Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Argentine Intellectuals and Homoeroticism

Загружено:

Patricio PérezАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Argentine Intellectuals and Homoeroticism

Загружено:

Patricio PérezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Argentine Intellectuals and Homoeroticism: Nstor Perlongher and Juan Jos Sebreli Author(s): David William Foster Source:

Hispania, Vol. 84, No. 3 (Sep., 2001), pp. 441-450 Published by: American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3657778 . Accessed: 30/01/2014 08:06

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hispania.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTELLECTUALS AND HOMOEROTICISM 441

Argentine Intellectuals and Homoeroticism: Nestor Perlongher and Juan Jose Sebreli

DavidWilliamFoster ArizonaState University

Abstract: The returnin 1985to constitutional democracyin Argentina broughtwithit manysocial changes, of the city of BuenosAires in 1996 includingthe beginningsof a lesbigayrights movement.The constitution institutionalized the rights of sexualpreference. This studyexaminesthe writingsof three Argentineintellectualswhose workon homoeroticism is partof a morefavorable climatefor the legitimation of homoeroticdesire in Argentina, especiallyin BuenosAires. Keywords: Argentina(social aspects), Buenos Aires (social aspects), Lesbigayrights, Homoeroticdesire, Historyof homosexuality, Argentineessay

I In 1996,the city of BuenosAires,having been accordeda politicalidentityseparate fromthatof being the DistritoFederal,and therefore without a governing autonomy that would allow it to address directly its only sociopoliticalissues, adopted a constitution. Article 11 of that constitution reads:

Se reconocey garantiza el derechoa ser diferente,no admitiendose discriminaciones que tiendan a la segregaci6nporrazoneso con pretextode raza,etnia, genero, orientaci6n sexual, edad,religi6n,ideologia, caracteresfisicos, condici6n opini6n,nacionalidad, psicofisica, social, econ6mica o cualquier circunstancia que implique distinci6n, exclusi6n, restricci6no menoscabo.

Such a guarantee can hardly begin to scratchthe surfaceof a long history of homophobia in Argentina and, more to the point,of a longhistoryof policepersecution: police edicts regardingpublicdecency still remainin effect,andpublicdisplays(including on occasionactivitiesin the semiprivate space of bars and clubs) of homoerotic manifestation and affectioncontinueto be more than sporadically harassed. It is one of the great ironies of contemporary life in Buenos Aires that, while men of all social classes have adoptedthe practiceof social kissing (on the cheek, of course, and usually in only a feigned fashion), along with

the corporal andcasualtouching proximity that is a characteristicof Mediterranean culture, there remains a very clear consciousness of when such body language remainswithinthe orbitof the confirmation of heterosexist masculinity and when it threatens to transgress the boundariesof that orbit; and such a consciousness remains firmly committed to maintaining those boundaries in the sociallifeof the city. It is not difficult, however,to understand how recognitionof the rights of sexual difference could have entered into the final text of the constitution. It is the consequence of the activitiesof myriadorganizations in supportof homosexualrights and dignitythatextend back, at least in a political movement sense, to the early 1970s (which means that the members of such groups were includedin the persecutions and oppressionsof politicaldissidencedurafter1976), dictatorships ing the neo-fascist as much as it is the influenceinporteiiolife of the abiding criterion, "On doit &tre absolumentmoderne": if lesbigay rights is a prominent featureof the postmodern, neoliberal, late capitalistmetropolis, as modeled by U.S. andWesternEuropeancities, thanit mustalso be so in the case of Buenos Aires. (ThatSantiagode Chile,once touted, but during the grim days of post-military still economicallydepressedlife in Buenos model for the SouthAires, as a neo-liberal

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2001 442 HISPANIA 84 SEPTEMBER

ern Cone, continues to be one of the most stridently homophobic capitals of Latin Americais not lost on its Argentine rival, which feels that it has handilyoutstripped the Chileanexample.) But one cannotbe content simplyto assume that lesbigay rights in Argentinaare the consequence of its energetic participanorthe late capitalism, tion in international beneficiaryof a spectrumof citizen rights that, as a long-overduedebt, has been presented for paymentto the politicalprocess as partof whatremainsof the projectof the ofArgentinesociety.Just redemocratization as movementpoliticsof anystripeare associated with variousintersectingcollaborations or involvementswith theoreticaldiscourse specificallyand culturalproduction in general, one may refer to the extensive arrayof fiction,theater,and film (andalso, to a lesser extent,because it circulatesless extensively, poetry) that has come out of Argentinain recent decades that is lesbigay/queer markedthatmodelshomoerotic lives andissues (includinghomophobicrepression and persecution), one may also refer to an importantintellectual activity that has served to create, through principled analysis, a reflective discourse regarding homoeroticism. Thus, one can writerslike ManuelPuig pointto important (the only one to have gained international Pizarnik(who is now attention),Alejandra for receivingconsiderablecriticalattention the lesbian elements of her work), Oscar Hermes Villordo,Juan Maria Borghello, Juan Jos6 Hernindez, H6ctor Lastra, RenatoPellegrini, Manuel MujicaULinez, ReinaRoff6,to name only a few. Films like EnriqueDawi'sAdids,Roberto(1985) and AmericaOrtizde ZArate's Otrahistoriade amor (1986), along with those of Maria LuisaBemberg (Lasetiorade nadie [1982],

[1993]), provide an impressive list where one can begin to examine a cultural record of issues of same-sex identity and the repudiation of compulsory heterosexuality in

