Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Nevada Lawyer: Making Sense of Nevada's Alter Ego Doctrine

Загружено:

JossherАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Nevada Lawyer: Making Sense of Nevada's Alter Ego Doctrine

Загружено:

JossherАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

MAKING SENSE OF NEVADAS ALTER EGO DOCTRINE

BY WILLIAM H. STODDARD, JR. ESQ.

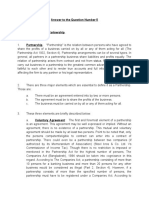

In 1957, the Nevada Supreme Court established the alter ego analysis still used by Nevada courts today (now codified by statute) to determine whether or not to pierce through a corporate veil to find a shareholder, officer, director or affiliated corporation liable for the acts of a corporate defendant. Frank McCleary Cattle Co. v. Sewell, 73 Nev. 279, 282, 317 P .2d 957, 959 (1957), reversed on other grounds in Callie v. Bowling, 123 Nev. 181, 160 P .3d 878 (2007). As set forth in the statutory version at NRS 78.747(2):

A stockholder, director or officer acts as the alter ego of a corporation if: a. The corporation is influenced and governed by the stockholder, director or officer; b. There is such unity of interest and ownership that the corporation and the stockholder, director or officer are inseparable from each other; and c. Adherence to the corporate fiction of a separate entity would sanction fraud or promote a manifest injustice.1

Among the lessons of the many Nevada Supreme Court cases that have followed McCleary Cattle Co. is the particular importance to the court of the third factor listed above avoiding fraud or manifest injustice. Many of the courts decisions and respected commentators have observed that, while there may be a number of facts in a particular case tending to favor a finding of alter ego under the first two of the factors of NRS 78.747(2), unless there are also facts tying those factors to a fraud or injustice upon the plaintiff, the court is not likely to pierce the corporate veil for the plaintiffs benefit. It should not be surprising that in a state that prides itself on a protective corporate environment, the court has repeatedly emphasized that the corporate cloak is not lightly thrown aside; however, the court will disregard that cloak if adherence to the fiction of a separate entity ... [would] sanction a fraud or promote injustice. Baer v. Walker, 85 Nev. 219, 452 P.2d 916 (1969); North Arlington Medical Bldg., Inc. v. Sanchez, 86 Nev. 515, 520, 471 P.2d, 240, 243 (1970).

Nevada Lawyer

December 2012

Factors 1 and 2: Substantial Influence and Unity of Interest and Ownership

Several Nevada Supreme Court cases have been quick to find that the first two alter ego factors are met, particularly in small, closely held corporations involving a single or small group of stockholders, directors or officers. See e.g., Caple v. Raynel Campers, Inc., 90 Nev. 341, 343, 526 P.2d 334, 336 (1974, abrogated on other grounds in Ace Truck and Equip. Rentals v. Kahn, 103 Nev. 503, 746 P.2d 132). Indeed, most of the cases decided since McCleary Cattle Co. have involved small, closely held corporations. In such cases, the requisite influence over the corporation between small groups of shareholders and other actors is typical, though, importantly, the court has noted some exceptions. For example, in Lipshie v. Tracy Inv. Co., 93 Nev. 370, 377, 566 P.2d 819, 823 (1977) the court held that the mere fact of a parent owning all of the stock of a subsidiary corporation, with identical officers, without more, was insufficient to show the requisite influence in governance to meet the first factor. Rather, the court has held that it must be shown that the subsidiary corporation is so organized and controlled, and its affairs are so conducted that it is in fact a mere instrumentality or adjunct of another corporation. Bonanza Hotel Gift Shop, Inc. v. Bonanza No. 2, 95 Nev. 463, 466, 596 P.2d 227, 229 (1979). See also, Wyatt v. Bowers, 109 Nev. 593, 596-597, 747 P.2d 881, 883 (1987); Truck Ins. v. Palmer J. Swanson, Inc., 124 Nev. 629, 636, 189 P.3d 656, 660-661 (2008). With regard to the question of whether there is such a unity of interest and ownership that the corporation, and the person sought to be held liable, are virtually inseparable, the court has enunciated a number of familiar factors, including by way of common examples: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Comingling of funds; Undercapitalization; Unauthorized diversion of funds; Failure to observe corporate formalities; The existence (or non-existence) of separate bank accounts; 6. Whether sister corporations had independent headquarters; 7. Whether separate corporations had separate business responsibilities and operations; and 8. Whether dividends were paid to shareholders.

