the evidence that apportions blame appropriately to both sides. The breakdown of wartime relations was not due to Stalins paranoia, he truly had reason to worry about the U.S led nuclear arms race. The very system of U.S government led to their foreign policy at the minimum matching the Soviets level of aggressiveness. Moreover, ideological inflexibility on both sides helped lead to misunderstandings and regrettable responses. All this leads to the conclusion that the Post-Revisionist Synthesis37, this growing consensus, is in urgent need of being reconsidered.

29 30

Leffler, The American Conception of National Security, p.349 Leffler, Reply, p.393 31 Gaddis, We Now Know, pp. 33-40; 43-46 32 John Lewis Gaddis, The Emerging Post-Revisionist Synthesis, p.174 33 Robert Frazier, Anglo-American Relations with Greece: The Coming of the Cold War, 1942-47 (Hong Kong: Macmillan, 1991) 34 Michael Grow, U.S. Presidents and Latin American Interventions: Pursuing Regime Change in the Cold War , (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008) 35 Leffler, Reply, pp.394-396 36 Gaddis, We Now Know, p.36 37 Gaddis, The Emerging Post-Revisionist Synthesis

Sam Walton

University of Sussex Undergraduate History Journal (No.01/2011)

Bibliography

Alperovitz, Gar; The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb (New York: Alfred A. Knopf Inc., 1995)

Frazier, Robert; Anglo-American Relations with Greece: The Coming of the Cold War, 194247 (Hong Kong: Macmillan, 1991) Gaddis, John Lewis; The Emerging Post-Revisionist Synthesis on the Origins of the Cold War, Diplomatic History, Volume 7, Issue 3 (July., 1983) Gaddis, John Lewis; Comments, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.382-385 Gaddis, John Lewis; We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997) Grow, Michael; U.S. Presidents and Latin American Interventions: Pursuing Regime Change in the Cold War, (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008) Kennan, George; The Long Telegram, February 22, http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/coldwar/documents/episode-1/kennan.htm, Accessed: 24/11/10 1946, Date

Kuniholm, Bruce; Comments, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.385-390 Leffler, Melvyn P; The American Conception of National Security and the Beginnings of the Cold War, 1945-48, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.346-381 Leffler, Melvyn P; Reply, The American Historical Review, Vol.89, No.2 (April., 1984, The University of Chicago Press), pp.391-400 Mastny, Vojtech; Russias Road to the Cold War: Diplomacy, Warfare, and the Politics of Communism, 1941-1945 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979) White, Timothy J; Cold War Historiography: New Evidence Behind Traditional Typographies, International Social Science Review, Volume 75, Numbers 3/4, (2000) Woods, Randall B. & Jones, Howard; Dawning of the Cold War: The United States Quest for Order, (University of Georgia Press, 1991) Yergin, Daniel; Shattered Peace: The Origins of the Cold War and the National Security State (London: Andre Deutsch, 1978)

Вам также может понравиться

- America and the Imperialism of Ignorance: US Foreign Policy Since 1945От EverandAmerica and the Imperialism of Ignorance: US Foreign Policy Since 1945Оценок пока нет

- 596 FinalpaperДокумент12 страниц596 Finalpaperapi-101494116Оценок пока нет

- Cold War Seven Summaries - ParadigmsДокумент7 страницCold War Seven Summaries - ParadigmsPeter LiОценок пока нет

- 1 Walter Lafeber, America, Russia and The Cold War, 1945-2000 (New York: Mcgraw-Hill, 2001), 1Документ6 страниц1 Walter Lafeber, America, Russia and The Cold War, 1945-2000 (New York: Mcgraw-Hill, 2001), 1Leigha JeanineОценок пока нет

- Debating The Origins of The Cold WarДокумент2 страницыDebating The Origins of The Cold WararmegateddyОценок пока нет

- GADDIS (1983) - Emerging Post-Rev SynthДокумент20 страницGADDIS (1983) - Emerging Post-Rev SynthTrepОценок пока нет

- Cold War HistoriographyДокумент14 страницCold War HistoriographyAlexa Lein0% (1)

- Thesis Statement of Cold WarДокумент6 страницThesis Statement of Cold Warwendyrobertsonphoenix100% (2)

- Russian HistoryДокумент8 страницRussian Historyrobbie.boydОценок пока нет

- Historiography On The Origins of The Cold WarДокумент4 страницыHistoriography On The Origins of The Cold Warapi-297872327100% (2)

- Cold War Thesis StatementsДокумент8 страницCold War Thesis Statementslauramillerscottsdale100% (2)

