Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Theory Translation

Загружено:

Lungu DanielaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Theory Translation

Загружено:

Lungu DanielaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

O..

H

( )

HV

2008

O.I. Panchenko

THEO! "#$ %"&T'&E O( T"#)*"T'O#

(*+,-./+ #0-+1 234 T+1-1)

HV

2008

Lecture 1

THEO! O( T"#)*"T'O# ") " )&'E#&E

Translation and art are twin processes.

Octavio Pas

PLAN

1. The subject and tasks oI the science.

T5+ 1.67+,- 234 -2181 09 -5+ 1,:+3,+;

Translation is a peculiar type oI communication interlingual communication.

The goal oI translation is to transIorm a text in the Source Language into a text

in the Target Language. This means that the message produced by the translator

should call Iorth a reaction Irom the TL receptor similar to that called Iorth by the

original message Irom the SL receptor. The content, that is, the reIerential meaning oI

the message with all its implications and the Iorm oI the message with all its emotive

and stylistic connotations must be reproduced as Iully as possible in the translation as

they are to evoke a similar response. While the content remains relatively intact, the

Iorm, that is, the linguistic signs oI the original, may be substituted or replaced by

other signs oI the TL because oI structural diIIerences at all levels. Such substitutions

are justiIied; they are Iunctional and aim at achieving equivalence.

Equivalent texts in the two languages are not necessarily made up oI

semantically identical signs and grammatical structures and equivalence should not

be conIused with identity.

LECTURE

EQUIVALENCE

Equivalence is the reproduction of a SL text by TL means. Equivalence is not

a constant but a variable quantity and the range oI variability is considerable. The

degree oI equivalence depends on the linguistic means used in the SL texts and on the

Iunctional style to which the text belongs. E.g.:

Early December brought a brief respite when temperatures fell and the ground

hardened, but a quick thaw followed.

!" #"$%&' ()*+,! $&)$' +"&"#-.$, )"/+"&)*&

+0,1,!(2, 1"/!' 1/"&1!, 0 +0)0/ %-()&0 !(2 0))"+"!2.

The messages conveyed by the original and the translaton are equivalent as

every semantic element has been retained although some changes have been made in

strict conIormity with the standards and usage oI the Russian language.

T!%E) O( E<='>"*E#&E

Equivalence implies variability and consequently several types oI equivalence

can be distinguished.

(:/1- T?@+ A (0/B2C ED.:E2C+3,+;

3hildren go to school e4ery morning.

5"), 60#') 7 .$0!* $8#0" *)&0.

The content, the structure oI the sentence and the semantic components

(language units) are similar. Each element oI the SL text has a corresponding one in

the TL text. But such cases oI complete similarity are rather rare.

)+,034 T?@+ A %2/-:2C &0//+1@034+3,+ ED.:E2C+3,+;

Non-corresponding elements may be lexical, grammatical or stylistical.

Equivalence oI the second type is usually achieved by means oI various

transIormations: substitution or replacements (both lexical and grammatical),

additions and omissions, paraphrasing and compensation.

9ll through the long foreign summer the 9merican tourist abroad has been

depressed by the rubber quality of his dollar.

0 7&"/' +&0#0!8,)"!20:0 !")":0 +&"%-7,' 1 :&,;"<

/"&,$($,6 )*&,()07 *:")!0 "+&"&-70" (0$&="," +0$*+)"!20<

(+0(0%0(), #0!!&.

Although a considerable degree oI equivalence has been achieved a number oI

transIormations, certain losses have been incurred, namely, compactness and

vividness. They are accounted Ior by existing discrepancies in collocability (valency).

Attention should be paid to the Stylistic aspect oI equivalence because oI its

importance in achieving the second type oI equivalence. The stylistic aspect oI

equivalence implies the rendering in translation oI stylistic and emotive connotations.

Stylistic connotations presuppose the use oI words belonging to the same layer oI the

vocabulary (literary, neutral and colloquial). Emotive connotations presuppose the

use oI words evoking similar connotations. The Iollowing example illustrates the

rendering oI stylistic connotations:

Delegates to the conference in >an ?rancisco, 9pril, @ABC, from European

countries ha4e been tra4eling three weeks. The Derman EFboats which were hanging

around were most effecti4ely scared off by depthFcharges from accompanying

destroyers.

5"!":)- ,1 "7&0+"<($,6 ()& G0H"&";,I 7 JFK&;,($0,

0)$&-7.*I(' 7 +&"!" @ABC :., 60#,!,(2 7 +*), +0), )&, "#"!,.

L!*%,-" %0/%- (0+&0708#7.,6 M(/,;"7 *(+".0 0):0'!, :"&/($,"

+0#70#-" !0#$,, $0)0&-" 7(" "=" .-&'!, 7 0$"".

The coll

erN.

O02I +&0608," 7,#"!, "()"&+,/0F'&$,< /"&)7"-< (7") "

+&,$&-)0:0 =,)0/ *!,0:0 H0&'.

Attention should also be drawn to the Pragmatic aspect oI equivalence.

Pragmatic equivalence can be achieved only by means oI interpreting extra-

linguistic Iactors.

Pr. Qealey by his decision presented a 3hristmas package so small that it is

hardly e4en a 3hristmas stockingFfiller.

R"&-, $0)0&-" &".,!(' /,,()& H,(07 S,!, +"&"# (/-/

&08#"()70/, %-!, )$,/, $*;-/,, )0 ,6 "#7 !, /080 17)2

&08#"()7"($,/ +0#&$0/.

The literal translation oI 'a 3hristmas stockingFfiller ')0 0, "#7 !,

/0:!, +0!,)2 &08#"()7"($,< *!0$ would hardly convey any sense to the

Russian receptor unIamiliar with the custom. In this case the pragmatic aspect

motivated the translation 'a 3hristmas stockingFfiller by '&08#"()7"($,<

+0#&0$. The addition oI the words '/,,()& H,(07 is also necessitated by

pragmatic considerations.

Here is another example oI interesting substitution.

The Elgin marbles seem an indisputable argument in fa4or of the preser4ation

of works of art by rape.

J))*, , H&,1, (')-" !0�/ T!:,0/ ( U&H"0 , *7"1"-" 7

V:!,I, +0F7,#,/0/*, '7!'I)(' "0+&07"&8,/-/ #070#0/ 7 +0!21* (06&",'

+&0,17"#",< ,($*(()7 +*)"/ 6,=",'.

The substitution oI the subject and the addition oI the participle construction

convey the necessary pragmatic inIormation. II a detail denoting some national

Ieature is not important enough it may saIely be omitted, e.g.

Qe could take nothing for dinner but a partridge with an imperial pint of

champagne WX. DalsworthyN.

Y 0%"#0/ 0 (Z"! )0!2$0 $*&0+)$* , 1+,! "" %*)-!$0< ./+($0:0.

The word 'imperial does not convey any signiIicant inIormation and may

thereIore be omitted in the Russian translation without impairing equivalence.

The pragmatic aspect oI the content is sometimes closely interwoven with the

linguistic aspect and their interaction also requires explanatory additions, e.g.

[ was sent to a boarding school when [ was 4ery little \ about fi4e \ because

my mother and father ] couldn^t afford anything so starchy as an English nurse or a

?rench go4erness W[lka 3haseN.

R"' 0)+&7,!, 7 +(,0, $0:# ' %-! 0"2 /!"2$0<, /" %-!0 !")

+')2, +0)0/* )0 /0, &0#,)"!, " /0:!, +0170!,)2 ("%" , ()0'="<

:!,<($0< '2$, 7 $&6/!"0/ "+;" , +"&"#,$", , 0+0&0<

H&;*1($0< :*7"&)$,.

The diIIiculty there lies not only in the pragmatic aspect oI the adjective

'starchy but also in its use in two meanings, direct and indirect, simultaneously (@.

$&6/!"-<_ `. 0+0&-<).

T5:/4 T?@+ A ):-.2-:032C 0/ (2,-.2C ED.:E2C+3,+;

The content or sense oI the utterance is conveyed by diIIerent grammatical and

lexical units.

Situational equivalence is observed when the same phenomenon is described in

a diIIerent way because it is seen Irom a diIIerent angle, e.g.

The police cleared the streets.

U0!,;,' &10:! #"/0()&;,I .

Enemployed teenagers are often left without means of gaining food and

shelter.

a"1&%0)-" +0#&0()$, ()0 0$1-7I)(' %"1 (&"#()7 $

(*="()707,I.

Qold the line.

O" $!#,)" )&*%$*.

The 3ommonwealth countries handle a quarter of the world^s trade.

O ()&- %&,)($0:0 (0#&*8"()7 +&,60#,)(' ")7"&)' ()2

/,&070< )0&:07!,.

This type oI equivalence also comprises the translation oI cliches, orders,

warnings and notices, phraseological units and set expressions, Iormulae oI

politeness, etc.

There were no sur4i4ors.

(" +0:,%!,.

?ragile \ 0()0&080, ()"$!0_

beep off, wet paint \ " (#,)2(', 0$&."0_

Pany happy returns of the day \ +01#&7!'I ( #"/ &08#",'.

In this way, the third type oI equivalence conveys the sense, the meaning oI the

utterance without preserving its Iormal elements.

(For a detailed analysis oI the levels oI equivalence problems and the structural

level patterns the reader is reIerred to the studies oI Soviet linguists B.H.

and B.H. tx , t. 203, .

183-199).

*E>E*) O( E<='>"*E#&E

Equivalence may occur at diIIerent linguistic levels: phonetic, word building,

morphological, at word level, at phrase level, at sentence level and Iinally at text

level.