circumstances of each case. Polaris Indus. Corp. v. Kaplan, 103 Nev. 598, 601, 747 P.2d 884, 887 (1987) (Citations omitted). The real question, then, is how the court generally decides when the existence of some of the factors described above favor the imposition of alter ego liability.

Factor 3: Avoiding Fraud or Injustice

As pointed out in In re James Giampietro, 317, B.R. 841, 853 (Bankr. D. Nev. 2004), Bankruptcy Judge Bruce A. Markell, while conducting an extensive review of Nevadas case law in this area, and relying in part upon a decision from 20 years prior by U.S. District Court Judge Lloyd D. George (then serving as a bankruptcy judge), observed that the prevention of fraud or manifest injustice is the most meaningful of the NRS 78.747 factors. It is not enough simply that some of the factors favoring alter ego liability exist. More importantly, based on the courts prior holdings in this area, there must be a causal connection between those factors and the plaintiffs injury. Quoting Georges earlier analysis in In re Twin Lakes Village, Inc., 2 B.R. 532, 542 (Bankr. D. Nev. 1980), Judge Markell noted the element of reliance, or more particularly, on reasonable reliance by the complaining creditor upon debtor conduct which would indicate either the absence of a corporate form or the assumption of liability by a person or entity controlling an openly visible corporation, has been the primary focus of Nevada courts. This conclusion, requiring a causal connection between the alter ego factors and actual harm to the plaintiff has been discussed in various Nevada Supreme Court cases. In North Arlington Medical Building, Inc., v Sanchez Construction Co., 86 Nev. 515, 471 P.2d, 240 (1970), where a corporate president, who had completely influenced and managed the corporation failed to follow corporate formalities and left the corporation undercapitalized, the court nevertheless held that the plaintiff failed to show any causal connection between the way the corporation was capitalized and its subsequent inability to pay the obligation owed. As a result, the court found that there was no evidence showing how those factors sanctioned a fraud or promoted an injustice toward the plaintiff. This holding suggests that in order to utilize undercapitalization as grounds for piercing the veil, it will likely need to be shown to have existed at the time the debts were incurred. See also, Paul Steelman, Ltd. v. Omni Realty Partners, 110 Nev. 1223, 884 P.2d 549 (1994). Similarly, in Lipshie v. Tracy Inv. Co., 93 Nev. 370, 377, 566 P.2d 819, 823 (1977), while finding that a parent and subsidiary corporation had identical officers and shareholders, and that the corporation was undercapitalized at the time of trial, the court observed that it is not reasonable to conclude that the [parent corporation] undercapitalized [the subsidiary corporation] in order to frustrate the payment of its obligation to plaintiff. While other factors supported a finding of alter ego liability, there was no causal connection between those factors and the injury suffered by plaintiff, such that the third factor was not met.

See e.g., Polaris Indus. Corp. v. Kaplan, 103 Nev. 598, 601, 747 P.2d 884, 887 (1987); Mosa v. Wilson-Bates Furniture Co., 94 Nev. 521, 522, 583 P.2d 453, 454 (1978); Bonanza Hotel Gift Shop, Inc. v. Bonanza No. 2, 95 Nev. 463, 467, 596 P.2d 227, 230 (1979); Rowland v. Lepire, 99 Nev. 308, 317-318, 662 P.2d 1332, 1338 (1983); Truck Ins. Exchange v. Palmer J. Swanson, Inc., 124 Nev. 629, 636, 189 P.3d 656, 661 (2008). While the court will often find the presence of at least some of the foregoing factors favoring the application of alter ego liability, the court has also held that there is no litmus test for determining whether the corporate veil should be disregarded; rather, the result depends upon the

