Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Wittgenstein and Heidegger - Orientations To The Ordinary Stephen Mulhall

Загружено:

rustycarmelina108Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Wittgenstein and Heidegger - Orientations To The Ordinary Stephen Mulhall

Загружено:

rustycarmelina108Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

Stephen Mulhall

In any attempt to open and maintain lines of communication between the estranged traditions of Anglo-American analytical philosophy and those at present predominant in France and Germany, the texts of Wittgenstein and Heidegger offer an invaluable resource. From the Continental point of view, Wittgensteins work is at once intimately acquainted with, and radically critical of, the technicalities, doctrinal assumptions and methodological parameters of the analytical tradition; and his critical perspective is not only well-earned but based upon a vision of the human relation to language, thought and the world which has stimulated much discussion of its possible intersections with themes in the work of Derrida, Habermas and Heidegger. From the point of view of those in the analytical tradition who are prepared to take Wittgensteins methodological critique of it seriously, then it is with the central themes of Heideggers work (rather than that of Derrida or Habermas) that Wittgensteins vision seems most intimately, even if obscurely, aligned - in their mutual emphasis upon the centrality of practical activity to human existence and the treacherous transparencies of ordinary language and life, and in the atmosphere of spiritual fervour which pervades their philosophizing. It is, however, far easier to sense such subterranean affinities than to bring them to the light - far easier to specify these philosophers general family resemblances than to compare the finer details of their respective physiognomies; and the difficulty is compounded by the fact that any more systematic comparisons must respect the fundamental differences of tone, temperament and trajectory that each inherits (however uneasily) from their respective traditions. Nonetheless, in this paper I want to initiate such a project of physiognomic comparison, or more precisely to elucidate, elaborate and extend a comparative enterprise some of whose elements have guided much that is most fruitful in the writings of Stanley Cavell. And as a way of demonstrating the extensively and mysteriously ramifying nature of the affinities that are active in these texts, I have organized my discussion around three very different dimensions of comparison: that of specific imagery or metaphors - which turn out to be much more than merely rhetorical or illustrative (their talk of tools), that of general theme or guiding concept (their relation to the ordinary), and that of their conception of the nature of their authorship (their moral perfectionism).

European /ouml of Philosophy 2 2 lSSN 0966-8373 pp. 143-164. @ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994. 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 IF, UK, and 238 Main Street, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA.

144

Stephen M ul ha12

1. Tools and Equipment: Seeing Aspects

The overall conception of word meaning that Wittgenstein opposes to the Augustinian emphasis on words as names is well known: For a large class of cases - though not for all - in which we employ the word meaning it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language (Wittgenstein (1958), Q 43); Look at the sentence as an instrument, and at its sense as its employment (PI, Q 421); Think of the tools in a tool-box: there is a hammer, pliers, a saw, a screw-driver, a rule, a glue-pot, glue, nails and screws. - The functions of words are as diverse as the functions of these objects (PI, Q 11). Much attention has been lavished on the meaning as use aspect of this conception, but little upon the invocation of instruments, tools and equipment in Wittgensteins imagery - an invocation which seems particularly resonant in the company of Heidegger, whose later emphases upon thinking as a handicraft are presaged in the centrality to Being and Time of the distinction between presence-at-hand and readiness-to-hand, and its articulation in terms of examples drawn from the world of tools and equipment. When Wittgenstein invokes the analogy of tools, however, its implications are usually taken to be strictly limited, and thus doubly disanalogous to those set to work by Heideggers use of the same imagery. When, for example, Wittgenstein tells us that words are like the handles in the cabin of a locomotive, all looking more or less alike since they are all supposed to be handled (PI Q 12), this image of words as one amongst the many types of tool that the human hand handles is understood to imply only that their life too is manifest in the use humans make of them. When, however, Heidegger talks of the equipmentality of words - for example, in Being and Time, when he states that Language is a totality of words - a totality in which discourse has a worldly Being of its own; and as an entity within-the-world, this totality thus becomes something which we may come across as ready-to-hand (BT, p. 204) - he means to invoke not just the concept of use but the full weight of his earlier analysis of readiness-to-hand. And where Wittgenstein seems to show no interest in invoking the example of tools to explicate the human relation to entities other than words, Heideggers talk of words as ready-to-hand draws linguistic symbols into the orbit of his characterization of the primordial relation in which Dasein stands to all entities. This appearance of a double disanalogy is, however, deceptive; and the illusion can be dissipated by noting the centrality of the concept of seeing as to the work of both philosophers. In Heideggers case, the importance of this concept is evident. His analysis of readiness-to-hand is intended to demonstrate that the equipmentality of any given piece of equipment is constituted by the multiplicity of reference- or assignment-relations which define its place in a totality of equipment, an assignment which becomes explicit only when it is disturbed - if a tool is damaged or missing, or an entity is encountered as an obstacle to the work. What is thereby revealed is the constitutive role of understanding for Being-in-the-world: seeing for the first time what the

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

145

damaged entity was ready-to-hand with and ready-to-hand for amounts to seeing its place in a totality of involvements that is ultimately grounded in a forthe-sake-of-which that pertains to the Being of Dasein, and to seeing that this totality is that in which Dasein is ordinarily arcumspectively absorbed. But the structure of this implicit comprehension of entities ready-to-hand in the world is the structure of something as something: for an entity to be ready-to-hand is for it to be ready-to-hand for such-and-such a purpose - the hammer for making something fast,, the table for writing, the bridge for crossing the river; so our encountering an entity as ready-to-hand amounts to our encountering it as a hammer, a table or a bridge rather than perceiving it as a bare object that we interpret in certain ways. Heidegger then goes on to trace this somethingas something structure to the realm of meaning and language. Meaning refers to the field wherein the intelligibility of anything (as the particular thing it is) maintains itself, the uponwhich of Daseins understanding projection; and this formal-existential framework is bequeathed to us through the existential-ontological foundation of language that Heidegger labels discourse. Discourse, understood as the Articulation of intelligibility, is what permits the disclosedness of entities withinthe-world and thus founds the comprehending perception of entities as readyto-hand; it is the necessary structure of the field of meaning and so of comprehending something as something. And although it therefore accounts for the intelligibility of all objects and so has application far beyond the realm of linguistic symbols understood as a totality of ready-to-hand entities, Heidegger is careful to stress that (as the label he gives to these structures suggests) language is the way in which Discourse is expressed. When we turn from Being and Time to the second Part of the Philosophical Investigations, it is difficult to avoid being struck by the existence of an analogous pattern of analysis in Wittgensteins remarks on seeing aspect^.^ He focuses on the seemingly paradoxical experience of the dawning of one aspect of a dualaspect drawing - our sense that the figure has changed even though we know that nothing in its configuration has altered - and argues that no model of perception based upon the interpretation of a bare visual impression can accommodate it; but he also attempts to dissolve that air of paradox in his own way. According to him, our inclination to express our sudden perception that a picture-duck is also a picture-rabbit in terms that are ordinarily employed to register a change in a perceived objects properties (Now its a rabbit!) is simply a striking manifestation of the fact that our everyday relation to pictures is of a particular sort - one he encapsulates in his claim that we generally regard pictures as we do the objects they depict (PI, p. 205e). When we perceive a given (representative) painting or drawing, we react immediately to the features and propekes of the depicted landscape or face; a description of it in terms of what it depicts is not only known to be applicable but unhesitatingly applied, ready-tohand; if we catch only a glimpse of it, we might make errors in describing or transcribing it, but they would be errors about the depicted world (e.g. mistakenly identifymg an arrow as a spear) rather than about the properties of