- The Old The New and The NewerДокумент8 страницThe Old The New and The Newervincentdesr2Оценок пока нет

- A-Level-Cold War DebatesДокумент8 страницA-Level-Cold War DebatesRukudzo ChadzamiraОценок пока нет

- Causes of The Cold War SummaryДокумент4 страницыCauses of The Cold War SummaryKhairul SincereОценок пока нет

- To What Extent Was The Cold War Inevitable?Документ3 страницыTo What Extent Was The Cold War Inevitable?mcwatkins3100% (1)

- Cox PipesДокумент38 страницCox PipesDiogo FerreiraОценок пока нет

- HamaДокумент5 страницHamaAli ZanganaОценок пока нет

- The Cold War - What Do We Now KnowДокумент25 страницThe Cold War - What Do We Now KnowHimaniОценок пока нет

- FulltextДокумент80 страницFulltextkrystellОценок пока нет

- KRAMER, M. (1999) - Ideology and The Cold War. Review of International Studies, 25 (4), 539-576Документ38 страницKRAMER, M. (1999) - Ideology and The Cold War. Review of International Studies, 25 (4), 539-576OAОценок пока нет

- Gaddis, The New Cold War HistoryДокумент3 страницыGaddis, The New Cold War HistoryCataОценок пока нет

- Cold War 8 Definitions FinalДокумент7 страницCold War 8 Definitions FinalLuis Alonso OcsaОценок пока нет

- Cold WarДокумент3 страницыCold WaryasacanОценок пока нет

- USA USSR RivalryДокумент6 страницUSA USSR RivalryZaina ImamОценок пока нет

- American History For Australasian Schools: Home Resources by Topic Resources by Theme Resources by TypeДокумент3 страницыAmerican History For Australasian Schools: Home Resources by Topic Resources by Theme Resources by TypeIsmail M HassaniОценок пока нет

- Cold War American ViewДокумент19 страницCold War American ViewjeiddiОценок пока нет

- Cold WarДокумент9 страницCold WarLuis R DavilaОценок пока нет

- Cold War Thesis StatementДокумент6 страницCold War Thesis Statementjacquelinethomascleveland100% (1)

- Cold War USA Vs USSR (1945 To 1991)Документ5 страницCold War USA Vs USSR (1945 To 1991)farhanОценок пока нет

- Truman To BlameДокумент2 страницыTruman To Blameobluda2173Оценок пока нет

- Westad-The Global Cold WarДокумент2 страницыWestad-The Global Cold WarAndrew S. TerrellОценок пока нет

- s5157412 HIR II Essay 1 Pleun SlootДокумент4 страницыs5157412 HIR II Essay 1 Pleun SlootPleun SlootОценок пока нет

- The Shadows of Cold War Over Latin America: The US Reaction To Fidel Castro's Nationalism, 1956 - 59Документ24 страницыThe Shadows of Cold War Over Latin America: The US Reaction To Fidel Castro's Nationalism, 1956 - 59matiasbenitez1992Оценок пока нет

- When Did The Cold War Begin FINAL VДокумент8 страницWhen Did The Cold War Begin FINAL VNick SharpeОценок пока нет

- History CourseworkДокумент5 страницHistory CourseworkrayhanaОценок пока нет

- At What Precise Point in Time Did The Cold War Between The USA and The USSR Become Unavoidable, and Why?Документ2 страницыAt What Precise Point in Time Did The Cold War Between The USA and The USSR Become Unavoidable, and Why?raaaaaawrОценок пока нет

- Deadly-Imbalances 9780231110730 31778Документ164 страницыDeadly-Imbalances 9780231110730 31778georgek1956100% (1)

- Term Paper On Cold WarДокумент7 страницTerm Paper On Cold Warafdtunqho100% (1)

- Bohri, Merchants of The Kremlin (Analisi Economica Dell'URSS in Ungheria)Документ61 страницаBohri, Merchants of The Kremlin (Analisi Economica Dell'URSS in Ungheria)Eugenio D'AlessioОценок пока нет

- Hollywood, The Blacklist, The Cold WarДокумент16 страницHollywood, The Blacklist, The Cold Warrueda-leon100% (1)

- Strategy As Art and CraftДокумент11 страницStrategy As Art and CraftantoniocaraffaОценок пока нет

- Latin America's Long Cold War by Greg Grandin, Specifically The Chapter Living inДокумент2 страницыLatin America's Long Cold War by Greg Grandin, Specifically The Chapter Living inDami AlukoОценок пока нет

