Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Chu - TNF Alpha Apoptosis Review - 2013

Загружено:

Nilabh RanjanИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Chu - TNF Alpha Apoptosis Review - 2013

Загружено:

Nilabh RanjanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cancer Letters 328 (2013) 222225

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Cancer Letters

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/canlet

Mini-review

Tumor necrosis factor

Wen-Ming Chu

Cancer Biology Program, University of Hawaii Cancer Center, 651 Ilalo Street, Honolulu, HI 96813, USA

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a critical cytokine, which contributes to both physiological and pathological processes. This mini-review will briey touch the history of TNF discovery, its family members and its biological and pathological functions. Then, it will focus on new ndings on the molecular mechanisms of how TNF triggers activation of the NF-jB and AP-1 pathways, which are critical for expression of proinammatory cytokines, as well as the MLKL cascade, which is critical for the generation of ROS in response to TNF. Finally, this review will briey summarize recent advances in understanding TNFinduced cell survival, apoptosis and necrosis (also called necroptosis). Understanding new ndings and emerging concepts will impact future research on the molecular mechanisms of TNF signaling in immune disorders and cancer-related inammation. 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Article history: Received 8 June 2012 Received in revised form 4 October 2012 Accepted 12 October 2012

Keywords: TNF NF-jB/AP-1 Apoptosis/necrosis Cancer and inammation

1. Introduction Since its discovery, TNF has been the center of study for its roles in normal physiology, acute inammation, chronic inammation, autoimmune disease and cancer-related inammation. In addition, TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1)-mediated apoptosis, necrosis (also called necroptosis) and survival in TNF signaling have drawn much attention, leading to numerous new ndings and emerging new concepts. This mini-review briey summarizes the discovery and denition of TNF, its sources and its biological and pathological functions as well as the molecular mechanisms of its actions.

4. Discovery More than 100 years ago, Dr. Williams B. Coley used crude bacterial extracts to treat tumor patients. He found that the bacterial extracts had an ability to induce tumor necrosis. While tumors were regressive, patients receiving bacterial extracts also suffered from a severe systematic inammatory reaction. One of the major inammatory stimulators now known to cause this reaction was identied in 1975, when a protein factor in the serum of endotoxin-treated animals was found to cause lysis in tumor cells and was therefore named tumor necrosis factor. In 1984, the TNF gene was isolated and characterized. About the same time, another gene encoding a protein, which was puried from T lymphocytes and was named T lymphotoxin alpha (TLa) in 1968, was also isolated and characterized. These two genes were found to belong to the same family. Thus, TNF was named TNFa, while TLa was called TNFb. In 1985, Nobel Prize winner Dr. Bruce Beutler and his colleagues puried a protein called cachectin from the supernatant of endotoxin-treated macrophages. This protein induced wasting (cachexia) and septic shock in murine recipients. Cachectin and TNF were later revealed to be the same protein. 5. Sources TNFa is mainly produced by macrophages, whereas TNFb is mainly produced by T lymphocytes. Other cells can also express TNFa and TNFb at low levels. 6. Genes and proteins The human and murine TNFa genes are located on chromosome 6 and chromosome 17, respectively, and are preceded by the TNFb

2. Synonyms Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa) is also known as endotoxininduced factor in serum, cachectin, and differentiation inducing factor.

3. Denition The tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family includes TNF alpha (TNFa), TNF beta (TNFb), CD40 ligand (CD40L), Fas ligand (FasL), TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL), and LIGHT (is homologous to lymphotoxins, exhibits inducible expression, and competes with HSV glycoprotein D for HVEM, a receptor expressed by T lymphocytes), some of the most important cytokines involved in physiological processes, systematic inammation, tumor lysis, apoptosis and initiation of the acute phase reaction.