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

146

Stephen Mulhall

the pictorial medium (e.g. misidentifymg the length or orientation of a pencilstroke); we place paintings of valued people and places on our walls. In general, our attitude to pictures is such that we do not simply recognize that they depict and what they depict, but take their specific pictorial identity - their identity as a picture of x rather than y - for granted in our dealings with them. Against this background, the paradox of aspect-dawning seems completely unsurprising. For if the tie-up between pictures and what they depict informs our relationship with them in such a way, then we will tend to regard the picture of a duck as being as different from the picture of a rabbit as a duck is from a rabbit; and we will accordingly be tempted to give expression to the sudden realization that the same figure is both a picture-duck and a picture-rabbit in terms which suggest that the original figure has been transformed into a completely different one. Another way of putting this dissolution of the paradox is to say that our characteristic reaction to the dawning of an aspect is simply one striking manifestation of our more general attitude to objects of the type under examination: the experience of aspect-dawning disrupts the everyday relation to pictures which makes that experience possible, and thereby brings that inconspicuous phenomenon into the foreground of our lives. And what is thereby highlighted is the fact that we regard such pictures as - we take them for granted as - the particular kind of objects that they are rather than confronting them as bare objects in need of an interpretation. Heideggers category of readiness-to-hand seems a very handy way of encapsulating the nature of this everyday relation, which Wittgenstein refers to as regarding as, seeing as opposed to knowing or continuous seeing-as. It brings out the fact that part of what is meant by regarding as is made manifest in the smooth and seamless ways in which objects are woven into our verbal and non-verbal practical activity, the unhesitating way in which they are taken up as means for achieving our goals and purposes; and it also underlines the relation between aspectdawning and continuous seeing of an aspect - the former amounting to a disturbance, and so a making explicit, of the assignment-structure (the structure of something as something) whose everyday implicitness is what the latter picks out. And if it is legitimate to talk, however provisionally, of the readiness-tohand (the handiness) of pictures, then it is important to note that Wittgenstein sees the structural pattern just identified as active in regions other than the pictorial. To begin with, he explicitly connects his analysis with the realm of language, the totality of words (PI, p. 214d). Here, the analogue to the dawning of a pictorial aspect is experiencing the meaning of a word, e.g. finding intelligible a request to read or pronounce the word bank and mean it as a river bank, or feeling that a word lost its meaning and became a mere sound after reading or pronouncing it ten times; and once again, what is invoked to defuse the strangeness of such phenomena is the nature of our general relation to words. For of course, a word could not be felt to lose its meaning and become a mere mark if it were typically encountered as a bare mark upon which a linguistic interpretation must then be projected: the material aspect of a word can dawn on

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

147

us precisely because we continuously perceive the written and spoken elements of language as meaningful words and sentences. And talk of reading or pronouncing a word in isolation in each of its different meanings presupposes two things: first, an awareness of those meanings and of their differences - an acquaintance with a words location (as the bearer of one or more specific technique of use) in relation to other words in the field of that language; and second, an ability to find it intelligible that words deployed in isolation - outside the usual contexts of their application - might bear traces of those techniques. In such cases, it is as if we think that words bear their meaning on their face - as if their specific tie-ups of comparison and contrast with other words, their specific location in the linguistic field, that which makes them the specific words they are, do not just lie in the background but have been absorbed into the appearance and sound of the word, as if words each possessed a unique physiognomy, functioning as likenesses or portraits of their meaning (PI, p. 218g). In this respect, experiencing the meaning of a word is simply a striking manifestation of the degree to which human beings are at home with words: our inclination to regard the words themselves as having assimilated these tie-ups is a reflection of the degree to which we have assimilated those words -the degree to which they are not merely entities with a function or use in our lives but ready-to-hand for us as meaningful. Although Wittgenstein does not explicitly extend these analyses far beyond the realms of pictures and words, he does imply that the role of psychological concepts and so of other persons in our lives might be open to construal in terms of aspect perception; and more generally the structure or pattern that he identifies seems to be a perfectly generalizable one. The crucial point is that the notion of continuous seeing-as captures a particular familiarity or at-homeness that human beings can manifest in relation to entities understood as particular kinds of object. Since (representative)pictures just are entities that are correctly described by describing what they depict, and words just are bearers of specific meanings, continuously regarding such pictures as we do what they depict, and continuously perceiving words as bearers of specific meanings, amounts to taking for granted their specific identities as that is determined by the field of concepts which have application to them. In other words, these phrases describe a scenario in which the concepts that determine those objects as objects of a particular kind inform our relation to those objects rather than standing as a mediating layer between us and them; continuous aspect perception specifies one inflection or mode of our concept-laden relation to pictures and words. But since the human form of life is one in which our relations to any and all of the entities we encounter are shot through with the conceptual/linguistic structures . that have application to those entities, then continuous seeing-as must be one possible mode of our relation to any and all of the entities we encounter in the world. In short, if pictures and words can be and typically are ready-to-hand for us, then the same must be true of all the entities in all the regions of our world. On this reading, then, Wittgensteins explorations of aspect perception generate a vision of the distinctive human form of life with objects that

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

148

Stephen Mulhall

resembles rather than contrasts with Heideggers in the two respects we isolated earlier: the comparison of words with tools invokes not just the concept of use but that of readiness-to-hand, and that latter concept is understood to range far beyond the realm of words. Moreover, its generalizability depends upon the invocation of determinants of intelligibility-structures (conceptual structures) that Wittgenstein regards as essentially linguistic - possessed of a range of application far beyond the realm of linguistic symbols, but ultimately given expression in language; where Heidegger talks of Rede, Wittgenstein prefers the term Grammar. In all these respects, this feature of Wittgensteins later philosophy bears a clear family resemblance to that of the early Heidegger grounds enough, perhaps, to explore further the question of whether they are members of related philosophical species.