- What Were The Cold War Fears of The American DBQ ThesisДокумент6 страницWhat Were The Cold War Fears of The American DBQ ThesisLeonard Goudy100% (2)

- Eisenhower and The First Forty Days Aft PDFДокумент39 страницEisenhower and The First Forty Days Aft PDFgladio67Оценок пока нет

- Origins Cold War HistoriographyДокумент18 страницOrigins Cold War HistoriographyAndrew S. Terrell100% (2)

- End of Cold War Historiography PaperДокумент21 страницаEnd of Cold War Historiography PaperAndrew S. Terrell100% (2)

- Cold WarДокумент34 страницыCold WarRIshu ChauhanОценок пока нет

- "Why Do They Hate Us So?" A Western Scholar's Reply: Puppet MastersДокумент6 страниц"Why Do They Hate Us So?" A Western Scholar's Reply: Puppet Mastersfrank_2943Оценок пока нет

- LECTURA No.22-NEOCON NATION-KAGANДокумент24 страницыLECTURA No.22-NEOCON NATION-KAGANRamiro Escobar La CruzОценок пока нет

- Who Was To Blame For The Cold War?Документ4 страницыWho Was To Blame For The Cold War?chalmers6Оценок пока нет

- Cold War Research Paper ThesisДокумент8 страницCold War Research Paper Thesischristinabergercolumbia100% (2)

- Research Paper Topics On Cold WarДокумент6 страницResearch Paper Topics On Cold Wargpxmlevkg100% (1)

- Khrushchev and The Berlin Crisis 1958-1962 (!!!)Документ33 страницыKhrushchev and The Berlin Crisis 1958-1962 (!!!)Ariane Faria100% (1)

- The Depiction of Stalin Between History and MythologyДокумент11 страницThe Depiction of Stalin Between History and MythologyMrWaratahs100% (1)

- Module 2 - Topic 2. Cold War vs. GlobalizationДокумент7 страницModule 2 - Topic 2. Cold War vs. GlobalizationRosalyn BacolongОценок пока нет

- Can The United States and China Avoid A Thucydides Trap?: Published An EssayДокумент3 страницыCan The United States and China Avoid A Thucydides Trap?: Published An EssayVitorHugoMartinsОценок пока нет

- The Long War: A New History of U.S. National Security Policy Since World War IIОт EverandThe Long War: A New History of U.S. National Security Policy Since World War IIОценок пока нет

- The First Domino - Int'l Decision Making During Hungary 1956.johanna GranvilleДокумент448 страницThe First Domino - Int'l Decision Making During Hungary 1956.johanna Granvillekfyt22282% (11)

- Phases of Cold WarДокумент18 страницPhases of Cold WarBrijbhan Singh RajawatОценок пока нет

- GladioДокумент4 страницыGladioFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Essay-Review Post Yugoslav SpaceДокумент10 страницEssay-Review Post Yugoslav SpaceFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Yugoslavia Artículos y Libros 2Документ3 страницыYugoslavia Artículos y Libros 2Francisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Reflections Cold War Historiography CrapolДокумент13 страницReflections Cold War Historiography CrapolFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Jugoslavia and CroaciaДокумент18 страницJugoslavia and CroaciaFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Yugonostalgia 4Документ28 страницYugonostalgia 4Francisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- GladioДокумент3 страницыGladioFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Why The End of The Cold War Doesn't Matter: The US War of Terror in ColombiaДокумент17 страницWhy The End of The Cold War Doesn't Matter: The US War of Terror in ColombiaFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- NIOD PrologueДокумент110 страницNIOD PrologueFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Prosecutor Vs MarticДокумент200 страницProsecutor Vs MarticFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Yugonostalgia 3Документ12 страницYugonostalgia 3Francisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Appendix Media ReportingДокумент73 страницыAppendix Media ReportingFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Srebrenicareportniod en Part03Документ582 страницыSrebrenicareportniod en Part03Francisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Appendix The Role of HistoryДокумент139 страницAppendix The Role of HistoryFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- The Politicar Economy Background of Yugoslavia DissolutionДокумент17 страницThe Politicar Economy Background of Yugoslavia DissolutionFrancisco Fernando ArchiduqueОценок пока нет

- Teach Yourself SloveneДокумент92 страницыTeach Yourself SloveneMilica Kocić86% (7)

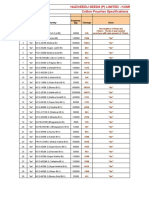

- Sona Koyo Steering Systems Limited (SKSSL) Vendor ManagementДокумент21 страницаSona Koyo Steering Systems Limited (SKSSL) Vendor ManagementSiddharth UpadhyayОценок пока нет