%503+-:, C+E+C 09 ED.:E2C+3,+

The sound Iorm oI corresponding English and Russian words seldom coincide,

consequently this level oI equivalence is not common and is oI primary importance

only in poetic translation.

F0/4G6.:C4:3H *+E+C 09 ED.:E2C+3,+

e.g.: irresponsible \ %"10)7")()7"-<_ unpredictable \ "+&"#($1*"/-<_

counterbalance \ +&0),707"(, t.

I0/@50C0H:,2C *+E+C 09 ED.:E2C+3,+

e.g.: The report^s proposals were handed to a political committee.

U&"#!08",' #0$!# %-!, +"&"#- +0!,),"($0/* $0/,)")*.

ED.:E2C+3,+ 2- F0/4 *+E+C

e.g.: >he clasped her hands round her handbag. (Agatha Christie).

c $&"+$0 (8! 7 &*$6 (70I (*/0$*.

ED.:E2C+3,+ 09 %5/21+ *+E+C

Equivalence at phrase level is oI two kinds: a SL word corresponds to a TL

phrase (to negotiate \ 7"(), +"&":070&-), a SL phrase corresponds to a TL word

(Qippies are in re4olt against an acquisiti4e society. \ S,++, 70(()I) +&0),7

+0)&"%,)"!2($0:0 0%="()7).

ED.:E2C+3,+ 2- )+3-+3,+ *+E+C

It occurs: a) in phraseology two is company, three is none \ )&"),<

!,.,<; b) in orders and regulations keep off the grass \ +0 :10* " 60#,)2.

ED.:E2C+3,+ 2- T+J- *+E+C

It is usual in the translation oI poetry as seen in the translation oI William

Blake`s stanza by S. Marshak.

@. To see a dorld in a Drain of >and,

`. 9nd a Qea4en in a dild ?lower,

e. Qold [nfinity in the palm of your hand,

4. 9nd Eternity in an hour. (W. Blake, Auguries oI Innocence)

B. 0#0 /:07"2" 7,#")2 7"0()2,

@. c:&0/-< /,& \ 7 1"&" +"($,

e. "#,0< :0&(), \ %"($0"0()2

`. f "%0 \ 7 ."$" ;7")$.

The translation by S.Marshak may be regarded as excellent. The text as a unity

is reproduced most Iully and this conception oI unity justiIies the change in the order

oI the lines within the stanza.

A strict observance oI equivalence at all levels ensures a similar reaction on the

part oI the S and T language receptors and can be achieved by means oI Iunctional

substitutions.

LECTURE

T!%E) O( T"#)*"T'O#

Good theory is based on inIormation gained Irom practice. Good practice is based on

careIully worked-out theory. The two are interdependent. (Larson l991, p. 1)

The ideal translation will be accurate as to meaning and natural as to the receptor

language Iorms used. An intended audience who is unIamiliar with the source text

will readily understand it. The success oI a translation is measured by how closely it

measures up to these ideals.

The ideal translation should be.

Accurate: reproducing as exactly as possible the meaning oI the source text.

Natural: using natural Iorms oI the receptor language in a way that is

appropriate to the kind oI text being translated.

Communicative: expressing all aspects oI the meaning in a way that is readily

understandable to the intended audience.

Translation is a process based on the theory that it is possible to abstract the meaning

oI a text Irom its Iorms and reproduce that meaning with the very diIIerent Iorms oI a

second language.

Translation, then, consists oI studying the lexicon, grammatical structure,

communication situation, and cultural context oI the source language text, analyzing

it in order to determine its meaning, and then reconstructing this same meaning using

the lexicon and grammatical structure which are appropriate in the receptor language

and its cultural context. (Larson l998, p. 3)

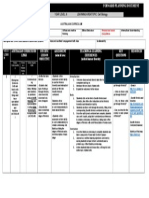

Diagram from garson lAAh, p. B

In practice, there is considerable variation in the types oI translations produced by

translators. Some translators work only in two languages and are competent in both.

Others work Irom their Iirst language to their second language, and still others Irom

their second language to their Iirst language. Depending on these matters oI language

proIiciency, the procedures used will vary Irom project to project. In most projects in

which SIL is involved, a translation team carries on the project. Team roles are

worked out according to the individual skills oI team members. There is also some

variation depending on the purpose oI a given translation and the type oI translation

that will be accepted by the intended audiences.

Good theory is based on inIormation gained Irom practice. Good practice is based on

careIully worked-out theory. The two are interdependent. (Larson l991, p. 1)

The ideal translation will be accurate as to meaning and natural as to the receptor

language Iorms used. An intended audience who is unIamiliar with the source text

will readily understand it. The success oI a translation is measured by how closely it

measures up to these ideals.

The ideal translation should be.

Accurate: reproducing as exactly as possible the meaning oI the source text.

Natural: using natural Iorms oI the receptor language in a way that is

appropriate to the kind oI text being translated.

Communicative: expressing all aspects oI the meaning in a way that is readily

understandable to the intended audience.

Translation is a process based on the theory that it is possible to abstract the meaning

oI a text Irom its Iorms and reproduce that meaning with the very diIIerent Iorms oI a

second language.

Translation, then, consists oI studying the lexicon, grammatical structure,

communication situation, and cultural context oI the source language text, analyzing

it in order to determine its meaning, and then reconstructing this same meaning using

the lexicon and grammatical structure which are appropriate in the receptor language

and its cultural context. (Larson l998, p. 3)

Diagram from garson lAAh, p. B

In practice, there is considerable variation in the types oI translations produced by

translators. Some translators work only in two languages and are competent in both.

Others work Irom their Iirst language to their second language, and still others Irom

their second language to their Iirst language. Depending on these matters oI language

proIiciency, the procedures used will vary Irom project to project. In most projects in

which SIL is involved, a translation team carries on the project. Team roles are

worked out according to the individual skills oI team members. There is also some

variation depending on the purpose oI a given translation and the type oI translation

that will be accepted by the intended audiences.

The Iollowing three types oI translation can be distinguished: equivalent

translation, literal translation and Iree translation.

ED.:E2C+3- -/231C2-:03

Equivalent translation has been considered in the preceding pages. Achieving

equivalence is the goal aimed at in translation.

*:-+/2C -/231C2-:03

In spite oI the Iact that there are cases oI semantic and structural coincidences

they are rather an exception. A literal or word translation is obviously unacceptable

because it results in a violation oI Iorm, or a distortion oI sense, or both.

No desire on the part oI the translator to preserve in his translation the lexical,

grammatical or stylistic peculiarities oI the original text can justiIy any departure

Irom the norms oI the TL.

Literal translation imposes upon the TL text alien lexical and grammatical

structures, alien collocability, alien connotations and alien stylistic norms.

In literal translation Iorm prevails over content and the meaning oI the text is

distorted. Literalism may be lexical, grammatical or stylistic, e.g.

Qe wagged a grateful tail and climbed on the seat (Georgetta Heyer).

c %!:0#&0 17,!'! 670()0/ , 7($&%$!(' (,#"2"I

>he was letting her temper go by inches (Monica Dickens).

c +0"/0:* )"&'! )"&+",". Wc 7(" %0!2." , %0!2." )"&'!

)"&+","N.

The pragmatic aspect oI translation does not admit literalism either and

requires interpreting translation or substitution.

The Tory Team, howe4er, aren^t all batting on the same wicket.

The metaphor is taken from cricket, a 4ery popular game in iritain but hardly

known to jussian readers.

c#$0, $0("&7)0&- " "#,-.

c#$0, $0/# $0("&7)0&07 ,:&! " #&*80.

T/231C2-:03 *0231

Literal translation should not be conIused with translation loans. A translation

loan is a peculiar Iorm oI word-borrowing by means oI literal translation. Translation

loans are built on the pattern oI Ioreign words or phrases with the elements oI the

borrowing language, e.g. collecti4e farm is a translation loan oI the Russian $0!601

but in a Iull and not in an abbreviated Iorm: oil dollars F"H)"#0!!&-_

goodneighbourly relations \ #0%&0(0("#($," 0)0.",' (a Iull loan)_ war effect (a

partial loan as number does not coincide).

(/++ T/231C2-:03

Free translation, that is, paraphrasing is a special type oI translation used as a

rule in annotations, precis, abstracts, etc. Iree translation is rendering oI meaning

regardless oI Iorm. The aim oI such translation is to convey inIormation to people in

other countries in a most compact and condensed manner.

There is another interpretation oI the term 'Free translation.

The translator in this case considers himselI as co-author and takes great

liberties with the original text resorting to unjustiIied expansion or omissions.

k>he burst out cryingl is translated as 'Ct x

m (Ch. Dickens, tr. By J.V. Vedensky).

TO CONCLUDE: the three parameters oI translation are: rendering oI

contents, rendering oI Iorm and observance oI TL norms. These Iundamentals are oI

equal signiIicance and are to be duly taken into account in the process oI translation.

The vast resources oI the Russian language enable the translator to achieve excellent

and the Iundamental principle oI translation what is said in one language can as

well be said in another remains inviolable.

LECTURE

K"II"T'&"* %OL*EI)

K+3+/2C ,031:4+/2-:031

Equivalence, as has been pointed in the previous chapter, is achieved by

diIIerent transIormations: grammatical, lexical, stylistic. The present chapter deals

with grammatical transIormations and their causes. The causes generating these

transIormations are not always purely grammatical but may be lexicalas well, though

grammatical causes naturally prevail due to diIIerences in the SL and TL

grammatical structures.

Not inIrequently, grammatical and lexical causes are so closely interwoven that

the required transIormations are oI a twoIold character. The Iollowing example

illustrates this point.