2. Phenomenology and Language: Orientations to the Ordinary

The concept of the ordinary is interpreted by the Heidegger of Being and Time as the concept of the everyday; and in this guise it is at work in his text at many levels, three of which I want to mention here. The first level is that of philosophical methodology. Heideggers inflection of the phenomenological method which he inherited from Husserl involves the idea that the goal of philosophical inquiry is the uncovering of the underlying structures of phenomena as an essential part of grasping them in their Being as phenomena, and so of uncovering Being as such. Here, phenomenology means: to let that which shows itself be seen from itself in the very way in which it shows itself from itself. As Heidegger puts it: Because phenomena, understood phenomenologically, are never anything but what goes to make up Being, while Being is in every case the Being of some entity, we must first bring forward the entities themselves if it is our aim that Being should be laid bare; and we must do this in the right way. These entities must likewise show themselves with the kind of access which genuinely belongs to them. And in this way, the ordinary concept of phenomenon becomes phenomenologically relevant. (BT, p. 63) Even though the phenomenologist must push beyond the ordinary understandings of the phenomena of ordinary life if she is to reveal the fundamental structures which make it possible for entities to reveal themselves to us, the poiot of departure for these investigations of Being must be the everyday appearance of entities and the everyday modes of access we have to them -with their phenomenology. In short, to say that we must begin with how entities appear to us proximally and for the most part is just to say that we must begin with the everyday ways in which they show themselves to Dasein. The second level at which the concept of the everyday plays a role is generated

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

149

by Heideggers decision to regard a phenomenological analysis of the Being of Dasein (his term for the distinctively human mode of existence) as an essential first step in any analysis of Being; for, given the points just made about the phenomenological method, it follows that any such analysis of Dasein must begin from how it is proximally and for the most part - from its everydayness:

. . . [W]e have no right to resort to dogmatic constructions and to apply just any idea of Being and actuality to this entity, no matter how selfevident that idea may be; nor may any of the categorieswhich such an idea prescribes be forced upon Dasein without proper ontological consideration. We must rather choose such a way of access and such a kind of interpretation that this entity can show itself in itself and from itself. And this means that it is to be shown as it is proximally and for the most part - in its average everydayness ... Thus by having regard for the basic state of Daseins everydayness we shall bring out the Being of this entity in a preparatory fashion. (BT, pp. 37-8).

At this stage, then, the focus upon an entity in its everydayness is intended as a way of avoiding the imposition of traditional or time-hallowed philosophical categories which effectively prejudge the question of the Being of any given entity. In this sense, Heideggers concept of the everyday is opposed to that of the philosophical; it is that which philosophy represses but that without which philosophy cannot begin to move towards its goal of understanding Being. The third level at which the concept of the everyday is at work is that of the specific results or insights which emerge from Heideggers preparatory elucidation of Daseins everydayness. Here, what we find first is that the everyday has contributed to its own philosophical repression. Although Heidegger concludes that the Being of Dasein is Being-in-the-world, i.e. that Dasein always already dwells alongside what is ready-to-hand within-the-world rather than confronting objects as present-at-hand, this very handiness of objects ensures its own obscurity by ensuring its own inconspicuousness. If the primordial relation to objects is as pieces of equipment, as tools employed in the task of accomplishing Daseins projects, then Daseins focus will typically be upon the goals for which it is working and for which the objects are ready-tohand; Dasein will thus sight through the objects rather than focusing upon the objects themselves. Only when the assignment of these objects towards a specific goal is disturbed or disrupted, e.g. if a tool is damaged or missing, does the equipmental structure - and so the equipment itself - become evident: When an assignment to some particular towards-this has been thus circumspectively aroused, we catch sight of the towards-thisitself, and along with it everything connected with the work - the whole workshop - as that wherein concern always dwells. The context of equipment is lit up, not as something never seen before, but as a totality constantly sighted beforehand in circumspection. (BT, p. 105).

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

150

Stephen Mulhull

Ironically, however, this moment of lighting up (of aspect-dawning) is also and necessarily one in which the readiness-to-hand of the objects has been transformed into presentness-at-hand - we confront them as objects which no longer fit into our tasks but rather stand as alien or other to us, as things to be theoretically cognized. In this sense, Daseins everyday relation to objects is necessarily self-concealing,and can reveal itself to us only through its loss; when we are immersed in it we are unaware of it, and when we become aware of it we are no longer immersed in it. It is as if the everyday is something we can grasp only under the aspect of loss. The second lesson we learn from Heideggers elucidation of Daseins everydayness is its inauthenticity. The everydayness in which Dasein exists proximally and for the most part is average everydayness: it is a form of Beingwith-Others in which ones own Being is dissolved into the kind of Being of the others, the they. We take pleasure and enjoy ourselves as they they pleasure; we read, see and judge about literature and art as they see and judge; likewise we shrink back from the great mass as they shrink back; we find shocking what they find shocking. The they, which is nothing definite, and which all are, though not as the sum, prescribes the kind of being of everydayness. (BT, p. 164) This subjection to the common or average levels down the possibilities-for-Being which are of the essence of Dasein; Dasein, the kind of Being whose potentialityfor-Being is an issue for it, submerges itself into an anonymity which extinguishes its individuality and leads to its absorption in idle talk, curiosity, ambiguity and fallenness - modes of its existence which constantly tear the understanding away from the projecting of authentic possibilities and into the tranquillized supposition that everything is within its reach or that everything is possible. This groundless floating, this uprooted being-everywhere-and-nowhere, is Daseins average everydayness; it is the ordinary understood as the average. What Heidegger opposes to this average everydayness is his conception of authentic Being-in-the-world:Dasein achievesthis mode by resolutely anticipating its death as its ownmost non-relational possibility, as something which lays claim to it as an individual Dasein, thus tearing itself away from the they: Dasein is authentically itself only to the extent that, as concernful Beingalongside and solicitous Being-with, it projects itself upon its ownmost potentiality-for-Being rather than upon the possibility of the they-self. (BT, p. 308) Setting aside for the moment the question of the nature of resoluteness, it is worth noting first of all that, although Heidegger outlines this authentic mode of Being-in-the-world by contrast with an inauthentic mode of that Being,

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinay

151

specifically with its average everydayness, he does not regard it as something to be defined in opposition to the everyday per se. Authentic Being-in-the-world is not a transcendence of or escape from everydaynessbut a mode of everydayness; it is not an extraordinary mode of Being, but a mode of inhabiting the ordinary: . . , authentic existence is not something which floats above falling everydayness; existentially, it is only a modified way in which such everydayness is seized upon. (BT, p. 224) But what is the nature of this authentic mode of grasping everydayness? Heidegger labels this mode resoluteness, and characterizes it as follows: In resoluteness, the issue for Dasein is its ownmost potentiality-forBeing, which, as something thrown, can project itself only upon definite factical possibilities. Resolution does not withdraw itself from actuality, but discovers first what is factically possible; and it does so by seizing upon it in whatever way is possible for it as its ownmost potentiality-forBeing in the they. (BT, p. 346) Resoluteness is thus not just the taking of a decision to adopt one particular project rather than another; it involves distinguishing those available projects which are closest to Dasein solely because of its lostness in the they from those which are closest to Dasein in the sense of being Daseins ownmost possibilities. This means that resoluteness is as much the disclosure and determination of what is factically possible as it is a response to it; it involves fixing which possibilities are possibilities for a given human being understood in terms of thrown projection - as a specific individual, determined by her past and open to the future, whose potentiality-for-Being is an issue for her. It means grasping each present moment in terms of the past and the future rather than as an isolated (groundless, floating) atom. This emphasis on thrown projection makes it unsurprising that Heideggers final and most fundamental interpretation of Daseins Being is in terms of temporality. This interpretation is, of course, desperately obscure; but it entails that his final and most fundamental interpretation of authentic everydayness must also be in terms of temporality. Some hints as to the form this interpretation might have taken are to be found when Heidegger sketches in his account of the temporal meaning of everydayness: Everydayness manifestly stands for that way of existing in which Dasein maintains itself every day. And yet this everyday does not signify the sum of those days which have been allotted to Dasein in its lifetime . . . Everydayness means the how in accordance with which Dasein lives unto the day . . . To this how there belongs further the comfortableness of the accustomed, even if it forces one to do something burdensome and repugnant. That which will come tomorrow (and this is what everyday concern keeps awaiting) is eternally yesterdays. In everydayness, everything is all one and the same, but whatever the day