E-mail address: wchu@cc.hawaii.edu 0304-3835/$ - see front matter 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.014

W.-M. Chu / Cancer Letters 328 (2013) 222225

223

gene. Both genes are present in a single copy, are approximately 3 kilobases in size and contain 4 exons. Several DNA binding sites for the transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-jB) have been identied within the promoter region of the TNFa gene; therefore, it appears that the expression of TNFa is NF-jB dependent. A DNA binding site for the high mobility group 1 (HMG1) protein is located in the promoter region of the TNFb gene. Two forms of TNFa exist: the membrane-bound form (mTNFa) and the soluble form (sTNFa). Human mTNFa contains 157 amino acids (aa) and a 76 aa leader sequence, while mouse mTNFa contains 156 aa plus a 79 aa leader sequence. During synthesis, TNFa translocates to the cell membrane where the TNFa converting enzyme (TACE) sheds the mTNFa into sTNFa. In contrast to TNFa, TNFb only exists in the soluble form (sTNFb). TNF is conserved among species. For example, human TNF is 80% homologous to mouse TNF. The homology between TNFa and TNFb in both species is approximately 30%. 7. Biological and pathological functions TNF exerts many important physiological and pathological actions. TNF causes tumor cell necrosis (a process that involves cell swelling, organelle destruction, and nally cell lysis) and apoptosis (a process that involves cell shrinking, the formation of condensed bodies, and DNA fragmentation). Moreover, studies in TNFa- or TNFR-decient mice have revealed that TNF plays an important role in the regulation of embryo development and the sleep-wake cycle, and that TNF is important for lymph node follicle and germinal center formation as well as host defense against bacterial and viral infection. TNF has been shown to be an endogenous pyrogen that causes fever. Chronic exposure to a low dose of TNF may cause cachexia, wasting syndrome, and depression. Additionally, TNF is a key mediator of both acute and chronic systematic inammatory reactions. TNF not only induces its own secretion, but it also stimulates the production of other inammatory cytokines and chemokines. TNF is a vital player in animal models of endotoxin-induced septic shock, and in chemotherapyinduced septic shock in late-stage lung cancer patients. TNF plays a central role in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inammatory bowel diseases including Crohns disease and ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis. Finally, TNF has emerged as an important risk factor for tumorigenesis, tumor progression, invasion and metastasis. TNF is a key intermediary of cancer-associated chronic inammation. Longterm usage of aspirin decreases TNF secretion and signicantly reduces incidence of human colorectal colon cancer. Furthermore, TNF is frequently detected in biopsy samples from human breast, ovarian and renal cancers, as well as in adjacent stromal cells. It is also evident that TNF mediates the development of human malignant mesothelioma in response to environmental exposure to asbestos, and it has been shown that asbestos is not pathogenic in the absence of TNFR [1]. In other experimental murine cancer models, TNF has been shown to promote early stage liver and skin cancer, and enhance colon cancer metastases to the lung. This tumor promotion effect of TNF has also been observed in drosophila. For example, in the absence of the drosophila tumor suppressor Scribble (Scrib) gene, oncogenic protein Rasv12 can switch off the tumor suppressive activity of TNF, leading to tumor progression and invasion [2]. 8. TNF and anti-TNF therapies in autoimmune disease and cancer TNF has never been considered as a systemic anti-cancer drug because it has been implicated in a wide spectrum of systemic dis-