continued on page 8

December 2012

Nevada Lawyer

MAKING SENSE OF NEVADAS ALTER EGO DOCTRINE

Conversely, in a case nding the requisite causal connection, Mosa v. Wilson-Bates Furniture Co., 94 Nev. 521, 522, 583 P.2d, 453(1978), the court found that it was appropriate to pierce the corporate veil where the shareholder had given personal assurances at various times that he would personally pay the outstanding debts of [the corporation], and that such assurances were given to induce forbearance by [plaintiff] in asserting its claim against the corporation for debts due and owing.

continued from page 7

Conclusion

It is vital for corporations to rigorously observe formalities and to take action that will avoid the applicability of alter ego liability. Nevertheless, in the litigation context, where an effort is made to actually pierce the corporate veil, it appears that the Nevada Supreme Courts primary focus is on whether there is any causal connection between an exertion of undue inuence over an entity by a dominant shareholder, or the failure to observe corporate formalities, or keep the corporation sufciently capitalized, etc., and the ultimate harm caused to the plaintiff.

1 An important question is whether the methods for piercing a corporate veil apply equally to piercing Nevada limited liability companies. In In re James Giampietro, 317 B.R. 841, 846 (D. Nev. 2004) the bankruptcy court asserted it is highly likely the Nevada courts would extend the alter ego doctrine to members of limited liability companies. This view appears to have been, at least to some extent, conrmed by Scott J. Webb v. Schull, et al., 128 Nev. Adv. Op. 8, at page 11, (March 2012) in which the Nevada Supreme Court analyzed the alter ego arguments at issue therein under the standard set forth in NRS 78.747, even though that case involved a limited liability company. It should however be noted that, at footnote 3 to the Schull decision, the court indicated it was doing so based on the assumption of both parties that the statute would apply, and was not necessarily specically ruling on that question, as it would need to do if the issue were disputed.

WILLIAM H. STODDARD, JR. is a partner at Albright, Stoddard, Warnick & Albright. He represents clients in various fields in corporate and real estate transactions, as well as litigation matters.

knowledge from nationally-acclaimed experts on topics that are relevant to your practice while fullling your annual CLE

Register now at or call (800) 285-2221

8 Nevada Lawyer December 2012

Вам также может понравиться

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Tips For Effective Punctuation in Legal WritingДокумент12 страницTips For Effective Punctuation in Legal WritingJossherОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Essentials of A Position PaperДокумент1 страницаEssentials of A Position Paperricky nebatenОценок пока нет

- Philippine Legal Citation Guide PDFДокумент17 страницPhilippine Legal Citation Guide PDFMasterboleroОценок пока нет

- Carnelli v. Eighth Judicial DistrictДокумент15 страницCarnelli v. Eighth Judicial DistrictJossherОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Back From The Dead-Suing Dissolved Corporations in CaliforniaДокумент2 страницыBack From The Dead-Suing Dissolved Corporations in CaliforniaJossherОценок пока нет

- Red Notes: TaxДокумент41 страницаRed Notes: Taxjojitus100% (2)

- Red Notes: TaxДокумент41 страницаRed Notes: Taxjojitus100% (2)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Nevada Prejudgment InterestДокумент57 страницNevada Prejudgment InterestJossherОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Prime Interest Rate in The State of NevadaДокумент2 страницыPrime Interest Rate in The State of NevadaJossherОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Partnership PDFДокумент7 страницPartnership PDFAhn JelloОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Corporation Law WA 1Документ10 страницCorporation Law WA 1Roma Dela Cruz0% (1)