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

152

Stephen Mulhall

may bring is diversification . . . In living unto its days Dasein stretches itself along temporally in the sequence of those days. The its all one and the same, the accustomed, the like yesterday, so today and tomorrow, and for the most part, these are not to be grasped without recourse to this temporal stretching-along of Dasein . . . And is it not also a Fact of existing Dasein that in spending its time it takes time into its reckoning astronomically and calendrically? Everydayness is determinative for Dasein even when it has not chosen the they for its hero . . . (BT, pp. 422-3)

Despite the obscurities, it seems that Heidegger is offering us a reinterpretation of the everyday as the daily, the day-to-day, the diurnal. Everydayness is seen as stretching along the sequence of ones days in a way which contains diversity within identity; it is a mode of repetition. As such, however, it can be grasped in different ways: it can be mediated through the understanding of the they, in which case Dasein lives unto the day by levelling out the distinctness of each new, present moment, interpreting it according to custom as identical with those past moments which make up its everyday life; or Dasein can dispense with the they as its hero, and remain open to every new day as structured in a way that it shares with every other day but as also possessing a potential for diversification from the accustomed past. Authentic everydayness thus seems to signify a mode of diurnal repetition through which identity and diversity might be held in the fruitful tension which is most appropriate to a Being which is essentially thrown projection. And once again the key to authenticity lies not in the repudiation or transcendence of the ordinary but in a way of re-appropriating it; for Heidegger, average everydayness, re-interpreted as one mode of diurnal repetition, is opposed to authentic everydayness re-interpreted as an alternative mode of diurnal repetition. At no point in his early philosophy does Heideggers analysis entirely lose touch with the ordinary; it orients him from first to last. The concept of the ordinary functions in Wittgensteins text to delimit what seems to be a species of language; but when Wittgenstein is categorized together with Austin as an ordinary language philosopher, ones response is likely to be a mixture of agreement, dissent and bafflement. Agreement, because the phrase and the concept of ordinary language clearly plays some role in Wittgensteins work; dissent, because of the ways in which such a label elides crucial differences between Wittgensteins and Austins orientations; but primarily bafflement, because it typically remains unclear just exactly what the concept of ordinary language is supposed to signify. Ordinary language as opposed to what? Not as opposed to extraordinary language. Wittgenstein is perfectly happy for his interlocutors to alter the meanings of their words, or to invent new language games which might have more utility given certain conceivable changes in the circumstances under which the game is to be played; and in those extraordinary contexts philosophical confusions could easily arise and their dissolution would

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

153

require reference to the altered grammar of the words being employed. Nor is ordinary language a synonym for common sense, as if Wittgenstein is interested in defending the beliefs of the Stone Age against those of this so-called twentieth century. Wittgensteins concern with ordinary language is not with the beliefs expressed in that language but with the rules which fix the meanings of the terms of that language and so permit the possibility of expressing anything whatever in it. His concern is with grammar, not with the truth or falsity of statements employing that grammar; what philosophy must plot are the bounds of sense, not the lineaments of truth. In fact, for Wittgenstein ordinary language seems rather to stand in contrast with formal language; ordinary language is a synonym for natural language. The claim is that the exploration and dissolution of philosophical confusions does not require the construction or deployment of a symbol-system or concept-script whose terms are geometrically defined and whose structure conforms transparently to that of first-order predicate calculus; and such symbol-systems should not be seen as the underlying structure of natural languages either. They are human inventions, designed to perform certain tasks with efficiency and to make certain conceptual relations less complex or more perspicuous; but the idea that ordinary language is in some way deficient in comparison to such formal languages, or in need of supplementation or substitution by them, is one of the key philosophical confusions that Wittgenstein is concerned to dissipate. His emphasis upon the ordinary is thus in the first instance an emphasis upon natural languages being in order as they stand - upon language as natural and ordered, as naturally ordered; and in the second instance it is an emphasis upon the fact that ordinary language is not a construction or invention of specific human beings for specific purposes but something which an individual is capable by nature of acquiring and which she experiences as always already in place, as something she and others agree in. In this respect, ordinary language is presented as natural for human beings, as a part of human nature: talking is the human form of life. The second initial contrast which establishes the significance of the phrase ordinary language is one reminiscent of Heidegger; for Wittgenstein, the ordinary is opposed to the philosophical - ordinary uses of words contrasted with philosophical ones. However, whereas Heidegger regards philosophers as having overlaid the true lineaments of ordinary experience with the prejudiced and partial categories of philosophical theorizing, Wittgenstein sees the dissatisfaction of philosophers with ordinary words and concepts as leading them to abandon them in favour of ones which they cannot fully mean, which are in effect empty. Philosophical uses of words are in this sense not redefinitions of them, not technical uses of terms, but ones in which they fail to mean anything. Philosophy is not an alternative set of language games but an attempt to speak outside language games; and its effect is not distortion or misrepresentation but nonsense. Thus the contrast is not between ordinary language and some other species of language, but between ordinary language and no language at all.

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

154

Stephen Mulhall

However, this interpretation of philosophical discourse as empty or not fully meant brings a question in its train. How do philosophers get into the position of wanting to violate grammatical rules, to speak outside the language games within which they are happy to conduct their day-to-day lives? What is it that fails to satisfy them about ordinary language when they are doing philosophy? If we read ordinary language as a synonym for natural language, the following answer would seem plausible: what disturbs them is precisely the naturalness of ordinary language, the fact that it is merely natural, a matter of humanlydetermined rules in which people (it seems) just happen to agree. For if grammar is what fixes the meanings of terms, and so forges the connection between words and the world, then that connection is only a function of human agreement, a matter of convention; and that seems to make both the nature and the fact of our grip on the world, our communion with it, entirely arbitrary and contingent. Why should we believe that the frameworks, the discourses, that are based upon such fragile and anthropocentric agreements do bring us into contact with the world as it really is; why should we believe that they establish any connection with reality at all? From this perspective we might see philosophical predilections for formal languages as attempts to gain a less arbitrary grip on the world (attempts which repress the fact that formal languages are no less a function of human agreement than any other symbolsystem), and see philosophical predilections for scepticism as expressions of the despairing belief that a merely natural grip on the world is no grip at all. For Wittenstein, it is undeniable that our grip on the world is most fundamentally a function of human agreement; indeed, what is valuable in scepticism is its refusal to accept the common sense view of the nature of our grip on the world - a view which regards that grip as most fundamentally cognitive, regarding the existence of material objects (for example) as something which we know for certain or in which we believe. Making knowledge claims about the world presupposes meaningful terms from which such claims can be constructed, and that presupposes rules or standards of correctness (rules of grammar) which fix those meanings. Formulations or expressions of those rules - what Wittgenstein calls grammatical remarks - specify the criteria of a given term by specifylng the circumstances in which it is correctly used, but since they do not themselves make claims about the world, they are not open to assessment in terms of evidence or justifiability; just as with any other species of rule, but unlike the knowledge claims which they make possible, the concepts of truth and falsity have no application to grammar. Since our capacity to know the world hinges upon the alignment of words and world which grammatical remarks elucidate, it follows that it is the nature of the fit of grammar with reality which most fundamentally illuminates the human relationship with the world; and that is simply a matter of human agreement in following or applying criteria. In the first place, however, this truth about the alignment of language with reality will hold for any and every meaningful use of language; if the existence of a grammatical framework must be presupposed by any intelligible discourse,