The 4igil of the E.>. Embassy supported last week by many prominent people

and still continuing, the marches last >aturday, the resolutions of organimations ha4e

done something to show that the nrime Pinister does not speak for iritain.

G&*:!0(*)0' #"/0()&;,' * 1#,' /"&,$($0:0 +0(0!2()7,

+0!*,7.' +&0.!0< "#"!" +0##"&8$* /0:,6 7,#-6 #"')"!"<, 7(" "="

+&0#0!8")('. T) #"/0()&;,' , (0()0'7.,"(' 7 (*%%0)* +060#-,

)$8" +&,')-" &1!,-/, 0&:,1;,'/, &"10!I;,,, '70

(7,#")"!2()7*I) 0 )0/, )0 +&"/2"&F/,,()& 0)I#2 " :070&,) 0) ,/",

7(":0 :!,<($0:0 &0#.

A number oI lexical and grammatical transIormations have been eIIected in: 1)

the long English sentence in which the subject is expressed by three homogeneous

members (the 4igil, the marches, the resolutions) is translated by two separate

Russian sentences. The structure oI the English sentence is typical oI the structure oI

brieI notes or oI leads which usually contain miscellaneous inIormation on the

principles oI 'who, what, when, where and how. This, however, is not usual in

Russian newspaper style. The word #"/0()&;,' is repeated as both sentences

have the same subject. 2) The word '4igil has recently developed a new meaning

'around the clock demonstration. This new meaning is accordingly rendered by two

words ($&*:!0(*)0' #"/0()&;,'); similarly, the participle 'supported is also

rendered by two Russian words (+0!*,7.' +0##"&8$*); 3) a number oI additional

words have been introduced: * 1#,' W+0(0!2()7N, (0()0'7.,"(' W7 (*%%0)*

+060#-N, )$8" +&,')-" &1!,-/, W0&:,1;,'/, &"10!I;,,N. 4) The

word 'last has been omitted as its meaning is implied in the Russian adverbial oI

time (7 (*%%0)*); 5) The emphatic meaning oI the predicate with its object (ha4e

done something to show) is conveyed by the adverb '70. 6) The cliche (speak for

iritain) is rendered by a corresponding cliche :070&,)2 0) ,/",. 7) Finally, the

metonymy (iritain) is translated by the words it stands for 7"(2 :!,<($,< &0#.

Strictly speaking only the translation oI the complex sentence by meaning oI

two sentences can be regarded as a purely grammatical transIormation, whereas all

the other transIormations are oI a mixed character both lexical and grammatical.

K/2BB2-:,2C (+2-./+1 T?@:,2C 09 I04+/3 E3HC:15

Naturally only some Ieatures oI Modern English will be considered here.

The deeply rooted tendency Ior compactness has stimulated a wide use oI

various verbal complexes: the inIinitive complex, the gerundial complex, the

participial complex, the absolute nominative construction. The same tendency is

displayed in some pre-positional attributes: the N1 N2 attributive model, attributive

groups, attributive phrases. None oI them has any equivalents in Russian grammar

and as a rule they require decompression in translation. Causative constructions also

illustrate this tendency Ior compactness.

Qe ]soon twinkled naul out of his sulks (R.F.DalderIield).

c ! +0#/,:,7)2 U0!I , )0) +"&"()! #*)2('.

Translation is sometimes impeded by the existence oI grammatical homonymy

in Modern English. For example, the Gerund and Participle I are homonyms. The

analytical Iorms oI the Future-in-the-Past are homonyms with the Iorms oI the

Subjunctive mood: should (would) inIinitive. The diIIiculty is aggravated by a

homonymous Iorm oI the Past IndeIinite oI the verb 'will expressing volition. The

InIinitive oI Purpose and the InIinitive oI Subsequent Action may easily be conIused.

Grammatical homonymy may oIten be puzzling and may sometimes cause diIIerent

interpretations. In such cases recourse should be taken to a wider context, e.g.

dhat we stand for is winning all o4er the world. (L. Barkhudarov, Lectures).

The translation oI the sentence depends on the grammatical interpretation oI

the ing Iorm, i.e. whether it is interpreted as Participle I or as a Gerund. According

to the Iormer interpretation, the word combination 'is o winning is the Iorm oI the

Present Continuous Tense; according to the latter, it is a nominal predicate link verb

Predicative. These diIIerent interpretations result in diIIerent translations:

@. p0, 1 )0 /- 7-()*+"/, 0#"&8,7") +0%"#* 70 7("/ /,&".

`. R- ()0,/ 1 )0, )0%- #0%,)2(' +0%"#- 70 7("/ /,&".

A diIIerent grammatical interpretation involves a diIIerent political

interpretation.

#03G+D.:E2C+3-1

Some English grammatical Iorms and structures have no corresponding

counterparts in Russian, others have only partial equivalents. The Iirst group) non-

equivalents) includes articles, the gerund and the Past PerIect Tense.

Articles. The categories oI deIiniteness and indeIiniteness are universal but the

ways and means oI expressing these notions vary in diIIerent languages.

In English this Iunction is IulIilled by the articles whereas in Russian by word

order. Both the deIinite and indeIinite articles in English are meaningIul and their

meanings and their Iunctions cannot be ignored in translation.

Every utterance Ialls into two parts the so-called theme and rheme. The

theme indicates the subject oI the utterance while the rheme contains the inIormation

about the subject. The theme, in other words, represents a known thing, which has

probably been mentioned beIore, whereas the rheme introduces some new

inIormation. Thus the theme is the starting point oI the utterance and as such it can

sometimes introduce a new subject about which the rheme gives some inIormation. In

this case the indeIinite article is used to indicate indeIiniteness. The theme usually

occupies the initial position in the sentence. The theme in the English language with

its Iixed word order usually coincides with the grammatical subject oI the sentence.

When the theme again occurs in the text it is preceded by the deIinite article.

9 lady entered the compartment. The lady sat down in the corner seat

(P.G.Wodehouse).

The categories oI indeIiniteness and deIiniteness are expressed by the

indeIinite and the deIinite articles respectively and these categories are rendered by

word order in translation.

$*+" 70.! #/. 5/ ("! 7 *:!* * 0$.

When the articles are charged with some other meanings apart Irom the

categories oI deIiniteness and indeIiniteness lexical means come into play in

translation.

II these meanings are not rendered lexically the Russian sentence is

semantically incomplete.

The influence and authority of the >ecretariat depends to an eqtent Wthough not

nearly to the eqtent that is popularly supposedN on the talents of one indi4idual \ the

>ecretaryFDeneral. (Peter Lyon, The U.N. in Action).

!,'," , 7)0&,)") J"$&")&,) 17,(,) 7 $$0<F)0 ()"+", W60)'

, " 7 )$0< ()"+",, $$ 0%-0 (,)I)N 0) (+0(0%0()"< 0#0:0 "!07"$

\ L""&!20:0 ("$&")&'.

T5+ K+/.34; Another non-equivalent Iorm is the gerund. It IulIils various

Iunctions in the sentence and can be translated by diIIerent means.

k[ wonder at Xolion^s allowing this engagementl, he said to 9unt 9nn

(J. Galsworthy).

rs *#,7!'I(2, )0 580!,0 &1&".,! M)* +0/0!7$*t, \ ($1! 0

)")*.$" T.

The gerund modiIied by a proper noun in the possessive case is translated by a

subordinate clause.

The gerund used in the Iunction oI a prepositional object is also rendered in

translation by a subordinate clause.

The mayor of the island is talking of opening up its lush and 4irgin interior to

beefFandFdairy cattle ranching.

RM& 0()&07 +0:07&,7") 0 )0/, )0%- ,(+0!2107)2 (0-",

")&0*)-" !*: ":0 7*)&""< (), #!' /'(0/0!00:0 601'<()7.

The so-called halI-gerund may also be translated by a subordinate clause.

There was nothing more to sayu which didn^t pre4ent, as the game went on, a

good deal more being said. (G.F.Snow).

L070&,)2 %0!2." %-!0 " 0 "/, 0 M)0 " +0/".!0 )0/*, )0 7 60#"

,:&- %-!0 ($10 "=" 0"2 /0:0.

T5+ %21- %+/9+,- T+31+; The meaning oI the Past PerIect Tense is usually

rendered in Russian by some adverbs oI time.

The stone heat of the day had gentled down. (I.Shaw).

v&, $0)0&-< ."! #"/ 0) &($!"-6 $/"<, *8" (+!.

But in many cases the Past PerIect Tense is translated by the Russian Past

Tense without any temporal speciIication.

The mainspring of his eqistence was taken away when she died] Ellen was the

audience before which the blustering drama of Derald w^Qara had been played.

(M. Mitchell).

c+0& ":0 (*="()707,' ,("1! ( "" (/"&)2I. ]T!!, %-! )0<

+*%!,$0<, +"&"# $0)0&0< &1-:&-7!(2 %*&' #&/ 58"&!2# c^S&.

%2/-:2C ED.:E2C+3,+

SL and TL grammatical Iorms hardly ever coincide Iully. The scope oI their

meaning and their Iunctions and usage generally diIIer, thereIore these Iorms are

mostly partial equivalents.

The category oI number in English and in Russian is a casein point. Most oIten

the use oI the singular and the plural in the two languages coincides. But divergences

in the use oI the singular and the plural appear in the Iirst place in the so-called

Singularia and Pluralia Tantum, that is, in those nouns which have either only a

singular or a plural Iorm, e.g. gate \ 70&0), ink \ "&,!, money \ #"2:,, and

vice versa: gallows \ 7,("!,;, news \ 070(),. Sometimes a countable noun in

English and in Russian, E.G. talent \ talents_ )!) \ )!)- develops a new

LSV (lexical-semantic variant) which is used as an uncountable noun.

iritain is the source of phrase kbrain drainl which describes the mo4ement of

iritish talent to the Enited >tates.