Argentina.1

II

These works are written against the dimensionsof sexual of important backdrop ideology in Argentinathat can be characterized in the following terms.2Although Argentinadiffersfrom other LatinAmerican societies in whichthe conceptof nation emerged under the aegis of militaryinstiCuba tutions (e.g., Chile or revolutionary since 1959), the Argentine independence movementwas led by burghersdissatisfied with Spanish centrist controls over commerce.Argentinesocialhistoryhas, in fact, been dominated which,like by the military, conthe Catholic Church,havetraditionally institutions.Argenstituted quasi-political tinahad its first militarycoup only in 1930, andthe political life of the countryhas been dominated ever since by an overtly masculinistinstitutionthat has repeatedly assumed control over the government in order to safeguardand enforce ideologies associated with male privilege, including those of gender, class, and ethnicity. As a consequence, a strongand explicit version of homophobiahas long charactertext of izedArgentinesociety.The founding Argentine fiction, Esteban Echeverria's long short storyEl matadero(OheSlaughterhouse), which was probablywrittenin 1839butnotpublisheduntil1874,endswith a homosexualrapescene, as maleagentsof one politicalfactionassert its authority by attackingthe body of what they take to be In of the opposition. a token representative overan that Echeverria'sstory, it is clear determinedschism betweenpoliticalagendas includes an over-determined physical aggression againsta token body of the oprapeis a legitipositionin which male-male mate form of social control and an intelligible assertion of the superiorityof one and Yo,la peor de todas [1990], De eso no se habla bandthanksto its abilityto "feminize"

penetrate an exemplar of the opposing band (in the story, the victim asserts, in turn, his moral superiority by willing his own elliptic-like death rather than submit to the humiliating invasion of his body by his tormentors). Echeverria's story, in addition to inaugu-

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTELLECTUALS AND HOMOEROTICISM 443

of narrative rating(alongwiththe tradition fiction in Argentina, and one insistently markedby politicalanalysis)the representationof political in termsof masdifference culine vs. feminine, sexual aggressor vs. sexual victim,mastervs. slave, articulates whatcontinuesto be a dominant sexualideology in Argentina: the Mediterranean scheme whereby the inserter retains his masculineandheterosexistprivilege.It can neverbe a questionfor the politicaltoughs in El matadero that they will become feminizedor homosexualized the by penetrating body of anotherman while the insertee is, by the act of subjugation, rape,and attending signs of humiliation, feminized and made a sexually deviant, and therefore scornful,body,one lackingin masculinist/ heterosexistauthority andbearingthe sign of the loser in the strugglefor politicalsurvivalandauthority. The culturalreflexes of this strain in Argentina have yet to be trackedandanalyzedadequately, although novelist and cultural theoretician David Vifiashas mademanysuggestions on what texts and aspectswill have to be takeninto accountin such a study. Thatthe toughsin Echeverria's storyare associated with the paramilitary forces of the early nineteenthcentury underscores how homophobiain the Argentinemilitary traditionhas includedliteraland displaced male-malerapeas a strategyof ideological control. Recent scandals concerning the of recruitseven duringthe period treatment followingthe returnto democracyand attempts to restructure military authority haveled bothto the abandonment of universal conscription and the introduction of women into a new careerarmy. Referencesto the recordof homophobia in Argentina,while they can be teased out of the culturalrecord prior to the 1950s, become increasingly explicit beginning

Process of National Reconstruction, asserted the primacyof the well-constituted Catholic, patriarchal family, and sexual moreswere of specialconcernto its agents. Relyingon the concept of public decency, ratherthanpersonalsexual acts (although it was assumed that lapses in public decency were to be equatedwith pernicious privatebehavior),the militaryregime persecuted an arrayof signs thatit considered to be evidence of sexual deviancy,one mato homojorclusterof whichwas attributed unsoberclothing,long hair,overt sexuality: toward body language,manifestpartialities certain types of music in certain types of public or semi-clandestine spaces, and a generallynon-masculinist persona. The stridencyof police persecutionand the repeatedwillingnessto confusegender and deviancywithpoliticalinsubordination even revolutionary conduct (homosexuals joinedwomen andJews in receivingsadistically enhancedforms of tortureafter detention) led eventuallyto the inclusionof a specificallygay and lesbian componentin the publicstruggleof resistanceagainstthe intrusionintoeveryaspectof permilitary's sonalandpubliclife.The ArgentineFrente de Liberaci6n Homosexual had been foundedin 1971 and dissolved at the time of the 1976 coup, but its leaders and new elements regroupedas partof the protest movements gaining public supportin the early 1980s. The Comunidad de of HomosexualesArgentinos[Community Argentine Homosexuals] must work through the period of the transition to constitutionaldemocracyin 1981, eventually winningthe nominalsupportof President CarlosMenemin the early1990s,with descendants the resultthat its present-day have managed to amass a considerable amountof symbolic,if not directlypolitical, fifteenyearsintothe current period support with the second presidency of Juan of institutional normalcy. At the present moment, the majorconDomingo Per6n (1952-55). Per6n was a military man who is, in turn, overthrown by cern amongArgentinegays andlesbiansis the military, which attains insistent force in forthe rightto publicvisibility, leincluding the context of the so-called Dirty War gitimatecivilstatusforthe recipientsof sex against subversion after the military coup change operations. AlthoughBuenosAires

in 1976. This coup, which established the has numerous gay bars and openly sold

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2001 444 HISPANIA 84 SEPTEMBER