~~ ~

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

155

then reliance upon such a grammar is not something which can be avoided by anyone who wishes to say something, for the alternative is to fail to say anything meaningful at all. In short, the sceptic cannot avoid making use of some particular humanly agreed, conventional alignment of grammar and reality if he wants to speak; it is this indispensability of grammar which ensures that when he attempts to do without grammatical conventions - as Wittgenstein claims he is driven to do - he finds himself voiceless, not merely silent but incapable of speech. Moreover, on this reading of the role of grammar, the sceptic has no real reason to be dissatisfied with conventional alignments between words and world, no real reason to attempt to dispense with the indispensable. For a corollary of acknowledging that our relationship to the world is most fundamentally criteria1 is the fact that those criteria are not appropriate subjects of sceptical modes of anxiety. More precisely, if our relationship to the world on this level is not a cognitive one, then it cannot be vulnerable to the sorts of doubts or uncertainty that are standing threats to knowledge-claims. If a grammatical remark is not something that is capable of being true, it is also and simultaneously incapable of being false; so when an aspect of the grammar of a concept is pointed out, we cannot intelligibly suggest that this concept may nonetheless misrepresent the reality with which it is aligned. It makes no sense to suggest that the criteria which govern the concept of pain or of understanding may fail to capture the true nature of pain or understanding, because those criteria - by fixing what is meant by 'pain' or 'understanding' - fix what counts as pain or understanding; anything which fails to fit those criteria will not be an instance of pain or understanding, and anything which does will. In short, grammar tells us what kind of object anything is: essence is expressed by grammar - and this means that a grammatical investigation can reveal things about the nature of the world with which grammar aligns us. What the sceptic fails to appreciate about ordinary language is that its basis in convention and agreement, and so its contingency, does not make it untrustworthy; on the contrary, it also and by the same token makes it a source of insight into the reality with which it is aligned. It is precisely because grammar is not a description of the world that it can be relied upon not to misdescribe that world; it is precisely because there can be no question of justifying its fit with reality that ordinary language can be the final arbiter about the essential nature of that reality. The ordinariness of language is thus not something over which to despair because it is a mode of access to the ordinary world; its naturalness ensures that it is a mode of access to nature. This view of scepticism's despair as misplaced does not, of course, entail that Wittgenstein regards scepticism as simply erroneous or as easily extirpated. In the first place, if ordinary, natural language is 'merely' a function of human agreement, then scepticism - understood as an attempt to get beyond or to refuse such agreement - is and must be a standing possibility for human beings; anything that is essentially conventional must be vulnerable to the withdrawal of consent. In this respect, scepticism is the obverse of the ordinary, the

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

156

Stqhen Mulhall

ineradicable threat without which the ordinary would not be (merely) ordinary at all. Moreover, scepticism is an essential moment in the process of revealing the ordinary. In the philosophical tradition, sceptical arguments have the virtue of revealing as inadequate the commonsense view that human beings can know with certainty that the world exists by showing that such beliefs or knowledgeclaims are not justifiable, not based on evidence. Of course, this does not mean that the sceptic has proven that the world does not exist; all that it shows is that the existence of the world is not something that we can claim to know or believe, that we do not stand in a cognitive relation towards that world. The sceptic thus misinterprets a grammatical point - the inapplicability of the concepts of belief and knowledge in these contexts - as an empirical one - the absence of justification in a context which might seem to require it - and so shares in the mistake of the commonsense philosopher; but his attack upon the latter is essential in the sense that a correct understanding of our relationship to the world requires that we dispense with a commonsense understanding of that relationship. In this respect, scepticism is not just the essential obverse of the ordinary; it is only after the ordinary is subjected to sceptical attack that philosophy is in a position to reclaim it by re-conceiving our relationship to it. And of course, the reclaiming of the ordinary (both language and world) in Wittgensteins philosophical practice is not something which can be done once and for all. Every word in a natural language has its grammar, so the alignment of every word with the world is and must be open to the possibility of sceptical anxiety and despair; and recovery from one such bout of angst does not inoculate the sufferer from a future recurrence. In this respect, no part of ordinary language is immune to scepticism; so the process of recovering from such scepticism will be never-ending, a daily, repetitive task of bringing ordinary language back from the threat of self-destruction which is inherent in it and re-establishing an attitude towards it which allows the human beings who use it to acknowledge its naturalness without rejecting it. Wittgensteins goal is thus not that of establishing the priority of a particular segment or sort of language, but of continuously re-establishing an attitude towards language as such; his goal is the diurnal achievement of a mode o f inhabiting (ordinary) language which acknowledges it as a mode of inhabiting the (ordinary) world.

3. Author, Reader and Self-transformation:Perfectionist Writing

In claiming that the writings of Wittgenstein and Heidegger -both early and late of perfectionism that I have in mind is that developed by Stanley Cave11 in his Perfectionism writings on Emerson - what he calls Emersonian perfe~tionism.~ is a species of teleological theory, i.e. one that defines the good independently of the right, and defines the right as that which maximizes the good; and Emersonian perfectionism specifies that good as involving the state of the human soul. The soul is understood as being on an onward or upward journey

- can be thought of as examples of perfectionist writing, the understanding

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Wittgenstein and Heidegger: Orientations to the Ordinary