-&8"," r*)"$ */07t, $0)0&0" 01") M/,:&;,I :!,<($,6

(+";,!,()07 7 J0"#,"-" x))-, 7+"&7-" +0'7,!0(2 7 "!,$0%&,),,.

Abstract nouns are more oIten used in the plural in English than in Russian,

e.g.

The struggles of many sections of the E.>. population against the warFlo4ers in

9merica ha4e grown to a height ne4er reached before.

a0&2% /0:,6 :&*++ ("!",' J0"#,"-6 x))07 +&0),7

()0&0,$07 70<- #0(),:! "%-7!0:0 &1/6.

9llende^s political skills made him four times candidate for the presidency.

U0!,),"($,< 0+-) V!2"#" 0%"(+",! ")-&"6$&)0" 7-#7,8"," ":0

$#,#)*&- +0() +&"1,#").

The semantic volume oI the word 'skills justiIies its translation by two

Russian words both used in the singular.

c+-) , ,($*(()70 V!2"#" $$ +0!,),"($0:0 #"')"!']

Sometimes diIIerent usage prevents a strict observance oI he category oI

number in translation, e.g.

The right to work is ensured by the democratic organimation of the national

economy, the growth of the producti4e forces and the elimination of crisis and

unemployment.

U&70 )&*# 0%"(+",7")(' #"/0$&),"($0< 0&:,1;,"<

&0#0:0 601'<()7, &0()0/ +&0,170#,)"!2-6 (,! , 0)(*)()7,"/ $&,1,(07

, %"1&%0),;-.

The plural Iorm in Russian ($&,1,(07) achieves the required degree oI

generalization.

There is also a tendency in English o use nouns like 'eye, 'cheek, 'lip, 'ear,

'limb, etc. in the singular, e.g.

Qe always thought of her as se4enteen or so, clean of limb, beautiful of feature

and filled with the impatience for life. (R. Wilder).

c 7(":# +&"#()7!'! "" ("%" $$0< 0 %-! !") 7 ("/#;)2 \

$&(,7-" "&)- !,;, ()&0<-" 0:, , %"1*#"&8' 88# 8,1,.

The noun 'limb can also be rendered metonymically +&"!"()' H,:*&.

There is also a considerable diIIerence between the use oI the Passive voice in

English and in Russian. The English language allows diIIerent types oI passive

constructions and there are a number oI verbs in English which can be used in the

passive voice while the correlated verbs in Russian cannot. For example, many

English verbs are used both as transitive and intransitive.

wriginal samples of naris clothing ha4e been flown to gondon to illustrate

lectures to the fashion industry.

O07-" /0#"!, +&,8($,6 )*!")07 %-!, #0()7!"- (/0!")0/ 7

y0#0 #!' +0$1 70 7&"/' !"$;,< +&"#()7,)"!'/ :!,<($,6 #0/07 /0#"!"<.

English verbs with a prepositional object are also used in the passive voice, a

construction non-existing in Russian.

go4ers if familiar symphonic fare are catered for with two irahms symphonies

and ?irst niano 3oncerto by ieetho4en.

yI%,)"!"< ()0 ,(+0!'"/0< (,/H0,"($0< /*1-$, 7 -"."/

("10" *:0=I) #7*/' (,/H0,'/, a&/( , U"&7-/ H0&)"+,-/

$0;"&)0/ a")607".

The impersonal passive with a preposition is translated by an impersonal

construction.

The increase in the family allowances that was widely hoped for has come to

nothing.

z7"!,"," +0(0%,' /0:0#")-/ ("/2'/, $0)0&0" 7(" )$ #"'!,(2,

" 0(*="()7,!0(2.

In some cases the use oI the Russian Passive Iorm is precluded by the Iact that

the Russian verb is used with a prepositional object.

The [ran earthquake was followed by tremors lasting a long time.

Y 1"/!")&'(","/ 7 f&" +0(!"#07!, )0!$,, +&0#0!87.,"('

#070!20 #0!:0.

Verbs Iormed by conversion present great diIIiculties in translation especially

when used in the Passive.

The roads were sentinelled by oaks. (Clemance Dane).

U0 $&'/ #0&0:,, (!070 (07-", ()0'!, #*%-.

Its picturesqueness is rendered by a simile which makes the translation

semantically and stylistically equivalent.

The desire Ior giving prominence to some element oI the utterance, oIten

accounts Ior the use oI the passive Iorm in English. As the word order is Subject-

Predicate-Object and as stylistic inversion is relatively inIrequent because oI its

expressive value, the Passive is naturally used. The tendency is particularly marked in

newspaper style.

?ears are eqpressed that the {orth >ea could be fished out of herring.

-($1-7I)(' 0+(",', )0 ,1 J"7"&0:0 /0&' /0:*) 7-!07,)2 7(I

("!2#2.

>+/62C1 the InIinitive and the Participles.

Though these categories also exist in Russian there are considerable diIIiculties

in their Iorms and their use: the English InIinitive has PerIect and Continuous Iorms

which are absent in the Russian language, whereas these verbals in the Russian

language have perIective and imperIective aspects, non-existent in English. There are

inIinitive and participle complexes in Englishwhich have no counterparts in Russian.

T5+ '39:3:-:E+; Nominative with the inIinitive (the inIinitive as a secondary

predicate).

wil consumption has increased by B per cent and the increase is eqpected to go

up to C per cent.

U0)&"%!"," "H), 701&0(!0 B +&0;") , 08,#")(', )0 00

#0(),:") C +&0;")07.

The inIinitive complex is rendered by two clauses.

The nfinitive complex with the preposition !for".

That was an odd thing for him to do. (G.Grene).

J)&0, )0 0 )$ +0()*+,!.

The inIinitive complex is translated by a subordinate clause.

The nfinitive used as attribute.

>upporters of outright independence for nuerto jico fared poorly in the

election \ but remained a force to contend with.

J)0&0,$, "/"#!"0:0 +&"#0()7!",' "17,(,/0(), U*M&)0F|,$0

(0%&!, "1,)"!20" ,(!0 :0!0(07 7-%0&6, 0 0, 7(" 8"

+&"#0()7!'I) (0%0< (,!*, ( $0)0&0< +&,#")(' (,))2('.

Here too, the inIinitive is translated by a subordinate attributive clause

comprising the inIinitive itselI.

The nfinitive of subsequent action.

Throughout @Ae} term after team after team attacked the Eiger, only to be

dri4en back. (Trevanian).

O +&0)'8",, 7(":0 @Ae} :0# 0# :&*++ !2+,,()07 1 #&*:0<

+-)!(2 (07"&.,)2 70(608#"," 7"&.,* T<:"& , $8#-< &1 7(" 0,

%-!, 7-*8#"- 0)()*+)2.

The InIinitive is rendered in this case by a coordinate clause.

T5+ %2/-:,:@C+ 21 %2/- 09 23 "610C.-+ &031-/.,-:03

There were widespread j.9.?. strikes throughout [ndia, 3eylon and the Piddle

East with the 9irforce rank and file demanding speedier demobilimation.

f#,,, ~"<!0" , J&"#"/ 0()0$" +&0$),!(2 70! 1%()070$

&'#07-6 (!*8=,6 G0&0!"7($,6 70"0F701#*.-6 (,!, $0)0&-" )&"%07!,

*($0&,)2 #"/0%,!,1;,I.

%2/-:2C ED.:E2C+3-1 ,2.1+4 6? 4:99+/+3- .12H+

Partial equivalents are also caused by diIIerent syntactical usage. The priority

oI Syntax due to the analytical character oI the English language is reIlected in a

number oI Ieatures Iirmly established in it by usage. ChieI among them are: the use

oI homogeneous members which are logically incompatible, a peculiar use oI

parentheses, the morphological expression oI the subject in the principal and the

subordinate clauses, etc.

dithout pomp and circumstance, {.9.T.w. closed its naris headFquarters on

?riday e4ening. The building which has housed the >ecretariat and the @C

delegations for some @ years has been rapidly emptying of furniture and staff.

+'),;* 7""&0/ %"1 7('$0< +-.0(), , ;"&"/0,< 1$&-!(2 .)%F

$7&),& OVpc 7 U&,8". Y#,", 7 $0)0&0/ 7 )""," @ !") &1/"=!,(2

("$&")&,) , #"!":;,, @C :0(*#&()7, %-()&0 0+*()"!0 \ ,1 ":0 7-7"1!,

/"%"!2 , 7-"6!, 7(" (0)&*#,$,.

The meaning oI the verb 'has been emptying of is rendered in Russian by

three verbs in conIormity with the norm and usage oI Russian language valency:

] 1#," 0+*()"!0, /"%"!2 7-7"1!,, (0)&*#,$, 7-"6!,.

A parenthetical phrase or clause sometimes breaks up the logical Ilow oI the

sentence which is common English as the relations between the members oI the

sentence are clear due to the priority oI syntax. But such use necessitates a recasting

oI the Russian sentence, the parenthetical clause must be placed where it logically

belongs to, sometimes even Iorming a separate sentence.

The Xustice narty in Turkey has taken part in a coalition, and on another

occasion its leader has been asked \ but failed \ to form a go4ernment.

U&),' J+&7"#!,70(), 7 p*&;,, 0#, &1 *()707! 7 $0!,;,00/

+&7,)"!2()7", 7 #&*:0< &1 !,#"&* +&),, %-!0 +&"#!08"0 (H0&/,&07)2

+&7,)"!2()70, 0 M)0 "/* " *#!0(2 .