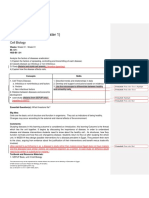

orders. However, a high dose of regional TNF not only causes necrosis and the subsequent destruction of tumor blood vessels, but also enhances efcacy of chemotherapy. Therefore, TNF has been used for regional treatment of metastatic melanoma and advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Conversely, due to the crucial role of TNF in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders and cancer-associated chronic inammation, anti-TNF treatment has been developed as a therapy for rheumatoid arthritis, inammatory bowel disease, cancer-related cachexia, leukemia and ovarian cancer. The strategies developed to block TNF signaling either utilize anti-TNF antibodies (Remicade/ Iniximab, Adalimumab/Humira and Golimumab) to neutralize sTNF, or Fc fragments of human immunoglobulin 1 fused with extracellular domains of TNFR1 or TNFR2 (Certolizumab/Cimzia and Etanercept/Enbrel) to block the interaction of TNF with TNFRs. Overall, anti-TNF therapy has been very successful in ameliorating symptoms of autoimmune disorders. However, some side effects have been reported. For example, patients receiving antiTNF regiments exhibit unexpected toxicities, and anti-TNF therapy may enhance the risk of tuberculosis infection. Most ominously, patients receiving anti-TNF therapy may have an increased risk of developing breast cancer, lung cancer, lymphoma, and skin cancer. Yet, the epidemiological review of many clinical trials involving anti-TNF therapy for RA did not nd any link between such therapy and an increased risk of cancer. Nevertheless, the potential pro-oncogenic effect of anti-TNF therapy requires further investigation. 9. Molecular mechanisms The molecular mechanisms behind TNFs actions have been extensively investigated. Particularly, scientists have been keen to elucidate how TNF triggers activation of the Ikappa B (IjB) kinase (IKK)/NF-jB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ AP-1 pathways (Fig. 1), which are essential for the expression of pro-inammatory cytokines, and to understand how TNF induces apoptosis and necrosis (Fig. 1). TNF binds to its receptors TNFR1 and TNFR2, which can either be membrane bound or soluble. TNFR1 and TNFR2 each interact with both mTNFa and sTNFa. However, TNFR1 signaling is strongly activated by both mTNFa and sTNFa, while TNFR2 signaling can only be efciently activated by mTNFa. TNFR1 is ubiquitously expressed while TNFR2 is mainly expressed on lymphocytes and endoepithelial cells. Upon ligation, either TNFR1 or TNFR2 forms a homodimer, but interestingly they do not form a TNFR1/TNFR2 heterodimer. TNFR1 contains a death domain, which allows it to interact with other death domain-containing adaptor proteins, whereas TNFR2 lacks a death domain. 9.1. Activation of the IKK/NF-jB and MAPK/AP-1 pathways When TNFR1 binds to TNF, its conformation is changed such that its death domain can interact with TNFR-associated factor containing death domains (TRADD), which in turn recruits TNFRassociated factors (TRAFs) including TRAF2 and TRAF5, as well as the cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins 1 and 2 (c-IAP1/2) to form the TNF receptor signaling complex (TNF-RSC) (Fig. 1). Not only are c-IAP1/2 important for activation of IKK, but they are also critical for activation of components along the MAPK pathway, including JNK and p38 [3]. Within the IKK pathway, a linear ubiquitin assembly complex (LUBAC) containing HOIL-1, HOIP and Sharpin has recently been identied [46]. LUBAC is recruited to the TNF-RSC by TRADD, TRAF2/5 and c-IAP1/2 (Fig. 1). Importantly, LUBAC is not only required for the stabilization of TNF-RSC, but it also adds linear ubiquitin chains to both the receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) and

224

W.-M. Chu / Cancer Letters 328 (2013) 222225

Fig. 1. A model of TNFa signaling in inammation, apoptosis and necrosis. TNF binds to TNFR1 and TNRF2. TNFR1 interacts with TRADD via its death domain (DD), in turn recruiting TRAF2, TRAF5 and c-IAP1/2 to form the TNF-RSC. RIP1 and LUBAC are then recruited to the TNF-RSC, leading to ubiquitination of RIP1 and IKKc and formation of the IKKc/IKK and TAK1/TAB1/TAB2 complexes. Polyubiquitinated RIP1 triggers TAK1 activation, which in turn activates IKKa/b, JNK and p38 leading to NF-jB and AP-1 activation, respectively. AP-1 and NF-jB bind to DNA binding sites located in the promoter regions of their target genes and initiate gene expression. TNFR1 also uses TRADD to recruit FADD and deubiquitinated RIP1. Both FADD and RIP1 use their DD to interact with DDs within the initiator pre-caspase 8, leading to its cleavage and activation. Activated caspase 8 triggers cleavage of Bid into tBid, which then enters mitochondria leading to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and subsequent cytochrome c release. Cytochrome c, together with Aparf1 and caspase 9, forms an apoptosome complex that triggers apoptosis. In addition, deubiquitinated RIP1 interacts with RIP3 forming the RIP1-RIP3 necrosome, resulting in the mutual phosphorylation of RIP1 and RIP3. RIP3 then interacts with and phosphorylates MLKL, which recruits PGAM5 (PGAM5L and PGAM5S). RIP3 phosphorylates PGAM5S, which in turn dephosphorylates Drp1 leading to its activation and subsequent necrosis. MLKL is required for the generation of ROS, which then trigger necrosis via the PGAM5/Drp1 cascade. MLKL is also important for sustained JNK activation by TNF.