locationsandactiviadvertising publications ties (andit should be noted that,in Argentina "gay"includes lesbians and that, deandhistoricaldifferpolitical spiteprofound ences, there is a sustained attempt at a united front), public gayness continues to be harassed by the police, often violently, and gay meeting places are extremelycircumscribed as to their from-the-street identification. Visibility here means the freedom to manifestgayness publiclyin a way that would bring the rights of bodies into conformancewith current rights for cultural products,at least as far gay-marked as publications,film, theater, and the like go; sex shops andtheiraccoutrementsstill remainbannedunderthe same concept of publicdecency that affectsgay bodies. As regardssex change operations, while of them appear the majority to be performed abroad(a clinic in Chile is often spoken of and has been featuredon at least one television program),a police edict still in force regarding public decency penalizes individualsfor the act of cross-dressing,and individualshave been unsuccessful in approachingthe CivilRegistryto have their sexual identity and, usually, their official name, altered, which forces them to continue to use a registrationcard that identifies them as a man, includingan appropriately attiredphotographic image. It shouldbe notedthatthe intense interest in transgendering continuesto reiterate the ideology whereby homosexualityis a matter of the passive or the insertee, and thus the identification of oneself as a homosexual means reinscription as a woman. Nevertheless, Argentinais a countrywith a long traditionof Freudianand Lacanian psychoanalysis, and alternative, more of homosexu"medicalized" interpretations ality exist, runningthe gamut from homosexual machos (a 1995 controversy over whether or not there were homosexuals in the national all-stars soccer team) to efforts at a gay politics that emulate North American projects of modern identity and projects of postmodern categorial transgression. The prospects for gay liberation are very good in Argentina, beginning with a very

good recordin the suspensionof the moral censorship of cultureand the possibilities that the neoliberaleconomy offers for the In of alternate subjectivities. empowerment seems willingto make this sense, Argentina constitutional guargood on the traditional antees of the sovereigntyof the body. Yet of hothere remainsa virulentsubstratum mophobiathatevinces itself as much in rethe of gay-bashing, curringmanifestations absence of institutional guaranteesfor individualspubliclymarkedas gay, and in the persistentveil of silence in mostquartersof anythinghavingto do withthe homoerotic. The purposeof this essay, however,is to examine the writingof a series of intellecthatcan be commentators tualsandcultural claimedto constitutea recordof reflective discourse on homoeroticissues in Argentina, even when some of the texts may be the workof individuals writingfromexile or forreasonsof the neohavebeen published, and other adfascist militarydictatorships verse circumstances,only years aftertheir originalcontribution. III N6stor Perlongher (1949-92), for example,wrote manyof his most memorable texts during the many years he spent in Brazil, where he studied and then later Althoughnow taught social anthropology. considereda major poet,his docArgentine toral dissertation, O negdcio do mich,: prostitui?doviril em Sao Paulo (1987) is perhapsthe best knowntreatiseon homosexualityin LatinAmerica.In 1987he also publishedin PortugueseO quee AIDSand in 1988in Spanish,Elfantasmadel SIDA,I believe the first such materials in both languages. O neg6ciodo michewas subsequentlypublished,with a postscriptby the in Argentina in 1993withthe titleLa author,

prostitucidn masculina. Negdcio, therefore, can be said to have had an important distribution precisely at a time when the lesbigay movement in Argentina had acquired con-

it is not a siderablemomentum.Certainly, to Perto attribute of question attempting influence longheranyspecificdetermining

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTELLECTUALS AND HOMOEROTICISM 445

norto saythatspecificideologicalpositions to characterize the sort of proletarian, or scholarlyopinionsof his contributed to plebian lives Perlongher was particularly wherethe conqualities or practicesof a movementthat, interestedin characterizing, afterall, given the scope of Argentinesoci- struction of desire cannot be neatly ety,has hardlyspokenwithone voice.Rath- disentwinedfromthe urgencyto survive. er, my pointwouldbe that Perlongherwas Moreover, Perlongher introduces into there as somethingof an eminence grise of his analysis a question of class consciousthose involved a manwho ness thatis oftensubmergedin discussions in the movement, had been on the battle-linesof the original of homoeroticism,especiallysince the bibFrentede Liberaci6n whohad liographyof class analysis itself has tradiHomosexual, whenit has gone into exile in Brazilbecause of the po- tionally ignoredhomoeroticism, litical climate in Argentina,who had par- not been aggressivelyhomophobic. Perlontaken deeply of the much richergay life in gher, however, pursues class along two Brazil's major cities, and who had been lines. One is that between the michesand among the first scholars in LatinAmerica their clients, which involves both the to actuallyconductscientifically-grounded conventional issue of class exploitation, researchthat could be cited in the attempt those who can purchasethe bodies of othto change the legal and social circum- ers and make demands upon them made stances of homoeroticdesire. possible by that purchase.A complemenChristianFerrerand OsvaldoBaigorria taryquestionconcernsthe strategiesof recall Perlonghera "pensador (8), sistance, defense, and even survival by callejero" in their recent selection of Perlongher's those purchasedin the face of the expectawritings, significantlytitled Prosaplebeya. tions and demands of the purchasers.On By this they mean to underscore how anotheraxis, however,Perlongheris interworkwas notjust "about" Perlongher's gay ested in the relationsamong the hustlers, life, but was "inthe life."Negdciohas been and it is here where he attemptsto chart criticizedfor romanticizing to a certainex- practices of homoerotic desire that arise tent the lives of male hustlers. Certainly, fromlived experiencesthat go beyondthe thereis an important to be made icon of the lone individual distinction selling his body between hustlerswho workthe streets be- to survive,and his investigationis thus imcause they have a need for sex with other portantfor the characterizationof public men and hustlerswho workthe streetsbe- aspects of homosexuality(vitalin the conit'sa livingand text of the issue of sexual decency in Latin cause, like most prostitutes, nota project of desire.Clearly, Perlongher's Americansocieties) and the fetishizing of research was of a whole with his own rough trade. If Perlongher'sstudy can be projects of desire, and one would not be faultedfor not adheringstrictlyto a rigorsurprisedto learnthathe ended up writing ously scholarly standard of sociological a dissertationon this topic because it was analysis(forexample,it is blessedly free of one with which he was alreadyintimately statistical charts),its valueas anintellectual familiar. But the theoretical point to be documentlies with the desire to question raised aboutNegdciois the problemof dis- implicitlythe Othering that is implied by tinguishingbetween sex for money (which scientific analysis and, more importantly, wouldlead to the conclusionthatthe street the a priori categories regarding sexual hustlers are not "gays" in any useful sense identitiesthe dialectical analysisof whichis