As to the morphological expression oI the subject in the principal and the

subordinate clause it should be noted that syntactical hierarchy requires the use oI a

noun in the Iormer and oI a pronoun in the latter, regardless oI their respective order.

The dark 9lgerian were ripe and as they crawled, the men picked the grapes

and ate them. (J. Steinbeck).

"&-< !8,&($,< 7,0:&# *8" +0(+"!, , +&0#7,:7.,"(' +0!1$0/

(0!#)- (&-7!, :&01#2' , "!, ,6.

The subordinate clause is translated by an attributive participle group to avoid

the use oI a second subject.

(/++ 234 L0.34 =1+ 09 K/2BB2/ (0/B1

Grammatical Iorms are generally used Ireely according to their own meaning

and their use is determined by purely linguistic Iactors, such as rules oI agreement,

syntactic construction, etc. in such cases their use is not Iree but bound. For example,

in English the singular or the plural Iorm oI a noun preceded by a numeral depends

upon the number oI things counted: one table, twenty one tables; in Russian the

agreement depends on the last numeral: 0#, ()0!, #7#;)2 +')2 ()0!07.

The rule oI sequence oI Tenses is another case in point: the use oI the tense in

the English subordinate clause is bound. II the past Tense is used in the principal

clause, the Past or the Future-in-the-Past must be used in the subordinate clause

instead oI the Present or oI the Future, e.g. Qe says that he speaks English \ 0

:070&,), )0 1") :!,<($,<_ he said that he spoke English \ 0 ($1!, )0 0

:070&,) +0F:!,<($,.

This purely Iormal rule oI the sequence oI tenses does not Iind its reIlection in

translation as no such rule exists in Russian and the use oI the tense Iorm in the

dependent clause is Iree and is determined by the situation.

It should be borne in mind that in reported speech in newspaper articles, in

minutes, in reports and records this rule oI the sequence oI tenses is observed

through the text: the sequences are governed by the Past Tense oI the initial sentence

he said, it was reported, they declared, he stressed, etc.

To conclude, only Iree Iorms are rendered in translation and bound Iorms

require special attention.

T?@+1 09 K/2BB2-:,2C T/23190/B2-:031

As has been said, divergences in the structures oI the two languages are so

considerable that in the process oI translation various grammatical and lexical

transIormations indispensable to achieve equivalence. These transIormations may be

classed into Iour types: 1. transpositions; 2. replacements; 3. additions; 4. omissions.

This classiIication, however, should be applied with reservation. In most cases they

are combined with one another, moreover, grammatical and lexical elements in a

sentence are so closely interwoven that one change involves another, e.g.

9s they lea4e dashington, the four foreign ministers will be tra4eling together

by plane.

(" ")-&" /,,()& ,0()&-6 #"! +0!")') ,1 .,:)0 7/"()".

The Iollowing types oI transIormations have been resorted to in the translation

oI this complex sentence:

1. The complex sentence is translated by a simple one (replacement oI sentence

type);

2. The word order is changed (transposition);

3. The subordinate clause oI time is rendered by an adverbial modiIier oI place

(replacement oI member oI the sentence);

4. The meaning oI the predicate and oI the adverbial modiIier is rendered by

the predicate (both lexical and grammatical transIormations replacement and

omission);

5. The meaning oI the deIinite article is rendered lexically (addition).

The above analysis shows that all the Iour types oI transIormations are used

simultaneously and are accompanied by lexical transIormations as well.

T/231@01:-:031

Transposition may be deIined as a change in the order oI linguistic elements:

words, phrases, clauses and sentences. Their order in the TL text may not correspond

to that in the SL text.

This change oI order is necessary to preserve Iully the content oI the utterance

while observing the norms oI the TL.

In considering the universal categories oI deIiniteness and indeIiniteness

mention has been made oI the two main parts oI the sentence Irom the point oI view

oI communication, viz. the known (theme) and new (rheme) elements oI the utterance

and their respective place in English and in Russian sentences. It should also be noted

that the traditional word order in English is Subject Predicate Object Adverbial

modiIiers while the common tendency in Russian is to place adverbial modiIiers at

the beginning oI the sentence to be Iollowed by the predicate and the subject at the

end, e.g.

>trikes broke out in many iritish industries.

&'#" 0)&(!"< +&0/-.!"0(), "!,$0%&,),, 7(+-6*!,

1%()07$,.

Transposition can also be eIIected within a complex sentence. The arrangement

oI clauses in English is oIten governed by syntactical hierarchy, whereas in Russian

precedence is taken by logical considerations, e.g.

Qe started back and fell against the railings, trembling as he looked up.

(W.M.Thackeray).

1:!'*7 7"&6, 0 71#&0:*!, 0)+&'*! ,, 7"(2 #&08, +&,(!0,!(' $

0:&#".

+@C2,+B+3-1

The substitution oI parts oI speech is a common and most important type oI

replacements. Every word Iunctions in the language as a member oI a certain

grammatical clause, that is, as a distinct part oI speech: noun, verb, adjective or

adverb. But the S and T languages do not necessarily have correlated words

belonging to the same grammatical class. In such cases replacements or replacements

additions are necessary, e.g.

an early bedder \ "!07"$, $0)0&-< &0 !08,)(' (+)2_

to cut4ote somebody \ +0!*,)2 %0!2." :0!0(07 7-%0&6, "/ ]

The Times wrote editorially]F +"&"#070< ())2" :1") p</( +,(!]

The adverb is translated by a noun modiIied by an adjective.

A Irequent use oI nominal and phrase predicates with the key notion expressed

by a noun or an adjective oIten results in the replacement oI a noun by a verb.

9 professor of Esseq Eni4ersity was critical of the Do4ernment social security

policy.

U&0H"((0& T(("$($0:0 *,7"&(,)") $&,),$07! +&7,)"!2()7"*I

+0!,),$* (0;,!20:0 0%"(+"",'.

Semantically link verbs are highly diversiIied. Sometimes it is hard to draw a

clear demarcation line between a nominal predicate and a case oI secondary

predication.

The door at the end of the corridor sighed open and sighed shut again.

(G.H.Cox).

57"&2 7 $0;" $0&,#0& "!" (!-.0 0)$&-!(2 , (07 )$8" "!"

(!-.0 1$&-!(2.

Qe took the bellFrope in his hand and ga4e it a brisk tug. (Conan Doyle).

c (67),! .*&0$ 0) 170$ , &"1$0 ":0 #"&*!.

A phrase predicate is replaced by a verbal predicate.

Adjectives derived Irom geographical names are usually replaced by nouns as

such Russian adjectives evidently tend to express some permanent characteristic trait

but not a temporary one, e.g.

3hilean copper \ ,!,<($' /"#' &*# but 3hilean atrocities \ 17"&()7 7

,!,.

Degrees oI comparison also sometimes cause replacements. Such adjectives in

the comparative degree as more, less, higher, lower, shorter, etc. are oIten translated

by other parts oI speech.

Pore letter bombs ha4e been rendered harmless.

a-!0 0%"17&"8"0 "=" "($0!2$0 +,("/ ( %0/%/,.

Qis audience last night may also ha4e been less than enthusiastic about the

nrime Pinister^s attitude towards Do4ernment spending.

J!*.!,, 701/080, %"10 7('$0:0 70()0&: 0)"(!,(2 $ 7"&."/*

7-()*+!",I +&"/2"&F/,,()&, 7 $0)0&0/ 0 7-($1! (70" 0)0."," $

+&7,)"!2()7"-/ &(60#/.

Another linguistic phenomenon which Irequently causes replacements in

translation is the use oI nouns denoting inanimate things, abstract notions, natural

phenomena and parts oI the body as subjects agents oI the action.

Election year opens on in 9merica which is more di4ided and bitter than at

any time in recent history.

M)0/ :0#* %*#*) +&0,(60#,)2 7-%0&- 7 V/"&,$", $0)0&' "=" ,$0:#

" %-! )$0< &1Z"#,"0< , 01!0%!"0<.

As a matter oI Iact the subject in such constructions is purely Iormal. Actually

it expresses adverbial relations oI time, place, cause, etc.

Parts oI the sentence oIten change their syntactical Iunction in translation thus

causing a complete or partial reconstruction oI the sentence by means oI

replacements.

The dhite Qouse correspondents ha4e largely been beaten into submission by

the nresident.

U&"1,#") :&*%-/ 8,/0/ 1()7,! +0#,,)2(' %0!2.,()70

$0&&"(+0#")07 +&, a"!0/ 50/".

+@C2,+B+3-1 09 1+3-+3,+ -?@+1

The usual types oI replacements are the substitution oI a simple sentence by a

complex one and vice versa; oI the principal clause by a subordinate one and vice

versa; the replacement oI subordination by coordination and vice versa; the

replacement oI asyndeton by polysyndeton and vice versa. These kinds oI

replacements are oIten caused by the existence oI various complexes and structures in

the English language, e.g.

[ saw him cross the street and buy a newspaper.

s 7,#"!, $$ +"&"."! *!,;* , $*+,! :1")*.

A simple sentence is replaced by a complex one.

Parsel Daussault, the airplane manufacturer who is said to be the richest man

in ?rance had defrauded the go4ernment of e million in taqes.

R&("!2 5((0, 7!#"!"; 7,()&0,)"!20< $0/+,,, $0)0&-<, $$

:070&'), '7!'")(' (/-/ %0:)-/ "!07"$0/ 70 K&;,,, 0%0$&!

+&7,)"!2()70, " 7-+!),7 e /,!!,007 #0!!&07 !0:07.

Simple sentences containing inIinitive complexes are usually translated by

complex sentences.