the regulatory subunit of IKK, IKKc (also called NEMO), thus bringing both RIP1 and IKKc to TNF-RSC (Fig. 1). This results in the formation of the IKKc/IKKa/b complex and the TAK1 (TGFb-activated kinase 1)/TAB1/2 (TAK1 binding protein 1 and 2) complex. Intriguingly, c-IAP1/2, but not TRAF2, are E3 ligases that catalyze lysine (K) 11-, 48-, or 63-linked polyubiquitination of RIP1 and c-IAP1/2 themselves, and this ligase activity is required for the recruitment of LUBAC to c-IAP-generated ubiquitin chains [4,7]. The polyubiquitinated RIP1 triggers activation of TAK1, which in turn activates IKKa and IKKb. Although both IKKa and IKKb phosphorylate IjBa, IKKb is the major kinase leading to ubiquitination and degradation of IjBa, and subsequently leading to NF-jB translocation to the nucleus where it initiates the transcription of more than 200 NF-jB-dependent genes, including cell survival genes, pro-inammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and TNFa itself. TAK1 also activates JNK and p38, resulting in the respective phosphorylation of c-Jun and ATF2, and the subsequent formation of a c-Jun/ATF2 heterodimer called activating protein 1 (AP-1) (Fig. 1). AP-1 is another critical transcription factor and has similar functions to NF-jB. Interestingly, TNFR2 does not contain a death domain, but it is able to form a complex with TRAF2 and TRAF5, leading to the activation of NF-jB and AP-1 upon stimulation with TNF.

9.2. Induction of apoptosis TNFR1 also uses TRADD to recruit the Fas-associated proteincontaining death domain (FADD) and deubiquitinated RIP1 (Fig. 1). Both FADD and RIP1 interact with pro-caspase 8, resulting in its cleavage and activation. Activated caspase 8 in turn mediates the cleavage of the pro-apoptotic protein Bid generating a truncated form (tBid), which translocates to the mitochondria and decreases mitochondrial membrane potential resulting in cytochrome c release. Cytochrome c, together with the apoptotic protease activating factor 1 (Apaf1), binds to the initiator pro-caspase 9 forming an apoptosome complex, which activates other caspases including 3 and 7 resulting in cell apoptosis. The normal development of c-IAPs knockout mice, which show embryonic lethality, can be rescued via deletion of TNFR1 but not TNFR2, further indicating a critical role for TNFR1 in TNF-induced apoptosis [8]. 9.3. Initiation of necrosis Deubiquitinated RIP1 can also recruit the receptor-interacting protein 3 (RIP3), forming the RIP1-RIP3 necrosome. Within this necrosome, RIP1 and RIP3 phosphorylate each other, further stabilizing the complex. Moreover, the phosphorylation of RIP3 at serine

W.-M. Chu / Cancer Letters 328 (2013) 222225

225

residues 227 and 232 is essential for its interaction with and the phosphorylation of its substrate, the mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) [9,10]. Although it is currently unclear whether MLKL acts as a kinase, it is known to be a critical mediator of the interaction of the RIP1/RIP3 necrosome with the phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 (PGAM5) [11]. There are two isoforms of PGAM5, PGAM5 long (PGAM5L) and PGAM5 short (PGAM5S). PGAM5L mediates the association of PGAM5S with the RIP1/RIP3/MLKL necrosome complex (Fig. 1). PGAM5S is phosphorylated and subsequently activated by RIP3. Activated PGAM5S dephosphorylates dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) leading to activation of Drp1 and subsequent necrosis [11]. Knockdown of MLKL, PGAM5 or Drp1 largely impairs the necrosis induced by TNF [911]. Additionally, MLKL is required for sustained JNK activation and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [10], which induce necrosis via the PGAM5/Drp1 cascade [11]. 10. Conclusion TNF is one of the most important pro-inammatory cytokines, and plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of immune disorders and tumor development. Further understanding of TNFs actions and the mechanisms underlying TNF pathology will allow for the development of a new generation of anti-TNF therapies that will cause fewer side effects, yet still maintain high efcacy in the treatment of immune disorders and cancer-related inammation. Acknowledgments The author thanks Dr. Kyrie Felio for critically reading the manuscript. The author also apologizes for not referencing more papers due to the limitation in number. This work was supported by the NIH (R01AI54128 to WMC).

