Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Digital Compositing: A Brief Primer

Загружено:

krshawОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Digital Compositing: A Brief Primer

Загружено:

krshawАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Digital Compositing A brief primer by K.

Shaw Have you ever wondered how Nicolas Cage can ride a motorcycle without holding on to the handlebars? Maybe you've heard terms like "blue screen", "green screen", or "chroma-key". The weather man's tie sometimes turns invisible. How does that happen? Once upon a time, in an age before computers, the special effects wizards at Hol lywood film studios would put multiple strips of film through a photochemical pr ocess called "compositing". If you had film of an actor standing in front of a d ark blue backdrop, certain processes could be used to make background film show through the dark blue parts of the foreground film. Using special projection tec hniques, you could even "matte" the foreground layer over a limited portion of t he background layer to make it appear that the action was filmed from far away. In the computer era, these primitive techniques have been replaced with cheaper, easier, and more convincing alternatives. Most newcomers to digital compositing will refer to it with such terms as "layer ing" or "green screening". Such individuals typically assume that computer softw are is sufficient to automatically create the convincing illusion that we know a nd love. It is not. Simply layering a green screen clip over a background clip i n a non-linear video editor will result in jagged or blurry outlines that break the illusion. Such flaws (called "artifacts") took other forms in the days of an alog film compositing. For example, in Ben-Hur (1959), dark blue outlines are cl early visible on actors in the sailing shots. In Star Wars (1977), the TIE fight ers are surrounded by sharp-edged auras when composited over a black space backg round. In Terminator 3 (2003), Arnold drives a truck in front of a green screen without any visual artifacts whatsoever. This incredible improvement is only pos sible thanks to the careful use of sophisticated digital compositing software. A team of effects artists oversaw the compositing shots of each of these films, a nd each film pushed compositing to the technological limits of its time. For the casual film maker who wishes to explore digital compositing, non-linear editing software such as Adobe Premiere or Sony Vegas is recommended. For those who are not satisfied with the sub-standard compositing of those programs, the a uthor recommends using more advanced node-based compositing software such as Ble nder. Blender is free software, but that freedom comes at a price. In providing the necessary low-level control to pull off a convincing compositing effect, it becomes quite difficult for a beginner to use. Perhaps the most perplexing featu re of any compositing software is varying levels of opacity. Consider the techni ques employed in a green screen effect. An actor stands in front of a sheet of b rightly colored green fabric. The camera records him or her at such an angle tha t his/her head, arms, and torso appear over the top of green. It is then the com puter's job to determine which parts are green and which are not. The actor cann ot wear a green shirt, or it will appear invisible. Common sense would indicate that any part of the image could be either "green" or "not green". However, a lo t of compositing software is capable of recognizing parts that are "somewhat gre en", and removing the green from those parts to make them transparent. In this w ay, one can hold a glass of water in front of a well-constructed green screen, a nd the transparency of the water will be preserved in the final image. Combined with other digital effects, this technique can result in powerful and realistic imagery that would be impractical to physically create.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Top 20 Network Administrator Interview Questions and AnswersДокумент4 страницыTop 20 Network Administrator Interview Questions and Answersmikesoni SОценок пока нет

- Radio Journalism & ProductionДокумент121 страницаRadio Journalism & ProductionShruti Pandey100% (1)

- TS 103 190 - V1.1.1 - Digital Audio Compression (AC-4) Standard PDFДокумент295 страницTS 103 190 - V1.1.1 - Digital Audio Compression (AC-4) Standard PDFHien Ly cong minhОценок пока нет

- Infrastructure For Electronic Commerce: © Prentice Hall, 2000Документ45 страницInfrastructure For Electronic Commerce: © Prentice Hall, 2000faisalaltaf68Оценок пока нет

- PRE-TEST Empowerment TechnologyДокумент40 страницPRE-TEST Empowerment TechnologyMat3xОценок пока нет