157

that begins when one finds oneself somehow spiritually disoriented, lost to the world, and that requires a refusal of the present state of society in the name of some further, more cultivated or cultured state of the self and of the self's society. Cavell's Emerson thus pictures both self and society as doubled or split: the self between its present, attained state and its next or further, unattained but attainable state; and society between its present state (which importantly contributes to the self's disorientation and its attachment to or fixation upon its present state) and a future state in which its arrangements more nearly approach an ideal of justice and so are more nearly capable of freely attracting the support of the selves that are its occupants and architects. This sort of perfectionism does not entail an idea of perfectibility, as if Emerson conceives of there being any given state of the self that is final in the sense of being unsurpassable rather than simply unsurpassed; for the duplexity of the self is ineliminable- each attainable state, once attained, reveals a further, at-present unattained state that neighbours it. However, each given or attained state of the self is final in another sense, for each constitutes a world that the self can and does desire, to which it is (and is always at risk of remaining) attached - a world that is, one might say, perfectly self-sufficient. If a given person so manages the relation of her attained to her unattained self that her desire does remain attached to or fixated upon its attained state, her position is one that Emerson labels 'conformity' - her unattained but attainable self is in eclipse, and so the possibility of personal growth, of the self continuing on its journey, is negated. Anyone in such a position stands in need of help if she is to reorient herself, to avert conformity: if her unattained self and its attractions are ever to eclipse that which at present eclipses them, someone else - someone free of her self-imposed and self-maintained darkness - must represent them to her and for her, must free her ear to hear their voice. This means, first, revealing that she is at present deaf to that voice, that she is reliant upon her attained self; and second, allowing her to realize that this present balance is her own responsibility, something that she maintains and so something that she has the power to overturn in favour of her unattained but attainable self. This interlocutor or friend is thus someone whose role is to resuscitate her autonomy by representing her next or further possibility. In Cavell's view, this role is one that Emerson himself takes on in the writing of his famous series of Essays; his role as their author is precisely to arrange and order his words so as to attract his readers to the next or further state of themselves and repel them from conformity with their present, attained state but to do so whilst preserving their autonomy, without merely substituting thralldom to their attained selves with thralldom to himself. Can a case be made for regarding this as a role that Wittgenstein and Heidegger understand themselves to be taking on? In order to see how Wittgenstein's later philosophical practice conforms to this model, we must think of the Wittgensteinian philosopher as someone who in

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

158

Stephen Mulhull

effect attempts to attract a given individual to a task of self-transformation. To begin with, Wittgenstein clearly understands philosophical violations of grammar to be a function, not of ignorance or error, and not of duplicity or mendacity, but of a spiritual confusion. This confusion is what he brings into focus when he claims that a philosophical problem takes the form of not knowing ones way about (PI, $j 123) i.e. that philosophy begins with a loss of orientation. This is, in the first instance a loss of orientation within language; but given the nature of criteria, it cannot be divorced from a loss or orientation within the world one inhabits and within oneself. Since, as we saw earlier, criteria alone permit us to differentiate between phenomena, and since they thereby give expression to our interest in phenomena (marking shared routes of interest in and reaction to the world, our sense of similarity, significance and outrageousness in its variations and combinations), then their refusal - in our philosophical attempts to speak outside language-games - is equivalent to stripping the objects that make up the world of their variegated specificity and value. In refusing criteria, we annihilate our world and our interest in it, transforming it and the lives we lead within it into an undifferentiated plenum; we thereby create a fixated, frozen and dead version of self, words and world. It is the task of the philosopher to encourage us to undo the disorder and unfreeze the fixation, to allow us to find our way on by finding our way back to our words, our world and ourselves. But this return to the ordinary is not necessarily a return to the status quo ante; it may be a return to an attitude to the ordinary that did not exist hitherto, and so must be thought of not so much as a return but as a turn - a turn to the (eventual) everyday whose terms are contained in the (actual) everyday. In coming, for example, to see that a pains being my pain is not a property of the pain but a fact about me (cf. PI, 5 253), we realize that the notion of private ownership of our pains is a piece of mythology which incoherently attempts to affirm our separateness as persons by attributing uniqueness to our experiences; and we might thereby come to grasp and to enact a conception of our relation to our own minds and to other persons that the ordinary grammar of psychological concepts always already delineated but which our ordinary lives did not always already embody. After all, Wittgenstein does call for a revolution in philosophy, and he does so by calling for the axis of reference of our investigation to be turned around the fixed point of our real need (PI, 5 108); in other words, his demand is for a species of conversion, and this conversion presupposes that we have falsely identified our need, that we are fixed or fixated upon a false need or a false conception of that need, and so upon a false conception of ourselves. And this is no once-for-all conversion, because - again as we saw earlier - the loss of orientation to which it is a response is something that can befall a speaker at any time in relation to any word; so the need to reorient us by recalling us to our criteria and our shared life with the words they govern is likely to arise endlessly, day-after-day, each successful return itself to be repeated on another occasion, and no one return being enough in itself to overcome the possibility of future refusals. In short, Wittgensteins practice is diurnal, positing no fixed or

@ Basil Blackwell Ltd. 1994

Вам также может понравиться

- Heidegger - What Is A ThingДокумент55 страницHeidegger - What Is A Thingcarsten_cozart_madsen5005Оценок пока нет

- The Involuntarist Image of ThoughtДокумент19 страницThe Involuntarist Image of ThoughtEser KömürcüОценок пока нет

- The Body Problematic: Political Imagination in Kant and FoucaultОт EverandThe Body Problematic: Political Imagination in Kant and FoucaultОценок пока нет

- Surprise: The Poetics of the Unexpected from Milton to AustenОт EverandSurprise: The Poetics of the Unexpected from Milton to AustenОценок пока нет

- Sellars Naturalism The Myth of The Given PDFДокумент29 страницSellars Naturalism The Myth of The Given PDFAlice FarmerОценок пока нет

- Sluga, Hans D. Frege's Alleged Realism - 1977 PDFДокумент18 страницSluga, Hans D. Frege's Alleged Realism - 1977 PDFPablo BarbosaОценок пока нет

- Unsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial ImaginationОт EverandUnsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial ImaginationОценок пока нет

- Searle and DerridaДокумент18 страницSearle and DerridaishisushiОценок пока нет

- Words Fail: Theology, Poetry, and the Challenge of RepresentationОт EverandWords Fail: Theology, Poetry, and the Challenge of RepresentationОценок пока нет

- Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of GivennessОт EverandBeing Given: Toward a Phenomenology of GivennessРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- A Custodian of Grammar: Essays on Wittgenstein's Philosophical MorphologyОт EverandA Custodian of Grammar: Essays on Wittgenstein's Philosophical MorphologyОценок пока нет

- Imaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the ImaginaryОт EverandImaginal Politics: Images Beyond Imagination and the ImaginaryОценок пока нет

- Eric Alliez-The Grace of The UniversalДокумент6 страницEric Alliez-The Grace of The Universalm_y_tanatusОценок пока нет

- Art of the Ordinary: The Everyday Domain of Art, Film, Philosophy, and PoetryОт EverandArt of the Ordinary: The Everyday Domain of Art, Film, Philosophy, and PoetryОценок пока нет

- The Brussels School of RhetoricДокумент28 страницThe Brussels School of Rhetorictomdamatta28100% (1)

- ADORNO en Subject and ObjectДокумент8 страницADORNO en Subject and ObjectlectordigitalisОценок пока нет

- Quine (1956)Документ12 страницQuine (1956)miranda.wania8874Оценок пока нет

- Cut of the Real: Subjectivity in Poststructuralist PhilosophyОт EverandCut of the Real: Subjectivity in Poststructuralist PhilosophyОценок пока нет

- Complexul OedipДокумент6 страницComplexul OedipMădălina ŞtefaniaОценок пока нет

- Bruno Bosteels - Force A Nonlaw Alain Badiou's Theory of JusticeДокумент22 страницыBruno Bosteels - Force A Nonlaw Alain Badiou's Theory of JusticemanpjcpОценок пока нет

- Lecture 4: From The Linguistic Model To Semiotic Ecology: Structure and Indexicality in Pictures and in The Perceptual WorldДокумент122 страницыLecture 4: From The Linguistic Model To Semiotic Ecology: Structure and Indexicality in Pictures and in The Perceptual WorldStefano PernaОценок пока нет