of the term) and sex for desire (in which hustling is part of a narrativeof desire). The need to maintaina distinction between prostitution and desire may satisfy certain ideological parameters (e.g., a middle-class gay movement grounded on a rhetoric of the boy next door), but it may not serve well so crucial a question of queer scholarship. Ferrer-Baigorria cites an anecdote that serves eloquently to underscore Perlongher's conceptual positioning with regard to discussing gay lives: "Unavez, en medio de una charla entre militantes de izquierda alguien quiso ser sarc istico en su

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

446 HISPANIA 84 SEPTEMBER 2001

comentario respectoa un chicode apariencia unamujer, equivoca: 'pero ?ese es unhombre, o qu'?' Parece que Perlongher habria (9). respondido:'Es qu&"'

IV

JorgeSalessi,who has livedin the United States since 1976, has the advantageof a inAnglo-American culthoroughgrounding turalstudies,whichrepresentsa synergetic intersection between traditional literary studies and pertinent theoretical dimensions drawnfromthe social sciences. Like with gay culPerlongher,his participation ture in Argentina has not been on a sustaineddailybasis. However,the publication in 1995 in Argentinaof his Midicos maleantes y maricas; higiene, criminologia y homosexualidaden la construcci6nde la naci6n Argentina. (Buenos Aires: 18711914), by BeatrizViterboEditora,one of the country's majornew publishers, specializingin literaryand culturalinterpretaless betion, is of tremendousimportance, cause of anyinnovative scholarly theorizing by Salessi than because of the detailed analysis of an importantcorpus of materials dealingwithsexualideology inArgentina the periodof nation formation. during Salessi's point of departureis the enormous concern for sexual hygiene that is a part of social discourse, specificallyin its medicalandlegal dialects,beginningin the late nineteenthcentury.Onewillrecallthat Foucault makes the important point throughoutthe firstvolume of A Historyof Sexualitythat the period of the high bourgeoisie thatcomes to powerin the latterhalf of the nineteenthcentury,far from silenca discussionof sexuality, ing, "repressing," in fact creates a substantialpublicvoicing of sexual issues as partof the regulationof

social institutions and their private dimensions and as the projection onto the many understandings of sex of a scientific analysis of sexuality/sexology consonant with the hegemonic ideologeme of Science of the period. Although the period can allegedly be important in many societies in the West, including the Americas, the period is

of special interestin a countrylike Argentina, because of the particular urgency of creating a modern society after the long interlude of civil war following independence andthe RosasTerror(Parker makes a similarpointfor Brazilbecause of the dividing line of the pre-modernEmpireand the declaration of the republic in 1889). Thus, the overallneed for establishingan orderof socialhygiene,of whichthe sexual is but one dimension,in Argentinais compoundedby the need to overcomewhat is viewed as the social disorderof the immediate past. As is well known, the Argentinenation builderssoughtthe best of modernscience in the pursuitof theirgoals, and it is therefore no surpriseto finda confluenceof concerns drawnfrom medicine, criminology, and pertinentsocial sciences that sustain the beginningsof an indigenousbibliography devoted to sexual concerns. Moreover--and it is herewhereSalessi'sspecific researchcomes into play-it is no surprise to find a series of publicscandalsused as a pretextfor the creationof a consciousness of a "socialproblem"and the call for the of appropriate measures,drawn application from the disciplines contributing to a dominantsexual ideology,to deal with the as one of social hygiene. "problem" Salessi chooses the ab quoyear 1871 as the period of the first modern plague in Argentina,a yellowfever epidemic;1914is the year of the first performanceof Jose GonzAlez Castillo'sLos invertidos, the first Argentinetheatricalwork to deal directly with homosexualityas a "socialproblem": homosexuality now enters the realm of mainline cultural production, no longer confinedto a popular discourseof the street or to that of modern science. (It is important to note that Los invertidos was republished in 1991and restagedby AlbertoUre in such a way as to open up Gonzdlez

Castillo's hysterical homophobic presuppositions, which are, of course, the very ones that circulate through the texts that Salessi analyzes; for recent research on GonzAlez Castillo's play, see Geirola; Foster.) By undertaking a detailed interpretive