- 05. Đề Thi FM1 Cho 11 CLC Thi Đợt 1 HK2 NH 2021.2022Документ5 страниц05. Đề Thi FM1 Cho 11 CLC Thi Đợt 1 HK2 NH 2021.2022Hiển HoàngОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Gen Provision RCCPДокумент12 страницGen Provision RCCPkathlene depalcoОценок пока нет

- Corpo NotesДокумент7 страницCorpo NotesKarlОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- PART 2 bl07Документ12 страницPART 2 bl07Reggie Alis100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Texas LLC Update 0509141033Документ43 страницыTexas LLC Update 0509141033tortdogОценок пока нет

- Organization of Agribusiness Firms: Mubashir Mehdi, Adnan Adeel and Burhan AhmadДокумент20 страницOrganization of Agribusiness Firms: Mubashir Mehdi, Adnan Adeel and Burhan AhmadhusnainОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Organizing & Financing A New Venture: Book: Leach, J. C., & Melicher, R. W. (2011) - Entrepreneurial FinanceДокумент38 страницOrganizing & Financing A New Venture: Book: Leach, J. C., & Melicher, R. W. (2011) - Entrepreneurial FinanceShafqat RabbaniОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Nirma LTDДокумент44 страницыNirma LTDabhayjadaunsОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- War22e Ch13Документ77 страницWar22e Ch13tamparddОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Master Delinquent Taxes 10 CountiesДокумент219 страницMaster Delinquent Taxes 10 CountiesAlyssa RobertsОценок пока нет

- Liquidator+ Powers and DutyДокумент19 страницLiquidator+ Powers and DutyHarleen CaurОценок пока нет

- What Public Limited Company (PLC) Means in The U.K.: Investing Simulator Economy Personal Finance News Reviews AcademyДокумент11 страницWhat Public Limited Company (PLC) Means in The U.K.: Investing Simulator Economy Personal Finance News Reviews AcademyTrisha SambranoОценок пока нет

- Annual Return: Form No. Mgt-7Документ19 страницAnnual Return: Form No. Mgt-7Vipul DhokteОценок пока нет

- Answer To The Question Number 5Документ4 страницыAnswer To The Question Number 5Md. Yasir ArafatОценок пока нет

- Aging 5.31.2021Документ171 страницаAging 5.31.2021Ricardo DelacruzОценок пока нет

- PartnershipДокумент4 страницыPartnershipkrish masterjeeОценок пока нет

- Offshore Marintec Russia 2014 Exhibitor ListДокумент12 страницOffshore Marintec Russia 2014 Exhibitor ListKen EdwardОценок пока нет

- Corporation Reviewer 2 1Документ166 страницCorporation Reviewer 2 1hizelaryaОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Chapter 12Документ42 страницыChapter 12Ivo_Nicht100% (4)

- LLP Presentation by ROCДокумент18 страницLLP Presentation by ROCKalyanKumarОценок пока нет

- Unit 1: Introduction To Company AccountsДокумент16 страницUnit 1: Introduction To Company AccountspoojaОценок пока нет

- CS Executive Company Law Revision NotesДокумент84 страницыCS Executive Company Law Revision NotesNaman Jain100% (1)

- Lesson 4 Forms of Business OrganizationsДокумент4 страницыLesson 4 Forms of Business OrganizationsANDREA LAREGOОценок пока нет

- Venture Capitalists of IndiaДокумент17 страницVenture Capitalists of IndiaShaantanu GaurОценок пока нет

- Saudi ArabiaДокумент5 страницSaudi Arabia1mohammadОценок пока нет

- LEsdsДокумент115 страницLEsdsJosé TelloОценок пока нет

- Salomon V Salomon Case'Документ6 страницSalomon V Salomon Case'All Agreed CampaignОценок пока нет

- SY 2018-2019 501 - Corporation - GAVIOLA: Articles - Articles of IncorporationДокумент46 страницSY 2018-2019 501 - Corporation - GAVIOLA: Articles - Articles of IncorporationSammy EscañoОценок пока нет