- Hans-Georg Gadamer Philosophical Hermeneutics 1977-Pages-59-99 UntaintedДокумент41 страницаHans-Georg Gadamer Philosophical Hermeneutics 1977-Pages-59-99 UntaintedJUNAID FAIZANОценок пока нет

- Inheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertОт EverandInheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertОценок пока нет

- Conant (1998) Wittgenstein On Meaning and UseДокумент29 страницConant (1998) Wittgenstein On Meaning and UseMariane Farias100% (1)

- Resistance and the Politics of Truth: Foucault, Deleuze, BadiouОт EverandResistance and the Politics of Truth: Foucault, Deleuze, BadiouОценок пока нет

- Bottici Imaginal Politics 2011Документ17 страницBottici Imaginal Politics 2011fantasmaОценок пока нет

- Against Flat OntologiesДокумент17 страницAgainst Flat OntologiesvoyameaОценок пока нет

- Nico Baumbach Jacques Ranciere and The Fictional Capacity of Documentary 1 PDFДокумент17 страницNico Baumbach Jacques Ranciere and The Fictional Capacity of Documentary 1 PDFCInematiXXXОценок пока нет

- Rudolf Carnap - The Logical Structure of The World - Pseudoproblems in Philosophy-University of California Press (1969)Документ391 страницаRudolf Carnap - The Logical Structure of The World - Pseudoproblems in Philosophy-University of California Press (1969)Domingos Ernesto da Silva100% (1)

- Zahurska - From Narcissism To Autism: A Digimodernist Version of Post-PostmodernДокумент8 страницZahurska - From Narcissism To Autism: A Digimodernist Version of Post-PostmodernNataliia ZahurskaОценок пока нет

- Asubjective PhenomenologyОт EverandAsubjective PhenomenologyĽubica UčníkОценок пока нет

- Derek Attridge - The Work of LiteratureДокумент30 страницDerek Attridge - The Work of Literaturehijatus100% (2)

- (Suny Series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy) David Farrell Krell - Ecstasy, Catastrophe - Heidegger From Being and Time To The Black Notebooks (2015, State University of New York Press) PDFДокумент222 страницы(Suny Series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy) David Farrell Krell - Ecstasy, Catastrophe - Heidegger From Being and Time To The Black Notebooks (2015, State University of New York Press) PDFpsolari923Оценок пока нет

- Books 401: Rockhurst Jesuit University Curtis L. HancockДокумент3 страницыBooks 401: Rockhurst Jesuit University Curtis L. HancockDuque39Оценок пока нет

- The Work of Difference: Modernism, Romanticism, and the Production of Literary FormОт EverandThe Work of Difference: Modernism, Romanticism, and the Production of Literary FormОценок пока нет

- Levinas and the Trauma of Responsibility: The Ethical Significance of TimeОт EverandLevinas and the Trauma of Responsibility: The Ethical Significance of TimeОценок пока нет

- Itinerant Philosophy: On Alphonso LingisДокумент191 страницаItinerant Philosophy: On Alphonso LingisEileen A. Fradenburg Joy100% (2)

- Dreyfus OVERCOMING THE MYTH OF THE MENTAL How PHILOSOPHERS CAN PROFIT FROM THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF EVERYDAY EXPERTISEДокумент20 страницDreyfus OVERCOMING THE MYTH OF THE MENTAL How PHILOSOPHERS CAN PROFIT FROM THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF EVERYDAY EXPERTISEAndrei PredaОценок пока нет

- Cora Diamond - "The Difficulty of Reality and The Difficulty of PhilosphyДокумент27 страницCora Diamond - "The Difficulty of Reality and The Difficulty of PhilosphyMiriam Bilsker100% (1)

- The Darkness of the Present: Poetics, Anachronism, and the AnomalyОт EverandThe Darkness of the Present: Poetics, Anachronism, and the AnomalyОценок пока нет

- Husserl On. Interpreting Husserl (D. Carr - Kluwer 1987)Документ164 страницыHusserl On. Interpreting Husserl (D. Carr - Kluwer 1987)coolashakerОценок пока нет

- Hermeneutical Approach to Everyday AestheticsДокумент20 страницHermeneutical Approach to Everyday AestheticsinassociavelОценок пока нет

- Christopher Kueffer Ten Steps To Strengthen The Environmental HumanitiesДокумент5 страницChristopher Kueffer Ten Steps To Strengthen The Environmental Humanitiesrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- A Philosopher of Nonviolence Aldo CapitiniДокумент17 страницA Philosopher of Nonviolence Aldo CapitinirustycarmelinaОценок пока нет

- Messiaen's Musico-Theological Critique of Modernism and PostmodernismДокумент28 страницMessiaen's Musico-Theological Critique of Modernism and Postmodernismrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Theology East and West - Difference and Harmony Lawrence CrossДокумент11 страницTheology East and West - Difference and Harmony Lawrence Crossrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Christopher Dawson Religion and Culture IДокумент19 страницChristopher Dawson Religion and Culture Irustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- McEvilley An Archeology of Yoga 1981Документ35 страницMcEvilley An Archeology of Yoga 1981rustycarmelina108100% (2)

- Cyclothymia, A Circular Mood Disorder by Ewald Hecker Introduction by Christopher Baethge, A, B Paola Salvatoreb, C and Ross J. BaldessarinibДокумент15 страницCyclothymia, A Circular Mood Disorder by Ewald Hecker Introduction by Christopher Baethge, A, B Paola Salvatoreb, C and Ross J. Baldessarinibrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Christopher Dawson, Historian of Christian Divisions and Prophet of Christian UnityДокумент14 страницChristopher Dawson, Historian of Christian Divisions and Prophet of Christian Unityrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Corwin - Higher Law Pt.1Документ37 страницCorwin - Higher Law Pt.1areedadesОценок пока нет

- Heidegger - Heraclitus SeminarДокумент92 страницыHeidegger - Heraclitus Seminarrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Love, Open Awareness, and Authenticity - A Conversation With William Blake and D. W. WinnicottДокумент28 страницLove, Open Awareness, and Authenticity - A Conversation With William Blake and D. W. Winnicottrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- The Fall of Fantasies - A Lacanian Reading of LackДокумент27 страницThe Fall of Fantasies - A Lacanian Reading of Lackrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Meridians, Chakras and Psycho-Neuro-Immunology - The Dematerializing Body and The Domestication of Alternative Medicine JUDITH FADLONДокумент19 страницMeridians, Chakras and Psycho-Neuro-Immunology - The Dematerializing Body and The Domestication of Alternative Medicine JUDITH FADLONrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- What Is Platonism, Lloyd GersonДокумент23 страницыWhat Is Platonism, Lloyd Gersonrustycarmelina108100% (2)