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTELLECTUALS AND HOMOEROTICISM 447

analysis of archival documents and pub- in his nativecountrythanJuanJose Sebreli lished sources, manyof whichhavehad no (1930). Sebreli published in 1983, at the democcurrencyfordecades,Salessiengages in an time of the returnto constitutional act of culturalarcheology,of the recupera- racy, his "Historia secreta de los tion of a historicalrecord. But it is impor- homosexuales portefios," a series of notes tant to underscore that the materials he for a one-hundred-page essay, now titled analyzesare not simplyforgottenhistorical "Historiasecreta de los homosexuales en documents.That they may be in the main, Buenos Aires,"includedin his 1997collecas dust-ridden physical objects and as un- tion, Escritossobreescritos,ciudadesbajo read texts. Nevertheless, the underlying ciudades.LikeSalessi, Sebreliis interested principlesof those documentshave contin- in recovering a "secret," or at least, a ued for over one hundredyears to enjoy a significantly Sesilenced,history.However, is more in the areaofjourveryvigorousideological life,beingnothing breli'sformation less than the very principleson which the nalism than in academic scholarship, almaster narrative of homophobiain Argen- though his preferencefor the sociological tinais grounded, both in its generalcultural is what is most evident in his work. Howmanifestationsand in its particularhigh- ever, the fact that Sebreli does not have formalacademic lightingby Per6n'spresidency(particularly Salessi's,or Perlongher's, in his second term) and by the neo-fascist training and investment in academic forregimes of the two decades beginning in malities,meansthathis essay is deficientin 1966. It is impossible to pursue a project manyways.Althoughhe covers a lot of terdevotedto discrediting andits ritoryandprovidessome intriguingbibliohomophobia embodimentswithoutunder- graphicleads, Sebrelichooses to pitch his far-reaching standingon what sociohistoricalsources it essay essentially on the anecdotal level. has been so firmly groundedandrepeatedly This choice will certainlyguaranteethat it willbe circulated andreadmorewidelythan legitimated. A note about Salessi's title: in a clever Salessi'sis likelyto be; moreover,Sebreli's rhetorical gesture, Salessi under-punctu- book was brought out by the publishing ates. Therefore,what one might expect to giant, EditorialSudamericana, which will be Midicos,maleantes andprominently disy maricas(thatis, a meanthatit is available intheland. cluster of two or three propositions) be- played invirtually everybookstore comes suggestivelyone: "medicosque son But because of his anecdotal style, maleantes y maricas."What is important Sebreli, in additionto foreclosing himself aboutthis tropingis that patriarchal ideol- fromthe sort of detailedinterpretive analyogy wouldholdthatphysiciansare one bas- sis that is necessary to grasp clearly the tion against the sociosemantic field into sociohistorical questionsat play,findshimwhichevildoersandfaggotsare subsumed. self on occasion to be coy, euphemistic, and generic in Salessi'sunder-punctuation erases this dis- withholdingof information, tinction, implying a conceptual chain in his references.Because his pointsof referwhich 1) physiciansjointhatsame sociose- ence areoftenprominent rather individuals, mantic field, 2) all three propositionsare than the archival and published texts synonymous,and 3) the field itself, itself, Salessi usuallyworks with, Sebreliis conone might postulate,a node of the overar- strained(because of the possibilityof legal by nameonly ching heterosexist patriarchy,creates all action)by the need to identify three in dialectic, rather than antagonistic, those whose personal part historyis already of the public record in some way--that is, relationship to each other. for example, the upper-crustindividuals V who were arrested and charged with corruption in 1942 in the infamous case de los cadetes del There is perhaps no Argentine intellec- knownas the "escfindalo tual better placed to discuss homosexuality ColegioMilitar" (310),in whichyoung men

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2001 448 HISPANIA 84 SEPTEMBER

of the service academy were recruitedto serve their social betters in diverse extracurricular ways. However,in all fairness,Sebreli'sessay is not simplya repertoryof intriguinggossip of the "Oh,he was, was he?"sort. Rathhis chronicleof homoer, he contextualizes sexual highlightswith a discussionof pamphlets, edicts, novels, and other printed items to create an extensive mosaic in the construction of a synecdochal account of the pursuitof allformsof homoeroticdesire thatone wouldhave expected to have been America's presentin one of Latin majorand most prosperous cities,andtherefore,most diverse metropolitan concentrations. In terms of the uncovering of a "secret hiswhatSebrelihas to offeris a countertory," text to the sinisterlyeffective silencing of the details of actual lives that has been a of consequenceof the structures prominent homophobia. Sebreli's essay does not occur in a vacuumsince he has since the beginningof his intellectualcareer touched in various ways on aspects of homoeroticism.I analyze elsewhere Sebreli's interest in his youth in Evita Per6n, whom he saw as a figure of authenticmilitancy(authenticin the Sartrean sense), in his essay Eva Perdn, javentura o militante? (orig. 1966). Although Sebreli subsequently renounced such an interpretation in Los deseos imaginariosdel peronismo(1983),it is still profitable to read the 1966 book for the rhetoric with which Sebreli characterizes EvitaPer6n, one that is markedby the utilizationof campy soap opera motifs. Evita Per6n went on, of course, to be a lesbigay icon in the 1970s and 1980s with the Montonerosrefrain,"SiEvitaviviera,seria montonero" seria tropedas "SiEvitaviviera, tortillera." Subsequently,in Fzitbolymasas