A simple sentence with an absolute participle or a nominative absolute

construction is usually rendered by a subordinate or coordinate complex sentence.

dith the fog rolling away and the sun shining out of a sky of icy blue the

tre4ellers started on the leg of their climb. (Trevanian)

G0:# )*/ +0#'!(' , (0!;" 1(,'!0 60!0#0/ :0!*%0/ "%",

!2+,,()- !, +0(!"#,< M)+ (70":0 70(608#",'.

It should also be noted that the type oI the subordinate clause may be changed

on the strength oI usage.

>he glanced at irendon, where he sat on a chair across her. (W.Deeping).

c +0(/0)&"! a&"#0, $0)0&-< (,#"! ()*!" +&0),7 "".

The adverb 'where probably does not Iunction here as an adverb oI place but

rather as a word qualiIying the sitter.

Apart Irom replacing a simple sentence by a subordinated or coordinated

complex sentence it can also be replaced by two, or more simple sentences. It is

especially practiced in the translation oI the so-called 'leads. A lead is the Iirst

sentence oI news-in-brieI which contains the main point oI the inIormation. It usually

coincides with the Iirst paragraph and is usually divided into two or more sentences

in translation.

Thousands of 9lgerians tonight fled from the kdead cityl of wrleanswille after

a twel4eFsecond earthquake had ripped through central 9lgeria, killing an estimated

@,@ people.

1. p-(', 8,)"!"< %"8!, (":0#' 02I ,1 r/"&)70:0 :0&0#t

c&!"7,!', (+('(2 0) 1"/!")&'(",', #!,7.":0(' #7"#;)2 ("$*#.

2. Y"/!")&'("," +&0,10.!0 7 ;")&!2-6 &<06 V!8,&.

3. U0 +&"#7&,)"!2-/ #-/ +0:,%!0 @.@ "!07"$.

On the other hand a complex sentence may by replaced by a simple one.

[t was at the C

th

3ongress that the Dreat jussian writer Paqim Dorky met

genin for the first time.

"!,$,< &*(($,< +,()"!2 R$(,/ L0&2$,< 7+"&7-" 7()&"),!(' (

y",-/ C (Z"1#" +&),,.

Qe could not say anything unless he was prompted. (Taylor Caldwell).

a"1 +0#($1$, 0 " /0: , (!07 ($1)2.

"44:-:031

The tendency towards compression both in the grammatical and the lexical

systems oI the English language oIten makes additions necessary and indispensable.

Much has already been said about additions that accompany transpositions and

replacements. This is particularly true in the translation oI inIinitive, participle and

gerundial complexes. There are other cases when additions are caused by compressed

structures such as the absolute possessive, attributes Iormed by juxtaposition N

1

N

2

structures and by attributive groups.

The model N

1

N

2

oIten requires additions in translation: riot police \

(+";,!2-" 0)&'#- +0!,;,, #!' +0#7!",' *!,-6 %"(+0&'#$07_ death

4ehicle \ 7)0/.,, *%,7.' +&0608":0, bare beaches \ +!'8,, :#" /080

$*+)2(' %"1 $0()I/07.

Sometimes additions are required by pragmatic considerations: pay claim \

)&"%07," +07-.",' 1&%0)0< +!)-, welfare cuts \ *&"1-7,"

%I#8")-6 ((,:07,< (0;,!2-" *8#-_ herring ban \ 1+&"=","

!07,)2 ("!2#2 7 J"7"&0/ /0&" .

Attributive groups are another case in point. The elements Iorming such groups

vary in number, their translation into Russian as a rule requires additions, e.g. oil

thirsty Europe \ 7&0+, ,(+-)-7I=' "67)$* "H),_ XobsFforFyouth 3lub \

$!*%, ()7'=,< (70"< ;"!2I 0%"(+",)2 /0!0#"82 &%0)0<.

9 handful of dates and a cup of coffee habit (J.Galsworthy)

U&,7-$ +,))2(' :0&()0$0< H,,$07 , .$0< $0H".

Attributive groups present great variety because oI the number and character oI

the component elements. The main task Iacing the translator is to establish their

semantic and syntactic relations with the word they modiIy, e.g.

Three {icosia Dreek language newspapers \ p&, :1")- :&""($0/

'1-$", 7-60#'=," 7 O,$01,,.

The decoding oI an attributive group, however, does not always involve

additions, but merely transpositions and replacements, e.g.

9 million pound forged bank draft fraud \ VH"& ( +0##"!2-/ 7"$("!"/

/,!!,0 H*)07 ()"&!,:07.

Additions are also caused by discrepancy in the use oI the plural and singular

Iorms oI certain nouns.

Delegates from 4arious industries \ +&"#()7,)"!, &1!,-6 0)&(!"<

+&0/-.!"0(),.

They Wthe imperialistsN ha4e built up dangerous tensions in the world with an

arms race of unprecedented cost and sime.

f/+"&,!,()- (01#!, 0+(-" 0:, +&'8"0(), 7 /,&", &17"&*7

"%-7!*I , #0&0:0()0'=*I :0$* 700&*8",<.

Additions are not inIrequently caused by lexical reasons. A single instance may

suIIice here as the problem will be considered at length in the Iollowing chapter.

Additions are indispensable in the translation oI verbs which bring Iorth in some

context two semes simultaneously.

]Pr 9mes complained his way out of bed ] and went to the door.

(J.Steinbeck)

R,()"& T</(, $&'6)', 7-!"1 ,1 +0()"!, , +0+!"!(' $ 760#0< #7"&,.

Another cause oI additions is English word building, e.g. conversation and the

use oI some non-equivalent suIIixes.

de showered and dressed.

R- +&,'!, #*. , 0#"!,(2.

The peace campaign snowballed rapidly.

G/+,' 7 1=,)* /,& &0(! ( "7"&0')0< %-()&0)0<.

Qe is a chancer.

c "!07"$, $0)0&-< !I%,) &,($07)2.

OB:11:031

Some lexical or structural elements oI the English sentence may be regarded as

redundant Irom the point oI view oI translation as they are not consonant with the

norms and usage oI the Russian language, e.g.

?or the fishermen of jebun, the notion that young outsiders may choose to

adopt their way of life is both fascinating and perpleqing.

|-%$/ 0()&07 |"%* $8")(' *#,7,)"!2-/ , ()&-/, )0

+&,"18' /0!0#"82 /08") +&"#+0"()2 ,6 0%&1 8,1,.

Two omissions have been made here. The meaning oI the word 'notion is

implied in the predicate oI the Russian sentence and this word can saIely be leIt out.

The verb 'to choose and 'to adopt may be regarded as synonymous and the

meaning oI these two verbs is Iully covered by the Russian verb +&"#+0"()2 which

implies choice.

Some typical cases oI redundancy may be mentioned here: synonymous pairs,

the use oI weights and measures with emphatic intent, subordinate clauses oI time

and place.

Homogeneous synonymous pairs are used in diIIerent styles oI the language.

Their use is traditional and can be explained by extra-linguistic reasons: the second

member oI the pair oI Anglo-Saxon origin was added to make clear the meaning oI

the Iirst member borrowed Irom the French language, e.g. my sire and father. It was

done as O.Jespersen writes in his book 'Growth and Structure oI the English

language '.Ior the beneIit oI those who were reIined expression. Gradually

synonymous pairs have become a purely stylistic device. They are oIten omitted in

translation even in oIIicial documents as pleonastic, e.g.

Equality of treatment in trade and commerce. \ |7-" 701/080(), 7

)0&:07!".

The purposes of the destern nowers in pouring arms into [srael ha4e been

open and unconcealed.

Y+#-" #"&87- ,$0:# " ($&-7!, (70,6 ;"!"<, +0()7!'' 0&*8,"

f1&,!I.

The broadest definition is that the 9rctic is the region of permafrost or

permanently fromen subsoil.

J/0" .,&0$0" 0+&"#"!"," V&$),$, \ M)0 0%!()2 7"0< /"&1!0)-.

Words denoting measures and weights are Irequently used in describing people

or abstract notions. They are either omitted or replaced in translation.

E4ery inch of his face eqpressed amamement. (P.G.Wodehouse).

O ":0 !,;" %-!0 +,(0 ,1*/!",".

Qe eqtracted e4ery ounce of emotion from jachmanino4^s Third 3oncerto.

c +0$1! 7(I M/0;,0!20()2 p&")2":0 $0;"&) |6/,07.

Subordinate clauses oI time and oI place are Irequently Ielt to be redundant in

Russian and are omitted in translation.

The storm was terrific while it lasted.

a*&' %-! *8('.

Sometimes even an attributive clause may be regarded as redundant and should

be omitted in translation.

9nd yet the migrants still pour in from the depressed {ortheast of irasil, many

of them walking the @. miles or more in search og a better life than the one they

left.

f )"/ " /""", +"&"("!";- 7(" "=" +&,%-7I) ,1 &<0 %"#()7,'

J"7"&0F70()0$" a&1,!,,_ /0:," ,1 ,6 +&060#') &(()0'," 7 )-('* /,!2 ,

%0!"" 7 +0,($6 !*."< 8,1,.

The grammatical structure oI any language is as important as its word-stock or

vocabulary. Grammatical meanings are no less signiIicant than lexical meaning as

they express such Iundamental categories as tense relations, gender, number,

modality, categories oI deIiniteness and indeIiniteness, etc. Some oI these categories

may be expressed grammatically in diIIerent ways owing to the existence oI

grammatical synonymy. But sometimes they can also be expressed lexically.

The main translation principle should never be lost sight oI what is expressed

in another, generally by means oI transIormations.