- God's Word in Holy Citadel New Jerusalem" Monastery, Glodeni - Romania, Redactor Note. Translated by I.AДокумент6 страницGod's Word in Holy Citadel New Jerusalem" Monastery, Glodeni - Romania, Redactor Note. Translated by I.Abillydean_enОценок пока нет

- Emergency Rescue DrillДокумент13 страницEmergency Rescue DrillbalasubramaniamОценок пока нет

- Acitve and Passive VoiceДокумент3 страницыAcitve and Passive VoiceRave LegoОценок пока нет

- Surge Protectionfor ACMachineryДокумент8 страницSurge Protectionfor ACMachineryvyroreiОценок пока нет

- Vocabulary Words - 20.11Документ2 страницыVocabulary Words - 20.11ravindra kumar AhirwarОценок пока нет

- Comparing ODS RTF in Batch Using VBA and SASДокумент8 страницComparing ODS RTF in Batch Using VBA and SASseafish1976Оценок пока нет

- IAB Digital Ad Operations Certification Study Guide August 2017Документ48 страницIAB Digital Ad Operations Certification Study Guide August 2017vinayakrishnaОценок пока нет

- EMP Step 2 6 Week CalendarДокумент3 страницыEMP Step 2 6 Week CalendarN VОценок пока нет

- ReproTech, LLC Welcomes New President & CEO, William BraunДокумент3 страницыReproTech, LLC Welcomes New President & CEO, William BraunPR.comОценок пока нет

- New Count The DotsДокумент1 страницаNew Count The Dotslin ee100% (1)

- Anglicisms in TranslationДокумент63 страницыAnglicisms in TranslationZhuka GumbaridzeОценок пока нет

- Bon JourДокумент15 страницBon JourNikolinaJamicic0% (1)

- Dry Wall, Ceiling, and Painting WorksДокумент29 страницDry Wall, Ceiling, and Painting WorksFrance Ivan Ais100% (1)

- D. Michael Quinn-Same-Sex Dynamics Among Nineteenth-Century Americans - A MORMON EXAMPLE-University of Illinois Press (2001)Документ500 страницD. Michael Quinn-Same-Sex Dynamics Among Nineteenth-Century Americans - A MORMON EXAMPLE-University of Illinois Press (2001)xavirreta100% (3)

- Novi Hervianti Putri - A1E015047Документ2 страницыNovi Hervianti Putri - A1E015047Novi Hervianti PutriОценок пока нет

- God Whose Will Is Health and Wholeness HymnДокумент1 страницаGod Whose Will Is Health and Wholeness HymnJonathanОценок пока нет

- Project CharterДокумент10 страницProject CharterAdnan AhmedОценок пока нет

- Civil and Environmental EngineeringДокумент510 страницCivil and Environmental EngineeringAhmed KaleemuddinОценок пока нет

- List of Notified Bodies Under Directive - 93-42 EEC Medical DevicesДокумент332 страницыList of Notified Bodies Under Directive - 93-42 EEC Medical DevicesJamal MohamedОценок пока нет

- Didhard Muduni Mparo and 8 Others Vs The GRN of Namibia and 6 OthersДокумент20 страницDidhard Muduni Mparo and 8 Others Vs The GRN of Namibia and 6 OthersAndré Le RouxОценок пока нет

- Self Authoring SuiteДокумент10 страницSelf Authoring SuiteTanish Arora100% (3)

- DLL Week 7 MathДокумент7 страницDLL Week 7 MathMitchz TrinosОценок пока нет

- A Mercy Guided StudyДокумент23 страницыA Mercy Guided StudyAnas HudsonОценок пока нет

- AX Series Advanced Traffic Manager: Installation Guide For The AX 1030 / AX 3030Документ18 страницAX Series Advanced Traffic Manager: Installation Guide For The AX 1030 / AX 3030stephen virmwareОценок пока нет

- Law - Midterm ExamДокумент2 страницыLaw - Midterm ExamJulian Mernando vlogsОценок пока нет

- National Healthy Lifestyle ProgramДокумент6 страницNational Healthy Lifestyle Programmale nurseОценок пока нет

- Agitha Diva Winampi - Childhood MemoriesДокумент2 страницыAgitha Diva Winampi - Childhood MemoriesAgitha Diva WinampiОценок пока нет

- Company Profile RadioДокумент8 страницCompany Profile RadioselviОценок пока нет

- Cotton Pouches SpecificationsДокумент2 страницыCotton Pouches SpecificationspunnareddytОценок пока нет