(1981), Sebreli touches on the erotic dimensions of forms of homosocial popular culture like soccer (the title of Sebreli's book is surely a trope on Freud's Psychologyof the Masses, in which the latter alleges that every masculine society is libidinally homosexual). As the author of the most widely reprinted text in the area of Argentine so-

cial analysis,BuenosAires;vidacotidiana y alienacidn (1964), Sebreli has enormous intellectualand culturalcredibility.Thus, limitations of "Histowhatever the academic ria secreta"maybe, it is likelyto have wide distribution and exercise considerable forthe dual influencein a climatepropitious projectof denouncinghomophobiaand legitimatingand makingvisible homoerotic life and culture. VI I do not wish to close this discussion withoutreferenceto feministcontributions to the discussion of homoeroticismin contemporary Argentina.But, in keeping with the principleof differencewith respect to women'slives, I do notwantsimplyto comment on distaffequivalentsof Perlongher, Salessi, and Sebreli, although one might well refer to the monumentalpresence of AlejandraPizarnikand to scholarship in Argentinaabouther texts by women interested in gender issues, such as Monz6n. However,far more interesting,it seems to me, wouldbe to refer to two other dimensions of culturalproductionthat can, with as partof the be regarded some indulgence, activitiesof intellectuals. The first is the filmmaking of Maria LuisaBemberg (1922-95). Bemberg only made six feature-length films, and she did not begin her majorwork until she was in her lateforties.Yet,Bembergis nowrecogwoman nized as one of the most important of LatinAmerica,andcertainly filmmakers the most famous from Argentina. Moreover, most of her films are, in one way or La seniora de nadie another,queer-marked: the of a Nora-like tells upperstory (1982)3 middle-classwomanwho walks out on her familyand eventuallyends up livingwith a gay man.The filmcloses, afterhe has been gay-bashed, with the two cuddling each

other protectively in the same bed. Camila (1985), on the historical figure of Camila O'Gorman, who seduced a priest and attempted to make a new life with him, was executed in part with the urgings of her father, along with her lover, despite the fact

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTELLECTUALS AND HOMOEROTICISM 449

that she was pregnant. What is queer- should be noted that the full authorstatemarkedaboutthis film is the way in which ment reads: Ilse Fuskova en dialogo con the bodyof Imanol Marek.This is imArias,the priest,is made SilviaSchmid.Claudina into an objectof the femalegaze and,there- portantbecause the book is composedof a fore, of the spectator's gaze, in a disruption long dialogue between Fuskova and of the masculinist of the Schmid,whileapproximately over-determination the lastfourth female body and the homophobicneutral- is Marek'sindependenttext. ization of male corporal sexuality. FuskovaandMarekarepartners, andthe Bemberg'sfourthfilm, Yola peor de todas selection of photographsincludesmaterial of their union (1990), although stated to be based on relatingto the officialization OctavioPaz'sbiographyof the seventeenth in the Iglesia de la Comunidad MetroSor politana inJune 1992.As a couplethey have centuryMexicanwriterandintellectual, in numerous lesbianeventsand Juana In6s de la Cruz, Sor Juana o las participated de lafe, provides,at severalcrucial programs inArgentina, in the UnitedStates, trampas junctions,openingstowardalleged lesbian and in various countries in Europe, and details of Sor Juana'slife that are neither theirbook is unquestionably the best statelegitimatedby Paz's biographynor in any ment of OutandProudthathas come from where there has been considerway by the existing documentaryrecord, Argentina, despite the way in which many see Sor able struggle with frustratingsetbacks in Juana as a Mexican lesbian foremother. getting a lesbian andgay movementgoing Sor since the return to constitutionaldemocMoreover, Bemberg also "enhances" Juana's disobedience,andthereis a terrible racy in the mid-1980s. This bookmakesclearthatFuskovaand didher ironyin the factthatshe apparently research on the film priorto publication of Marek are committedto the international Their very recentresearchthatwouldessentially movementof homoeroticliberation. rewritethe ending of her film and, in fact, interest in analyzingthe patternsof resisconfirmSorJuana's successfulinsubordina- tance to such a movementis limitedto pattion vis-a-visecclesiastical authorities.Fi- terns of homophobia in Argentina as partof lastfilm,De esonose habla a wayof understanding homoeroticism that nally,Bemberg's (1993), starring Marcelo Mastroiani,is a may not fit comfortablyinto the internapaean to human difference, narrated by tional movement (i.e., homoeroticism in mostnotable with Alfredo Alc6n,Argentina's gay LatinAmericamayresist a correlation star of film and stage, in which dwarfism identitypolitics). Clearly,the authorsand and the refusaleven to recognize its exist- the movementthey representderivefrom ence constitute a metaphorthat is easily the internationalist climatein contemporary the best wayeffectively interpretedfrom a queer perspective.The Argentina, currently factthatthecentral character runsoffwiththe to promotea gay and lesbian agenda. Fuskova's and Marek's separate docucircus, a legendary option for queers and otherradically different ments individuals, depict lesbian coming-of-agein Arprovides an additional resonanceto the film. gentine society. They discuss their immigrant backgrounds,focus on their respecVII tive marriagesand motherhoods, and reveal that both enjoy good relations with To the best of my knowledge, the only their children and former husbands. The scholarly study on lesbianism in a Latin Fuskovaand Schmid dialogue is very solAmerican society is Luiz Mott's O les- idly structured: it is apparent that they bianismo no Brasil (1987).4Fuskova and agreed beforehandon essential points to Marek's documentary appears to be the cover. firstbook-length Besides exploringcrucialpoints of lesworkrelatingto Argentina and the first work in which women them- bian identityand its constructionas a refuselves recount their own experiences. It tationof the patriarchy,they explorelesbi-

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

450 HISPANIA 84 SEPTEMBER 2001

anism in the context of LatinAmericanand Argentina.They do not attenuatethe ways in whichlesbianismforthrightly challenges the patriarchy-no euphemisms, no compromisewith the squeamishness and the defensive smugness of so much of the Publication mediain Argentina. by Planeta, one of the majorpublishinghouses in Arconsorgentinaandpartof an international tium, lends the book all of the legitimacy thatcomes frombeing and mainstreaming widely distributed and prominently displayed. Inclusion of the book is appropriate in the present discussion. In additionto the considerable press and TV coverage of FuskovaandMarekfortheirbook andtheir political activism, Fuskova is a published poet. Various sections of Luna de vereda (1986with Nelda Guix6)andBailadorade suefios(1988with SabinaBertz), are reproduced in the book. The visibilitythis book has providedfor lesbianism in Argentina (enhancing a broad range of activitiesby severaldozenlesbianactivistorganizations in Buenos Aires since the returnto constitutional democracy),andthe feministspace providedby institutionslike the Casade la intellectual diLuna,constitutean important mension,in a key markedby women'shisrecordof homoerotic tory,forthe significant interestsin latetwentieth-century Argentina.