LECTURE

*EM'&"* %OL*EI)

N; *+J:,2C $:99+/+3,+1 L+-O++3 *23H.2H+1

Languages diIIer in their phonological and grammatical systems; their systems

oI meaning are also diIIerent. Any language is able to describe things, notions,

phenomena and Iacts oI liIe. This ability oI language ensures cognition oI the outside

world. But the ways oI expressing these things and notions usually vary in diIIerent

languages. That means that diIIerent languages use diIIerent sets oI semantic

components, that is, elements oI meaning to describe identical extra-linguistic

situations.

>he is not out of school yet. (G.Heyer).

c "=" " $0,! .$0!- W*=" *,)(' 7 .$0!"N.

The same Iact is described in the English and the Russian languages by

diIIerent semantic elements.

ienamin paced his chamber, tension building in him. (E.Taylor).

a"#8/, .:! +0 $0/)", ":0 +&'8"0" (0()0'," 7("

*(,!,7!0(2.

The correlated verbs 'to build and ()&0,)2 (primary meanings) have

diIIerent semantic structures, they are not co-extensive and do not cover each other.

Consequently the verb ()&0,)2 is unacceptable in this context. Equivalence is

achieved by the choice oI another verb *(,!,7)2('. The two verbs 'to build and

*(,!,7)2(' taken by themselves express diIIerent notions, but in this context they

possess the same semantic component viz. the component oI intensiIication (oI

tension). A non-correlated word is oIten selected in translation because it possesses

some common semantic component with the word oI the SL text, as in the present

case (to build \ *(,!,7)2('). The existence oI a common seme in two non-

correlated words is a Iactor oI primary importance in the choice oI equivalents which

opens up great possibilities Ior translators. Another example may illustrate this point.

The cash needed to repair the canal is sitting in the bank.

5"2:,, +&"#1"-" #!' &"/0) $!, 7(" "=" !"8) 7 %$".

The verb 'to sit and !"8)2 are by no means correlated words. But they

possess one seme in common to be at rest, to be unused.

Three Types of Lexical #eaning

As one oI the main tasks oI translation is to render the exact meaning oI words,

it is important to consider here the three types oI lexical meaning which can be

distinguished. They are: referential$ emotive and stylistic.

+9+/+3-:2C meaning (also called nominative, denotative or cognitive) has

direct reIerence to things or phenomena oI objective reality, naming abstract notions

and processes as well. ReIerential meaning may be primary and secondary thus

consisting oI diIIerent lexical Semantic Variants (LSV).

EB0-:E+ meaning unlike reIerential meaning has no direct reIerence to things

or phenomena oI objective reality but to the Ieelings and emotions oI the speaker.

ThereIore emotive meaning bears reIerence to things, phenomena or ideas through

the speaker`s evaluation oI them. Emotive meaning is inherent in a deIinite group oI

words even when they are taken out oI the context.

)-?C:1-:, meaning is based on the stylistic stratiIication oI the English

vocabulary and is Iormed by stylistic reIerence, e.g. face (neutral), countenance

(literary), mug (colloquial).

+9+/+3-:2C I+23:3H 234 :-1 +34+/:3H :3 T/231C2-:03

Lexical transIormation which are practically always required in the rendering

oI reIerential meaning in translation are caused by various Iactors. They may be

classed as Iollows:

a) different vision oI objects and phenomena and different approach to them;

b) different semantic structure oI a word in the SL and in the TL;

c) different valency or collocability;

d) different usage. DiIIerent vision.

It is common knowledge that one and the same object oI reality may be viewed

by diIIerent languages Irom diIIerent aspects: the eye (oI the needle *.$0 ,:0!$,;

hooks and eyes \ $&I$, , +")"!2$,N.

Qot milk with skin on it \ :0&'"" /0!0$0 ( +"$0< .

Desalination \ 0+&"(","_ 4isible to the naked eye \ 7,#,/-<

"700&*8"-/ :!10/_ a fortnight Wforteen nightsN \ #7" "#"!,.

Qe li4es neqt door \ c 8,7") 7 (0("#"/ #0/".

All these words (naked eye \ "700&*8"-< :!1_ fortnight \ #7" "#"!,_

neqt door \ (0("#,< #0/) describe the same Iacts and although Iormally not

correlated they are equivalents.

Qe was no armchair strategist \ c 0)I#2 " %-! $%,")-/

()&)":0/.

Not only words oI Iull meaning but even prepositions may imply diIIerent

vision.

Qe folded his arms across his chest, crossed his knees.

c ($&"(),! &*$, :&*#,, +0!08,! 0:* 0:*.

This Iactor (diIIerent vision) usually presents little diIIiculty Ior the translator

but it must never be overlooked, otherwise the translator may lapse into literal

translation. The diIIiculty arises when such words are used Iiguratively as part oI

some lexical stylistic device, that is, when they IulIill a stylistic Iunction, e.g.

[nstant history, like instant coffee, can be remarkably palatable, at least it is in

this memoir by a former dhitehouse side who sees g.i.X. as kan eqtraordinary gifted

nresident who was the wrong man, from the wrong place, at the wrong time, under

the wrong circumstances.

J07&"/"' ,()0&,', )$ 8" $$ , )$0< (07&"/"-< +&0#*$) $$

&()70&,/-< $0H", ,0:# %-7") *#,7,)"!20 +&,'), +0 $&<"< /"&" M)0

)$ 7 &";"1,&*"/-6 /"/*&6 %-7.":0 +0/0=,$ +&"1,#") 580(0,

$0)0&-< 6&$)"&,1*") ":0 $$ r,($!I,)"!20 (+0(0%0:0 +&"1,#"),

$0)0&-< %-! "+0#60#'=,/ "!07"$0/, &0#0/ ,1 "+0#60#'=":0 /"(), 7

"+0#60#'="" 7&"/', +&, "+0#60#'=,6 0%()0')"!2()76t.

One and the same product is named in the S and T languages according to its

diIIerent properties: the English language stresses the speed with such coIIee can be

prepared whereas the Russian language lays special accent on the Iact that it is

soluble.

A word in one Language may denote, due to diIIerent vision, a wider non-

diIIerentiated notion, while the same notion is, as it were dismembered in the other

language, and, consequently, there are two or more words denoting it. For example,

the Russian word (- corresponds to two English words; 'watch and 'clock. The

Russian word :0&0# has two couterparts; 'town and 'city. And vice versa, one

English word may correspond to two or more Russian words, e.g. 'moon !*,

/"(';, 'bell $0!0$0!, $0!0$0!2,$, %*%",$, 1700$, ($!'$, &-#. The

Russian language uses one word +!"; which is indiscriminately applies 'to terminal

members oI the hand and Ioot, while the English language discriminates between

these members and has accordingly three diIIerent words: thumb, finger, toe.

$:E+/H+3,+1 :3 -5+ )+B23-:, )-/.,-./+ 09 F0/41

The semantic structure oI words presents a complicated problem as the so-

called correlated words oI the T languages are Iar Irom being identical in this respect.

The only exception are some groups oI monosemantic words which will be dealt with

later.

Divergences in the semantic structure oI words oI the S and T languages are

one oI the primary cases oI lexical transIormations. These divergences or

dissimilitudes are connected with certain peculiar Ieatures oI a word or a group oI

words. Even words which seem to have the same meaning in the two languages are

not semantically identical. The primary meanings oI correlated words oIten coincide

while their derivative meanings do not. Thus there is only partial correspondence in

the structures oI polysemantic words as their lexical semantic variants do not cover

one another. Semantic correlation is not to be interpreted as semantic identity and

one-to-one correspondence between the semantic structures oI correlated

polysemantic words in the two languages is hardly ever possible.

Such partial correspondence may be illustrated by the Iollowing analysis oI the

correlated words ()0! and table. Their primary meanings denoting the same article

oI Iurniture are identical. But their secondary meanings diverge. Other lexical

semantic variants oI the word table are: part oI the machine-tool; slab oI wood

(stone); matter written on this; level area, plateau; palm oI hand, indicating character

oI Iortune, etc. Lexical semantic variants oI the word ()0! are: , m, (

, ); x, x (t

, x) etc.

Not inIrequently the primary meaning (and sometimes the derivative meanings

as well) oI an English word consist oI more than one semantic component or some,

Iorming the so-called 'bundles oI semantic elements. This is usually reIlected in

dictionaries which give more than one Russian equivalent oI each LS oI the English

word.

The analysis oI the polysemantic word 'mellow shows that it can modiIy a

wide variety oI objects and notions: Iruit, wine, soil, voice, man, etc. Each sphere oI

its application corresponds to a diIIerent derivative meaning and each meaning

(consisting oI several semes) accordingly has two or more Russian equivalents.

1. t, x, t ( x); 2. txt, t ( );

3. xt ; 4. m, xmx ( );

5. x, t, ( x); 6. txt, t (

); 7. . t, tm. (FAPC)

It also Iollows Irom the above example that there is no single Russian word

with a similar semantic structure corresponding to the word 'mellow and comprising

all its meanings.

$:99+/+3- >2C+3,?

The aptness oI a word to appear in various combinations is described as its

lexical valency or collocability which amounts to semantic agreement. Collocability

implies the ability oI a lexical unit to combine with other lexical units, with other

words or lexical groups. A word as a lexical unit has both paradigmatic and

syntagmatic collocability. The lexical meaning oI a word is revealed in either case.

The contexts in which a word is used bring out its distribution and potential

collocability , thus the range oI lexical valency oI words is linguistically determined

by the lexical meaning oI words, by the compatibility oI notions expressed by them

and by the inner structure oI he language word-stock.

It should be noted that valency comprises all levels oI language its

phonological, syntactical and lexical levels. Only lexical valency will be considered

here.