References

[1] M. Carbone, B.H. Ly, R.F. Dodson, I. Pagano, P.T. Morris, U.A. Dogan, A.F. Gazdar, H.I. Pass, H. Yang, Malignant mesothelioma: facts, myths, and hypotheses, J. Cell Physiol. 227 (2012) 4458. [2] J.B. Cordero, J.P. Macagno, R.K. Stefanatos, K.E. Strathdee, R.L. Cagan, M. Vidal, Oncogenic ras diverts a host TNF tumor suppressor activity into tumor promoter, Dev. Cell 18 (2010) 9991011. [3] E. Varfolomeev, T. Goncharov, H. Maecker, K. Zobel, L.G. Komuves, K. Deshayes, D. Vucic, Cellular inhibitors of apoptosis are global regulators of NF-kappaB and MAPK activation by members of the TNF family of receptors, Sci. Signal. 5 (2012) ra22. [4] B. Gerlach, S.M. Cordier, A.C. Schmukle, C.H. Emmerich, E. Rieser, T.L. Haas, A.I. Webb, J.A. Rickard, H. Anderton, W.W. Wong, U. Nachbur, L. Gangoda, U. Warnken, A.W. Purcell, J. Silke, H. Walczak, Linear ubiquitination prevents inammation and regulates immune signalling, Nature 471 (2011) 591596. [5] F. Ikeda, Y.L. Deribe, S.S. Skanland, B. Stieglitz, C. Grabbe, M. Franz-Wachtel, S.J. van Wijk, P. Goswami, V. Nagy, J. Terzic, F. Tokunaga, A. Androulidaki, T. Nakagawa, M. Pasparakis, K. Iwai, J.P. Sundberg, L. Schaefer, K. Rittinger, B. Macek, I. Dikic, SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-kappaB activity and apoptosis, Nature 471 (2011) 637641. [6] F. Tokunaga, T. Nakagawa, M. Nakahara, Y. Saeki, M. Taniguchi, S. Sakata, K. Tanaka, H. Nakano, K. Iwai, SHARPIN is a component of the NF-kappaBactivating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex, Nature 471 (2011) 633 636. [7] J.N. Dynek, T. Goncharov, E.C. Dueber, A.V. Fedorova, A. Izrael-Tomasevic, L. Phu, E. Helgason, W.J. Fairbrother, K. Deshayes, D.S. Kirkpatrick, D. Vucic, CIAP1 and UbcH5 promote K11-linked polyubiquitination of RIP1 in TNF signalling, EMBO J 29 (2010) 41984209. [8] M. Moulin, H. Anderton, A.K. Voss, T. Thomas, W.W. Wong, A. Bankovacki, R. Feltham, D. Chau, W.D. Cook, J. Silke, D.L. Vaux, IAPs limit activation of RIP kinases by TNF receptor 1 during development, EMBO J 31 (2012) 16791691. [9] L. Sun, H. Wang, Z. Wang, S. He, S. Chen, D. Liao, L. Wang, J. Yan, W. Liu, X. Lei, X. Wang, Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase, Cell 148 (2012) 213227. [10] J. Zhao, S. Jitkaew, Z. Cai, S. Choksi, Q. Li, J. Luo, Z.G. Liu, Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Am. 109 (2012) 53225327. [11] Z. Wang, H. Jiang, S. Chen, F. Du, X. Wang, The mitochondrial phosphatase PGAM5 functions at the convergence point of multiple necrotic death pathways, Cell 148 (2012) 228243.