0

WORKS CITED

NOTES

1Forspecificresearchopinionon these texts, see the entriesin LatinAmericanWriters on GayandLesbian Themes.See also essays by Fosterin Contemporary Argentine Cinema (Ortiz de ZArate),Sexual Textualities;Essays on Queer/ing Latin American Dawi;Alejandra Writing (Enrique Pizarnik),Violence in ArgentineLiterature(Pizarnik),Gayand Lesbian Issues in Latin American Writing (Manuel Puig; and"Consideraciones en tornoal Pizarnik), Alejandra homoerotismoen el teatroargentino." 2The followingcharacterization is based uponmy entryon Argentinain TheEncyclopedia ofHomosexuality. 3 Setiorade nadie was Bemberg'ssecond film; I have not had access to Momentos (1980). 4 Commentshere are based in parton my forthcomingbookon BuenosAiresandurbancultural production (University Press of Florida).

Foster, David William.Gayand LesbianThemesin Latin American Writing.Austin: U of Texas P, 1991. and the Castillo'sLos invertidos -. "JoseGonzAlez LatinAmeriVampire Theoryof Homosexuality." can TheatreReview22.2 (1989): 19-29. Also includedin GayandLesbianThemes. . Producci6n cultural e identidadeshomoer6ticas: de la UniSanJose: Editorial y aplicaciones. teoria versidadde CostaRica,2000. -. Sexual Textualities:Essayson Queer/ing Latin AmericanWriting. Austin:U of Texas P, 1997. in Argentine Literature: Cultural -. Violence Responses to Tyranny. U of MissouriP, 1995. Columbia: Marek. Amorde mujeres: Fuskova,Ilse, andClaudina el lesbianismo en la Argentina, hoy.BuenosAires: Planeta,1994. "Sexualidad, Geirola,Gustavo. y teatralidad anarquia en Los invertidosde GonzAlezCastillo."Latin AmericanTheatre Review28.2 (1995):73-84. BuenosAires: GonzAlez Jose. Losinvertidos. Castillo, PuntosurEditores,1991. LatinAmericanWriters on Gayand LesbianThemes; A Bio-Critical Ed. DavidWilliamFosSourcebook. ter. Westport,CT:GreenwoodPress, 1994. al mito de la acercamiento Monz6n,Isabel.Bdthory: CondesaSangrienta. Buenos Aires: Feminaria Editora,1994. Parker,RichardG. Bodies,pleasures,and passions: Brazil. Boston: sexual culture in Contemporary Beacon,1991. Perlongher,N6stor.O neg6ciodo mich,;prostituifdo viril em Sdo Paulo. Sdo Paulo:Brasiliense,1987. masculina.BuenosAires: Also as La prostituci6n Edicionesde la Urraca,1993. -. Prosaplebeya; ensayos1980-1992. BuenosAires: EdicionesColihue,1997. Salessi,Jorge.Midicosmaleantes y maricas; higiene, en la construcci6n criminologia y homosexualidad de la naci6n argentina. (Buenos Aires: 18711914). Rosario,Arg.: Beatriz Viterbo Editora, 1995. Sebreli, Juan Jos6. Buenos Aires; vida cotidiana y alienaci6n.151ed. BuenosAires:EdicionesSiglo Veinte, 1979.Orig.1964. 4aed. Buenos delperonismo. -. Losdeseos imaginarios Aires:Editorial Legasa,1984.Orig.1983. -. Eva Per6n, gaventurao militante?4a ed. ampl. BuenosAires:Editorial LaPleyade,1971. -. Fitbol y masas.Buenos Aires:EditorialGalerna, rev. ed. as La era delFatbol. 1981[?]Substantially BuenosAires:Editorial 1998. Sudamericana, -. "Historia secretade los homosexualesen Buenos Aires." Escritos sobre escritos, ciudades bajo ciudades.Buenos Aires:EditorialSudamericana, 1997.275-370. -. "Historia secretade los homosexualesportefios." Perfil27 (1983):6-13.