- Breathing The Aura - The Holy, The Sober BreathДокумент21 страницаBreathing The Aura - The Holy, The Sober Breathrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Wittgenstein's Family Resemblances and the Open Concept of ArtДокумент4 страницыWittgenstein's Family Resemblances and the Open Concept of Artrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Objects and Spaces John LawДокумент16 страницObjects and Spaces John Lawrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Wittgenstein's Family Resemblances and the Open Concept of ArtДокумент4 страницыWittgenstein's Family Resemblances and the Open Concept of Artrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Sociology of The Heart Max Scheler's Epistemology of LoveДокумент36 страницSociology of The Heart Max Scheler's Epistemology of Loverustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Messiaen's Musico-Theological Critique of Modernism and PostmodernismДокумент28 страницMessiaen's Musico-Theological Critique of Modernism and Postmodernismrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Love, Open Awareness, and Authenticity - A Conversation With William Blake and D. W. WinnicottДокумент28 страницLove, Open Awareness, and Authenticity - A Conversation With William Blake and D. W. Winnicottrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- The Reassembly of The Body From Parts - Psychoanalytic ReflectionsДокумент36 страницThe Reassembly of The Body From Parts - Psychoanalytic Reflectionsrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Christopher Dawson, Historian of Christian Divisions and Prophet of Christian UnityДокумент14 страницChristopher Dawson, Historian of Christian Divisions and Prophet of Christian Unityrustycarmelina1080% (1)

- Women Showing Off Notes on Female ExhibitionismДокумент25 страницWomen Showing Off Notes on Female Exhibitionismrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Wisdom and DevotionДокумент6 страницWisdom and Devotionrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- The Message of Islam Abdelwahab BouhdibaДокумент7 страницThe Message of Islam Abdelwahab Bouhdibarustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- The Language of Empathy - An Analysis of Its Constitution, Development, andДокумент29 страницThe Language of Empathy - An Analysis of Its Constitution, Development, andrustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- AtmanandaДокумент518 страницAtmanandarustycarmelina108100% (1)

- The Most Secret Quintessence of Life by Chandak SengooptaДокумент4 страницыThe Most Secret Quintessence of Life by Chandak Sengooptarustycarmelina108Оценок пока нет

- Varthis Columbia 0054D 13224Документ100 страницVarthis Columbia 0054D 13224MARLON MARTINEZОценок пока нет

- The Brown Bauhaus STUDIO ARCHITECTURE: Fundamental Course - Comprehensive Ale Review + Preparation ProgramДокумент10 страницThe Brown Bauhaus STUDIO ARCHITECTURE: Fundamental Course - Comprehensive Ale Review + Preparation ProgramClaro III TabuzoОценок пока нет

- Learning Analytics in R With SNA, LSA, and MPIAДокумент287 страницLearning Analytics in R With SNA, LSA, and MPIAwan yong100% (1)

- Readiness of Junior High Teachers for Online LearningДокумент72 страницыReadiness of Junior High Teachers for Online LearningSheila Mauricio GarciaОценок пока нет

- Reading and Writing StrategiesДокумент76 страницReading and Writing StrategiesGerrylyn BalanagОценок пока нет

- Theories and Models in CommunicationДокумент19 страницTheories and Models in CommunicationMARZAN MA RENEEОценок пока нет

- Visionary CompassДокумент77 страницVisionary CompassAyobami FelixОценок пока нет

- Perl Mutter's EPRG Model & Hoff's TheoryДокумент14 страницPerl Mutter's EPRG Model & Hoff's Theorytrupti50% (2)

- Grade 1 - EVS Lesson Plan - People Who Help UsДокумент3 страницыGrade 1 - EVS Lesson Plan - People Who Help UsNisha SinghОценок пока нет

- Sekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Seksyen 1 Bandar Kinrara 47180 Puchong, Selangor. Annual Scheme of Work 2016Документ9 страницSekolah Menengah Kebangsaan Seksyen 1 Bandar Kinrara 47180 Puchong, Selangor. Annual Scheme of Work 2016Vr_ENОценок пока нет

- Guidelines For Preparation and Presentation of SeminarДокумент2 страницыGuidelines For Preparation and Presentation of SeminarVenkitaraj K PОценок пока нет

- Teacher Evaluation in NsuДокумент23 страницыTeacher Evaluation in Nsumd shakilОценок пока нет

- FS 1 Episode 7Документ4 страницыFS 1 Episode 7Mike OptimalesОценок пока нет

- Math2 - q1 - Mod2 - Givestheplacevalueandfindsthevalueofadigitin3digitnumbers - Final (1) .TL - enДокумент24 страницыMath2 - q1 - Mod2 - Givestheplacevalueandfindsthevalueofadigitin3digitnumbers - Final (1) .TL - enRogel SoОценок пока нет

- Paper 1: Organization & Management Fundamentals - Syllabus 2008 Evolution of Management ThoughtДокумент27 страницPaper 1: Organization & Management Fundamentals - Syllabus 2008 Evolution of Management ThoughtSoumya BanerjeeОценок пока нет

- Dissociative Identity DisorderДокумент23 страницыDissociative Identity DisorderSania Khan0% (1)

- Teaching With Contrive Experiences Teaching With Dramatized Experiences Aladin M. Awa - ReporterДокумент6 страницTeaching With Contrive Experiences Teaching With Dramatized Experiences Aladin M. Awa - ReporterGaoudam NatarajanОценок пока нет

- Group Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementДокумент3 страницыGroup Assignment Topics - BEO6500 Economics For ManagementnoylupОценок пока нет

- Network Traf Fic Classification Using Multiclass Classi FierДокумент10 страницNetwork Traf Fic Classification Using Multiclass Classi FierPrabh KОценок пока нет

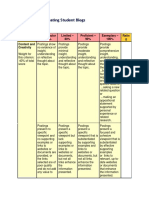

- A Rubric For Evaluating Student BlogsДокумент5 страницA Rubric For Evaluating Student Blogsmichelle garbinОценок пока нет

- Fast Underwater Image Enhancement GANДокумент10 страницFast Underwater Image Enhancement GANVaishnavi S MОценок пока нет

- GTGC-RID-OP-FRM-24 Employee Annual EvaluationДокумент2 страницыGTGC-RID-OP-FRM-24 Employee Annual EvaluationDanny SolvanОценок пока нет

- Detecting Stress Based On Social Interactions in Social NetworksДокумент4 страницыDetecting Stress Based On Social Interactions in Social NetworksAstakala Suraj Rao100% (1)

- FrontmatterДокумент9 страницFrontmatterNguyen ThanhОценок пока нет

- Write To Heal WorkbookДокумент24 страницыWrite To Heal WorkbookKarla M. Febles BatistaОценок пока нет

- The Power of Music in Our LifeДокумент2 страницыThe Power of Music in Our LifeKenyol Mahendra100% (1)

- Review of The Related Literature Sample FormatДокумент4 страницыReview of The Related Literature Sample FormatBhopax CorОценок пока нет

- CS UG MPE 221 Flid Mech DR Mefreh 1Документ5 страницCS UG MPE 221 Flid Mech DR Mefreh 1Mohamed AzeamОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan in Physical EducationДокумент4 страницыLesson Plan in Physical EducationGemmalyn DeVilla De CastroОценок пока нет

- A Long EssayДокумент2 страницыA Long EssaysunnybakliwalОценок пока нет