Вам также может понравиться

- PAA CellCultureMediaДокумент20 страницPAA CellCultureMediaNilabh Ranjan100% (1)

- Vikram SarathyДокумент3 страницыVikram SarathyNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Ar 2011Документ116 страницAr 2011Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- A Protective Role by Interleukin-17F in Colon TumorigenesisДокумент8 страницA Protective Role by Interleukin-17F in Colon TumorigenesisNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- IL 17 CytokineReview2003Документ20 страницIL 17 CytokineReview2003Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Receptor Signalling Review2010Документ24 страницыReceptor Signalling Review2010Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Review IL-17 Signalling 2011Документ14 страницReview IL-17 Signalling 2011Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Collins 2008 IL-17 in Inflammation and AutoimmunityДокумент16 страницCollins 2008 IL-17 in Inflammation and AutoimmunityNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- IL-17F in InflammationДокумент12 страницIL-17F in InflammationNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Gaffen 2004 Functional Cooperaton Between IL-17 and TNFalpha Viy CCAATДокумент9 страницGaffen 2004 Functional Cooperaton Between IL-17 and TNFalpha Viy CCAATNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Cheng Et Al 2006 - Act - Il-17rДокумент5 страницCheng Et Al 2006 - Act - Il-17rNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Hirano T 2008 IL-17 Autoimmunity Feedback Loop IL-6Документ9 страницHirano T 2008 IL-17 Autoimmunity Feedback Loop IL-6Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- IL-17 Structure ReviewДокумент15 страницIL-17 Structure ReviewNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- 2002 VanderSpek Structure Function Analysis of Interleukin 7 Requirement For An Aromatic Ring at Position 143 of Helix DДокумент7 страниц2002 VanderSpek Structure Function Analysis of Interleukin 7 Requirement For An Aromatic Ring at Position 143 of Helix DNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- 1992 Kruse Conversion of Human Interleukin-4 Into A High Affinity Antagonist by A Single Amino Acid ReplacementДокумент8 страниц1992 Kruse Conversion of Human Interleukin-4 Into A High Affinity Antagonist by A Single Amino Acid ReplacementNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- 1994T 1Документ7 страниц1994T 1Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Comparative Model Building of Interleukin-7 Using Interleukin-4 As A Template: A Structural Hypothesis That Displays Atypical Surface Chemistry in Helix D Important For Receptor ActivationДокумент11 страницComparative Model Building of Interleukin-7 Using Interleukin-4 As A Template: A Structural Hypothesis That Displays Atypical Surface Chemistry in Helix D Important For Receptor ActivationNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- 2004 Krause Bacteria Displaying Interleukin-4 Mutants Stimulate Mammalian Cells and Reflect The Biological Activities of Variant Soluble CytokinesДокумент7 страниц2004 Krause Bacteria Displaying Interleukin-4 Mutants Stimulate Mammalian Cells and Reflect The Biological Activities of Variant Soluble CytokinesNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Holdenrieder Cancer Apoptosis Review 2004Документ13 страницHoldenrieder Cancer Apoptosis Review 2004Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- PNAS 2012 McElroy 1116582109Документ6 страницPNAS 2012 McElroy 1116582109Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Bortner Apoptotic Volume 2009Документ4 страницыBortner Apoptotic Volume 2009Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Ars 2009 2816Документ32 страницыArs 2009 2816Nilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- ScienceDirect - Lung Cancer - Stat3 Downstream Genes Serve As Biomarkers inДокумент3 страницыScienceDirect - Lung Cancer - Stat3 Downstream Genes Serve As Biomarkers inNilabh RanjanОценок пока нет

- Pfizer JobsДокумент2 страницыPfizer JobsNilabh Ranjan100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- On The Purpose of A Liberal Arts EducationДокумент9 страницOn The Purpose of A Liberal Arts EducationSyairah Banu DjufriОценок пока нет

- Biology (Grade 1, Semester 1)Документ69 страницBiology (Grade 1, Semester 1)Ahmed Mohamed Shawky NegmОценок пока нет

- Read Up 2 - Word ListsДокумент43 страницыRead Up 2 - Word ListsHANAОценок пока нет