A detailed analysis oI Iactual material shows that valency in the English

language is broader and more Ilexible than that in the Russian language. This Iact

conIronts the translator with additional diIIiculties, as it enables a writer to use

unexpected individual combinations. It Iollows that valency may be obligatory non-

obligatory and words accordingly Iall into two categories: 'open or discrete words

and 'closed or non-discrete ones. The adjective 'aquiline is a classical example oI

a word with a closed valency (. the Russian adjective $&0/".-<).

Every language has its established valency norms, its types oI word

combinations, groups oI words able to Iorm such combinations. This especially

concerns traditional, obligatory combinations while individual combinations give

greater scope to translators. Individual collocability is by no means arbitrary and must

not violate the existing models oI valency. As a writer may bring out a potential

meaning oI some word he is also able to produce unexpected combinations. Such

individual but linguistically justiIiable collocations belong to the writer`s individual

style in the way as his epithets or metaphors and may be regarded as an eIIective

stylistic device, e.g.

>he had seen many people die, but until now, she had ne4er known a young

foreign death. (R.Godden).

z "" :!16 */,&!0 /0:0 !I#"<, 0 #0 (,6 +0& "< " +&,60#,!0(2

7,#")2 $$ */,&! *8"1"/";, # "=" )$0< I-<.

Words traditionally collocated tend to constitute cliches, e.g. a bad mistake,

high hopes, hea4y sea Wrain, snow), etc. the translator is to Iind similar TL cliches,

traditional collocations: :&*%' 0.,%$, %0!2.," #"8#-, %*&0" /0&", (,!2-<

#08#2 W(":N. The key word in such collocations is a noun, both semantically and

structurally, while the modiIying adjective plays a subordinate role. The key word is

always preserved in translation but the collocated adjective is rendered by a word

possessing a diIIerent reIerential meaning which expresses the same category (in this

case intensity) and corresponds to the TL valency norms. For example:

a bad mistake \ :&*%' 0.,%$

a bad headache \ (,!2' :0!07' %0!2

a bed debt \ "7017&="-< #0!:

a bad accident \ )'8"!-< "(()-< (!*<

a bad wound \ )'8"!' &

a bad egg \ )*6!0" '<;0

a bad apple \ :,!0" '%!0$0.

It should be noted that words playing a qualiIying role may be not only

adjectives but also verbs and adverbs, e.g. trains run \ +0"1# 60#')_ to sit in dry

dock \ ()0')2 7 (*60/ #0$".

The problem oI semantic agreement inevitably arises in the translation oI

phraseological units consisting oI a verb oI wide meaning and a noun (collocations or

set expressions). The verb is practically desemantised and the noun is the semantic

centre oI the collocation.

The translation oI the verb is determined by the law oI semantic agreement,

e.g. to make tea WcoffeeN \ 17&,7)2 < W$0H"N

To make beds \ ()"!,)2 +0()"!,

To make faces \ ()&0,)2 &08,

To make apologies F +&,0(,)2 ,17,",'.

Every language possesses regular and compatible collocations.

9fter a day of hea4y selling and in spite of persistent iank of England support,

the pound closed on Ponday at a new record low against the Enited >tates dollar.

U0(!" )0:0 $$ 7 )""," 7(":0 #' *(,!"0 (%-7!,(2 H*)-

()"&!,:07 , "(/0)&' *+0&*I +0##"&8$* V:!,<($0:0 %$, $ 1$&-),I

%,&8, 7 +0"#"!2,$ $*&( H*) #0(),: &"$0�F,1$0:0 *&07' +0

0)0.",I $ #0!!&*.

The richer the semantic volume oI a word is, the richer is its collocability

which opens up wide translation possibilities.

A detailed analysis oI various collocations shows that individual and

unexpected collocations in diIIerent Iunctional styles are much more Irequent in

English than in Russian.

DiIIerent collocability oIten calls Ior lexical and grammatical transIormation,

though oI the collocation may have its equivalent in Russian, e.g. a kcontro4ersial

questionl \ t but the collocation kthe most contro4ersial nrime

Pinisterl cannot be translated as t t -.

iritain will tomorrow be welcoming on an official 4isit one of the most

contro4ersial and youngest nrime Pinister in Europe.

Y7)& 7 V:!,I +&,%-7") ( 0H,;,!2-/ 7,1,)0/ 0#, ,1 (/-6

/0!0#-6 +&"/2"&F/,,()&07 7&0+-, $0)0&-< 7-1-7") (/-"

+&0),70&",7-" /",'.

>wedens neutral faith ought not to be in doubt.

"&0()2 x7";,, "<)&!,)")* " +0#!"8,) (0/",I.

A relatively Iree valency in the English language accounts Ior the Iree use oI

the so-called transIerred epithet in which logical and syntactical modiIications do not

coincide.

[ sat down to a 4ery meditati4e breakfast.

&1#*/2" ' +&,'!(' 17)&$)2.

Logically the adjective 'meditative reIers to the subject oI the sentence

whereas syntactically it is attached to the prepositional object. This unusual

attachment converts it into a transIerred epithet. The collocation 1#*/,7-<

17)&$ is hardly possible in Russian.

$:99+/+3- =12H+

Traditional usage oI words oI word combinations is typical oI each language.

Traditional S.L. and T.L. usage or cliches do not coincide. The words Iorming such

cliches oIten have diIIerent meanings in the two language but they are traditionally

used to describe similar situations. The problem oI the proper selection oI equivalent

words and cliches can be solved only iI the peculiarities oI the correlated languages

are taken into consideration, e.g.

Qe is sur4i4ed by his wife, a son and a daughter.

c 0()7,! +0(!" ("%' 8"*, (- , #02. WU0(!" ":0 0()!,(2 8",

(- , #02.N

>he ne4er drank boiled water.

c ,$0:# " +,! (-&0< 70#-.

Sometimes diIIerent usage in partly due to diIIerent vision:

The city is built on terrace rising from the lake.

L0&0# +0()&0" )"&&(6, (+*($I=,6(' $ 01"&*.

As a matter oI Iact there two verbs (to rise and (+*($)2(') may be called

conversives, that is, they describe the same situation Irom diametrically opposite

angles.

Sometimes diIIerent usage is apparent in the use oI semantically complete

prepositions.

Qe wrote under se4eral pseudonyms, many of his essays appearing o4er the

name of kgittle {elll. (F.Johnson).

c +,(! +0# &1-/, +("7#0,//,, /0:," ":0 0"&$, +0'7!'!,(2 +0#

+0#+,(2I rG&0.$ O"!!t

Usage is particularly conspicuous in set expressions.

The {ew ealand earthquake was followed by tremors lasting an hour. {o loss

of life was reported.

U0(!" 1"/!")&'(",' 7 O070< Y"!#,, 7 )""," ( 0=*=!,(2

)0!$,. v"&)7 " %-!0 .

The fact that the E> Do4ernment was finally and firmly coming to grips with

crime impressed many.

O /0:,6 +&0,17"!0 7+")!"," )0, )0 +&7,)"!2()70 J0"#,"-6

x))07, $0";, 0"2 M"&:,0 !0 %0&2%* ( +&"()*+0()2I.

Usage plays an important part in translating orders and instructions.

3ommit no nuisance \ 0()7!,7)2(' 70(+&"=")('.

Usage is closely linked with the history and development oI the language, oI its

lexical system. Hence every language creates peculiar cliches, ready-made Iormulae.

They are never violated by the introduction oI additional words or by the substitution

oI their components.

T/231C2-:03 09 I0301+B23-:, F0/41

Monosemantic words are comparatively Iew in number and the bulk oI English

words are polysemantic. English monosemantic words usually have Iull equivalents

in Russian. There are the Iollowing lexical groups oI monosemantic words: 1. proper

names, 2. geographical names, 3. names oI the months and the days oI the week, 4.

numerals, 5. some scientiIic and technological terms, 6. names oI the streets, 7.

names oI hotels, 8. names oI sports and games, 9. names oI periodicals, 10. names oI

institutions and organizations.

The group oI monosemantic words presents considerable variety because oI its

heterogeneous character.

+34+/:3H 09 %/0@+/ #2B+1 :3 T/231C2-:03

The Iunction oI proper name is purely nominative. They help to distinguish a

person, a pet or a place, to recognize them as unique. Thus they have only nominal

meaning and are designated by a capital letter.

There are two ways oI rendering proper names in translation: transcription and

translation.

Transcription is now universally accepted: Mary \ RM&,. Phonetic

peculiarities, however, sometimes interIere and modiIy this principle by causing

certain departures, e.g. the name oI the well-known novelist Iris Murdoch is rendered

with the inserted letter (and sound) 'p A M+.

Translation or representing a SL word by means oI the more or less

corresponding corresponding TL characters, that is, in a graphic way, is no longer

regarded as an acceptable method oI rendering proper names in translation. But

tradition has preserved it in some cases and thereIore this method still survives, e.g.

gincoln is rendered as y,$0!2 and dellington as "!!,:)0. w^Qenry \

c^L"&,.

Traditionally, names oI prominent people are rendered by their Russian

counterparts: [saak {ewton \ f($ O2I)0, 9braham gincoln \ V7&/

y,$0!2, bing Xames \ G0&0!2 s$07. All these Iactors explain the existence oI

double Iorms oI proper names.

A problem by itselI is presented by the translation oI the so-called token names

which reveal some typical Ieatures oI the character named. Sometimes attempts are

made to translate them, in this way Iollowing the writer`s intent, e.g. QumptyF

Dumpty \ x!)< a0!)<, p'+$,Fy'+$, \ >lapFDash, etc. unIortunately this

tendency inevitably conIlicts with the principle oI preserving the national character oI