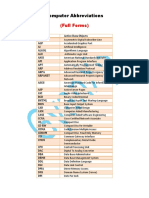

- Computer Full FormsДокумент2 страницыComputer Full FormsYogesh TiwariОценок пока нет

- DCN Question BankДокумент5 страницDCN Question Bankushapetchi18Оценок пока нет

- Computer Fundamentals - Objective Questions (MCQ) With Solutions and Explanations - Set 1Документ4 страницыComputer Fundamentals - Objective Questions (MCQ) With Solutions and Explanations - Set 1uditj06Оценок пока нет

- DVB Streamer User ManualДокумент20 страницDVB Streamer User ManualGhufranaka Aldrien NanangОценок пока нет

- Product Overview: Fax:0086-571-81110225 Tel:0086-571-81110248Документ5 страницProduct Overview: Fax:0086-571-81110225 Tel:0086-571-81110248Liviu CiobotariuОценок пока нет

- MP4 Visual Land Me-964-4gb-RedДокумент34 страницыMP4 Visual Land Me-964-4gb-Redmr_silencioОценок пока нет

- Physics DLP AllenДокумент500 страницPhysics DLP AllenSonu Ramawat100% (2)

- Maxicom Tablet PDFДокумент2 страницыMaxicom Tablet PDFOscar AcevedoОценок пока нет

- Course Module NET 102 Week 1Документ15 страницCourse Module NET 102 Week 1Royet Gesta Ycot CamayОценок пока нет

- VSX-1123-K Manual ENpdf PDFДокумент115 страницVSX-1123-K Manual ENpdf PDFJack SawyerОценок пока нет

- Graphics, Digital Media, and Multimedia: Multiple Choice: 1Документ15 страницGraphics, Digital Media, and Multimedia: Multiple Choice: 1Wika Maulany FatimahОценок пока нет

- 2873 Manual 1 U1980Документ35 страниц2873 Manual 1 U1980SarzaminKhanОценок пока нет

- Image Runner 1025 PDFДокумент6 страницImage Runner 1025 PDFRafael A. Tizol HdezОценок пока нет

- FOLIO T4 IctДокумент9 страницFOLIO T4 IctMizTa YaVin ZFОценок пока нет

- Release Note Fml-8Mod: K56flex Modem Function ModuleДокумент18 страницRelease Note Fml-8Mod: K56flex Modem Function Moduleniko67Оценок пока нет

- CP80 Hardware Manual PDFДокумент151 страницаCP80 Hardware Manual PDFjeremyОценок пока нет

- Analog and Digital Communications - H. P. Hsu PDFДокумент197 страницAnalog and Digital Communications - H. P. Hsu PDFSai SamardhОценок пока нет

- LM230WF5 TLD1 PDFДокумент31 страницаLM230WF5 TLD1 PDF'RomОценок пока нет

- Research On ASPECT RATIOДокумент5 страницResearch On ASPECT RATIOPrince Aphotinel OnagwaОценок пока нет

- Cisco Collaboration Solutions For Partner EngineersДокумент197 страницCisco Collaboration Solutions For Partner EngineersSliceanchorОценок пока нет

- CCN MCQДокумент2 страницыCCN MCQAtharvОценок пока нет

- Computer Basics Packet - ReadingДокумент23 страницыComputer Basics Packet - Readingdream_nerd0% (1)

- Ah68-03026g-03 HW-N400 ZF Eng Fra Ita Por Spa 180418 PDFДокумент127 страницAh68-03026g-03 HW-N400 ZF Eng Fra Ita Por Spa 180418 PDFAlejandro CamargoОценок пока нет

- NPort 5100 Series Users Manual v4 PDFДокумент104 страницыNPort 5100 Series Users Manual v4 PDFSven SeidelОценок пока нет

- DS-2DF8236IX-AEL (W) (B) 2MP 36× Network IR Speed Dome: Key FeaturesДокумент5 страницDS-2DF8236IX-AEL (W) (B) 2MP 36× Network IR Speed Dome: Key FeaturesrahulshazОценок пока нет