- First-Page-Pdf 2Документ1 страницаFirst-Page-Pdf 2Luc CardОценок пока нет

- Catalogo Nuevo GboДокумент7 страницCatalogo Nuevo GboCaro ErazoОценок пока нет

- Low-Cycle Fatigue Behavior of 3d-Printed PLA-based Porous ScaffoldsДокумент8 страницLow-Cycle Fatigue Behavior of 3d-Printed PLA-based Porous ScaffoldskaminaljuyuОценок пока нет

- Common Model Exam Set-XV (B) (2079-4-14) QuestionДокумент16 страницCommon Model Exam Set-XV (B) (2079-4-14) QuestionSameer KhanОценок пока нет

- Spot Junior Booklet - Class VI To VIII 9268 PDFДокумент54 страницыSpot Junior Booklet - Class VI To VIII 9268 PDFArchanaGupta100% (1)

- 17 3Документ30 страниц17 3Lim ZjianОценок пока нет

- 23andme and The FDAДокумент4 страницы23andme and The FDAChristodoulos DolapsakisОценок пока нет

- CloveДокумент53 страницыCloveDharun RanganathanОценок пока нет

- The Characterization of 2 - (3-Methoxyphenyl) - 2 - (Ethylamino) Cyclohexanone (Methoxetamine)Документ15 страницThe Characterization of 2 - (3-Methoxyphenyl) - 2 - (Ethylamino) Cyclohexanone (Methoxetamine)0j1u9nmkv534vw9vОценок пока нет

- 2016 Black Soldier Fly WartazoaДокумент11 страниц2016 Black Soldier Fly WartazoaghotamaОценок пока нет

- Makalah SleДокумент48 страницMakalah Slesalini_sadhna17Оценок пока нет

- Cosmetics PresentationДокумент7 страницCosmetics PresentationOkafor AugustineОценок пока нет

- Anthropology For NTA UGC-NET JRF (Ganesh Moolinti) (Z-Library)Документ184 страницыAnthropology For NTA UGC-NET JRF (Ganesh Moolinti) (Z-Library)Debsruti SahaОценок пока нет

- GS 631 - Library and Information Services (0+1) : TopicsДокумент24 страницыGS 631 - Library and Information Services (0+1) : TopicsVivek KumarОценок пока нет

- Name of Disease: Apple ScabДокумент18 страницName of Disease: Apple Scabapi-310125081Оценок пока нет

- AQUATICS Keeping Ponds and Aquaria Without Harmful Invasive PlantsДокумент9 страницAQUATICS Keeping Ponds and Aquaria Without Harmful Invasive PlantsJoelle GerardОценок пока нет

- 12 Biology Notes Ch11 Biotechnology Principles and ProcessesДокумент9 страниц12 Biology Notes Ch11 Biotechnology Principles and ProcessesAnkit YadavОценок пока нет

- GDR - Poc Update (01.07.21)Документ2 страницыGDR - Poc Update (01.07.21)Dr ThietОценок пока нет

- Woody Plant Seed ManualДокумент1 241 страницаWoody Plant Seed ManualElena CMОценок пока нет

- Hemastix Presumptive Test For BloodДокумент2 страницыHemastix Presumptive Test For BloodPFSA CSIОценок пока нет

- Charles Horton Cooley PDFДокумент5 страницCharles Horton Cooley PDFArXlan Xahir100% (4)

- Science SNC2D Grade 10 ExamДокумент8 страницScience SNC2D Grade 10 ExamRiazОценок пока нет

- Shimelis WondimuДокумент95 страницShimelis WondimuMelaku MamayeОценок пока нет

- Capsule Research ProposalДокумент13 страницCapsule Research ProposalTomas John T. GuzmanОценок пока нет

- BreathingДокумент10 страницBreathingOVVCMOULI80% (5)

- B.SC Nursing 2018 Question Papers First Year English FR 2Документ2 страницыB.SC Nursing 2018 Question Papers First Year English FR 2Himanshu0% (1)

- Field Trip ReportДокумент28 страницField Trip ReportTootsie100% (1)