This content downloaded from 157.193.48.161 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 08:06:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Вам также может понравиться

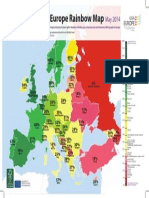

- Side B - Rainbow Europe Index May 2014Документ1 страницаSide B - Rainbow Europe Index May 2014Patricio PérezОценок пока нет

- Side A - Rainbow Europe Map May 2014Документ1 страницаSide A - Rainbow Europe Map May 2014Patricio PérezОценок пока нет

- The Wounded Body of Proletarian Homosexuality in Pedro Lemebel's Loco Afán - Palaversich, Diana & Allatson, PaulДокумент21 страницаThe Wounded Body of Proletarian Homosexuality in Pedro Lemebel's Loco Afán - Palaversich, Diana & Allatson, PaulPatricio PérezОценок пока нет

- 3 DDuckДокумент6 страниц3 DDucksr_mahapatraОценок пока нет

- Pountain 2003 - 9.2. Vestigial Spanish VarietiesДокумент24 страницыPountain 2003 - 9.2. Vestigial Spanish VarietiesPatricio PérezОценок пока нет

- Polish RecipesДокумент20 страницPolish RecipesPatricio Pérez100% (2)

- Miranda's Paradox Essay OefeningenДокумент5 страницMiranda's Paradox Essay OefeningenPatricio PérezОценок пока нет

- The Damnation of FaustusДокумент12 страницThe Damnation of FaustusPatricio PérezОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (120)

- Critique On The Lens of Kantian Ethics, Economic Justice and Economic Inequality With Regards To Corruption: How The Rich Get Richer and Poor Get PoorerДокумент15 страницCritique On The Lens of Kantian Ethics, Economic Justice and Economic Inequality With Regards To Corruption: How The Rich Get Richer and Poor Get PoorerJewel Patricia MoaОценок пока нет

- AssignmentДокумент25 страницAssignmentPrashan Shaalin FernandoОценок пока нет

- The Difference Between The Bible and The Qur'an - Gary MillerДокумент6 страницThe Difference Between The Bible and The Qur'an - Gary Millersearch_truth100% (1)

- Financial Management: Usaid Bin Arshad BBA 182023Документ10 страницFinancial Management: Usaid Bin Arshad BBA 182023Usaid SiddiqueОценок пока нет

- BB Winning Turbulence Lessons Gaining Groud TimesДокумент4 страницыBB Winning Turbulence Lessons Gaining Groud TimesGustavo MicheliniОценок пока нет

- Working Capital FinancingДокумент80 страницWorking Capital FinancingArjun John100% (1)

- SUDAN A Country StudyДокумент483 страницыSUDAN A Country StudyAlicia Torija López Carmona Verea100% (1)

- Frias Vs Atty. LozadaДокумент47 страницFrias Vs Atty. Lozadamedalin1575Оценок пока нет

- Swami VivekanandaДокумент20 страницSwami VivekanandaRitusharma75Оценок пока нет

- The State of Iowa Resists Anna Richter Motion To Expunge Search Warrant and Review Evidence in ChambersДокумент259 страницThe State of Iowa Resists Anna Richter Motion To Expunge Search Warrant and Review Evidence in ChambersthesacnewsОценок пока нет

- HP Compaq Presario c700 - Compal La-4031 Jbl81 - Rev 1.0 - ZouaveДокумент42 страницыHP Compaq Presario c700 - Compal La-4031 Jbl81 - Rev 1.0 - ZouaveYonny MunozОценок пока нет

- Philippine CuisineДокумент1 страницаPhilippine CuisineEvanFerrerОценок пока нет

- Hilti 2016 Company-Report ENДокумент72 страницыHilti 2016 Company-Report ENAde KurniawanОценок пока нет

- SOL 051 Requirements For Pilot Transfer Arrangements - Rev.1 PDFДокумент23 страницыSOL 051 Requirements For Pilot Transfer Arrangements - Rev.1 PDFVembu RajОценок пока нет

- Rainiere Antonio de La Cruz Brito, A060 135 193 (BIA Nov. 26, 2013)Документ6 страницRainiere Antonio de La Cruz Brito, A060 135 193 (BIA Nov. 26, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCОценок пока нет

- Anderson v. Eighth Judicial District Court - OpinionДокумент8 страницAnderson v. Eighth Judicial District Court - OpinioniX i0Оценок пока нет

- Basic Fortigate Firewall Configuration: Content at A GlanceДокумент17 страницBasic Fortigate Firewall Configuration: Content at A GlanceDenisa PriftiОценок пока нет

- Tanishq Jewellery ProjectДокумент42 страницыTanishq Jewellery ProjectEmily BuchananОценок пока нет

- Mental Health EssayДокумент4 страницыMental Health Essayapi-608901660Оценок пока нет

- Gerson Lehrman GroupДокумент1 страницаGerson Lehrman GroupEla ElaОценок пока нет

- Assets Misappropriation in The Malaysian Public AnДокумент5 страницAssets Misappropriation in The Malaysian Public AnRamadona SimbolonОценок пока нет

- Sculi EMT enДокумент1 страницаSculi EMT enAndrei Bleoju100% (1)

- EZ 220 Songbook Web PDFДокумент152 страницыEZ 220 Songbook Web PDFOscar SpiritОценок пока нет

- StarbucksДокумент19 страницStarbucksPraveen KumarОценок пока нет

- Price ReferenceДокумент2 страницыPrice Referencemay ann rodriguezОценок пока нет

- Supermarkets - UK - November 2015 - Executive SummaryДокумент8 страницSupermarkets - UK - November 2015 - Executive Summarymaxime78540Оценок пока нет

- 1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsДокумент3 страницы1.1 Cce To Proof of Cash Discussion ProblemsGiyah UsiОценок пока нет

- Ashish TPR AssignmentДокумент12 страницAshish TPR Assignmentpriyesh20087913Оценок пока нет

- Digi Bill 13513651340.010360825015067633Документ7 страницDigi Bill 13513651340.010360825015067633DAVENDRAN A/L KALIAPPAN MoeОценок пока нет

- Estimating Guideline: A) Clearing & GrubbingДокумент23 страницыEstimating Guideline: A) Clearing & GrubbingFreedom Love NabalОценок пока нет